Abstract

Objective

To investigate sex differences in survival of primary care treated patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) in the Netherlands.

Setting

Primary care.

Participants

A total of 1815 patients who participated in a prospective observational cohort study (Zwolle Outpatient Diabetes Project Integrating Available Care (ZODIAC)) were included of which 56% was female. Inclusion took place in 1998, 1999 and 2001. Vital status was assessed in 2013.

Main outcome measure

Relative survival of men and women with T2D. The relative survival rate was expressed as the ratio of observed survival of patients divided by the survival of the general population in the Netherlands with comparable age.

Results

After 14 years, 888 (49%) patients had died. The relative survival rate was 0.88 (0.81–0.94) for men and 0.82 (0.76–0.87) for women with T2D after 14 years (p value for difference between sexes=0.169). In patients without a history of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), the relative survival was 0.99 (0.94–1.05) in men and 0.92 (0.87–0.97) in women (p value for difference between sexes=0.046).

Conclusions

The survival of men and women with T2D was 12% and 18% lower, respectively, after 14 years of follow-up compared with men and women in the general population. This corresponds to a decrease in median survival of 2.2 and 3.5 years in men and women, respectively. Only for patients with T2D without a history of CVD, a significantly lower relative survival in women compared with men with T2D was found.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, sex differences, relative survival

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides insight in the current situation concerning the survival of men and women with type 2 diabetes who are treated in primary care in the Netherlands.

This study used the technique of relative survival analysis, hereby a comparison between the survival of patients with type 2 diabetes and the expected survival of whole general population could be made.

The survival rates of men and women in the general population were derived from mortality rates of the entire nation.

The generalisability is limited to primary care.

No data were known concerning clinical variables in the general population, and therefore the results of the subgroups should be interpreted with caution.

Introduction

Mortality rates in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) are higher compared with the general population, which is predominantly caused by a higher occurrence of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in patients with T2D.1–3 This excess mortality rate is described to be more pronounced in women compared with men with T2D.2–5 In a recent meta-analysis, the relative risk for mortality of incident coronary heart disease was 2.8 in women and 2.0 in men compared with men and women without diabetes, respectively.2

Current knowledge on sex differences in mortality is mostly based on older cohort studies. Whether these results are still reflecting current practice is less clear, as the care for patients with T2D has significantly improved over the last years.6 In the Netherlands, most patients with T2D receive protocol-based treatment exclusively in primary care. The mortality in this population is low, which is probably the result of a general improvement in quality of diabetes care over the last years.7 It is less well established whether sex differences in mortality also exist in well-controlled primary care patients. Only a few studies have been recently conducted in countries with a comparable care system to the Netherlands.8–10 A study from Norway also described a more pronounced excess mortality rate in women with T2D; however, this study also included secondary care treated patients.10 A retrospective study from the UK in primary care found only a slightly higher HR for all-cause mortality in women than in men with T2D, when compared with non-diabetics.8

The aim of this study was to investigate the survival of prospectively followed men and women with T2D, treated in primary care, compared with men and women in the general population.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

The study population consisted of patients who were included in the Zwolle Outpatient Diabetes Project Integrating Available Care (ZODIAC) study. This study was initiated in 1998, in the Zwolle region of the Netherlands. The design and details of this study have been published previously.11 In this study, general practitioners were assisted by hospital-based diabetes specialist nurses in their care of patients with T2D. In the first year, 1143 patients with T2D were included in this prospective cohort study. Another 127 and 545 patients with T2D entered this study in 1999 and 2001 respectively, resulting in a combined cohort of 1815 patients. All patients with T2D were selected from general practices in Zwolle region of the Netherlands. Patients with a very short life expectancy or insufficient cognitive capabilities were excluded from participation as the care for these patients has not been delegated to diabetes specialist nurses. Whether the life expectancy was long enough to be included in the ZODIAC study was based on the judgement of the general practitioners.

The survival of this cohort was compared with the expected survival of men and women with the same age from the general population in the Netherlands. These expected survival rates were derived from data provided by Statistics Netherlands. This organisation provides survival rates for men and women of every age in the Netherlands.12

This study was approved by the local ethical committee of Isala, Zwolle, the Netherlands. All patients gave written informed consent.

