Abstract

Objectives

Obesity has been found to be associated with an elevated risk of thyroid nodule(s), mainly in adults; however, evidence for this association in children was limited. The objective of this study was to investigate the association of adiposity and thyroid nodule(s) in children living in iodine-sufficiency areas.

Setting and participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study of 1403 Chinese children living in the East Coast of China in 2014.

Outcome measures

Anthropometric measures including height, weight and waist and hip circumferences were taken, and body mass index (BMI), body surface area (BSA) and waist–hip ratio (WHR) were then calculated. Thyroid ultrasonography was performed to assess thyroid volume and nodules.

Results

Based on BMI, 255 (18.17%) children were overweight and 174 (12.40%) were obese. Thyroid nodule(s) was detected in 18.46% of all participants and showed little age and sex variations. As compared with normal-weight children, obese children experienced significantly higher risks for solitary (OR 2.07 (95% CI 1.16 to 3.71)) and multiple (OR 1.67 (95% CI 1.03 to 2.70)) thyroid nodules. Similar associations with thyroid nodule(s) were observed with adiposity measured by waist circumference and BSA, but not WHR. There were no notable differences in the associations between children consuming iodised and non-iodised salt.

Conclusions

These findings provide further evidence that childhood obesity is associated with the risk for thyroid nodule(s).

Keywords: adiposity, thyroid nodule(s), children, iodine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large sample size, directly measured thyroid ultrasonography and various anthropometric measurements following a standardised protocol.

Detailed information distinguishing solitary and multiple nodules and household iodised salt consumption status at the individual level.

Lack of information on thyroid function.

Introduction

Thyroid nodule (TN) is a common thyroid disorder globally, and the incidence has been increasing in recent decades.1 2 Thyroid ultrasound investigations have documented very high prevalences (approaching 50%) of TNs worldwide.3–5 Potential risk factors for TNs include age, sex, iodine intake,3 6–8 demographic parameters, clinical history and waist circumference (WC).2 9 Both mildly deficient iodine intake and excessive iodine intake are risk factors for TN(s) in normal subjects.10

Obesity is a known risk factor for a number of chronic conditions and may also increase the risk of thyroid cancer.11–15 The recent increase in TNs and thyroid cancer may partly be due to the epidemic of obesity.9 16 17 Elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and declined free thyroxin (FT4) levels have been observed in obese patients.16 However, previous studies of the associations between obesity and thyroid were mainly conducted in adults, and the results were not entirely consistent. Whether these observations from adults can be applied to children is not clear particularly because the incidence of TNs is lower but the risk for malignancy is greater in children as compared with adults.18

In the current study, we conducted a large-scale epidemiological study to determine the associations of a number of anthropometric measurements including body mass index (BMI), body surface area (BSA), WC and waist–hip ratio (WHR) with solitary or multiple TNs in school-age children.

Methods

Study population

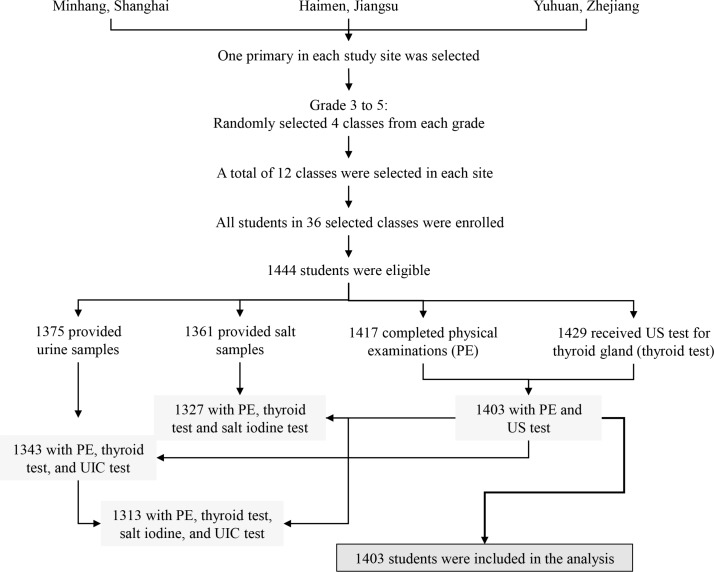

Randomised cluster sampling was used to selected subjects. Similar study methodologies have been reported in an earlier study.19 Briefly, three coastal cities in East China (Minhang District in Shanghai, Haimen City in Jiangsu Province and Taizhou City in Zhejiang Province) were selected by purposive sampling. Previous studies have revealed an iodine-sufficient status20–22 along with distinguished iodised salt consumption proportions among three sites. One primary school (students were mainly local residents) was selected from each city to ensure a good representativeness. Four classes in each grade from grade 3 to grade 5 in these schools were randomly selected in 2014 and all students in 12 selected classes in each school were enrolled into this study (figure 1). Among 1444 eligible children, an ultrasound test for thyroid gland volume was performed on 1429 students and 1403 of them completed routine physical examinations. A total of 1375 students provided first morning urine samples. Based on data from 1403 students who completed physical examinations and thyroid test, we determined the prevalence of TN(s) and the influences of overweight and obesity. Written consent from parents or guardians of all participants were received, and the study was approved by the ethical review board of the School of Public Health of Fudan University.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the study design. UIC, urinary iodine concentration; US, ultrasound.

