Abstract

Objective

The aim of this paper was to identify the key factors of case management (CM) interventions among frequent users of healthcare services found in empirical studies of effectiveness.

Design

Thematic analysis review of CM studies.

Methods

We built on a previously published review that aimed to report the effectiveness of CM interventions for frequent users of healthcare services, using the Medline, Scopus and CINAHL databases covering the January 2004–December 2015 period, then updated to July 2017, with the keywords ‘CM’ and ‘frequent use’. We extracted factors of successful (n=7) and unsuccessful (n=6) CM interventions and conducted a mixed thematic analysis to synthesise findings. Chaudoir’s implementation of health innovations framework was used to organise results into four broad levels of factors: (1) environmental/organisational level, (2) practitioner level, (3) patient level and (4) programme level.

Results

Access to, and close partnerships with, healthcare providers and community services resources were key factors of successful CM interventions that should target patients with the greatest needs and promote frequent contacts with the healthcare team. The selection and training of the case manager was also an important factor to foster patient engagement in CM. Coordination of care, self-management support and assistance with care navigation were key CM activities. The main issues reported by unsuccessful CM interventions were problems with case finding or lack of care integration.

Conclusions

CM interventions for frequent users of healthcare services should ensure adequate case finding processes, rigorous selection and training of the case manager, sufficient intensity of the intervention, as well as good care integration among all partners. Other studies could further evaluate the influence of contextual factors on intervention impacts.

Keywords: case management, frequent users, implementation, outcomes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The 13 studies included in this paper were identified by a rigorous search strategy used in a previous review of case management (CM) interventions for frequent users of healthcare services.

Material from qualitative studies was not included in the analysis.

Little description of CM interventions was provided in the included studies.

Introduction

Frequent users of healthcare services are a small group of patients accounting for a high number of healthcare visits, often emergency department (ED), and important costs.1–3 They use healthcare services for complex health needs,4–6 combining multiple chronic conditions with psychosocial or mental health comorbidities.5 7 8 Frequent use of services is often considered inappropriate7 9 and may be a symptom of gaps in accessibility and coordination of care.10 11 These patients are more at risk for incapacity, poorer quality of life and mortality.12–15 Regardless of healthcare setting, case management (CM) is the most frequently implemented intervention to improve care for frequent users of healthcare services and to reduce healthcare usage and cost.16 17

CM is a ‘collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality cost-effective outcomes’.18 Reviews reported positive outcomes associated with CM interventions among frequent users of healthcare services such as decreases in ED use and cost.16 17 19–21 They also concluded that CM interventions resulted in a better use of appropriate existing resources22 and a reduction in social problems such as homelessness and drug and alcohol abuse.22–24

A small number of systematic reviews briefly addressed enabling factors of successful CM interventions in the discussion section of their paper. In a review on the effectiveness of CM among frequent ED users, Kumar and Klein19 noted that frequency of follow-up, availability of psychosocial services, assistance with financial issues and active engagement of the case manager and the patient were important characteristics of CM interventions. Oeseburg et al25 evaluated the effects of CM for frail older people (not necessarily frequent users) and highlighted that well-trained case managers with competent skills in designing care plans and coordinating services, effective communication and collaboration between the members of the healthcare team, as well as the acceptance of the case manager as the coordinator for care delivery, were key factors of CM. However, the identification of key factors of CM interventions was not a primary objective of these reviews, although this information would be useful to inform researchers and decision makers on the implementation of CM.

The aim of this paper was to identify the key factors of CM interventions among frequent users of healthcare services found in empirical studies of effectiveness.