Data collection and measurements

Before participating in the ZODIAC study, T2D was already diagnosed in all individuals by their general practitioners based on the guidelines of the Dutch College of General Practitioners (two times a fasting plasma glucose level ≥7 mmol/L or one time a non-fasting plasma glucose level ≥11.1 mmol/L accompanied by symptoms of hyperglycaemia).13

Information on CVD, smoking and medication use was collected during the check-up of the patient by the general practitioner or practice nurse at baseline of the study. Patients were considered to have a history of CVD if a history of angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass grafting, stroke or a transient ischaemic attack was documented in the patient record of the general practice. Data on heart failure were not collected as these were not properly documented at baseline. Smoking was included in the analyses as a categorical variable (yes/no). Laboratory and physical assessment data were collected at baseline during the annual check-up of the patients by their general practitioner and practice nurse and included non-fasting lipid profile, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), serum creatinine, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), blood pressure and information about neuropathy and diabetic retinopathy. ACR was measured using immunonephelometry (Behring Nephelometer, Mannheim, Germany), and blood pressure was measured twice with a Welch Allyn sphygmomanometer in the supine position after at least 5 min of rest. Foot sensibility was tested with 5.07 Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments. Neuropathy was defined as two or more errors in a test of three, at least at one foot. Diabetic retinopathy (DRP) was investigated with a retinal camera, and the fundus photos were judged by an ophthalmologist. Microalbuminuria was defined as an albumin-to-creatinine ratio between 3.5 and 35 mg/mmol for women and between 2.5 and 25 mg/mmol for men. Macroalbuminuria was defined as an albumin-to-creatinine ratio >35 mg/mmol for women and >25 mg/mmol for men. The same methods were used in each baseline year to measure the laboratory and physical assessment data.

Clinical endpoints

The primary endpoint was the relative survival rate of men and women with T2D compared with the general population in the Netherlands. Secondary endpoints were the relative survival rates of patients with T2D in different subgroups, and the median survival of men and women. Subgroups for the relative survival analyses were defined for age (<60, 60–75 and >75 years), body mass index (BMI) (<25, 25–30 and >30 kg/m2), smoking, history of CVD, albuminuria (normoalbuminuria, microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria), microvascular complications (defined as the presence of albuminuria, neuropathy or DRP) and for patients with a low CVD risk (defined as non-smoking patients without a history of CVD and microvascular complications). In 2013, vital status and cause of death of patients with T2D were retrieved from records maintained by the hospital and the general practitioners or from the nationwide Municipal Personal Records Database. Causes of death were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9). Cardiovascular death was defined as death in which the principal cause of death was cardiovascular in nature, using ICD-9 codes 390–459.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.20.0 for Windows (SPSS) and Stata 14 (Stata). Baseline results were expressed as mean with SD or median with IQR for normally distributed and non-normally distributed data, respectively. Differences were considered to be significant at a p value of <0.05. Survival was calculated using relative survival analysis.14 The relative survival rate was calculated by measuring the ratio of survival of patients observed in our ZODIAC cohort to the survival of men and women with corresponding age in the same baseline year in the general population in the Netherlands. First, interval-specific and cumulative survival rates were measured for both the study population and the general population, using the Hakulinen method.15 The interval-specific observed survival rate for each follow-up year of the study population was calculated based on the number of patients at risk, the number of deaths and the number of patients lost to follow-up in each year. The interval-specific expected survival rate for the general population was calculated using yearly specific survival data of the general population.12 Consequently, the cumulative survival rate was measured for both the study group and the general population. Finally, the relative cumulative survival rate was calculated. The relative cumulative survival rate for the total study population is described for each of the 14 follow-up years for men and women separately. To investigate whether the relative survival was significant different between sexes, the p value was calculated at 14 years of follow-up. For the subgroup analyses, the relative cumulative survival rate is only described after 10 years of follow-up. Cumulative survival rates after 10 years are described due to the fact that 14-year survival data were only available for patients who were included in 1998. The relative cumulative survival rates after 10 years are therefore more reliable. p Values for the differences between sexes were calculated at 10 years of follow-up for the subgroup analyses. An estimation of the median survival of the study population was calculated using linear interpolation. For the general population, linear extrapolation with the average difference between the cumulative survivals of the general population was conducted first, before using linear interpolation to estimate the median survival (see online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2017-015870supp001.pdf (114.8KB, pdf)

