Abstract

Objectives

Addressing the social determinants of health has been identified as crucial to reducing health inequities. However, few evidence-based interventions exist. This study emerges from an ongoing collaboration between physicians, researchers and a financial literacy organisation. Our study will answer the following: Is an online tool that improves access to financial benefits feasible and acceptable? Can such a tool be integrated into clinical workflow? What are patient perspectives on the tool and what is the short-term impact on access to benefits?

Methods

An advisory group made up of patients living on low incomes and representatives from community agencies supports this study. We will recruit three primary care sites in Toronto, Ontario and three in Winnipeg, Manitoba that serve low-income communities. We will introduce clinicians to screening for poverty and how benefits can increase income. Health providers will be encouraged to use the tool with any patient seen. The health provider and patient will complete the online tool together, generating a tailored list of benefits and resources to assist with obtaining these benefits. A brief survey on this experience will be administered to patients after they complete the tool, as well as a request to contact them in 1 month. Those who agree to be contacted will be interviewed on whether the intervention improved access to financial benefits. We will also administer an online survey to providers and conduct focus groups at each site.

Ethics and dissemination

Key ethical concerns include that patients may feel discomfort when being asked about their financial situation, may feel obliged to complete the tool and may have their expectations falsely raised about receiving benefits. Providers will be trained to address each of these concerns. We will share our findings with providers and policy-makers interested in addressing the social determinants of health within healthcare settings.

Trial registration number

Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02959866. Registered 7 November 2016. Retrospectively registered. Pre-results.

Keywords: cial determinants of health, income, poverty, primary care, health promotion

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Multisite study involving clinics in two provinces.

Pragmatic implementation of a novel tool in the real world of busy primary care clinics.

Mixed-methods evaluation, using several data sources to triangulate findings.

Convenience sampling method for patients.

A short follow-up period (4 weeks after intervention) may underestimate the impact of the novel tool.

Background

The WHO defines the social determinants of health (SDOH) as ‘the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age’, and include the material resources a person has available that are necessary to live a healthy life.1 SDOH have been identified as a key reason for health inequities between different individuals and groups within a population and help explain differences in access to health services.2 The WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, the British Medical Association and the Canadian Medical Association have all called on the health sector to play a greater role in addressing the SDOH through implementing and evaluating new interventions and serving as a link between disadvantaged communities and social and community services.3–6 Primary care settings in particular are uniquely opportune spaces to take action.7 Primary care providers follow patients longitudinally are community based and often have knowledge of the broader familial and social contexts that shape health and disease.8

One of the most important SDOH is income security: a person’s actual, perceived and expected income.9 10 Income influences the presence and severity of most health conditions. People living in poverty may have difficulty paying rent,11 affording nutritious food,12–15 affording transportation and engaging with others socially.6–9 Many studies have shown that economically marginalised people tend to live shorter lives, experience a greater burden of disease and disability and rate their health status as worse than the wealthy.16–21 One aspect of income security is access to financial benefits.

There are currently few, rigorously evaluated SDOH interventions deployed in clinical settings that have been found to improve material conditions and subsequently the health of individuals and families.22 23 Welfare benefits advice services within general practices in the UK have been found to increase the income of recipients, although improvements in health were not assessed in most studies.24 Similarly, a health promotion service in Toronto, Canada has been developed to assist patients with income security within primary care settings, but the impact has not yet been reported.25 Several studies in the USA have demonstrated the effectiveness of clinic-based interventions at connecting patients to community resources to address SDOH. In Boston, the Well-child Care Visit, Evaluation, Community Resources, Advocacy, Referral, Education study took place in paediatric clinics.26 A waiting room survey screened for social needs and members of the healthcare team provided information on community resources, adding less than 2 min to the visit. At 1 month, 20% of the intervention group parents reported contacting a referred community resource versus 2.2% of parents in the control group.27 The online tool, HelpSteps,28 29 screens for a much larger number of social needs, taking on average 25 min to complete, with 90% of users identifying at least one social need and 96% reporting they would recommend its use to a friend or peer.30 The California iScreen study,31 also tested in paediatric clinics, used the Health Leads32 model and found that social needs can be identified and providing patient supports led to improvements in parent-reported child health.33 In Canada, a paper-based clinical tool has helped train physicians and other health providers to consider poverty as a health issue.34 This tool has been adapted by the College of Family Physicians of Canada for use in all provinces and territories. No studies to date have evaluated the impact of this tool on providers or patients.

