Abstract

Three patients with giant cell tumour of bone (GCTB) in the lower extremity, where the only surgical treatment options were amputation or severe weakening of the bone, were treated with denosumab (D-mab) to strengthen the bone mass in the tumour. In order to quantify changes in bone mineral density (BMD) in the GCTB lesion during D-mab treatment, we did repeated dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans. The patients underwent operation after 3, 4 and 8 months of D-mab treatment, respectively. The tumours in all three patients responded markedly to D-mab, and up to 50% BMD increase was observed. There was almost no BMD change in the control scans in the hip and spine of the same patients. DXA scans provide no information about local tumour response, but may be of value in evaluation of the time and size of the D-mab response in GCTB, and thereby aid in finding the best timing for surgery.

Keywords: Musculoskeletal And Joint Disorders, Drug Therapy Related To Surgery, Orthopaedics, Cancer, Orthopaedic And Trauma Surgery

Background

A giant cell tumour of bone (GCTB) is considered a borderline malignant tumour (slow development, local destruction), but approximately 2% of the tumours are malignant and metastasize—most often to the lungs. Most GCTBs are located at the epiphysis of the long bones next to the joints, where they form lytic lesions. The most common anatomical locations include the knee, hip, shoulder, wrist and lower back. GCTBs are quite rare (1–2:1 000 000 per year) but typically occur in young adults (ages 20–50), and more commonly in women.1 2

A GCTB is heterogeneous and composed of multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells and mononuclear stromal cells. The multinucleated giant cell contains 50–100 nuclei, and has a characteristic appearance under the microscope as several cells fuse to form ‘giant cells’. For long, it has been known that the giant cells are not the neoplastic component. The elongated, mononuclear stromal cells account for the imbalance in RANKL expression, which causes the osteoclast to differentiate into giant cells.3

The recommended treatment regime is surgery, if possible with curettage of the pathological tissue and subsequent filling of the cavity with cement or bone graft. Alternatively wide resection or even amputation. Radiation therapy and pharmacotherapy with bisphosphonates have been tried when surgery was not possible due to risk of physical impairment (instead of amputation). Unfortunately, radiation therapy has the potential to induce malignancy, and bisphosphonates have not been sufficiently effective. Local recurrence rate is between 20% and 50%, depending on the type of surgery performed.4 5

Recently, denosumab (D-mab) has been introduced in the treatment of GCTB. D-mab is a human monoclonal antibody, administered by subcutaneous injection, which blocks RANKL in the RANKL/RANK/OPG pathway and inhibits the maturation of osteoclasts and thereby reduces the bone reabsorption mediated by the osteoclasts. In phase 2 studies, D-mab has proven effective (i.e. radiologic tumour reduction, microscopically fewer giant cells and subjective pain relief) in treatment of GCTBs by inhibiting osteoclastic bone reabsorption, but the follow-up regime is still in the developing phase.4 6

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan measures the bone mineral density (BMD) and may be used to quantify bone mass. To our knowledge, DXA scans have not previously been used as an efficacy measure in D-mab treatment of GCTB. In this case, we followed three patients with GCTBs by DXA scans to quantify changes in BMD in the GCTB lesion during D-mab treatment.

