Abstract

Objectives

We investigated whether biopsychosocial and spiritual factors and satisfaction with care were associated with patients’ perceived quality of life.

Design

This was a cross-sectional analytical study.

Setting

Data were collected from inpatients at a postacute geriatric rehabilitation centre in a university hospital in Switzerland.

Participants

Participants aged 65 years and over were consecutively recruited from October 2014 to January 2016. Exclusion criteria included significant cognitive disorder and terminal illness. Of 227 eligible participants, complete data were collected from 167.

Main outcome measures

Perceived quality of life was measured using WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire—version for older people. Predictive factors were age, sex, functional status at admission, comorbidities, cognitive status, depressive symptoms, living conditions and satisfaction with care. A secondary focus was the association between spiritual needs and quality of life.

Results

Patients undergoing geriatric rehabilitation experienced a good quality of life. Greater quality of life was significantly associated with higher functional status (rs=0.204, p=0.011), better cognitive status (rs=0.175, p=0.029) and greater satisfaction with care (rs=0.264, p=0.003). Poorer quality of life was significantly associated with comorbidities (rs=−.226, p=0.033), greater depressive symptoms (rs=−.379, p<0.001) and unmet spiritual needs (rs=−.211, p=0.049). Multivariate linear regression indicated that depressive symptoms (β=−0.961; 95% CIs −1.449 to 0.472; p<0.001) significantly predicted quality of life.

Conclusions

Patient perceptions of quality of life were significantly associated with depression. More research is needed to assess whether considering quality of life could improve care plan creation.

Keywords: geriatric medicine, geriatric rehabilitation, quality of life, biopsychosocial and spiritual model, satisfaction with care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study uses biopsychosocial and spiritual descriptors to explore determinants of quality of life in geriatric rehabilitation.

Design is based on a ‘real world’ setting, with usual clinical practice descriptors of biopsychosocial and spiritual dimensions, which is likely to result in good ecological validity.

Owing to the precedent point, the rate of missing values is higher, which may induce a bias. To address this, the multivariate analysis included multiple imputation.

All evaluations were not made at the same time, and we cannot exclude the possibility that symptomatic change may have occurred in some patients.

Introduction

Quality of life is an increasingly interesting outcome in the context of the ageing population. It is relevant to consider quality of life rather than mortality in elderly people, given the high prevalence of chronic conditions and their impact on functional independence. Elderly people usually prefer quality of life over long life.1 It seems, therefore, valuable to study quality of life in elderly persons and to identify likely influential factors.

Overall, elderly community-dwelling populations retain a good quality of life. For instance, in a random sample of 999 English respondents over 65 years of age, 82% described their quality of life as good.2 Quality of life in elderly persons is affected by a variety of factors; thus, depressive disorders, functional impairment and other health problems could reduce a patient’s quality of life, whereas social support can positively affect quality of life.3 Psychosocial resources can have a substantial influence on quality of life, affecting situations such as, for example, facing a diminution of functionality.2 Although quality of life can decrease with physical impairment, elderly persons suffering significant limitations in their daily lives may nevertheless (and somewhat paradoxically) describe their quality of life as excellent.4 5 In a study of 185 community-dwelling older Americans with advanced illness, Solomon et al found that 65% of patients reported their quality of life as the best possible or good.6

Quality of life in elderly persons has been assessed in a number of healthcare settings (acute care, assisted living and nursing home). Existing studies have similar results, and tend to show that the perceived quality of life remains good in these settings.7 8 There are only a few studies that investigate quality of life in rehabilitation and most of them were focused on patients with very specific illnesses, such as osteoporosis and hip fracture.4 9 However, measuring quality of life in this setting should be of interest because improving quality of life is typically understood as the ultimate goal of rehabilitation.10 11 Moreover, it could be a broader outcome to measure in rehabilitation, in addition to traditional variables linked to functional independence improvement.

Geriatric rehabilitation is traditionally interdisciplinary, with attention paid to biopsychosocial issues.12 13 This setting even integrates the spiritual dimension at different levels, in a global biopsychosocial and spiritual model of care.14 15

The biopsychosocial and spiritual model is a representation of the human being in which the biological, psychological, social and spiritual dimensions are considered to be simultaneously in play.12 14 Sulmasy hypothesises that the biological, psychological, social and spiritual dimensions of this model contribute to quality of life: ‘the composite state—how the patient feels physically, how the patient is faring psychologically and interpersonally, as well as how the patient is progressing spiritually—constitutes the substrate of the construct called quality of life’.14

Thus, we aimed to examine the biopsychosocial and spiritual factors associated with quality of life in elderly hospitalised patients undergoing postacute rehabilitation.

