Abstract

Background

Ethnic minorities remain underrepresented in clinical trials despite efforts to increase their enrollment. Although community-based participatory research (CBPR) approaches have been effective for conducting research studies in minority and socially disadvantaged populations, protocols for CBPR recruitment design and implementation among immigrants and refugees have not been well described.

Methods

We used a community-led and community-implemented CBPR strategy for recruiting 45 Hispanic, Somali, and Sudanese families (160 individuals) to participate in a large, randomized, community-based trial aimed at evaluating a physical activity and nutrition intervention.

Results

We achieved 97.7% of our recruitment goal for families and 94.4% for individuals.

Discussion

Use of a CBPR approach is an effective strategy for recruiting immigrant and refugee participants for clinical trials. We believe the lessons we learned during the process of participatory recruitment design and implementation will be helpful for others working with these populations.

Keywords: CBPR, immigrants, randomized trial, recruitment, refugees

Introduction

Racial or ethnic minorities comprise nearly 30% of the US population (1), among which, immigrants and refugees account for 13% of the total population (2). Inclusion of minority participants in clinical trials is important in generating research that more accurately represents the US population (3), however, recruitment of these populations remains challenging. Factors impacting recruitment are often complex (4) and multifaceted, and thus, approaches that account for, and mitigate barriers to enrollment are needed.

Utilizing a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach has been effective for addressing issues of health disparity in minority populations (5, 6) and has been especially advantageous in working with immigrants and refugees (7, 8). However, there is relatively little written about CBPR recruitment design, and we are not aware of any published articles that report participatory recruitment among immigrants and refugees. To address this gap, we describe lessons learned from participatory recruitment of immigrants and refugees to a randomized, community-based trial in Rochester, Minnesota.

Methods

Rochester Healthy Community Partnership (RHCP) is a community-academic partnership that started in 2004, with the mission of promoting health and well-being and achieving health equity among the Rochester, Minnesota community through CBPR, education, and civic engagement. In 2011, RHCP received federal funding for a CBPR project with and for immigrants and refugees.

CBPR Study

Healthy Immigrant Families: Working together to Move more and Eat Well was collaboratively designed and implemented by RHCP community and academic partners to develop, implement and evaluate a sustainable, socioculturally appropriate physical activity and nutrition intervention with and for Somali, Sudanese and Latino immigrant and refugee families, via a community-based randomized trial. The intervention consisted of 12 home-based family mentoring and education sessions delivered over six-months by language-congruent Family Health Promoters (FHPs). Assessments were conducted at baseline, 6, 12 and 24 months. Primary outcomes included changes in physical activity, measured by accelerometery, and in dietary quality, measured by 24-hour dietary recall.

Criteria for inclusion existed at both family and individual levels. A family was defined as 2 or more persons in the same household who self-identified as a family. To be eligible, a family had to have at least 1 adult, 19 years or older, and at least 1 child, 10 to 18 years. Individuals were excluded for 1) pregnancy, 2) insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, 3) diagnosis of cancer within three years, and 4) answering yes to the question: “Do you know of any reason why you should not do physical activity?” Participants gave oral consent and, when applicable, assent.

Development of a Recruitment Strategy

Recruitment for this study was entirely community based and community driven. A workgroup comprised of representative community and academic partners developed socioculturally appropriate recruitment messaging, identified effective communication methods specific to each community, and generated ideas for incentives. This workgroup met regularly for a year, and products and ideas were presented and agreed on during a series of research summits.

Recruitment messaging was framed as a means for families to learn more about healthy eating and being physically active from an FHP who spoke their language and understood their culture.

Community-Based Recruitment Team

The recruitment teams were comprised of RHCP community partners (hereafter referred to as recruitment partners) from each of the participating groups. These individuals possessed a nuanced understanding of the language and culture of each of the study populations. Many were associated with local organizations that provide services to immigrant and refugee communities and were therefore experienced in working with these populations.

Pretesting Recruitment Strategies

To refine recruitment strategies and enrollment procedures, we recruited 6 families (16 individuals) for pretesting. Recruitment partners identified and contacted potential families, and facilitated communication with a language-congruent study staff. Study staff provided families with a detailed description of the study, conducted eligibility screening, and invited qualified families to the pretest. On average, study staff made three telephone contacts with each family to remind them about the event, and coordinate last-minute logistical issues, such as transportation and childcare.