Case presentation

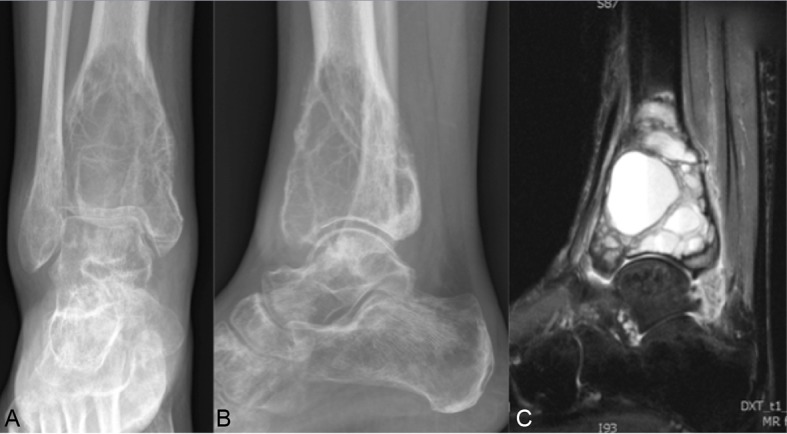

Case 1: GCTB in the distal tibia

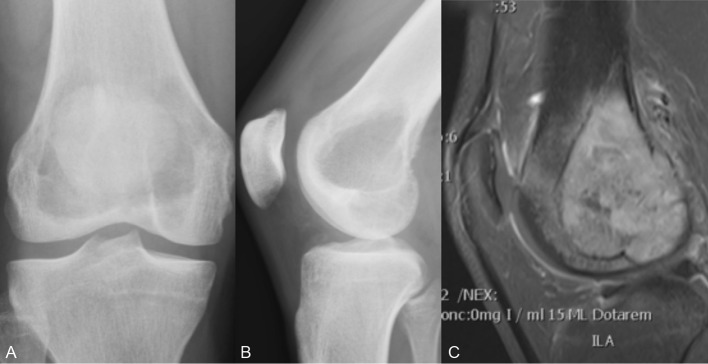

A 30-year-old woman had suffered 9 months of increasing pain and swelling of the ankle. She was diagnosed with a GCTB in the epiphysis of the right distal tibia on X-ray and subsequent MRI scans (figure 1A–C). Previously, she was in good health and with no chronic or known hereditary disease.

Figure 1.

Case 1: (A) Anteroposterior (AP) X-ray of the tumour. (B) Lateral X-ray of the tumour. (C) MRI of the tumour.

The tumour was considered operable only by lower leg amputation surgery (because of the tumour size and location very close to the ankle joint). In order to downstage the tumour prior to possible limb salving surgery, the patient was offered D-mab treatment 120 mg at days 1, 8 and 15 and eventually every 4 weeks. Within a week after D-mab was initiated, the patient experienced pain relief which continued during the D-mab treatment. MRI scans after 1 and 4 months of treatment showed increased calcification and regression of the tumour. After 8 months, MRI scan showed further calcification, but no change in tumour size. For X-ray, see figure 2A,B. For that reason, D-mab treatment was stopped and surgery with curettage of the tumour, autogen bone transplantation from the iliac crest and cementation was conducted (figure 3A,B). The bone quality during surgery was described as very hard. Four months postoperatively, the pain in the ankle returned and caused walking disabilities. After 6 months, plain radiographs revealed signs of local tumour recurrence. There was no sign of extraosseous tumour extent. Again, the patient was offered D-mab treatment, expectedly lifelong. Meanwhile, the patient had a wish for pregnancy, and therefore D-mab treatment was contraindicated. The patient and physicians agreed on lower leg amputation surgery and preparation of leg prosthesis. This was conducted 7 months after the primary tumour surgery, and as expected, histology of the tumour again showed GCTB. Three years following the lower leg amputation, the patient has not had any relapse of GCTB and has carried out a healthy pregnancy.

Figure 2.

Case 1 after 8 months of denosumab (D-mab) treatment. (A) Anteroposterior (AP) X-ray. (B) Lateral X-ray.

Figure 3.

Case 1 after primary surgery. (A) Anteroposterior (AP) X-ray. (B) Lateral X-ray.

Case 2: GCTB in the distal femur

A 23-year-old male student had suffered from increasing unilateral knee pain and sensation of knee instability for half a year. With suspected rupture of anterior cruciate ligament, an MRI was performed. It showed a tumour in the right distal femur filling most of the femoral condyle (figure 4A–C). Histology after bone biopsy concluded GCTB. The tumour almost had connection to the osteochondral transition of the knee joint, which meant a high risk of physical impairment if curettage was performed. For that reason, the patient was offered D-mab, with the same dose regimen as in case 1 in effort to improve the chances for a successful joint preserving operation. The patient received 3 months of D-mab treatment. MRI scan then revealed increased bone mineralisation and surgery with curettage and cementation was done (figure 5A,B). As in case 1, the bone quality was reported as being very hard. One year postoperatively, the patient still had activity-based knee pain, but no sign of relapse. One and a half year postoperatively, he resumed running. After 3 years, plain radiograph still shows no signs of relapse.

Figure 4.

Case 2: (A) Anteroposterior (AP) X-ray of the tumour. (B) Lateral X-ray of the tumour. (C) MRI of the tumour.

