Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the extent of patient activation and factors associated with activation in adults with comorbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

Renal/diabetes clinics of four tertiary hospitals across the two largest states of Australia.

Study population

Adult patients (over 18 years) with comorbid diabetes and CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Main outcome measures

Patients completed the Patient Activation Measure, the Kidney Disease Quality of Life and demographic and clinical data survey from January to December 2014. Factors associated with patient activation were examined using χ2 or t-tests and linear regression.

Results

Three hundred and five patients with median age of 68 (IQR 14.8) years were studied. They were evenly distributed across socioeconomic groups, stage of kidney disease and duration of diabetes but not gender. Approximately 46% reported low activation. In patients with low activation, the symptom/problem list, burden of kidney disease subscale and mental composite subscale scores were all significantly lower (all p<0.05). On multivariable analysis, factors associated with lower activation for all patients were older age, worse self-reported health in the burden of kidney disease subscale and lower self-care scores. Additionally, in men, worse self-reported health in the mental composite subscale was associated with lower activation and in women, worse self-reported health scores in the symptom problem list and greater renal impairment were associated with lower activation.

Conclusion

Findings from this study suggest that levels of activation are low in patients with diabetes and CKD. Older age and worse self-reported health were associated with lower activation. This data may serve as the basis for the development of interventions needed to enhance activation and outcomes for patients with diabetes and CKD.

Keywords: patient activation, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, self-care, health related quality of life

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Several biological and non-biological patient variables were included as potential factors influencing patient activation since the factors are likely to be multifactorial.

The study was conducted across multiple sites increasing the generalisability of the findings.

The limitations include that our findings may not be generalised to culturally and linguistically diverse populations.

The cross-sectional design of the study did not permit us to assess temporal effects or to rule out the potential for reverse causality with low activation causing poor health.

Introduction

Patient activation may be defined as the ability and willingness of patients to take on the role of managing their own health and healthcare1 and is related to the degree that a patient participates or engages in specific health behaviours.2–4 Previous studies of patients with hypertension in primary care settings suggest that patient activation is associated with patient outcomes, where low activated patients are more likely to smoke,5 have a higher body mass index (BMI) and less likely to achieve cholesterol and glycated haemoglobin targets.6 In patients with diabetes, high activation has been associated with greater engagement in exercise,7 fewer hospitalisations8 and improved glycaemic control.9 In patients with hypertension5 10 11 and chronic kidney disease (CKD)12 high activation is associated with better blood pressure control and in patients with end-stage kidney disease higher activation is likely to improve uptake of home dialysis.13

Low activation levels have been reported in 25%–40% of the general population14 and in patients living with chronic diseases.12 15 16 However, activation levels may vary considerably depending on the severity of the chronic disease.17 18 Indeed, little is known about the activation levels of patients with multiple and complex chronic diseases, including comorbid diabetes and CKD. Among patients with diabetes and CKD, a sufficient degree of activation is required for patients to perform self-management behaviours such as blood glucose monitoring and medication self-management.19 Moreover, as these patients face competing treatment demands especially when treatment recommendations for one condition conflict with or impede management of the other, or when patients prioritise one condition over another,20–22 understanding the degree of patient activation becomes even more important.

Missed opportunities to enhance activation among patients with diabetes and CKD may result in more rapid progression of CKD and development of associated complications.23 Additionally, activation levels may fluctuate as the disease progresses and complications arise necessitating matched changes in activation behaviour.24

Given the importance of patient activation for self-management in people with diabetes and CKD and ultimately patient outcomes, it is important to establish the level of activation in these patients and determine the patient and disease characteristics that influence activation. Consequently, the purpose of the present study was to (1) examine to what degree patients with comorbid diabetes and CKD are activated and (2) identify what modifiable risk factors are independently associated with activation levels in patients with comorbid diabetes and CKD.

Methods

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted (as previously described)25 of patients attending diabetes and renal outpatient clinics of four public tertiary hospitals in Victoria and New South Wales (Monash Health, Alfred Health, Royal North Shore Hospital and Concord Hospital) from January to December 2014. Participants were eligible if they received their usual care at these hospitals and had a diagnosis of diabetes (either type 1 or type 2) and CKD stages 3–5 (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min). The diagnosis of diabetes followed WHO definition26 and was recorded from patients’ prior inpatient or outpatient contacts. Patients were recruited prospectively from clinics and the following questionnaires were completed; the Diabetes Renal Project (Patient Survey), Diabetes Renal Project (Doctors Survey), the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) questionnaire, the Kidney Disease Quality of Life short form (KDQoL-36) and the Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13) (online supplementary appendices 1-5). The Diabetes Renal Project (Patient Survey) (see online supplementary appendix 1) collected demographic information (age, gender, country of birth, language spoken at home) and clinical characteristics such as duration of diabetes and CKD. For each patient the site study staff or the clinician, using standardised procedures that included health assessment templates, also completed a corresponding clinical survey, the Diabetes Renal Project (Doctors Survey) (see online supplementary appendix 2). The questionnaire collected information on patients’ medical history, clinical findings, access to medical care for diabetes and CKD, medications and investigations such as blood test results. All participants were provided with written informed consent and 317 agreed to participate. All local hospital and university human research ethics committees (Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee, Alfred Health Research Ethics Committee, Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee, Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee, Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee and the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee) approved this study.

