Abstract

In this work, we describe the SuFEx-based polycondensation between bisalkylsulfonyl fluorides (AA monomers) and bisphenol bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ethers (BB monomers) using [Ph3P=N-PPh3]+[HF2]− as the catalyst. The AA monomers were prepared via the highly reliable Michael addition of ethenesulfonyl fluoride and amines/anilines while the BB monomers were obtained from silylation of bisphenols by t-butyldimethylsilyl chloride. With these reactions, we were able to achieve a remarkable diversity of monomeric building blocks by exploiting readily available amines, anilines, and bisphenols as starting materials. The SuFEx-based polysulfonate formation reaction exhibited excellent efficiency and functional group tolerance, producing polysulfonates with a variety of side chain functionalities in >99% conversion within 10 min to 1 h. When bearing an orthogonal group on the side chain, the polysulfonates can be further functionalized via click-chemistry based post-polymerization modification.

Keywords: polysulfonate formation, ethenesulfonyl fluoride, SuFEx reaction, bifluoride salt, click chemistry

Graphical abstract

The sulfur(VI) fluoride exchange (SuFEx)-based polycondensation reaction between bisalkylsulfonyl fluorides and bisphenol bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ethers using [Ph3P=N-PPh3]+[HF2]− as the catalyst was developed. Polysulfonates synthesized via this method can be further functionalized using click chemistry based transformations orthogonal to SuFEx.

Polycondensation reactions, in which the side-chain functionality is not compromised by main-chain formation, are compelling for synthesizing polymers with desired repeating units.[1] Ideally, the side chain groups remain to be further derivatized to gain versatility, complexity, and desired functions.[2] Such polymerization reactions usually require a high degree of functional group compatibility, which is a grand challenge in the field of polymer synthesis.[3] The development of click chemistry provides a timely solution to these obstacles.[4]

Click chemistry encompasses any reaction that proceeds with exquisite selectivity, quantitative yield, and near-perfect fidelity in the presence of a wide variety of functional groups.[3] The discovery of the Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction in 2002[5] has provided a versatile and highly efficient method to fabricate functionalized materials with absolute fidelity, high levels of control, and excellent functional group compatibility.[6] Several breakthroughs in polymer fabrication have been made possible using this methodology.[7] For example, CuAAC enables the facile coupling of two distinct linear polymers to form block copolymers, a notorious synthetic challenge due to the reduced reactivity between polymeric chain ends.[8] This reaction also provides a straightforward solution for the construction of templated star polymers and brush-block co-polymers.[9]

In 2014, we reported a new family of click reactions, which we termed “sulfur(VI) fluoride exchange” (SuFEx),[10] to create molecular connections with absolute reliability and unprecedented efficiency through a sulfur(VI) hub. Unlike the S(VI)-Cl bond, which is exceedingly sensitive to reductive environments and yields S(IV) species in such conditions, the S(VI)-F bond allows only the substitution pathway to occur, and therefore it possesses an ideal combination of synthetic accessibility and stability.[10] Since then, SuFEx has been successfully applied to surface modification, polymer synthesis, and post-polymerization modification.[11] We discovered that 1,8-diazabicycloundec-7-ene (DBU) and 2-tert-butylimino-2-diethylamino-1,3-dimethylperhydro-1,3,2-diazaphosphorine (BEMP) could initiate the SuFEx-based polycondensation reaction of bisphenol A bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ethers and bisphenol A bis(fluorosulfate) to form polysulfates with high number-average molecular weight (Mn), narrow polydispersity, and near quantitative yields. Compared to bisphenol A-derived polycarbonate, which is a widely used thermoplastic polymer, the bisphenol A-based polysulfates exhibit better thermal and hydrolytic stability, implicating potential applications under harsh environments.

In our exploration of SuFEx-based polycondensation processes, the structurally related polysulfonates (-SO2O-) attracted our attention.[12] This family of polymers shows considerable potential as moldable high-impact engineering thermoplastics and as useful materials for making films, fibers and coatings. However, most established attempts to synthesize polysulfonates relied on reacting sulfonyl chlorides with phenols under basic condition.[12-13] The poor selectivity of sulfonyl chlorides in this process significantly limits the utility of these methods, and as a consequence, the structures of currently available polysulfonates are quite limited. [10, 11c]

