Abstract

Arguments opposing same-sex marriage are often made on religious grounds. In five studies conducted in the United States and Canada (combined N = 1,673), we observed that religious opposition to same-sex marriage was explained, at least in part, by conservative ideology and linked to sexual prejudice. In Studies 1 and 2, we discovered that the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage was mediated by explicit sexual prejudice. In Study 3, we saw that the mediating effect of sexual prejudice was linked to political conservatism. Finally, in Studies 4a and 4b we examined the ideological underpinnings of religious opposition to same-sex marriage in more detail by taking into account two distinct aspects of conservative ideology. Results revealed that resistance to change was more important than opposition to equality in explaining religious opposition to same-sex marriage.

Keywords: religiosity, conservatism, system justification, sexual prejudice, same-sex marriage

[T]he attack we are currently experiencing on the true structure of the family, made up of father, mother, and child, goes much deeper . . .

Despite an improving legal landscape for sexual minorities, negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women persist in North America, and same-sex marriage remains a topic of considerable debate (Waters, Jindasurat, & Wolfe, 2016). Arguments opposing same-sex marriage are often made on religious grounds. Although the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage has been noted often in mainstream media and academic outlets (Babst, Gill, & Pierceson, 2009), the question of why people oppose same-sex marriage has not been adequately addressed at the level of social, personality, and political psychology. In the current research program, we investigated whether religious opposition to same-sex marriage has ideological roots in the desire to maintain the societal status quo. Despite the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in 2015 to legalize same-sex marriage (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015), resistance lingers in the United States and elsewhere. Therefore, the psychological processes underlying religious and ideological opposition to same-sex marriage are of considerable theoretical and practical interest.

In this article, we draw on the theory of political ideology as motivated social cognition (Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloway, 2003) and system justification theory (Jost & Banaji, 1994; Jost & van der Toorn, 2012) to shed light on the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage. Specifically, we examine a model in which religious opposition to same-sex marriage is, at least in part, accounted for by sexual prejudice and motivated by conservative tendencies to defend the status quo. In five studies conducted in Canada and the United States, we investigated the hypotheses that religiosity would be related to opposition to same-sex marriage through sexual prejudice (Hypothesis 1), and that these effects would be explained, at least in part, by endorsement of conservative ideology (Hypothesis 2), with resistance to change being a more important factor than opposition to equality (Hypothesis 3).

Religiosity and the Same-Sex Marriage Debate

Since 1996, the Gallup organization has tracked opinions about whether marriages between same-sex couples should be recognized by the law. In 1996, two thirds of Americans opposed legalized same-sex marriage, but by 2004 support had risen to 42% and, despite some fluctuations from year to year, increased to 55% in 2014 (McCarthy, 2014). Despite a general increase in support, many religious groups have actively opposed the legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States. Christian arguments against same-sex marriage tend to be based upon Biblical passages such as those discussing the fate of Sodom (Genesis 19:24-25). Specifically, these command that one “not lie with mankind, as with womankind; it is an abomination” (Leviticus 18:22), and state that those who do “shall surely be put to death” (Leviticus 20:13). Pope Benedict XVI considered same-sex marriage to be among “the most insidious and dangerous threats to the common good today” (Winfield, 2010) and homosexuality an “inherent moral evil” (Popham, 2005). Although the current Pope, Francis, holds a somewhat more welcoming attitude toward sexual minorities, he has done little to undo the Catholic Church’s official condemnation of same-sex marriage (Wofford, 2014).

Much as some religious groups played a key role in the civil rights movement, there are denominations that now support full legal and religious marriage equality for gay and lesbian couples. The United Church of Christ is one example. In arguing for marriage equality, they refer to the Christian values of love, peace, and compassion. On average, however, religiosity is associated with opposition to same-sex marriage, whether religiosity is measured in terms of the centrality of religion to one’s life or the extent of engagement in religious practices. For example, the more importance people ascribe to religion in their lives, the more likely they are to oppose same-sex marriage (Jones, 2010). In a survey conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (2003), 80% of respondents with high levels of religious commitment opposed same-sex marriage (see also Olson, Cadge, & Harrison, 2006; Sherkat, Powell-Williams, Maddox, & de Vries, 2011; Swank & Raiz, 2010; Whitehead, 2010). Gallup data from 2012 revealed that individuals who attended church on a weekly basis were more likely to be against recognition of same-sex marriage than people who attended less often or never (Newport, 2012). Furthermore, those who opposed legalization of same-sex marriage were especially likely to justify their position on the basis of religious belief or interpretations of the Bible (Newport, 2012).

As federal legalization of same-sex marriage became increasingly probable in the United States, the debate on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights shifted from a focus on discrimination by the government to discrimination by the private sector (Johnson, 2015), with religious arguments dominating the rhetoric of those opposing same-sex marriage. New York legalized same-sex marriage in 2011 but not before special provisions were made for religious protections within the text of the law. These protections were intended to make it clear that the bill does not require anyone to perform or solemnize marriages against their will. After the bill passed, a senior lobbyist opposed to same-sex marriage stated that “the amendment language does nothing to protect cake bakers, caterers, photographers, florists, or other people of strong religious faith opposed to same-sex ‘marriage’ that refuse to provide services for same-sex couples” (Katz, 2011). Statements such as these make an explicit connection between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage, and they demonstrate the deeply personal manner in which the issue is played out.

Sexual Prejudice as a Mediator of Religious Opposition to Same-Sex Marriage

Whereas religious opponents may see their objections to same-sex marriage as principled and legitimate, others see it as a human rights issue and may interpret opposition as a form of sexual prejudice and discrimination. Empirically speaking, religious opposition to same-sex marriage could stem from various sources. Given that religion offers believers a well-defined moral framework that entails specific attitudes toward social groups, beliefs, and behaviors, it is possible that attitudes toward same-sex marriage simply reflect religious proscriptions. On the other hand, opposition may also be driven by sexual prejudice, which is defined as antipathy toward individuals and groups based on their sexual orientation (Herek, 2000). An initial aim of this research program was to investigate whether a general aversion to gay men and lesbian women helps explain the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage. Previous research has demonstrated that religiosity is associated with sexual prejudice (Herek & McLemore, 2013) and opposition to same-sex marriage (Herek, 2011). To our knowledge, however, no studies have investigated the hypothesis that religious opposition to same-sex marriage is attributable, at least in part, to sexual prejudice (Hypothesis 1).

Conservative Ideology and the Same-Sex Marriage Debate

Political ideology is also associated with sexual prejudice, with conservatives exhibiting more sexual prejudice than liberals (Barth & Parry, 2009; Haslam & Levy, 2006; Whitley, 1999; see also Pacilli, Taurino, Jost, & van der Toorn, 2011). Blenner (2015) demonstrated that experimentally heightening preferences to maintain the status quo (through a system justification manipulation) worsened participants’ views of lesbians and gay men. Analyzing 20 years of data from the General Social Survey, Sherkat and colleagues (2011) observed that political conservatives and those who identified with the Republican Party were more resistant to same-sex marriage than other Americans. For the first time in Gallup’s tracking of the issue, a majority (53%) of Americans in 2011 expressed the opinion that same-sex marriage should be legalized (Newport, 2012). The increase from previous years was driven more or less exclusively by Democrats and Independents; the views of Republicans did not change (Newport, 2011). By 2014, clear majorities of Democrats (74%) and Independents (58%) supported same-sex marriage, but only 30% of Republicans supported it (McCarthy, 2014). Therefore, a second aim of our research was to investigate whether the effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage would be mediated by the endorsement of conservative ideology.