Because this population is reliant on the hospital institution and is involved in constant interaction with healthcare providers, the patient’s perception of the treatment received has to be taken into account. Satisfaction with care is one proxy to describe the system from the perspective of the patient, and the literature has shown the influence of satisfaction with care on quality of life in other settings.16 17 Therefore, the inclusion of an evaluation of satisfaction with the care patients received is relevant.

The following hypotheses are made:

The four dimensions of the biopsychosocial and spiritual model and the patient’s satisfaction with the care received are likely associated with the quality of life of a person undergoing geriatric rehabilitation.

To confirm this hypothesis, the objectives of this study are to explore:

The quality of life perceived by the patient in a setting of postacute geriatric rehabilitation.

The relationship between the biopsychosocial dimensions of the patient and patients’ perceived quality of life. As a secondary focus, the relationship between the spiritual dimension and patients’ perceived quality of life.

The relationship between satisfaction with care received and patients’ perceived quality of life.

Methods

Context and population

This cross-sectional analytical study was conducted at a postacute rehabilitation centre for geriatric patients at Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland. Participants were consecutively included during a cumulative period of 13 months running from October 2014 to January 2016. The patients spent an average of 20.5 days in this 95-bed centre, after an acute-care hospital stay, and 74% of them then returned home.

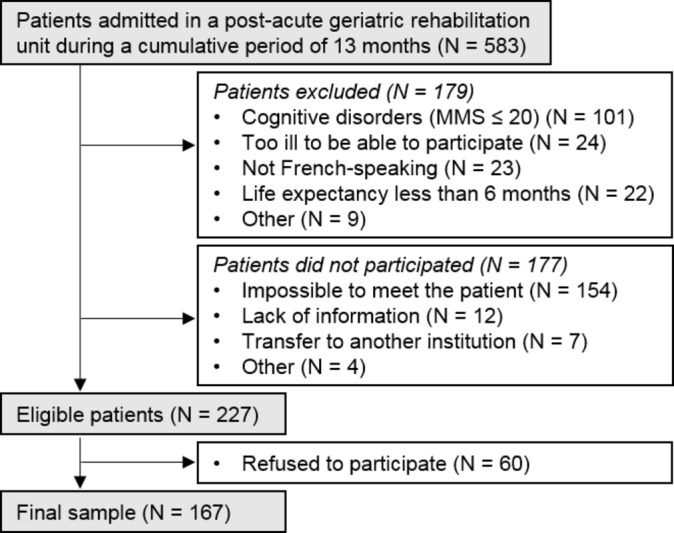

Eligible participants were at least 65 years old. Exclusion criteria included significant cognitive disorders (defined by a score of less than 21 on the Mini-Mental State, MMS18), too ill to be able to participate (medically unstable or with uncontrolled symptoms such as severe pain or significant dyspnoea), not French-speaking or a doctor-estimated life expectancy of less than 6 months. Patients who had previously been included and excluded were not reincluded as a case of new admission during this period. In the end, 167 patients participated in the study (figure 1). An analysis comparing the participants (n=167) with patients who refused to participate (n=60) and with those who did not participate owing to logistical reasons (n=177) did not show any characteristic significant differences.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. MMS, Mini-Mental State.

The study was approved by the Cantonal Committee of Vaud on the Ethics of Research on Human Subjects, and all the participants gave their written informed consent. The manuscript was drafted in accordance with the STROBE reporting guidelines (www.strobe-statement.org).

Data collected

At the time of admission, data were collected on age, sex, reason for admission, living conditions (living alone, use of home care services, living in a nursing home), functional status at home prior to admission (from history, using basic activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL); ADL scores ranged from 0 to 6,19 while IADL scores ranged from 0 to 8,20 a high score indicating better functional status), functional status at the time of admission to the geriatric rehabilitation centre (measured using the functional independence measure (FIM), with scores ranging from 18 to 126, a high score indicating better functional status),21 falls during the previous 12 months, cognitive status (measured using the MMS, with scores ranging from 0 to 30, a high score indicating better cognitive status)18 and level of comorbidities (measured using the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS), with scores ranging from 0 to 56, a high score indicating more comorbidities).22 During the second week of hospitalisation, a chaplain evaluated the spiritual needs of the patient (cf. below). All of these assessments were systematically conducted in the usual clinical setting.