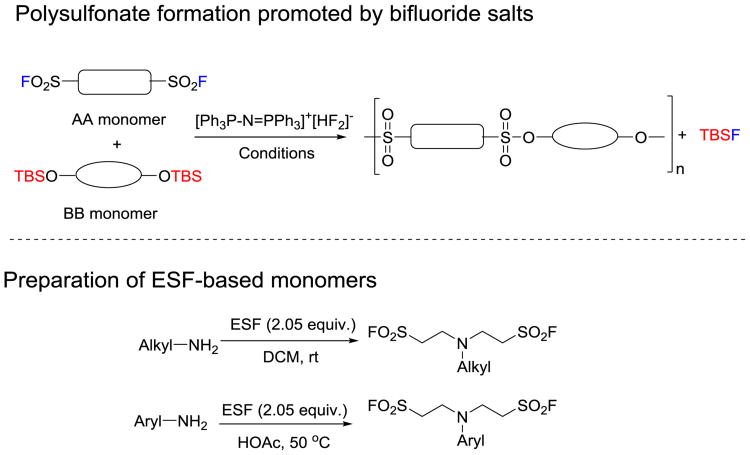

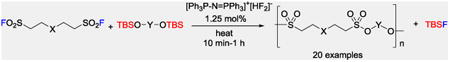

Here, we report on the finding that the bifluoride salt [Ph3P=N-PPh3]+[HF2]− is an excellent catalyst for the synthesis of polysulfonate polymers via a AA-BB polycondensation process (Figure 1). As low as 1.25 mol% catalyst loading is sufficient to produce polysulfonates in 99% conversion in an hour or less. Moreover, we are able to achieve great diversity in the polymeric backbone by harnessing the power of the ethenesulfonyl fluoride (ESF)-based Michael addition reaction for monomer synthesis.[10, 14] Finally, we demonstrate that polysulfonates formed by this process can be further functionalized by exploiting click-chemistry transformations that are orthogonal to SuFEx.

Figure 1.

Bifluoride promoted polysulfonate formation between bisalkylsulfonyl fluorides and bisphenol bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ethers.

Since its introduction in 1953, ESF has been noted as a dienophile, a 1,3-dipolarphile, and a good Michael acceptor. [14-15] In fact, the reactions of ESF with a variety of nucleophiles are excellent approaches to produce alkyl sulfonyl fluorides.[10, 14, 15h] To produce polysulfonates with excellent repeating units variability, we chose ESF-amine/aniline adducts (i.e., bis-functionalized alkylsulfonyl fluorides) as AA monomers to react with bisphenol bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ethers (BB monomers) based on the following considerations: (1) amines, anilines and bisphenols are readily availability from commercial sources; (2) bis-functionalized and multi-functionalized amines and anilines have been wide applied in polymer science.[16]

To construct ESF-based AA monomers, we mixed one equivalent of aliphatic amines with 2.05 equivalents of ESF in CH2Cl2 at room temperature for 2 h to 6 h to give the desired bisalkylsulfonyl fluorides in good to excellent yields without or with only minor purification. In parallel, the aniline-ESF adducts were prepared using acetic acid as the solvent. Reaction at 50 °C overnight afforded the corresponding products in near quantitative yields (Figure 1). It should be noted that by using our recently developed interphase, kilogram-scale ESF synthesis technique,[15f] amine/aniline ESF adducts (i.e., AA monomers) can be reliably prepared in hundred-gram scale quantities. On the other hand, the synthesis of bisphenol bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ethers (BB monomers) is accomplished by reacting t-butyldimethylsilyl chloride with bisphenols.[11c].