Specifically, we hypothesized that political conservatism and sexual prejudice would mediate the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage in serial fashion, such that Religiosity → Political Conservatism → Sexual Prejudice → Opposition to Same-Sex Marriage (Hypothesis 2). We specified this ordering of variables because specific intergroup attitudes (sexual prejudice) are assumed to be more proximal to public policy preferences (same-sex marriage) than more general ideological dispositions (see Jost, Nam, Amodio, & Van Bavel, 2014). Because previous research has demonstrated a robust connection between political conservatism and system justification (Jost et al., 2017), we treated these ideological variables as largely interchangeable in the present research context.

Core Aspects of Conservative Ideology

According to a prominent model of political ideology, the two core aspects of conservatism are resistance to change and opposition to equality (Jost, 2006; Jost et al., 2003). Ideological self-placement on a single left–right dimension is correlated with prejudice toward nonnormative groups, such as gay men and lesbian women (e.g., Luguri, Napier, & Dovidio, 2012). Nevertheless, somewhat distinct processes are thought to underlie resistance to change and opposition to equality. Right-wing authoritarianism (Altemeyer, 1988)—which taps into resistance to change (Jost et al., 2003)—is associated with prejudice against groups that violate social conventions, whereas social dominance orientation (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994)—which relates more clearly to opposition to equality (Jost et al., 2003)—is associated with prejudice toward groups that are perceived as inferior (Jost & Thompson, 2000). Previous research shows that both right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation predict sexual prejudice (Poteat, Espelage, & Green, 2007; Pratto et al., 1994; Whitley, 1999).

The link between religiosity and resistance to change is fairly evident, insofar as religions tend to value traditionalism and maintenance of the societal status quo (i.e., system justification; see Jost et al., 2014). As one sociologist puts it, “Established religious institutions have generally had a stake in the status quo and hence have supported conservatism” (Marx, 1967, p. 64). At the same time, religious doctrine emphasizes values such as compassion and tolerance, which seem more consistent with supporting marriage equality than opposing it. Therefore, we anticipated that resistance to change might be more important than opposition to equality in accounting for the positive association between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage. Consistent with this theoretical logic, right-wing authoritarianism seems to be a stronger predictor of sexual prejudice than social dominance orientation (Haddock, Zanna, & Esses, 1993; Haslam & Levy, 2006). Thus, we reasoned that resistance to change would be a stronger mediator of the effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage, in comparison with opposition to equality (Hypothesis 3).

Overview of Studies

In this research program, we sought to elucidate the effects of religiosity, political conservatism, and sexual prejudice in accounting for opposition to same-sex marriage. To do this, we needed to establish that religiosity is indeed positively related to opposition to same-sex marriage, and to understand the extent to which this relationship is explained by sexual prejudice. Therefore, in Studies 1 and 2, we addressed the question of whether the effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage is mediated by sexual prejudice. In Study 3, we more closely examined the ideological underpinnings of these effects, and investigated whether preferences for the status quo (i.e., political conservatism) also mediate the effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage. In Studies 4a and 4b, we distinguished between the two core components of conservative ideology, resistance to change and opposition to equality, and tested whether the effect of the former is stronger than that of the latter. Some of the direct relationships among these variables have been explored in prior studies, but our work contributes significantly to the psychological literature by investigating these variables simultaneously in an integrated theoretical model that enables us to explore indirect relationships as well.

Analysis Plan

We investigated our hypotheses with mediation analyses using Hayes’s (2013) PROCESS macro for SPSS based on 10,000 bootstrap resamples. In Study 1, we conducted a bootstrapping analysis for simple mediation models (Hayes, 2013, Model 4); in Study 2, we conducted a bootstrapping analysis for parallel multiple mediation models (Hayes, 2013, Model 4); and in Studies 3, 4a, and 4b we conducted a bootstrapping analysis for serial multiple mediation models (Hayes, 2013, Model 6). All confidence intervals for the indirect effects are 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals.

It is important to note that, given the observational nature of our research, it is impossible to infer causality. Mediation analysis can be used to test the significance of a variable as a possible causal mediator, but it cannot tell us whether the variable is in fact a causal mediator (Fiedler, Schott, & Meiser, 2011; Wiedermann & von Eye, 2015). Comparing our model with an alternative in which the order of variables is altered does not provide strong evidence that one model should be preferred over the other (Thoemmes, 2015). Nevertheless, at the request of journal reviewers, we provide the results of plausible alternative models in an online supplement. Because it is difficult, if not impossible, to manipulate research participants’ levels of religiosity, we rely on the assumption that religiosity generally precedes sexual prejudice rather than the other way around. This assumption is in line with existing theory and research as well as common sense. We hasten to add, in any case, that it is empirically possible for our mediation hypotheses to be contradicted by the data.

Study 1

Method

Participants and procedure

One hundred fifty heterosexual undergraduate students at the University of Toronto (Mage = 18.91, SD = 2.74; 113 females) participated for course credit.1 Data were collected in 2004, in the months before national same-sex marriage legislation was passed by the Canadian House of Commons. Participants completed a questionnaire in the laboratory, which included measures assessing participants’ religiosity, their explicit sexual prejudice, and their attitudes toward same-sex marriage.2

Materials

For more information concerning the materials and procedures for all studies included in this article, consult our project page on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/phu4v/?view_only=6a6d75b425334def86d67fbe80de0107

Religiosity

Participants were asked to indicate their religiosity on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all religious) to 7 (extremely religious).

Sexual prejudice

Participants’ explicit attitudes were measured using items from the Attitudes Toward Gay Men subscale (ATGM; Herek, 1994). Participants indicated their agreement with eight statements on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items included “Homosexual behavior between two men is just plain wrong” and “Just as in other species, male homosexuality is a natural expression of sexuality in human men” (reverse coded; α= .88). This subscale did not include any items related to same-sex marriage.

Opposition to same-sex marriage

Participants’ attitudes toward same-sex marriage were measured in terms of support for the federal policy issue “gay marriage” (1 = very negative, 7 = very positive; reverse scored), which was embedded within a list of 10 controversial policies in order to disguise the intent of the measure. (Other policy issues included “income tax cuts,” “sending the Canadian military to Iraq,” and “implementing the Kyoto Protocol.”)

Results

Descriptive statistics are provided in Table A in the online supplement. Religiosity was positively correlated with explicit sexual prejudice, r(148) = .402, p < .001, as well as opposition to same-sex marriage, r(148) = .461, p < .001. Sexual prejudice was positively correlated with opposition to same-sex marriage, r(148) = .787, p < .001.