Our study focuses on developing, implementing and evaluating an online tool in primary care settings that focuses on access to financial benefits. This study emerges from an ongoing collaboration between family physicians, researchers and a charitable financial literacy organisation, Prosper Canada.35 This paper describes the protocol for this mixed-methods study that will evaluate the implementation and impact of this online tool. Our study will assess: (1) whether health providers find using a tool to address access to financial benefits in a clinical setting feasible and acceptable; (2) lessons learned and opportunities identified to integrate the tool within the regular workflow of primary healthcare organisations and (3) feedback from patients using the online tool and the short-term impacts on awareness and access to benefits.

Methods/design

This study will use qualitative and quantitative methods to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of using an online tool in primary care to address access to financial benefits. The online income tool will be implemented at six primary care clinics, three in Toronto, Ontario and three in Winnipeg, Manitoba. All sites serve large numbers of patients with complex health needs and low socioeconomic status (table 1).

Table 1.

Clinic characteristics for six primary care sites in Ontario and Manitoba

| Clinic type | Location | Patient population | Provider(s) who will predominantly administer the tool | Method of recruiting patients |

| Family health team | Toronto, Ontario | Over 30% of patients live in neighbourhoods that have average incomes in the lowest quintile. | Family physicians and nurse practitioner | Reception staff provide patients an information sheet or healthcare providers initiate enrolment |

| Community health centre | Toronto, Ontario | Priority populations include newcomers and patients with substance use or mental health needs. | Family physician, nurse practitioners and social workers | Healthcare provider initiated |

| Family health team | Toronto, Ontario | Serves wide range of patients with a focus on the unattached, medically and/or socially complex, high-need patients | Family physicians and patient navigator | Healthcare provider initiated |

| Community health centre | Winnipeg, Manitoba | Serves one of the most impoverished areas in the city. The neighbourhood has an unemployment rate of 17% with 34% of the families living in poverty. There are 83% female lone-parent families and 16.9% of the community are members of a visible minority group with another 29% of indigenous ancestry. | Family physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers, support workers | Healthcare provider initiated |

| Community health centre | Winnipeg, Manitoba | Serves a diverse inner city community providing a very wide range of services to individuals, families, teens, adults and geriatrics within our geographic community. Special focus for priority populations of marginalised groups such as immigrants and refugees, transgendered individuals and those living with sexually transmitted infections. | Family physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers, support workers, counsellors | Healthcare provider initiated |

| Community health centre | Winnipeg, Manitoba | Serves a generally low-income north Winnipeg neighbourhood. Focus on patients within the catchment area with particular interest in chronic disease care. | Family physicians, nurse practitioner, nurses | Healthcare provider initiated |

Intervention

The intervention is centred on an online tool that guides users through 12 demographic and income-related questions and subsequently generates a customised list of relevant provincial and federal government benefits and tax credits. The initial screening question ‘Do you ever have difficulty making ends meet at the end of the month?’ has been validated in similar settings to identify patients who live below the Canadian poverty line with 98% sensitivity and 64% specificity.36 Further questions were determined based on the eligibility criteria for various federal and provincial benefits and tax credit programme. The tool was first used at a community health centre and with a family health team in Toronto for 1 month to identify technical problems. Following feedback sessions with providers, modifications were made to the tool to improve its overall design for use in this study.