Specifically for this research, a research assistant met with patients during their second week of hospitalisation at the postacute rehabilitation centre to evaluate their quality of life (cf. below), the presence of depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ9, with scores ranging from 0 to 27, a high score indicating more depressive symptoms)23 24 and their satisfaction with the care received (cf. below). The PHQ-9 was specifically chosen for its psychometric properties, as a usual clinical setting normally has a tool with lower properties.

WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire—version for older people (WHOQOL-OLD): Quality of life was evaluated by the WHOQOL-OLD, a questionnaire developed using WHO framework and translated into and validated in French.25 26 The WHOQOL-OLD is specifically intended for persons over 60 years of age and emphasises the following six dimensions, which are particularly relevant to the quality of life for this segment of the population: ‘sensory abilities’; ‘autonomy’; ‘past, present and future activities’; ‘social participation’; ‘death and dying’ and ‘intimacy’. The ‘sensory abilities’ dimension describes sensory functionality (hearing, sight, touch, taste and smell) and its impact on loss of quality of life. The ‘autonomy’ dimension involves the ability to maintain control over one’s actions and decisions. The ‘past, present and future activities’ dimension reflects the feeling of accomplishment during life and perspectives on life as it continues. The ‘social participation’ dimension assesses patient satisfaction related to his/her daily activities, particularly social activities. The ‘death and dying’ dimension refers to preoccupations with death. Finally, the ‘intimacy’ dimension relates to intimate and personal relations with persons who are close to the respondent. The questionnaire includes 24 answers evaluated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. The total score and the score for each dimension (which are calculated by an algorithm) range from 0 to 100. A high score indicates a higher quality of life.

Quality from the Patient’s Perspective Short Form (QPP-SF): The QPP-SF is a questionnaire that evaluates care using patient descriptions.27 28 It covers the following four areas: medical-technical competences (3 factors); physical–technical conditions (3 factors); identity-oriented approach (10 factors) and sociocultural atmosphere (4 factors). The final score ranges from 20 to 80; a high score indicates high satisfaction with the care received. For purposes of this study, the questionnaire was translated by two persons whose native language was French, and a native English speaker performed a reverse translation.

Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool (SDAT): The SDAT evaluates the spiritual needs of hospitalised elderly patients.29 30 The SDAT consists of five items (the need for life balance, the need for connection, the need for values acknowledgement, the need to maintain control and the need to maintain identity), scored on a Likert scale of 0 (need completely met) to 3 (need completely unmet). The total score ranges from 0 to 15; a high score indicates important unmet spiritual needs. The SDAT was administered to patients by a specially trained chaplain using a standardised procedure.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses of the variables were undertaken. Correlations of the different descriptive elements and quality of life were determined using Spearman rank correlations. Quality of life was considered both in overall terms and within each of its dimensions. Univariate analyses were carried out only with available data (complete case analysis), and the number of missing data was mentioned (see the Strengths and Weaknesses section for explanations about missing data). The data were analysed using Stata V.12.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX). Finally, a multivariate linear regression was undertaken, with the WHOQOL-OLD total as the dependent variable and age, sex, FIM, MMS, CIRS, PHQ-9, living conditions, SDAT and QPP-SF as explanatory variables. The number of participants required for the study was initially based on a rule of thumb of 10 times the number of coefficients, but this was then majored owing to missing values. Multicollinearity among the explanatory variables was assessed with the variance inflation factor. The residual variance was homogeneous, excluding any heteroscedasticity. No clear outliers emerged from the diagnostic plots. Parameters were estimated using multiple imputation (20 imputations), with R V.3.3.1 (www.r-project.org) and the package mice V.2.25.31 The number of missing values is also indicated. The statistical significance was set at p≤.050.