Methods

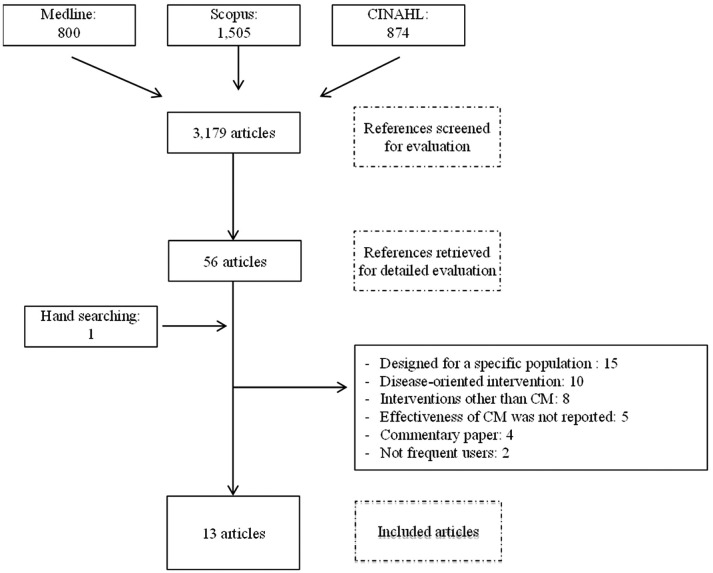

We first conducted a scoping review that aimed to report the effectiveness of CM for frequent users of healthcare services, using the Medline, Scopus and CINAHL databases covering the January 2004–December 2015 period, with the keywords ‘CM’ and ‘frequent use’.20 To be included in the review, studies had to report on the effects of a CM intervention on healthcare usage and/or cost. We excluded studies limited to a specific group of patients and interventions targeting a single disease. The review included 11 articles and concluded that CM could reduce healthcare use and cost. A detailed description of the articles included and the CM interventions is provided in the published review.20 For the purpose of this paper, the search strategy was updated to July 2017, therefore, two additional articles were added (figure 1), for a total of 13 studies.

Figure 1.

Scoping review flow chart of search results (2004–July 2017). CM, case management.

We then extracted factors of successful (n=7) and unsuccessful (n=6) CM interventions to conduct a mixed thematic analysis to synthesise findings across the studies26–28 using a framework proposed by Chaudoir et al.29 This framework was developed to reflect factors hypothesised to impact outcomes and was used to capture the characteristics of CM interventions, while allowing comparisons among the studies included. According to this framework, the relevant factors were organised into four broad levels to address in the implementation of a health innovation: (1) environmental/organisational level: setting and structure in which CM is being implemented, including physical environmental, public policies, infrastructures, economical, political and social contexts and different features of the organisation (eg, leadership effectiveness, organisational culture and staff satisfaction towards the organisation); (2) practitioner level: characteristics and experience of the provider who is in contact with patients for the purpose of CM, including attitudes and beliefs towards CM, professional role and capacities; (3) patient level: characteristics and experience of the patient, including motivation, perception, personality traits, risk factors, skills and abilities and (4) programme level: aspects of CM, including characteristics and activities (evaluation, patient education, self-management support, referrals, transition, etc) as well as compatibility of the intervention with the organisation and adaptability.29–31

Results

Description of the studies

The 13 studies are described in table 1. Seven studies (two non-randomised controlled studies32 33 and five before–after studies34–38) reported positives outcomes on healthcare usage or cost. Wetta-Hall37 evaluated a multidisciplinary CM intervention among frequent ED users and demonstrated a decrease in ED use as well as an improvement in physical quality of life. Crane et al32 assessed a multidisciplinary CM intervention including a care plan among frequent ED users and observed a decrease in ED use and healthcare cost. Shah et al33 conducted a study with low-income, uninsured patients on the implementation of a care plan by a case manager and demonstrated that ED use, as well as cost, had significantly decreased. Pillow et al34 conducted a before–after study with the top ED frequent users to measure the impact of a multidisciplinary CM intervention including a care plan and reported a trend towards a decrease in ED use. Rinke et al35 in a study evaluating the impact of the implementation of a care plan by a case manager for the most frequent emergency medical services (EMS) users, as well as Tadros et al,36 in a study evaluating a CM intervention conducted by a case manager among frequent EMS users, observed a decrease in EMS cost and use. Finally, Grover et al38 evaluated the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary CM intervention including a care plan among frequent ED users and reported a reduction in ED use and radiation exposure, improved efficacy of referral, but no change in number of admissions.

Table 1.

