Abstract

Objective

To analyse the effectiveness of a household conditional cash transfer programme (CCT) on antenatal care (ANC) coverage reported by women and ANC quality reported by midwives.

Design

The CCT was piloted as a cluster randomised control trial in 2007. Intent-to-treat parameters were estimated using linear regression and logistic regression.

Setting

Secondary analysis of the longitudinal CCT impact evaluation survey, conducted in 2007 and 2009. This included 6869 pregnancies and 1407 midwives in 180 control subdistricts and 180 treated subdistricts in Indonesia.

Outcome measures

ANC component coverage index, a composite measure of each ANC service component as self-reported by women, and ANC provider quality index, a composite measure of ANC service provided as self-reported by midwives. Each index was created by principal component analysis (PCA). Specific ANC component items were also assessed.

Results

The CCT was associated with improved ANC component coverage index by 0.07 SD (95% CI 0.002 to 0.141). Women were more likely to receive the following assessments: weight (OR 1.56 (95% CI 1.25 to 1.95)), height (OR 1.41 (95% CI 1.247 to 1.947)), blood pressure (OR 1.36 (95% CI 1.045 to 1.761)), fundal height measurements (OR 1.65 (95% CI 1.372 to 1.992)), fetal heart beat monitoring (OR 1.29 (95% CI 1.006 to 1.653)), external pelvic examination (OR 1.28 (95% CI 1.086 to 1.505)), iron-folic acid pills (OR 1.42 (95% CI 1.081 to 1.859)) and information on pregnancy complications (OR 2.09 (95% CI 1.724 to 2.551)). On the supply side, the CCT had no significant effect on the ANC provider quality index based on reports from midwives.

Conclusions

The CCT programme improved ANC coverage for women, but midwives did not improve ANC quality. The results suggest that enhanced ANC utilisation may not be sufficient to improve health outcomes, and steps to improve ANC quality are essential for programme impact.

Keywords: health economics, health policy, community child health, public health, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study takes advantage of the cluster randomisation of the conditional cash transfer and the longitudinal impact evaluation survey which included near-poor and poor households. The findings are therefore representative of the relevant population and may apply to similar policies in other low-income and middle-income countries.

The study goes beyond assessment of simple (antenatal care) ANC attendance or quality and accounts for coverage of specific components of ANC and quality as reported by women and midwives.

Measurement error and recall bias may limit the interpretation of the study since women with older children might not accurately recall the services received during pregnancy.

Introduction

Maternal and child health is of global importance, and current data indicate 99% of all maternal and neonatal deaths occur in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 2 To improve maternal and child health, many LMICs have widely implemented household conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes. CCT programmes provide cash transfers to poor households conditional on meeting prespecified health and education requirements.

CCT programmes have been shown to improve access to healthcare services, but the results are mixed with respect to health outcomes.3 4 Benefits were seen for Brazil’s CCT programme that led to lower child mortality5 and for India’s CCT programme, which targeted facility-based delivery, and reduced neonatal mortality.6 Mexico’s CCT programme led to a modest increased birth weight and a 4% decline in low birth weight.7–9 Mexico’s programme also led to a 1.1 SD increase in height among children under 6 months, but with little effect on older children.10 Colombia’s CCT programme was associated with a 16% increase in height-for-age z-score for children under 24 months. In contrast, there were no statistically significant effects on children’s health status for programmes in Nicaragua or Ecuador.3 11–13 These data suggest that factors other than the CCT, such as health provider context or service, may influence the impact of programmes.

The Indonesian CCT programme, Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH, the Hopeful Family Programme), was deployed as a cluster-randomised controlled trial in 2007. The Government of Indonesia implemented PKH in response to poor health and educational outcomes among the poor.14 In 2007, Indonesia’s infant mortality was 31 per 1000 live births and low birth weight was 9%.15 16 One goal was to reduce infant mortality and low birth weight, as the latter adversely affects subsequent outcomes including mortality, morbidity and educational outcomes.17–19 PKH’s CCT requirements included: at least four antenatal care (ANC) visits, delivery assistance from a doctor or midwife, postnatal care and complete vaccination. Initial reports indicated PKH improved ANC attendance, but had no effect on low birth weight.3 14 20 ANC can improve pregnancy outcomes, but attendance alone may be insufficient.21 22 It is unclear whether ANC utilisation is accompanied by improved coverage of the recommended ANC service items.14 20 One potential explanation for the lack of impact on outcomes is low ANC provider quality.23 There is limited evidence on the link between increased ANC attendance and ANC provider quality.20 22 24–26 This study extends earlier reports by exploring ANC component coverage for specific service items and ANC provider quality of midwives. We therefore add to the current understanding on how CCT programmes affect ANC services as a channel to improve pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

Study design and data source

A secondary data analysis was performed using pre-existing PKH impact evaluation surveys. PKH was deployed in Jakarta and West Java, East Java, North Sulawesi, Gorontalo and East Nusa Tenggara provinces. Randomisation was done at the subdistrict level as the smallest unit of facility management that would also reduce the risk of spillover to control areas14; 329 subdistricts were randomised into treatment and 259 to control. Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik) used proxy-means test for all poor households in treatment subdistricts to identify extremely poor households with expectant or lactating women, children under 5 and school-aged children (6–18 years).

