Abstract

Introduction: Cannabis sativa (hemp) seeds are popular for their high nutrient content, and strict regulations are in place to limit the amount of potentially harmful phytocannabinoids, especially Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC). In Canada, this limit is 10 μg of Δ9-THC per gram of hemp seeds (10 ppm), and other jurisdictions in the world follow similar guidelines.

Materials and Methods: We investigated three different brands of consumer-grade hemp seeds using four different procedures to extract phytocannabinoids, and quantified total Δ9-THC and cannabidiol (CBD).

Discussion: We discovered that Δ9-THC concentrations in these hemp seeds could be as high as 1250% of the legal limit, and the amount of phytocannabinoids depended on the extraction procedure employed, Soxhlet extraction being the most efficient across all three brands of seeds. Δ9-THC and CBD exhibited significant variations in their estimated concentrations even from the same brand, reflecting the inhomogeneous nature of seeds and variability due to the extraction method, but almost in all cases, Δ9-THC concentrations were higher than the legal limit. These quantities of total Δ9-THC may reach as high as 3.8 mg per gram of hemp seeds, if one were consuming a 30-g daily recommended amount of hemp seeds, and is a cause for concern for potential toxicity. It is not clear if these high quantities of Δ9-THC are due to contamination of the seeds, or any other reason.

Conclusion: Careful consideration of the extraction method is very important for the measurement of cannabinoids in hemp seeds.

Keywords: : cannabidiol, Cannabis sativa seeds, hemp seeds, overdose, phytocannabinoid extraction, tetrahydrocannabinol

Introduction

Cannabis spp. of plants produce a unique class of compounds called cannabinoids. Hemp is a variety of the Cannabis sativa plant species that is grown specifically for the industrial uses of its derived products.1–3 This plant can be refined into a variety of commercial items, including food, and animal feed. C. sativa species leads to both medical cannabis and industrial hemp, and this species contains the psychoactive component Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC); these two plants are two distinct strains with unique phytochemical signatures.1 Hemp has lower concentrations of Δ9-THC, thus limiting its psychoactive effects, and its concentration is regulated in the consumer products where hemp is legal.4,5 The seeds of hemp are rich in unsaturated fats and protein, while containing little to no cholesterol. In fact, a 100 g serving of seeds meets up to 63% of the recommended daily value for protein.6 Whether in the raw seed form or as a derived product such as cold-pressed seed oil, hemp seeds have become increasingly popular as both food and health supplements; in 2011, the United States alone spent more than $11 million on hemp imports for consumption. In most nutritional food stores and grocery stores, hemp seeds are a staple nowadays, in countries where it is legal.

Hemp seeds produce negligible, if any, quantities of THC endogenously.7 While food-grade strains of hemp must contain less than 0.3% Δ9-THC by weight (whole plant), they may not be free of this compound entirely. During the harvesting process, hemp seeds may become contaminated by material from other parts of the plant (such as the Δ9-THC-rich trichomes on flowers) and thus acquire Δ9-THC onto their outer shells.7 Exposure to high concentrations of Δ9-THC could lead to psychological events and gastrointestinal disorders, including acute toxic events such as sedation. In Switzerland, four patients suffered psychological and gastrointestinal issues due to consumption of hemp seed oil, which had higher concentrations of Δ9-THC, prompting public health inquiry.8 A recent case of Δ9-THC poisoning was reported in a toddler who was on a prescription of hemp seed oil to strengthen the immune system.9 The toddler exhibited symptoms such as stupor and low stimulatability, which are characteristic of Δ9-THC intoxication.