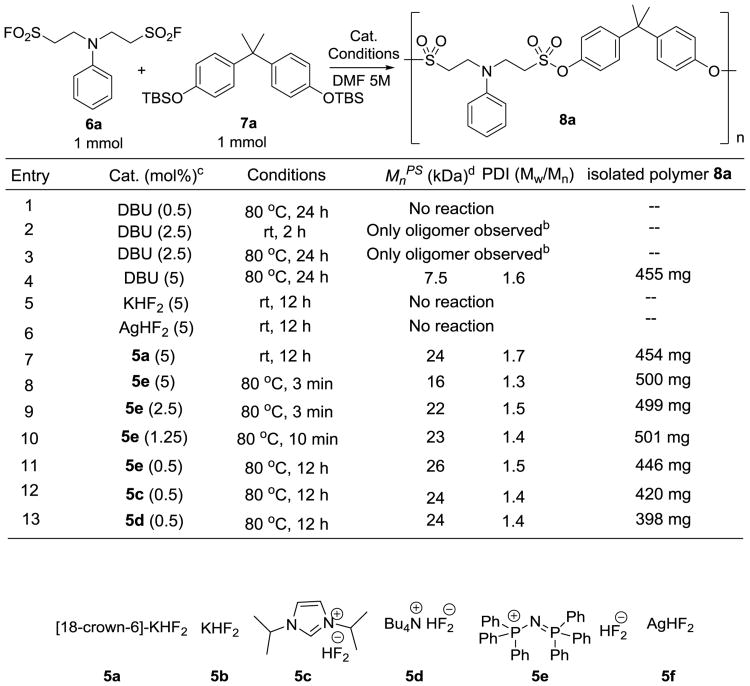

With bisalkylsulfonyl fluorides and bisphenol bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ethers in hand, we next explored the SuFEx-based polycondensation reaction of these monomers. Exploiting the established catalyst (DBU) developed in the formation of bisphenol A polysulfates, our initial attempt between bis(alkylsulfonyl fluoride) 6a and bisphenol A bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ether 7a in dimethylformamide (DMF) was disappointing (Figure 2, entry 1-3).[11c, 17] In the presence of DBU (5 mol%), we obtained polysulfonate 8a with a relatively low molecular weight (Mnps = 7.5 kDa) (Figure 2, entry 4). Bis(alkylsulfonyl fluoride) 6a possesses an acidic proton at the α position of the sulfonyl fluoride moiety. Chances are that dehydrofluorination takes place under basic condition to yield highly reactive sulfene-type intermediates that may react with trace amounts of impurities, e.g. water or dimethyl amine in the polymerization solvent (DMF), thus terminate the chain growth.[18]

Figure 2.

Polysulfonate 8a formation under different catalytic conditions. a) Workup conditions: After the reaction went to completion, the solution was diluted with same volume of DMF followed by precipitation from methanol). b) No solid precipitation was observed after workup c) Catalyst loading was calculated based on the functional groups. d) Mnps values were Mn in reference to polystyrene standards.

We recently discovered that bifluoride salts serve as excellent catalysts to promote SuFEx-based polymerization between bisphenol A bisfluorosulfate and the bisphenol A bis(t-butyldimethyl silyl) ether.[19] Compared to DBU, bifluoride salts are superior catalysts in terms of catalyst loading, stability,[20] functional group compatibility, as well as cost effectiveness. Most importantly, bifluoride salts are either neutral or slightly acidic[21] and are therefore well-suited for activation of base-sensitive alkylsulfonyl fluorides.

Encouraged by these discoveries, we assessed the possibility of using bifluoride salts to catalyze the polycondensation of bis(alkylsulfonyl fluoride) 6a and bisphenol A bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ether 7a (Figure 2, entry 5-13). To evaluate the effects of counter ions, six different bifluoride salts, including [18-crown-6]-KHF2 (5a), KHF2 (5b), N,N′-diisopropylimdazonium bifluoride (5c), tetrabutylammonium bifluoride (5d), [Ph3P=N-PPh3]+[HF2]− (5e), and AgHF2 (5f), were selected as catalytic species. As shown in Figure 2, counter ions were found to have a profound impact on the catalytic activity of the corresponding bifluoride salts. Neither KHF2 nor AgHF2 was able to initiate polysulfonate formation. This might be due to the “tightness” of the ion pairs in the reaction mixture. With the addition of a cationic chelating agent, [18-crown-6], to KHF2 (1/1, 0.1 M in acetonitrile, 5 mol%), we were able to promote polymerization at room temperature, producing polysulfonate 8a (Mnps = 24 kDa, PDI = 1.7) within 12 h (Figure 2, entry 7). By contrast, the organic-ammonium and phosphonium bifluoride salts exhibited excellent catalytic activity. In the presence of only 0.5 mol% of 5e, the polycondensation reaction was accomplished in 12 h at 80 °C in dimethylformamide (5 M solution of monomers in DMF) (condition A) (Figure 2, entry 11). Interestingly, this polycondensation was dramatically accelerated with higher catalyst loading (5e, 1.25% mol), producing polysulfonate 8a (Mn = 22 kDa) in 99% conversion within 10 min (Figure 2, entry 10) (condition B). We next carefully monitored the consumption of the sulfonyl fluoride moiety under both conditions described above using 1H-NMR (SI, Figure S1). Under condition B, the sulfonyl fluoride was consumed much faster; reaching full conversion in only 1 min. By contrast, the consumption of the sulfonyl fluoride moiety under condition A was quite slow, requiring 12 h to complete. Other bifluoride salts, including 5c and 5d, also exhibited similar catalytic capability; albeit the weights of the isolated polymer were slightly lower (entry 12, 13).