PKH delivered quarterly cash transfers to expectant women and mothers of the children in enrolled households. Households with pregnant or lactating mothers would receive 1 000 000 Rupiah (US$100) and another 800 000 Rupiah (US$80) if there were children under 6 years. The maximum transfer was 2 200 000 Rupiah (US$220). The amount was 15% to 20% of estimated total monthly consumption of poor households. Verification for compliance was conducted monthly by facilitators who collected patient and service lists from healthcare providers. Households generally received the transfers conditional on meeting at least one requirement.

The PKH impact evaluation survey was conducted in 2723 villages in 180 randomly selected treatment and 180 control subdistricts. The baseline was conducted between June and August 2007, before implementation in November 2007. The follow-up was conducted between October and December 2009, attrition at the household level was 4%. The surveys included near-poor and poor households and midwives. Design details are available in the impact evaluation report.14

The longitudinal household survey included current pregnancies and deliveries 24 months prior to each survey wave. The baseline included 4700 pregnancies and deliveries between June 2005 and August 2007. The follow-up included 2168 pregnancies and deliveries between October 2007 and December 2009. Pregnancy history included self-reported information on each pregnancy, including delivery assistance, prenatal and postnatal care service items. Recall bias and measurement error may have influenced data quality, but the relatively short time window of 24 months would tend to limit overall bias. At the follow-up survey in 2009, women were asked if they received ANC in public or private practice.

The accompanying provider survey included practicing community-based midwives since they are the primary skilled delivery attendants, especially in rural areas.27 28 Four midwives per subdistrict were selected. Midwives employed by the government are allowed to hold dual practice, that is, private practice undertaken by healthcare workers employed in the public sector. In our sample, more than 80% of midwives were in dual practice. At baseline, 2800 midwives were interviewed. At follow-up, midwives self-reported the ANC service items provided in their public and private practice. There were 1396 observations from midwives in public practice and 1269 observations from private practice.

Variables and covariates

This study examined women’s self-reported ANC coverage of specific service components and midwives’ self-reported ANC provider quality based on service components.

At the individual client level, the outcomes of interest were ANC service items received during pregnancy. Changes in ANC component coverage were estimated using an ANC component coverage index, constructed using principal component analysis (PCA) of all prenatal service items. The items included are based on the Indonesian Ministry of Health guidelines.29 They were the following dichotomous variables: measurement of women’s weight, height, blood pressure, fundal height, fetal heartbeat, a blood test (for syphilis and HIV), external and internal pelvic examination, receiving 90 iron-folic acid pills, two tetanus toxoid vaccinations, information on signs of pregnancy complications and being told what to do if there were signs of pregnancy complications. The survey excluded perception of quality and other social aspects. The following sociodemographic characteristics were also included: indicators for child sex and first child (conditional on live birth), mother’s education, mother’s age at delivery, monthly household expenditure (expressed as log monthly per capita expenditure in 2007 Rupiah) and asset ownership at baseline.

At the provider level, the outcomes of interest were ANC service items provided by midwives in their public and private practice. The ANC provider quality index was constructed using PCA based on self-reported prenatal service items performed. The items included the following dichotomous variables: the measurements of woman’s weight, height, blood pressure, blood test, urine test, internal and external pelvic examinations, fundal height, and fetal heartbeat, iron pills, information on pregnancy complications, nutrition and the development of a facility-based delivery plan. Midwives also self-reported the average time spent per prenatal visit in the first trimester.