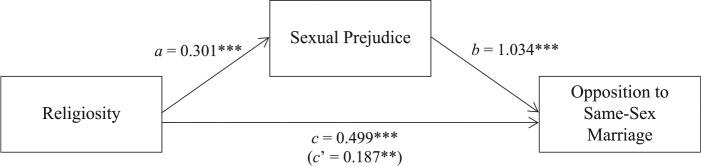

To investigate our first hypothesis—that sexual prejudice would mediate the effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage—we conducted a mediation analysis (see Table B in the online supplement for regression estimates). As depicted in Figure 1, religiosity indirectly influenced opposition to same-sex marriage through its effect on sexual prejudice. To the extent that participants were more religious, they were also more prejudiced (a = 0.301), and to the extent that participants were more prejudiced they were more opposed to same-sex marriage (b = 1.035). The confidence interval for the indirect effect (ab = 0.312) was above 0 [0.194, 0.437], abcs = 0.288. These findings support the first hypothesis. There was also evidence that religiosity influenced opposition to same-sex marriage independent of its effect on sexual prejudice (c’ = 0.187, p = .002).3

Figure 1.

Simple mediation model for Study 1.

Note. **p < .01, ***p < .001

Study 2

Study 1 demonstrated that religiosity predicted opposition to same-sex marriage through sexual prejudice, as hypothesized. At the same time, the fact that religiosity remained significant when sexual prejudice was entered into the model suggests that it also exerted an independent effect on opposition to same-sex marriage. Based on the logic of social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) and self-categorization (Turner, 1987) theories, we deemed it plausible that religiosity might affect opposition to same-sex marriage because of ingroup bias. That is, if religious people identify and self-categorize as heterosexuals or believe that truly religious people are heterosexual, their opposition to same-sex marriage could simply reflect the denial of privileges to members of an outgroup. To address this possibility, in Study 2 we also considered the mediating influence of participants’ identification with the heterosexual ingroup, their self-categorization as heterosexual, and the extent to which they perceived overlap between heterosexual and religious category memberships. We also administered a more general measure of sexual prejudice (rather than aversion to gay men in particular) and examined self-reported willingness to protest against same-sex marriage.4

Method

Participants and procedure

Two hundred twelve heterosexual undergraduate students at the University of Toronto (Mage = 19.46, SD = 3.93; 164 females) participated for course credit in 2005. Participants completed a questionnaire in the laboratory, which included measures of religiosity, sexual prejudice, willingness to protest against same-sex marriage, heterosexual ingroup identification, heterosexual self-categorization, and perceived category overlap.5

Materials

Religiosity

Participants indicated their religiosity on a continuum ranging from 1 (not at all religious) to 7 (extremely religious).

Sexual prejudice

Sexual prejudice was measured using a modified version of the eight-item scale administered in Study 1 (ATGM; Herek, 1994). Sample items, which were worded more broadly than in the original scale, included the following: “Homosexual behavior between two people is just plain wrong” and “Just as in other species, homosexuality is a natural expression of sexuality in humans” (reverse scored). Participants indicated their agreement on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree; α = .92).

Ingroup bias

On 7-point scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), participants indicated their agreement with four ingroup identification items (e.g., “I am proud of my sexual orientation” and “My sexual orientation is important to me; α = .74), and two self-categorization items (“I often feel aware of my sexual orientation” and “I think of myself in terms of my sexual orientation”; r(210) = .32, p < .001).6 Finally, perceived category overlap was measured with the following item: “I think that all truly religious people are heterosexuals.”

Willingness to protest against same-sex marriage

Participants’ willingness to engage in action supporting versus opposing same-sex marriage and related rights was measured using five items on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all willing, 7 = extremely willing). Three were opposing actions: “Donate to an organization that opposes giving homosexuals more rights,” “Sign a petition against gay marriage,” and “Send a letter to the government opposing gay marriage.” Two were supportive actions: “Ask other people to support a petition in favor of gay marriage” and “Join a protest supporting more rights for homosexuals.” The latter two items were reverse scored, and responses were averaged to create an index, so that higher scores indicated greater willingness to protest against same-sex marriage or less willingness to protest on behalf of same-sex marriage (α= .81).

Results

Descriptive statistics are provided in Table C of the online supplement. Religiosity was positively correlated with sexual prejudice, r(210) = .418, p < .001, and with willingness to protest against same-sex marriage, r(210) = .459, p < .001. Sexual prejudice was positively correlated with willingness to protest, r(210) = .843, p < .001. Of the three measures of ingroup bias, only perceived category overlap was positively correlated with religiosity, r(210) = .276, p < .001, and willingness to protest, r(210) = .520, p < .001. Therefore, we included perceived category overlap as a potential mediator of the relationship between religiosity and willingness to protest against same-sex marriage (see Table D in the online supplement).

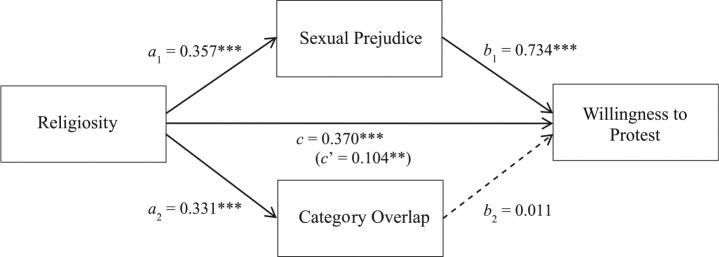

As depicted in Figure 2, religiosity indirectly influenced willingness to protest through its effect on sexual prejudice. Participants who were more religious were more prejudiced (a1 = 0.357) and, in turn, more willing to protest against same-sex marriage (b1 = 0.734). The confidence interval for the indirect effect (a1b1 = 0.262) was above 0 [0.185, 0.344], a1b1cs = 0.326. However, perceived category overlap failed to mediate the relationship between religiosity and willingness to protest. The confidence interval for the indirect effect (a2b2 = 0.004) included 0 [−0.015, 0.027], a2b2cs = 0.004. There was again evidence that religiosity influenced willingness to protest independent of its effect on sexual prejudice (c′ = 0.104, p = .001).7

Figure 2.

Parallel multiple mediator model for Study 2.

Note. ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

In a conceptual replication of Study 1 with a measure of behavioral intention, we obtained additional support in Study 2 for the hypothesis that religiosity would predict willingness to protest against same-sex marriage, and that this relationship would be mediated by sexual prejudice. In addition, we learned that the relationship between religiosity and willingness to protest was not mediated by heterosexual ingroup identification, heterosexual self-categorization, or perceived category overlap; thus, ingroup bias does not appear to account for religious opposition to same-sex marriage.

Study 3

Although the results of our first two studies suggested that the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage was explained in part by sexual prejudice rather than ingroup bias, specific mechanisms remained somewhat obscure. Based on system justification theory (Jost et al., 2014) and the model of political conservatism as motivated social cognition (Jost et al., 2003), we hypothesized that religiosity, sexual prejudice, and opposition to same-sex marriage would be linked to a politically conservative tendency to justify the societal status quo. Our reasoning was consistent with prior research, indicating that religiosity and conservatism are associated with system justification (Jost et al., 2014; Jost et al., 2017) as well as sexual prejudice (Barth & Parry, 2009; Haslam & Levy, 2006; Herek & McLemore, 2013), and opposition to same-sex marriage (Herek, 2011; Sherkat et al., 2011). In Study 3, which was conducted in the United States, we investigated the hypothesis that the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage would be serially mediated by the endorsement of conservative ideology and sexual prejudice.8

Method

Participants and procedure

In the fall of 2012, we administered an online survey to 449 heterosexual undergraduate students (Mage = 18.98, SD = 1.21; 326 females) who participated in a mass-testing session at New York University. A plurality of participants identified as Christian, Catholic, or Protestant (38.8%), and 22.7% identified with another religion. Of the rest, 22.7% identified themselves as atheist and 15.8% as agnostic. Participants completed measures of religiosity, political ideology, sexual prejudice, and opposition to same-sex marriage, and provided demographic information. The scales were administered in a random order.

