Abstract

Spiroketals are key structural motifs found in diverse natural products with compelling biological activities. However, stereocontrolled synthetic access to spiroketals, independent of their inherent thermodynamic preferences, is a classical challenge in organic synthesis that has limited in-depth biological exploration of this intriguing class. Herein, we review our laboratory’s efforts to advance the glycal epoxide approach to the stereocontrolled synthesis of spiroketals via kinetically controlled spirocyclization reactions. This work has provided new synthetic methodologies with applications in both diversity- and target-oriented synthesis, fundamental insights into structure and reactivity, and efficient access to spiroketal libraries and natural products for biological evaluation.

Keywords: catalysis, diversity-oriented synthesis, glycal epoxide, kinetic spiroketalization, spiro compounds

1. Introduction

Spiroketals are found in a wide range of natural products with diverse biological activities.1 This motif can serve both as a pharmacophore that directly engages in specific interactions with biological targets as well as a rigid scaffold that presents side chains along well-defined vectors in three-dimensional space. Prominent examples of the spiroketal pharmacophores include olean, sex pheromones of the olive fruit fly Dacus oleae, wherein the R enantiomer is active on the male while the S enantiomer is active on the female;2 and the avermectin family of antiparasitic agents, in which the spiroketal motif engages in specific binding interactions with glutamate-gated chloride channels (Figure 1).3 Scaffolding functions are seen in calyculin A, a protein phosphatase inhibitor that directs its phosphate, cationic, and hydrophobic side chains into complementary binding sites in the enzyme;4 and bistramide A, an actin disruptor in which the spiroketal acts as a saddle-like 90° turn element.5 Indeed, these scaffolding capabilities of spiroketals have been leveraged in medicinal chemistry to develop potent, stereochemistry-dependent NK1 receptor antagonists as antiemetics with CNS activity in a mouse model.6 A variety of benzannulated spiroketal natural products have also been identified, such as the rubromycin telomerase inhibitors, in which the central spiroketal motif is essential to activity, and related heliquinomycin DNA helicase inhibitors.7

Figure 1.

Spiroketals are found in a wide range of natural products as well as synthetic compounds with diverse biological activities, serving as both binding pharmacophores and rigid scaffolds.

As a result of these diverse biological activities, as well as the intriguing stereochemical and stereoelectronic features of spiroketals,8 this class has long attracted the attention of synthetic chemists, and several excellent reviews have been published previously.1,9 Readers are referred to those articles for comprehensive discussion and review of the field. Herein, we summarize our laboratory’s efforts to develop novel, stereocontrolled approaches to spiroketals, with applications in both diversity-oriented synthesis and natural product total synthesis. In addition to providing efficient access to these molecules for biological evaluation, this program has led to new synthetic methods of broad potential utility and fundamental insights into structure and reactivity.

2. The Glycal Epoxide Approach to Stereocontrolled Synthesis of Spiroketals

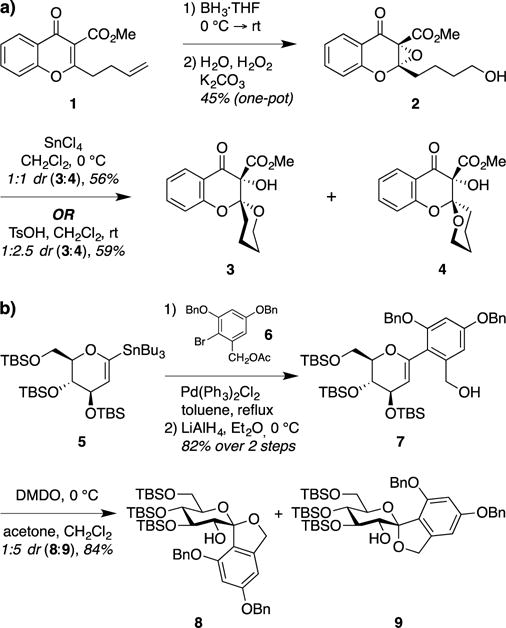

At the outset of our studies, we were inspired by two early reports of the synthesis of spiroketals by spirocyclization of cyclic epoxides having alcohol side chains. Cremins and Wallace reported the synthesis of chromanone spiroketals 3 and 4 by spirocyclizations of chromenone epoxide 2 in 1986 (Figure 2a).10 Subsequently, Friesen and Sturino described a related approach to access the spiroketal core of the papulacandin natural products (9), via treatment of a glycal substrate 7 with dimethyldioxirane (DMDO)11 followed by spontaneous spirocyclization of the intermediate glycal epoxide (Figure 2b).12 In both cases, the spirocyclization reactions proceeded under kinetic control, but afforded mixtures of anomeric diastereomers.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of spiroketals by spirocyclization of cyclic epoxides. (a) Wallace and Cremins’ synthesis of spiroketals from a chromenone epoxide. (b) Friesen and Sturino’s synthesis of the spiroketal core of the papulacandins via DMDO epoxidation of a glycal.

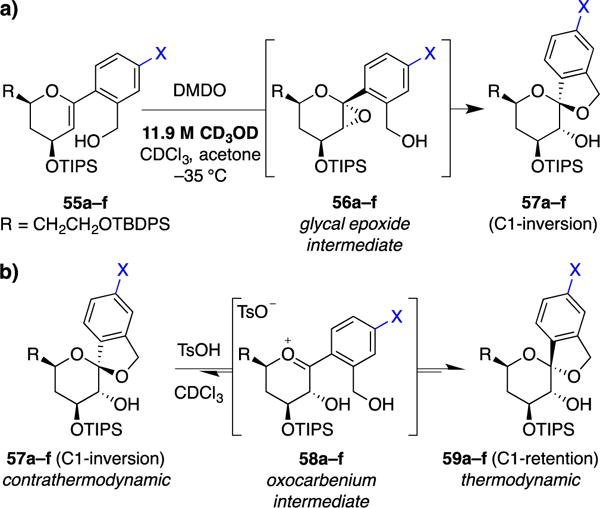

Thus, building upon these reports, we envisioned that the development of kinetic spirocyclization reactions that proceed with either inversion (13) or retention (14) of configuration of epoxides 12 would provide stereocontrolled access to either spiroketal anomer individually (Figure 3), and ideally independently of thermodynamic product stability considerations that govern the stereochemical outcome of classical acid-catalyzed spiroketalization reactions.1,8 In the context of diversity-oriented synthesis, systematic stereochemical diversification at neighboring carbons would then provide access to collections of spiroketals with a wide range of three-dimensional structures.

Figure 3.

The glycal epoxide approach to stereocontrolled spiroketal synthesis using stereocomplementary kinetic spirocyclization reactions. * = site of potential stereochemical diversity.

