ABSTRACT

Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy has achieved great success in the clinic; however, only a small fraction of cancer patient benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy, and overcoming resistance to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade has thus become a primary priority. In this study, we demonstrated that administration of PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies resulted in the activation of the complement system and massive generation of C5a. Generation of C5a did not change the accumulation of MDSCs in either the tumor or spleen but enhanced their inhibitory potential. In addition, blockade of C5a-C5aR signaling in combination with PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies greatly enhanced the anti-tumor efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies. Overall, these data indicate an immunosuppressive role of C5a in the context of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy and provide a strong incentive to clinically explore combination therapies using a C5a antagonist.

KEYWORDS: tumor immunotherapy, immune checkpoint blockade, complement C5a, MDSCs, PD-1 treatment resistance

Abbreviations

- C5aR

C5a receptor

- FAC

Flow cytometry

- IHC

Immunological histological chemistry

- MDSC

Myeloid derived suppressor cells

- PD-1

Programmed cell death 1

- PD-L1

Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1

Introduction

Despite promising progress in checkpoint blockade in the clinic, more than half of all cancer patients fail to respond to PD-1 signaling blockade,1 which may be due to immunoregulatory network complexity and tumor and host heterogeneity.2 Therefore, exploration of potential mechanisms restricting the therapeutic efficiency of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade is urgently needed.

The biologic activity of antibodies is attributable to 2 domains that function individually. In antibody-based therapies, recognition of cell-surface antigens by the Fab domain serves as an agonist or antagonist of intracellular signaling, whereas the Fc domain can trigger a proinflammatory response by initiation of the complement system and activation of innate immune effector cells via the Fcγ receptor.3 The therapeutic effect of an anti-CD-20 antibody is abolished in C1q-deficient mice, indicating a fundamental role of complement activation induced by the Fc domain.4 Similarly, complement activation may inevitably occur in checkpoint antibody-based cancer therapies within the tumor microenvironment, which may affect therapeutic efficiency by shifting the immune milieu.

The product of complement activation, C5a, also known as anaphylatoxin, is closely involved in tumor progression,5-7 as various components of the tumor microenvironment express C5aR.8,9 Notably, C5a functions as a chemokine and a boosting factor in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs),10 important immunosuppressive cells that restrain T-cell proliferation and function.11 Furthermore, C5a is angiogenic12 and may directly influence CD8+ T-cell function in an autocrine manner by inhibiting IL-10 production.13 Given the biologic characteristics of the antibody Fc domain and the function of the complement fragment C5a in tumor progression, complement activation induced by anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies might restrict the therapeutic activity of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Thus, exploring the changes in components such as MDSCs within the tumor microenvironment induced by antibody-mediated complement activation may provide novel insights on the factors restricting the therapeutic activity of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade.

In the present study, we demonstrated in murine models that complement activated by anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies restricts tumor regression in a C5a-dependent manner. A considerable amount of C5a was generated within tumor tissue after the administration of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies. We also demonstrated superior therapeutic efficiency of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade against tumors in both C5aR−/− mice and when administered in combination with a C5aR antagonist. We observed an increased T-cell ratio and function in the tumor tissue of mice treated with combination therapy, which may be attributable to a decrease in the immunosuppressive ability of MDSCs under a C5aR antagonist. These results highlight novel restrictive factors for the therapeutic activity of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade and draw attention to complement activation in antibody-based therapies.

