Abstract

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death among females in less developed countries. Studies have shown that the single-nucleotide polymorphisms of interleukin 6 might be associated with cervical cancer risk. A total of 710 articles from EMBASE, EBSCO, Web of science, PubMed, Springer link, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure databases were reviewed in our study. A meta-analysis on the associations between interleukin 6 rs1800795 polymorphism and cervical cancer risk was carried out by comparison using 5 genetic models. In this systematic review, 5 studies were analyzed. The pooled population included 2735 participants (1210 cases and 1525 controls). The overall odds ratio (G vs C alleles) using fixed-effects model was 0.85 (95% confidence interval 0.75-0.97), P = .02. Our results show that the C genotype of interleukin 6 rs1800795 is associated with higher cervical cancer risk. Our results indicate that interleukin 6 rs1800795 polymorphism might be associated with susceptibility to cervical cancer.

Keywords: interleukin 6, polymorphism, cervical cancer, meta-analysis, SNP

Introduction

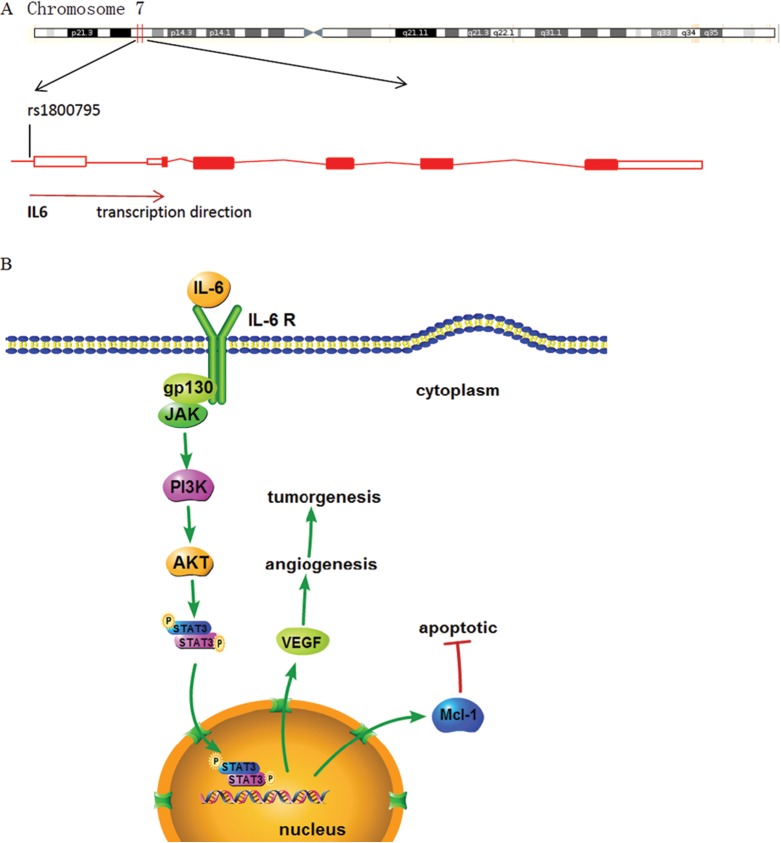

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death among females in less developed countries. Cervical cancer development is closely associated with chronic inflammation caused by infections, such as human papillomavirus (HPV). However, only a small number of women infected with high-risk HPV will develop cervical cancer; therefore, other factors are also involved in cervical cancer development. Studies have suggested that interleukin 6 (IL-6) plays a potential role in cervical cancer. Interleukin 6, originally identified as a B-cell differentiation factor, is a central mediator of inflammation. Interleukin 6 acts as both a proinflammatory cytokine and an anti-inflammatory cytokine in immune response regulation.1 Interleukin 6 is also known to regulate tumor cell growth and antiapoptosis process. Earlier studies have demonstrated that IL-6 facilitates cervical tumor growth via vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-dependent angiogenesis2 or by modulating the apoptosis threshold3 (Figure 1). However, the mechanism of IL-6 regulation is still unclear. Many factors, such as single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), may affect gene expressions. For example, the SNPs located in exons might change the codons, whereas the SNPs located in introns might cause transcriptional frequency distinction. Moreover, certain genotypes of IL-6 polymorphism might have a higher risk of developing cervical cancer.4 However, some studies show a negative association between IL-6 polymorphism and cervical cancer risk.5 Here, we conducted a meta-analysis of the associations between IL-6 polymorphism and cervical cancer risk.

Figure 1.