bmjopen-2017-017695supp001.pdf (94KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017695supp002.pdf (69.3KB, pdf)

Demographic and clinical variables

Age, gender, socioeconomic status (SES), stage of kidney disease, duration of kidney disease and duration of diabetes were all recorded as possible determinants of patient activation. SES was estimated using the Australian Bureau of Statistics data.27 Postcodes were coded according to the Index of Relative Social Disadvantage (IRSD), a composite measure based on selected census variables, which include income, educational attainment and employment status. The IRSD scores for each postcode were then grouped into quintiles for analysis, where the highest quintile comprised 20% of postcodes with the highest IRSD scores (the most advantaged areas).

CKD stage as defined by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) was used to define severity of the disease.28 Duration of CKD was analysed as a continuous variable. eGFR was calculated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (EPI) formula eGFR=141×min(Scr/κ, 1)α×max(Scr/κ, 1)−1.209×0.993Age×1.018×1.159, where Scr is serum creatinine (mg/dL), κ is 0.7 for women and 0.9 for men, α is –0.329 for women and –0.411 for men, min indicates the minimum of Scr/κ or 1 and max indicates the maximum of Scr/κ or 1.29 We used the CKD EPI formula because it is routinely reported in Australia30 as the equation of choice and is recommended by the KDIGO guidelines.31

Self-care

Self-care was assessed by the SDSCA questionnaire,32 which is a self-report measure of how often participants performed diabetes self-care activities (see online supplementary appendix 3). The SDSCA measures several dimensions of diabetes self-management with adequate internal and test–retest reliability, and evidence of validity and sensitivity to change.32 An overall Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.63 has been reported.33 The SDSCA questionnaire has been used in several studies and settings34–36 to evaluate self-care among adults with diabetes. This study used a version of the SDSCA questionnaire that included items assessing five domains of diabetes self-management: general diet (two items), specific diet (two items), exercise (two items), blood glucose testing (two items) and foot care (two items).32 The medication self-management domain was excluded because of its ceiling effects and lack of variability among participants.32 The smoking self-management domain was also excluded because smoking behaviour was relevant to smokers only.

bmjopen-2017-017695supp003.pdf (158KB, pdf)

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the English version of the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life (KDQoL-36) questionnaire (see online supplementary appendix 4), which is a 36-item HRQoL survey with five subscales, namely the 12-item Short Form Health Survey measure of physical and mental functioning, burden of kidney disease, symptom/problems list and the effects of kidney disease subscales.37 Item scores were summed for each scale and transformed on a scale of 0 to 100 with a higher score indicating better HRQoL.29 The validity and reliability of the KDQoL-36 questionnaire has been reported previously.38–40

bmjopen-2017-017695supp004.pdf (25.3KB, pdf)

Patient activation

A 13-item survey-based scale called the short form of the PAM-13 that groups patients along a four-point levelling scale based on how activated patients are was used to measure patient activation (see online supplementary appendix 5). It has similar reliability and validity to the 22-item version across different ages, genders and health condition status (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 and a Rasch person statistic of 0.81 for the real and 0.85 for the model on which it was based).3 41 The validity and reliability of the PAM-13 has also been tested in various regions and in patients with different conditions.42–45 Each item of the form was scored on the five-point Likert response scale. The raw scores were transformed from the original metric to a 0–100 metric with higher scores indicating higher activation levels. Based on the patient activation score, patients were categorised into four levels: level 1 (score <47.0), level 2 (score 47.1–55.1), level 3 (score 55.2–67.0) and level 4 (score >67.0).41 The activation levels were then dichotomised into low activation (levels 1 and 2) and high activation (levels 3 and 4) as reported in previous studies.46 47

bmjopen-2017-017695supp005.pdf (13.2KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Normally distributed data are presented with mean and SD as the measures of central tendency and dispersion, respectively. Correspondingly, non-normally distributed continuous data are presented with median and IQR (thus 25th and 75th percentiles), respectively. All HRQoL subscales were treated as continuous variables. First, the four patient activation levels were dichotomised into low activation group (levels 1 and 2) and high activation group (levels 3 and 4). Second, χ2 or t-tests (as appropriate) were used to analyse differences or associations between patient and disease characteristics and patient activation. Third, using the PAM score as a continuous variable, univariable regression models were performed in which each covariate was controlled for separately to ascertain its potential importance. Covariates that reached a significance level of p<0.10 or were of clinical importance were included in stepwise backward multivariable linear regression models that investigated the factors associated with patient activation for the entire study population and stratified analyses according to gender.48 Potential covariates were age, gender, subscales of HRQoL, eGFR, BMI, SES and the composite self-care score. CIs were reported at the 95% level and for all analyses, a p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Cases with missing values were not included in the analyses after checking for the amount of missing data which was minimal (less than 1%) for variables such as age, eGFR, SES and duration of diabetes and kidney disease. There was no pattern in the missing data on any variables. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS V.22 or Stata V.12.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Patient characteristics