Study variables

The outcome variables in this study were having TN(s) (no, yes) and number of TNs (no nodule, solitary nodule, multiple nodules). Adiposity measurements were explanatory variables, including BMI, BSA, WCs and WHR. Sex, age, urinary iodine concentrations (UICs) and iodised salt consumption status were covariates in the multivariate regression models.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements, including standing height (cm), weight (kg) and circumferences of the waist, hip and chest (cm) were taken by trained health professionals according to a standard protocol. The standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm without shoes. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital weight scale. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres, and all participants were categorised into three groups of under/normal weight, overweight and obesity status according to the BMI growth reference values for Chinese children.23 The cut-offs for overweight and obesity in boys were 17.8 and 20.1 for age 8, 18.5 and 21.1 for age 9, 19.5 and 22.2 for age 10 and 20.1 and 23.2 for age 11. The corresponding cut-offs for girls were 17.3 and 19.5, 17.9 and 20.4, 18.7 and 21.5, and 19.6 and 22.7, respectively. BSA was calculated by using the following formula: BSA=(Weight0.425)×(Height0.725)×0.007184.24 WHR was calculated as WC divided by hip circumference. BSA, WC and WHR were categorised into quintiles to assess their relations with TNs.

Thyroid ultrasonography

All participants received thyroid ultrasonography performed by experienced examiners at school using a real-time sector scanner with a 7.5 MHz/40 mm probe linear transducer. The ultrasonographic examination was carried out on the children lying on a desk with the neck extended. Standardised thyroid ultrasound technique was adopted according to the method described by Fuse et al.25 Discrete lesion(s) within the thyroid gland that was palpably and/or ultrasonographically distinct from the surrounding thyroid parenchyma was defined as TN(s).26 In case of abnormality in the sonographic examination of the thyroid, parents of the children would receive a written note describing the abnormal results of the examination and be advised to take their children to visit a physician. All participants were categorised as having no nodule or having nodule(s) (solitary nodule and multiple nodules) according to their TN detection status.

Urine and salt samples collection and iodine concentration analyses

First, morning urine sample was collected for each participant. Students were also asked to bring a salt sample of more than 20 g from home for iodine measurement.

UIC was determined following the method proposed by the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China (WS/T107.2006 and GB/T13025.7-1999).27 Salt iodine content was also measured using a national standard method with a proper quality control28 (GB/T13025.7-1999). Urine samples (10%) were assayed in duplicate, and no statistical differences were observed as compared with the primary results.

Iodine nutrition status was determined at a population level according to WHO/Unicef/International Council for Control of Iodinedeficiency Disorders (ICCIDD): insufficient (UIC <100 µg/L), sufficient (100–199 µg/L), more than adequate (200–299 µg/L) and excessive (≥300 µg/L). Iodised salt consumption status was grouped into two categories: non-iodised salt (<5 mg/kg) and iodised salt (≥5 mg/kg).29

Statistical analysis

χ2 test was used to examine TNs in relation to sex, age, BMI, iodised salt consumption status, urinary iodine level and study area. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to examine the associations of various anthropometric measurements with the frequency of TNs (no nodule, solitary nodule and multiple nodules). Due to a considerable day-to-day variation in iodine excretion, one-spot urinary iodine level was not a proper indicator of iodine status for individuals.30 31 Therefore, in current analysis, iodised salt consumption instead of iodine concentration in urine was included in the multivariate models. We also assessed the correlation between UIC and iodised salt consumption and observed a significantly higher level of UIC in children who consumed iodised salt at home, suggesting that iodised salt consumption status could be a good proxy for iodine nutrition at a population level. Multivariable logistic regression models were then used to adjust for age, sex and iodised salt consumption. Potential effect modifications by sex, age and iodised salt consumption on the associations of interest were also examined by including associated interaction terms into the multivariate analysis. We also reanalysed the data by using mixed effects with survey schools as random effect and observed no statistical significance of random effect in the generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) (p=0.320).

All analyses were performed by using SAS software, V.9.3 (SAS Institute), and all statistical significance was based on two-side probability.

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics as well as iodine nutrition status for the 1403 participants included in the analysis. The mean age was 9.54 (±0.98) years, the median BMI was 17.05 (IQR 15.55–19.35) kg/m2 and the median UIC was 184.90 µg/L.

Table 1.