Results and discussion

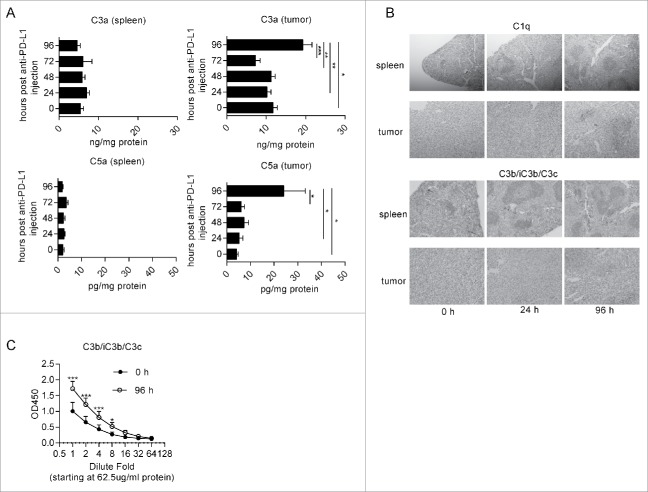

PD-L1 antibody therapy leads to complement system activation

To determine whether the complement system was activated after the administration of anti-PD-L1 antibodies, we intraperitoneally injected anti-PD-L1 antibodies into MC38 tumor-bearing mice. The tumors and spleens were removed at the indicated time points. C3a and C5a levels in homogenates were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Interestingly, we observed that both C3a and C5a were markedly elevated in tumors at 96-hour post antibody injection, while no obvious change was observed in the spleen (Fig. 1A). These results indicated that complement activation by administration of anti-PD-L1 antibodies primarily occurred locally within the tumor rather than systemically. These data are consistent with high expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in the tumor microenvironment (Fig. S1A-B),14,15 which cause massive accumulation of antibodies in tumors.16 Activation of the complement system in tumors is thought to be dependent on the classic pathway because tumor growth inhibition is observed in mice deficient in C4 but not factor B.10 Consistent with the observation, immunohistochemistry staining indicated that the deposition of both C1q and C3b/iC3b/C3c, the cleaved product of C3, was obviously increased on 96-hour post anti-PD-L1 antibody injection in tumors. However, the deposition of C1q and C3b/iC3b/C3c did not increase in the spleen (Fig. 1B). Increased deposition of C3b/iC3b/C3c at 96-hour post antibody administration was also validated by ELISA (Fig. 1C). To determine whether increased C5a enhances the accumulation of MDSCs, we measured the percentage of MDSCs in leukocytes by flow cytometry. However, we detected comparable MDSCs at different time points after the injection of anti-PD-L1 antibodies (Fig. S2 A-C) both in spleens and tumors. These data suggest that anti-PD-L1 antibody injection activated the complement system and induced the generation of C5a, a crucial immune modulator in cancer immunotherapy.

Figure 1.

Anti-PD-L1 treatment leads to activation of the complement system. MC38 tumor-bearing mice (∼100 mm3) were intraperitoneally injected with anti-PD-L1 antibodies. The tumors were removed at the indicated time points (n = 5–6 mice/group). (A) C3a and C5a levels in homogenates from tumors and spleens were quantified by ELISA. (B) C1q and C3b/iC3b/C3c staining of tumors and spleens were quantified by IHC. (C) C3b/iC3b/C3c levels of homogenates from tumors and spleens were quantified by ELISA. One-way ANOVA (A) and Multiple t-test (C) were used to evaluate statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

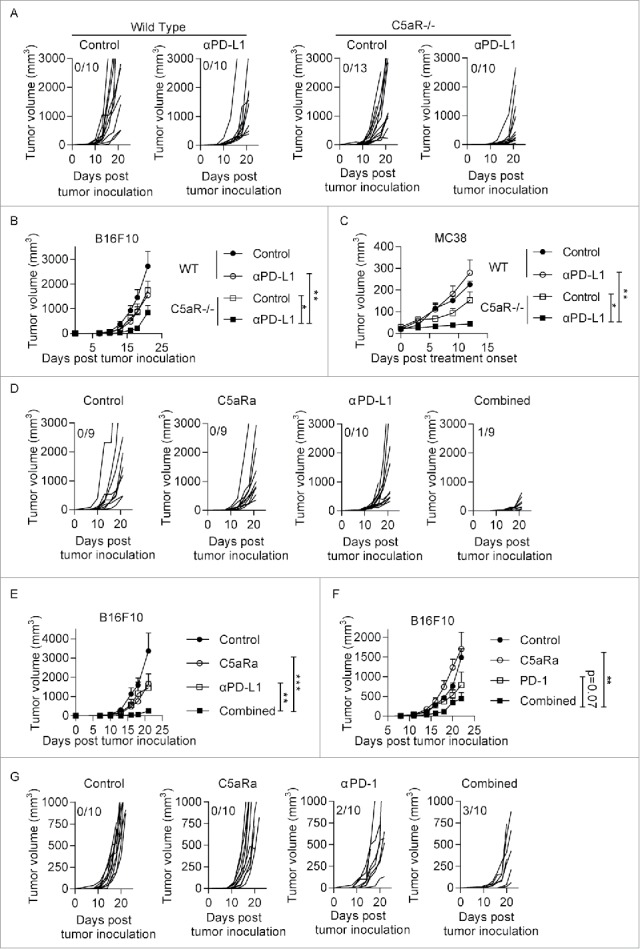

Blocking C5aR signaling promotes the anti-tumor efficacy of checkpoint blockade

As the injection of PD-L1 antibodies induces the massive production of C5a, we hypothesized that blocking C5a-C5aR signaling would enhance PD-L1 antibody efficacy by modulating the tumor microenvironment (i.e., MDSC components). To test this hypothesis, B16F10 cells were subcutaneously inoculated into wild-type (WT) or C5aR−/− mice. Four days later, the mice were treated with PD-L1 antibodies or corresponding isotype control antibodies respectively. Interestingly, tumor control efficacy was greatest in the C5aR−/− mice treated with PD-L1 antibodies (Fig. 2A-B). A similar result was observed in a MC38 tumor model (Fig. 2C). We also used PMX53 (a C5aR antagonist) to pharmacologically block C5aR signaling and observed that PMX53 greatly enhanced the efficacy of PD-L1 antibodies (Fig. 2D-E) and anti-PD-1 antibodies (Fig. 2F-G) in a B16F10 tumor model. These data suggest that blocking C5a-C5aR signaling may maximize the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies.