2.1. Enantioselective synthesis of threo- and erythro-glycal substrates

Toward this end, we first developed asymmetric syntheses of all four diastereomers of the requisite glycal substrates, in which the C3-alcohol substituent would be used as a directing group to control the stereochemistry of the epoxidation reaction. The threo-glycal substrates 18 were readily accessed via asymmetric hetero-Diels–Alder reaction of protected aldehyde 15 with the Danishefsky diene,13 using Jacobsen’s chromium iminoindanol catalyst 1614 (Figure 4a).15 The C5-hydroxyethyl side chain was designed to maintain 1,3-polyol spacing of oxygen functionalities seen in polyketide natural products, with the TBDPS protecting group envisioned as a surrogate for an analogous silyl linker that we developed for solid-phase synthesis applications,16 or as a handle for tagging of the final products with various reporter groups for biological studies. Luche reduction of the ketone proceeded with complete diastereoselectivity for the threo configuration to afford 18.17

Figure 4.

Enantioselective synthesis of (a) threo-glycal (18) and (b) erythro-glycal (24) substrates.

Efforts to access the C3-epimeric erythro-glycals 24 by inversion of the C3-alcohol in the threo-glycals above using a variety of classical approaches were unsuccessful.18 Thus, we turned to an alternative approach involving asymmetric synthesis of an alkynediol substrate 23 followed by alkynol cycloisomerization (Figure 4b). Initial stereoinduction was achieved using asymmetric allylation of aldehyde 15 using Leighton’s chiral allylsilane reagent 1919 followed by homologation to install the desired terminal alkyne in 23. McDonald’s tungsten-mediated photocycloisomerization20 then afforded the desired erythro-glycals 24.

2.2. Installation of C1-alkyl side chains on the glycal substrates

Next, we sought to install C1-alkyl side chains bearing protected alcohol nucleophiles on these glycal substrates. Direct base-mediated alkylation with alkyl iodides proved challenging due to the poor nucleophilicity and high basicity of the corresponding C1-lithioglycals, which led to competing elimination of the alkyl iodide partners.21 To overcome this problem, we developed an alternative approach involving conversion of glycals 25 to the corresponding C1-iodides 27 followed by B-alkyl Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling with alkene-derived side chains to afford a variety of C1-alkylated products 29 (Figure 5).21 In the course of this work, we found that preincubation of the 9-BBN-derived alkyl borane intermediate with aqueous NaOH was critical to avoid competing protodemetallation regenerating 25, which we attributed to disproportionation of an undesired glycal palladium hydroxide intermediate.

Figure 5.

C1-alkylation of glycals via B-alkyl Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of glycal iodides with alkene-derived side chains.

2.3. Methanol-induced kinetic spirocyclization with inversion of configuration

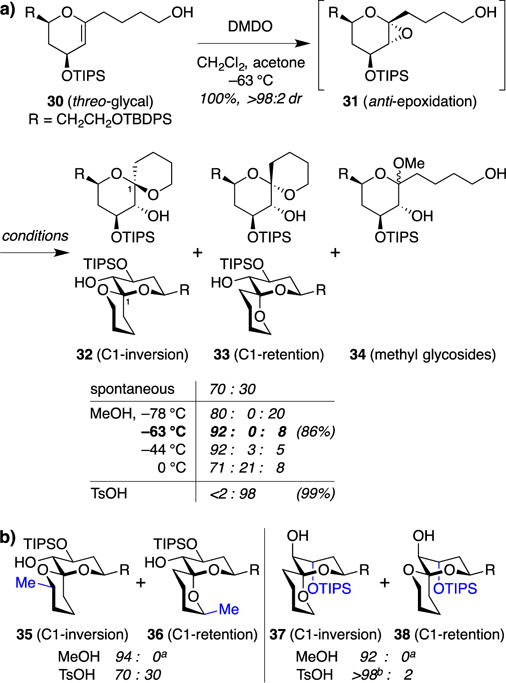

With efficient synthetic access to a variety of glycal substrates in hand, we next explored approaches to achieve kinetic spirocyclization of the corresponding glycal epoxides 12 (Figure 3). We focused our initial efforts on epoxide opening with inversion of configuration. At the outset, we recognized several challenges in achieving such reactivity: (1) SN2 inversion was expected to be challenging at the quaternary anomeric center, (2) competing SN1 reaction manifolds via oxocarbenium intermediates would remove the C1 stereocenter and could lead to poor stereoselectivity or other undesired products, and (3) unfavorable net trans-diequatorial epoxide opening would be required in some cases. Nonetheless, initial studies yielded promising results, with threo-glycal 30 undergoing efficient anti-epoxidation with DMDO to form epoxide intermediate 31, followed upon warming to room temperature by spontaneous spirocyclization to a 70:30 mixture of spiroketals 32 and 33 (Figure 6a).15 Notably, the “inversion” spiroketal 32, which has only a single anomeric stabilization, was formed with equatorial installation of the side chain nucleophile. This is in contrast to most previously reported approaches to monoanomeric spiroketals, which rely upon axial attack.22 Equilibration of this mixture with TsOH yielded exclusively the “retention” spiroketal 33 (99%, >98:2 dr), which is thermodynamically favored due to double anomeric stabilization.

Figure 6.

Discovery of a methanol-induced kinetic spirocyclization with inversion of configuration. (a) Epoxidation of threo-glycal 30 (derived from the corresponding side chain acetate, not shown) and MeOH-induced spirocyclization provides contra-thermo-dynamic inversion spiroketal 32. (b) Examples of threo-series (left) and erythro-series (right) spiroketals in which TsOH equilibration does not favor the stereocomplementary retention product. a Remainder methylglycosides (cf. 34). b C3-desilylated product recovered.

Encouraged by these results, we sought to improve the stereoselectivity of this reaction for the contrathermodynamic inversion spiroketal 32. In a key control experiment, we added a large excess of MeOH to the nascent glycal epoxide 31 at –78 °C in an effort to evaluate the stereochemical outcome of the corresponding intermolecular glycosylation. However, we were surprised to discover that the major product was the inversion spiroketal 32 (80%), formed with complete diastereo-selectivity, while the expected methyl glycosides 34 were formed only as minor products (20%, ≈1:1 dr). Building upon this serendipitous discovery, we found that selectivity for the intramolecular spirocyclization could be improved further to 92:8 (32:34) by adding the MeOH at –63 °C (dry ice/chloroform), consistent with entropic considerations, while higher temperatures led to decreased diastereoselectivity in spiroketal formation. Control experiments indicated that the reaction proceeds under kinetic control and that the methyl glycosides are not intermediates en route to the spiroketals. Surprisingly, use of more hindered alcohols led to increased competing intermolecular glycosylation, as did decreasing the concentration of the alcohol. A mechanistic explanation for these seemingly paradoxical findings was not immediately apparent, and would await future mechanistic studies (vide infra).