Participants were then asked to provide feedback and their perceptions of the recruitment processes. Suggestions included a strong recommendation for more contact with potential participants. Although written recruitment materials were felt to be helpful, participants preferred verbal explanations.

Randomized Trial Recruitment

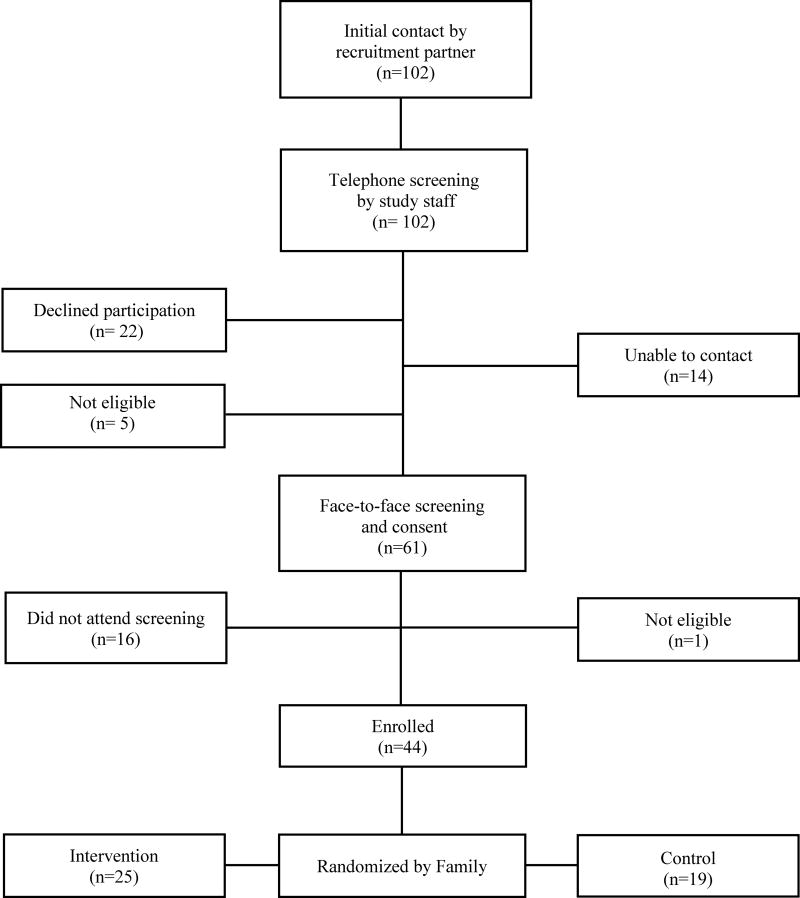

For the randomized trial, our goal was to recruit 45 families (160 individuals) over three months. The Figure diagrams the recruitment process. Similar to pretesting, recruitment partners identified potential families, made initial contacts, and provided a general study description. Interested families were then contacted by a language-congruent study staff who provided more detailed study information, conducted preliminary screening, and offered to meet with families to answer any questions. Families who qualified were invited to a final screening, enrollment, and baseline assessment at a community center. Food, transportation, and childcare were provided, and certified interpreters were available the entire time.

Figure I.

Community-led recruitment of participants (number of families)

Results

Of 17 families identified and contacted for pretesting, 16 families (94.1%) were eligible to participate and 5 (29.4%) were enrolled. For the randomized trial, 102 families were identified and contacted, 70 were eligible, and 44 (151 individuals) were enrolled, achieving 97.7% of the enrollment target for families and 94.4% for individuals. Table 1 summarizes recruitment and enrollment for both pretest and the randomized trial.

Table I.