Figure 2.

Blocking C5aR signaling promotes the anti-tumor efficacy of checkpoint blockade. (A-B) Tumor cells (3 × 104 B16F10 cells in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline) were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of WT or C5aR−/− mice on day 0. The mice were treated with anti-PD-L1 antibodies or the corresponding isotype control on days 4, 7, 10 and 13. Tumor growth was monitored every 2–3 d (n = 10–13 mice/group). (C) Tumor cells (5 × 105 MC38 cells in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline) were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of WT or C5aR−/− mice on day 0. The mice were treated with anti-PD-L1 antibodies or the corresponding isotype control on days 7, 10 and 13. Tumor growth was monitored every 2–3 d (n = 5–6 mice/group). (D-E) Tumor cells (3 × 104 B16F10 cells in 100 μl phosphate-buffered saline) were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of WT mice on day 0. For pharmacological blockade of C5aR signaling, the C5aR antagonist (C5aRa) (PMX53, GL Biochem; 1 mg/kg daily) was subcutaneously injected into C57BL/6 mice on days 4 to 14. PD-L1 antibodies or the corresponding isotype control were injected on days 4, 7, 10 and 13. Tumor growth was monitored every 2–3 d (n = 9–10 mice/group). (F-G) Tumor cells (3 × 104 B16F10 cells in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline) were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of WT mice on day 0. For pharmacological blockade of C5aR signaling, the C5aR antagonist (C5aRa) (PMX53, GL Biochem; 1 mg/kg daily) was subcutaneously injected into C57BL/6 mice on days 4 to 14. PD-1 antibodies or the corresponding isotype control were injected on days 4, 7, 10 and 13. Tumor growth was monitored every 2–3 d (n = 10 mice/group). Two-way ANOVA (B, C, E, G) was used to evaluate statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

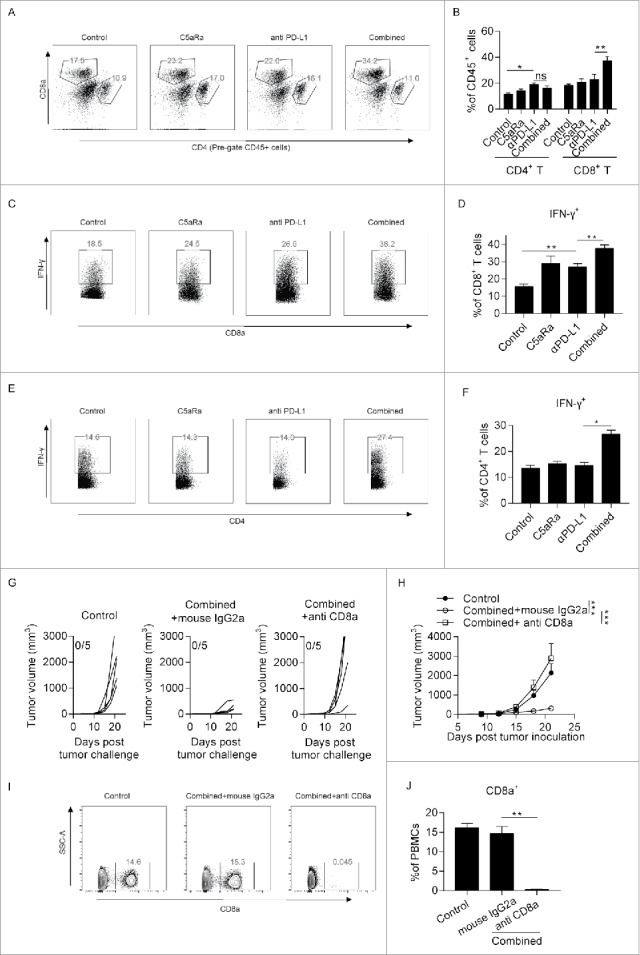

Anti-tumor effect of combined C5aR signaling blockade and PD-L1 antibody is CD8+ T cell-dependent