Results

Population description

The average age of the participants was 82.3±7.2 years and 65.9% were women. Their characteristics are described in table 1. The patients were mostly admitted from orthopaedics and traumatology (42%), internal medicine (41%), neurology (6%) and cardiovascular surgery (4%). Participants from orthopaedics and traumatology were admitted after fracture surgery (40%), elective surgery (39%), conservative treatment of fractures (17%) and other reasons (4%). From internal medicine, they were in postacute rehabilitation for gait and balance disorders of multifactorial aetiology (29%), an infectious disease (27%), a cardiac event (20%) and other reasons (25%).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patient sample

| Characteristics | No of missing values | Total sample (n=167) |

Women (n=110) |

Men (n=57) |

Orthopaedics and traumatology (n=70) |

Internal medicine (n=68) |

| Age (years) (mean±SD) | 0 | 82.3±7.2 | 82.5±7.5 | 81.8±6.7 | 80.7±7.5* | 84.3±6.6 |

| Women (%) | 0 | 65.9 | 100.0† | 0.0 | 74.3 | 60.3 |

| ADL index before admission‡ | 1 | 5.1±1.1 | 5.1±0.9 | 5.0±1.3 | 5.4±0.8* | 4.8±1.2 |

| IADL index before admission§ | 2 | 4.7±2.4 | 5.1±2.3† | 4.1±2.3 | 5.9±2.2* | 3.5±1.9 |

| Fall during the previous year (%) | 0 | 68.9 | 72.7 | 61.4 | 70.0 | 72.1 |

| Living alone (%) | 0 | 72.5 | 81.8† | 54.4 | 70.0 | 82.4 |

| Home care before hospitalisation (%) | 0 | 64.1 | 63.6 | 64.9 | 42.9* | 79.4 |

| Living in nursing home before hospitalisation (%) | 0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 |

| FIM¶ | 1 | 86.4±14.3 | 87.9±14.1† | 83.4±14.4 | 86.9±13.2 | 84.9±14.9 |

| MMS** | 0 | 26.7±2.7 | 26.7±2.8 | 26.8±2.7 | 27.2±2.7* | 26.1±2.8 |

| CIRS†† | 72 | 14.3±4.9 | 13.4±4.3† | 16.2±5.5 | 12.5±4.0* | 15.6±5.2 |

| PHQ-9‡‡ | 4 | 7.0±4.8 | 7.0±4.9 | 7.0±4.6 | 6.7±4.8 | 7.2±4.9 |

| SDAT§§ | 69 | 6.0±3.1 | 5.9±2.9 | 6.2±3.5 | 5.8±3.1 | 6.4±3.2 |

| QPP-SF¶¶ | 30 | 72.3±8.5 | 72.6±8.1 | 71.7±9.3 | 71.5±10.0 | 72.9±7.4 |

†Women versus men, p≤0.050.

*Orthopaedics and traumatology versus internal medicine, p≤0.050.

‡Activities of daily living (score range from min. 0 to max. 6).

§Instrumental activities of daily living (0 to 8).

¶Functional independence measure (18 to 126).

**Mini mental state (0 to 30).

††Cumulative illness rating scale (0 to 56).

‡‡Patient health questionnaire-9 (0 to 27).

§§Spiritual distress assessment tool (0 to 15).

¶¶Quality from the patient’s perspective short form (20 to 80).

Quality of life in geriatric rehabilitation

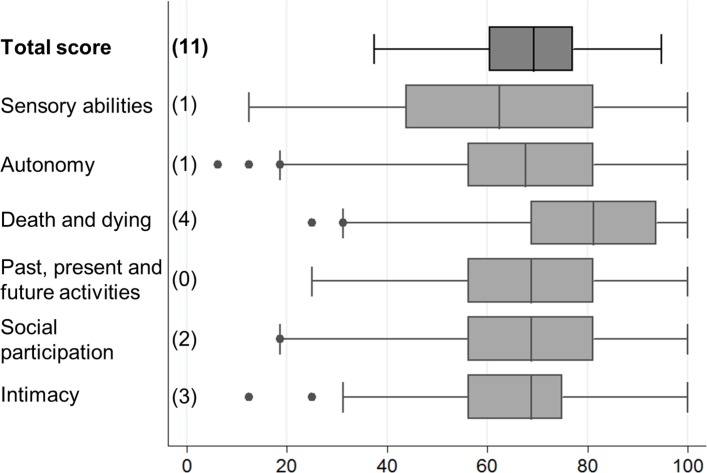

Overall, on a transformed scale of 0–100, the quality of life perceived by the patients is 68.3±12.2 (median 69.3, minimum 37.5, maximum 94.8) (figure 2). The dimensions of the WHOQOL-OLD range from 60.0±22.7 (‘sensory abilities’) to 77.4±18.8 (‘death and dying’).