Study procedures

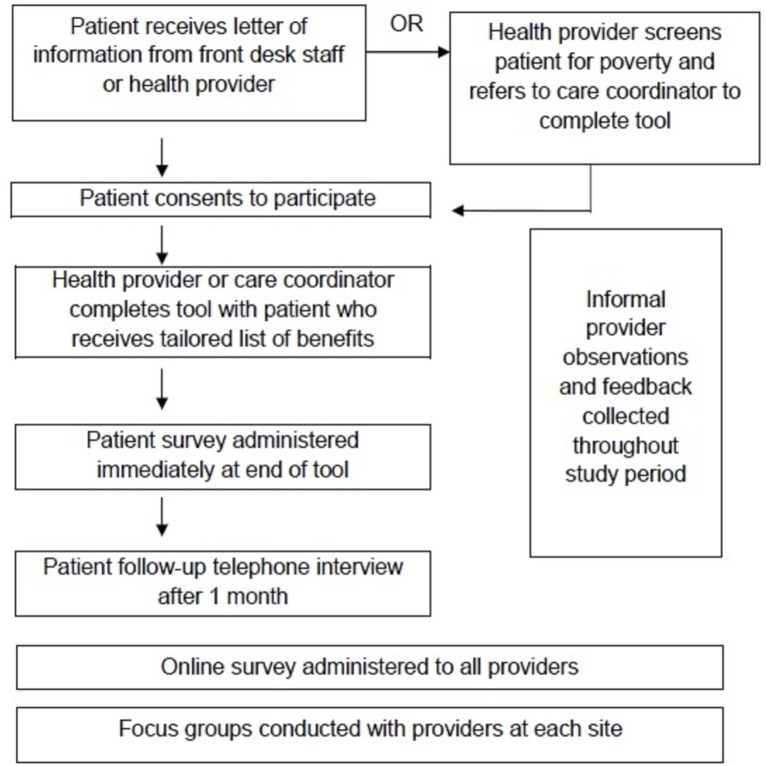

An orientation session will be held at each site to introduce primary care providers to the tool and enrol them in the study as participants. Following this session, the tool will be implemented for a 3-month period. The tool can be used by any member of the healthcare team, including physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, patient navigators and social workers. Each site will have some flexibility in how the tool will be implemented into the routine workflow of patient care, based on input from providers at the site. Health providers will be encouraged to use the tool with every patient seen. The tool can also be used in an opportunistic way when patients share a health concern that is linked to low income. Patients who consent to participate in the study can then use the tool with their health provider. At this time, study sites do not have a formal, systematic way to identify low-income patients. To minimise bias by providers or reception staff, all patients who present for care in these clinics will be approached. This intervention was not randomised because excluding low-income patients from receiving information on eligible benefits and accessing additional income supports would be unethical. Moreover, the topic may come up in any given appointment depending on the nature of the visit. Given the limited time during appointments at some sites, family physicians will screen patients for low income and refer them to a care coordinator (eg, social worker) to complete the tool (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Implementation and evaluation of an online income tool.

Participants

Providers

The six clinics testing the tool will introduce the pilot study to healthcare providers and interested providers will be consented to participate. We will aim to have a diverse group of healthcare professionals use the tool with patients including family physicians, nurse practitioners, social workers and patient navigators.

Patients

All patients seen at the primary care site are eligible to complete the online tool with their provider. Health providers and clinic staff will inform patients of the study through information sheets provided at the front desk of clinics or during an appointment. After reviewing the information sheet, the patient will note that they consent to proceed. To preserve anonymity, signed consent from patients will not be sought. The inclusion criteria for the 1-month follow-up with patients is as follows: used the tool approximately 1 month ago with their healthcare provider, able to provide consent, 18 years old or above, able to converse in English and able to be reached via telephone or email.

Sample size

The primary aim of this pilot study is to assess the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention in a clinical setting and assess the short-term impact of the tool on patients. There is no predefined sample for patients completing the tool with their provider. This pilot study will help determine study sample calculations for future clinical trials and the usage and length of time to complete the tool will be monitored.37 Of those patients who complete the tool and survey, a subset will be contacted for follow-up. The target sample size for 1-month follow-up is 200 patients in each province for a total of 400 patients. We anticipate that this sample size will be robust enough to determine the acceptability of using the tool, as well as provide data on impact that will allow for sample size calculation for future studies of the impact of such tools on income itself.