Notably, we found that bifluoride salt 5e catalyzed process does not require absolutely anhydrous conditions. However, the addition of 5 vol% water as the co-solvent completely suppressed the polymer formation. This phenomenon was also observed when 5 vol% of water was added as the co-solvent to the 5e (1.25 mol%) catalyzed SuFEx reaction between alkylsulfonyl fluoride 4 and 4-methylphenol t-butyldimethylsilyl ether 3 (SI, Figure S2). This is not surprising because large amount of water will hydrolyze the reactive intermediates and thereby terminate the polymerization. In addition, benzoic acid (1 equivalent) also prevented the coupling reaction from taking place, leading to the full recovery of the starting materials. When deuterated 4-Me-phenol was employed as an additive (one equivalent), crossover products were detected by 1H-NMR (SI, Figure S3), indicating an intermolecular proton transfer between the phenol additive and the bifluoride-activated silyl ether.

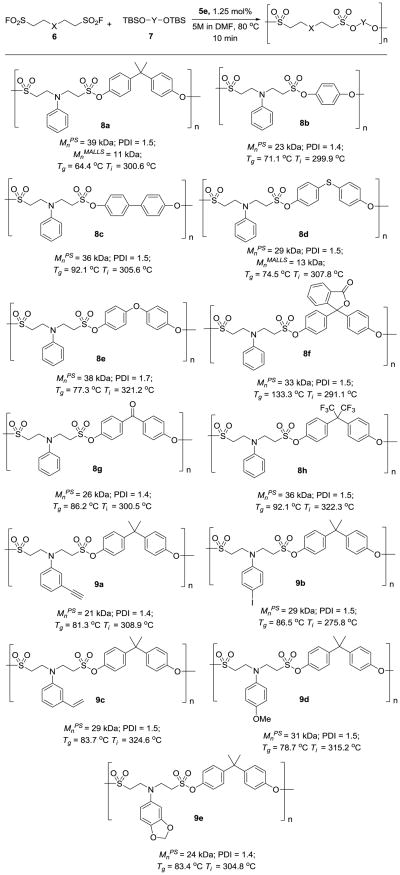

After the identification of the optimal polycondensation condition (condition B), we then investigated the substrate scope of this polysulfonate formation process. As shown in Figure 3, when we used 6a as the coupling partner, bifluoride salt 5e catalyzed polycondensation was applicable to various substrates, including 1,4-dihydroxylbenzene bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ether (7b), 4,4′-biphenol bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ether (7c), 4,4′-thiodiphenol bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ether (7d), 4,4′-dihydroxyldiphenyl ether bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ether (7e), phenolphthalein bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ether (7f), and 4,4′-dihydroxybenzophenone bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ether (7g), affording polysulfonates 8a-h within 10 min. Other aniline-ESF adducts with functional groups on the phenyl ring (6b-f, SI section B, C), which can be exploited for post-polymerization modification, also reacted smoothly with compound 7a in the presence of 1.25 mol% 5e, generating polysulfonates 9a-e (Figure 3) in greater than 99% conversion (SI, Figure S5). The Mnps of these polysulfonates are between 21 kDa to 39 kDa with PDIs ranging from 1.4 to 1.7. The absolute number average molecular weight of polysulfonate 8a and 8d, as determined by multi-angle laser light scattering (MALLS), is 11 kDa and 13 kDa, respectively.

Figure 3.

Preparation of polysulfonate polymers from aniline ESF adducts 6 and bisphenol A bis(t-butyldimethylsilyl) ether 7a. a) The reactions were conducted with 0.5 mmol of each monomer for 10 min. b) The catalyst loading was calculated based on the functional groups. c) The products were isolated by precipitation from methanol and analyzed by Gel permeation chromatography (GPC). d) Mnps values were Mn in reference to polystyrene standards. e) MnMALLS values were determined by multi-angle laser light scattering. f) Ti = 5% weight loss temperature.