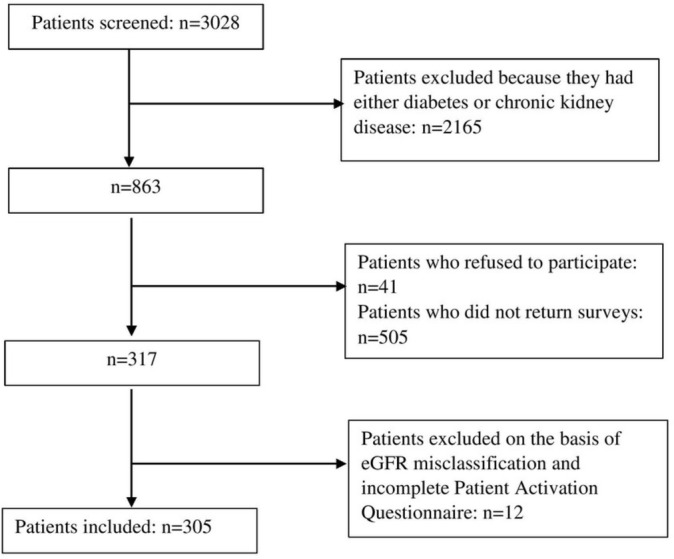

A total of 3028 patients were screened, 317 studied and of those 305 included in the analyses after the exclusion of nine patients who had their eGFR misclassified (>60 mL/min/m2) and three patients who had incomplete PAM data (figure 1). There were no differences in age, gender and stage of kidney disease (for one study site) between patients who participated and those who did not participate in the study (see online supplementary table S1). The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in table 1. The median age and IQR was 68 and 14.8 years, respectively, with 59% of the population being over 68 years old and 30% were women. The patients were evenly distributed across groups defined by SES and stage of kidney disease. Approximately 20% were receiving dialysis treatment.

Figure 1.

Patient inclusion flow diagram. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by activation status (N=305)

| Patient activation status | p Value* | ||

| Low level, N (%) | High level, N (%) | ||

| Age | |||

| <68 years | 68 (49.3) | 88 (53.3) | 0.48 |

| ≥68 years | 70 (50.7) | 77 (46.7) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 42 (30.4) | 51 (30.9) | 0.93 |

| Male | 96 (69.6) | 114 (69.1) | |

| Socioeconomic status,† n (%) | 0.86 | ||

| Upper | 24 (17.4) | 34 (20.6) | |

| Upper middle | 32 (23.2) | 31 (18.8) | |

| Lower middle | 27 (19.6) | 34 (20.6) | |

| Upper lower | 28 (20.3) | 31 (18.8) | |

| Lower | 27 (19.6) | 35 (21.2) | |

| CKD duration in years: mean (SD) | 8.8 (9.6) | 9.2 (11.6) | 0.74 |

| Stage of CKD‡ | 0.86 | ||

| 3a | 30 (21.7) | 42 (25.5) | |

| 3b | 35 (25.4) | 42 (25.5) | |

| 4 | 34 (24.6) | 40 (24.2) | |

| 5 | 39 (28.3) | 41 (24.8) | |

| Diabetes duration in years: mean (SD) | 17.1 (12.0) | 18.2 (11.8) | 0.40 |

| Body mass index: mean, n (%) | |||

| Underweight | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0.60 |

| Healthy weight | 17 (24.3) | 15 (17.4) | |

| Overweight | 21 (30.0) | 23 (26.7) | |

| Obese | 47 (67.1) | 31 (36.0) | |

| Dialysis status | |||

| Current | 29 (21.0) | 30 (18.2) | 0.54 |

| Predialysis | 109 (79.0) | 135 (81.8) | |

| HRQoL: mean (SD) | |||

| Symptom/problem list | 72.0 (17.6) | 75.5 (17.4) | 0.08 |

| Effect of kidney disease | 71.0 (23.5) | 74.1 (23.6) | 0.27 |

| Burden of kidney disease | 55.9 (29.5) | 63.3 (31.9) | 0.04 |

| Physical composite summary | 34.4 (11.3) | 36.0 (11.0) | 0.26 |

| Mental composite summary | 45.5 (10.5) | 48.3 (11.0) | 0.03 |

Data are presented in N (%) unless otherwise indicated.

*T-test for mean differences and X2 test for differences in proportions.

†Socioeconomic status was estimated using the Australian Bureau of Statistics data. Postcodes were coded according to the Index of Relative Social Disadvantage, a composite measure based on selected census variables, which include income, educational attainment and employment status.

‡Stage 5 CKD included patients on dialysis (n=59) and not on dialysis (n=21).