General characteristics for children from Shanghai, Haimen and Taizhou, China, in 2014

| Male | Female | |||||

| n | % | n | % | χ2 | p Value | |

| Total | 739 | 52.67 | 664 | 47.33 | ||

| Age (years) | 0.788 | 0.852 | ||||

| 8 | 116 | 15.70 | 111 | 16.72 | ||

| 9 | 246 | 33.29 | 215 | 32.38 | ||

| 10 | 237 | 32.07 | 204 | 30.72 | ||

| 11 | 140 | 18.94 | 134 | 20.18 | ||

| BMI | 11.56 | 0.003 | ||||

| Normal | 531 | 71.85 | 443 | 66.72 | ||

| Overweight | 110 | 14.88 | 145 | 21.84 | ||

| Obese | 98 | 13.26 | 76 | 11.45 | ||

| Area | 6.182 | 0.046 | ||||

| Minhang | 294 | 39.78 | 226 | 34.04 | ||

| Haimen | 234 | 31.66 | 214 | 32.23 | ||

| Yuhuan | 211 | 28.55 | 224 | 33.73 | ||

| UIC (μg/L)* | 4.198 | 0.241 | ||||

| <100 | 122 | 17.35 | 132 | 20.63 | ||

| 100–199 | 282 | 40.11 | 226 | 35.31 | ||

| 200–299 | 171 | 23.14 | 158 | 24.69 | ||

| ≥300 | 128 | 17.32 | 124 | 19.38 | ||

| Iodised salt consumption† | 0.015 | 0.901 | ||||

| No | 250 | 36.39 | 235 | 36.72 | ||

| Yes | 437 | 63.61 | 405 | 63.28 | ||

*A total of 60 missing: 36 (60.00%) were male and 24 (40.00%) were female.

†A total of 76 missing: 52 (68.42%) were male and 24 (31.58%) were female.

BMI, body mass index; UIC, urinary iodine concentration.

TN(s) were detected in 259 children, accounting for 18.46% of all the participants. Most nodules were accompanied by hypoechogenicity. Of the participants, 5.92% (83/1403) had solitary nodule and 12.54% (176/1403) had multiple TNs. The frequency of TNs showed no age-related or sex-related difference (table 2). The median UICs in children without nodules, with single nodule and multiple nodules were 187.80 µg/L, 195.55 µg/L and 160.45 µg/L, respectively (χ2 7.44, p=0.024). The prevalence of multiple TNs was much higher in children consuming non-iodised salt than those consuming iodised salt.

Table 2.

Comparison of the prevalence of thyroid nodules in different subgroups for children from Shanghai, Haimen and Taizhou, China, in 2014

| Characteristics | No nodule | Nodule(s) | |||||

| n | n (%) | Solitary nodule (n (%)) | Multiple nodules (n (%)) | Total | χ2, p Value* | χ2, p Value† | |

| All | 1403 | 1144 (81.54) | 83 (5.92) | 176 (12.54) | 259 (18.46) | ||

| Sex | 3.95, 0.047 | 4.264, 0.119 | |||||

| Male | 739 | 617 (83.49) | 37 (5.01) | 85 (11.50) | 122 (16.51) | ||

| Female | 664 | 527 (79.37) | 46 (6.93) | 91 (13.70) | 137 (20.63) | ||

| Age (years) | 9.11, 0.028 | 11.61, 0.071 | |||||

| 8 | 227 | 192 (84.58) | 12 (5.29) | 23 (10.13) | 35 (15.42) | ||

| 9 | 461 | 359 (77.87) | 34 (7.38) | 68 (14.75) | 102 (22.13) | ||

| 10 | 441 | 374 (84.81) | 24 (5.44) | 43 (9.75) | 67 (15.19) | ||

| 11 | 274 | 219 (79.93) | 13 (4.74) | 42 (15.33) | 55 (20.07) | ||

| Iodised salt consumption‡ | 6.85, 0.009 | 12.46, 0.002 | |||||

| No | 485 | 380 (78.35) | 26 (5.36) | 79 (16.29) | 105 (21.65) | ||

| Yes | 842 | 708 (84.09) | 52 (6.18) | 82 (9.74) | 134 (15.91) | ||

| Urinary iodine (µg/L)§ | 13.00, 0.005 | 18.65, 0.005 | |||||

| ≤100 | 254 | 204 (80.31) | 12 (4.72) | 38 (14.96) | 50 (19.69) | ||

| 100–200 | 508 | 400 (78.74) | 31 (6.10) | 77 (15.16) | 108 (21.26) | ||

| 200–300 | 329 | 268 (81.46) | 25 (7.60) | 36 (10.94) | 61 (18.54) | ||

| >300 | 252 | 225 (89.29) | 12 (4.76) | 15 (5.95) | 27 (10.71) | ||

| Area | 142.11, <0.001 | 155.80, <0.001 | |||||

| Shanghai | 520 | 344 (66.15) | 49 (9.42) | 127 (24.42) | 176 (33.85) | ||

| Haimen | 448 | 426 (95.09) | 20 (4.46) | 2 (0.45) | 22 (4.91) | ||

| Taizhou | 435 | 374 (85.95) | 14 (3.22) | 47 (10.80) | 61 (14.02) | ||

*Comparison between participants with/without thyroid nodule(s).

†Comparison among participants without nodule/with solitary nodule/with multiple nodules.