Description of the studies evaluating CM interventions among frequent users of healthcare services

| Source (location) | Design | Definition of frequent users | n | Intervention | Outcomes |

| Bodenmann et al39 (Switzerland) | Randomised controlled trial | 5 ED visits and more in a year | I=125 C=125 |

A care plan was developed by a multidisciplinary team and offered counselling on substance abuse, patient navigation, referral to social, mental and health services and assistance in resolving income, housing, health insurance, education and domestic violence issues. | No change on ED use |

| Crane et al32

(USA) |

Non-randomised controlled study | 6 ED visits and more in 1 year | I=36 C=36 |

A care plan was developed by a multidisciplinary team and offered individual and group medical meetings, counselling group sessions and telephone access to a case manager. | Reduction in ED use and in total healthcare cost |

| Grover et al38

(USA) |

Before–after study | 5 ED visits and more in 1 month. | 199 | A care plan was developed by a multidisciplinary team and was entered into the ED electronic system. They offered referrals to healthcare and social services and limitation of narcotic prescriptions (if needed). A review of the care plan was done if changes occurred in a patient’s condition or use of ED services. | Reduction in ED use |

| Lee and Davenport 8

(USA) |

Before–after study | 3 ED visits and more in 1 month associated with symptoms of unresolved pain, drug seeking or lack of primary care physician | 50 | With the collaboration of primary care providers, a nurse case manager offered referrals to healthcare and social services, assistance with insurance issues and limited narcotic prescriptions. | No change on ED use |

| Peddie et al42

(New Zealand) |

Non-randomised controlled trial | 10 ED visits and more in 1 year | I=87 C=77 |

A care plan was developed by a multidisciplinary team (including the patient) and was entered into the ED electronic system. The CM intervention also offered free visits with a general practitioner and CM meetings with a multidisciplinary team for the patients with the most complex needs. | No change on ED use |

| Phillips et al22

(Australia) |

Before–after study | 6 ED visits and more in 1 year | 60 | A multidisciplinary team offered hospital-based care, community healthcare, primary healthcare and short-term and long-term CM. | Increased ED use, improved primary and community care engagement, improved housing stability, no change on number of admissions, ED disposition, ED length of stay, ED triage category, drug and alcohol use and EMS use |

| Pillow et al34

(USA) |

Before–after study | Top 50 chronic ED frequent users | 50 | A care plan was developed by a multidisciplinary team and offered psychosocial and psychiatric assessments, pain contract, radiology and urinary toxicology studies, outpatient and managed care referrals. An ED tracking system was implemented to identify frequent users while facilitating access to the care plan. | Reduction in ED use, but no change in number of admissions. |

| Rinke et al35

(USA) |

Before–after study | Top 25 frequent EMS users | 10 | A care plan was developed by a case manager and offered coordinated care referrals to psychosocial services, patient education and telephone access to healthcare support. | Reduction in EMS use and cost* |

| Segal et al40 (Australia) | Randomised controlled trial | More than US$4000 of healthcare costs over a 2-year period | I=2074 C=668 |

A care plan was developed by the care coordinator and the patient. CM intensity was determined by patients’ likely future risk of hospital admission: Low risk: care plan reviewed every 12 months; Medium- risk: care plan reviewed every 6 months and telephone contact to monitor implementation of the care plan and address emergent problems; High risk: care plan reviewed every 3 months and traditional intensive CM services including an advocacy role. | Increase in total healthcare costs and hospital-based outpatient costs. No change on admission costs, medication costs, quality of life and mortality |

| Shah et al33

(USA) |

Non-randomised controlled study | 4 ED visits or admissions and more, or three admissions and more, or two admissions and more as well as 1 ED visit and more in 1 year | I=98 C=160 |

A care manager helped patients access and coordinate services needed. He offered goal setting and assistance, health navigation; access to support services, care transitions and communication with providers. | Reduction in ED use and cost as well as admission cost, but no change on no of admissions. |

| Sledge et al41

(USA) |

Randomised controlled trial | 2 admissions and more in 1 year | I=47 C=49 |

A care plan was developed by a multidisciplinary team and offered follow-up to the patient in primary care by promoting coordination of care, self-care patterns, coping skills, and providing assistance with referrals and appointments. | No change on no of admissions, ED use, total healthcare costs, quality of life and patient satisfaction |

| Tadros et al36

(USA) |

Before–after study | 10 EMS transports and more in a 1 year, or referred by fire and EMS personnel | 51 | A coordinator helped patients with access and coordination of needs. He offered investigation for factors underlying the excessive use of healthcare services, coordination of care with other health and social services and patient education. | Reduction in EMS use and cost* as well as total healthcare cost*, but no change in no of admissions and cost, ED use and cost. |

| Wetta-Hall37

(USA) |

Before–after study | 3 ED visits and more in 6 months | 492 | A multidisciplinary team helped patient’s access to community resources, navigate the healthcare system, and find primary care resources. They offered goal setting, coordination of care, referrals for healthcare needs, patient education and supporting patient connections with informal support networks. | Reduction in ED use and improved quality of life, but no change in health locus of control. |

C, Control group; CM, case management; ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical services; I, Intervention group.