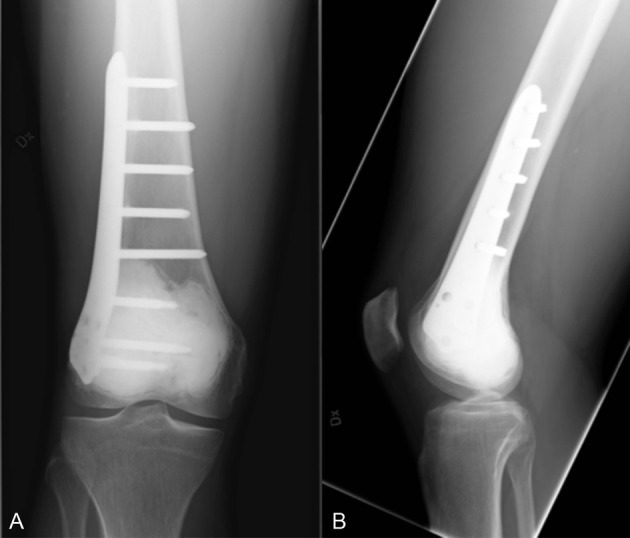

Figure 5.

Case 2 after surgery. (A) Anteroposterior (AP) X-ray. (B) Lateral X-ray.

Case 3: GCTB in the proximal femur

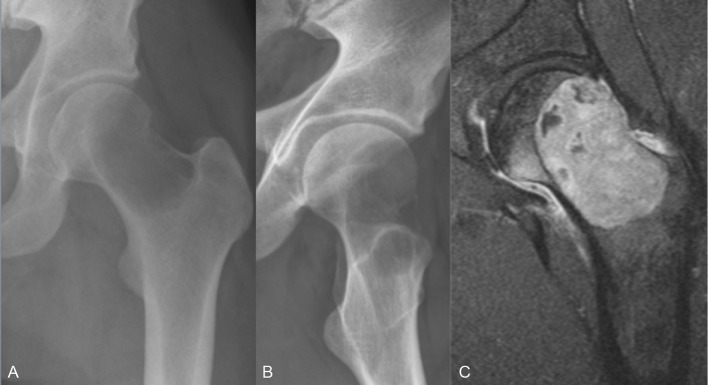

A 28-year-old man had complained of groin pain for several years. He was a student and played soccer at high level. Because of pain progression, a plain radiograph was conducted. It revealed a cystic demineralised tumour in the femoral neck, and which on MRI showed a breakthrough of the cortical bone (figure 6A–C). Traditional surgery would mean high risk of physical impairment. To downstage the tumour and optimise the conditions for a successful surgery, the patient was offered D-mab with the same dose regimen as in patients 1 and 2. Three months later, bone mineralisation was clearly improved on MRI and radiography (figure 7A,B), and the patient was scheduled for surgery. Curettage, bone transplantation and stabilisation with a dynamic hip screw were done successfully (figure 8A,B). Three years later, there were no subjective or radiographic signs of recurrence. The patient has resumed an active lifestyle, and plays soccer at high level.

Figure 6.

Case 3: (A) Anteroposterior (AP) X-ray of the tumour. (B) Lateral X-ray of the tumour. (C) MRI of the tumour.

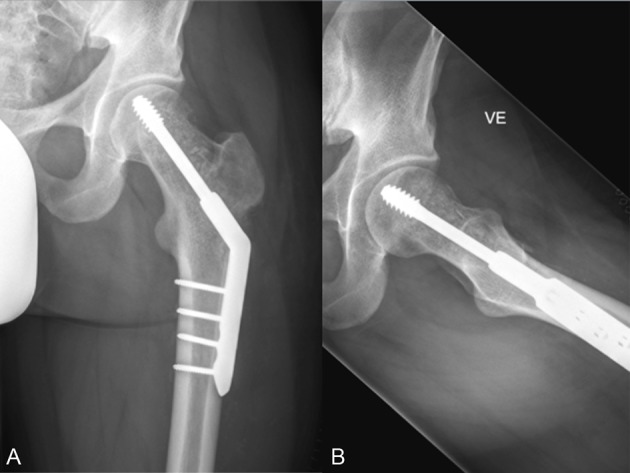

Figure 7.

Case 3 after 3 months of denosumab (D-mab) treatment. (A) Anteroposterior (AP) X-ray. (B) Lateral X-ray.

Figure 8.

Case 3 after surgery. (A) Anteroposterior (AP) X-ray. (B) Lateral X-ray.