Study population

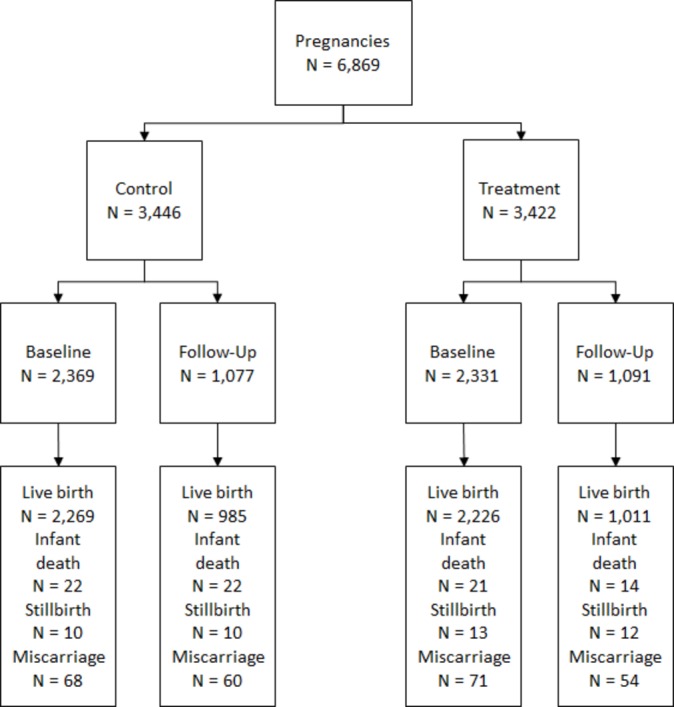

We estimated the programme’s effect on ANC coverage using women’s pregnancy history. We include all reported pregnancies and deliveries at baseline and follow-up. Figure 1 presents the number of pregnancies in the analysis. At baseline, there were 2369 pregnancies in the control group and 2333 pregnancies in the treated group. At follow-up, there were 1077 pregnancies in the control group and 1091 pregnancies in the treated group.

Figure 1.

Study population.

The midwife survey was used to estimate the programme’s effect on ANC provider quality. The ANC provider quality was only asked at follow-up, so the analysis was based on cross-sectional data. The analysis included 1396 midwives to estimate differences in ANC provider quality in their public and private service.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA MP V.13.0. We exploited the cluster randomisation of PKH to estimate the intent-to-treat (ITT) parameters. We compared respondents in sub-districts who were randomised into treatment to those in the control subdistricts, adjusting for district-level fixed effects to capture non-time-varying district characteristics and clustering all SEs at the subdistrict level to adjust for the subdistrict level of cluster randomisation. We used least squares regressions for all continuous outcome variables: ANC component coverage index and ANC provider quality index. The OR and 95% CI for dichotomous outcomes were calculated using logistic regressions. The dichotomous items included the list of ANC service items.

At the individual client level, we used each self-reported prenatal service item as a dichotomous outcome and created a continuous ANC component coverage index using all antenatal service items. The ANC component coverage index was created using STATA’s built-in command, pca. Socio-demographic characteristics were included as covariates. Bartlett’s sphericity test (p value <0.001) and Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) index (0.736) indicate the items could be summarised using PCA. The PCA performed on the listed variables resulted in three components with eigenvalues greater than 1. We selected the primary component which accounted for 61% of the variance, and the component score for each woman was her ANC component coverage index. For robustness, we generated an alternative ANC component coverage index using STATA’s built-in command, tetrachoric, to take into account the dichotomous items. We conducted a separate cross-sectional analysis to estimate differences in prenatal component coverage in public and private practice from the follow-up survey.

At the midwife level, we used each self-reported prenatal service item in public and private practice at follow-up. While a longitudinal analysis would be preferred, as mentioned above, the data are only available as a cross-section, and this may limit interpretation of the results. However, the subdistrict randomisation showed that other characteristics at baseline were balanced, thereby suggesting the analysis would permit valid inference. We coded each item as a dichotomous outcome and created a continuous ANC provider quality index using all antenatal care items. The ANC provider quality index at the midwife level was created using the same built-in command, pca. Bartlett’s sphericity test (p value <0.001) and KMO index (0.796) indicate the items could be summarised by PCA. The PCA performed on the listed variables resulted in two components with eigenvalues greater than 1. We selected the primary component which accounted for 84% of the variance in public practice and 80% in private practice. For robustness, we also generated an alternative ANC provider quality index using STATA’s built-in command, tetrachoric, to take into account the dichotomous items.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 presents women’s characteristics at baseline. Baseline characteristics were similar across treatment and control groups. The majority of women in the sample were under 30 years of age in 2007. Since PKH targeted poor households, the majority were indeed low socio-economic status. About 70% of women in the sample had 6 years of education or less. Per capita total household expenditure was 160 000 Rupiah per month (US$16) at baseline. Land ownership was around 35% and home ownership was 86% in the control group. The low asset ownership and household expenditure were consistent with high poverty rates in the analysed sample. Baseline pregnancy outcomes were similar across the treatment and control groups. About 48% of women delivered a male child, and 22% had their first child in our analysed sample at baseline. In all our analyses, an indicator for missing covariate is included to take into account the missing observations.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics*

| Treatment | Control | |||||

| n=2331 | n=2369 | Adjusted | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | difference | 95% CI | |

| Age | ||||||

| <25 | 27.23% | 44.52% | 26.68% | 44.24% | 0.0066 | (−0.0198 to 0.0330) |

| 26–30 | 25.30% | 43.48% | 25.12% | 43.38% | 0.0022 | (−0.0213 to 0.0258) |

| 31–35 | 24.14% | 42.80% | 24.31% | 42.91% | −0.0031 | (−0.0274 to 0.0213) |

| >35 | 23.33% | 42.30% | 23.89% | 42.65% | −0.0058 | (−0.0305 to 0.0190) |

| Missing observations | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| 6 years or less | 73.02% | 44.40% | 72.40% | 44.71% | 0.0099 | (−0.0188 to 0.0387) |

| 6–9 years | 19.06% | 39.28% | 20.17% | 40.14% | −0.0141 | (−0.0383 to 0.0101) |