Figure 2.

WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire—version for older people scores describing the overall quality of life and each underlying dimension. The number of missing values is indicated in parentheses.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with quality of life

Detailed data are provided in table 2. Overall better quality of life is significantly associated with a higher functional status at the time of entrance (FIM), a better cognitive state (MMS) and a better satisfaction regarding care received (QPP-SF). The presence of comorbidities (CIRS), lower mood (PHQ-9) and unmet spiritual needs (SDAT) are associated with a lower quality of life. We do not see a significant relation for the social evaluation factors.

Table 2.

Analysis of associations with the WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire—version for older people (WHOQOL-OLD), both overall and for each underlying dimension

| Characteristics | WHOQOL-OLD total | Sensory abilities | Autonomy | Death and dying | Past, present and future activities | Social participation | Intimacy |

| Age (years) | −0.031 (0.705) (11) |

0.095(0.224) (1) |

−0.088 (0.262)1 (1) |

0.088 (0.265) (4) |

−0.020 (0.797) (0) | −0.084 (0.284) (2) |

0.007 (0.933) (3) |

| Women (%) | 0.004 (0.965) (11) |

0.039 (0.614) (1) |

−0.013 (0.873) (1) | −0.047 (0.550) (4) | −0.038 (0.628) (0) | 0.024 (0.758) (2) | 0.015 (0.847) (3) |

| FIM | 0.204 (0.011) (12) |

0.170 (0.029) (2) |

0.312 (0.000) (2) |

−0.127 (0.107) (5) | 0.177 (0.023) (1) |

0.210 (0.007) (3) |

0.061 (0.443) (4) |

| MMS | 0.175 (0.029) (11) |

0.038 (0.631) (1) | 0.212 (0.006) (1) |

−0.062 (0.429) (4) | 0.202 (0.009) (0) | 0.202 (0.035) (2) |

0.157 (0.045) (3) |

| CIRS | −0.226 (0.033) (77) |

0.005 (0.961) (72) | −0.231 (9.025)(73) | −0.087 (0.407) (74) | −0.230 (0.025) (72) | −0.337 (0.001) (72) |

0.083 (0.430) (74) |

| PHQ-9 | −0.379 (0.000) (15) |

−0.331 (0.000) (5) | −0.319 (0.000) (5) |

−0.265 (0.001) (8) | −0.156 (0.047) (4) | −0.317 (0.000) (6) |

−0.101 (0.202) (7) |

| Living alone (%) | −0.063 (0.434) (11) |

−0.089 (0.255) (1) | 0.080 (0.308) (1) |

−0.052 (0.510) (4) | −0.098 (0.209) (0) | −0.048 (0.540) (2) | −0.170 (0.030) (3) |

| Home care before hospitalisation (%) | −0.238 (0.003) (11) |

−0.106 (0.174) (1) | −0.245 (0.002) (1) |

−0.119 (0.132) (4) | −0.048 (0.056) (0) | −0.152 (0.051) (2) | −0.072 (0.358) (3) |

| SDAT | −0.211 (0.049) (79) |

−0.152 (0.137) (70) | −0.182 (0.073) (69) |

−0.052 (0.619) (73) | −0.173 (0.089) (69) | −0.248 (0.015) (71) | −0.218 (0.034) (72) |

| QPP-SF | 0.264 (0.003) (38) |

0.045 (0.604) (31) |

0.247 (0.004) (31) |

0.074 (0.392) (32) |

0.179 (0.037) (30) |

0.307 (0.000) (31) |

0.245 (0.004) (33) |

| QPP-SF: medical-technical competences | 0.207 (0.011) (16) |

0.055 (0.488) (7) |

0.179 (0.024) (7) |

0.076 (0.345) (9) |

0.206 (0.009) (6) |

0.272 (0.001) (8) |

0.218 (0.006) (9) |

| QPP-SF: physical-technical conditions | 0.252 (0.002) (16) |

0.085 (0.286) (7) |

0.201 (0.011) (7) |

0.130 (0.104) (9) |

0.114 (0.150) (6) |

0.251 (0.001) (8) |

0.311 (0.000) (9) |

| QPP-SF: identity-oriented approach | 0.231 (0.006) (26) |

0.025 (0.758) (17) |

0.251 (0.002) (17) |

0.006 (0.947) (19) |

0.199 (0.014) (16) |

0.265 (0.001) (18) | 0.257 (0.002) (19) |

| QPP-SF: sociocultural atmosphere | 0.242 (0.004) (24) |

0.027 (0.739) (16) |

0.213 (0.009) (16) |

0.052 (0.529) (18) |

0.208 (0.010) (15) |

0.247 (0.002) (16) |

0.325 (0.000) (18) |

Spearman’s rank correlation, rs(p value). The no of missing values is indicated in parentheses.