Quantitative data collection

Online tool output

We will collect a set of data points on each use of the tool. We will not be able to distinguish repeat users. The tool will record answers to the following demographic questions: age, immigration status, employment status, whether someone in the household has a disability, household income and how many people live in the household and any existing benefits or tax credits received by the patient. The tool will also track clinic site, start time and end time of use, benefits recommended (output of tool) and proportion of users who complete the tool.

Patient surveys

At the end of the tool, patients will be asked to complete a brief survey on their experience of using the tool and to provide contact information if interested in being contacted in the future. This survey will capture whether patients found the tool helpful, whether they would recommend the tool to a friend or family member and whether they understood the information provided to them. Lastly, the survey will use a Likert scale for patients to mark their confidence in taking next steps based on the information provided to them following their initial use of the tool with providers. Since there are no standardised instruments for evaluating this type of intervention the research team developed surveys to learn about patient perceptions of the tool after immediate use. At the end of the tool, we will ask patients’ permission to have a research coordinator follow-up with them via telephone or email to conduct a structured interview 1 month after their use of the tool in the clinic. This subset will be a convenience sample of all patients who provide their contact information and consent to an interview.

Qualitative data collection

Provider focus groups and survey

Three months after participating in the online income tool pilots, providers will be asked to complete an online, anonymous survey about their experience of using the tool. The purpose of this survey is to understand the providers’ perspective on whether they would use the tool in the future and whether they would recommend it to a colleague. Surveys will also capture how many times providers used the tool, whether providers felt they had enough time to do the tool with their patients, as well as the biggest benefit and drawback of using the tool, respectively. Providers at each site will also participate in a focus group discussion that explores the use of the tool over the last 3 months and the barriers and facilitators to implementation. Focus groups will provide a setting for in-depth discussion around the tool’s integration into regular clinical workflow, suggestions for its improvement, provider attitudes about addressing poverty in primary care, as well as factors that inhibited use of the tool during piloting at each site. A set of questions will be used to guide the focus groups and the discussions will be audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim.

Provider observations and feedback

During the 3-month period of pilot testing the online income tool at three sites in Winnipeg and Toronto, respectively, the use of the tool and its accompanying feedback from study team members and participating staff is being collected on an ongoing basis. Analytics regarding the number of times the tool is being used at each site are recorded and shared with study team members on a weekly basis and any feedback shared about the tool in informal conversations during site visits, through email or interim reports is noted in a feedback matrix that will be used when developing the tool in preparation for its next phase of use.

Analysis plan

Quantitative analysis

The primary outcome of this study is patient and provider perceptions around the integration of a tool addressing income in primary care settings (assessed through patient surveys, telephone interviews with patients at 4 weeks, provider focus groups and provider surveys). Additional outcomes that will be measured include patient access to financial benefits 4 weeks after their use of the tool (assessed through telephone interview at 4 weeks) (table 2). Descriptive statistics will be calculated (counts, percentages, means) to summarise variables including patient characteristics, usage of the tool and patient outcomes for all six sites. Outcome measures will be dichotomous and a bivariate analysis (using Student t-tests and χ2 tests, as appropriate) will be performed to determine associations between patient characteristics recorded from the tool and outcome measures (eg, whether programme was helpful, whether the patient is confident in taking next steps and whether their financial situation improved). Independent variables associated with positive patient outcomes and negative patient outcomes will be analysed separately. Logistic regression analysis will be performed to identify variables independently associated with patient outcome measures.

Table 2.