Materials

Political ideology

We assessed participants’ ideology by asking them to place themselves on a scale ranging from 1 (extremely liberal) to 11 (extremely conservative).

Religiosity

Participants indicated the strength of their religious conviction by responding to the item: “How religious are you?” (1 = not at all religious, 7 = extremely religious).

Sexual prejudice

We administered the Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gays (ATLG; Herek, 1998) scale, a generalized measure of sexual prejudice that includes 20 items (1 = strongly disagree, 9 = strongly agree). We excluded one item that mentioned same-sex marriage. Sample items are “Female homosexuality is an inferior form of sexuality,” “Female homosexuality in itself is no problem, but what society makes of it can be a problem” (reverse coded), “Lesbians are sick,” and “Male homosexuality is a perversion” (α= .94).9

Opposition to same-sex marriage

Participants indicated their endorsement of the following item: “I strongly oppose same-sex marriage” (1 = strongly disagree, 9 = strongly agree).

Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics are provided in Table E of the online supplement. Religiosity was positively correlated with conservatism, r(438) = .349, p < .001, sexual prejudice, r(438) = .449, p < .001, and opposition to same-sex marriage, r(438) = .418, p < .001. Conservatism was positively correlated with sexual prejudice, r(436) = .387, p < .001, and with opposition to same-sex marriage, r(436) = .299, p < .001. Sexual prejudice was positively correlated with opposition to same-sex marriage, r(440) = .814, p < .001.

We hypothesized that the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage would be mediated by political conservatism and sexual prejudice in serial fashion. Therefore, we conducted a serial multiple mediation model, which allows for the simultaneous testing of the indirect effect through both mediators and each mediator by itself (i.e., adjusting for the other mediator). To determine whether such an analysis would be appropriate, we first computed the partial correlation between ideology and sexual prejudice, adjusting for religiosity. This correlation reflects the association between the proposed mediators that remains after accounting for the effects of the independent variable on both (Hayes, 2013). We observed that participants who were more conservative were more prejudiced, even after adjusting for the influence of religiosity on conservatism and sexual prejudice, rM1M2.X(432) = .274, p < .001. Thus, we proceeded to investigate the serial multiple mediation effect (see Table H in the online supplement).

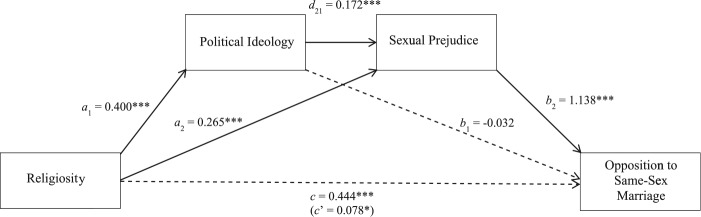

As depicted in Figure 3, we obtained a significant total effect for religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage, c = 0.444, SE = 0.047, p < .001, as well as a significant total indirect effect (i.e., total mediation effect including both mediators), ab = 0.367, SE = 0.045, CI95 = [0.278, 0.456]. To more fully assess the total indirect effect, we examined the contribution for each mediator separately and together in serial fashion. The specific indirect path through political conservatism alone was not significant, a1b1 = −0.013, SE = 0.013, CI95 = [−0.041, 0.012], a1b1cs = −0.012, whereas the specific indirect path through sexual prejudice was, a2b2 = 0.301, SE = 0.047, CI95 = [0.213, 0.395], a2b2cs = 0.282. These findings suggest that only sexual prejudice was an independent mediator of the effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage. As hypothesized, the serial mediation indirect effect path was also significant, a1d21b2 = 0.078, SE = = 0.018, CI95 = [0.049, 0.119], a1d21b2cs = 0.074. This provides support for a multistep serial mediation effect from religiosity → political conservatism → sexual prejudice → opposition to same-sex marriage. Religiosity was also related to opposition to same-sex marriage independent of the effects of political ideology and sexual prejudice (c′ = 0.078, p = .023).10

Figure 3.

Serial multiple mediator model predicting opposition to same-sex marriage from religiosity, political ideology, and sexual prejudice (Study 3).

Note. * p < .05, *** p < .001.

Following up on the nonsignificant indirect effect through ideology, we additionally conducted simple mediation analyses, which confirmed that political conservatism significantly mediated the relationship between religiosity and sexual prejudice, ab = 0.026, SE = 0.008, CI95 = [0.013, 0.043], abcs = 0.054, and that sexual prejudice significantly mediated the relationship between conservatism and opposition to same-sex marriage, ab = 0.249, SE = 0.042, CI95 = [0.173, 0.338], abcs = 0.238. Thus, conservatism did significantly mediate the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage to the extent that it predicted sexual prejudice. Study 3, then, provided evidence for the hypothesis that conservative preferences to maintain the status quo underlie religious opposition to same-sex marriage.

Study 4a

Political conservatism involves two distinct but correlated components, namely, resistance to change and opposition to equality (Jost, 2006; Jost et al., 2003; Jost et al., 2007). Insofar as religious doctrine emphasizes traditional, longstanding mores, as well as values such as compassion and tolerance, we hypothesized that the influence of resistance to change would be greater than the influence of opposition to equality when it comes to same-sex marriage. In Study 4a, we investigated the effects of religiosity, resistance to change, opposition to equality, and sexual prejudice on opposition to same-sex marriage.11

Method

Participants and procedure

In the spring of 2011, 400 heterosexual undergraduates at New York University (Mage = 18.86, SD = 1.05; 288 females) participated in an online mass-testing session in exchange for course credit. In total, 45.1% indicated being Christian, Catholic, or Protestant; 23.9% indicated another religion; 15.1% were atheist; and 15.9% were agnostic. Participants completed a survey that included measures of religiosity, resistance to change, opposition to equality, sexual prejudice, and opposition to same-sex marriage.

Materials

Religiosity

Participants indicated the strength of their religious conviction by responding to the following item on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all religious) to 7 (extremely religious): “How religious are you?”

Resistance to change

Five items tapped the first aspect of conservatism on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree): “I think it’s best to keep society the way it is, even if it has some flaws,” “I think it’s important to protect our society from change,” “I think it’s important to acknowledge the shortcomings of our society” (reverse coded), “It’s better to accept the way things are in order to preserve social order and stability,” and “I think it’s important to develop new ways of doing things in society” (reverse coded; α = .74).

Opposition to equality

Five items taken from Jost and Thompson’s (2000) Economic System Justification Scale measured the second aspect of conservatism on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree): “Social class differences reflect differences in the natural order of things,” “There is no point in trying to make incomes more equal,” “Equal distribution of resources is a possibility for our society” (reverse coded), “Laws of nature are responsible for differences in wealth in society,” and “Economic positions are legitimate reflections of people’s achievements” (α = .61).

Sexual prejudice

We measured sexual prejudice using the same items administered in Study 3 (α = .92).12

Opposition to same-sex marriage

Participants indicated their opinion on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree): “I strongly oppose same-sex marriage.”

Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics are provided in Table G of the online supplement. Religiosity was positively correlated with resistance to change, r(390) = .195, p = .001, opposition to equality, r(395) = .154, p = .002, sexual prejudice, r(394) = .358, p < .001, and opposition to same-sex marriage, r(390) = .339, p < .001. Resistance to change and opposition to equality were positively correlated with sexual prejudice, r(390) = .354, p < .001 and r(396) = .262, p < .001, as well as opposition to same-sex marriage, r(385) = .307, p < .001 and r(391) = .206, p < .001. Sexual prejudice was positively correlated with opposition to same-sex marriage, r(391) = .828, p < .001.

The partial correlation between resistance to change and sexual prejudice remained significant after adjusting for religiosity, prM1M2.X(386) = .312, p < .001, and so did the partial correlation between opposition to equality and sexual prejudice, prM1M2.X(391) = .224, p < .001. These results justified the fitting of serial multiple mediation models.

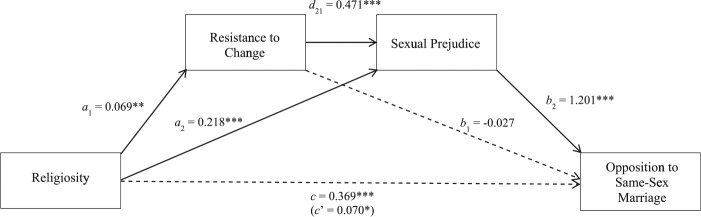

Resistance to change

We first conducted a mediation analysis including resistance to change and sexual prejudice as mediators, adjusting for opposition to equality (see Table H in the online supplement).13 As depicted in Figure 4, we obtained a significant total effect for religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage, c = 0.369, SE = 0.055, p < .001, as well as a significant total indirect effect, ab = 0.300, SE = 0.049, CI95 = [0.205, 0.396]. Examining the contribution for each mediator separately and together in serial fashion, we found that the specific indirect effect through resistance to change alone was not significant, a1b1 = −0.002, SE = 0.007, CI95 = [−0.016, 0.011], a1b1cs = −0.002, whereas the specific indirect effect through sexual prejudice was, a2b2 = 0.262, SE = 0.048, CI95 = [0.172, 0.360], a2b2cs = 0.232. Participants who were more religious were more sexually prejudiced and, in turn, more opposed to same-sex marriage. As hypothesized, the serial mediation indirect effect was also significant, a1d21b2 = 0.039, SE = 0.014, CI95 = [0.016, 0.072], a1d21b2cs = 0.035, revealing that the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage was mediated by resistance to change and sexual prejudice in serial fashion. Religiosity was also related to opposition to same-sex marriage independent of the effects of resistance to change and sexual prejudice (c′ = 0.070, p = .047).14 In sum, then, we find support for sexual prejudice as an independent mediator of the effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage as well as support for a multistep serial mediation effect from religiosity → resistance to change → sexual prejudice → opposition to same-sex marriage.15

Figure 4.

Serial multiple mediator model predicting opposition to same-sex marriage from religiosity, resistance to change, and sexual prejudice, adjusting for opposition to equality (Study 4a).

Note. * p < .05, **p < .01, *** p < .001.

Opposition to equality

We conducted a similar mediation analysis including opposition to equality and sexual prejudice as mediators, this time adjusting for resistance to change.16 We obtained a significant total effect for religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage, c = 0.338, SE = 0.054, p < .001, as well as a significant total indirect effect, ab = 0.269, SE = 0.048, CI95 = [0.180, 0.367]. Examining the contribution for each mediator separately and together in serial fashion, we found that the specific indirect effect through opposition to equality alone was not significant, a1b1 = −0.001, SE = 0.003, CI95 = [−0.009, 0.003], a1b1cs = −0.001, whereas the specific indirect effect through sexual prejudice was, a2b2 = 0.262, SE = 0.048, CI95 = [0.173, 0.361], a2b2cs = 0.236. The serial mediation indirect effect was not significant, a1d21b2 = 0.007, SE = 0.006, CI95 = [−0.001, 0.022], a1d21b2cs = 0.006. Religiosity was related to opposition to same-sex marriage independent of the effect of sexual prejudice (c′ = 0.070, p = .047).17 These results suggest that opposition to equality does not play a unique role in religious opposition to same-sex marriage, either on its own or through sexual prejudice. These results are consistent with our expectation that resistance to change would be a more important factor than opposition to equality when it comes to opposition to same-sex marriage.

Study 4b

Study 4a supported the expectation that conservative preferences to maintain the status quo would help account for relations among religiosity, sexual prejudice, and opposition to same-sex marriage. Especially in light of the number of variables included in the model, we deemed it important to replicate these findings in an independent sample of participants. In this case, however, we employed a measure of opposition to social (rather than economic) equality.

Method

Participants and procedure

In the fall of 2011, 462 heterosexual undergraduates at New York University participated in an online mass-testing session (Mage = 18.86, SD = 1.11; 320 females). One third (33.1%) indicated being Christian, Catholic, or Protestant; another third (33.2%) identified with a different religion; finally, 16.3% were atheist and 17.4% agnostic. Participants completed a survey that included the same measures of resistance to change (α = .80), sexual prejudice (α = .95), and opposition to same-sex marriage as used in Study 4a.18 Religiosity was measured on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all religious) to 11 (extremely religious). We administered a measure of opposition to equality consisting of eight items from the Social Dominance Orientation scale (Pratto et al., 1994; following a factor analysis by Jost & Thompson, 2000). Sample items are “Group equality should be our ideal” and “We would have fewer problems if we treated different groups more equally” (1 = disagree strongly, 11 = agree strongly; reverse scored; α = .88).

Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics are provided in Table L of the online supplement. Religiosity was positively correlated with resistance to change, r(427) = .216, p < .001, sexual prejudice, r(426) = .453, p < .001, and opposition to same-sex marriage, r(426) = .430, p < .001, but it was uncorrelated with opposition to equality, r(427) = .073, p = .131. Resistance to change and opposition to equality were positively correlated with sexual prejudice, r(422) = .440 and r(423) = .342, ps < .001, and opposition to same-sex marriage, r(422) = .336 and r(423) = .285, ps < .001. Sexual prejudice was positively correlated with opposition to same-sex marriage, r(430) = .817, p < .001.

The partial correlation between resistance to change and sexual prejudice remained significant after adjusting for religiosity, prM1M2.X(416) = .391, p < .001, as did the partial correlation between opposition to equality and sexual prejudice, prM1M2.X(417) = .357, p < .001. We therefore proceeded with the fitting of serial multiple mediation models.