We further evaluated whether adding a C5aR antagonist to anti-PD-L1 treatment increased the accumulation and activation of anti-tumor T lymphocytes. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that combined treatment with the C5aR antagonist and anti-PD-1 antibodies augmented the percentages of infiltration of CD8+ T cells but not CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3A-B). Furthermore, we found that the percentages of IFN-γ+ cells were significantly increased in both CD4+ T (Fig. 3C-D) cells and CD8+ T (Fig. 3E-F) cell populations in combined group. These data suggest that co-administration of C5aRa and PD-L1 antibodies promotes the accumulation and activation of T cells in tumor microenvironment, which may contribute to its anti-tumor effect of combined therapy. To validate whether CD8+ T is responsible for anti-tumor effect of combined therapy, we depleted CD8+ T cells by injecting anti-CD8 antibodies in B16F10 implanted tumor model. The depletion efficacy was validated by flow cytometry (Fig. 3I-J). Our data suggest that CD8+ T cell depletion abrogated tumor controlling effect of combined therapy (Fig. 3G-H), suggesting that CD8+ T cells plays a key role in controlling tumor growth in combined therapy group.

Figure 3.

Anti-tumor effect of combined C5aRa and PD-L1 antibody is CD8+ (T)cell-dependent. (A-E) Tumor cells (5 × 105 MC38 cells in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline) were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of WT mice on day 0. The mice were treated with anti-PD-L1 antibodies or the corresponding isotype control on days 7, 10 and 13. For pharmacological blockade of C5aR signaling, the C5aR antagonist (C5aRa) (PMX53, GL Biochem; 1 mg/kg daily) was subcutaneously injected into C57BL/6 mice on days 4 to 14. The tumors and spleens were removed on day 16 post tumor challenge, and single cells were examined by flow cytometry (n = 5 mice/group). (A-B) Percentages of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cell and CD4+ T cells in CD45+ cells. (C-D) Percentages of IFN-γ+ cells in CD8+ T. (E-F) Percentages of IFN-γ+ cells in CD4+ T. (G-H) Mice were treated as described in Fig. 2D-E. For depletion of CD8+ T cell, 200ug anti-mouse CD8 antibodies were given on day 5 and 9 post tumor inoculation. Tumor growth was monitored every 2–3 d (n = 5 mice/group). (I-J) Blood cells were collected from mice on day 12 post tumor inoculation. Percentages of CD8a+ T in PBMCs were determined by flow cytometry. Student t-test (B, D, F, J) or 2-way ANOVA (H) was used to evaluate statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