Main outcome measures for implementation and impact of tool

| Measure | Source | Method of data collection | Domain | Time point |

| Acceptability of tool | Provider | Provider focus group and survey, patient survey and telephone interview | Acceptability | After 3-month study period |

| Feasibility of tool | Provider | Provider focus group and survey, patient survey and telephone interview | Feasibility | After 3-month study period |

| Change in income | Patient | Patient follow-up interview | Effectiveness | 1 month |

| Change in knowledge of benefits | Patient | Patient follow-up interview | Effectiveness | 1 month |

Qualitative analysis

A secondary outcome that will be assessed in this study is the providers’ perspectives on the feasibility and acceptability of the tool using qualitative analysis. The field notes and transcripts of the focus groups with providers will be analysed thematically.38 An initial coding framework will be developed using the focus group guide. Two team members will independently read and code transcripts using Dedoose V.7.0.23 (SocioCultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, California, USA). Themes will be refined in an iterative process by comparing codes with the research team and reaching consensus on a final coding framework. The thematic analysis will focus on identifying key facilitators and barriers to implementation and provider perspectives on the impact of the tool and ways to improve similar tools. Field notes collected throughout the study will help contextualise findings for each site and identify similarities and differences across sites. Open-ended questions from patient and provider surveys will also be thematically coded and categorised. We will identify common experiences associated with using the tool that may provide insight into how the tool works and ways to improve similar tools in the future.

Advisory group

We will organise an advisory committee made of up patients, community agencies and staff to provide ongoing feedback on the project. Our aim is to engage four to six patients to provide input on how to improve the online tool and its use in clinical settings. For this study, the advisory committee will play an important role in understanding how to improve the tool interface and what information will be most useful for patients to improve the tool output. The advisory committee will meet approximately once a month beginning in July 2016 until the end of data collection to help interpret findings, make recommendations to the online tool and suggestions for integrating its use within the care team. Ongoing engagement with patients and stakeholders will help to determine modifications to the tool, contextualise our findings and promote greater uptake in the future.39

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by St Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board, the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Manitoba and the Michael Garron Hospital Research Ethics Board. Informed consent will be obtained for all study participants. Data collected by the online tool will be anonymous, with no link between answers to questions in the tool and personal identifying data. Some patients may feel discomfort when asked the screening question and they may feel shame or fear stigma if they are experiencing income insecurity. We will attempt to lessen this possibility by encouraging health providers to normalise the experience for patients, for example, “I’m asking many of my patients this question over the next 3 months”. Patients may feel obligated to complete the tool with their healthcare providers. During training sessions, all providers will be asked to emphasise that this intervention is optional and not part of routine care. Patients will also be informed that they can stop using the tool at any time. Healthcare providers will also be trained to manage patient expectations by stating that this tool may or may not identify benefits which could provide increased income. All patient and provider surveys will be anonymised. Finally, participants in focus groups will not be identified by name and all transcripts will be anonymised during transcription.

This study uses an ‘upstream’ approach to address a root cause of poor health outcomes: poverty. By exploring the feasibility and acceptability of using an online tool we can establish a standardised process to screen patients for low income in routine primary care settings. We will also examine and report on local factors that influence implementation at the different clinic sites. Moreover, the implementation of the tool will be pragmatic, with the ultimate aim to bring such tools into broader practice through integration into primary healthcare settings. The findings from this study will provide insight into individual-level interventions to address the social determinants of health in primary care. Such tools may be useful to a diversity of primary care providers and could be applicable to other healthcare settings, such as in discharge planning at healthcare institutions. Important strengths of the intervention include opportunities for providers to offer feedback on the content, design and overall usability of the tool and the follow-up with patients about changes in their financial situation. Patients and community agencies represented in the advisory group will help ensure that this study remains focused on patient-centred outcomes and experiences and will contribute particular perspectives to the interpretation of our findings.

We will evaluate the implementation and short-term effects of this online income security tool within six health clinics. We will attempt to engage a broad representation of health providers at each site and will invite all staff to participate in our study. The information provided in the output of the tool may not be suitably tailored to the needs of all individuals. The time frame of this study does not permit us to examine health effects, which we would anticipate would take longer than 1 month to develop, and which would require a more intense intervention. Future research could examine whether using this tool, in coordination with other services, with patients identified as being at risk of developing complex health and social needs could impact on health and health service use.2 40 The hypothesis tested would be that that addressing income security may reduce the risk of poor health and high service use for some patients.