Investigations

Efficacy of D-mab treatment was evaluated by conventional radiography and MRI scans, but as a trial also longitudinal DXA scans were performed to evaluate changes in BMD of the GCTB during treatment.

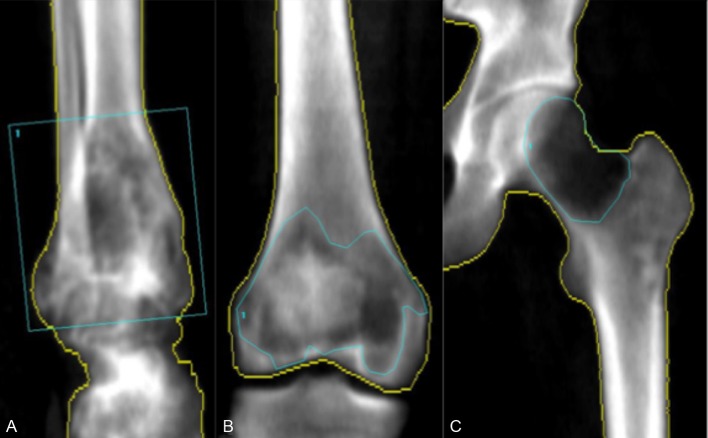

The DXA scanner (iDXA, GE Healthcare) had a predetermined scan mode for the hip region (case 3). For the ankle (case 1) and knee (case 2), we used rice bags as tissue equivalent material. enCORE V.14 (GE Healthcare) was used to analyse the DXA data (figure 9A,B). The program identified the borders of the bone. These were manually corrected when needed, which was the case in the most lytic areas of the bone. The extent of the tumour was marked manually on the first scan (region of interest = ROI). The ROI and bone borders from the first scan was used as a template and copied to the successive scans, to make sure the same area of bone was evaluated (cases 2 and 3). The borders of the tumour in the distal tibia (case 1) were not well defined and almost included the whole distal tibia. For that reason, the tumour was not marked with an outline, but instead a box was placed around the tumour area. Therefore, a bit of non-tumour-affected bone was included in this case but it was similar at all follow-ups. An ordinary DXA scan (spine and femoral neck/hip) to assess osteoporosis (T-score) and a reference BMD status was conducted at baseline and follow-up evaluations.

Figure 9.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan image and marking of the region of interest. (A) Case 1. (B) Case 2. (C) Case 3.