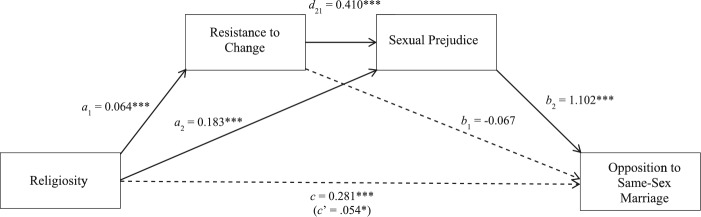

Resistance to change

We first conducted a mediation analysis including resistance to change and sexual prejudice as mediators, adjusting for opposition to equality (see Table M in the online supplement).19 As depicted in Figure 5, we obtained a significant total effect for religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage, c = 0.281, SE = 0.029, p < .001, as well as a significant total indirect effect, ab = 0.226, SE = 0.032, CI95 = [0.165, 0.290]. Examining the contribution for each mediator separately and together in serial fashion, we found that the specific indirect effect through resistance to change alone was not significant, a1b1 = −0.004, SE =0.006, CI95 = [−0.016, 0.006], a1b1cs = −0.007, whereas the specific indirect effect through sexual prejudice was, a2b2 = 0.202, SE = 0.031, CI95 = [0.145, 0.265], a2b2cs = 0.311. Participants who were more religious were more sexually prejudiced and, in turn, more opposed to same-sex marriage. As hypothesized, the serial mediation indirect effect was also significant, a1d21b2 = 0.029, SE = 0.009, CI95 = [0.015, 0.049], a1d21b2cs = 0.044, indicating that the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage was mediated by resistance to change and sexual prejudice in a serial manner. Religiosity was also related to opposition to same-sex marriage independent of the effects of resistance to change and sexual prejudice (c′ = 0.054, p = .014).20 In sum, then, we find support for sexual prejudice as an independent mediator of the effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage as well as support for a multistep serial mediation effect from religiosity → resistance to change → sexual prejudice → opposition to same-sex marriage. These results are consistent with our hypotheses.21

Figure 5.

Serial multiple mediator model predicting opposition to same-sex marriage from religiosity, resistance to change, and sexual prejudice, adjusting for opposition to equality (Study 4b).

Note. * p < .05, *** p < .001.

Opposition to equality

We conducted a similar mediation analysis including opposition to equality and sexual prejudice as mediators, this time adjusting for resistance to change.22 We obtained a significant total effect for religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage, c = 0.250, SE = 0.030, p < .001, as well as a significant total indirect effect, ab = 0.196, SE = 0.031, CI95 = [0.139, 0.259]. Examining the contribution for each mediator separately and together in serial fashion, we found that the specific indirect effect through opposition to equality alone was not significant, a1b1 = −0.001, SE = 0.002, CI95 = [−0.007, 0.001], a1b1cs = −0.001, whereas the specific indirect effect through sexual prejudice was, a2b2 = 0.202, SE = 0.030, CI95 = [0.146, 0.264], a2b2cs = 0.309. The serial mediation indirect effect was not significant, a1d21b2 = −0.005, SE = 0.005, CI95 = [−0.017, 0.004], a1d21b2cs = −0.008. Religiosity was related to opposition to same-sex marriage independent of the effect of sexual prejudice (c′ = 0.054, p = .014).23

Study 4b was a nearly identical replication of Study 4a. Both studies supported our prediction that religious opposition to same-sex marriage would be mediated by political conservatism and sexual prejudice in serial fashion, and that resistance to change would be a more important factor than opposition to equality.

General Discussion

In light of current debates regarding the expansion of gay rights in several countries, including the United States, France, Ireland, Russia, and Australia, this research presents a timely investigation into the motivational underpinnings of religious opposition to same-sex marriage.

In five studies conducted in two countries, we obtained support for a theoretical model in which religious opposition to same-sex marriage is linked to sexual prejudice and conservative preferences to maintain the status quo. This research helps address the question of why people might oppose same-sex marriage at the level of social, personality, and political psychology.

In Study 1, we demonstrated that the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage was mediated by explicit sexual prejudice. In Study 2, we replicated these findings using a measure of behavioral intention, namely willingness to protest against same-sex marriage. These findings support the hypothesis that religious opposition to same-sex marriage is at least partially an expression of sexual prejudice (Herek & McLemore, 2013). In Study 2, we observed that identification with the heterosexual ingroup also predicted willingness to protest against same-sex marriage, but it failed to mediate the relationship between religiosity and willingness to protest. In Study 3, we investigated ideological underpinnings, and observed that the mediating effect of sexual prejudice was linked to conservative ideology. Specifically, we found support for a multistep serial mediation effect from religiosity → political conservatism → sexual prejudice → opposition to same-sex marriage. In Studies 4a and 4b, we more closely examined these processes, and saw that resistance to change was a more important factor than opposition to equality. This suggests that religiosity may foster opposition to same-sex marriage out of a desire to maintain the status quo rather than a desire for inequality per se. Conceptually, this result is compatible with previous work, suggesting that right-wing authoritarianism (akin to resistance to change) was more strongly associated with sexual prejudice than was social dominance orientation (akin to opposition to equality; Haddock et al., 1993; Haslam & Levy, 2006).

There are several important limitations of our work: First, because we set out to examine the motivational underpinnings of religious opposition to same-sex marriage, we treated sexual prejudice, opposition to same-sex marriage, and willingness to protest as distinct psychological constructs. Empirically, however, we observed that they were very highly intercorrelated. In Studies 1, 3, 4a, and 4b, correlations between sexual prejudice and opposition to same-sex marriage ranged from .79 to .83; these correlations are as high as one might expect from two measures of the same psychological construct. Correlations between sexual prejudice and willingness to protest against same-sex marriage were more variable but also high: In Studies 2, 4a, and 4b, they ranged from .57 to .84. Theoretically, we assume that sexual prejudice and opposition to specific policies concerning sexual minorities can be distinguished, but—at an empirical level—it may be difficult to separate these constructs. For this reason, we cannot conclude that sexual prejudice explains opposition to same-sex marriage as an attitudinal variable. In our research, it is unclear whether sexual prejudice produced opposition to same-sex marriage in a downstream fashion, or whether opposition to same-sex marriage was itself a manifestation or component of sexual prejudice. Nevertheless, we believe that whether opposition to same-sex marriage is produced by or is a manifestation of sexual prejudice, their close relationship lends a certain theoretical understanding to that opposition. It is noteworthy that willingness to protest against same-sex marriage was less strongly related to sexual prejudice, and yet we obtained parallel findings for this measure of behavioral intention. Thus, we conclude that opposition to same-sex marriage is strongly related to sexual prejudice, and that sexual prejudice plays a key role in encouraging opposition to same-sex marriage.

Second, for studies in which the independent and mediating variables are not under experimental control, tests of indirect effects are potentially susceptible to bias arising from common causes. For instance, it is possible that a personality variable (such as conscientiousness) simultaneously influenced religiosity, conservatism, and attitudes toward same-sex marriage, and it could therefore provide a further explanation of the effects we observed. In addition, as noted above, our mediation analyses do not provide evidence bearing on the causal ordering of variables. The ordering we proposed is plausible and grounded theoretically in psychological theory and research. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that sexual prejudice motivates the adoption of conservative or religious ideology, and that these variables mediate the effect of sexual prejudice on opposition to same-sex marriage. In all likelihood, some of these relationships are reciprocal. Because of the observational nature of our research, we are unable to draw causal conclusions (Thoemmes, 2015). Despite these limitations, our analyses do suggest that religiosity is associated with opposition to same-sex marriage through conservative ideology and sexual prejudice. It was a genuine empirical possibility that the data would contradict our hypotheses (e.g., that indirect effects would be nonsignificant), but they did not. Future research would do well to adapt experimental methods to investigate the causal effects of making religious or political ideologies salient to observe their impact on attitudes about same-sex marriage.