In Canada, the Δ9-THC content of hemp products is tightly regulated.5 The Industrial Hemp Regulation (IHR) Program only permits the importation, exportation, sale, and provision of hemp seeds and its derivatives that contain less than 10 μg of THC per gram of food-grade hemp seeds for consumption.5 Products that exceed this threshold are regulated similar to medical cannabis under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, under Narcotics Control Regulations with strict monitoring.10

We were interested in investigating various chemical procedures that one could employ to extract natural products, effect of solvents in these extraction methods, and ultimately the estimation of various compounds in the extract. In this context, we were interested in studying the extraction of hemp seeds to estimate the amount of Δ9-THC, and if the extraction method could influence the estimation in commercial hemp seed. In this study, we report the extractions and analyses of three food-grade hemp seeds, the potential for underestimation of the controlled substance Δ9-THC, and the variability one might encounter due to the differences in extraction efficiencies, and discuss the bearing of these results onto public safety.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Three brands (brand# 1, 2 and 3) of hemp seeds were purchased from local supermarkets in Toronto, Canada, and were used as such in the laboratory experiments. All experiments, including extractions and analyses, were conducted under the appropriate Controlled Drugs Substances Dealer License granted to University Health Network. For ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) analysis, HPLC-grade methanol and MilliQ® water were used for the preparation of the eluents. A Biotage® Initiator microwave was employed for all microwave-related experiments. Sample solutions were analyzed on a Waters® ACQUITY UPLC H-Class System equipped with Quaternary Solvent Manager, Sample Manager FTN, and Acquity UPLC® BEH column (2.1×50 mm, C18, 1.7 μm). A Waters MS 3100 mass spectrometer was used to monitor the samples in both the positive (ES+) and negative (ES−) modes. The injection plate and column were maintained at 15°C and 40°C, respectively. Cerilliant® standards for Δ9-THC, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (Δ9-THCA), cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), and CBD were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich® as Certified Reference Standards in the form of 1.0 mg/mL solutions in methanol or acetonitrile.

Extraction

Four extraction methods were used to extract resins from three brands of food-grade hemp seeds. Each brand of hemp seeds was subjected to each extraction procedure thrice to assess any variability that might arise from the extraction procedure itself. Yields of resin obtained are based on the reweighed seeds.

1. Microwave extraction. Hemp seeds (1 g) were macerated in a mortar using a pestle, reweighed and then transferred into a vial, and suspended in ethanol (10 mL). The vial was sealed and the suspension was heated in a microwave to 150°C with stirring at 900 rpm for 20 min. The suspension was allowed to cool to room temperature and filtered on a pad of Celite® (2 g) and activated carbon (0.25 g). Solids were washed with additional solvent, and all fractions were concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure at 25°C to obtain a sticky resin (yield: 27–38%).

2. Sonication. Hemp seeds (1 g) were macerated, reweighed, and then transferred to a beaker. The macerated seeds were suspended in ethanol (26 mL), and the suspension was sonicated for 20 min after which the solvent was decanted. The sonication was repeated two additional times, collecting the solvent by decantation, refilling with an equivalent amount of solvent, and a 10-min break between each sonication session. All decanted solvent fractions were combined and filtered on a pad of Celite (1 g) and activated carbon (0.25 g). The solids were washed with additional solvent and concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure at 25°C to obtain a sticky resin (yield: 23–40%).

3. Soxhlet extraction. Hemp seeds (2 or 3 g) were macerated with a mortar and pestle, reweighed, and transferred into a cellulose extraction thimble (43×123 mm; 2 mm thickness). The thimble was placed in a Soxhlet extractor (size: 55/50), and ethanol (350 mL) was added to the extractor and refluxed for 4 h. Crude extract was then cooled to rt, and concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure at 25°C to obtain an oily resin (yield: 24–38%).

4. Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE). Hemp seeds (1 or 2 g) were macerated with a mortar and pestle, reweighed, and transferred to an extraction vessel. The extraction was performed using supercritical CO2 as solvent A and ethanol as solvent B. The photodiode array detector was used to monitor the extract, with the range set to 200–600 nm. The back-pressure regulator was set to 12 MPa for the SFE, and other conditions include the following: flow rate=10 mL/min for both CO2 and slave pumps, and 1 mL/min for the make-up pump; temperature=40°C; and gradient: 0–25 min: solvent A, 100%→50%, and solvent B, 0%→50%; 25–26 min: solvent B, 100%; and 26–30 min: solvent A, 100%. The acquisition time was 30 min and the total run time was 30.2 min. All fractions were combined and concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure at 25°C to obtain the extract as a resin (yield: 31–37%).