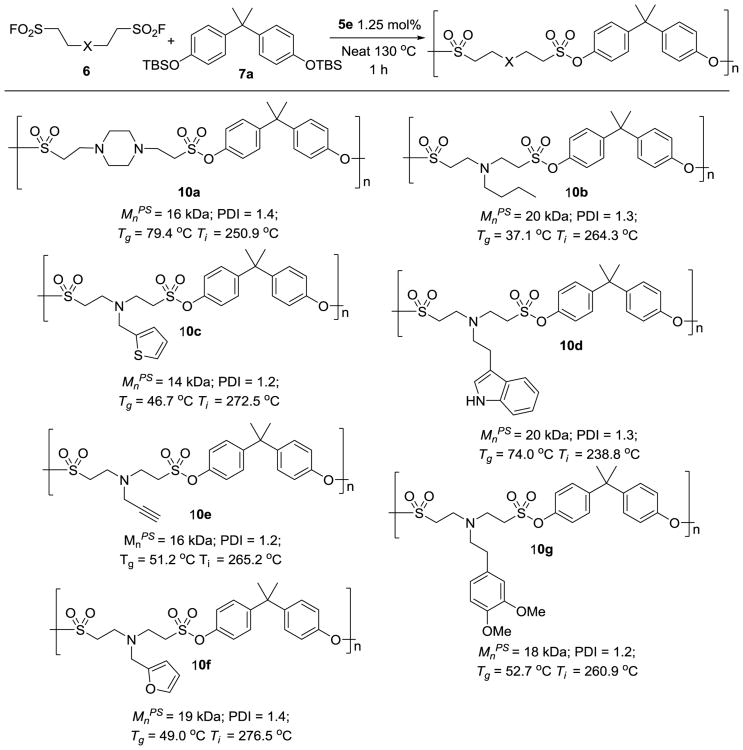

Sulfonyl fluorides containing tertiary aliphatic amines that had been derivatized from the Michael addition of aliphatic amines and ESF were also found to be excellent AA monomers for SuFEx-based polymerization (Figure 4). This polycondensation reaction takes a longer time and requires higher temperature. We suspect that the protonated tertiary amine in bissulfonyl fluorides may interact with the bifluoride ion, which restricts its free movement, and thus slows down the SuFEx reaction. Nevertheless, the reaction of aliphatic amine-ESF adducts 6g-n (SI, section B) and 7a was performed as a neat mixture under elevated temperature (130 °C) in the presence of 1.25 mol% 5e for 1 h, and the corresponding polysulfonates were produced with 99% conversion of the sulfonyl fluoride moiety (SI, Figure S5) (Mn from 14 kDa to 20 kDa). The PDIs of the resulting polysulfonates range from 1.2 to 1.4.

Figure 4.

Preparation of polysulfonates from amine ESF adducts. a) The reactions were conducted with 0.5 mmol of each monomer. The catalyst loading was calculated based on the functional groups. The products were isolated by precipitation from methanol and analysed by GPC. Mnps values were in reference to polystyrene standards. b) Ti = 5% weight loss temperature.

We next performed the physical property characterizations of the polysulfonates listed in Figure 3 and 4, including glass-transition temperature (Tg) and thermal gravimetric analysis. Depending on the structures of the monomers, Tgs of the corresponding polysulfonates varied significantly (Figure 3-4). For example, the Tg of polysulfonate 10b is 37 °C, while the Tg of polysulfonate 8f is 133 °C.[22] Thermal gravimetric analysis indicated that procedural decomposition temperatures (Ti) of the polysulfonates are excellent with 5% weight loss occurring from 238 °C to 321 °C.

We discovered that the molecular weight of the polysulfonates formed by this process can be easily controlled by employing non-stoichiometric monomers—the molecular weight decreases along with increasing loading of one monomer. For example, in the preparation of polysulfonate 8a, by increasing the loading of monomer 6a from 1 to 1.05 eq, the Mnps of the resulting polysulfonate 8a decreased from 33 kDa to 26 kDa. When 1.1 equivalent of 6a was employed, the Mnps of the resulting polysulfonate decreased further to 19 kDa (SI, Figure S6).

19F-NMR and MALDI-TOF analysis revealed that polysulfonate 8a possesses linear structure with sulfonyl fluoride as the ending group on both chain ends when excess of 6a was employed and with phenol as the ending group when excess of 7a was employed. Under the stoichiometric reaction condition, the linear polysulfonate contains sulfonyl fluoride on one end and a phenol group on the other (SI, Figure S7 and S8).