The location of IL-6 rs1800795 polymorphism and mechanism. A, Interleukin 6 rs1800795 polymorphism is located at the upstream of IL-6 gene promoter in human chromosome 7. B, Interleukin 6 facilitates tumor growth and reduces apoptosis by upregulating VEGF and Mcl-1 level, respectively, via STAT3 pathway. IL-6 indicates interleukin 6; JAK, Janus kinases; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; Mcl-1, myeloid cell leukemia 1.

Materials and Methods

Literature Review

A presearch strategy was performed before literature review using “interleukin, polymorphism, cervical cancer” as key words. Fifty-eight articles were identified in PubMed. Interleukin 6 was chosen as the target gene based on abstract reviewing process. We searched several databases, including EBSCO, EMBASE, Web of science, PubMed, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, to extract articles that referred to the association between the IL-6 polymorphism and cervical cancer risk up until July 2015. The key words used for the research were as follows: cervical cancer, cervical carcinoma, cervical tumor, uterine cervix cancer, interleukin-6, IL-6, SNP, polymorphism, allele.

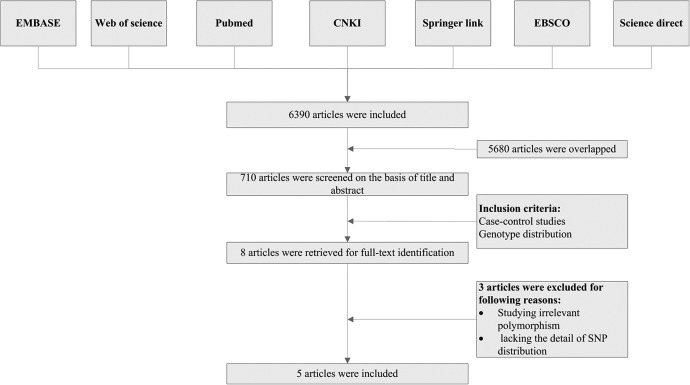

After excluding duplicates, book chapters, and conference abstracts, the titles and abstracts of the selected articles were reviewed for extraction. The inclusion criteria were (1) case–control studies and (2) containing genotype distribution data. The exclusion criteria were (1) review articles, (2) not related to IL-6, or (3) not a human study. The selection process is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart showing the study selection procedure. CNKI indicates China National Knowledge Infrastructure.

Data Extraction

For each study, the name of the first author, the year of publication, country of origin, age of participants, race of study population, and genotyping method were extracted (Table 1). Distributions of genotypes in both cases and controls are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Analysis.

| Authors | Year of Publication | Country | Host Ethnicity | Age, Mean ± SD or Median, years | Samples, n | Genotyping Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | |||||

| Lima Júnior and Crovella11 | 2012 | Brazil | Multiethnicity | – | – | 345 | 345 | PCR sequencing |

| Shi et al4 | 2014 | China | Han Chinese | 55.2 ± 10.1 | 54.9 ± 9.8 | 518 | 518 | PCR-RFLP |

| Gangwar et al9 | 2009 | India | Indian | 45.0 | 46.0 | 160 | 200 | ARMS-PCR |

| Grimm et al5 | 2011 | Austria | Caucasian | 31.1 ± 7.9 | 34.6 ± 12.0 | 131 | 209 | PCR pyrosequencing |

| Nogueira de Souza et al10 | 2006 | Finland | Caucasian | 52.2 ± 13.4 | 54.0 ± 6.9 | 56 | 253 | PCR-RFLP |

Abbreviations: ARMS, amplification refractory mutation system; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Genotype and Allele Distribution of IL-6 1800795 Polymorphism in Cervical Cancer Cases and Controls.

| Study | Case | Control | Country | HWE, χ | P Value | OR (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | GC | CC | G | C | GG | GC | CC | G | C | |||||

| Lima Júnior and Crovella11 | 72 | 39 | 4 | 183 | 47 | 67 | 37 | 11 | 171 | 59 | Brazil | 2.82 | .09 | 1.34 (0.87-208) |

| Shi et al4 | 160 | 253 | 105 | 573 | 463 | 181 | 259 | 78 | 621 | 415 | China | 0.88 | .35 | 0.83 (0.69-0.98) |

| Gangwar et al9 | 107 | 36 | 17 | 250 | 70 | 142 | 51 | 7 | 335 | 65 | India | 0.79 | .37 | 0.69 (0.48-1.01) |

| Grimm et al5 | 55 | 51 | 25 | 161 | 101 | 85 | 96 | 27 | 266 | 150 | Austria | 0.01 | .99 | 0.90 (0.65-1.24) |

| Nogueira de Souza et al10 | 24 | 32 | 0 | 80 | 32 | 148 | 120 | 3 | 416 | 126 | Finland | 15.72 | .001 | 0.76 (0.48-1.19) |

| Overall | 0.85 (0.75-0.97) | |||||||||||||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium; IL-6, interleukin 6; OR, odds ratio.