Results

Baseline results of the study population are described in table 1. Fifty-six per cent of the patients were female. Mean age was 65.0 (11.8) years in men and 68.6 (11.6) years in women. The median diabetes duration was 4.0 (1.8–9.0) and 5.0 (2.0–10.0) years in men and women, respectively. Men smoked more frequently and also had more often albuminuria and a previous history of CVD compared with women. Women had a higher systolic blood pressure, a higher BMI and more often diabetic retinopathy than men. Men were more often on diet treatment only while women were more often on insulin. Lipid-lowering drugs and antiplatelet drugs were more often used in men.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Total (n=1815) | Men (n=800) | Women (n=1015) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 67.0 (±11.8) | 65.0 (±11.8) | 68.6 (±11.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 4.0 (2.0–9.0) | 4.0 (1.8–9.0) | 5.0 (2.0–10.0) | 0.017 |

| History of CVD | 605 (33.3) | 307 (38.4) | 298 (29.4) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 342 (19.0) | 206 (26.0) | 136 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.1 (±4.8) | 28.2 (±4.1) | 29.9 (±5.2) | <0.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 151.5 (±24.4) | 147.2 (±23.4) | 155.0 (±24.5) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 7.0 (6.3–8.1) | 6.9 (6.2–8.1) | 7.1 (6.4–8.1) | 0.131 |

| Creatine (µmol/L) | 92.0 (82.0–104.0) | 98.0 (89.0–109.0) | 86.0 (77.0–97.0) | <0.001 |

| Chol-HDL ratio | 4.8 (3.9–5.9) | 4.9 (4.0–6.0) | 4.7 (3.8–5.8) | 0.001 |

| Retinopathy | 190 (10.9) | 70 (9.1) | 120 (12.3) | 0.030 |

| Microalbuminuria | 544 (30.8) | 267 (34.0) | 277 (28.3) | 0.011 |

| Macroalbuminuria | 114 (6.5) | 68 (8.7) | 46 (4.7) | 0.001 |

| Neuropathy | 477 (26.6) | 212 (26.7) | 265 (26.6) | 0.931 |

| Microvascular complications* | 1012 (57.7) | 466 (59.7) | 546 (56.1) | 0.120 |

| Low CVD risk† | 424 (23.4) | 154 (19.3) | 270 (26.6) | <0.001 |

| DM treatment | ||||

| Diet | 318 (17.5) | 158 (19.8) | 160 (15.8) | 0.026 |

| Oral only | 1230 (67.8) | 540 (67.6) | 690 (68.0) | 0.834 |

| Insulin | 262 (14.5) | 99 (12.4) | 163 (16.1) | 0.028 |

| ACEi/ARB | 433 (27.1) | 179 (25.1) | 254 (28.7) | 0.108 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 278 (15.6) | 139 (17.7) | 139 (13.9) | 0.030 |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 279 (15.6) | 139 (17.6) | 140 (14.0) | 0.035 |

| Death | 888 (48.9) | 381 (47.6) | 507 (50.0) | 0.325 |

| CVD death | 374 (20.6) | 161 (20.1) | 213 (21.0) | 0.653 |

Values are depicted as n (%), mean (±SD) or median (IQR).

*Defined as the presence of albuminuria, neuropathy or DRP.

†Defined as non-smoking patients without a history of CVD and microvascular complications.

ACEi, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.; BMI, body mass index; Chol-HDL, cholesterol-High Density Lipoprotein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; DRP, diabetic retinopathy; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Relative survival analyses