CKD, chronic kidney disease; HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

bmjopen-2017-017695supp006.pdf (85.2KB, pdf)

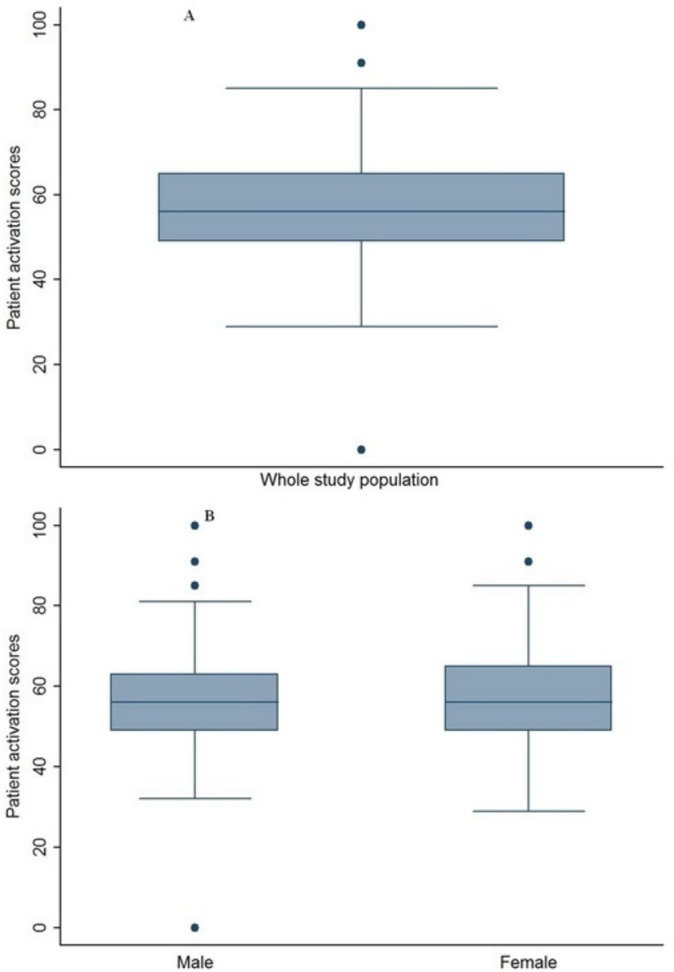

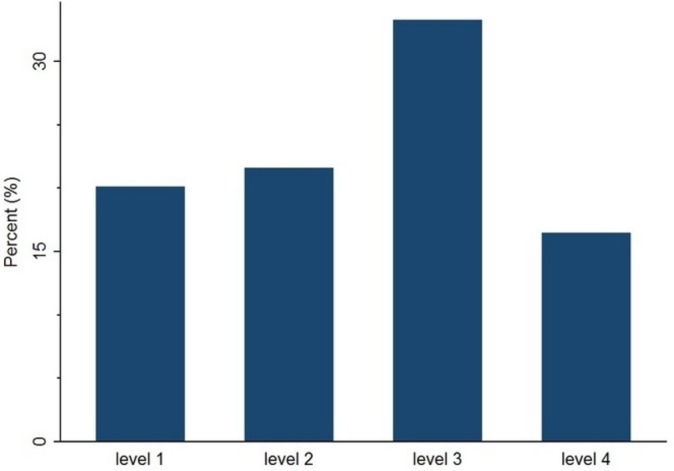

Patient activation scores were normally distributed across the study population (mean 57.6, SD 15.5); male (mean 57.4, SD 16.0) and female patients (mean 58.1, SD 14.4) (figure 2A,B). Twenty-two per cent self-reported PAM level 1, 23.6% level 2, 36.4% level 3 and 18% level 4 (indicating greatest activation) (figure 3). The proportions of the patients with low (levels 1 and 2) and high activation (levels 3 and 4) scores were 46% and 54%, respectively (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Patient activation. Distribution of patient activation from (A) the study population (mean 57.6, SD 15.5) and (B) male (mean 57.4, SD 16.0) and female patients (mean 58.1, SD 14.4).

Figure 3.

Distribution of participants across the four levels of patient activation. Level 1 (score of 0.0–47.0) indicates that a person may not yet understand that their role as a patient is important. Level 2 (47.1–55.1) indicates that a person lacks the confidence and knowledge to take action. Level 3 (55.2–67) indicates that a person is beginning to take action and level 4 (67.1–100) indicates that a person is proactive about health and engages in many recommended health behaviours.

Patients in the low activation group had significantly worse self-reported health in the burden of kidney disease and mental composite summary subscales than patients in the high activation group as shown in table 1 (all p<0.05). No other differences between low and high activation groups were found for demographic factors (age, gender and SES) and disease factors that included stage and duration of CKD, dialysis status, duration of diabetes and BMI (table 1).