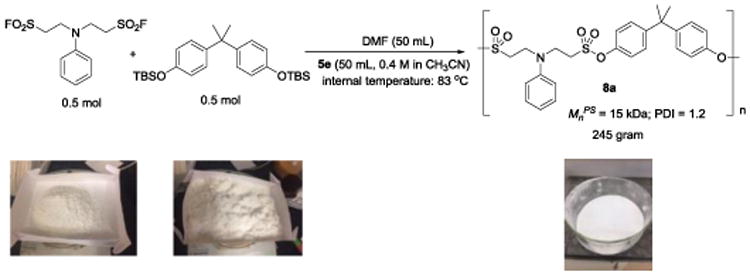

To evaluate the feasibility of large scale polysulfonate synthesis, we scaled up the polycondensation of 6a and 7a to 0.5 mol (Figure 5; SI, Figure S9). The reaction was performed in DMF (50 mL) at 83 °C (internal temperature). Catalyst 5e (50 mL, 0.4 M solution in acetonitrile, 1.00 mol%) was added dropwise. We observed a rapid temperature increase with the addition of the catalyst (from 83 °C to 102 °C), which indicating this polymerization reaction is exothermic. Next, the byproduct t-butyldimethylsilylfluoride and acetonitrile were distilled off, and the residue was diluted with DMF and slowly poured into methanol with vigorous stirring followed by filtration to afford 245 grams of polysulfonate 8a (Mnps = 15 kDa) as a white solid.

Figure 5.

Large scale synthesis of polysulfonate 8a.

The stability of polysulfonate 8a generated from the large scale synthesis was then evaluated in the presence of sodium carbonate (1 M, 1:2 EtOH/H2O), sodium hydroxide (1 M, 1:2 EtOH/H2O), or hydrochloric acid (1 M, 1:2 EtOH/H2O) at 80 °C, respectively. Polysulfonate 8a exhibited good hydrolytic stability under both acidic and basic conditions as no significant changes in molecular weight were observed within 8 h (SI, Figure S10).

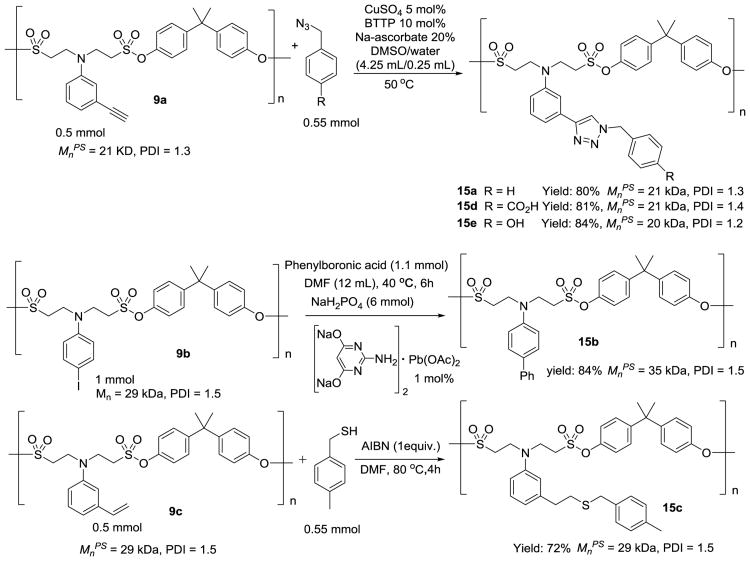

The orthogonal nature of SuFEx to other types of click reactions enables the incorporation of a diverse array of clickable groups onto the side chains of polysulfonates for post-polymerization modification, which is a facile means to endow parent polymers with new properties.[23] As shown in Figure 6, polysulfonate 9b features a 4-iodophenyl pendant that can be modified via the Suzuki coupling reaction [24] to form polysulfonate 15b in 84% isolated yield. Likewise, reacting polysulfonate 9c with benzyl thiol via the thiol-ene click reaction[25] afforded the corresponding polysulfonate 15c in 72% isolated yield. In our hands, the ligand-accelerated CuAAC serves as the most efficient approach for post-polymerization modification. Reacting the alkyne containing polysulfonate 9a with benzyl azide in the presence of CuSO4 (5 mol%), BTTP (10 mol%),[26] and sodium ascorbate (20 mol%) in DMSO-water (95:5) mixture provided polymer 15a in 80% isolated yield.[27] Significantly, CuAAC is also able to introduce functional groups into polysulfonates (e.g., acids and phenols) that are otherwise not compatible with the SuFEx-based coupling of sulfonyl fluorides and bisphenol silyl ethers. As shown in Figure 6, 4-azidomethylbenzoic acid and 4-azidomethylphenol were successfully reacted with the alkyne-functionalized polysulfonate 9a to generate the corresponding 1,2,3-triazole linked derivatives 15d and 15e in excellent yields.