| 9 years or more | 7.92% | 27.02% | 7.44% | 26.24% | 0.0042 | (−0.0117 to 0.0201) |

| Missing observations | 141 | 117 | ||||

| Asset ownership | ||||||

| Land ownership | 34.35% | 47.50% | 36.22% | 48.07% | −0.0188 | (−0.0486 to 0.0110) |

| Home ownership | 88.16% | 32.31% | 86.41% | 34.28% | 0.0168 | (−0.00341 to 0.0370) |

| Missing observations | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Per capita household expenditure† | 1 58 320 | 89 709 | 1 64 114 | 89 709 | −6.093 | (−11,397 to −789.7) |

| Missing observations | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Male child | 47.47% | 49.95% | 47.53% | 49.95% | −0.0002 | (−0.0278 to 0.0274) |

| Missing observations | 58 | 73 | ||||

| First child | 22.56% | 41.80% | 21.53% | 41.11% | 0.0094 | (−0.0141 to 0.0329) |

| Missing observations | 68 | 49 | ||||

| Outcome variables | ||||||

| Any antenatal service | 74.44% | 43.63% | 73.62% | 44.08% | 0.0075 | (−0.0219 to 0.0367) |

| Antenatal care component coverage index | 0.101 | 0.967 | 0.068 | 0.986 | 0.0317 | (−0.0324 to 0.0958) |

| Antenatal care service components | ||||||

| Weight | 83.19% | 37.40% | 82.06% | 38.38% | 0.0100 | (−0.0143 to 0.0342) |

| Missing observations | 257 | 289 | ||||

| Height | 40.18% | 49.04% | 41.71% | 49.32% | −0.0181 | (−0.0495 to 0.0133) |

| Missing observations | 267 | 299 | ||||

| Blood pressure | 83.62% | 37.02% | 83.07% | 37.51% | 0.0042 | (−0.0188 to 0.0273) |

| Missing observations | 293 | 261 | ||||

| Blood test | 33.15% | 47.08% | 33.43% | 47.19% | −0.0016 | (−0.0306 to 0.0274) |

| Missing observations | 271 | 304 | ||||

| Fundal height | 45.45% | 49.80% | 44.24% | 49.68% | 0.0107 | (−0.0211 to 0.0424) |

| Missing observations | 270 | 304 | ||||

| Fetal heartbeat | 76.03% | 42.70% | 73.62% | 44.08% | 0.0239 | (−0.00260 to 0.0505) |

| Missing observations | 262 | 293 | ||||

| Internal examination | 20.11% | 40.09% | 20.22% | 40.17% | −0.0011 | (−0.0251 to 0.0230) |

| Missing observations | 272 | 312 | ||||

| External examination | 23.97% | 42.70% | 24.65% | 43.11% | −0.0063 | (−0.0314 to 0.0188) |

| Missing observations | 314 | 274 | ||||

| Received >90 iron pills | 12.78% | 33.39% | 12.11% | 32.64% | 0.0043 | (−0.0181 to 0.0266) |

| Missing observations | 33 | 51 | ||||

| Complete tetanus toxoid | 58.19% | 49.34% | 57.58% | 49.43% | 0.0086 | (−0.0227 to 0.0399) |

| Missing observations | 695 | 599 | ||||

| Information on signs of pregnancy complications | 33.40% | 47.18% | 31.57% | 46.49% | 0.0182 | (−0.0122 to 0.0487) |

| Missing observations | 257 | 286 | ||||

| Told what to do in case of pregnancy complications | 31.09% | 46.30% | 28.66% | 45.23% | 0.0246 | (−0.00514 to 0.0543) |

| Missing observations | 950 | 946 | ||||

*Baseline differences adjusted for district fixed effects, and clustered randomisation at the subdistrict level.

†US$1 was approximately 10 000 Rupiah. Real prices and expenditures were obtained based on the Consumer Price Index from Statistics Indonesia.

Antenatal coverage was high at baseline: about 75% of women reported receiving any antenatal care (74.4% in treatment vs 73.6% control). The ANC component coverage index of women was also similar (0.10 in treatment vs 0.07 control). About 80% of women had their weight measured at least once during pregnancy, 40% had their height measured, 83% had their blood pressure taken, 33% underwent a blood test, 45% had their fundal height measured and more than 70% had at least one fetal heartbeat examination. Only 20% of women received at least one internal and external pelvic examinations. This low proportion may be due to the possibility of limited examination rooms at healthcare facilities (only 54% of facilities have a separate maternal and child health or family planning examination room) and cultural norms on reproductive health.30 31 About 30% of women reported receiving information on signs of pregnancy complications, and about 30% were also told what to do if there were signs of pregnancy complications. Almost 60% of women reported receiving the complete set of two tetanus toxoid vaccinations during pregnancy.