There are several limitations to the proposed the study. First, the study uses a convenience sampling method so participants who declined to use tool or could not be reached at follow-up were not captured. Second, the sites chosen to pilot the tool were already interested in addressing income security at their clinics. Furthermore, all site materials were in English so findings may not be generalisable to other clinical settings. Lastly, while we anticipate that the tool will be able to identify benefits that a patient could be eligible for, the complex process of applying for benefits may be a barrier to improving income security and a 1-month follow-up may be too short of a time frame within which to assess impact. However, this is one of the few studies on SDOH interventions that follows up with patients and a major strength is implementing the tool across multiple sites in two provinces.

This study is timely as awareness and a commitment to act on the SDOH is growing within the health sector in Canada6 22 41 42 and globally.43–45 Continuing medical education events on poverty and health have been established and new medical school curricula is being created.46 These efforts may begin to change medical practice. Yet, there are few studies that have evaluated the implementation and impact of such initiatives. The findings of this study will contribute to the design of SDOH interventions in healthcare, particularly when considering the role of technology and the practical challenges of incorporating interventions into busy health organisations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all our collaborators at Prosper Canada, particularly Adam Fair, Marlene Chiarotto and Layla Rich, without whom this work would not be possible. We also acknowledge the input of our Income and Health Advisory Group members.

Footnotes

Twitter: @AndrewDPinto @upstreamlab

Contributors: ADP conceived the study. AS, GH, GB, RG, DR, REGU, JB, AK and ADP provided key inputs into the design of the study and refinements of the protocol. AA, AR and ADP assisted in the writing of the first draft of the manuscript. ADP, AS, GH, GB, RG, REGU and AK assisted with obtaining funding for the study. All authors contributed to critical revisions and editing the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript. ADP had full access to all the information present and takes responsibility for the accuracy of this paper.

Funding: This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN: 142877), Intuit Foundation, Research Manitoba and the St Michael’s Hospital Foundation. None of the funders played any role in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data or in writing or editing this manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the St Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board (15-353), the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Manitoba (HS19275:H2016:019) and the Michael Garron Hospital Research Ethics Board (691-1608-Mis-298).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation. Geneva;2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosella LC, Fitzpatrick T, Wodchis WP, et al. . High-cost health care users in Ontario, Canada: demographic, socio-economic, and health status characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:532 10.1186/s12913-014-0532-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baum FE, Legge DG, Freeman T, et al. . The potential for multi-disciplinary primary health care services to take action on the social determinants of health: actions and constraints. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1–13. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maeseneer J, Willems S, De Sutter A, et al. . Primary health care as a strategy for achieving equitable care: a literature review commissioned by the Health Systems Knowledge Network. 2007. www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/primary_health_care_2007_en.pdf

- 5. British Medical Association. Social determinants of health - what doctors can do. 2011.

- 6. Canadian Medical Association. Physicians and health equity: opportunities in practice. 2013.