Statistical Analyses

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was examined in controls by asymptotic Pearson χ2 test for each polymorphism in each study. The association between polymorphism and cervical cancer risk was estimated with odds ratios (ORs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity between studies was tested using Q test and I2 test. The heterogeneity was considered significant if P value was less than .05. Fixed-effects model was adopted when P value was more than .05; otherwise, random-effects models was used.6 The publication bias was evaluated using Begg test and Egger test.7,8 P <.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 13.0 (College Station, Texas).

Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis was performed based on the data from the International Hap Map Project (HapMap3 Genome Browser release #2, phase 3—genotypes, frequencies, and LD). Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry (CEU) were chosen in this LD analysis. A total of 4-kb D′ and r2 values for IL-6 SNPs were calculated by Haploview 4.2 (Mark Daly’s Lab, Broad Institute, Cambridge). r2 > .8 was considered a significant LD.

Results

A total of 6390 articles were obtained from the literature search. As shown in Figure 2, 710 articles were reviewed after excluding the duplicates, book chapters, and conference abstracts. A total of 8 research articles that reported the association of human IL-6 polymorphisms and cervical cancer risk were identified. Three of them were excluded after reviewing the full-text article, because they were studying irrelevant SNP or lacking detailed SNP distribution data. Finally, 5 studies from 5 articles were included in this analysis. Four of the articles were published in English,4,5,9,10 and 1 article was published in Portuguese.11 As described above, distributions of genotypes in both cases and controls were extracted (Table 2).

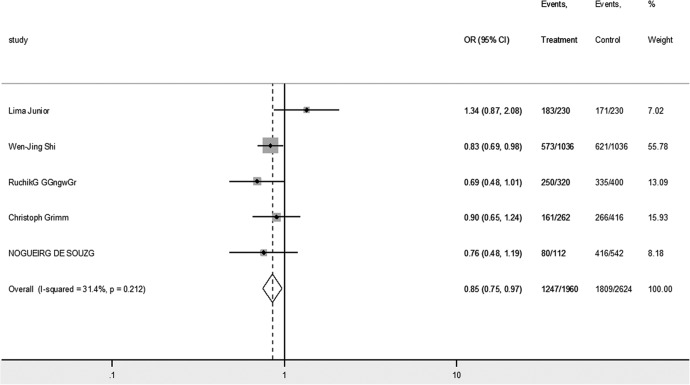

Overall, 5 different genetic models (allele, heterozygote, homozygote, dominant, and recessive model) were analyzed to address the relationship between IL-6 rs1800795 polymorphism and the risk of cervical cancer. As shown in Table 3, the heterogeneity was not significant in the study on Finnish population10 (P = .21, I2 = 31.4%). The overall OR (G vs C alleles) using fixed-effects model was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.75-0.97), P = .02, suggesting G genotype reduced the risk of cervical cancer (Figure 3). Hence, the females with at least 1 C genotype are more susceptible to cervical cancer. Analyses of other genetic models were also performed, but no association was identified. The publication bias was negligible in these genetic models (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of Different Models in Meta-Analysis Results.

| SNP | Genetic Model | Participants | OR (95% CI) | Z | P Value | I2 (%) | P het | Effects Model | Begg Test | Egger Test | Peter test | Harbord Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1800795 | GG vs GC + CC | 2285 | 0.73 (0.43-1.26) | 1.12 | .26 | 86.8 | <.001 | Random | .14 | .13 | .17 | .14 |

| CC vs GC + GG | 2285 | 1.53 (0.75-3.12) | 1.17 | .24 | 74.3 | .004 | Random | .99 | .82 | .76 | .88 | |

| GG vs GC | 2008 | 0.79 (0.47-1.32) | 0.91 | .37 | 83.8 | <.001 | Random | .05 | .07 | .11 | .06 | |

| GG vs CC | 1311 | 0.62 (0.26-1.51) | 1.05 | .29 | 81.4 | <.001 | Random | .62 | .61 | .67 | .67 | |

| G vs C | 4584 | 0.85 (0.752-0.97) | 2.44 | .02 | 31.4 | .21 | Fixed | .99 | .69 | .46 | .72 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; Phet, P value for heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the association between IL-6 rs1800795 polymorphism and cervical cancer risk in allele comparison (G vs C). IL-6 indicates interleukin 6.