Although the current research program illuminates clear connections among religiosity, sexual prejudice, and opposition to same-sex marriage, it is important to note that these factors fail to explain all of the statistical variance in such attitudes. Not all religious heterosexuals are sexually prejudiced, and sexual prejudice is not the only reason for opposition to same-sex marriage. A possible explanation has to do with various aspects of political conservatism. People who strongly embrace tradition and conformity—as embodied in religious doctrine—would be expected to oppose same-sex marriage more strongly than those who are drawn to religious messages of compassion and universal love. Attitudes toward same-sex marriage, and gay rights in general, may pose a psychological conflict for those who are intrinsically religious: Should they follow religious teachings or love and accept all human beings?

Given the observed role of resistance to change in explaining opposition to same-sex marriage, legalizing same-sex marriage may bring about increased public support for gay rights over time. Once same-sex marriage is firmly established as the status quo, even those citizens who hold conservative preferences should eventually come to support it (see Jost, Krochik, Gaucher, & Hennes, 2009). Our work—and the theoretical framework that inspired our research—suggests that interventions aimed at reducing antigay prejudice would do well to focus on (a) increasing people’s comfort with deviations from heteronormative romantic arrangements, (b) emphasizing the egalitarian aspect of religion, and (c) undercutting arguments that modern conceptions of marriage have been invariant throughout human history.

In this article, we have focused on same-sex marriage, which is but one issue in the struggle for sexual equality. It is an important issue, insofar as marriage confers unique benefits in many countries, including tangible resources and protections (Herek, 2006). Excluding people from such benefits based on sexual orientation has negative consequences for the mental and physical health of gay men and lesbians (Frost, Lehavot, & Meyer, 2015; Herdt & Kertzer, 2006; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer, 1995; Roderick, McCammon, Long, & Allred, 1998) as well as their interpersonal relationships (Meyer, 2003). Married couples possess constitutional rights that buffer them against stressors associated with severely negative life events—such as the death or incapacitation of a partner—as well as unpleasant situations such as having to testify against a spouse in court, having a noncitizen spouse deported, and having one’s relationship or parental status questioned or challenged (Herek, 2006). For all of these reasons, elucidating the social and psychological processes that shape prejudicial attitudes and behaviors toward gay men and lesbian women is critical for informing theory and practice aimed at enhancing individual and collective well-being as well as the efforts of advocacy groups to promote social justice. Our hope is that the present research program takes a useful step in this direction.

Supplementary Material

All studies reported in this article made use of convenience samples. Sample sizes were determined by the number of students who were enrolled in the various psychology courses and who consented to participate in our research.

We also measured participants’ implicit sexual prejudice and their internal and external motivations to respond without prejudice (Plant & Devine, 1998). Following the advice of reviewers, we summarize the effects of these variables in an online supplement.

Opposition to same-sex marriage was significantly correlated with participant sex and age, and sexual prejudice was correlated with participant sex (see Table A). Nevertheless, adjusting for sex and age did not meaningfully alter the results.

Behavioral intention measures are often considered to be better proxies for real behavior in comparison with attitude measures (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

As in Study 1, we measured participants’ internal and external motivations to respond without prejudice (see online supplement).

The decision to separate group identification and self-categorization was made on the basis of a principal components analysis, which revealed two distinct components. Identification and self-categorization were modestly intercorrelated, r(210) = .35, p < .001.

Participant sex was related to sexual prejudice and willingness to protest against same-sex marriage (see Table C), but adjusting for it did not meaningfully change the results.

We also conducted a study in which system justification motivation was found to mediate the relationship between religiosity and opposition to same-sex marriage. Because sexual prejudice was not measured directly in this study, we have followed the editor’s advice and relegated it to the online supplement.

Because scores on the Attitudes Toward Lesbians (ATL) and Attitudes Toward Gay Men (ATGM) subscales were highly intercorrelated, we used their average in the model. Entering both subscores separately yielded similar results.

Participant sex was significantly related to political ideology, sexual prejudice, and opposition to same-sex marriage (see Table E in online supplement), but adjusting for it did not meaningfully change the results.

We also measured participants’ willingness to protest against same-sex marriage. The findings, which are generally consistent with those obtained for opposition to same-sex marriage, are described in the online supplement.

Entering scores on the ATL and ATGM subscales separately yielded similar results to those reported in the text.

Excluding opposition to equality from the model yielded nearly identical results.

Participant sex was significantly related to religiosity, sexual prejudice, and opposition to same-sex marriage (see Table G in online supplement). When adjusting for it, the direct effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage became nonsignificant (b1 = 0.063, p = .081).

Simple mediation analyses confirmed that resistance to change significantly mediated the relationship between religiosity and sexual prejudice, ab = 0.027, SE = 0.011, CI95 = [0.009, 0.053], abcs = 0.035, and that sexual prejudice significantly mediated the relationship between resistance to change and opposition to same-sex marriage, ab = 0.684, SE = 0.120, CI95 = [0.455, 0.929], abcs = 0.253.

Excluding resistance to change from the analysis rendered the direct effect of religiosity on opposition to equality and the indirect effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage through opposition to equality and sexual prejudice significant, a1 = 0.108, SE =0.034, p = .002 and a1d21b2 = 0.030, SE = 0.012, CI95 = [0.012, 0.058], a1d21b2cs = 0.027. This finding suggests that opposition to equality plays a role to the extent that it overlaps with resistance to change.

Adjusting for participant sex rendered the direct effect of religiosity on opposition to same-sex marriage nonsignificant (b1 = 0.063, p = .081).

We again measured participants’ willingness to protest against same-sex marriage and obtained generally consistent findings (see online supplement).

Omitting opposition to equality from the model yielded nearly identical results.

Participant sex was significantly related to opposition to equality, sexual prejudice, and opposition to same-sex marriage (see Table J in online supplement), but adjusting for it yielded nearly identical results.

Simple mediation analyses furthermore confirmed that resistance to change significantly mediated the relationship between religiosity and sexual prejudice, ab = 0.019, SE = 0.007, CI95 = [0.008, 0.036], abcs = 0.043, and that sexual prejudice significantly mediated the relationship between resistance to change and opposition to same-sex marriage, ab = 0.608, SE = 0.108, CI95 = [0.410, 0.830], abcs = 0.254.

Omitting resistance to change from the model yielded nearly identical results.

Adjusting for participant sex yielded nearly identical results.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) declared receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported in part by Canada Graduate Scholarships received from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council by the third and fifth author.

Supplemental Material: Supplementary material is available online with this article.

References

- Altemeyer B. (1988). Enemies of freedom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Babst G. A., Gill E. R., Pierceson J. (Eds.). (2009). Moral argument, religion, and same-sex marriage: Advancing the public good. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict XVI (2012). Address of His Holiness Benedict XVI on the occasion of Christmas greetings to the Roman Curia. Retrieved from http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2012/december/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20121221_auguri-curia.html.