Using these optimized reaction conditions, we examined the scope of this MeOH-induced kinetic spirocyclization. Spirocyclization of threo-glycal substrates was effective in forming both 5- and 6-membered rings with inversion of configuration, but not 7-membered rings, with only the corresponding methyl glycosides recovered. Importantly, secondary alcohol side chains also underwent efficient spirocyclization independent of side chain stereochemistry to afford substituted spiroketals that access distinct three-dimensional vectors. The MeOH-induced spirocyclization was also effective in the corresponding erythro-glycal series, albeit with slightly reduced stereoselectivity in 5-membered ring cyclizations.

In some cases, we were also able to access the diastereomeric retention spiroketals (e.g., 33) by thermodynamic equilibration with TsOH. However, this was not the case for many substituent patterns for which the kinetic spirocyclization products were also thermo-dynamically favored, particularly in the erythro-series (Figure 6b). This highlighted the need for a second, kinetically-controlled spirocyclization reaction to access retention spiroketals in a stereocontrolled fashion.

2.4. Ti(Oi-Pr)4-mediated kinetic spirocyclization with retention of configuration

We next sought to develop a stereocomplementary kinetic spirocyclization that proceeded with retention of configuration at the anomeric carbon. We recognized that this could be particularly challenging in the erythro-series for both thermodynamic and kinetic reasons. The acid equilibration studies above indicated that the inversion products are thermodynamically favored in most cases, due to double anomeric stabilization. Furthermore, the erythro-glycal epoxides would be expected to have a kinetic preference for trans-diaxial epoxide opening to give inversion products. We noted parallels to the key challenges in the synthesis of β-mannosides. This problem has been solved elegantly by using covalent tethers to deliver nucleophiles syn to the axial C2-hydroxyl of mannose.23 Accordingly, we hypothesized that a similar tethering effect could be invoked in the spirocyclization of glycal epoxides using a multidentate Lewis acid to coordinate both the epoxide oxygen and side chain hydroxyl (39), thus activating the epoxide to promote oxocarbenium formation (40) while chelating the pendant nucleophile to direct syn addition with retention of configuration at the anomeric carbon (41) (Figure 7a).24

Figure 7.

Discovery of a Ti(Oi-Pr)4-mediated kinetic spirocyclization with retention of configuration. (a) Mechanistic hypothesis for Lewis acid-tethered epoxide opening spirocyclization. (b) Epoxidation of erythro-glycal 42 and Ti(Oi‐Pr)4-mediated spirocyclization provides contra-thermo-dynamic retention spiroketal 38. a C3-desilylated product recovered.

In initial studies with erythro-glycal 42, anti-epoxidation with DMDO proceeded efficiently to give glycal epoxide 43, which spontaneously cyclized even at low temperatures (NMR, –65 °C) to favor the inversion spiroketal 37 (75:25 dr) (Figure 7b).24 In hopes of reversing this stereoselectivity, we added various multidentate Lewis acids directly to the nascent epoxide 43 at –78 °C, followed by warming to room temperature. We were encouraged to find that all of the Lewis acids tested improved the ratio towards the desired retention spiroketal 38. After some optimization, addition of Ti(Oi-Pr)4 (2 equiv.) to the nascent epoxide 43 at –78 °C and warming to 0 °C provided retention spiroketal 38 in 81% yield and complete diastereoselectivity.

Exploration of the scope of this reaction revealed that spirocyclizations of stereochemically diverse substrates in both the erythro and threo series proceed effectively. In particular, the reaction provided contrathermodynamic 5- and 6-membered ring products with complete stereocontrol for retention of configuration and in good yields, including cases in which spiroketals exhibited no anomeric stabilization. Seven-membered rings were also formed stereoselectively, albeit in low yields. Conformational analysis of early (half-chair) and late (chair/boat) transition state models suggested that the observed stereochemical outcome could not be rationalized by alternate, non-chelated mechanisms, nor by a double-inversion mechanism proceed-ing via an intermediate isopropyl glycoside.

Collectively, this Ti(Oi-Pr)4-mediated spirocyclization (C1-retention) and the MeOH-induced spirocyclization (C1-inversion) described in the preceding section provide stereocomplementary, kinetically-controlled access to diastereomeric spiroketals. This enabled the synthesis of pilot-scale libraries that were submitted to the NIH Molecular Libraries Program for biological evaluation, and also set the stage for extension to the stereocontrolled synthesis of benzannulated spiroketals below.

3. Extension of Glycal Epoxide Approach to Benzannulated Spiroketals

Benzannulated spiroketals are important structural motifs found in a variety of natural products with diverse biological activities. This privileged scaffold can bind to multiple classes of biological targets, and importantly, the aromatic ring can impact activity, three-dimensional conformation, and physicochemical properties compared to aliphatic spiroketals. As such, this class is an attractive target for diversity-oriented synthesis of natural product-based libraries for discovery screening. Building upon our earlier discoveries of stereocomplementary kinetically controlled spirocyclizations of glycal epoxides above, we sought to extend this approach to the synthesis of benzannulated spiroketals.

To access the requisite C1-functionalized glycal substrates, we devised an efficient synthetic approach that was amenable to systematic structural diversification in which the aryl moiety could be positioned anywhere along the side chain (Figure 8a). C1-Functionalization of threo- and erythro-glycal stannanes 44 was achieved by direct Stille cross-couplings of aryl and benzyl bromides, or via B-alkyl Suzuki–Miyaura cross-couplings of the corresponding glycal iodides with styrenes and allylbenzenes.25 Deacetylation then provided glycal precursors 45 with the aromatic ring systematically positioned along the side chain to give all possible iterations of 5-, 6-, and 7-membered rings. With these glycal precursors in hand, we set out to evaluate thermodynamic and kinetic spirocyclizations to form benzannulated spiroketals 47 and 48.

Figure 8.

Stereocontrolled synthesis of benzannulated spiroketals. (a) Stille and B-alkyl Suzuki–Miyaura cross couplings were used to install various arene-containing C1 side chains, followed by epoxidation and kinetic spirocyclization. (b) Conformational analysis of diastereomeric benzannulated spiroketals. * = site of stereochemical diversity.

Stereoselective anti-epoxidation of glycals 45 with DMDO afforded glycal epoxide intermediates 46, which were subjected to various spirocyclization conditions in situ. Acid-catalyzed cyclization with TsOH (–78 to 0 °C) led exclusively to the thermodynamic retention spiroketals 48 in all cases, although these reactions often suffered from formation of side products, particularly in the erythro-series, which was prone to Ferrier-type elimination pathways. In contrast, our Ti(Oi-Pr)4-mediated spirocyclization24 provided all 36 retention spiroketals 48 with complete stereocontrol and in high yields (81–99%), demonstrating the mild nature of this reaction. Notably, in stark contrast to the corresponding aliphatic systems, 7-membered rings formed efficiently due to the conformational constraint conferred by the aromatic ring.