* Not stated if the outcome was significant or not.

Six studies reported no benefit on healthcare usage or cost, including three randomised controlled trials,39–41 two before–after studies8 22 and one non-randomised controlled study.42 The study by Bodenmann et al39 on the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary CM intervention including a care plan and the pilot study by Lee and Davenport8 on a nurse CM intervention reported no change on ED use. Peddie et al42 came to the same conclusion in a study evaluating the impact of a management plan on the frequency of ED visits. Sledge et al41 conducted a study to evaluate a clinic-based ambulatory CM intervention and reported no significant change on number of admissions, ED use, total healthcare cost, quality of life and patient satisfaction. In a study evaluating the effectiveness of multidisciplinary CM, Phillips et al22 observed an increase in ED use and no change on admissions. Similarly, in a study on a care coordination programme including care planning by a general practitioner and CM intervention, Segal et al40 reported an increase in total healthcare and outpatient costs and no change on admissions and medication costs, as well as quality of life.

Key factors of CM intervention

Successful and unsuccessful factors of CM interventions are shown in tables 2 and 3, classified according to Chaudoir et al’s29 framework.

Table 2.

Characteristics of case management studies reporting positive findings, presented according to Chaudoir’s framework

| Environment/organisation | Practitioner | Patient | Programme | |

| Crane et al32 |

|

|

|

|

| Grover et al38 |

|

|

||

| Shah et al33 |

|

|

||

| Pillow et al34 |

|

|

|

|

| Rinke et al35 |

|

|

||

| Tadros et al36 |

|

|

||

| Wetta-Hall37 |

|

|

ED, emergency department.

Table 3.

Characteristics of CM studies reporting no benefit, presented according to Chaudoir’s framework

| Environment/organisation | Practitioner | Patient | Programme | |

| Bodenmann et al39 |

|

|

||

| Lee and Davenport 8 |

|

|

||

| Peddie et al42 |

|

|||

| Phillips et al22 |

|

|

|

|

| Segal et al40 |

|

|

||

| Sledge et al41 |

|

|

|

CM, case management; ED, emergency department; PCP, primary care provider.

Most authors reported that access to, and close relationships between, case managers and their partners (healthcare providers at the hospital and clinics, staff from community organisations, etc) were key factors of CM interventions as well as engagement and involvement of healthcare and community partners.8 33 34 38 Two studies reported lack of collaboration between the case manager and primary care providers and lack of integration into a systemic approach to care as major flaws.8 41

The selection and training of the case manager was also mentioned as a key factor. A dedicated, trusting and experienced case manager could improve patient engagement in CM and foster better patient involvement in self-management.32 34 35 Conversely, authors of two studies highlighted the difficulty of finding a well-trained case manager as a main limitation of their study.22 41 Engagement of the case manager, as well as all the healthcare providers involved in the intervention, and their capacity to motivate the patient were also important, highlighting the need of having practitioners who feel buy-in in regard to the intervention.34

Pillow et al34emphasised the importance of recruiting patients with greatest needs, namely very high ED users with complex healthcare needs. In three studies that did not demonstrate benefit, many patients did not have complex needs and/or were not the highest users of healthcare services,39 40 or had substance abuse or psychosocial issues without a chronic condition.22

Coordination of care,35 36 patient education and self-management support,8 32–34 and assistance to navigate in the healthcare system33 35 37 were key activities of successful CM interventions. Most of the studies included a care plan based on an evaluation of patient needs; five observed a reduction in healthcare use,32–35 38 whereas four reported no benefit.39–42 Revision of the care plan by a multidisciplinary team during the CM intervention, in response to a better understanding of patient needs or to a change in patient health condition seemed an important factor.34 35 38 Frequent contacts with the patient, either by telephone or in person, were also useful.32 33 35

Discussion

This paper is the first thematic analysis review synthesising key factors of CM interventions among frequent users of healthcare services. Access to, and close partnerships with, healthcare providers and community services resources were key factors of CM interventions that should target patients with the greatest needs and promote frequent contacts with the healthcare team. The selection and training of the case manager was also an important factor to consider in order to foster patient engagement in CM. Coordination of care, self-management support and assistance with care navigation were key CM activities. The main issues with unsuccessful CM interventions were problems in case finding or lack of care integration.