Extracts in the form of concentrated resins were used as such for the analysis and quantification of cannabinoids. A 10 mg/mL stock solution of the resin was prepared with a 70:30 methanol:water solution with 0.1% formic acid. A 100 μL aliquot of the stock solution was then diluted with 100 μL of mobile phase (70% MeOH in water, with 0.1% formic acid) and filtered to obtain a 5 mg/mL sample solution for analysis.

Analysis

Sample injection volume was 10 μL, at a mobile phase flow rate of 0.6 mL/min for a total run time of 6 min. Two mobile phases, water/0.1% formic acid (phase A), and methanol/0.1% formic acid (phase B), were used and gradient conditions were used for elution: 0–4.5 min: 30%→0% phase A and 70%→100% phase B, 4.5→5 min: 100% phase B, and 5→6 min: 30% phase A and 70% phase B. Internal standard was benzophenone (10 μg/mL solution in MeOH), and each sample was spiked with 9.6 μL of internal standard before analysis. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Quantification

Chromatograms were obtained from the 315 ES+ and 357 ES− single ion recordings (SIRs). Signals on the chromatograms at retention times of 2.73 min (Δ9-THC) and 1.83 min (CBD) in the ES+ mode as well as 3.48 min (Δ9-THCA) and 1.95 min (CBDA) in the ES− mode were integrated to determine the areas-under-the-curves (AUCs) for each phytocannabinoid. In addition, AUC of the internal standard was obtained from the signal at 0.55 min in the 183 ES+ SIR and used in the analyses.

Interpretation

All extracts were analyzed for the concentrations of Δ9-THC, Δ9-THCA, CBDA, and CBD. Thus, concentration standard curves for Δ9-THC, CBD, Δ9-THCA, and CBDA were generated using the respective cannabinoid standards of various concentrations and internal standard (Supplementary Fig. S1). These standard curves were used to estimate the concentrations of the above analytes in the extracts. Lower limits of detection for Δ9-THC, Δ9-THCA, CBD, and CBDA are 1.0, 1.0, 2.5, and 1.0 ng/mL, respectively, and the lower limits of quantitation are 2.5, 2.5, 5.0, and 2.5 ng/mL, respectively.

Results and Discussion

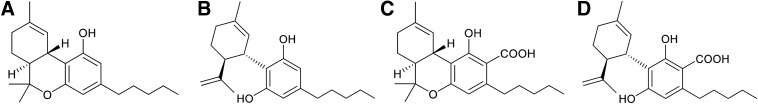

Commercial hemp seeds are marketed for their high nutritional values, but due to their relationship to Cannabis spp. of plants, there is a potential for the presence of phytocannabinoids in these seeds. By regulation, total amount of Δ9-THC (whether in its acid form, Δ9-THCA, or as neutral Δ9-THC) must be less than 10 μg/g of hemp seeds (10 ppm) in Canada, and similar regulations exist in other countries where hemp seeds are legal. Hemp seeds from three brands in local supermarkets were purchased and brought to the laboratory. Each brand of hemp seeds was subjected to four different extraction protocols, and each protocol was repeated thrice to account for any variability due to the extraction procedures and associated errors. In total, 36 extracts were obtained from the three brands and analyzed using UPLC-mass spectrometry to quantify the two major phytocannabinoids, Δ9-THC and CBD. We expected the quantity of Δ9-THC to be within the regulation limits and CBD to be in relatively higher quantities, as one would expect in hemp seeds. As it is common in the Cannabis spp. plants, majority of phytocannabinoids such as Δ9-THC and CBD exist in their carboxylic acid precursor forms, Δ9-THCA and CBDA (Fig. 1). Subjecting the extract or resin to high degree of temperature converts these acid precursors into decarboxylated forms, Δ9-THC and CBD. However, we calculated the total Δ9-THC equivalency (including Δ9-THCA and Δ9-THC found in each extract) to assess the total concentrations; similar procedure was used for the total concentration of CBD.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of (A) Δ9-THC, (B) CBD, (C) Δ9-THCA, and (D) CBDA. THCA, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid.