A 30-day supply of iron-folic acid pills should be given to women as part of every ANC visit. Only 12% of women reported receiving at least 90 iron-folic acid pills during pregnancy, although about 80% of women received iron-folic acid pills at least once during pregnancy. This large discrepancy suggests women received iron supplementation at least once during their ANC visit, but women may show poor compliance to ANC visits, causing them to not receive the iron supplementation, or women do not receive iron supplementation during their ANC visit due to providers’ omission or insufficient stocks. To address both ANC visits and iron supplementation, compliance with ANC visit guidelines became part of the CCT programme’s requirements.14

ANC component coverage

One of the objectives of PKH was to increase healthcare access and utilisation among poor households, including ANC. Table 2 presents changes in ANC component coverage, which came from women’s self-report. Women living in treated communities received a 0.072 SD increase in PNC component coverage index (95% CI 0.002 to 0.141; p=0.057). Using an alternative ANC component coverage index to take into account dichotomous variables yielded similar results (0.090; 95% CI 0.0646 to 0.116; p<0.001).

Table 2.

The effects of PKH on antenatal care coverage*

| Pooled | Public practice, cross-sectional data from follow-up survey | Private practice, cross-sectional data from follow-up survey | ||||

| n=6869 | n=1378 | n=581 | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| ANC component coverage index† | 0.072 | (0.002 to 0.141) | −0.005 | (−0.131 to 0.120) | 0.022 | (−0.113 to 0.158) |

| ANC service components | ||||||

| Weight | 1.558 | (1.247 to 1.947) | 0.594 | (0.352 to 1.005) | 1.690 | (0.576 to 4.958) |

| Height | 1.407 | (1.164 to 1.700) | 0.897 | (0.675 to 1.192) | 1.391 | (0.966 to 2.003) |

| Blood pressure | 1.356 | (1.045 to 1.761) | 1.197 | (0.731 to 1.959) | 0.364 | (0.148 to 0.894) |

| Blood test | 1.058 | (0.871 to 1.285) | 0.985 | (0.715 to 1.356) | 0.878 | (0.560 to 1.377) |

| Fundal height | 1.654 | (1.372 to 1.992) | 1.012 | (0.745 to 1.374) | 1.584 | (1.049 to 2.393) |

| Fetal heart beat | 1.290 | (1.006 to 1.653) | 1.104 | (0.722 to 1.688) | 0.828 | (0.425 to 1.611) |

| Internal examination | 0.875 | (0.708 to 1.080) | 0.869 | (0.641 to 1.177) | 1.022 | (0.592 to 1.766) |

| External examination | 1.279 | (1.086 to 1.505) | 0.815 | (0.625 to 1.064) | 1.175 | (0.789 to 1.750) |

| >90 iron pills | 1.418 | (1.081 to 1.859) | 1.055 | (0.721 to 1.542) | 0.769 | (0.404 to 1.465) |

| Tetanus vaccinations | 0.897 | (0.746 to 1.077) | 1.035 | (0.796 to 1.346) | 0.945 | (0.600 to 1.488) |

| Pregnancy complications | ||||||

| Information on signs | 2.097 | (1.724 to 2.551) | 1.119 | (0.842 to 1.488) | 0.907 | (0.588 to 1.399) |

| Told what to do | 1.970 | (1.605 to 2.417) | 1.091 | (0.839 to 1.419) | 0.857 | (0.559 to 1.316) |

*Pooled analysis included pregnancies from baseline and follow-up, cross-sectional analysis came from follow-up. Covariates included were: indicators for male child and first child, mother’s education, mother’s age, log per capita expenditure and indicators for home and land ownership at baseline. District fixed effects included in all specifications. CIs in parentheses, clustered at the subdistrict level.

†Continuous variable.

ANC, antenatal care; PKH, Program Keluarga Harapan.

Compared with women living in control communities, women living in treated communities were more likely to receive the following services during pregnancy: weight measurement (OR 1.56; 95% CI 1.247 to 1.947; p<0.001), height measurement (OR 1.41; 95% CI 1.164 to 1.700; p<0.001), blood pressure measurement (OR 1.36; 95% CI 1.045 to 1.761; p=0.023), fundal height measurement (OR 1.65; 95% CI 1.372 to 1.992; p<0.001), fetal heartbeat measurement (OR 1.29; 95% CI 1.006 to 1.653; p=0.001), external pelvic examination (OR 1.28; 95% CI 1.086 to 1.505; p<0.001) or receiving more than 90 iron-folic acid pills (OR 1.42; 95% CI 1.081 to 1.859; p<0.001). Women were also more likely to receive information on pregnancy complications (OR 2.10; 95% CI 1.724 to 2.551; p<0.001) and information on what to do if there were signs of complications (OR 1.97; 95% CI 1.605 to 2.407; p<0.001). There were no statistically significant changes on the probability of receiving a blood test, internal examination or the probability of receiving two tetanus toxoid vaccinations during pregnancy. For sensitivity analysis, we created an alternative PNC component coverage index that excluded items that were either targeted by PKH or rarely received by women. When indicators for iron-folic acid pills, pelvic examinations and pregnancy complications were excluded, the estimated change in coverage was qualitatively similar. These results suggest that the CCT programme was successful in increasing the ANC component coverage during pregnancy.