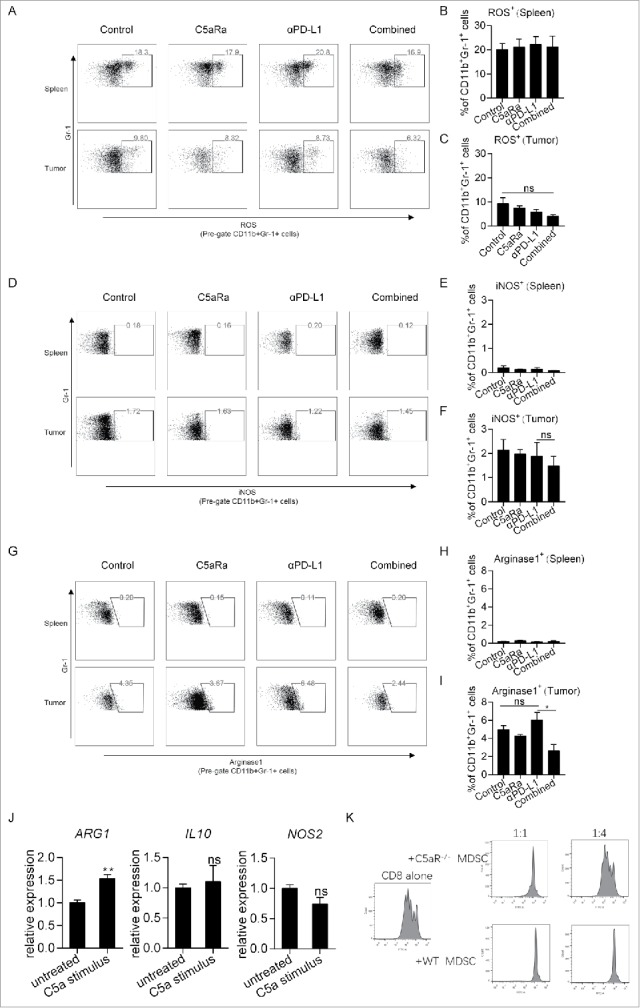

C5aR signaling is involved in controlling of suppressive potential of MDSCs

Previous studies reported that myeloid cells, including dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages and MDSCs, highly express C5aR,17,18 suggesting that these cells are likely affected by C5a. To this end, we determined the myeloid components in both tumors and spleen. C5aR signaling was reported to be essential for the accumulation of MDSCs in a mouse transplanted TC-1 tumor model,10 but unexpectedly, we observed comparable percentages of DCs, tumor-associated macrophages and MDSCs in both tumors and spleens (Fig. S3 A-F). Our data are consistent with previous studies12,13 that have shown no change in the percentage of MDSCs after blocking C5aR signaling. These results suggest that the chemotactic effect of C5a on MDSCs might be tumor type specific. In addition, as C5a has been suggested to promote the inhibitory effects of MDSCs, we also determined whether C5a, generated by PD-L1 antibody treatment, promoted MDSC to express key inhibitory effectors including ROS (Fig. 4A-C), iNOS (Fig. 4D-F) and arginase (Fig. 4G-I).19,20 We found that splenic MDSCs expressed more ROS than tumor MDSCs, while tumor MDSCs showed an increased expression of arginase and iNOS, which are consistent with previous report.21 Interestingly, we found a decrease of arginase in tumor MDSCs in combined therapy group when compared with tumors from mice received PD-L1 antibodies only (Fig. 4G-I). To further validate if C5a influence MDSCs function directly, we stimulate the splenic MDSCs, isolated from tumor bearing mice, with mouse recombinant C5a and examined the expression of ARG1, NOS2 and IL-10 by qPCR. Our data suggest that the addition of C5a stimulated the expression of ARG1 (∼1.5-fold) in isolated splenic MDSCs but did not affect the expression of NOS2 and IL-10 (Fig. 4J). Furthermore, we found that MDSCs from C5aR−/− tumors are less suppressive than their WT counterparts (Fig. 4K), which was consistent with the former study.10 Our data suggest that C5a, generated by PD-L1 antibodies treatment, is involved in controlling the suppressive potential of MDSCs. Mechanically, C5a exerts its function by binding to its specific receptor C5aR, which is expressed mainly by myeloid cells, via activation of PI3K signaling.6,22 Furthermore, both p110δ and p110γ isoforms of PI3K have been implicated in immunosuppression mediated by myeloid cells in solid tumors and use of IPI-145, a selective p110δ/γ inhibitor abrogated local immunosuppression mediated by MDSCs.23,24 Therefore, we believe that complement activation may alter MDSCs function via influencing PI3K signaling.

Figure 4.

C5aR signaling is involved in controlling of suppressive potential of MDSCs. Mice were treated as described in Fig. 3A-E. Suppressive potential of MDSCs from tumors and spleens were determine by flow cytometry (n = 5 mice/group). (A-C) Percentages of ROS+ cell in MDSCs. (D-F) Percentages of iNOS+ cell in MDSCs. (G-I) Percentages of arginase1+ cell in MDSCs. (J) Splenic MDSCs were isolated from MC38 tumor-bearing mice and stimulated with/without recombinant mouse C5a, followed by examination of the mRNA expression of ARG1, IL-10 and NOS2. (K) Tumoral MDSCs were isolated from WT/C5aR−/− MC38 tumor-bearing mice, and a T-cell proliferation inhibition assay was performed as described in the Methods. At 72 h post stimulation, the T cells were collected and examined by flow cytometry. Student t-test (B, C, E, F, H, I, J) was used to evaluate statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Concluding remarks

Blocking PD-1/PD-L1 signaling has recently been widely used in the treatment of various cancers, including metastatic melanoma,25 renal cell carcinoma26 and metastatic non-small cell lung cancer.27 However, the response rate remains low.28 Thus, there is a critical need to determine the resistant mechanisms of checkpoint blockade. The results of the present study suggest that checkpoint blockade treatment leads to activation of the complement system and massive generation of C5a, which augments the suppressive activity of MDSCs to inhibit the efficacy of checkpoint blockade therapy. Thus, the combination of inhibition of C5a/C5aR signaling with checkpoint blockade might provide a novel strategy to overcome resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy.

Materials and methods

Mice

Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). C5aR−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) were obtained from Dr. Craig Gerard (Harvard Medical School). The mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions and housed and treated in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Third Military Medical University.

Cell lines and cell culture

B16F10 cells (mouse melanoma cell line) and MC38 cells (mouse colon cancer cell line) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All cell lines were examined and authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling in September 2015. All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco) plus penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 U/ml) at 37°C in an incubator with 5% CO2.