CIRS, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; FIM, functional independence measure; MMS, mini-mental state; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (0–27); QPP-SF, quality from the patient’s perspective short form; SDAT, spiritual distress assessment tool.

Table 2 also describes the association between each of the dimensions of WHOQOL-OLD and the biopsychosocial and spiritual dimensions. Associations remain similar to those in the overall score except for ‘sensory abilities’ and ‘death and dying’, which are only connected with a limited number of markers.

Linear multivariate analysis of factors associated with quality of life

In multivariate analysis, mood (PHQ-9; β=−0.961, p<0.001) has a significant association with quality of life (table 3). Satisfaction with the care received is at the limit of having a significant relationship (QPP-SF; β=0.237, p=0.054) with quality of life. The variation explained by all the variables was 26.7% (F=4.170, p<0.001). No multicollinearity was identified between the explanatory variables, the maximal variance inflation factor was 1.58.

Table 3.

Multivariate linear analysis with multiple imputation to predict the total WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire—version for older people (WHOQOL-OLD) score

| Predictive factor | Total WHOQOL-OLD (11 missing values) | No of missing values | |

| β (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Age (years) | −0.025 (−0.301 to 0.251) | 0.861 | 0 |

| Women | 0.255 (−3.940 to 4.450) | 0.904 | 0 |

| FIM | 0.109 (−0.039 to 0.256) | 0.147 | 1 |

| MMS | 0.055 (−0.653 to 0.763) | 0.878 | 0 |

| CIRS | −0.007 (−0.617 to 0.603) | 0.983 | 72 |

| PHQ-9 | −0.961 (−1.449 to −0.472) | <0.001 | 4 |

| Living alone | −1.504 (−5.920 to 2.913) | 0.502 | 0 |

| Home care before hospitalisation | −2.302 (−6.898 to 2.294) | 0.321 | 0 |

| SDAT | −0.006 (−0.995 to 0.983) | 0.990 | 69 |

| QPP-SF | 0.237 (−0.004 to 0.479) | 0.054 | 30 |

β, regression coefficient.

CIRS, cumulative illness rating scale; FIM, functional independence measure; MMS, mini-mental state; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire-9; QPP-SF, quality from the patient’s perspective short form; SDAT, spiritual distress assessment tool.

Discussion

Elderly patients undergoing rehabilitation after acute care perceived a relatively high level of quality of life. For example, we found higher WHOQOL-OLD scores than those reported by Fang et al using data of a developmental study of the WHOQOL-OLD, which included 5566 respondents from 20 international centres (opportunistic sample of ill and well patients).32 To our knowledge, these are new data for this specific setting. This is not surprising, given this environment aims to offer stimulating conditions to promote and regain a good quality of life. In this study, quality of life had a significant relationship with mood (both in univariate and multivariate analysis) and functional status (only in univariate analysis). This link corresponds with research results found in other settings, such as those found in Conrad et al.33 Although only a limited number of patients performed the spiritual needs evaluation, the data show that patients with unmet spiritual needs experienced a poorer quality of life.

Patients had a high degree of satisfaction with the care they received. This result is consistent with previous studies with standard adult patients, showing that level of satisfaction is higher in rehabilitation setting.34 Satisfaction with care received is associated with quality of life. Such results are consistent with the literature in other settings, especially with those reported by Hartgering et al, which reported satisfaction with care received positively related to older patients’ quality of life in an acute care setting with global and integrated care.16 Further research is needed to better understand their inter-relationships.35

In addition to confirming the importance of the psychological dimension, the multivariate model does not allow us to draw conclusions about biopsychosocial factors related to quality of life. Functional status and cognitive status were not statistically significant in this multivariable linear regression, suggesting that, at least in this setting, they were not the most important drivers of perceived quality of life. This reflects that quality of life is complex and this study could only partially approach this complexity. Measuring quality of life, not fully explained from pooling descriptors of usual clinical practice, may surpass these traditional descriptors.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study was undertaken in a ‘real world’ clinical practice. The scales are employed in usual clinical practice and shared regularly in interdisciplinary meetings. The use of these tools, widely employed and validated in different clinical contexts, is likely to result in good ecological validity.