On the other hand, our MeOH-induced spirocyclization15 provided stereocontrol for the contra-thermo-dynamic inversion products 47 in only a few cases. Despite the reduced diastereoselectivity, we noted several important reactivity trends. The aromatic ring constraint allowed formation of several 7-membered rings (n+m = 3), while no cyclization was observed for the corresponding aliphatic systems. Attempted cyclizations of C1-aryl substrates (n = 0) resulted in lower stereoselectivity for inversion of configuration, potentially due to stabilization of an oxocarbenium intermediate that can lead to retention products 48. Reduced selectivity and increased methyl glycoside formation was also observed for phenolic substrates (m = 0), which we attributed to the lower nucleophilicity of the phenol side chains.

With these reactivity trends in mind, we explored alternative Brønsted acids and discovered that treatment of the glycal epoxides 46 with AcOH (10 equiv.) provided increased diastereoselectivity for the desired inversion spiroketals 47 in both the 7-membered ring (n+m = 3) and phenolic (m = 0) systems. This was attributed to the absence of competing intermolecular glycosylation in the 7-membered ring systems, and increased epoxide activation in the less-reactive phenol systems. While diastereoselectivities remained modest, the spiroketal products could be separated chromatographically to afford serviceable yields of 32 out of the 36 targeted inversion spiroketals 47.

To evaluate the impact of the aromatic ring upon the conformations of the benzannulated spiroketal products, we carried out detailed structural analyses of several products (Figure 8b). This revealed that both threo-series diastereomers 49 and 50 adopted the standard 4C1 conformation of the non-benzannulated ring, despite the axial orientation of the aromatic ring in inversion spiroketal 49. In contrast, in the corresponding erythro-series products, the retention spiroketal 52 adopted a 1C4 conformation to avoid 1,3-diaxial interactions between the aromatic ring and the C3-OTIPS group. The thermodynamic preference (TsOH) for 52 was attributed to a non-obvious steric interaction in 51 (R′ = OTIPS) between the ortho-proton of the aromatic ring and the axial C2-hydroxyl group. Strikingly, the thermodynamic preference was reversed after desilylation of the C3-OTIPS group, attributed to a favorable intramolecular hydrogen bond in 51 (R′= H).

These systematic studies underscored the distinctive effects of the aromatic ring on reactivity, conformation, and thermodynamic preferences of benzannulated spiroketals. This chemistry was used to synthesize pilot-scale libraries for the NIH Molecular Libraries Program and also paved the way to further mechanistic studies of the MeOH-induced kinetic spirocyclization below.

4. Mechanism of MeOH-catalyzed Kinetic Spirocyclization

We next turned our attention to investigating the mechanistic basis for our novel MeOH-induced kinetic spirocyclization with inversion of configuration, described above (Figure 6).15 We had previously confirmed that the reaction proceeds under kinetic control, as exposure of thermodynamically favored retention spiroketal 33 to the reaction conditions did not generate the contra-thermo-dynamic inversion spiroketal 32. In addition, we had ruled out nucleophilic catalysis by MeOH as a potential mechanism, as reexposure of methyl glycoside side products 34 to the reaction conditions did not yield spiroketals. Finally, addition of other polar aprotic solvents did not induce spirocyclization of epoxide 31, suggesting that the reaction is not driven simply by solvent polarity effects. Based on these experimental observations, we postulated that the kinetic spirocyclization reaction might proceed via MeOH hydrogen-bonding catalysis.

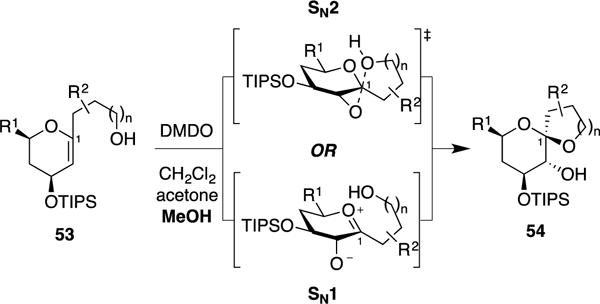

The observed stereoselectivity for inversion of configuration may be attributed to either SN2 or SN1 reaction manifolds (Figure 9). To distinguish between these two pathways, we carried out detailed kinetic studies of a series of electronically tuned glycal epoxide substrates (Figure 10a).26 Importantly, our systematic studies above on the synthesis of benzannulated spiroketals provided access to a series of C1-aryl glycal substrates 55a–f in which the electronic character of the anomeric carbon could be modulated using various aryl substituents.

Figure 9.

Possible SN2 and SN1 reaction mechanisms for the MeOH-induced kinetic spirocyclization of glycal epoxides leading to inversion of configuration at the anomeric carbon.

Figure 10.

Mechanistic studies of (a) MeOH-induced kinetic spirocyclization reactions and (b) acid-catalyzed spiroketal equilibration. 55–59a–f: X = OMe (a), Me (b), H (c), Cl (d), CF3 (e), NO2 (f).

In initial studies, these substrates were converted to the corresponding glycal epoxides 56a–f in situ and exposed to spontaneous thermal or MeOH-induced spirocyclization conditions (not shown). As expected, MeOH provided increased selectivity for inversion of configuration compared to the thermal cyclizations. Interestingly, for both thermal and MeOH reaction conditions, electron-donating substituents trended toward increased levels of retention products, while electron-withdrawing substituents instead favored inversion products. This reactivity trend is consistent with formation of retention products via an SN1 mechanism, in which a discrete oxocarbenium intermediate is stabilized by electron-donating substituents or destabilized by electron-withdrawing substituents. Conversely, these observations are also consistent with a proposed SN2 pathway for formation of the inversion products, as oxocarbenium formation should be strongly disfavored in substrates with electron-withdrawing C1-aryl substituents.

We next examined TsOH-catalyzed epimerization of contrathermodynamic inversion spiroketals 57a–f to the corresponding thermodynamic retention spiroketals 59a–f (Figure 10b). This epimerization reaction is known to proceed by an SN1 mechanism and the rate of conversion would serve as a benchmark against which to compare our proposed SN2 MeOH-catalyzed epoxide-opening spirocyclization. As expected, the electron-donating p-methoxy-substituted inversion spiroketal 57a (X = OMe) underwent rapid epimerization to retention spiroketal 59a within 2.5 min, while the electron-withdrawing p-nitro-substituted inversion spiroketal 57f (X = NO2) showed no conversion over 72 h. Intermediate rates were observed for spiroketals with substituents having intermediate electronic properties. Rate constants for these reactions were determined to define the Hammett correlation, giving a ρ value (slope) of –5.1, indicative of a distinctly positive SN1 transition state.

With a benchmark for SN1 reactions established, we examined reaction rates for MeOH-induced kinetic spirocyclizations of glycal epoxides 55a–f (Figure 10a). We anticipated that, if the spirocyclization reaction proceeds via an SN2 mechanism, the ρ value should be closer to zero than that observed for the TsOH epimerization, reflecting less buildup of positive charge at the reactive anomeric center. Thus, CD3OD-catalyzed spirocyclizations of glycals 55a–f were monitored by low temperature NMR, and initial rate constants were determined. The resulting Hammett correlation provided a ρ value of –1.3, indicative of an SN2 (or SN2-like) transition state.