In a series of reports from The King’s Fund about the implementation of CM for people with long-term conditions, Ross et al43 stressed the role and skills of the case manager, appropriate case finding and caseload, single point of access for patients, continuity of care, self-management support, interprofessional collaboration and development of information systems for the effective use of data and communication processes. Convergent findings were reported in a synthesis by Berry-Millett and Bodenheimer44 that aimed to examine the impact of CM to improve care and reduce healthcare costs for frequent users with complex needs. They identified six factors of successful CM, namely selecting high-risk patients, promoting face-to-face meetings, training case managers with low caseloads, creating multidisciplinary teams where physicians and case managers work in the same location, involving peers and promoting self-management skills. Our review, which aimed to identify key factors of CM as a primary objective, corroborates and completes these results, by a rigorous thematic analysis of 13 empirical studies on the topic.

As already noted by other authors,45 context description was lacking in most studies. As a complex intervention, CM includes various components interacting in a nonlinear way to produce outcomes that are highly dependent on context and variables across settings.46 47 Special attention should be paid to contextual factors of CM. Indeed, further studies could analyse not only if and how CM works for frequent users of healthcare services but also in what contexts.

Limitations

Description of CM interventions was a limit of many studies included. According to the International Classification of Health Interventions,48 the coordination target for what was done was different in the studies. Including material from qualitative studies could enrich results in further steps.

Conclusions

CM interventions for frequent users of healthcare services should ensure adequate case-finding processes, rigorous selection and training of the case manager, sufficient intensity of the intervention and good care integration among all partners. Other studies could further evaluate the influence of contextual factors on intervention impacts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Susie Bernier for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: CH and M-CC developed the study and participated in its design and coordination. ML conducted the data collection and drafted the manuscript under the supervision of CH and M-CC. All authors were involved in drafting and editing the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Patient consent: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Follow the money--controlling expenditures by improving care for patients needing costly services. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1521–3. 10.1056/NEJMp0907185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Commission on the Reform of Ontario’s Public Services. Public services for Ontarians: a path to sustainability and excellence. Ottawa: Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. LaCalle E, Rabin E. Frequent users of emergency departments: the myths, the data, and the policy implications. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:42–8. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hansagi H, Olsson M, Sjöberg S, et al. Frequent use of the hospital emergency department is indicative of high use of other health care services. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:561–7. 10.1067/mem.2001.111762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan BT, Ovens HJ. Frequent users of emergency departments. Do they also use family physicians' services? Can. Fam. Physician 2002;48:1654–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Byrne M, Murphy AW, Plunkett PK, et al. Frequent attenders to an emergency department: a study of primary health care use, medical profile, and psychosocial characteristics. Ann Emerg Med 2003;41:309–18. 10.1067/mem.2003.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruger JP, Richter CJ, Spitznagel EL, et al. Analysis of costs, length of stay, and utilization of emergency department services by frequent users: implications for health policy. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:1311–7. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb01919.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee KH, Davenport L. Can case management interventions reduce the number of emergency department visits by frequent users? Health Care Manag 2006;25:155–9. 10.1097/00126450-200604000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murphy AW, Leonard C, Plunkett PK, et al. Characteristics of attenders and their attendances at an urban accident and emergency department over a one year period. J Accid Emerg Med 1999;16:425–7. 10.1136/emj.16.6.425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lowe RA, Localio AR, Schwarz DF, et al. Association between primary care practice characteristics and emergency department use in a medicaid managed care organization. Med Care 2005;43:792–800. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000170413.60054.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haggerty JL, Roberge D, Pineault R, et al. Features of primary healthcare clinics associated with patients' utilization of emergency rooms: urban-rural differences. Healthc Policy 2007;3:72–85. 10.12927/hcpol.2007.19394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fuda KK, Immekus R. Frequent users of Massachusetts emergency departments: a statewide analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:16.e1–16.e8. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Browne GB, Humphrey B, Pallister R, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of frequent attenders in a prepaid Canadian family practice. J Fam Pract 1982;14:63–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hansagi H, Allebeck P, Edhag O, et al. Frequency of emergency department attendances as a predictor of mortality: nine-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. J Public Health Med 1990;12:39–44. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kersnik J, Svab I, Vegnuti M. Frequent attenders in general practice: quality of life, patient satisfaction, use of medical services and GP characteristics. Scand J Prim Health Care 2001;19:174–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Althaus F, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58:41–52. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soril LJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: a systematic review of interventions. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123660 10.1371/journal.pone.0123660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Case Management Society of America. What is a case manager? http://www.cmsa.org/Home/CMSA/WhatisaCaseManager/tabid/224/Default.aspx