- 7. Hassan A, Scherer EA, Pikcilingis A, et al. . Improving Social Determinants of Health: Effectiveness of a Web-Based Intervention. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:822–31. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kiran T, Pinto AD. Swimming “upstream” to tackle the social determinants of health. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:138–40. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adler NE, Ostrove JM. Socioeconomic status and health: what we know and what we don’t. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:3–15. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adler NE, Stewart J. Health disparities across the lifespan: meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1186:5–23. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hwang SW. Homelessness and health. Can Med Assoc J 2001;164:229–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tarasuk V, Cheng J, de Oliveira C, et al. . Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CMAJ 2015;187:E429–E436. 10.1503/cmaj.150234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kennedy G. Food for all. Can Med Assoc J 2007;177:1473 10.1503/cmaj.071635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vozoris NT, Tarasuk VS. Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. J Nutr 2003;133:120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Che J, Chen J. Food insecurity in Canadian households. Health Reports 2001;12:11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bartley M, Blane D, Davey Smith G. Introduction: Beyond the Black Report. Sociol Health Illn 1998;20:563–77. 10.1111/1467-9566.00119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch et al. BMJ 2001;322:1233–6. 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Davey Smith G, et al. . Change in health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:922–6. 10.1136/jech.56.12.922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marmot MG, Shipley MJ. Do socioeconomic differences in mortality persist after retirement? 25 year follow up of civil servants from the first Whitehall study. BMJ 1996;313:1177–80. 10.1136/bmj.313.7066.1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Acheson D. The Acheson Report : Purdy M, Banks D, The sociology and politics of health: a reader. London: Routledge, 2001:111–22. p.. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. Income inequality and population health: a review and explanation of the evidence. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:1768–84. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buchman S. Screening for poverty in family practice. Can Fam Physician 2012;58:709. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andermann A. CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ 2016;188:E474–83. 10.1503/cmaj.160177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Adams J, White M, Moffatt S, et al. . A systematic review of the health, social and financial impacts of welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings. BMC Public Health 2006;6:81 10.1186/1471-2458-6-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones MK, Bloch G, Pinto AD. A novel income security intervention to address poverty in a primary care setting: a retrospective chart review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014270 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, et al. . Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics 2015;135:e296–304. 10.1542/peds.2014-2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, et al. . Improving the management of family psychosocial problems at low-income children’s well-child care visits: the WE CARE Project. Pediatrics 2007;120:547–58. 10.1542/peds.2007-0398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boston Children’s Hospital. HelpSteps. 2016. http://www.helpsteps.com (accessed 10 Jun 2016).

- 29. Fleegler EW, Lieu TA, Wise PH, et al. . Families’ health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics 2007;119:e1332–41. 10.1542/peds.2006-1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wylie SA, Hassan A, Krull EG, et al. . Assessing and referring adolescents’ health-related social problems: qualitative evaluation of a novel web-based approach. J Telemed Telecare 2012;18:392–8. 10.1258/jtt.2012.120214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gottlieb L, Hessler D, Long D, et al. . A randomized trial on screening for social determinants of health: the iScreen study. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1611–18. 10.1542/peds.2014-1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Standish S, et al. . Addressing unmet basic resource needs as part of chronic cardiometabolic disease management. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:244–52. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gottlieb LM, Hessler D, Long D, et al. . Effects of Social Needs Screening and In-Person Service Navigation on Child Health. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:e162521Q 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bloch G. Poverty: a clinical tool for primary care in Ontario. http://effectivepractice.org/resources/poverty-a-clinical-tool-for-primary-care/ (accessed 12 Jun 2016).

- 35. Prosper Canada. 2016. http://prospercanada.org/About-Us/Overview.aspx (accessed 10 Jun 2016).

- 36. Brcic V, Eberdt C, Kaczorowski J. Development of a tool to identify poverty in a family practice setting: a pilot study. Int J Family Med 2011;2011:1–7. 10.1155/2011/812182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. . A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:1 10.1186/1471-2288-10-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ayala GX, Elder JP. Qualitative methods to ensure acceptability of behavioral and social interventions to the target population. J Public Health Dent 2011;71:S69–79. 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00241.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fitzpatrick T, Rosella LC, Calzavara A, et al. . Looking Beyond Income and Education. Am J Prev Med 2015;11:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Canadian College of Family Physicians. Best advice - Social determinants of health 2015.

- 42. Pinto AD, Glattstein-Young G, Mohamed A, et al. . Building a Foundation to Reduce Health Inequities: Routine Collection of Sociodemographic Data in Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med 2016;29:348–55. 10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gottlieb L, Sandel M, Adler NE. Collecting and applying data on social determinants of health in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1017–20. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gottlieb LM, Tirozzi KJ, Manchanda R, et al. . Moving electronic medical records upstream: incorporating social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:215–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Garg A, Dworkin PH. Surveillance and screening for social determinants of health: the medical home and beyond. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:189–90. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ontario College of Family Physicians. Primary care interventions in poverty 2016. http://ocfp.on.ca/cpd/povertytool (accessed 7 Nov 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.