We next carried out additional kinetic studies to evaluate the role of MeOH in catalysis. To determine the kinetic order of MeOH in the transition state, we measured the initial rates of spirocyclization of glycal epoxide 55c (R = H) in the presence of varying concentrations of CD3OD. Intriguingly, this analysis indicated that the spirocyclization reaction is second order in MeOH. In contrast, the corresponding intermolecular glycosylation reaction was found to be first order in MeOH. This provided a mechanistic explanation for the seemingly paradoxical finding earlier15 that increased MeOH concentration leads to increased spiroketal formation and decreased methyl glycoside formation.

Two additional experiments provided support for a role for hydrogen bonding in catalysis. Use of DMDO as an oxidant necessarily introduces acetone as a cosolvent in the spirocyclization reaction. Kinetic analysis revealed that acetone is a first-order inhibitor of the spirocyclization reaction, suggesting that it may compete as a hydrogen-bonding acceptor. Furthermore, spiroetherification of an analogous cyclohexene oxide substrate lacking the glycal ring oxygen (not shown) proceeded with fractional-order catalysis by MeOH (n = 0.59), suggesting that the ring oxygen in the corresponding glycal epoxides 55a–f may interact with MeOH in second-order catalysis of the spiroketal-forming reaction.

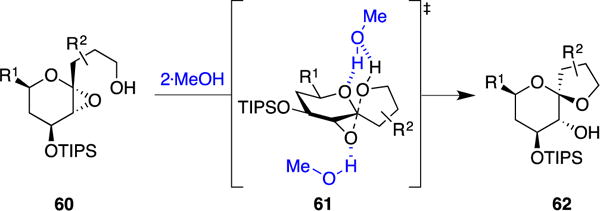

Taken together, these data support a proposed SN2 transition state 61 in which one equivalent of MeOH activates the epoxide oxygen as an electrophile, while a second equivalent of MeOH activates the side chain alcohol as a nucleophile (Figure 11). Hydrogen bonding of the second equivalent of MeOH to the ring oxygen may enhance reaction selectivity by disfavoring oxocarbenium formation in competing SN1 pathways (i.e.: forming retention spiroketals and methyl glycosides), while also directing the nucleophile to anti-attack to afford inversion of configuration at the anomeric carbon.

Figure 11.

Proposed hydrogen-bonding mechanism for MeOH-induced kinetic spirocyclization reaction.

In summary, detailed kinetic studies revealed a unique ability of MeOH to act as a hydrogen-bonding catalyst in epoxide-opening spirocyclization reactions, both controlling stereoselectivity and avoiding competing SN1-reaction pathways. Indeed, Jamison and coworkers have reported related catalytic functions of water in their epoxide-opening cascades to form ladder polyethers, with differential kinetic orders of hydrogen-bonding catalysis proposed to provide selectivity for competing endo and exo reaction manifolds.27 Taken together, these studies reveal the dramatic and specific roles that simple solvents can play in hydrogen-bonding catalysis of epoxide-opening reactions and raise the possibility that specific solvent catalysis may play as yet unappreciated roles in other reactions as well.

5. Solvent-dependent Sc(OTf)3-catalyzed Spirocyclization of exo-Glycal Epoxides to Form Benzannulated Spiroketals

In our original endo-glycal epoxide approach to benzannulated spiroketals, spirocyclization of side chains with phenol nucleophiles was particularly problematic, proceeding with low diastereoselectivity for inversion of configuration.25 To overcome this problem, we envisoned an alternative approach to benzannulated spiroketals in which the benzannulated ring system would be built into the substrate from the outset, with spirocyclization of a simple aliphatic side chain.

With this approach in mind, we devised a flexible synthetic route to access a variety of benzannulated exo-glycal epoxide (dihydrobenzofuran spiroepoxide) substrates 67 (Figure 12).28 From salicylaldehydes 63, alkyne additions afforded propargyl alcohols 64. Au(I)-mediated cycloisomerizations29 yielded exo-glycals 65. Protecting group manipulations were followed by diastereoselective anti-epoxidation with DMDO to provide exo-glycal epoxides 67.

Figure 12.

Synthesis of benzannulated spiroketals via solvent-dependent stereoselective spirocyclizations of exo-glycal epoxides.

We next focused on developing stereoselective spirocyclization reactions of exo-glycal epoxide 67 (R = H, n = 1). This epoxide was remarkably stable, even upon heating to 120 °C, in stark contrast to the corresponding endo-glycal epoxides, which cyclize spontaneously at –35 °C.26 In addition, the epoxide was unreactive under our MeOH- and Ti(Oi-Pr)4-induced spirocyclization conditions.15,24 After investigation of a wide range of Lewis acids, we discovered that treatment with Sc(OTf)3 favored the inversion spiroketal 68 (R = H, n = 1), which could be formed exclusively using a stoichiometric amount of catalyst in THF at – 20 °C. Other Lewis acids gave lower or even reversed diastereoselectivity. Low-temperature 1H-NMR experiments revealed that the Sc(OTf)3-catalyzed spirocyclization reaction proceeds under kinetic control between −35 and −20 °C, while higher temperatures lead to reduced diasteroselectivity. Interestingly, exposure of a diastereomeric mixture of spiroketals to Sc(OTf)3 in CH2Cl2 led to exclusive formation of the thermodynamically-favored retention spiroketal 69 (R = H, n = 1). Based on these results, it was apparent that Sc(OTf)3 plays divergent roles in the spirocyclization reaction depending on solvent selection (THF vs CH2Cl2).

We carried out mechanistic studies to investigate this striking phenomenon further. We noted that Sc(OTf)3 may act as either a Lewis acid or as a mild source of triflic acid.30 To differentiate between these two activities in the inversion reaction in THF, we added 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylpyridine (DTBMP) and found that dia-stereo-selectivity favoring the inversion spiroketal 68 was unaffected. Treatment with the Lewis acid ScCl3 also resulted in exclusive formation of the inversion spiroketal 68. Conversely, treatment with TfOH gave a diastereomeric mixture favoring the retention product 69. Thus, these studies suggest that Sc(OTf)3 acts as a Lewis acid in THF, effecting kinetic spirocyclization to form the contra-thermodynamic inversion spiroketal 68.

In parallel studies of the retention reaction in CH2Cl2, we found that addition of DTBMP led to a reversal of selectivity, forming a diastereomeric mixture favoring the inversion product 68. However, TfOH provided the retention spiroketal 69. Taken together, these studies suggest that Sc(OTf)3 acts as a mild source of Brønsted acid in CH2Cl2 to catalyze thermodynamically-controlled spirocyclization to retention spiroketal 69.