Tumor challenge and treatment experiments

Tumor cells (3 × 104 B16F10 or 5 × 105 MC38 in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline) were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of mice on day 0. For PD-L1 blockade, anti- anti-PD-L1 mAb (200 μg; clone 10F.9G2; Bioxcell) or control rat IgG2b (200 μg; clone LTF-2; Bioxcell) was intraperitoneally injected on days 4, 7, 10 and 13 post tumor challenge for the B16F10 model or on days 7, 10 and 13 post tumor challenge for the MC38 model. The C5aR antagonist (PMX53, GL Biochem) or its control AcF(OP(D)ChaA(D)R) (GL Biochem) was dissolved in 100% ethanol, and then stock at 1mg/ml in PBS containing 5% ethanol. For pharmacological blockade of C5aR signaling, PMX53 (1 mg/kg daily) or AcF(OP(D)ChaA(D)R) (GL Biochem) was subcutaneously injected into C57BL/6 mice on days 4 to 14. For PD-1 blockade, the mice were treated with anti-PD-1 mAb (250 μg; clone RMP1–14; Bioxcell) or control rat IgG2a (250 μg; clone 2A3; Bioxcell) on days 4, 7, 10, 13 post tumor inoculation. The tumor area was measured using an electronic caliper, every 2–3 d in 2 dimensions (length and width).

ELISA

MC38 tumor-bearing mice (∼100 mm3) were injected with anti-mouse PD-L1 antibodies (200 μg; clone 10F.9G2; Bioxcell), and the tumors and spleens were subsequently removed at the indicated time points. The tumors were homogenized in pre-cold PBS containing FUT-175(BD) to prevent ex-vivo activation of complement. For the measurement of C3b/iC3b/C3c, the plates were coated with purified Rat Anti-Mouse C3b/iC3b/C3c (clone 2/11, Hycult Biotech, 4 μg/ml, pH 9.6) at 4 °C overnight and subsequently blocked with ELISA Diluent (Biolegend) for blocking for 2 hours at room temperature, followed by incubation with the samples. The samples' protein concentrations were normalized to 62.5 μg/ml as the starting concentrations. Then, a HRP-conjugated mouse anti-mouse C3 (clone B-9, Santa Cruz, 2 μg/ml) was used as a secondary antibody as it was reported before.29 For the measurement of C3a, the plates were coated with purified Rat Anti-Mouse C3a (clone I87–1162, BD, 4 μg/ml, pH 6.6) overnight and subsequently blocked with ELISA Diluent (Biolegend) for 2 h, followed by incubation with the samples. Biotinylated Rat Anti-Mouse C3a (clone I87–419, BD, 2 μg/ml) was used for detection, and purified recombinant mouse C3a (BD) was used as a standard. To measure C5a, the plates were coated with purified Rat Anti-Mouse C5a (clone I52–1486, BD, 4 μg/ml, pH 9.6) overnight and subsequently blocked with ELISA Diluent (Biolegend) for blocking for 2 h, followed by incubation with the samples. Biotinylated Rat Anti-Mouse C5a (clone I52–278, BD, 2 μg/ml) was used for detection, and purified recombinant mouse C5a (BD) was used as a standard.

Flow cytometry

To obtain single-cell suspensions, MC38 tumors were harvested on day 16 post tumor inoculation and digested with 1 mg/ml collagenase I (Gibco) and 1 mg/ml Dispase II (Roche) for 45 min at 37°C. The cells were subsequently blocked with anti-FcR (clone 93; Biolegend) and stained with antibodies against CD11b (clone M1/70; Biolegend), Gr-1 (clone RB6–8C5; Biolegend), F4/80 (clone BM8; Biolegend), CD11c (clone N418; Biolegend), CD8a (clone 53–6.7; Biolegend), CD4 (clone RM4–5; Biolegend) and CD45 (clone 30-F11; Biolegend). For IFN-γ detection, cells were stimulated in vitro with a cell stimulation cocktail (plus protein transport inhibitors) (eBioscience) for 4 hours. Cells were then processed using a fixation and permeabilization kit (BD Bioscience) and stained with antibodies against IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2; eBioscience). For iNOS and arginase1 detection, cells were processed using a fixation and permeabilization kit (eBioscience) and stained with antibodies against iNOS (clone D4E3M; CST) or arginase1 (clone D6B6S; CST). For ROS detection, Cells were incubated in RPMI1640 media containing DCFH-DA (10 μM, Beyotime) for 20 minutes and then stained with the cell surface markers. All samples were acquired using a CantoII flow cytometer (BD) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). An AriaII flow cytometer (BD) was used for cell sorting.