Figure 6.

Post-polymerization modification of polysulfonate 9a, 9b, and 9c.

In summary, we have developed a [Ph3P=N-PPh3]+[HF2]−catalyzed AA-BB polycondensation reaction to generate polysulfonates with diverse structures and narrow polydispersity. This process is highly reliable and efficient, requiring only 1.25 mol% catalyst loading. The resulting polysulfonates exhibit excellent thermal and hydrolytic stability. In this process, diversity in the polymeric backbones is introduced by choosing a diverse array of monomers synthesized by the Michael addition of readily available amines or anilines to ESF and the silylation of various bisphenols. Due to the orthogonal nature of SuFEx to other click-type transformations, clickable functional groups can be incorporated into the side-chains of the resulting polysulfonates to further increase the versatility of the parent polymers. Featuring excellent fidelity, high efficiency, substrate diversity, functional group tolerance, as well as post-polymerization modification compatibility, the process reported herein offers a fast and reliable methodology to fabricate polysulfonates with a variety of side chain functionalities. We expect this polymerization process to have immediate applications to functional macromolecule fabrication. Step growth processes are governed by Carothers kinetics, which describes that polydispersity of polymers formed by polycondensation should approaching 2 with near quantitative conversion. Given that the conversions in this process are greater than 99% and the polydispersity of resulting polysulfonates range from 1.2 to 1.7, we suspect that this polymerization reaction does not follow a conventional step growth mechanism. The mechanistic investigation of this polymerization is currently undergoing in our laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the National Science Foundation (CHE 1610987 to K.B.S.) and the National Institutes of Health (R01GM113046 to P.W.). Part of the work was carried out as a user project at the Molecular Foundry, which was supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. We thank Dr. Larissa Krasnova for her initial work on this project using DBU as the catalyst.

Contributor Information

Hua Wang, Department of Chemical Physiology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States; Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States.

Feng Zhou, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States; College of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou, Nano Science and Technology, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, P. R. China.

Gerui Ren, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States; Department of Applied Chemistry, School of Food Science and Biotechnology, Zhejiang Gongshang University, Hangzhou 310018, P. R. China.

Qinheng Zheng, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States.

Hongli Chen, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States.

Bing Gao, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States.

Liana Klivansky, The Molecular Foundry, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720, United States.

Yi Liu, The Molecular Foundry, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720, United States.

Bin Wu, College of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou, Nano Science and Technology, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, P. R. China.

Qingfeng Xu, College of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou, Nano Science and Technology, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, P. R. China.

Jianmei Lu, College of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou, Nano Science and Technology, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, P. R. China.

K. Barry Sharpless, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States.

Peng Wu, Department of Chemical Physiology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States.