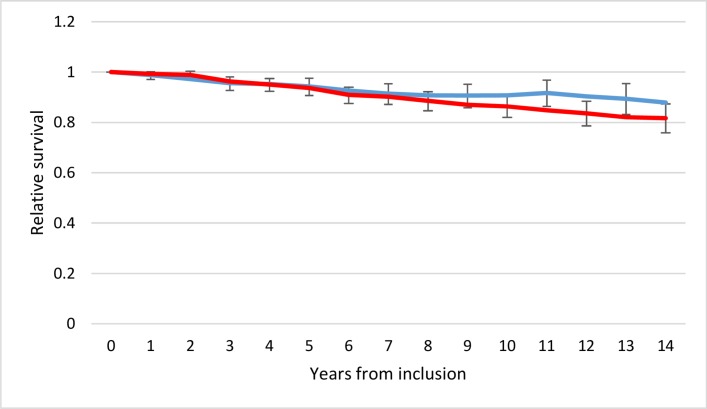

The incidence rate for all-cause mortality was 7.4 (6.7–8.2) and 7.2 (6.5–7.8) per 100 person years in men and women with T2D, respectively. The incidence rate for CVD mortality was 3.1 (2.7–3.6) and 3.0 (2.6–3.4) per 100 person years in men and women with T2D, respectively. The comparison between the survival of the patients with T2D and the general population is presented in table 2 and figure 1 for men and women separately. After 14 years, the relative survival rate was 0.88 (95%CI: 0.81 to 0.94) for men and 0.82 (95%CI: 0.76 to 0.87) for women with T2D (p value for difference between sexes=0.169). The estimated median survival of men (mean age: 65.0) and women (mean age: 68.8) in the study population was 13.8 and 13.0 years, respectively. In the general population, the estimated median survival of men and women was 16.0 and 16.5 years respectively

Table 2.

Relative survival for men and women with type 2 diabetes compared with men and women with the same age from the general population

| Men | Women | |||||||||||

| Follow-up | N | Death | Lost to follow-up | COS | CES | Relative cumulative survival | N | Death | Lost to follow-up | COS | CES | Relative cumulative survival |

| 0–1 | 800 | 36 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 1015 | 35 | 2 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) |

| 1–2 | 763 | 38 | 0 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 978 | 32 | 0 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) |

| 2–3 | 725 | 38 | 0 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | 946 | 53 | 0 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) |

| 3–4 | 687 | 28 | 1 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.95 (0.92–0.98) | 893 | 40 | 2 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) |

| 4–5 | 658 | 31 | 0 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.94 (0.91–0.98) | 851 | 41 | 0 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) |

| 5–6 | 627 | 35 | 1 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.93 (0.89–0.96) | 810 | 52 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) |

| 6–7 | 591 | 30 | 3 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.91 (0.87–0.95) | 754 | 33 | 6 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.90 (0.87–0.94) |

| 7–8 | 558 | 26 | 1 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.91 (0.86–0.95) | 715 | 40 | 0 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.89 (0.85–0.92) |

| 8–9 | 531 | 22 | 0 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.91 (0.86–0.95) | 675 | 38 | 3 | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.87 (0.83–0.91) |

| 9–10 | 509 | 20 | 0 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.91 (0.86–0.96) | 634 | 30 | 0 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.86 (0.82–0.91) |

| 10–11 | 489 | 15 | 58 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.92 (0.86–0.97) | 604 | 35 | 62 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.85 (0.80–0.89) |

| 11–12 | 416 | 22 | 101 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) | 507 | 28 | 93 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.84 (0.79–0.88) |

| 12–13 | 293 | 17 | 3 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) | 386 | 26 | 4 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.82 (0.77–0.88) |

| 13–14 | 273 | 16 | 60 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.88 (0.81–0.94) | 356 | 18 | 97 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.82 (0.76–0.87) |

CES, cumulative expected survival.; COS, cumulative observed survival; N, number of patients at risk.

Figure 1.

Relative survival with 95% CI for men and women with type 2 diabetes. Men: blue line, women: red line.