Extraction methods employed in this investigation utilize somewhat different principles to extract the phytocannabinoids from the hemp seeds into the solvent. Microwave-based extraction method used ethanol as the solvent, but at temperatures up to 150°C with stirring; majority of the acid forms, Δ9-THCA and CBDA, would be converted into the corresponding neutral forms, Δ9-THC and CBD, due to exposure to high temperature. This extraction process is also expected to offer high solubility to the phytocannabinoids due to heating to higher temperatures. Sonication was conducted at an ambient temperature using ethanol as the solvent, and is expected to help release compounds from the plant materials. SFE was conducted using a mixture of supercritical CO2 and ethanol as solvent, at high pressures, but temperature was maintained at 40°C; thus, the extraction efficiency depended on the solubility of phytocannabinoids in supercritical CO2 and ethanol mixture. Most exhaustive extraction, due to high temperature and long extraction time, is likely to be Soxhlet extraction, which was performed at the reflux temperatures in ethanol and for up to 4 h. Among these four methods, one would anticipate the highest yield of phytocannabinoids from Soxhlet extraction. Since ethanol was used in all these extraction methods, differences in extracted quantities of phytocannabinoids can be attributed to the extraction methods themselves.

The concentrations of Δ9-THC, Δ9-THCA, CBD, and CBDA, along with total Δ9-THC (i.e., Δ9-THC + Δ9-THCA) and total CBD (CBDA + CBD) from each brand of hemp seeds, using each of the four extraction procedures, are shown in Table 1, and are plotted in Figure 2. The discussion and interpretations henceforth are in the context of total Δ9-THC and total CBD.

Table 1.

Estimated Concentrations of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol in the Hemp Seeds (in μg/g of Hemp Seeds)

| Brand# | Extraction method | Δ9-THC | Δ9-THCA | Total Δ9-THC | CBD | CBDA | Total CBD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Microwave | 95±44 | 20±11 | 115±55 | 224±109 | 3±3 | 227±111 |

| Sonication | 54±14 | 16±12 | 70±26 | 27±9 | 197±44 | 224±51 | |

| Soxhlet | 66±28 | 13±4 | 79±32 | 60±34 | 157±68 | 217±102 | |

| SFE | 97±33 | 29±24 | 126±57 | 49±13 | 174±93 | 223±106 | |

| 2 | Microwave | 16±13 | 1±1 | 17±14 | 2±4 | 1±0 | 3±4 |

| Sonication | 63±96 | 5±5 | 68±101 | 18±27 | 71±99 | 89±126 | |

| Soxhlet | 37±5 | 17±8 | 54±13 | 16±2 | 69±19 | 85±21 | |

| SFE | 63±7 | 12±5 | 75±12 | 13±4 | 159±27 | 172±31 | |

| 3 | Microwave | 10±4 | 1±0 | 11±4 | 6±9 | 1±0 | 7±9 |

| Sonication | 13±5 | 2±1 | 15±6 | 8±6 | 12±8 | 20±14 | |

| Soxhlet | 44±7 | 47±21 | 91±28 | 54±36 | 36±15 | 90±51 | |

| SFE | 19±3 | 4±1 | 23±4 | 9±7 | 13±2 | 21±9 |

Total THC and total CBD are the total observed weights of THC and THCA, and CBD and CBDA.

CBD, cannabidiol; CBDA, cannabidiolic acid; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol; THCA, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid.