References

- 1.Ober CK, Cheng SZD, Hammond PT, Muthukumar M, Reichmanis E, Wooley KL, Lodge TP. Macromolecules. 2009;42:465–471. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Gunay KA, Theato P, Klok HA. J Polym Sci Pol Chem. 2013;51:1–28. [Google Scholar]; b) Romulus J, Henssler JT, Weck M. Macromolecules. 2014;47:5437–5449. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawker CJ, Wooley KL. Science. 2005;309:1200–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1109778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tornoe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lutz JF. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:1018–1025. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Meldal M. Macromol Rapid Comm. 2008;29:1016–1051. [Google Scholar]; b) Lawrence J, Lee SH, Abdilla A, Nothling MD, Ren JM, Knight AS, Fleischmann C, Li Y, Abrams AS, Schmidt BVKJ, Hawker MC, Connal LA, McGrath AJ, Clark PG, Gutekunst WR, Hawker CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:6306–6310. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Amir F, Jia ZF, Monteiro MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:16600–16603. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Barnes JC, Ehrlich DJC, Gao AX, Leibfarth FA, Jiang Y, Zhou E, Jamison TF, Johnson JA. Nat Chem. 2015;7:810–815. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Opsteen JA, van Hest JCM. Chem Commun. 2005:57–59. doi: 10.1039/b412930j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) van Dongen SFM, Nallani M, Schoffelen S, Cornelissen JJLM, Nolte RJM, van Hest JCM. Macromol Rapid Comm. 2008;29:321–325. [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Sumerlin BS, Tsarevsky NV, Louche G, Lee RY, Matyjaszewski K. Macromolecules. 2005;38:7540–7545. [Google Scholar]; b) Binder WH, Kluger C. Macromolecules. 2004;37:9321–9330. [Google Scholar]; c) Neumann S, Dohler D, Strohl D, Binder WH. Polym Chem. 2016;7:2342–2351. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong JJ, Krasnova L, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2014;53:9430–9448. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Yatvin J, Brooks K, Locklin J. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2015;54:13370–13373. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brooks K, Yatvin J, McNitt CD, Reese RA, Jung C, Popik VV, Locklin J. Langmuir. 2016;32:6600–6605. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b01591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Dong JJ, Sharpless KB, Kwisnek L, Oakdale JS, Fokin VV. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2014;53:9466–9470. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yatvin J, Brooks K, Locklin J. Chem-Eur J. 2016:16348–16354. doi: 10.1002/chem.201602926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Li SH, Beringer LT, Chen SY, Averick S. Polymer. 2015;78:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Work JL, Herweh JE. J Polym Sci A1. 1968;6:2022–2030. [Google Scholar]; b) Forrette JE, Burroughs JE, Booker CC. J Appl Polym Sci. 1968;12:2039–2045. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vizgert RV, Budenkova NM, Maksimenko NN. Polym Sci U S S R. 1989;31:1508–1511. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krutak JJ, Burpitt RD, Moore WH, Hyatt JA. J Org Chem. 1979;44:3847–3858. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Qin HL, Zheng QH, Bare GAL, Wu P, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2016;55:14155–14158. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hedrick RM United States Patent 2,653,973. 1953 [Google Scholar]; c) Hyatt JA, White AW. Synthesis-Stuttgart. 1984:214–217. [Google Scholar]; d) Chanetray J, Vessiere R, Zeroual A. Heterocycles. 1987;26:101–108. [Google Scholar]; e) Mykhailiuk PK. Chem-Eur J. 2014;20:4942–4947. doi: 10.1002/chem.201304840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Zheng Q, Dong J, Sharpless KB. J Org Chem. 2016;81:11360–11362. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Zelli R, Tommasone S, Dumy P, Marra A, Dondoni A. Eur J Org Chem. 2016:5102–5116. [Google Scholar]; h) Chen Q, Mayer P, Mayr H. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2016;55:12664–12667. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Bogolubsky AV, Moroz YS, Mykhailiuk PK, Pipko SE, Konovets AI, Sadkova IV, Tolmachev A. Acs Comb Sci. 2014;16:192–197. doi: 10.1021/co400164z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Matejka L. Macromolecules. 2000;33:3611–3619. [Google Scholar]; b) Wang XL, Yin JJ, Wang XG. Macromolecules. 2011;44:6856–6867. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gembus V, Marsais F, Levacher V. Synlett. 2008:1463–1466. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) King JF. Accounts Chem Res. 1975;8:10–17. [Google Scholar]; b) King JF, Durst T. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:287–288. [Google Scholar]

- 19.K. B. Sharpless, J. Dong, B. Gao, P. Wu, H. Wang, WO20162099A1, 2016.

- 20.Sun HR, DiMagno SG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2050–2051. doi: 10.1021/ja0440497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subbarao SN, Yun YH, Kershaw R, Dwight K, Wold A. Inorg Chem. 1979;18:488–492. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng J, Zhuo RX, Zhang XZ. Prog Polym Sci. 2012;37:211–236. [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Gauthier MA, Gibson MI, Klok HA. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2009;48:48–58. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Boaen NK, Hillmyer MA. Chem Soc Rev. 2005;34:267–275. doi: 10.1039/b311405h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Chalker JM, Wood CSC, Davis BG. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16346–16347. doi: 10.1021/ja907150m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Spicer CD, Triemer T, Davis BG. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:800–803. doi: 10.1021/ja209352s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gao ZH, Gouverneur V, Davis BG. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:13612–13615. doi: 10.1021/ja4049114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.a) Lowe AB. Polymer Chemistry. 2014;5:4820–4870. [Google Scholar]; b) Xu JT, Boyer C. Macromolecules. 2015;48:520–529. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W, Hong SL, Tran A, Jiang H, Triano R, Liu Y, Chen X, Wu P. Chem-Asian J. 2011;6:2796–2802. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golas PL, Matyjaszewski K. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1338–1354. doi: 10.1039/b901978m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.