Factors associated with patient activation in the study population

On univariable analysis (table 2), factors associated with lower activation were worse self-reported health in all HRQoL subscales, greater renal impairment (lower eGFR) and lower self-care scores. On multivariable analysis, older age, worse self-reported health in the burden of kidney disease subscale and lower self-care scores were independently associated with lower activation (table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable regression model for factors associated with low activation in the study population

| Variables | Univariable B (95% CI) | Multivariable B (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.05 (−0.22 to 0.11) | −0.18 (−0.35 to 0.01)* |

| Gender | ||

| Men | Reference | Reference |

| Women | −0.79 (−4.59 to 3.02) | – |

| Health-related quality of life | ||

| Symptom problem list | 0.15 (0.05 to 0.25)** | – |

| Effects of kidney disease | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.17)* | – |

| Burden of kidney disease | 0.11 (0.05 to 0.16)*** | 0.11 (0.05 to 0.17)*** |

| Physical composite summary | 0.17 (0.01 to 0.33)* | – |

| Mental composite summary | 0.26 (0.09 to 0.42)** | – |

| Duration of diabetes | −0.02 (−0.17 to 0.13) | – |

| Duration of kidney disease | 0.07 (−0.11 to 0.25) | – |

| eGFR† | 0.11 (0.00 to 0.21)* | 0.01 (−0.12 to 0.15) |

| Body mass index | ||

| Healthy weight‡ | Reference | Reference |

| Overweight | −2.78 (−7.75 to 2.20) | – |

| Obese | 1.98 (–2.03 to 5.99) | – |

| Socioeconomic status§ | ||

| Lower | Reference | Reference |

| Lower middle | −0.31 (−4.75 to 4.12) | – |

| Upper lower | −1.42 (−5.80 to 2.95) | – |

| Upper middle | −0.95 (−5.27 to 3.38) | – |

| Upper | 3.17 (−1.28 to 7.62) | – |

| Self-care composite score | 0.21 (0.06 to 0.37)** | 0.18 (0.02 to 0.35)* |

*p<0.05.

**p<0.01.

***p<0.001.

-†Per 1 mL/min increase in eGFR.

‡Due to small numbers of underweight patients (n=2), the underweight group was combined with the healthy weight group for this analysis.

§-Socioeconomic status was estimated using the Australian Bureau of Statistics data. Postcodes were coded according to the Index of Relative Social Disadvantage, a composite measure based on selected census variables, which include income, educational attainment and employment status.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Factors associated with patient activation stratified by gender

Online supplementary tables S2 and S3 show stratified analyses according to gender. On univariable analysis, worse self-reported health in the symptom problems list, burden of kidney disease, mental composite summary subscales and lower self-care scores were associated with lower activation in men. Worse self-reported health in all HRQoL subscales and lower eGFR were associated with lower activation in women. On multivariable analysis, worse self-reported health in the mental composite subscale was independently associated with lower activation in men, and worse self-reported health in the symptom problem list and greater renal impairment (lower eGFR) were independently associated with lower activation in women.

Discussion

Among patients with comorbid diabetes and CKD, we document for the first time in this study that patient activation is low, and identify factors independently associated with lower patient activation. We report significantly worse self-reported health in the burden of kidney disease and mental composite subscales for patients in the low activation group compared with those in the high activation group. Lower activation was also independently associated with older age, having worse self-reported health in the burden of kidney disease subscale and lower self-care scores across the entire study population. In men, worse self-reported health in the mental composite subscale was associated with lower activation. In women, worse self-reported health in the symptom problem list (with symptoms including sore muscles, chest pain, cramps, itchy or dry skin and shortness of breath, faintness/dizziness and lack of appetite) and greater renal impairment were associated with lower patient activation.

The mean patient activation score was 57.6 on a theoretical scale of 0–100 and was comparable to the means cited in several studies across other regions and disease conditions.15 42 49 Patient activation in patients with comorbid diabetes and CKD was generally low with close to 50% of our study population reporting low levels of activation. This is greater than that of the general population where 25%–40% have reported low activation14 and in patients with diabetes where 20%–30% reported low activation.48 50 Conversely in patients with CKD alone (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2), patient activation has been observed to be even lower with over 65% of one study cohort17 reporting low activation levels. Although we expected that diabetes and CKD in combination would lead to lower activation compared with either diabetes or CKD alone, our results suggest higher patient activation among patients with diabetes and CKD. This may be attributed to a focus on self-management of diabetes. More studies are required to confirm this observation.

We found that older age was independently associated with lower activation. Similar findings have been reported in people with diabetes8 16 27 other chronic diseases45 47 51–53 and in a national survey of US adults.54 The reason for this could be a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms and functional difficulties impairing self-management in older patients.51 52 In contrast, other studies in different populations found conflicting evidence, showing no direct relationship between patient activation and age.2 55–57 These inconsistencies may be due to differences in clinical and demographic characteristics of the populations studied. For example, it has been previously reported that younger patients with CKD have poorer coping strategies compared with older patients,58 which may lead to low activation or could possibly be due to low activation. Our results highlight a subgroup at risk of lower activation, which may benefit from targeted interventions to improve activation. These interventions may include encouraging patients to ask questions59 when they attend medical appointments and training their peers to lead such interventions.60 Additionally, the contradictions regarding the relationship between age and patient activation highlight that intervention strategies cannot exclusively be based on the knowledge of patients’ demographics, but should include other modifiable factors as well.