Subgroup analyses

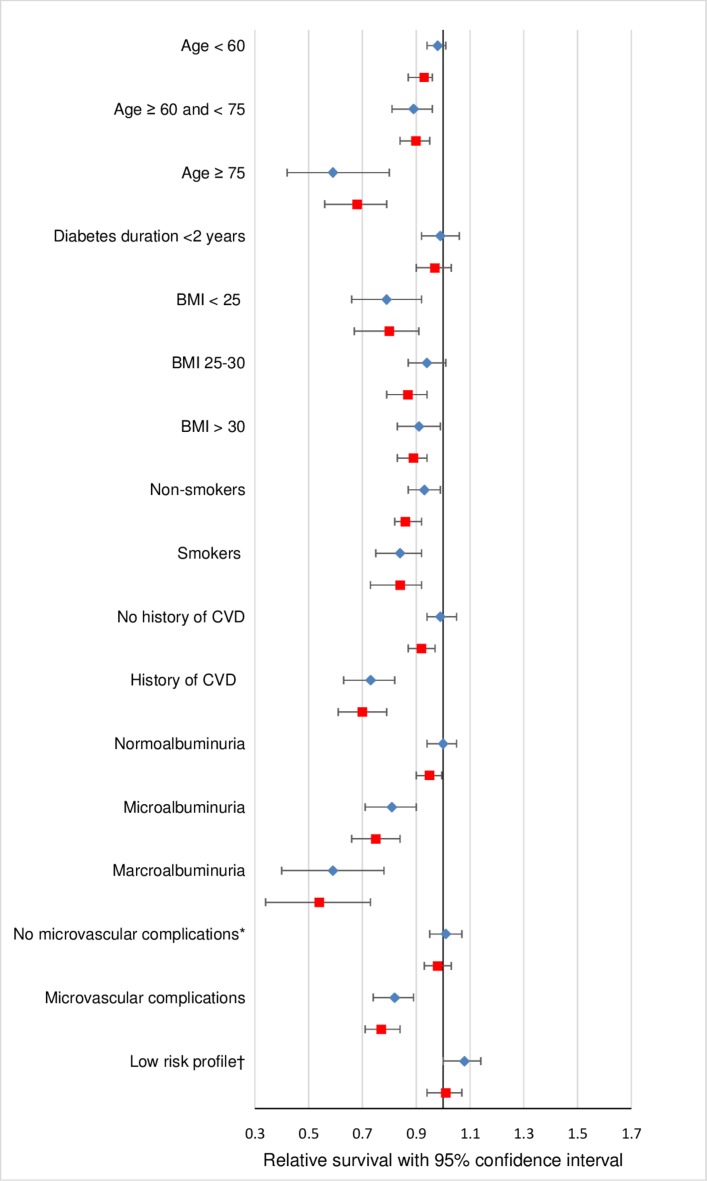

The relative survival rate after 10 years for different subgroups is described in table 3 and figure 2 for men and women separately. In the subgroup of patients with T2D without microvascular complications, the relative survival rate of men and women with T2D was 1.01 (95%CI: 0.95 to 1.07) and 0.98 (95%CI: 0.93 to 1.03), respectively (p=0.488). In patients with microvascular complications, the relative survival rate decreased to 0.82 (95%CI: 0.74 to 0.89) for men and 0.77 (95%CI: 0.71 to 0.84) for women with T2D (p=0.395). In men and women with low CVD risk (defined as non-smoking patients without a history of CVD and microvascular complications) the relative survival rate was 1.08 (95%CI: 1.00 to 1.14) and 1.01 (0.94–1.07), respectively (p=0.106). The relative survival rates of men<60 years, of men with a BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2, of men without a history of CVD and of men without albuminuria were not significantly different from men in the general population. The relative survival rate in women in all these categories was significantly lower compared with women in the general population. For patients without a history of CVD, the relative survival was significantly lower in women with T2D compared with men (p=0.046).

Table 3.

Relative survival after 10 years for different subgroups

| Men | Women | ||||||||

| Category | N | Death | Lost to follow-up | Relative survival (95% CI) | N | Death | Lost to follow-up | Relative survival (95% CI) | p Value* |

| Age<60 | 276 | 24 | 3 | 0.98 (0.94 to 1.01) | 224 | 26 | 4 | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.96) | 0.052 |

| Age≥60 and<75 | 337 | 126 | 3 | 0.89 (0.81 to 0.96) | 448 | 123 | 5 | 0.89 (0.84 to 0.95) | 0.870 |

| Age≥75 | 187 | 154 | 1 | 0.59 (0.42 to 0.80) | 343 | 245 | 8 | 0.68 (0.56 to 0.79) | 0.909 |

| Diabetes duration<2 years | 206 | 76 | 1 | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) | 232 | 83 | 5 | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.03) | 0.626 |

| BMI<25 | 174 | 96 | 1 | 0.79 (0.66 to 0.92) | 169 | 83 | 4 | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.91) | 0.914 |

| BMI 25–30 | 392 | 135 | 4 | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.01) | 377 | 153 | 6 | 0.87 (0.79 to 0.94) | 0.126 |

| BMI>30 | 232 | 73 | 2 | 0.91 (0.83 to 0.99) | 465 | 154 | 7 | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.94) | 0.616 |

| Non-smokers | 583 | 226 | 5 | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | 869 | 349 | 14 | 0.86 (0.82 to 0.92) | 0.121 |

| Smokers | 206 | 76 | 2 | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.92) | 136 | 40 | 3 | 0.84 (0.73 to 0.92) | 0.931 |

| No history of CVD | 492 | 132 | 3 | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.05) | 717 | 228 | 11 | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.97) | 0.046 |

| History of CVD | 306 | 172 | 4 | 0.73 (0.63 to 0.82) | 298 | 166 | 6 | 0.70 (0.61 to 0.79) | 0.648 |