- Barth J., Parry J. (2009). Political culture, public opinion, and policy (non)diffusion: The case of gay- and lesbian-related issues in Arkansas. Social Science Quarterly, 90, 309-325. [Google Scholar]

- Blenner J. A. (2015). Sexual minority stigma and system justification theory: How changing the status quo impacts marriage and housing equality (Theses, dissertations, and student research: Department of Psychology, Paper 81). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/psychdiss/81

- Fiedler K., Schott M., Meiser T. (2011). What mediation analysis can (not) do. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1231-1236. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M., Ajzen I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Frost D. M., Lehavot K., Meyer I. H. (2015). Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38, 1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock G., Zanna M. P., Esses V. M. (1993). Assessing the structure of prejudicial attitudes: The case of attitudes toward homosexuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1105-1118. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N., Levy S. R. (2006). Essentialist beliefs about homosexuality: Structure and implications for prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 471-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G., Kertzer R. (2006). I do but I can’t: The impact of marriage denial on the mental health and sexual citizenship of lesbians and gay men in the United States. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 3, 33-49. [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. M. (1994). Assessing heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A review of empirical research with the ATLG scale. In Greene B., Herek G. M. (Eds.), Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 206-228). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. M. (1998). The Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men (ATLG) Scale. In Davis C. M., Yarber W. H., Bauserman R., Schreer G., Davis S. L. (Eds.), Sexuality-related measures: A compendium (pp. 392-394). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. M. (2000). The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 19-22. [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. M. (2006). Legal recognition of same-sex relationships in the United States: A social science perspective. American Psychologist, 61, 607-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. M. (2011). Anti-equality marriage amendments and sexual stigma. Journal of Social Issues, 67, 413-426. [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. M., McLemore K. A. (2013). Sexual prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. (2015, April 8). Three takeaways from Indiana religious freedom law frenzy. Washington Blade. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonblade.com/2015/04/08/three-takeaways-from-indiana-religious-freedom-law-frenzy/

- Jones J. M. (2010, May 24). Americans’ opposition to gay marriage eases slightly. Gallup Poll. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/128291/americans-opposition-gay-marriage-eases-slightly.aspx

- Jost J. T. (2006). The end of the end of ideology. American Psychologist, 61, 651-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., Banaji M. R. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 1-27. [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., Glaser J., Kruglanski A. W., Sulloway F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., Hawkins C. B., Nosek B. A., Hennes E. P., Stern C., Gosling S. D., Graham J. (2014). Belief in a just god (and a just society): A system justification perspective on religious ideology. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 34, 56-81. [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., Krochik M., Gaucher D., Hennes E. P. (2009). Can a psychological theory of ideological differences explain contextual variability in the contents of political attitudes? Psychological Inquiry, 20, 183-188. [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., Langer M., Badaan V., Azevedo F., Etchezahar E., Ungaretti J., Hennes E. (in press). Ideology and the limits of self-interest: System justification motivation and conservative advantages in mass politics. Translational Issues in Psychological Science. [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., Nam H. H., Amodio D. A., Van Bavel J. J. (2014). Political neuroscience: The beginning of a beautiful friendship. Advances in Political Psychology, 35, 3-42. [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., Napier J. L., Thorisdottir H., Gosling S. D., Palfai T. P., Ostafin B. (2007). Are needs to manage uncertainty and threat associated with political conservatism or ideological extremity? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 989-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., Thompson E. P. (2000). Group-based dominance and opposition to equality as independent predictors of self-esteem, ethnocentrism, and social policy attitudes among African Americans and European Americans. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 209-232. [Google Scholar]

- Jost J. T., van der Toorn J. (2012). System justification theory. In van Lange P. A. M., Kruglanski A. W., Higgins E. T. (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 313-343). London, England: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Katz C. (2011, June 24). CPSNY Chair Mike Long: Gay marriage will pass. NY Daily News. Retrieved from http://www.nydailynews.com/blogs/dailypolitics/cpsny-chair-mike-long-gay-marriage-pass-updated-blog-entry-1.1685482

- Luguri J. B., Napier J. L., Dovidio J. F. (2012). Reconstruing intolerance: Abstract thinking reduces conservatives’ prejudice against non-normative groups. Psychological Science, 23, 756-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx G. T. (1967). Religion: Opiate or inspiration of civil rights militancy among Negroes? American Sociological Review, 32, 64-72. [Google Scholar]

- Mays V. M., Cochran S. D. (2001). Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1869-1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J. (2014, May 21). Same-sex marriage support reaches new high at 55%. Gallup Poll. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/169640/sex-marriage-support-reaches-new-high.aspx

- Meyer I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 7, 9-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport F. (2011, May 20). For first time, majority of Americans favor legal gay marriage. Gallup Poll. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/147662/First-Time-Majority-Americans-Favor-Legal-Gay-Marriage.aspx

- Newport F. (2012, December 5). Religion big factor for American against same-sex marriage. Gallup Poll. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/159089/religion-major-factor-americans-opposed-sex-marriage.aspx

- Obergefell v. Hodges, U. S. (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Olson L., Cadge W., Harrison J. (2006). Religion and public opinion about same-sex marriage. Social Science Quarterly, 87, 340-360. [Google Scholar]

- Pacilli M. G., Taurino A., Jost J. T., van der Toorn J. (2011). System justification, right-wing conservatism, and internalized homophobia: Gay and lesbian attitudes toward same-sex parenting in Italy. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 65, 580-595. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. (2003, July 24). Religion and politics: Contention and consensus. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/2003/07/24/religion-and-politics-contention-and-consensus/

- Plant E. A., Devine P. G. (1998). Internal and exernal motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 811-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popham P. (2005, November 30). Pope restates ban on gay priests and says homosexuality is “disordered.” Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/pope-restates-ban-on-gay-priests-and-says-homosexuality-is-disordered-517522.html

- Poteat V. P., Espelage D. L., Green H. D., Jr. (2007). The socialization of dominance: Peer group contextual effects on homophobic and dominance attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 1040-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratto F., Sidanius J., Stallworth L. M., Malle B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741-763. [Google Scholar]

- Roderick T., McCammon S. L., Long T. E., Allred L. J. (1998). Behavioral aspects of homonegativity. Journal of Homosexuality, 36, 79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat D. E., Powell-Williams M., Maddox G., de Vries K. M. (2011). Religion, politics, and support for same-sex marriage in the United States, 1988-2008. Social Science Research, 40, 167-180. [Google Scholar]

- Swank E., Raiz L. (2010). Predicting the support of same-sex relationship rights among social work students. Journal of Gay Lesbian Social Services, 22, 149-164. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H., Turner J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In Worchel S., Austin W. G. (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7-24). Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Thoemmes F. (2015). Reversing arrows in mediation models does not distinguish plausible models. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37, 226-234. [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. C. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Waters E., Jindasurat C., Wolfe C. (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and HIV-affected hate violence in 2015. New York, NY: National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead A. L. (2010). Sacred rites and civil rights: Religion’s effect on attitudes toward same-sex unions and the perceived cause of homosexuality. Social Science Quarterly, 91, 63-79. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley B. B., Jr. (1999). Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 126-134. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedermann W., von Eye A. (2015). Direction of effects in mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 20, 221-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfield N. (2010, May 13). Pope decries abortion, same-sex marriage at Fatima. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/huff-wires/20100513/eu-pope-portugal

- Wofford T. (2014, October 14). What did the Vatican really say about gay marriage yesterday? Catholics disagree. Newsweek. Retrieved from http://www.newsweek.com/what-did-vatican-really-say-about-gay-marriage-yesterday-catholics-disagree-277360

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.