Outcome and follow-up

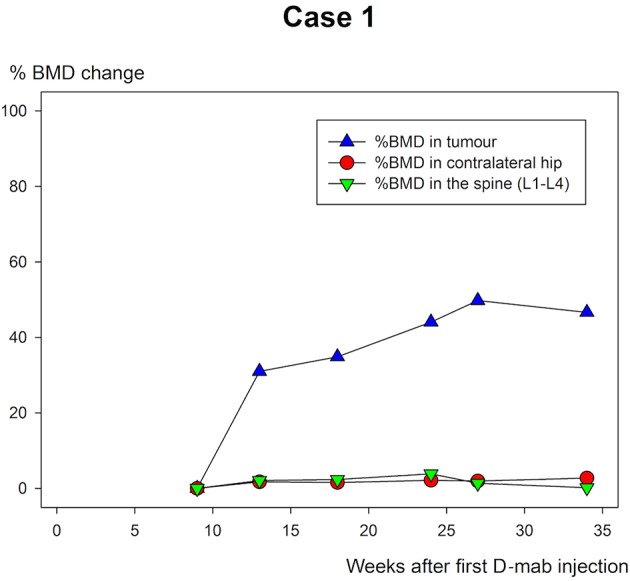

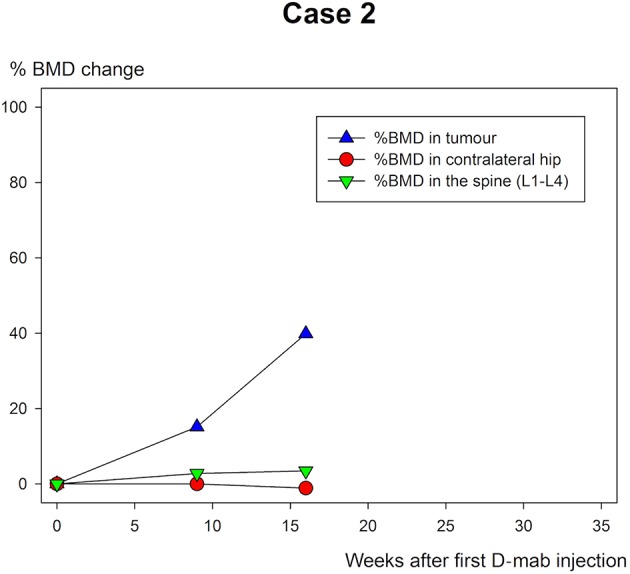

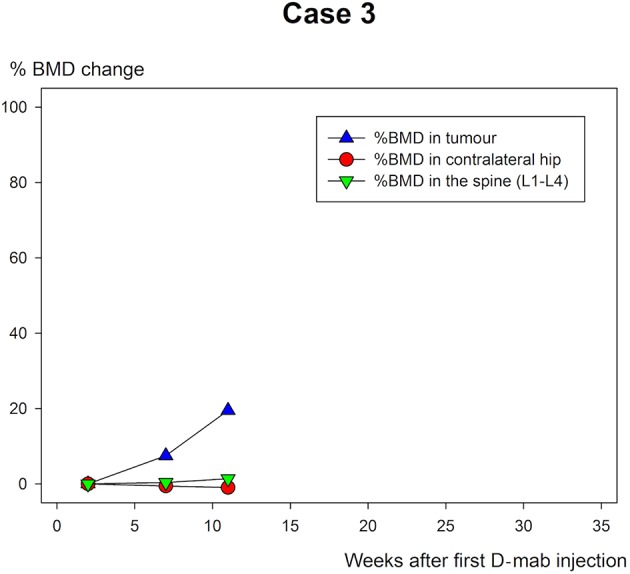

The BMD measurements are shown in table 1 and figure 10–12. All three cases showed extensive increase in BMD in the tumour-affected area with 46.6% (case 1), 39.8% (case 2) and 19.5% (case 3) until the time of surgery.

Table 1.

BMD change in weeks after the first denosumab injection

| Weeks after first denosumab injection | BMD of the tumour (g/cm2) | % Increase | BMD of the femoral neck contralateral of tumour side (g/cm2) | T-score | % Increase | BMD of the spine (g/cm2) | T-score | % Increase |

| Case 1 | ||||||||

| 9 | 0.729 | 0 | 0.951 | −0.4 | 0 | 1.074 | −0.9 | 0 |

| 13 | 0.955 | 31.0 | 0.968 | −0.3 | 1.8 | 1.097 | −0.7 | 2.1 |

| 18 | 0.983 | 34.8 | 0.966 | −0.3 | 1.6 | 1.100 | −0.7 | 2.4 |

| 24 | 1.050 | 44.0 | 0.972 | −0.3 | 2.2 | 1.117 | −0.5 | 3.8 |

| 27 | 1.092 | 49.8 | 0.970 | −0.3 | 2.0 | 1.089 | −0.8 | 1.4 |

| 34 | 1.069 | 46.6 | 0.978 | −0.2 | 2.8 | 1.076 | −0.9 | 0.2 |

| Case 2 | ||||||||

| 0 | 0.793 | 0 | 1.187 | 0.6 | 0 | 1.288 | 0.6 | 0 |

| 9 | 0.913 | 15.1 | 1.187 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.325 | 0.9 | 2.8 |

| 16 | 1.109 | 39.8 | 1.174 | 0.5 | −1.1 | 1.334 | 1.0 | 3.4 |

| Case 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 0.574 | 0 | 1.275 | 1.2 | 0 | 1.489 | 2.2 | 0 |

| 7 | 0.617 | 7.5 | 1.268 | 1.2 | −0.6 | 1.495 | 2.3 | 0.4 |

| 11 | 0.686 | 19.5 | 1.263 | 1.1 | −1.0 | 1.510 | 2.4 | 1.4 |

BMD, bone mineral density.

Figure 10.

Case 1: % bone mineral density (BMD) change of the ankle in weeks after first denosumab (D-mab) injection.

Figure 11.

Case 2: % bone mineral density (BMD) change of the femoral condyles of the knee in weeks after the first Denosumab (D-mab) injection.

Figure 12.

Case 3: % bone mineral density (BMD) change of the femoral neck tumour area in weeks after the first denosumab (D-mab) injection.