‡A total of 60 missing: 36 (60.00%) were male and 24 (40.00%) were female.

§A total of 76 missing: 52 (68.42%) were male and 24 (31.58%) were female.

Based on BMI, 255 (18.17%) were overweight and 174 (12.40%) were obese. Girls were more likely to be overweight than boys, and the prevalence of overweight/obese decreased with age in both sexes (p trend: 0.033 for boys and 0.010 for girls). The prevalences of solitary and multiple nodules in overweight subjects were 3.53% (9/255) and 15.29% (39/255), while the corresponding prevalences were 20.48% (17/174) and 14.77% (26/174) in obese ones, respectively.

Multivariable analysis revealed significant associations between obesity and the risk of TN(s) (table 3). As compared with normal-weight children, obese children experienced a significantly higher risks of TN(s) (OR 1.82 (95% CI 1.22 to 2.70)). We observed a similar association of obesity with the risk of either solitary nodule or multiple nodules (table 4). When stratified by sex, only obese girls experienced an increased risk for multiple nodules (OR 2.10 (95% CI 1.03 to 4.31)), but the interaction of obesity with sex was not significant (p=0.494). Associations of multiple nodules with overweight (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.07 to 3.29) and obesity (OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.05 to 3.78) were observed in children aged 8 or 9 years, but not in older ones. Overweight was not significantly associated with solitary TN in general, which might be due to small number of children with this thyroid condition. Overweight children had an increased risk for multiple TNs (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.02) only in iodised salt consumers.

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis of obesity and thyroid nodule(s) for children from Shanghai, Haimen and Taizhou, China, in 2014

| Thyroid nodule(s) | |||||||

| No nodule | Normal | Overweight | Obesity | ||||

| N | N | OR | N | OR (95% CI)* | N | OR (95% CI)* | |

| All subjects† | 1144 | 168 | 48 | 43 | |||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.11 (0.78 to 1.59) | 1.58 (1.07 to 2.31) | ||||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 (0.69 to 1.45) | 1.82 (1.22 to 2.70) | ||||

| Model 3 | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.71 to 1.51) | 1.71 (1.13 to 2.59) | ||||

| Sex‡ | |||||||

| Male | 576 | 80 | 1.00 | 14 | 0.83 (0.45 to 1.54) | 17 | 1.39 (0.77 to 2.52) |

| Female | 512 | 79 | 1.00 | 29 | 1.21 (0.75 to 1.96) | 20 | 2.10 (1.17 to 3.79) |

| Age (years)§ | |||||||

| 8–9 | 519 | 76 | 1.00 | 27 | 1.37 (0.83 to 2.25) | 25 | 1.87 (1.10 to 3.19) |

| 10–11 | 569 | 83 | 1.00 | 16 | 0.77 (0.43 to 1.38) | 12 | 1.39 (0.70 to 2.75) |

| Iodised salt consumption¶ | |||||||

| Yes | 708 | 81 | 1.00 | 28 | 1.20 (0.75 to 1.93) | 25 | 1.62 (0.98 to 2.68) |

| No | 380 | 78 | 1.00 | 15 | 0.81 (0.43 to 1.50) | 12 | 1.94 (0.92 to 4.09) |

*95% confidence interval.

†Model 1, univariate analysis (n=1403); model 2, adjusted for sex, age, iodised salt consumption (n=1327); model 3, adjusted for sex, age, urinary iodine concentration (n=1343).

‡Adjusted for age and iodised salt consumption (n=1327).

§Adjusted for sex and iodised salt consumption (n=1327).

¶Adjusted for sex and age (n=1327).

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis of obesity and solitary and multiple thyroid nodules for children from Shanghai, Haimen and Taizhou, China, in 2014

| Normal | Overweight | Obesity | |||||||||||

| No nodule | Solitary nodule | Multiple nodules | Solitary nodule | Multiple nodules | Solitary nodule | Multiple nodules | |||||||

| N | N | OR | N | OR | N | OR (95% CI)* | N | OR (95% CI)* | N | OR (95% CI)* | N | OR (95% CI)* | |

| All subjects† | 1144 | 57 | 111 | 9 | 39 | 17 | 26 | ||||||

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.62 (0.30 to 1.26) | 1.37 (0.92 to 2.03) | 1.84 (1.04 to 3.25) | 1.44 (0.91 to 2.30) | |||||||