We next explored the scope of these stereocomplementary spirocyclization reactions. Spirocyclizations of substrates with longer side chains (n = 2–3) provided 6- and 7-membered ring spiroketals with complete diastereoselectivity under both solvent conditions. However, the 7-membered ring cyclization proceeded with lower yield due to an unexpected anti-Markovnikov 6-exo epoxide opening side reaction. Spirocyclizations of substrates with a variety of electron-withdrawing and -donating aryl substituents (R) also maintained high diastereoselectivities in all cases, demonstrating that the Sc(OTf)3-catalyzed reactions tolerate a wide range of functional groups. Consistent with electronic considerations, inclusion of a nitro group para to the phenol oxygen decreased reactivity at the anomeric spiroepoxide center, requiring heating to room temperature to induce spirocyclization in THF, while inclusion of a methoxy substituent at this position increased reactivity and decreased diastereoselectivity to 93:7 (68:69) in THF.

This new exo-glycal epoxide approach to benzannulated spiroketals highlighted the divergent catalytic activities of Sc(OTf)3 depending on solvent selection. In THF, the reaction proceeds via Lewis acid catalysis under kinetic control to provide contrathermodynamic inversion spiroketals. In contrast, in CH2Cl2, Brønsted acid catalysis under thermodynamic control produces retention spiroketals. While a structural rationale for the observed thermodynamic preference for retention spiroketals in this system requires further investigation, the reactions tolerate a wide range of functionalities and ring sizes. Importantly, this exo-glycal-based approach provides stereocontrolled access to contrathermodynamic phenolic spiroketals, which were difficult to obtain using our original endo-glycal-based approach.25 Applications of this method to the diversity-oriented synthesis of benzannulated spiroketal libraries are ongoing.

6. Synthesis of Pyrrolomorpholine Spiroketal Natural Products

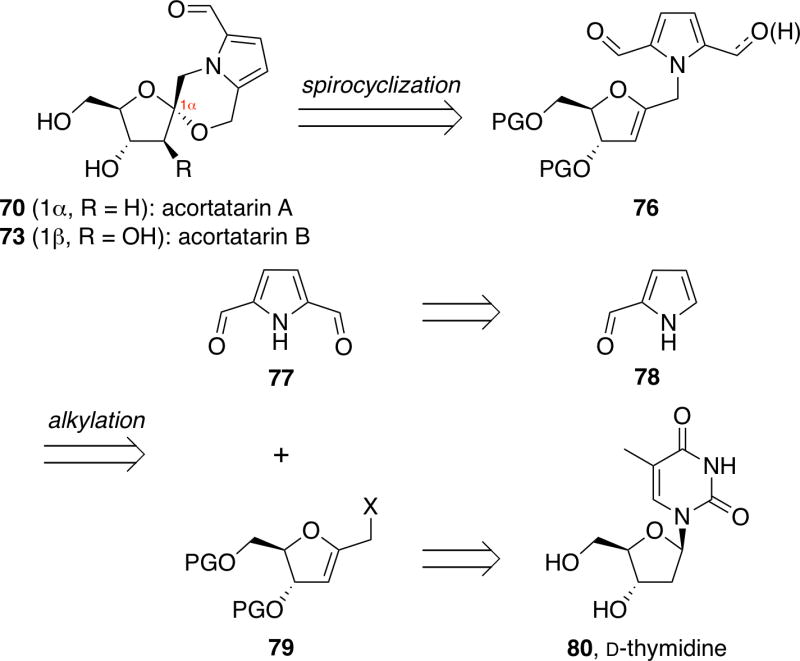

With an arsenal of methods for the stereocontrolled synthesis of spiroketals in hand, we sought to apply these approaches to the synthesis of pyrrolomorpholine spiroketal natural products. This novel family of naturally-occurring alkaloids includes both furanose and pyranose isomeric forms, as well as both epimeric α- and β-configurations at the anomeric carbon (Figure 13).31 These natural products were isolated from a variety of different plant species (Acorus tatarinowii, Brassica campestris, and Capparis spinosa, Shensong Yangxin capsules), as well as a fungus (Xylaria nigripes), all of which have been used in traditional Chinese medicines for the treatment of a variety of diseases. Notably, the acortatarins exhibit significant antioxidant activity against hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress in kidney cells,31a and similarly, the xylapyrrosides protect against peroxide-induced cytotoxicity in vascular smooth muscle cells.31f These antioxidant effects suggest that the pyrrolomorpholine spiroketals may have therapeutic potential for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy and other oxidative stress-related pathologies. However, due to the extremely limited quantities available from the natural sources, efficient synthetic access is needed for comprehensive biological studies. Accordingly, this family of natural products has attracted considerable attention from the synthetic community.31b,f,32 We envisioned that we might access the natural products and analogues efficiently using our glycal epoxide rubric and related glycal-based approaches.

Figure 13.

The pyrrolomorpholine spiroketal family of natural products.

Our initial efforts focused on the development of concise, highly stereoselective syntheses of the furanose natural products acortatarins A (70) and B (73).33 Retrosynthetically, we envisioned that both acortatarins A and B could be synthesized via spirocyclizations of a glycal intermediate 76 (Figure 14). This glycal precursor could be accessed in a modular fashion via coupling of pyrrole 77 with ribal 79, derived from commercially available D-thymidine (80).

Figure 14.

Retrosynthetic approach to acortatarins A and B.

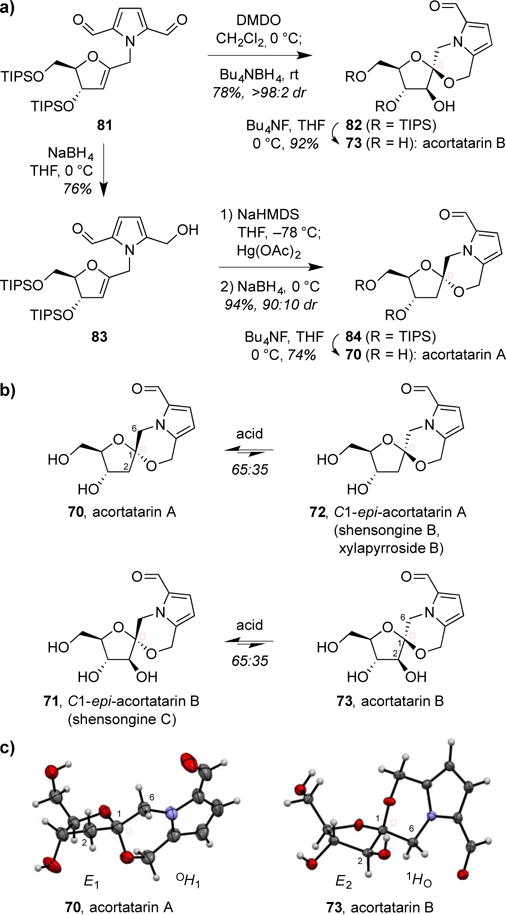

Thus, we synthesized the pyrrole-functionalized glycal substrate 81 (Figure 15a) in 6 steps and 58% yield from D-thymidine (not shown). In line with our glycal epoxide approach established above, we pursued an epoxidation–spirocyclization route to acortatarin B. After extensive optimization, we found that β-selective anti-epoxidation of diformylpyrrole-substituted glycal 81 with DMDO, followed by addition of Bu4NBH4 to effect in situ aldehyde reduction provided the desired β-spiroketal 82 with complete diastereoselectivity. The diformylpyrrole glycal 81 proved to be the ideal substrate for the reaction, as the electron-withdrawing aldehydes protected the pyrrole from undesired oxidation in the epoxidation step. Use of alternative reducing agents generally led to formation of other side products or decomposition. Interestingly, however, reductive spirocyclization with NaBH3CN under acidic conditions yielded the corresponding C1-epimeric α-spiroketal as a single diastereomer. Desilylation of β-spiroketal 82 provided acortatarin B (73) while C1-epi-acortatarin B (71, later isolated as the natural product shensongine C31e) was accessed by desilylation of the corresponding protected α-spiroketal (not shown).