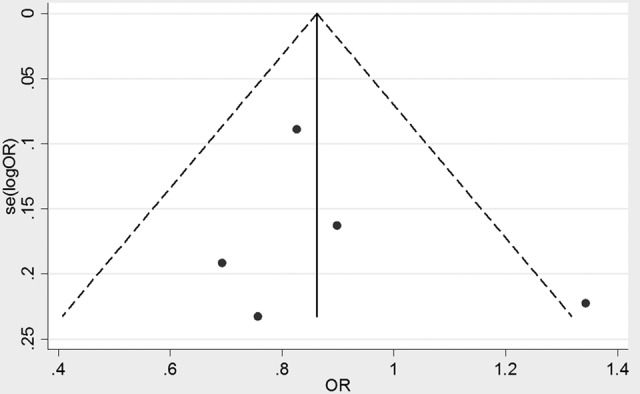

Furthermore, all studies on IL-6 rs1800795 and the risk for cervical cancer were analyzed for the deviation from HWE. As shown in Table 2, all studies deviated from the HWE (P < .01), except for the study in Finland population.10 The funnel chart is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of meta-analysis.

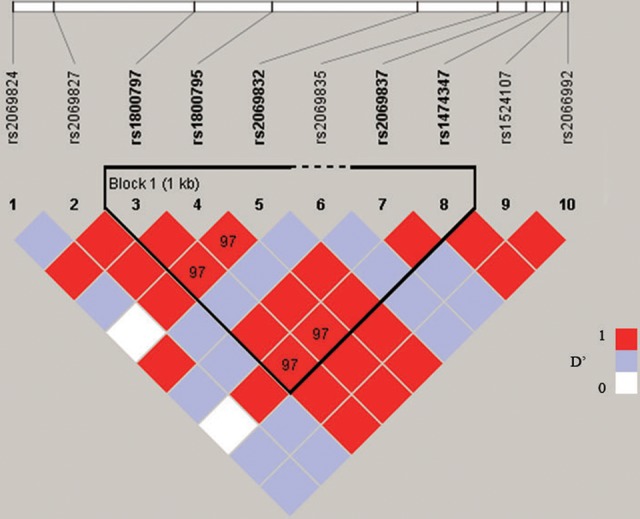

The LD pattern in the 4-kb upstream and downstream of the rs1800795 on chromosome 7 was investigated in our study. One haplotype block was identified in the CEU population. The rs1800795 showed LD with rs1800797 (D′ = 1.0, r2 = .979), rs2069832 (D′ = 0.978, r2 = .957), rs2069837 (D′ = 1.0, r2 = .099), and rs1474347 (D′ = 0.978, r2 = .936) in this block (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A linkage disequilibrium plot in the region of IL-6. IL-6 indicates interleukin 6.

Discussion

Recent studies have shown that IL-6 is a tumor cell growth regulator and an antiapoptotic mediator. Interleukin 6 activates the Janus kinases/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signal pathway in several types of cancers.12–14 Interleukin 6 is capable of driving VEGF promoter via a STAT3 pathway in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (Figure 1).2 A study on C33A/IL-6-c5 cell line suggests that IL-6 mediates human cervical tumor cell apoptotic resistance by upregulating Mcl-1 (myeloid cell leukemia 1) level via STAT3 pathway.3 In this study, we performed a meta-analysis to assess the association between IL-6 rs1800795 SNP and cervical cancer risk. We analyzed 5 different genetic models (allele, heterozygote, homozygote, dominant, and recessive model) in IL-6 rs1800795 polymorphism. A subgroup analysis by race was also performed. On the basis of 2292 participants (980 cases and 1312 controls), our analysis indicates that the genotypes of IL-6 rs1800795 polymorphism are associated with cervical cancer risk.

Our results suggest that IL-6 gene polymorphism may play a significant role in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer. Interleukin 6 rs1800795 is located at the 174 base pair upstream of IL-6 gene promoter. Based on LD analysis, 2 SNPs (rs1800795 and rs1800797) in the upstream of IL-6 gene promoter and 3 SNPs (rs2069832, rs2069837, and rs1474347) in the IL-6 introns showed LD with each other and formed a haplotype block. These results indicate that these SNPs tend to pass as a haplotype from 1 generation to the next and might be able to regulate IL-6 transcription or posttranscriptional modification.15 Therefore, these 5 SNPs will follow the same inherited pattern and tend to pass through the generations as a block. One study shows that rs1800797 was not associated with cervical cancer in the Swedish population.16 However, we did not find any studies that focused on the correlation of rs2069832, rs2069837, or rs1474347 and cervical cancer during the literature review. Hence, more experiments with a larger sample size and more SNP sites should be performed to confirm our finding.