In line with previous studies of patients with conditions other than comorbid diabetes and CKD,15 51 54 61–63 patient activation was low in those with worse self-reported health status. Our study showed that lower mental health composite scores on KDQoL were independently associated with lower patient activation, particularly in men. This could be due to men with comorbid disease having less ability to cope with multiple conditions than women,64 resulting in lower levels of activation. Men with chronic disease may also have less coping ability because they do not seek help as often as women do.65 Given the high prevalence of mental disorders such as depression in patients with CKD,66 addressing mental health issues may be very important for enhancing patient activation and outcomes.

Our data suggest that greater renal impairment in women may be associated with lower activation. The most likely explanation for this is that women tend to have lower physical functioning67 68 which is associated with lower patient activation63 even in the early stages of CKD.17 54 Another plausible explanation is that women may receive less support from their caregivers compared with men due to caregiver stress and fatigue69 associated with managing chronic diseases. The lack of support in managing chronic diseases may lead to lower activation among women. Additionally, due to the complexity of diabetes and CKD, there is limited time to address all patient needs resulting in lower quality medical care for discordant conditions.70

Interestingly, we did not find a significant association between SES and patient activation. This is in contrast to other studies that have reported patient activation to vary by SES with individuals from lower SES groups reported as less activated than those from higher SES groups.6 14 These discordant findings could be attributable to our use of postcode as a surrogate for SES, which may not accurately represent SES.

Strengths and limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in light of the strengths and limitations of our study design. The strengths include the inclusion of several biological and non-biological patient variables such as gender, age, SES, HRQoL, BMI and disease duration as potential factors influencing patient activation since the determinants are likely to be multifactorial. The study was conducted across multiple sites increasing the generalisability of the findings71 and we also used validated and disease-specific instruments for measuring HRQoL (KDQoL-36) and patient activation (PAM-13). The limitations include that our findings may not be generalised to culturally and linguistically diverse populations. The cross-sectional design of the study did not permit assessment of temporal effects or the potential for reverse causality with low activation causing poor health. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the effects over time of factors influencing patient activation in this population.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in patients with comorbid diabetes and CKD patient activation was low, with almost half of patients reporting low activation. Older age and worse self-reported health were associated with lower activation. This data may serve as the basis for the development of interventions needed to enhance activation and outcomes for patients with diabetes and CKD.

bmjopen-2017-017695supp007.pdf (90.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017695supp008.pdf (91KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge S Chaviaras, D Giannopoulos, R McGrath and S Coggan for help in study conduct.