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.53 (0.25 to 1.13) | 1.33 (0.88 to 2.03) | 1.82 (0.99 to 3.36) | 1.62 (0.98 to 2.70) | |||||||

| Model 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.54 (0.25 to 1.16) | 1.24 (0.82 to 1.88) | 2.07 (1.16 to 3.71) | 1.67 (1.03 to 2.70) | |||||||

| Sex‡ | |||||||||||||

| Male | 576 | 26 | 1.00 | 54 | 1.00 | 1 | 0.17 (0.02 to 1.28) | 13 | 1.18 (0.61 to 2.26) | 7 | 1.53 (0.63 to 3.71) | 10 | 1.29 (0.62 to 2.70) |

| Female | 512 | 29 | 1.00 | 50 | 1.00 | 7 | 0.77 (0.33 to 1.82) | 22 | 1.49 (0.86 to 2.59) | 8 | 2.09 (0.89 to 4.89) | 12 | 2.10 (1.03 to 4.31) |

| Age (years)§ | |||||||||||||

| 8–9 | 519 | 29 | 1.00 | 47 | 1.00 | 5 | 0.63 (0.24 to 1.68) | 22 | 1.87 (1.07 to 3.29) | 9 | 1.60 (0.71 to 3.57) | 16 | 2.00 (1.05 to 3.78) |

| 10–11 | 569 | 26 | 1.00 | 57 | 1.00 | 3 | 0.46 (0.14 to 1.55) | 13 | 0.95 (0.50 to 1.82) | 6 | 2.05 (0.80 to 5.25) | 6 | 1.05 (0.43 to 2.60) |

| Iodised salt consumption¶ | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 708 | 35 | 1.00 | 46 | 1.00 | 5 | 0.48 (0.18 to 1.27) | 23 | 1.76 (1.03 to 3.02) | 12 | 1.76 (0.88 to 3.54) | 13 | 1.50 (0.78 to 2.90) |

| No | 380 | 20 | 1.00 | 58 | 1.00 | 3 | 0.59 (0.17 to 2.08) | 12 | 0.88 (0.45 to 1.75) | 3 | 1.84 (0.50 to 6.79) | 9 | 1.97 (0.86 to 4.48) |

*95% confidence interval.

†Model 1, univariate analysis (n=1403); model 2, adjusted for sex, age, iodised salt consumption (n=1327); model 3, adjusted for sex, age, urinary iodine concentration (n=1343).

‡Adjusted for age and iodised salt consumption (n=1327).

§Adjusted for sex and iodised salt consumption (n=1327).

¶Adjusted for sex and age (n=1327).

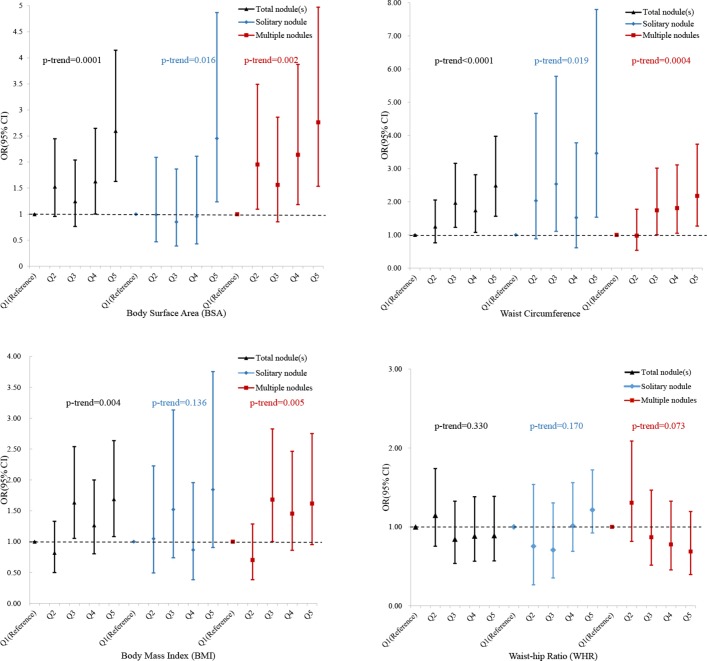

Figure 2 presents multivariate-adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for solitary and multiple TNs associated with the quintiles of BSA, WC, BMI and WHR, respectively. After adjustment for sex, age and iodised salt consumption status, BSA and WC were positively related to the risks of solitary and multiple nodule(s) (p values for trend for all the nodules together were 0.0001 and <0.0001, respectively). As compared with children in the lowest quintile, the ORs of solitary and multiple nodules were 2.45 (95% CI 1.24 to 4.87) and 2.76 (95% CI 1.54 to 4.97) for those in the highest quintile of BSA and 3.46 (95% CI 1.54 to 7.80) and 2.18 (95% CI 1.27 to 3.74) for those in the highest quintile of WC, respectively. The interaction between BSA and sex on TNs was not statistically significant (p interaction: 0.785 for solitary nodule and 0.600 for multiple nodules).

Figure 2.

Associations of different physical measurements (body surface area, waist circumference, body mass index and waist–hip ratio) with thyroid nodule(s) for children from Shanghai, Haimen and Taizhou, China, in 2014.

The results for BMI and WHR were less consistent. BMI was positively associated with the risk of multiple nodules (p trend=0.005), while WHR showed no association with either solitary or multiple nodules.

Discussion

In this large cross-sectional study of children living in iodine-sufficient areas in East China, we observed a high prevalence of TNs and positive associations of obesity with both solitary and multiple TNs. Among several anthropometric measurements, BSA and WC were related to the risks for both solitary and multiple TNs. These findings were generally consistent across sex groups and independent of iodised salt consumption status.