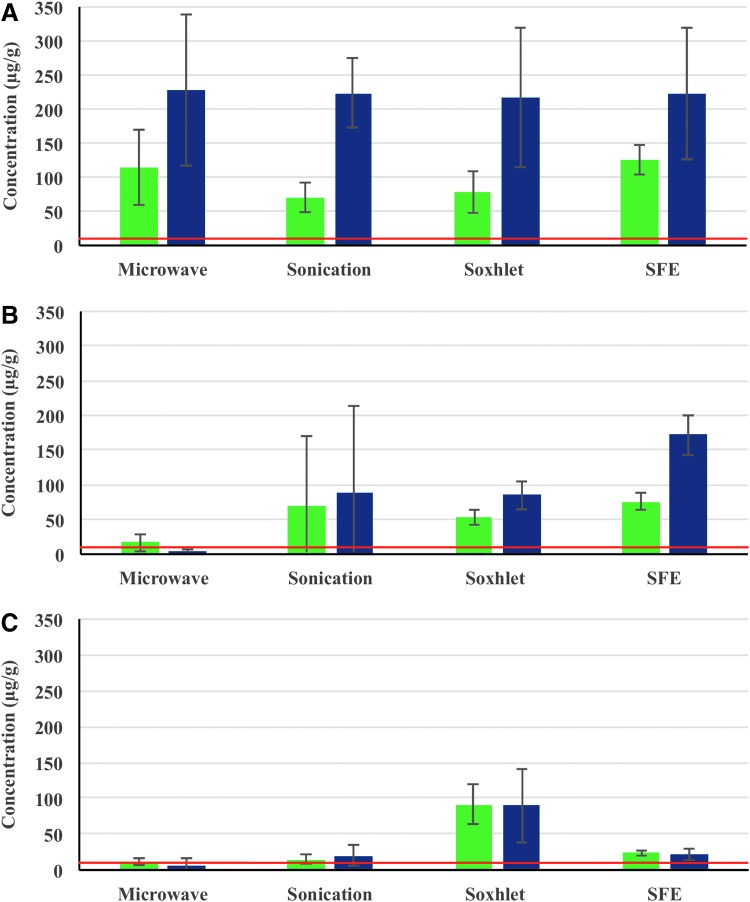

FIG. 2.

Total Δ9-THC (green bars) and CBD (blue bars) content (μg/g of hemp seed) in the consumer-grade hemp seeds, in brand# 1 (A), brand# 2 (B), and brand# 3 (C). Legal limit of Δ9-THC per gram of hemp seeds (as per Health Canada) is shown as a horizontal red line. CBD, cannabidiol; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

We observed large standard deviations associated with each extraction of the same brand of seeds. Each extraction was performed thrice to be able to assess the experimental variability during extraction, and based on this large standard deviation, it appears that the extracts could show reasonable variability in the assessed phytocannabinoids, and this deviation may also be due to the nonhomogenous hemp seed bulk material. Either way, these variations warrant the analysis of multiple samples of hemp seed from different parts of the bulk material to assess total amount of phytocannabinoids, as accurately as possible. For brand# 1, all four extraction methods yielded approximately similar phytocannabinoids concentrations, that is, total Δ9-THC and CBD (Fig. 2A). Total CBD concentration ranged from 217±102 to 227±111 μg/g, and all four methods of extraction viz. microwave-based extraction, sonication, SFE, and Soxhlet extraction yielded similar results. Total CBD is expected to be relatively higher in concentration in hemp seeds and is reflected in these measurements. Total Δ9-THC has shown some variation based on the extraction method: sonication and Soxhlet extractions showed the amount of total Δ9-THC to be 70±26 and 79±32 μg/g, whereas microwave and SFE extracts showed 115±55 and 126±57 μg/g, respectively (Table 1). At the outset, all four quantities are several fold higher than the regulatory limits on Δ9-THC quantities in hemp seeds in Canada (red line in Fig. 2A), and depending on the method employed for extraction, the estimation of Δ9-THC would be 7- to 12-fold higher than the legal limit (10 μg/g of hemp seeds in Canada).

Extractions of brand# 2 hemp seeds exhibited more variance, where total Δ9-THC amounts were estimated to be 68±101, 54±13, and 75±12 μg/g of hemp seeds using sonication, Soxhlet, and SFE extractions respectively, all of which are fivefold to sevenfold higher than the permitted limit (Fig. 2B), whereas microwave extraction estimated the total Δ9-THC content to be 17±14 μg/g only. Variations on the CBD estimates are even more significant, where the variation ranged from 3±4 μg/g (using microwave technology) to 172±31 μg/g (SFE) of hemp seeds. It is interesting to note that a different brand led to a completely different profile in the phytocannabinoid variations (brand# 1 vs. 2), and the results based on the extraction method employed are different as well.