This study has certain limitations. First, the results apply only to a sample of elderly hospitalised patients without severe cognitive disorders, and thus cannot be generalised to patients with cognitive disorders. Furthermore, the rate of patients who did not participate might create a risk of selection-based bias, though slight, as the characteristics of the patients who participated and those who did not show no significant differences. In addition, all evaluations were not made at the same time (first and second week of hospitalisation), and we cannot exclude the possibility that symptomatic change may have occurred in some patients. In the context of data drawn from usual clinical practice, the social dimension can be misjudged and fail to demonstrate any link to quality of life; to avoid this result, a purpose-designed tool such as a scale of social support might be required.36 Such a scale would certainly show the importance of social support to quality of life.37 38 Similarly, some evaluations were not always undertaken: the chaplain worked part-time and was not able to conduct all the SDAT, despite excellent patient acceptance. The CIRS assessments were not systematically completed by the physicians. Conversely, missing data for the WHOQOL-OLD or the QPP-SF are from patients who did not respond to at least one of the questions asked, preventing calculation of the total score. Nevertheless, multiple imputation allowed us to limit the non-response bias in the multivariate analysis.

Implications for clinical practice

Evaluating quality of life is relevant in geriatric rehabilitation because we observe that variables traditionally used in clinical practice may not be sufficient to explain the quality of life and therefore insufficient to achieve that goal. Knowing the necessary elements for a good quality of life for each patient is fundamental to better understanding him/her and might improve guidance in setting goals of care. This information could contribute to offer truly patient-centred care in hospital environments and is therefore useful to the different professionals in charge of these patients.

However, further development of a biopsychosocial and spiritual model can only be encouraged. Similarly, this work suggests the importance of integrating an evaluation of the satisfaction with care received because it is also associated with quality of life.

Considering the following quotation: ‘Therapeutic success depends in part on the therapist’s ability to set a story in motion which is meaningful to the patient as well as to herself’,39 this work, which accounts for a patient’s quality of life, also has an ethical impact. In fact, this measure might help balance aspects of beneficence and respect for autonomy in a system that should not be paternalistic, but that also cannot meet all of a patient’s expectations.

Conclusion

Patients undergoing postacute geriatric rehabilitation perceive a good quality of life. Depressive symptoms were significantly associated with quality of life. In this setting, biopsychosocial and spiritual descriptors used in clinical practice are only moderately associated with quality of life. A follow-up to this study might evaluate how to better integrate quality of life in the construction of the care project, in addition to the usual descriptors of the clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: M-AB, ERT, ER and SM designed the research. M-AB and JP conducted statistical analysis. All authors interpreted the data. M-AB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in the writing of subsequent versions and approved the final article.

Funding: This work was supported by the Leenaards Foundation in the framework of the call for projects related to the “Quality of Life of Elderly Persons”.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Cantonal Committee of Vaud on the Ethics of Research on Human Subjects, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The full anonymised dataset can be provided on request.