TN(s) is common in adults, and its impact on thyroid cancer risk is still unclear.16 The prevalence of incidental TNs detected by ultrasound examinations is high in adults (close to 50%) as well as in iodine-deficient countries.3–5 However, few studies have investigated the prevalence and the spectrum of appearance of ultrasound-detected findings in children. TNs were identified in 1.65% of children aged 3–18 years in three Japanese prefectures, and the prevalence increased with age with a female predominance.32 The information released by Fukushima Prefecture indicated that 2014 (1.15%) of 75 216 Japanese children aged 0–18 had TNs.33 Avula et al conducted a retrospective analysis in 287 Canadian children (mean age=6.2) and detected only 1 child with multiple TNs but 52 (18%) children with thyroid abnormalities.34 In healthy Greek children living in an iodine-replete area, one or more nodules were observed in 5.1% of them.35 For 2410 children aged 6–17 years living in Hangzhou, China, TNs were detected in 10.66% of them.36 These results showed much lower frequencies than those observed in the current study, in which TNs existed in 18.46% of 1433 Chinese children with little age variations and sex variations. Influencing factors include age composition, interobserver variation, iodine intake, socioeconomic status and individual and/or family history, as well as detection sensitivity and image quality of ultrasound machine.32

TN has multiple known risk factors, including demographic parameters, clinical history, age, sex,6–8 iodine deficiency3 and potentially milk consumption.36 The association between TN(s) and obesity has been explored mostly in adults with inconsistent results.37 38

Obesity is a risk factor for several chronic conditions, as well as goitre in adults.39 Its impact on TNs has also been investigated by using different anthropometric parameters in adults. Among various parameters, BMI was most frequently used as a measure of general adiposity. It has been increasingly recognised that the adverse effects of obesity relate to the amount and to the distribution of excess body fat. Therefore, the use of BMI alone to infer health risks in Asians may underestimate the detrimental health effects of excess adiposity.40 WHR and WC were good proxy measures of central adiposity. It has been suggested that WC is a better marker for total body adiposity than it is for visceral fat.41 Another study has shown that both WC and BMI appear to perform equally well for estimating children and adolescents’s total adiposity.42 BSA is a better indicator of the circulating blood volume, oxygen consumption and basal energy expenditure than BMI37 and has been shown to be the best independent predictor of the thyroid volume in both sexes.

Several studies have found significant associations between measures of obesity and the risk of TNs. For example, a study conducted in Hangzhou, China, observed a prevalence of TN being 34.97% (33.97 for men and 36.92% for women) and great WC as a risk factor for new TN in this iodine-adequate area.2 Similar trends were observed for females and males, but the association was not statistically significant in men,2 which was similar to our findings in children. Another study of postmenopausal women also revealed that WC and BMI were associated with TNs.43 Large BMI was associated with nodule growth among older patients with multiple nodules and larger dominant nodules.17 A study conducted by Shin et al linked thyroid nodular disease to WC for males and glycated haemoglobin for females,44 suggesting potential sex disparity. The presence of insulin resistance was associated with larger thyroid gland volume and an increased prevalence of TNs,45 46 which might be explained by obesity-related subclinical inflammation and an associated increase in levels of insulin-like growth factor-1.45 However, another study yielded conflicting results, which suggested that adult patients with normal weight or overweight based on BMI tended to have an increased risk of TNs, as compared with underweight or obese people.38 Evidence in children had been relatively limited.

The prevalence of obesity and overweight in our study population was slightly higher than that in students from four Chinese megacities (25.6%)47 but lower than urban students of similar age groups in the National Surveys on Chinese Students' Constitution and Health (37.0% for overweight and 20.3% for obesity).48 Our findings of increased risk for TNs in obese children are generally consistent with those in obese adults of other studies. The association of BSA with thyroid volume in children has been well established,35 while its relation to TNs has been seldom explored. Kim et al38 examined 7763 healthy Korean adults and observed a significantly smaller BSA in those with TNs compared with the others, which was opposite to our findings. Considering the great difference in BSA between adults and children, it needs to be cautious to generalise the results to children.16 Xu et al36 conducted a cross-sectional study in Hangzhou, China, and reported an OR of 2.97 (95% CI 1.85 to 4.77) for TNs for children with average BSA or above as compared with those with less than average BSA. However, they did not collect the information on waist and hip circumferences and number of TNs. Therefore, it was not possible to determine different associations between WC, WHR and different kinds of nodules in that study. The potential interactive effects of iodised salt consumption and sex on the association between overweight and multiple nodules also need further investigations with a larger sample size.

The strengths of our study include large sample size, directly measured thyroid ultrasonography and anthropometric measurements following a standardised protocol and the abilities to distinguish solitary and multiple nodules and to adjust for household iodised salt consumption status. Our study has several limitations. First, we did not have any information on thyroid function. Therefore, we were unable to further search potential mechanisms that might explain the observed associations. Second, there were no information on the amount of salt and milk consumption. In the current study, the number of children with solitary or multiple nodules was small in some categories. In addition, the cross-sectional design prevents us from making causal inferences.