The association of rs1800797 and the risk of cervical cancer is consistent in the individual studies. For examples, rs1800797 confers higher risk of cervical cancer in Han Chinese in Shi’s study.4 However, the rs1800797 polymorphism is not a risk factor for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in Caucasian in the Grimm’s study.5 In our meta-analysis, we reviewed 5 case–control studies including 1210 cases and 1525 controls. Our review included Han Chinese, Brazilians, Indians, and Caucasians. Therefore, our study is a comprehensive analysis of rs1800797 polymorphism and the risks of cervical cancer.

The present study was performed through scientific and rational design. However, it has several limitations. Firstly, although Begger funnel plot analysis did not show the presence of publication bias, there may still be selective language bias, since this study only included documents published in English and Portuguese. Secondly, due to the small sample size of the included studies, we did not perform subgroup analyses to clarify its association with IL-6 gene. Finally, the potential confounding factors, such as race, age, and geographical distribution, may exist in this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results indicate that the C genotype of IL-6 rs1800795 polymorphism might be associated with higher cervical cancer risk. The conclusion is different from the individual studies.4,5

Abbreviations

- ARMS

amplification refractory mutation system

- CI

confidence intervals

- CNKI

Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- JAK

Janus kinases

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- OR

odds ratios

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- Phet

P value for heterogeneity

- RFLP

restriction fragment length polymorphism

- SD

standard deviation

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by PLA General Logistics Department of the Ministry of Health (No. 13QNP030).

Reference

- 1. Ishihara K, Hirano T. IL-6 in autoimmune disease and chronic inflammatory proliferative disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13(4-5):357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wei LH, Kuo ML, Chen CA, et al. Interleukin-6 promotes cervical tumor growth by VEGF-dependent angiogenesis via a STAT3 pathway. Oncogene. 2003;22(10):1517–1527. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1206226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wei LH, Kuo ML, Chen CA, et al. The anti-apoptotic role of interleukin-6 in human cervical cancer is mediated by up-regulation of Mcl-1 through a PI 3-K/Akt pathway. Oncogene. 2001;20(41):5799–5809. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shi WJ, Liu H, Wu D, Tang ZH, Shen YC, Guo L. Stratification analysis and case-control study of relationships between interleukin-6 gene polymorphisms and cervical cancer risk in a Chinese population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(17):7357–7362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grimm C, Watrowski R, Baumuhlner K, et al. Genetic variations of interleukin-1 and -6 genes and risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(3):537–541. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kavvoura FK, Ioannidis JP. Methods for meta-analysis in genetic association studies: a review of their potential and pitfalls. Hum Genet. 2008;123(1):1–14. doi:10.1007/s00439-007-0445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Begg CB, Berlin JA. Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(2):107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gangwar R, Mittal B, Mittal RD. Association of interleukin-6-174G>C promoter polymorphism with risk of cervical cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2009;24(1):11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nogueira de Souza NC, Brenna SM, Campos F, Syrjanen KJ, Baracat EC, Silva ID. Interleukin-6 polymorphisms and the risk of cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(3):1278–1282. doi:0.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lima Júnior SFd, Crovella SO. Avaliação dos polimorfismos nos genes das citocinas IL 6 (RS 1800795) e TGF-β (RS 1982073) e RS 1800471) e suas relações com o grau de lesão cervical em pacientes infectados pelo Papillomavírus humano. Recife: Universidade Faderal de Pernambuco, Dissertação De Mestrado; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abdul Rahim SN, Ho GY, Coward JI. The role of interleukin-6 in malignant mesothelioma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4(1):55–66. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2014.07.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Waldner MJ, Foersch S, Neurath MF. Interleukin-6—a key regulator of colorectal cancer development. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(9):1248–1253. doi:10.7150/ijbs.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berishaj M, Gao SP, Ahmed S, et al. Stat3 is tyrosine-phosphorylated through the interleukin-6/glycoprotein 130/Janus kinase pathway in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(3):R32 doi:10.1186/bcr1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhu X, Zhang S, Kan D, Cooper R. Haplotype block definition and its application. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2004:152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castro FA, Haimila K, Sareneva I, et al. Association of HLA-DRB1, interleukin-6 and cyclin D1 polymorphisms with cervical cancer in the Swedish population—a candidate gene approach. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(8):1851–1858. doi:10.1002/ijc.24529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]