| Normoalbuminuria | 450 | 116 | 3 | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.05) | 655 | 198 | 11 | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) | 0.214 |

| Microalbuminuria | 266 | 134 | 3 | 0.81 (0.71 to 0.90) | 277 | 138 | 5 | 0.75 (0.66 to 0.84) | 0.444 |

| Macroalbuminuria | 68 | 45 | 1 | 0.59 (0.40 to 0.78) | 46 | 28 | 1 | 0.54 (0.34 to 0.73) | 0.886 |

| No microvascular complications | 314 | 70 | 1 | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.07) | 428 | 104 | 5 | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.03) | 0.488 |

| Microvascular complications† | 464 | 227 | 5 | 0.82 (0.74 to 0.89) | 546 | 263 | 10 | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.84) | 0.395 |

| Low-risk profile‡ | 154 | 21 | 1 | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.14) | 270 | 58 | 4 | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.07) | 0.106 |

*Difference between men and women.

†Defined as the presence of albuminuria, neuropathy or DRP.

‡Defined as non-smoking patients without a history of CVD and microvascular complications.

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DRP, diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 2.

Relative survival with 95% CI for men and women with type 2 diabetes after 10 years in different subgroups. Men: blue diamond, women: red square. BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease. *Defined as the absence of albuminuria, neuropathy and diabetic retinopathy; †defined as non-smoking patients without a history of CVD and microvascular complications.

Discussion

In primary care treated patients with T2D, the relative survival of men and women was 12% and 18% lower after 14 years of follow-up compared with age-matched men and women in the general population, respectively. This translates into an overall decrease in median survival of 2.2 years in men and 3.5 years in women with T2D compared with men and women in the general population. Although the relative survival of women with T2D seems to be lower than in male counterparts, no significant difference between sexes was found in the total study population. The survival rate in certain subgroups of men with T2D (young age, no albuminuria, no history of CVD, BMI 25–30) was comparable to the survival rate of men in the general population. In women, in these subgroups the relative survival was significantly lower compared with women without T2D. Only for patients with T2D without a history of CVD a significantly lower relative survival in women compared with men with T2D was found.

The differences in relative survival between men and women in the total study population could possibly be explained by both the higher age and longer diabetes duration in women with T2D. Although women have a lower relative survival, it is not significantly lower compared with men. When women would have the same age and the same diabetes duration as men, the difference in relative survival would likely be smaller. This strengthens our conclusion that in the total population there is no significant difference in relative survival between sexes. Many studies have described a higher excess mortality rate in women than in men with T2D.4 5 16 In our study, a higher impact of T2D in women was only found in the subgroup of patients without a history of CVD. In subgroups of patients<60 years of age, without albuminuria and with a BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2, the relative survival of women with T2D was lower compared with women in the general population but not lower compared with the relative survival of men with T2D. The comparable survival of men with T2D without a history of CVD to men in the general population has partly been described before by Kalyani et al.17 In a population without ischaemic heart disease, they found an increased risk for the combined outcome of ischaemic heart disease and mortality in women with diabetes compared with women without diabetes whereas they found no differences in men.

The decrease in median survival which is found in our study seems to be smaller than those seen in previous studies. Results from the Framingham Heart Study showed that men and women with diabetes lived on average 7.5 (95% CI: 5.5 to 9.5) and 8.2 (95% CI: 6.1 to 10.4) years less compared with men and women without diabetes. However, this cohort started between 1948 and 1951 when treatment options for T2D were limited. In a more recent study from Canada, for both men and women at the age of 55 on average 5.0 (95% CI: 4.9 to 5.1) and 6.0 (95% CI: 5.9 to 6.1) years lower life expectancy was estimated compared with men and women without diabetes.18 Although patient characteristics differ between studies and various methods were used to measure survival, it may indicate that the loss of life years due to diabetes is decreasing in both men and women.