Conclusion

In this cross-sectional study of a relatively lean children population, we found that elevated levels of general or abdominal adiposity, measured by BMI, BSA and WC, were associated with a significant increase in the risk of TN(s), especially multiple nodules in girls and solitary nodule in boys. Our findings, along with those observed from adult populations, emphasise the importance of preventing excess adiposity for primary prevention of TNs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NW, HF, CF, PH, MS, QZ and QJ contributed to the study design; NW, HF, CF, PH, MS, FJ, QZ and QJ contributed to data acquisition and collection; NW, QZ and YC contributed to data analysis and interpretation; NW, QZ and YC drafted the manuscript; all authors contributed to the preparation of the final document, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (number 81602806), Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (number 20144Y0104) and Shanghai Key Discipline Construction Project of Shanghai Municipal Public Health (number 15GWZK0801).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ethical review board of the School of Public Health of Fudan University (#2012-03-0350S).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Aydin Y, Besir FH, Erkan ME, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of nodular thyroid diseases detected by ultrasonography in the Western Black Sea region of Turkey. Med Ultrason 2014;16:100–6. 10.11152/mu.2013.2066.162.ya1fhb2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin J, Wang C, Shao Q, et al. Relationship between the prevalence of thyroid nodules and metabolic syndrome in the iodine-adequate area of Hangzhou, China: a cross-sectional and cohort study. Int J Endocrinol 2014;2014:1–7. 10.1155/2014/675796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlé A, Krejbjerg A, Laurberg P. Epidemiology of nodular goitre. Influence of iodine intake. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;28:465–79. 10.1016/j.beem.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajmal S, Rapoport S, Ramirez Batlle H, et al. The natural history of the benign thyroid nodule: what is the appropriate follow-up strategy? J Am Coll Surg 2015;220:987–92. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo H, Sun M, He W, et al. The prevalence of thyroid nodules and its relationship with metabolic parameters in a Chinese community-based population aged over 40 years. Endocrine 2014;45:230–5. 10.1007/s12020-013-9968-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo J, McManus C, Chen H, et al. Are there predictors of malignancy in patients with multinodular goiter? J Surg Res 2012;174:207–10. 10.1016/j.jss.2011.11.1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, et al. Time trends of incidence of age-associated diseases in the US elderly population: Medicare-based analysis. Age Ageing 2013;42:494–500. 10.1093/ageing/aft032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huan Q, Wang K, Lou F, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of thyroid nodules and risk factors for malignant nodules: a retrospective study from 6,304 surgical cases. Chin Med J 2014;127:2286–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin J, Kim MH, Yoon KH, et al. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and thyroid nodules in healthy Koreans. Korean J Intern Med 2016;31:98–105. 10.3904/kjim.2016.31.1.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teng W, Shan Z, Teng X, et al. Effect of iodine intake on thyroid diseases in China. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2783–93. 10.1056/NEJMoa054022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guignard R, Truong T, Rougier Y, et al. Alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking, and anthropometric characteristics as risk factors for thyroid cancer: a countrywide case-control study in New Caledonia. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:1140–9. 10.1093/aje/kwm204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leitzmann MF, Brenner A, Moore SC, et al. Prospective study of body mass index, physical activity and thyroid cancer. Int J Cancer 2010;126:NA–56. 10.1002/ijc.24913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samanic C, Chow WH, Gridley G, et al. Relation of body mass index to cancer risk in 362,552 Swedish men. Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:901–9. 10.1007/s10552-006-0023-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rapp K, Schroeder J, Klenk J, et al. Obesity and incidence of cancer: a large cohort study of over 145,000 adults in Austria. Br J Cancer 2005;93:1062–7. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han JM, Kim TY, Jeon MJ, et al. Obesity is a risk factor for thyroid cancer in a large, ultrasonographically screened population. Eur J Endocrinol 2013;168:879–86. 10.1530/EJE-13-0065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niedziela M. Thyroid nodules. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;28:245–77. 10.1016/j.beem.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durante C, Costante G, Lucisano G, et al. The natural history of benign thyroid nodules. JAMA 2015;313:926–35. 10.1001/jama.2015.0956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaFranchi SH. Inaugural management guidelines for children with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: children are not small adults. Thyroid 2015;25:713–5. 10.1089/thy.2015.0275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang N, Zhou Y, Fu C, et al. Influence of bisphenol A on thyroid volume and structure independent of iodine in school children. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141248 10.1371/journal.pone.0141248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peixin H, Feng J, Xin F, et al. A cross-sectional study of urinary iodine and salt iodine content among schoolchildren and their families in Haimen City, Jiangsu Province. Chinese Journal of Endemiology 2014;6:654–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pu L, Hong F, Na W, et al. Investigation on urinary and salt iodine levels of school-aged children in Minhang District of Shanghai. Fudan University Journal of Medical Sciences 2014;41:179–82. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su M, Wang C, Li S, et al. [A cross-sectional study on urinary iodine and iodine content of salt among school children aged 8-10 years old in Yuhuan County, Zhejiang Province in 2012]. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2013;42:893–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Zong XN, Ji CY, et al. [Body mass index cut-offs for overweight and obesity in Chinese children and adolescents aged 2 - 18 years]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2010;31:616–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosteller RD. Simplified calculation of body-surface area. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1098–98. 10.1056/NEJM198710223171717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuse Y, Saito N, Tsuchiya T, et al. Smaller thyroid gland volume with high urinary iodine excretion in Japanese schoolchildren: normative reference values in an iodine-sufficient area and comparison with the WHO/ICCIDD reference. Thyroid 2007;17:145–55. 10.1089/thy.2006.0209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2009;19:1167–214. 10.1089/thy.2009.0110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Committee of standards for endemic and parasites, Ministry of Health of Peoples republic of China. WS/T107-2006 Method for measuring iodine in urine by As3+-Ce4+ catalytic spectrophotometry. Beijing: China Standard Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong YK HC, Bq L, Mh L, et al. Fu SY General test method in salt industry: determination of iodide ion (GB/T 13025.7-1999). Beijing, China: China Criteria Publishing House 1999:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health of Peoples republic of China. GB160062-2008 Iodine Deficiency Disease elimination standard. Beijing, China: China Standard Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimmermann MB, Andersson M. Assessment of iodine nutrition in populations: past, present, and future. Nutr Rev 2012;70:553–70. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jooste PL, Strydom E. Methods for determination of iodine in urine and salt. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;24:77–88. 10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashida N, Imaizumi M, Shimura H, et al. Thyroid ultrasound findings in children from three Japanese prefectures: Aomori, Yamanashi and Nagasaki. PLoS One 2013;8:e83220 10.1371/journal.pone.0083220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Yasumura S, Hosoya M, Yamashita S, et al. Study protocol for the Fukushima Health Management Survey. J Epidemiol 2012;22:375–83. 10.2188/jea.JE20120105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avula S, Daneman A, Navarro OM, et al. Incidental thyroid abnormalities identified on neck US for non-thyroid disorders. Pediatr Radiol 2010;40:1774–80. 10.1007/s00247-010-1684-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaloumenou I, Alevizaki M, Ladopoulos C, et al. Thyroid volume and echostructure in schoolchildren living in an iodine-replete area: relation to age, pubertal stage, and body mass index. Thyroid 2007;17:875–81. 10.1089/thy.2006.0327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu W, Chen Z, Li N, et al. Relationship of anthropometric measurements to thyroid nodules in a Chinese population. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008452 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cléro E, Leux C, Brindel P, et al. Pooled analysis of two case-control studies in New Caledonia and French Polynesia of body mass index and differentiated thyroid cancer: the importance of body surface area. Thyroid 2010;20:1285–93. 10.1089/thy.2009.0456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JY, Jung EJ, Park ST, et al. Body size and thyroid nodules in healthy Korean population. J Korean Surg Soc 2012;82:13–17. 10.4174/jkss.2012.82.1.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kocak M, Erem C, Deger O, et al. Current prevalence of goiter determined by ultrasonography and associated risk factors in a formerly iodine-deficient area of Turkey. Endocrine 2014;47:290–8. 10.1007/s12020-013-0153-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:902–02. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sardinha LB, Santos DA, Silva AM, et al. A Comparison between BMI, waist circumference, and waist-to-height ratio for identifying cardio-metabolic risk in children and adolescents. PLoS One 2016;11:e0149351 10.1371/journal.pone.0149351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katzmarzyk PT, Bouchard C. Where is the beef? Waist circumference is more highly correlated with BMI and total body fat than with abdominal visceral fat in children. Int J Obes 2014;38:753–4. 10.1038/ijo.2013.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng L, Yan W, Kong Y, et al. An epidemiological study of risk factors of thyroid nodule and goiter in Chinese women. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:11608–20. 10.3390/ijerph120911608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44.Shin J, Kim MH, Yoon KH, et al. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and thyroid nodules in healthy Koreans. Korean J Intern Med 2016;31:98–105. 10.3904/kjim.2016.31.1.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Balkan F, Onal ED, Usluogullari A, et al. "Is there any association between insulin resistance and thyroid cancer? : A case control study". Endocrine 2014;45:55–60. 10.1007/s12020-013-9942-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ayturk S, Gursoy A, Kut A, et al. Metabolic syndrome and its components are associated with increased thyroid volume and nodule prevalence in a mild-to-moderate iodine-deficient area. Eur J Endocrinol 2009;161:599–605. 10.1530/EJE-09-0410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jia P, Li M, Xue H, et al. School environment and policies, child eating behavior and overweight/obesity in urban China: the childhood obesity study in China megacities. Int J Obes 2017;41:813–9. 10.1038/ijo.2017.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Y, Wang S, Zhang Q, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents increased rapidly in Chinese rural regions while level off in urban areas. Int J Cardiol 2016;223:61–2. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.