With high levels of dual practice among midwives, we used the follow-up survey to examine the relationship between ANC services in public and private practice. Compared with women in control communities, we found that PKH had no statistically significant effect on ANC component coverage index in public or private practice. However, for women who went to public services, women in treated areas tended to be less likely to have their height measured (OR 0.59; 95% CI 0.352 to 1.005; p=0.052). Among women who went to private practice, women in treated areas tended to be more likely to receive the following: height measurement (OR 1.391; 95% CI 0.966 to 2.003; p=0.076) and fundal height measurement (OR 1.58; 95% CI 1.049 to 2.393; p=0.029). Women who chose private over public practice for ANC may differ in their observed and unobserved characteristics, so these estimates cannot be interpreted causally. Nonetheless, the results suggest differences that warrant future research.

ANC provider quality

A potential explanation for the poor impact of PKH on pregnancy outcomes is that improvements in ANC attendance or service component coverage only reflected better access to ANC at the current standards, but the actual care provided or follow-up actions by healthcare providers may have remained ineffective. Women from poor households may have limited access to ANC prior to PKH, and with increased access through PKH, women were able to obtain ANC, but midwives may still provide suboptimal care. To explore this, we compared the differences in the ANC component coverage index to midwives’ self-reported ANC provider quality index.

Table 3 presents differences in ANC provider quality. Compared with midwives in the control group, PKH had no statistically significant effect on ANC provider quality index in public (−0.036; 95% CI −0.352 to 0.281; p value=0.161) or private practice (−0.048; 95% CI −0.344 to 0.247; p value=0.150). The results were qualitatively similar using the alternative ANC provider quality index (0.0021 in public practice, −0.0324 in private practice). Compared with midwives in the control group, PKH had no statistically significant effect on each service provided in either public or private practice. Midwives reported spending 2 min less per antenatal visit (95% CI −3.332 to 0.263; p=0.094) in private practice. These results suggest that ANC provider quality in control and treated areas are similar. Therefore, improvements in ANC component coverage are likely driven by increased ANC utilisation.

Table 3.

The effects of PKH on antenatal care provider quality*

| Public practice | Private practice | |||

| n=1396 | n=1269 | |||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Quality index† | −0.036 | (−0.352 to 0.281) | −0.048 | (−0.344 to 0.247) |

| Service provided | ||||

| Weight | 1.097 | (0.767 to 1.570) | 0.976 | (0.637 to 1.497) |

| Height | 0.910 | (0.734 to 1.128) | 0.898 | (0.716 to 1.127) |

| Blood pressure | 0.948 | (0.667 to 1.347) | 0.905 | (0.590 to 1.388) |

| Blood test | 1.049 | (0.819 to 1.344) | 0.790 | (0.613 to 1.018) |

| Fundal height | 0.954 | (0.697 to 1.306) | 0.953 | (0.674 to 1.348) |

| Fetal heartbeat | 1.009 | (0.733 to 1.389) | 1.107 | (0.774 to 1.582) |

| Internal examination | 0.959 | (0.702 to 1.310) | 0.980 | (0.718 to 1.340) |

| External examination | 0.835 | (0.653 to 1.067) | 0.875 | (0.686 to 1.115) |

| Iron pills | 1.024 | (0.759 to 1.380) | 1.031 | (0.739 to 1.439) |

| Tetanus toxoid | 0.999 | (0.703 to 1.418) | 0.931 | (0.647 to 1.340) |

| Information on | ||||

| Signs of complications | 0.925 | (0.693 to 1.234) | 0.947 | (0.686 to 1.308) |

| Nutrition during pregnancy | 0.953 | (0.685 to 1.326) | 0.913 | (0.619 to 1.346) |

| Facility-based delivery | 0.997 | (0.741 to 1.341) | 0.985 | (0.714 to 1.358) |

| Time spent per antenatal visit | −0.253 | (−1.955 to 1.449) | −1.534 | (−3.332 to 0.263) |

*Cross-sectional analysis from follow-up survey. District fixed effects included in all specifications. CIs in parentheses, adjusted for clustered randomisation at the subdistrict level.

†Continuous variable.

PKH, Program Keluarga Harapan.

Discussion

This study compared the ANC component coverage received by women and the ANC provider quality rendered by midwives, the primary provider in this setting. The results of our study are consistent with the evidence showing the effectiveness of CCT programmes to improve health-seeking behaviour, including increasing ANC coverage.3 4 14 This study also showed that the CCT programme did not increase ANC provider quality, a finding that may account for the low impact on outcomes as previously reported. Limitations of the study include recall bias from clients and providers, and the cross-sectional versus a more robust longitudinal design. Nevertheless, taken together, the gap in ANC component coverage and the ANC provider quality suggests that the improvements in coverage were likely associated with improved access because of the programme requirements, but that additional action is needed to enhance quality and outcomes.