For brand# 3, three extraction methods concurred with the estimation of the phytocannabinoids, viz. microwave extraction, sonication, and SFE estimated the CBD in the rage of 7±9 μg/g to 21±9 μg/g, and total Δ9-THC content in the range of 11±4 to 23±4 μg/g hemp seeds (Fig. 2C). However, Soxhlet extraction indicated that the amount of CBD and total Δ9-THC in brand# 3 hemp seeds to be 90±51 and 91±28 μg/g of hemp seeds, respectively. While the former estimations indicate that total Δ9-THC is closer to the legal limit in hemp seeds, the latter method indicated it to be up to nine folds higher than the legal limit, and this is a significant difference. Overall, none of the brands using any of the methods could convincingly be confirmed that the total Δ9-THC content is within the legal limits of 10 μg/g of hemp seeds. It is also noted that the phytocannabinoid content exhibited a significant variation even among batches from the same brand, reflecting both the inhomogeneous nature of seeds as well as the variations in quantification based on the extraction process.

According to Health Canada's Industrial Hemp Technical Manual, the current approved procedure of Δ9-THC quantification in hemp involves the sonication of 3 g of dried leaf powder in hexanes followed by analysis by gas chromatography.11 There is no mention of testing procedures for any other parts of the hemp plant, including its seeds. Using a similar hexane-sonication procedure, quantification conducted by Ross et al., obtained Δ9-THC concentrations of 0–12 μg/g for fiber-type cannabis seeds.7 In this study, ethanolic extraction using sonication exhibited significant variation from 17% to 92% of the maximum yield across the three brands of hemp seeds. This inconsistency could be attributed to the higher oil content within hemp seeds compared to the rest of plant. Due to hydrophobicity of the Δ9-THC molecule, it is expected to partition more strongly into the seed material, leading to the gross underestimation of Δ9-THC content by sonication.

Δ9-THC is a nonselective partial agonist of the CB1 and CB2 receptors, and elicits a variety of physiological effects, including analgesia, appetite stimulation, motor neuron inhibition, and CNS sedation, when bound to CB1.12 Δ9-THC is highly potent and has a Ki <50 nM for both CB1 and CB2 in humans.13 In a study involving adult males who were infrequent users of cannabis, a 15 mg oral dose of THC was found to impair episodic memory and increase task error rates, 2 h after its administration.14 Based on the results obtained in this study, 120 g of hemp seeds from brand# 1 could contain an equivalent quantity of 15±3 mg of total Δ9-THC, using the quantity estimates from SFE. Suggested serving size for an adult for most consumer brands of hemp seeds is 30 g, and this is equivalent to 3.8±0.6 mg of total Δ9-THC, when using brand# 1 hemp seeds. It is also noted that a significant portion of the total Δ9-THC content exists in the form of the acid precursor Δ9-THCA, which is not known to exhibit psychoactivity.15 However, exposure to heat (due to cooking or other reasons) could always generate Δ9-THC. However, in the absence of strong heating, the seeds' effective Δ9-THC concentration is expected to be lower than their total Δ9-THC content, lowering the risk of acute phytocannabinoid poisoning from direct consumption. Chinello et al. reported a case of subacute poisoning from the sustained consumption of a relatively Δ9-THC-poor product by a toddler.9 Such subacute poisoning is always a possibility when hemp seeds carry higher quantities, such as 10- and 12-fold higher than the recommended limits, or the concentrations of Δ9-THC are not estimated accurately.

In an earlier study, Ross et al. conducted an investigation to determine Δ9-THC content in drug- and fiber-type (hemp) cannabis seeds.7 Hemp seeds in this study were found to contain 0–12 μg Δ9-THC per 1 g of seeds, but Δ9-THC in drug-type cannabis seeds was in much higher levels (35.6–124 μg/g). It was found that majority of Δ9-THC was located on the surface of the seeds, and a wash with chloroform removed upto 90% of Δ9-THC. It was suggested that fluctuations in the Δ9-THC content of different replicates of the same type of seeds could be the result of the degree of contamination on the outside of the seeds. In this study of consumer-grade hemp seeds acquired from the grocery stores, highly variable, but above the legal limit of, Δ9-THC may suggest either contamination by drug-type cannabis seeds or improper washing of the seeds.