Although different theories have been described which may explain the observed sex difference in the impact of diabetes on survival, it is still not completely understood. Undertreatment of women with T2D is mentioned as a possible explaining factor. A lower prescription percentage for aspirin and lipid-lowering drugs was found in women compared with men with T2D.19 However, in a recent study in primary care we did not find significant sex differences in these prescribed medications.20 The sex difference in survival may also be explained by a greater excess in cardiovascular risk factors between women with and without T2D compared with their male counterparts.4 21 This greater excess in risk factors is probably the result of a more favourable risk factor profile and a lower insulin resistance in women without diabetes compared with men.21 22 Although the relatively higher risk for women with T2D for fatal ischaemic heart disease remained significant in various meta-analyses after adjustment for other cardiovascular risk factors, it may still be an explanation as only traditional risk factors were taken into account.2 4 The lower relative survival could also be a result of a higher prevalence of obesity in women with T2D. In the Netherlands, the prevalence of obesity is described to be 25% to 50% higher in women compared with men with T2D, whereas the prevalence of overweight is 20% to 35% higher in men compared with women in different age categories.20 Knowing that overweight is associated with a lower mortality risk and obesity with a higher mortality risk compared with patient with a normal weight, this could possibly be one of the explaining factors for the higher relative mortality rate in women with T2D.23 Finally, the relative higher mortality in women with T2D may be a result of underdiagnosis of ischaemic heart disease in women. Women with T2D have less obstructive coronary disease compared with men, with higher rates of microvascular coronary dysfunction that may be more difficult to diagnose and treat.24 Also, a higher prevalence of undiagnosed heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is described in women compared with men with T2D.25 When focusing on the common symptoms and diagnostic criteria for ischaemic heart disease and HFpEF, these diagnoses could be easily missed in women. This may lead to undertreatment of women, resulting in a higher mortality when having T2D.

Some limitations should be mentioned. First, according to Hakulinen, relative survival is the ratio of the observed survival in a group of patients to the expected survival in a group of individuals in the general population, who are comparable with the patients concerning all possible factors affecting survival, except for the disease of interest.15 Our choice to compare survival of patients with T2D from the Zwolle region with the general population can therefore be criticised. However, the underlying assumption by the use of the expected survivals of the general population is that the deaths directly due to T2D are a negligible proportion of all deaths in the general population. Second, although no specific indications exist which suggests that people in the Zwolle region are healthier or unhealthier compared with the whole population in the Netherlands, we do not now that for sure. It would have been better if we had used a control population from the Zwolle region, but unfortunately such a control population was not available. Third, no data were known concerning clinical variables in the general population, as we did not used a specific control group but expected survival rates which were derived from mortality rates of the entire nation. Therefore, the results of the subgroups should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, the number of patients in subgroups was sometimes relatively low which has decreased the precision of the estimates. Fifth, selection bias has occurred in this study. The study population consisted only of patients with T2D who are treated in primary care. Patients in secondary care often have worse manifestations of T2D and more often macrovascular disease and will probably have a lower survival. Furthermore, patients with a very short life expectancy or insufficient cognitive capabilities were also excluded from participation. Although these limitations imply that the generalisability of our results is limited to primary care, it is still representative for a large part of the T2D population due to the fact that the majority (>85%) of the patients with T2D are treated in primary care in the Netherlands.26 In this group of patients with T2D, the survival is only 2.2 years lower in men and 3.5 years lower in women compared with men and women in the general population. In patients with T2D with no microvascular complication and in patients with a low-risk profile, even no difference in survival compared with the general population was found.