Programmes that incentivise women such as CCTs have been shown to increase the number of patients at healthcare facilities. Higher demand for services may burden providers, which in turn may lead to lower quality of care.14 32 Fortunately, we found no significant evidence of lower quality of care provided in response to the programme since PKH was rolled out in supply-ready communities, that is, communities had sufficient healthcare providers and facilities. In this case, healthcare providers respond to higher demand on the price dimension in private practice, instead of the quality dimension.20 When incentives are only provided to patients, we find improved health-seeking behaviour, but not improved health outcomes. In this setting, healthcare providers have no incentive to improve the quality of service provided, and this may partly explain the limited health improvements as previously mentioned.

The role of dual practice is important in the context of many LMICs, including Indonesia. Private practice is associated with supplier-induced demand,33 34 which tends to be associated with overconsumption of healthcare services. However, private practice is associated with increased supply of healthcare.27 The results showed that the improvement in ANC component coverage was seen among women who sought private practice, which suggests the role of private practice in increasing women’s choice set. However, private practice is also associated with higher prices, which could be a barrier to healthcare access for poor households that are not enrolled in the programme. As PKH continues to expand and the implementation of Indonesia’s universal health coverage (UHC) grows, quality of care continues to be policy relevant.35 The interpretation of the results herein is limited by the cross-sectional analysis. The absence of longitudinal data on ANC provider quality did not allow us to capture quality changes over time. Nonetheless, the results suggest that the programme reduced inequality in access, but there may still be discrepancies in the quality dimension.23 36 37

The lack of improvements in the antenatal quality rendered by healthcare providers may explain the missing link between ANC clinical coverage received by women and pregnancy outcomes. These results showed the impact of the CCT programme on near-poor and poor households, which is representative of the relevant population. The Indonesia PKH CCT approach and the context in which it was deployed is similar to other programme and frontline health worker systems in LMICs, that is, frontline midwives or skilled birth attendants providing ANC and delivery services. Moreover, as UHC programme is increasingly engaged in reimbursement of midwives and skilled birth attendants, issues of quality are increasingly emerging as potential constraints.38 Therefore, our results may apply to similar policy settings globally. In terms of specific policy recommendation, combining demand-side programmes with a supply-side intervention to improve quality of care and increase the accountability of healthcare providers in providing better quality of care and action linked to specific ANC service components could be implemented to improve the effectiveness of health interventions. Programmes that incentivise healthcare workers such as pay-for-performance may improve the quality of service rendered. Further research should be conducted to better understand the link between healthcare access, quality of care and pregnancy outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the World Bank (Indonesia), the PNPM Support Facility, TNP2K Indonesia (Tim Nasional Percepatan Penanggulangan Kemiskinan; National team for the Acceleration of Poverty Reduction), Benjamin Olken, Vivi Alatas, and Julia Tobias. We also thank the Hewlett Foundation/IIE Dissertation Fellowship and the Harvard Kennedy School Indonesia Program for supporting the corresponding author on a scholarship to complete this work.

Footnotes

Contributors: MT was involved in formulating the hypotheses, design of the analysis and conducted the analyses, and drafted the manuscript. AHS contributed to formulating the hypotheses and the design of the analyses, assisted with interpretation of results and revising and finalising the manuscript. Both authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: Financial support for the programme and impact evaluation came from the Government of Indonesia, the Royal Embassy of the Netherlands, the World Bank and the World Bank PNPM Support Facility, which is supported by the governments of Australia, the UK, the Netherlands and Denmark, as well as a contribution from the Spanish Impact Evaluation Fund. Support for this manuscript was provided, in part, from the Higher Education Network Ring Initiative (HENRI) Program (USAID-Indonesia Cooperative Agreement AID-497-A-11-00002), a partnership between the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the SEAMEO Regional Centre for Food and Nutrition, University of Indonesia, University of Mataram, Andalas University, the Summit Institute of Development, and Helen Keller International. Researchers were completely independent from the funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was a secondary analysis of the deidentified impact evaluation survey, therefore this analysis was considered exempt from approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data request can be made through TNP2K Indonesia: http://www.tnp2k.go.id/en/data-indicators/-14/tnp2k-microdata-catalogue/