Δ9-THC primarily undergoes liver metabolism through CYP3A4 and CYP2C9.16 Due to the polymorphic nature of P450 enzymes,17,18 people consuming hemp seeds may gradually accumulate Δ9-THC due to its slow metabolism or relatively long half-life in the body, leading to potentially higher concentrations. In the report by Chinello et al., Δ9-THC concentration in the prescribed hemp seed oil was 0.06%, that is, 0.6 mg of total Δ9-THC in 1 g of hemp seed oil, and the child was administered two teaspoons (∼10 mL or 9.2 g) a day for 3 weeks before the incidence of neurological symptoms.19 This amounts to 5.52 mg total Δ9-THC per day, when one consumes 10 mL above hemp seed oil. If one were to compare these total Δ9-THC levels, a similar quantity of total Δ9-THC (5.52 mg) is contained in ∼44.2 g of hemp seeds (brand# 1, total Δ9-THC estimate based on SFE extraction), and this is certainly a normal quantity that consumers may consume as part of their daily food consumption. In people with liver impairment or patients consuming other drugs such as ketoconazole (an inhibitor of CYP3A4) or sulfaphenazole (an inhibitor of CYP2C9), one would expect the metabolism of Δ9-THC to be slower, and would be at risk for adverse effects upon the consumption of hemp seeds with higher concentrations of total Δ9-THC.16,20,21 However, we note that the bioavailability of Δ9-THC is only 10−20% and could vary if consumed along with fatty food, and such factors would influence the plasma levels of Δ9-THC.22–24

The other major phytocannabinoid in hemp, CBD, is an antagonist of CB1 and CB2 with relatively weak binding affinities.12 While CBD is not known to exhibit psychoactive properties, CBD can be cyclized into Δ9-THC when incubated with artificial gastric juice at 37°C.25 Given that CBD was present in generally higher amounts than Δ9-THC, the conversion of CBD into Δ9-THC in the stomach after consumption may further contribute to the psychoactivity of hemp seeds.

Conclusion

In comparison, Soxhlet extraction provided consistently higher yields of Δ9-THC, although it takes longer time than other methods for extraction. This suggests the importance of heating and prolonged solvent cycling in extracting phytocannabinoids from lipid-rich materials such as hemp seeds. Δ9-THC concentrations of up to 125 μg/g of hemp seed were found in food-grade hemp seeds, and all evaluated brands contained higher amounts than the legal threshold of 10 μg Δ9-THC per gram of hemp seeds. Exposure to higher amounts of Δ9-THC may cause neurological symptoms especially for poor metabolizers of cannabinoids. It would be presumptuous to conclude the source of this excessive Δ9-THC in the consumer-grade hemp seeds, but could be either contamination during harvesting/processing of the seeds or higher levels of biosynthesis, which is unlikely. Current methods for validating Δ9-THC content in hemp may be providing lower and/or inconsistent yields for hemp seeds and could lead to the underestimation of Δ9-THC content. A more robust extraction methodology such as Soxhlet extraction may be more appropriate for the testing of hemp seed products. One may also consider employing washing of hemp seeds with ethanol or other similar solvents, to remove any contamination to the seeds before packaging; but such change from current practice and new processes must be thoroughly investigated before implementation for consumer marketing. Based on the above findings, it is also recommended that the hemp seeds be analyzed specifically for phytocannabinoid content before release into consumer markets.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- AUC

area-under-the-curve

- CBD

cannabidiol

- CBDA

cannabidiolic acid

- IHR

Industrial Hemp Regulations

- SFE

supercritical fluid extraction

- SIR

single ion recording

- UPLC

ultra performance liquid chromatography

- Δ9-THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- Δ9-THCA

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid

Acknowledgments

L.P.K. gratefully acknowledges the financial support from Canada Foundation for Innovation (grant no. CFI32350), Ontario Research Fund, University Health Network, and Scientus Pharma (formerly CannScience Innovations, Inc.). H.A.C. is supported by a Merit Award from the Department of Anesthesia, University of Toronto.