MDSC function

For the analysis of immunosuppressive cytokines stimulated by recombinant mouse C5a (rmC5a), MC38 tumor-bearing mice were killed, and splenic MDSCs were isolated as described previously.30 Splenic MDSCs were stimulated with 100 ng/ml rmC5a for 24 h, and subsequently mRNA was extracted using TRIZOL (Invitrogen), followed by reverse transcription using random hexamers to generate cDNA (Takara). qPCR was performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara) to quantify the relative expression of mRNA. The primers for real-time PCR are listed in Table S1.

T-cell proliferation inhibition was performed as described previously.31 MDSCs were isolated from MC38 tumors of WT and C5aR−/− mice by flow cytometry. Splenocytes were isolated from tumor-free C57BL6 mice using the CD8a+ T-Cell Isolation kit (Stemcells). The isolated T cells were labeled with 5 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen). CFSE-labeled T cells (105) were subsequently plated in a 96-well plate pre-coated with anti-CD3ε antibody (3.5 μg/ml, clone 145–2C11; Biolegend), and soluble anti-CD28 antibody (1.5 μg/ml, clone 37.51; Biolegend) was added to the medium to induce T-cell proliferation with or without MDSCs at the indicated ratios. After 72 h, the cells were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunohistochemistry

Collected tumor and spleen tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 4 μm sections. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the sample in a microwave for 20 min with 10 mM sodium citrate (pH = 6.0). The sections were then incubated in 3% H2O2 for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity, followed by incubating with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight (C1q, clone 7H8, 1:50 dilution, Abcam; C3b/iC3b/C3c, clone 2/11, 1:50 dilution, Hycult Biotech). HRP-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Zhongshan Goldenbridge Biotechnology Company) was used as a secondary antibody and incubate for 30 min at 37 °C. Colorization of the sections was performed by using a DAB kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. and were analyzed using either 2-tailed unpaired t-test or other statistical methods indicated in the text with GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. For all data, * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01 and *** indicates p < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Craig Gerard (Harvard Medical School) for kindly providing C5aR knockout mice and Xiaolan Fu (Third Military Medical University) for technical assistance with flow cytometry. This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 81472648 and No. 81620108023 and No. 31570866).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 81472648 and No. 81620108023 and No. 31570866)