References

- 1. Oestergaard MZ, Inoue M, Yoshida S, et al. . Neonatal mortality levels for 193 countries in 2009 with trends since 1990: a systematic analysis of progress, projections, and priorities. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001080 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to2010. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and The World Bank, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fiszbein A, Schady NR, Ferreira FHG, et al. . Conditional cash transfers: reducing present and future poverty. Washington DC, USA: World Bank, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N. Conditional cash transfers for improving uptake of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. JAMA 2007;298:1900–10. 10.1001/jama.298.16.1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rasella D, Aquino R, Santos CA, et al. . Effect of a conditional cash transfer programme on childhood mortality: a nationwide analysis of Brazilian municipalities. Lancet 2013;382:57–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60715-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, et al. . India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet 2010;375:2009–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gertler P. Do conditional cash transfers improve child health? evidence from PROGRESA’s control randomized experiment. Am Econ Rev 2004;94:336–41. 10.1257/0002828041302109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barber SL, Gertler PJ. The impact of Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme, oportunidades, on birthweight. Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:1405–14. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02157.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barber SL, Gertler PJ. Empowering women: how Mexico’s conditional cash transfer programme raised prenatal care quality and birth weight. J Dev Effect 2010;2:51–73. 10.1080/19439341003592630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rivera JA, Sotres-Alvarez D, Habicht JP, et al. . Impact of the Mexican program for education, health, and nutrition (Progresa) on rates of growth and anemia in infants and young children: a randomized effectiveness study. JAMA 2004;291:2563–70. 10.1001/jama.291.21.2563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Attanasio O, Gómez LC, Heredia P, et al. . The short-term impact of a conditional cash subsidy on child health and nutrition in Colombia, 2005. Report summary: familias 3. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Macours K, Schady N, Vakis R. 2008. Cash transfers, behavioral changes, and the cognitive development of young children: Evidence from a randomized experiment. Policy Research Working Paper: 4759.

- 13. Paxson C, Schady N. Does money matter? The effects of cash transfers on child development in rural Ecuador. Econ Dev Cult Change 2010;59:187–229. 10.1086/655458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alatas V, Cahyadi N, Ekasari E, et al. . Main findings from the impact evaluation of indonesia’s pilot household conditional cash transfer program. Washington DC, USA: World Bank, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15. The World Bank Data Bank. Mortality rate, infant (per 1,000 live births). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN (accessed 23 Jun 2016).

- 16. The World Bank Data Bank. Low-birthweight babies (% of births). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.BRTW.ZS?page=1 (accessed 23 Jun 2016).

- 17. Almond D, Chay KY, Lee DS. The costs of low birth weight. Q J Econ 2005;120:1031–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Currie J. Healthy, wealthy, and wise: socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood, and human capital development. Journal of Economic Literature 2009;47:87–122. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Currie J, Vogl T. Early-life health and adult circumstance in developing countries. Annu Rev Econom 2013;5:1–36. 10.1146/annurev-economics-081412-103704 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Triyana M. Do health care providers respond to demand-side incentives? evidence from Indonesia. Am Econ J Econ Policy 2016;8:255–88. 10.1257/pol.20140048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Campbell OM, Graham WJ. Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet 2006;368:1284–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Evans WN, Lien DS. The benefits of prenatal care: evidence from the PAT bus strike. J Econom 2005;125:207–39. 10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.04.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Das J, Hammer J, Leonard K. The quality of medical advice in low-income countries. J Econ Perspect 2008;22:93–114. 10.1257/jep.22.2.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barber SL, Gertler PJ. Empowering women to obtain high quality care: evidence from an evaluation of Mexicofoxits conditional cash transfer programme. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:18–25. 10.1093/heapol/czn039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cookson TP. Working for inclusion? conditional cash transfers, rural women, and the reproduction of inequality. Antipode 2016;48:1187–205. 10.1111/anti.12256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lavinas L. 21st century welfare. New Left Review 2013;1:5–40. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rokx C, Giles J, Satriawan E, et al. . New insights into the provision of health services in Indonesia: a health workforce study. South Jakarta, Indonesia: The World Bank, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heywood P, Harahap NP, Ratminah M, et al. . Current situation of midwives in Indonesia: evidence from 3 districts in West Java Province. BMC Res Notes 2010;3:287 10.1186/1756-0500-3-287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia (The Indonesian Ministry of Health). Pedoman pelayanan antenatal : Direktorat Bina Pelayanan Medik Dasar, Departemen Kesehatan Republik Indonesia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Strauss J, Witoelar F, Sikoki B, et al. . 2009. The 4th Wave of the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS4): overview and field report. Working paper No: WR-675/1-NIA/NICHD.

- 31. Burki T. Cancer and cultural differences. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:1125–6. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70286-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Olken BA, Onishi J, Wong S. Indonesia’s PNPM Generasi program: final impact evaluation report. Washington DC, USA: World Bank, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eggleston K, Bir A. Physician dual practice. Health Policy 2006;78:157–66. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jan S, Bian Y, Jumpa M, et al. . Dual job holding by public sector health professionals in highly resource-constrained settings: problem or solution? Bull World Health Organ 2005;83:771–6. doi:/S0042-96862005001000014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wagstaff A, Cotlear D, Eozenou PH-V, et al. . Measuring progress towards universal health coverage: with an application to 24 developing countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 2016;32:147–89. 10.1093/oxrep/grv019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heywood PF, Harahap NP. Human resources for health at the district level in Indonesia: the smoke and mirrors of decentralization. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:6 10.1186/1478-4491-7-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barber SL, Gertler PJ, Harimurti P. Differences in access to high-quality outpatient care in Indonesia. Health Aff 2007;26:w352–66. 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.w352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moreno-Serra R, Smith PC. Does progress towards universal health coverage improve population health? Lancet 2012;380:917–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61039-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.