Author Disclosure Statement

L.P.K. and H.A.C. serve on the scientific and medical advisory board of Scientus Pharma, Inc. and receive a consulting fee.

References

- 1.Swanson TE. Controlled substances chaos: the Department of Justice's New Policy Position on Marijuana and what it means for industrial hemp farming in North Dakota. North Dakota Law Rev. 2015;90:599–622 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemp. American history revisited: the plant with a divided history. Ed.: Deitch R. Algora Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2003, p. 219 (ISBN 978-0-87586-226-2) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pertwee RG. Handbook of cannabis. Oxford University Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Specialty oils and fats in food and nutrition: properties, processing and applications. Ed.: Talbot G. Elsevier Science: New York, 2015, p. 39 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Industrial Hemp Regulations (SOR/98-156). Department of Justice, Canada, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Full Report (All Nutrients): 12012, Seeds, hemp seed, hulled. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28, 2016

- 7.Ross SA, Mehmedic Z, Murphy TP, et al. . GC-MS analysis of the total Δ9-THC content of both drug- and fiber-type cannabis seeds. J Anal Toxicol. 2000;24:715–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier H, Vonesch HJ. Cannabis poisoning after eating salad. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1997;127:214–218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinello M, Scommegna S, Shardlow A, et al. . Cannabinoid poisoning by hemp seed oil in a child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:344–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frequently Asked Questions about Hemp and Canada's Hemp Industry. Health Canada, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Industrial Hemp Technical Manual—Standard Operating Procedures for Sampling, Testing and Processing Methodology. Health Canada, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill AJ, Williams CM, Whalley BJ, et al. . Phytocannabinoids as novel therapeutic agents in CNS disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:79–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gertsch J, Pertwee RG, Di Marzo V. Phytocannabinoids beyond the Cannabis plant—do they exist? Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:523–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curran HV, Brignell C, Fletcher S, et al. . Cognitive and subjective dose-response effects of acute oral Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in infrequent cannabis users. Psychopharmacology. 2002;164:61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izzo AA, Borrelli F, Capasso R, et al. . Non-psychotropic plant cannabinoids: new therapeutic opportunities from ancient herb. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:515–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe K, Yamaori S, Funahashi T, et al. . Cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of tetrahydrocannabinols and cannabinol by human hepatic microsomes. Life Sci. 2007;80:1415–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiratsuka M. In vitro assessment of the allelic variants of cytochrome P450. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2012;27:68–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou SF, Liu JP, Chowbay B. Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 enzymes and its clinical impact. Drug Metab Rev. 2009;41:89–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Density for hemp oil is considered to be approximately 0.92 g/mL. Ref: Bailey's industrial oil & fat products. 6th edition. Wiley-Intersience: New York, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsunaga T, Kishi N, Higuchi S, et al. . CYP3A4 is a major isoform responsible for oxidation of 7-hydroxy-Delta(8)-tetrahydrocannabinol to 7-oxo-delta(8)-tetrahydrocannabinol in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:1291–1296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stott C, White L, Wright S, et al. . A Phase I, open-label, randomized, crossover study in three parallel groups to evaluate the effect of Rifampicin, Ketoconazole, and Omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics of THC/CBD oromucosal spray in healthy volunteers. Springerplus. 2013;2:23–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wall ME, Sadler BM, Brine D, et al. . Metabolism, disposition, and kinetics of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in men and women. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;34:35–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huestis MA. Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics. Chem Biodiv. 2007;4:1770–1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zgair A, Wong JC, Lee JB, et al. . Dietary fats and pharmaceutical lipid excipients increase systemic exposure to orally administered cannabis and cannabis-based medicines. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:3448–3459 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe K, Itokawa Y, Yamaori S, et al. . Conversion of cannabidiol to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and related cannabinoids in artificial gastric juice and their pharmacological effects in mice. Forensic Toxicol. 2007;25:16–21 [Google Scholar]

References

Cite this article as: Yang Y, Lewis MM, Bello AM, Wasilewski E, Clarke HA, Kotra LP (2017) Cannabis sativa (hemp) seeds, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and potential overdose, Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 2:1, 274–281, DOI: 10.1089/can.2017.0040.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.