Figure 15.

Stereoselective synthesis and thermodynamic preferences of acortatarins A and B. (a) Synthesis of acortatarin B via reductive epoxide-opening spirocyclization and of acortatarin A via Hg-mediated spirocyclization. (b) Acid equilibration favors the α-anomer in both systems. (c) Acortatarins A and B exhibit distinct ring conformations to enable double anomeric stabilization.

To synthesize acortatarin A, we pursued a mercury-mediated spirocyclization approach pioneered by Danishefsky and Pearson.34 In initial studies, we found that treatment of hydroxymethylpyrrole-functionalized glycal 83 with Hg(OAc)2, followed by NaBH4 reduction of the resulting 2-mercurial acetal, produced the desired α-spiroketal 84 with modest stereoselectivity (2:1 dr). Further studies revealed that pretreatment of glycal 83 with sodium hexamethyldisilazide improved diastereoselectivity for the α-spiroketal 84, presumably by forming a more reactive alkoxide nucleophile for cyclization. Use of weaker, non-nucleophilic bases provided lower diastereoselectivity. Moreover, allowing the initial oxymercuration reaction to proceed for longer times prior to NaBH4 reduction led to further increased diastereoselectivity to 9:1 dr favoring the α-spiroketal 84, suggestive of an equilibrium effect in this reaction. Desilylation of the 9:1 mixture of α- and β-spiroketals then provided separable acortatarin A (70) and C1-epi-acortatarin A (72, later isolated as the natural products shensongine B31e and xylapyrroside B31f) (Figure 13).

With the natural products and their C1 epimers in hand, we investigated their thermodynamic preferences via acid-catalyzed equlibration (Figure 15b). In both cases, the α-anomer was favored by a 65:35 ratio. Notably, this corresponds with the unnatural anomer of acortatarin B. To investigate the underlying structural bases for these thermodynamic preferences, we obtained an X-ray crystal structure of synthetic acortatarin B, and compared it to the previously reported crystal structure of acortatarin A31a (Figure 15c). This revealed that the two natural products adopt distinct conformations in both the furanose and morpholine rings, allowing double anomeric stabilization in both systems despite their opposite stereochemical configurations at the anomeric carbon.

In conclusion, the stereoselective synthesis of acortatarin A was achieved in 9 steps and 30% overall yield from D-thymidine with 9:1 dr in the key spirocyclization step, while acortatarin B was synthesized in 8 steps and 41% overall yield with complete diastereoselectivity in the key spirocyclization step. This compares favorably to previous syntheses and provides practical access to both the natural products and analogues for biological evaluation. Ongoing efforts are focused on expanding this approach to a family-level synthesis of the pyrrolomorpholine spiroketals and evaluating the biological activity and mechanisms of action of the natural products and analogues.

7. Conclusions

The stereocontrolled synthesis of spiroketals represents a classical challenge in organic synthesis and has presented fertile ground for both chemical and biological discoveries. In our own efforts to advance the glycal epoxide approach to spiroketals, we have developed new chemical methodologies of broad potential utility and fundamental insights into structure and reactivity. Efficient, systematic access to this chemotype now sets the stage for biological evaluation of spiroketals in the contexts of both diversity libraries and natural products and analogues.

Acknowledgments

We thank our coworkers Justin Potuzak, Sirkka Moilanen, Guodong Liu, Jacqueline Wurst, and Indrajeet Sharma for their scientific contributions described in this review. Generous financial support for this research program has been provided by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (P41 GM076267 to D.S.T., T32 CA062948-Gudas to A.L.V., P30 CA008748 to C. B. Thompson); PhRMA Foundation (to A.L.V.); Tri-Institutional PhD Program in Chemical Biology; Lucille Castori Center for Microbes, Inflammation and Cancer; NYSTAR Watson Investigator Program; Alfred P. Sloan Foundation; Tri-Institutional Stem Cell Initative; William H. Goodwin and Alice Goodwin and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research; Experimental Therapeutics Center of MSKCC; and William Randolph Hearst Fund in Experimental Therapeutics.

Biographies

Alyssa L. Verano received her BS in Chemistry from The College of New Jersey in 2010, where she discovered a burgeoning interest in the study of bioactive natural products, chemical biology, and drug discovery. She went on to pursue her PhD in Pharmacology at Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences and in 2011 joined the lab of Prof. Derek S. Tan at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to complete her thesis work on the synthesis and biological evaluation of spiroketal natural products.

Derek S. Tan received his BS in Chemistry from Stanford University in 1995, working with Prof. Dale G. Drueckhammer. He went onto graduate studies with Prof. Stuart L. Schreiber at Harvard University, receiving his PhD in Chemistry in 2000. He then joined the lab of Prof. Samuel J. Danishefsky at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) for his post-doctoral studies. He began his independent career at MSKCC in 2002 in the Molecular Pharmacology & Chemistry Program, with joint appointments at the Rockefeller University and Weill Cornell Medical College. He is currently a tenured Member and Tri-Institutional Professor. In 2015, he was appointed Chairman of the newly formed Chemical Biology Program at MSKCC. Since 2012, he has also been the Director of the Tri-Institutional PhD Program in Chemical Biology.