Footnotes

Contributors: EZ, CL and SZ conceptualised the study. EZ, CL, SR and SZ performed data curation. EZ designed the analysis in consultation with CL, SR, GRF, SJ, PGK, KRP, GRF, RGW and SZ. EZ drafted the original draft and all authors reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (NHMRC) Partnership Grant (ID 1055175) between the following health services, research institutes and national consumer stakeholder groups: Alfred Health; Concord Hospital; Royal North Shore Hospital; Monash Health; Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, Monash University; The George Institute for Global Health, University of Sydney; Diabetes Australia; Kidney Health Australia. An Australian Postgraduate Award Scholarship supported CL.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Approval for the Diabetes Renal Project (DRP) was obtained from Monash University, Monash Health, Alfred Health, Royal North Shore Hospital and Concord Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data for the DRP study can be shared for specific research questions that are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1. Hibbard JH, Greene J, Becker ER, et al. . Racial/ethnic disparities and consumer activation in health. Health Aff 2008;27:1442–53. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alegría M, Sribney W, Perez D, et al. . The role of patient activation on patient-provider communication and quality of care for US and foreign born Latino patients. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24 Suppl 3:534–41. 10.1007/s11606-009-1074-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. . Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005–26. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donald M, Ware RS, Ozolins IZ, et al. . The role of patient activation in frequent attendance at primary care: a population-based study of people with chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83:217–21. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim JY, Wineinger NE, Steinhubl SR. The influence of wireless self-monitoring program on the relationship between patient activation and health behaviors, medication adherence, and blood pressure levels in hypertensive patients: a substudy of a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e116 10.2196/jmir.5429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:520–6. 10.1007/s11606-011-1931-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rask KJ, Ziemer DC, Kohler SA, et al. . Patient activation is associated with healthy behaviors and ease in managing diabetes in an indigent population. Diabetes Educ 2009;35:622–30. 10.1177/0145721709335004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Begum N, Donald M, Ozolins IZ, et al. . Hospital admissions, emergency department utilisation and patient activation for self-management among people with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;93:260–7. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Remmers C, Hibbard J, Mosen DM, et al. . Is patient activation associated with future health outcomes and healthcare utilization among patients with diabetes? J Ambul Care Manage 2009;32:320–7. 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181ba6e77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thiboutot J, Stuckey H, Binette A, et al. . A web-based patient activation intervention to improve hypertension care: study design and baseline characteristics in the web hypertension study. Contemp Clin Trials 2010;31:634–46. 10.1016/j.cct.2010.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olomu A, Khan NNS, Todem D, et al. . Blood pressure control in hypertensive patients in federally qualified health centers: impact of shared decision making in the Office-GAP Program. MDM Policy & Pract 2016;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson ML, Zimmerman L, Welch JL, et al. . Patient activation with knowledge, self-management and confidence in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Care 2016;42:15–22. 10.1111/jorc.12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winterbottom A, Bekker H, Mooney A. Dialysis modality selection: physician guided or patient led? Clin Kidney J 2016;9:823–5. 10.1093/ckj/sfw109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hibbard JH, Cunningham PJ. How engaged are consumers in their health and health care, and why does it matter? Res Brief 2008;8:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Skolasky RL, Green AF, Scharfstein D, et al. . Psychometric properties of the patient activation measure among multimorbid older adults. Health Serv Res 2011;46:457–78. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01210.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hendriks M, Rademakers J. Relationships between patient activation, disease-specific knowledge and health outcomes among people with diabetes; a survey study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:393 10.1186/1472-6963-14-393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bos-Touwen I, Schuurmans M, Monninkhof EM, et al. . Patient and disease characteristics associated with activation for self-management in patients with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure and chronic renal disease: a cross-sectional survey study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126400 10.1371/journal.pone.0126400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. The Canadian Diabetes Association. clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trisolini M, Roussel A, Zerhusen E, et al. . Activating chronic kidney disease patients and family members through the Internet to promote integration of care. Int J Integr Care 2004;4:e17 10.5334/ijic.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Al Shamsi S, Al Dhanhani A, Sheek-Hussein MM, et al. . Provision of care for chronic kidney disease by non-nephrologists in a developing nation: a national survey. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010832 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bower P, Harkness E, Macdonald W, et al. . Illness representations in patients with multimorbid long-term conditions: qualitative study. Psychol Health 2012;27:1211–26. 10.1080/08870446.2012.662973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morris RL, Sanders C, Kennedy AP, et al. . Shifting priorities in multimorbidity: a longitudinal qualitative study of patient’s prioritization of multiple conditions. Chronic Illn 2011;7:147–61. 10.1177/1742395310393365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fishbane S, Hazzan AD, Halinski C, et al. . Challenges and opportunities in late-stage chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J 2015;8:54–60. 10.1093/ckj/sfu128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holman H, Lorig K. Patients as partners in managing chronic disease. Partnership is a prerequisite for effective and efficient health care. BMJ 2000;320:526–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lo C, Ilic D, Teede H, et al. . The perspectives of patients on health-care for Co-Morbid Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0146615 10.1371/journal.pone.0146615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: Report of a WHO/IDF Consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Agrawal V, Jaar BG, Frisby XY, et al. . Access to health care among adults evaluated for CKD: findings from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Am J Kidney Dis 2012;59(Suppl 2):S5–15. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2012;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Resnick HE, Foster GL, Bardsley J, et al. . Achievement of American Diabetes Association clinical practice recommendations among U.S. adults with diabetes, 1999-2002: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care 2006;29:531–7. 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnson DW, Jones GR, Mathew TH, et al. . Chronic kidney disease and automatic reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: new developments and revised recommendations. Med J Aust 2012;197:224–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andrassy KM. Comments on ’KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease'. Kidney Int 2013;84:622–3. 10.1038/ki.2013.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 2000;23:943–50. 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schmitt A, Gahr A, Hermanns N, et al. . The Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ): development and evaluation of an instrument to assess diabetes self-care activities associated with glycaemic control. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:138 10.1186/1477-7525-11-138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Freitas S, Freitas da Silva G, Neta D, et al. . Analysis of the self-care of diabetics according to by the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Questionnaire (SDSCA) Acta Scientiarum Health Sciences. Health Science 2014;36:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jalaludin M, Fuziah M, Hong J, et al. . Reliability and validity of the Revised Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) for Malaysian children and adolescents. Malays Fam Physician 2012;7:10–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. AlJohani KA, Kendall GE, Snider PD. Psychometric Evaluation of the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities-Arabic (SDSCA-Arabic): Translation and Analysis Process. J Transcult Nurs 2016;27 10.1177/1043659614526255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hareri HA AM. Assessments of adherence to hypertension medications and associated factors among patients attending tikur anbessa specialized hospital renal unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2012. Int J Nurs Sci 2013;3:6. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chow SK, Tam BM. Is the kidney Disease Quality of Life-36 (KDQOL-36) a valid instrument for Chinese dialysis patients? BMC Nephrol 2014;15:199 10.1186/1471-2369-15-199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ricardo AC, Hacker E, Lora CM, et al. . Validation of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form 36 (KDQOL-36) US Spanish and English versions in a cohort of Hispanics with chronic kidney disease. Ethn Dis 2013;23:202–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chao S, Yen M, Lin TC, et al. . Psychometric Properties of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life-36 Questionnaire (KDQOL-36™). West J Nurs Res 2016;38:1067–82. 10.1177/0193945916640765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, et al. . Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918–30. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rademakers J, Nijman J, van der Hoek L, et al. . Measuring patient activation in The Netherlands: translation and validation of the American short form Patient Activation Measure (PAM13). BMC Public Health 2012;12:577 10.1186/1471-2458-12-577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zill JM, Dwinger S, Kriston L, et al. . Psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM13). BMC Public Health 2013;13:1027 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Prey JE, Qian M, Restaino S, et al. . Reliability and validity of the patient activation measure in hospitalized patients. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:2026–33. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Graffigna G, Barello S, Bonanomi A, et al. . Measuring patient activation in Italy: translation, adaptation and validation of the Italian version of the patient activation measure 13 (PAM13-I). BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2015;15:109 10.1186/s12911-015-0232-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Aung E, Donald M, Williams GM, et al. . Joint influence of patient-assessed chronic illness care and patient activation on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. Int J Qual Health Care 2015;27:117–24. 10.1093/intqhc/mzv001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ahn YH, Kim BJ, Ham OK, et al. . Factors associated with patient activation for self-management among community residents with Osteoarthritis in Korea. J Korean Acad of Nurs 2015;26:303–11. 10.12799/jkachn.2015.26.3.303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hendriks SH, Hartog LC, Groenier KH, et al. . Patient activation in type 2 diabetes: does it differ between Men and Women? J Diabetes Res 2016;2016:1–8. 10.1155/2016/7386532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nijman J, Hendriks M, Brabers A, et al. . Patient activation and health literacy as predictors of health information use in a general sample of Dutch health care consumers. J Health Commun 2014;19:955–69. 10.1080/10810730.2013.837561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Aung E, Donald M, Coll JR, et al. . Association between patient activation and patient-assessed quality of care in type 2 diabetes: results of a longitudinal study. Health Expect 2016;19:356–66. 10.1111/hex.12359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Blakemore A, Hann M, Howells K, et al. . Patient activation in older people with long-term conditions and multimorbidity: correlates and change in a cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:582 10.1186/s12913-016-1843-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gleason KT, Tanner EK, Boyd CM, et al. . Factors associated with patient activation in an older adult population with functional difficulties. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1421–6. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ryvicker M, Feldman PH, Chiu YL, et al. . The role of patient activation in improving blood pressure outcomes in Black patients receiving home care. Med Care Res Rev 2013;70:636–52. 10.1177/1077558713495452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smith SG, Pandit A, Rush SR, et al. . The role of patient activation in preferences for shared decision making: results from a National Survey of U.S. Adults. J Health Commun 2016;21:67–75. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1033115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Do V, Young L, Barnason S, et al. . Relationships between activation level, knowledge, self-efficacy, and self-management behavior in heart failure patients discharged from rural hospitals. F1000Res 2015;4:150 10.12688/f1000research.6557.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fowles JB, Terry P, Xi M, et al. . Measuring self-management of patients' and employees' health: further validation of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) based on its relation to employee characteristics. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:116–22. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lubetkin EI, Lu WH, Gold MR. Levels and correlates of patient activation in health center settings: building strategies for improving health outcomes. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;21:796–808. 10.1353/hpu.0.0350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Abdel-Kader K, Myaskovsky L, Karpov I, et al. . Individual quality of life in chronic kidney disease: influence of age and dialysis modality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:711–8. 10.2215/CJN.05191008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Deen D, Lu WH, Rothstein D, et al. . Asking questions: the effect of a brief intervention in community health centers on patient activation. Patient Educ Couns 2011;84:257–60. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, et al. . The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Res 2010;118:264–70. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Magnezi R, Glasser S, Shalev H, et al. . Patient activation, depression and quality of life. Patient Educ Couns 2014;94:432–7. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hadgkiss EJ, Jelinek GA, Taylor KL, et al. . Engagement in a program promoting lifestyle modification is associated with better patient-reported outcomes for people with MS. Neurol Sci 2015;36:845–52. 10.1007/s10072-015-2089-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mosen DM, Schmittdiel J, Hibbard J, et al. . Is patient activation associated with outcomes of care for adults with chronic conditions? J Ambul Care Manage 2007;30:21–9. 10.1097/00004479-200701000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chamie K, Connor SE, Maliski SL, et al. . Prostate cancer survivorship: lessons from caring for the uninsured. Urol Oncol 2012;30:102–8. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cheshire A, Peters D, Ridge D. How do we improve men’s mental health via primary care? An evaluation of the Atlas Men’s Well-being Pilot Programme for stressed/distressed men. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:13 10.1186/s12875-016-0410-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Toto RD, et al. . Prevalence of major depressive episode in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;54:424–32. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mujais SK, Story K, Brouillette J, et al. . Health-related quality of life in CKD Patients: correlates and evolution over time. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1293–301. 10.2215/CJN.05541008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zimbudzi E, Lo C, Ranasinha S, et al. . Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with co-morbid diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. PLoS One 2016;11:e0168491 10.1371/journal.pone.0168491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007;62:P126–37. 10.1093/geronb/62.2.P126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care 2006;29:725–31. 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gold JL, Dewa CS. Institutional review boards and multisite studies in health services research: is there a better way? Health Serv Res 2005;40:291–308. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00354.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017695supp001.pdf (94KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017695supp002.pdf (69.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017695supp003.pdf (158KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017695supp004.pdf (25.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017695supp005.pdf (13.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017695supp006.pdf (85.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017695supp007.pdf (90.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017695supp008.pdf (91KB, pdf)