References

- 1. Olsson IN, Runnamo R, Engfeldt P. Medication quality and quality of life in the elderly, a cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:95 10.1186/1477-7525-9-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bowling A, Seetai S, Morris R, et al. . Quality of life among older people with poor functioning. The influence of perceived control over life. Age Ageing 2007;36:310–5. 10.1093/ageing/afm023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Netuveli G, Blane D. Quality of life in older ages. Br Med Bull 2008;85:113–26. 10.1093/bmb/ldn003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Papadopoulos C, Jagsch R, Griesser B, et al. . Health-related quality of life of patients with hip fracture before and after rehabilitation therapy: discrepancies between physicians' findings and patients' ratings. Aging Clin Exp Res 2007;19:125–31. 10.1007/BF03324678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:977–88. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00411-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Solomon R, Kirwin P, Van Ness PH, et al. . Trajectories of quality of life in older persons with advanced illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:837–43. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02817.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. González-Salvador T, Lyketsos CG, Baker A, et al. . Quality of life in dementia patients in long-term care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15:181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Montuclard L, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF, et al. . Outcome, functional autonomy, and quality of life of elderly patients with a long-term intensive care unit stay. Crit Care Med 2000;28:3389–95. 10.1097/00003246-200010000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jahelka B, Dorner T, Terkula R, et al. . Health-related quality of life in patients with osteopenia or osteoporosis with and without fractures in a geriatric rehabilitation department. Wien Med Wochenschr 2009;159:235–40. 10.1007/s10354-009-0655-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weber DC, Fleming KC, Evans JM. Rehabilitation of geriatric patients. Mayo Clin Proc 1995;70:1198–204. 10.4065/70.12.1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pain K, Dunn M, Anderson G, et al. . Quality of life: What does it mean in rehabilitation. J Rehabil Assist Technol Eng 1998;64:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Psychodyn Psychiatry 2012;40:377–96. 10.1521/pdps.2012.40.3.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wells JL, Seabrook JA, Stolee P, et al. . State of the art in geriatric rehabilitation. Part I: review of frailty and comprehensive geriatric assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:890–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sulmasy DP. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist 2002;3:24–33. 42 Spec 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chally PS, Spirituality CJM. rehabilitation, and aging: a literature review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:60–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hartgerink JM, Cramm JM, Bakker TJ, et al. . The importance of older patients' experiences with care delivery for their quality of life after hospitalization. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:311 10.1186/s12913-015-0982-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tierney RM, Horton SM, Hannan TJ, et al. . Relationships between symptom relief, quality of life, and satisfaction with hospice care. Palliat Med 1998;12:333–44. 10.1191/026921698670933919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, et al. . Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist 1970;10:20–30. 10.1093/geront/10.1_Part_1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179–86. 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Keith RA, et al. . Advances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitation. Top Geriatr Rehabil 1986;1:59–74. 10.1097/00013614-198604000-00007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, et al. . Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: application of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. Psychiatry Res 1992;41:237–48. 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carballeira Y, Dumont P, Borgacci S, et al. . Criterion validity of the french version of Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) in a hospital department of internal medicine. Psychol Psychother 2007;80:69–77. 10.1348/147608306X103641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leplège A, Perret-Guillaume C, Ecosse E, et al. . [A new instrument to measure quality of life in older people: The French version of the WHOQOL-OLD]. Rev Med Interne 2013;34:78–84. 10.1016/j.revmed.2012.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Power M, Quinn K, Schmidt S, et al. . Development of the WHOQOL-old module. Qual Life Res 2005;14:2197–214. 10.1007/s11136-005-7380-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Larsson G, Larsson BW, Munck IM. Refinement of the questionnaire ’quality of care from the patient’s perspective' using structural equation modelling. Scand J Caring Sci 1998;12:111–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wilde Larsson B, Larsson G. Development of a short form of the Quality from the Patient’s Perspective (QPP) questionnaire. J Clin Nurs 2002;11:681–7. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00640.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monod S, Martin E, Spencer B, et al. . Validation of the Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool in older hospitalized patients. BMC Geriatr 2012;12:13 10.1186/1471-2318-12-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Monod SM, Rochat E, Büla CJ, et al. . The spiritual distress assessment tool: an instrument to assess spiritual distress in hospitalised elderly persons. BMC Geriatr 2010;10:88 10.1186/1471-2318-10-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice : Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fang J, Power M, Lin Y, et al. . Development of short versions for the WHOQOL-OLD module. Gerontologist 2012;52:66–78. 10.1093/geront/gnr085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Conrad I, Matschinger H, Riedel-Heller S, et al. . The psychometric properties of the German version of the WHOQOL-OLD in the German population aged 60 and older. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014;12:105 10.1186/s12955-014-0105-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Keith RA. Patient satisfaction and rehabilitation services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:1122–8. 10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90182-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Asadi-Lari M, Tamburini M, Gray D. Patients' needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: towards a comprehensive model. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:32 10.1186/1477-7525-2-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lubben JE. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam Community Health 1988;11:42–52. 10.1097/00003727-198811000-00008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Helgeson VS. Social support and quality of life. Qual Life Res 2003;12:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Newsom JT, Schulz R. Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychol Aging 1996;11:34–44. 10.1037/0882-7974.11.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mattingly C. The concept of therapeutic ’emplotment'. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:811–22. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90153-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.