Footnotes

Dedicated to Professor Stuart L. Schreiber and Professor K. C. Nicolaou in honor of their receipt of the 2016 Wolf Prize in Chemistry

References

- 1 (a).Perron F, Albizati KF. Chem Rev. 1989;89:1617–1661. [Google Scholar]; (b) Aho JE, Pihko PM, Rissa TK. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4406–4440. doi: 10.1021/cr050559n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Francke W, Kitching W. Curr Org Chem. 2001;5:233–251. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sperry J, Wilson ZE, Rathwell DCK, Brimble MA. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:1117–1137. doi: 10.1039/b911514p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haniotakis G, Francke W, Mori K, Redlich H, Schurig V. J Chem Ecol. 1986;12:1559–1568. doi: 10.1007/BF01012372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hibbs RE, Gouaux E. Nature. 2011;474:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nature10139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4 (a).Lindvall MK, Pihko PM, Koskinen AMP. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23312–23316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kita A, Matsunaga S, Takai A, Kataiwa H, Wakimoto T, Fusetani N, Isobe M, Miki K. Structure. 2002;10:715–724. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizvi SA, Tereshko V, Kossiakoff AA, Kozmin SA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3882–3883. doi: 10.1021/ja058319c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seward EM, Carlson E, Harrison T, Haworth KE, Herbert R, Kelleher FJ, Kurtz MM, Moseley J, Owen SN, Owens AP, Sadowski SJ, Swain CJ, Williams BJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:2515–2518. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brasholz M, Soergel S, Azap C, Reissig HU. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:3801–3814. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deslongchamps P, Rowan DD, Pothier N, Sauve T, Saunders JK. Can J Chem. 1981;59:1105–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 9 (a).Palmes JA, Aponick A. Synthesis. 2012;44:3699–3721. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nagorny P, Sun Z, Winschel GA. Synlett. 2013;24:661–665. [Google Scholar]; (c) Quach R, Chorley DF, Brimble MA. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:7423–7432. doi: 10.1039/c4ob01325e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10 (a).Cremins PJ, Wallace TW. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1986:1602–1603. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cremins PJ, Hayes R, Wallace TW. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:3211–3220. [Google Scholar]

- 11 (a).Halcomb RL, Danishefsky SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:6661–6666. [Google Scholar]; (b) Baertschi SW, Raney KD, Stone MP, Harris TM. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:7929–7931. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friesen RW, Sturino CF. J Org Chem. 1990;55:5808–5810. [Google Scholar]

- 13 (a).Danishefsky S, Kitahara T. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:7807. [Google Scholar]; (b) Danishefsky S, Kerwin JF, Jr, Kobayashi S. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:358–360. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joly GD, Jacobsen EN. Org Lett. 2002;4:1795–1798. doi: 10.1021/ol0258785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potuzak JS, Moilanen SB, Tan DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13796–13797. doi: 10.1021/ja055033z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiBlasi CM, Macks DE, Tan DS. Org Lett. 2005;7:1777–1780. doi: 10.1021/ol050370y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varelis P, Graham AJ, Johnson BL, Skelton BW, White AH. Aust J Chem. 1994;47:1735–1739. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moilanen SB, Tan DS. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:798–803. doi: 10.1039/b417429a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinnaird JWA, Ng PY, Kubota K, Wang X, Leighton JL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7920–7921. doi: 10.1021/ja0264908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald FE, Reddy KS, Diaz Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4304–4309. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potuzak JS, Tan DS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:1797–1801. [Google Scholar]

- 22 (a).Paterson I, Wallace DJ, Gibson KR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:8911–8914. [Google Scholar]; (b) Holson EB, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2002;4:3719–3722. doi: 10.1021/ol0266875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Takaoka LR, Buckmelter AJ, LaCruz TE, Rychnovsky SD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:528–529. doi: 10.1021/ja044642o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23 (a).Barresi F, Hindsgaul O. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9376–9377. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stork G, Kim G. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1087–1088. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ito Y, Ogawa T. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1994;33:1765–1767. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moilanen SB, Potuzak JS, Tan DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1792–1793. doi: 10.1021/ja057908f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu G, Wurst JM, Tan DS. Org Lett. 2009;11:3670–3673. doi: 10.1021/ol901437f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wurst JM, Liu G, Tan DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7916–7925. doi: 10.1021/ja201249c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27 (a).Vilotijevic I, Jamison TF. Science. 2007;317:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1146421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Byers JA, Jamison TF. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6383–6385. doi: 10.1021/ja9004909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Morten CJ, Jamison TF. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6678–6679. doi: 10.1021/ja9025243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Morten CJ, Byers JA, Jamison TF. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1902–1908. doi: 10.1021/ja1088748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Byers JA, Jamison TF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16724–16729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311133110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma I, Wurst JM, Tan DS. Org Lett. 2014;16:2474–2477. doi: 10.1021/ol500853q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harkat H, Blanc A, Weibel JM, Pale P. J Org Chem. 2008;73:1620–1623. doi: 10.1021/jo702197b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30 (a).Wabnitz TC, Yu JQ, Spencer JB. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:484–493. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rosenfeld DC, Shekhar S, Takemiya A, Utsunomiya M, Hartwig JF. Org Lett. 2006;8:4179–4182. doi: 10.1021/ol061174+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dang TT, Boeck F, Hintermann L. J Org Chem. 2011;76:9353–9361. doi: 10.1021/jo201631x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acortatarins; (a) Tong XG, Zhou LL, Wang YH, Xia C, Wang Y, Liang M, Hou FF, Cheng YX. Org Lett. 2010;12:1844–1847. doi: 10.1021/ol100451p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiang D, Peterson DG. Food Chem. 2013;141:1345–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pollenopyrrosides:; (c) Guo JL, Feng ZM, Yang YJ, Zhang ZW, Zhang PC. Chem Pharm Bull. 2010;58:983–985. doi: 10.1248/cpb.58.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Capparisines:; (d) Yang T, Wang C-h, Chou G-x, Wu T, Cheng X-m, Wang Z-t. Food Chem. 2010;123:705–710. [Google Scholar]; Shensongines:; (e) Ding B, Dai Y, Hou YL, Yao XS. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2015;17:559–566. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2015.1047354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Xylapyrrosides:; (f) Li M, Xiong J, Huang Y, Wang LJ, Tang Y, Yang GX, Liu XH, Wei BG, Fan H, Zhao Y, Zhai WZ, Hu JF. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:5285–5295. [Google Scholar]

- 32 (a).Sudhakar G, Kadam VD, Bayya S, Pranitha G, Jagadeesh B. Org Lett. 2011;13:5452–5455. doi: 10.1021/ol202121k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Geng HM, Chen JLY, Furkert DP, Jiang S, Brimble MA. Synlett. 2012;23:855–858. [Google Scholar]; (c) Borrero NV, Aponick A. J Org Chem. 2012;77:8410–8416. doi: 10.1021/jo301835e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Teranishi T, Kageyama M, Kuwahara S. Biosci, Biotechnol, Biochem. 2013;77:676–678. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Cao Z, Li Y, Wang S, Guo X, Wang L, Zhao W. Synlett. 2015;26:921–926. [Google Scholar]; (f) Cao P, Li ZJ, Sun WW, Malhotra S, Ma YL, Wu B, Parmar VS. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2015;5:37–45. doi: 10.1007/s13659-014-0049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Wood JM, Furkert DP, Brimble MA. Org Biomol Chem. 2016;14:7659–7664. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01361a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wurst JM, Verano AL, Tan DS. Org Lett. 2012;14:4442–4445. doi: 10.1021/ol3019456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Danishefsky SJ, Pearson WH. J Org Chem. 1983;48:3865–3866. [Google Scholar]