In conclusion, the relative survival in men and women with T2D compared with the general population was 12% and 18% lower, respectively. The results of this study further show that survival in subgroups of men (ie, younger men, no albuminuria, no history CVD, BMI between 25 and 30) is comparable to men in the general population, while the survival in women in these subgroups is still lower compared with women in the general population. Only in women with T2D without a history of CVD, the impact of diabetes on survival is higher compared with men with T2D.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SHH, KJJH, KHG, HJGB and NK designed the study. SHH, KJJH and GWDL acquired the data. SHH, KJJH and KHG analysed the data. SHH, KJJH, KHG, GWDL, AHEMM, HJGB and NK interpreted the data. SHH and KJJH drafted the manuscript. KHG, GWDL, AHEMM, HJGB and NK reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the local ethical committee of Isala, Zwolle, the Netherlands. All patients gave written informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Barnett KN, Ogston SA, McMurdo ME, et al. A 12-year follow-up study of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among 10,532 people newly diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes in Tayside, Scotland. Diabet Med 2010;27:1124–9. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03075.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts including 858,507 individuals and 28,203 coronary events. Diabetologia 2014;57:1542–51. 10.1007/s00125-014-3260-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roche MM, Wang PP. Sex differences in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, hospitalization for individuals with and without diabetes, and patients with diabetes diagnosed early and late. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2582–90. 10.2337/dc12-1272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huxley R, Barzi F, Woodward M. Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2006;332:73–8. 10.1136/bmj.38678.389583.7C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee WL, Cheung AM, Cape D, et al. Impact of diabetes on coronary artery disease in women and men: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 2000;23:962–8. 10.2337/diacare.23.7.962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Hateren KJ, Drion I, Kleefstra N, et al. A prospective observational study of quality of diabetes care in a shared care setting: trends and age differences (ZODIAC-19). BMJ Open 2012;2:e001387 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lutgers HL, Gerrits EG, Sluiter WJ, et al. Life expectancy in a large cohort of type 2 diabetes patients treated in primary care (ZODIAC-10). PLoS One 2009;4:e6817 10.1371/journal.pone.0006817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liang H, Vallarino C, Joseph G, et al. Increased risk of subsequent myocardial infarction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study using the U.K. General Practice Research Database. Diabetes Care 2014;37:1329–37. 10.2337/dc13-1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hyvärinen M, Tuomilehto J, Laatikainen T, et al. The impact of diabetes on coronary heart disease differs from that on ischaemic stroke with regard to the gender. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2009;8:17 10.1186/1475-2840-8-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Madssen E, Vatten L, Nilsen TI, et al. Abnormal glucose regulation and gender-specific risk of fatal coronary artery disease in the HUNT 1 study. Scand Cardiovasc J 2012;46:219–25. 10.3109/14017431.2012.664646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ubink-Veltmaat LJ, Bilo HJ, Groenier KH, et al. Shared care with task delegation to nurses for type 2 diabetes: prospective observational study. Neth J Med 2005;63:103–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Data published by Statistics Netherlands. Dutch: “‘Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek’”[Internet]. http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/selection/?DM=SLNL&PA=70701NED&VW=T.

- 13. Rutten G, Verhoeven S, Heine RJ, et al. NHG-standaard diabetes mellitus type 2. Eerste herziening. Huisarts Wet 1999;42:67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hockey R, Tooth L, Dobson A. Relative survival: a useful tool to assess generalisability in longitudinal studies of health in older persons. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2011;8:3 10.1186/1742-7622-8-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hakulinen T. Cancer survival corrected for heterogeneity in patient withdrawal. Biometrics 1982;38:933–42. 10.2307/2529873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanaya AM, Grady D, Barrett-Connor E. Explaining the sex difference in coronary heart disease mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1737–45. 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kalyani RR, Lazo M, Ouyang P, et al. Sex differences in diabetes and risk of incident coronary artery disease in healthy young and middle-aged adults. Diabetes Care 2014;37:830–8. 10.2337/dc13-1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loukine L, Waters C, Choi BC, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on life expectancy and health-adjusted life expectancy in Canada. Popul Health Metr 2012;10:7 10.1186/1478-7954-10-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Meigs JB, et al. Sex disparities in treatment of cardiac risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:514–20. 10.2337/diacare.28.3.514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hendriks SH, van Hateren KJ, Groenier KH, et al. Sex differences in the quality of diabetes care in the Netherlands (ZODIAC-45). PLoS One 2015;10:e0145907 10.1371/journal.pone.0145907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wannamethee SG, Papacosta O, Lawlor DA, et al. Do women exhibit greater differences in established and novel risk factors between diabetes and non-diabetes than men? The British Regional Heart Study and British Women’s Heart Health Study. Diabetologia 2012;55:80–7. 10.1007/s00125-011-2284-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Orchard TJ, Becker DJ, Kuller LH, et al. Age and sex variations in glucose tolerance and insulin responses: parallels with cardiovascular risk. J Chronic Dis 1982;35:123–32. 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90113-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, et al. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013;309:71–82. 10.1001/jama.2012.113905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tamis-Holland JE, Lu J, Korytkowski M, et al. Sex differences in presentation and outcome among patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease treated with contemporary medical therapy with or without prompt revascularization: a report from the BARI 2D Trial (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1767–76. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boonman-de Winter LJ, Rutten FH, Cramer MJ, et al. High prevalence of previously unknown heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2012;55:2154–62. 10.1007/s00125-012-2579-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. InEen. 2014. In Dutch: Transparante ketenzorg diabetes mellitus, COPD en VRM raportage zorggroepen over 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-015870supp001.pdf (114.8KB, pdf)