References

- 1.Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8:328rv4; PMID: 26936508; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitt JM, Vetizou M, Daillere R, Roberti MP, Yamazaki T, Routy B, Lepage P, Boneca IG, Chamaillard M, Kroemer G, et al.. Resistance mechanisms to immune-checkpoint blockade in cancer: Tumor-Intrinsic and -extrinsic factors. Immunity 2016; 44:1255-69; PMID: 27332730; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter RR. Structural studies of immunoglobulins. Science (New York, NY) 1973; 180:713-6; PMID:6285180; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.180.4087.713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Gaetano N, Cittera E, Nota R, Vecchi A, Grieco V, Scanziani E, Botto M, Introna M, Golay J. Complement activation determines the therapeutic activity of rituximab in vivo. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2003; 171:1581-7; PMID:12874252; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markiewski MM, Lambris JD. Unwelcome complement. Cancer Res 2009; 69:6367-70; PMID: 19654288; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho MS, Vasquez HG, Rupaimoole R, Pradeep S, Wu S, Zand B, Han HD, Rodriguez-Aguayo C, Bottsford-Miller J, Huang J, et al.. Autocrine effects of tumor-derived complement. Cell Rep 2014; 6:1085-95; PMID: 24613353; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu J, Ding JY, Lu CL, Lin ZW, Chu YW, Zhao GY, Guo J, Ge D. Overexpression of CD88 predicts poor prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2013; 81:259-65; PMID: 23706417; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunkelberger J, Zhou L, Miwa T, Song WC. C5aR expression in a novel GFP reporter gene knockin mouse: implications for the mechanism of action of C5aR signaling in T cell immunity. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2012; 188:4032-42; PMID:22430734; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1103141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbore G, West EE, Spolski R, Robertson AA, Klos A, Rheinheimer C, Dutow P, Woodruff TM, Yu ZX, O'Neill LA, et al.. T helper 1 immunity requires complement-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activity in CD4(+) T cells. Science (New York, NY) 2016; 352:aad1210; PMID: 27313051; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.aad1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markiewski MM, DeAngelis RA, Benencia F, Ricklin-Lichtsteiner SK, Koutoulaki A, Gerard C, Coukos G, Lambris JD. Modulation of the antitumor immune response by complement. Nat Immunol 2008; 9:1225-35; PMID: 18820683; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ni.1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marvel D, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: expect the unexpected. J Clin Invest 2015; 125:3356-64; PMID: 26168215; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI80005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrales L, Ajona D, Rafail S, Lasarte JJ, Riezu-Boj JI, Lambris JD, Rouzaut A, Pajares MJ, Montuenga LM, Pio R. Anaphylatoxin C5a creates a favorable microenvironment for lung cancer progression. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2012; 189:4674-83; PMID:23028051; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1201654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Sun SN, Liu Q, Yu YY, Guo J, Wang K, Xing BC, Zheng QF, Campa MJ, Patz EF Jr., et al.. Autocrine complement inhibits IL10-dependent T-cell mediated antitumor immunity to promote tumor progression. Cancer Discov 2016; 6(9):1022-35; PMID: 27297552; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noman MZ, Desantis G, Janji B, Hasmim M, Karray S, Dessen P, Bronte V, Chouaib S. PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1alpha, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation. J Exp Med 2014; 211:781-90; PMID: 24778419; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20131916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X, Zhang H, Xing Q, Cui J, Li J, Li Y, Tan Y, Wang S. PD-1(+) CD8(+) T cells are exhausted in tumours and functional in draining lymph nodes of colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2014; 111:1391-9; PMID: 25093496; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2014.416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heskamp S, Hobo W, Molkenboer-Kuenen JD, Olive D, Oyen WJ, Dolstra H, Boerman OC. Noninvasive imaging of tumor PD-L1 expression using radiolabeled anti-PD-L1 antibodies. Cancer Res 2015; 75:2928-36; PMID: 25977331; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vadrevu SK, Chintala NK, Sharma SK, Sharma P, Cleveland C, Riediger L, Manne S, Fairlie DP, Gorczyca W, Almanza O, et al.. Complement C5a receptor facilitates cancer metastasis by altering T cell responses in the metastatic niche. Cancer Res 2014; 74(13):3454-65; PMID: 24786787; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soruri A, Kim S, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J. Characterization of C5aR expression on murine myeloid and lymphoid cells by the use of a novel monoclonal antibody. Immunol Lett 2003; 88:47-52; PMID: 12853161; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0165-2478(03)00052-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen SH, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, Mandruzzato S, Murray PJ, Ochoa A, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, et al.. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat Commun 2016; 7:12150; PMID: 27381735; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Draghiciu O, Lubbers J, Nijman HW, Daemen T. Myeloid derived suppressor cells-An overview of combat strategies to increase immunotherapy efficacy. Oncoimmunology 2015; 4:e954829; PMID: 25949858; https://doi.org/ 10.4161/21624011.2014.954829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maenhout SK, Thielemans K, Aerts JL. Location, location, location: functional and phenotypic heterogeneity between tumor-infiltrating and non-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology 2014; 3:e956579; PMID: 25941577; https://doi.org/ 10.4161/21624011.2014.956579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freeley S, Kemper C, Le Friec G. The “ins and outs” of complement-driven immune responses. Immunol Rev 2016; 274:16-32; PMID: 27782335; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/imr.12472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali K, Soond DR, Pineiro R, Hagemann T, Pearce W, Lim EL, Bouabe H, Scudamore CL, Hancox T, Maecker H, et al.. Inactivation of PI(3)K p110delta breaks regulatory T-cell-mediated immune tolerance to cancer. Nature 2014; 510:407-11; PMID: 24919154; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis RJ, Moore EC, Clavijo PE, Friedman J, Cash H, Chen Z, Silvin C, Van Waes C, Allen C. Anti-PD-L1 efficacy can be enhanced by inhibition of myeloid-derived suppressor cells with a selective inhibitor of PI3Kdelta/gamma. Cancer Res 2017; 77:2607-19; PMID: 28364000; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Schadendorf D, Dummer R, Smylie M, Rutkowski P, et al.. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:23-34; PMID: 26027431; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, Sosman JA, Procopio G, Plimack ER, et al.. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1803-13; PMID: 26406148; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L, et al.. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:2018-28; PMID: 25891174; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Donnell JS, Long GV, Scolyer RA, Teng MW, Smyth MJ. Resistance to PD1/PDL1 checkpoint inhibition. Cancer Treat Rev 2017; 52:71-81; PMID: 27951441; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J, Tan Y, Zhang J, Zou L, Deng G, Xu X, Wang F, Ma Z, Zhang J, Zhao T, et al.. C5aR, TNF-alpha, and FGL2 contribute to coagulation and complement activation in virus-induced fulminant hepatitis. J Hepatol 2015; 62:354-62; PMID: 25200905; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, Beckett M, Darga T, Weichselbaum RR, Fu YX. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:687-95; PMID: 24382348; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI67313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chun E, Lavoie S, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Kim J, Soucy G, Odze R, Glickman JN, Garrett WS. CCL2 promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by enhancing polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cell population and function. Cell Rep 2015; 12:244-57; PMID: 26146082; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.