- 19. Kumar GS, Klein R. Effectiveness of case management strategies in reducing emergency department visits in frequent user patient populations: a systematic review. J Emerg Med 2013;44:717–29. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Lambert M, et al. Effectiveness of case management interventions for frequent users of healthcare services: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012353 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stokes J, Panagioti M, Alam R, et al. Effectiveness of case management for ’At Risk' patients in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132340 10.1371/journal.pone.0132340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Phillips GA, Brophy DS, Weiland TJ, et al. The effect of multidisciplinary case management on selected outcomes for frequent attenders at an emergency department. Med J Aust 2006;184:602–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, et al. The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:603–8. 10.1053/ajem.2000.9292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shumway M, Boccellari A, O’Brien K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of clinical case management for ED frequent users: results of a randomized trial. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:155–64. 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oeseburg B, Wynia K, Middel B, et al. Effects of case management for frail older people or those with chronic illness: a systematic review. Nurs Res 2009;58:201–10. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181a30941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:6–20. 10.1258/1355819054308576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kastner M, Tricco AC, Soobiah C, et al. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:114 10.1186/1471-2288-12-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A methods sourcebook. 3rd ed London: Sage Publications Inc, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci 2013;8:22 10.1186/1748-5908-8-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41:327–50. 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crane S, Collins L, Hall J, et al. Reducing utilization by uninsured frequent users of the emergency department: combining case management and drop-in group medical appointments. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:184–91. 10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shah R, Chen C, O’Rourke S, et al. Evaluation of care management for the uninsured. Med Care 2011;49:166–71. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182028e81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pillow MT, Doctor S, Brown S, et al. An Emergency Department-initiated, web-based, multidisciplinary approach to decreasing emergency department visits by the top frequent visitors using patient care plans. J Emerg Med 2013;44:853–60. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rinke ML, Dietrich E, Kodeck T, et al. Operation care: a pilot case management intervention for frequent emergency medical system users. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:352–7. 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tadros AS, Castillo EM, Chan TC, et al. Effects of an emergency medical services-based resource access program on frequent users of health services. Prehosp Emerg Care 2012;16:541–7. 10.3109/10903127.2012.689927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wetta-Hall R. Impact of a collaborative community case management program on a low-income uninsured population in Sedgwick County, KS. Appl Nurs Res 2007;20:188–94. 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grover CA, Crawford E, Close RJ. The efficacy of case management on emergency department frequent users: An Eight-Year Observational Study. J Emerg Med 2016;51:595–604. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bodenmann P, Velonaki VS, Griffin JL, et al. Case management may reduce emergency department frequent use in a universal health coverage system: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:508–15. 10.1007/s11606-016-3789-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Segal L, Dunt D, Day SE, et al. Introducing co-ordinated care (1): a randomised trial assessing client and cost outcomes. Health Policy 2004;69:201–13. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sledge WH, Brown KE, Levine JM, et al. A randomized trial of primary intensive care to reduce hospital admissions in patients with high utilization of inpatient services. Dis Manag 2006;9:328–38. 10.1089/dis.2006.9.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Peddie S, Richardson S, Salt L, et al. Frequent attenders at emergency departments: research regarding the utility of management plans fails to take into account the natural attrition of attendance. N Z Med J 2011;124:61–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ross S, Curry N, Goodwin N. Case Management: What it is and how it can best be implemented. London, UK: The King’s Funds, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Berry-Millett R, Bodenheimer TS. Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Synth Proj Res Synth Rep 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Petticrew M, Rehfuess E, Noyes J, et al. Synthesizing evidence on complex interventions: how meta-analytical, qualitative, and mixed-method approaches can contribute. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:1230–43. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shepperd S, Lewin S, Straus S, et al. Can we systematically review studies that evaluate complex interventions? PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000086 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pawson R. Nothing as Practical as a Good Theory. Evaluation 2003;9:471–90. 10.1177/1356389003094007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. ICHI. ICHI Alpha 2016. https://mitel.dimi.uniud.it/ichi/#

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.