Patient 1 was followed for a longer period than the other two and continued to increase BMD in the tumour area until last follow-up (figure 5–7). All the ordinary control DXA scans showed no chance in BMD of relevance.

Discussion

In this case study, all three patients with primary inoperable GCTBs experienced both subjective pain relief and objective improvement in terms of BMD increase at the tumour site during D-mab treatment. Patients 2 and 3 had curatively intended limb preserving surgery 3 and 4 months following their diagnosis. There were no signs of recurrence or physical impairment 3 years after surgery. Patient 1 had a more complicated tumour in the ankle region and sustained limp conserving surgery 8 months after initiation of D-mab treatment. Thereafter, D-mab treatment was terminated, the GCTB recurred and the patient chose lower leg amputation.

Müller et al have focused on benefits and risks of D-mab treatment of GCTB.7 A total of 18 patients were treated with D-mab preoperatively. They reported no increased risk of recurrence, but argued for the need of a local adjuvant intraoperatively, due to latent tumour cells imbedded in the newly formed bone. Surgically, they reported less bleeding and the peripheral rim was easier to reconstruct. In our three cases, there was no intraoperative medical adjuvant, only the heat generated during cement hardening.

All three patients had increasing BMD in the GCTB region throughout D-mab treatment and thus effective blocking of the osteoclastic tumour cells.

This indicates that DXA scanning in the tumour area could be of value as an early marker of an effective tumour response to D-mab treatment of GCTB. A study with weekly DXA scans would be needed to identify the optimal timing for DXA rescans.

While the BMD increased markedly in the tumour area of all three patients during D-mab treatment, there was almost no BMD change in the normal bone (spine/hip). Thus, DXA scanning may be of value in evaluation of the time and size of the D-mab response. With longer follow-up and identification of an expected ‘upper limit’ for BMD improvement during D-mab treatment, DXA scans may in the future also have a place in timing surgery to the point when the tumour is most blocked and the bone at the tumour site is the most mineralised.

Since DXA scans would not provide strong information about local tumour growth, regular radiographs and MRI would still be needed in evaluation of tumour progression and treatment response (size).

In the future, DXA scans might also prove valuable in evaluation of the dose–response for D-mab treatment of GCTBs. Further research in this area will be needed.

Learning points.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanning (measurement of bone mineral density) may be of value in evaluation of the time and size of the denosumab response treatment of giant cell tumour of bone (GCTB).

DXA scanning can be of help in deciding the best timing for surgery after initiation of denosumab treatment of GCTB.

DXA scan can be relevant in finding the maximal tumour response to denosumab.

Denosumab treatment can increase the chances of successful surgical removal of GCTB without physical impairment.

Footnotes

Contributors: PHJ, IKM and MS set up the treatment and follow-up regime. IKM completed the DXA scans. CV and MS analysed the data. CV wrote the article, and MS, PHJ and IKM revised the article. All four authors approved the final version and agreed to be accountable for the article and have ensured that all questions regarding the accuracy or integrity of the article are investigated and resolved.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Raskin KA, Schwab JH, Mankin HJ, et al. Giant cell tumor of bone. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013;21:118–26. 10.5435/JAAOS-21-02-118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobti A, Agrawal P, Agarwala S, et al. Giant cell tumor of bone - an overview. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2016;4:2–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dufresne A, Derbel O, Cassier P, et al. Giant-cell tumor of bone, anti-RANKL therapy. Bonekey Rep 2012;1:149 10.1038/bonekey.2012.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh AS, Chawla NS, Chawla SP. Giant-cell tumor of bone: treatment options and role of denosumab. Biologics 2015;9:69–74. 10.2147/BTT.S57359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kivioja AH, Blomqvist C, Hietaniemi K, et al. Cement is recommended in intralesional surgery of giant cell tumors: a scandinavian sarcoma group study of 294 patients followed for a median time of 5 years. Acta Orthop 2008;79:86–93. 10.1080/17453670710014815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaston CL, Grimer RJ, Parry M, et al. Current status and unanswered questions on the use of denosumab in giant cell tumor of bone. Clin Sarcoma Res 2016;6 10.1186/s13569-016-0056-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller DA, Beltrami G, Scoccianti G, et al. Risks and benefits of combining denosumab and surgery in giant cell tumor of bone-a case series. World J Surg Oncol 2016;14:281 10.1186/s12957-016-1034-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]