Pre-test and Randomized Trial Recruitment Summary (number of families)

| Hispanic | Somali | Sudanese | Overall | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Randomized | Pre-test | Randomized | Pre-test | Randomized | Pre-test | Randomized | |

| Contacted | 5 | 61 | 4 | 30 | 8 | 11 | 17 | 102 |

| Eligible | 4 | 36 | 4 | 23 | 8 | 11 | 16 | 70 |

| Enrolled | 1 | 26 | 1 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 44 |

| Contacted vs. Enrolled | 20.0% | 42.6% | 25.0% | 50.0% | 37.5% | 27.2% | 29.4% | 43.1% |

| % Change | +22.6% | +25% | −10.3% | +13.7% | ||||

Of the 151 individuals enrolled, 124 (82.1%) successfully completed 12-month measurements (17.9% attrition [Table 2]). Of the 25 families randomized to receive the intervention, 23 (92%) completed the intervention.

Table II.

Randomized Trial Retention Summary (families and individual participants)*

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Hispanic | 15 (46) | 11 (34) | 14 (41) | 11 (34) | 14 (39) | 11 (33) |

| Somali | 9 (27) | 6 (37) | 8 (23) | 5 (32) | 8 (22) | 4 (23) |

| Sudanese | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Total | 25 (46) | 19 (75) | 23 (67) | 18 (70) | 23 (64) | 17 (60) |

| % Change | −8.0% (−11.9%) | −5.3% (−6.7%) | −8.0% (−15.8%) | −10.5% (−20.0%) | ||

| % Change Overall | −6.8% (−9.3%) | −9.1% (−17.9%) | ||||

Individuals represented in parentheses

Discussion

Engage Community Partners throughout the Research Process

Because of many complex factors impacting research with immigrants and refugees, we found it critical to engage community partners throughout the research process—from protocol development to implementation. Community partners possess an implicit understanding of the language, culture, and social dynamics that exist within their respective communities, and for our study, their leadership was essential for developing effective recruitment and retention strategies.

One way to enhance trust, and thereby, effectiveness, among community and academic partners is through Human Subjects Protection Training (HSPT). We previously reported that community partners who completed HSPT had increased trust, increased awareness and appreciation for the safeguards present in research, and increased trust in the research process itself (9). In this study, we learned that HSPT with community partners not only increased capacity but also contributed to ethical recruitment and promoted methodological rigor.

Early Community-Informed Communication With IRB

During the planning stage of this study, academic and community partners met to discuss socioculturally appropriate means of obtaining consent and assent from participants. Community partners emphasized that written informed consent might not be acceptable for participants, especially for those who recently immigrated to the US, and that oral consent and assent were more appropriate. Study staff worked closely with the IRB in this regard, and obtained approval for using oral consent and assent.

CBPR varies greatly from the typical biomedical research model and, thus, may require IRBs to evaluate these types of studies differently (10). We believe that this variance from standard institutional procedures was important to the success of our recruitment efforts. Requiring the use of standardized written consent and assent documents for these populations would have severely impacted study recruitment and undermined the expertise and cultural insight of community partners. In this instance, the IRB acknowledged the expertise of our community partners and followed their recommendation, allowing for the implementation of a socioculturally acceptable recruitment process and thus, fostered truly informed consent.

Multiple Contacts With Potential Research Participants

Potential participants were contacted at multiple time points by language-congruent study staff and recruitment partners. This process allowed participants to receive study information in a way that was not overwhelming. The recruitment team felt that face-to-face contact with potential participants was instrumental in recruiting within certain communities (Somali and Sudanese families in particular) and that initial contact by a recruitment partner who spoke the same language helped legitimize the study. Participants across all groups required multiple phone calls from the time of initial contact to enrollment (average of four calls per family in the randomized trial). Families were given time to discuss the project among themselves and identify which family members were interested in participating.

Recruitment within the Somali community required more telephone and in-person contacts (average, 10 contacts) compared with the other groups. After the initial contact by a recruitment partner, many Somali families requested an in-person meeting with study staff, and often invited neighbors and friends to be present during the visit. During the face-to-face meetings, study staff demonstrated and explained study procedures and answered questions, enabling potential participants to feel more comfortable about the study and, therefore, to be more inclined to participate in the study.

Research Participants as Advocates for the Study

The Latino, Somali, and Sudanese communities in Rochester, Minnesota are relatively small compared to their counterparts in larger metropolitan areas. Consequently, news often travels fast within these communities. During recruitment for this study, some families initially hesitated to participate. In many cases, these families spoke with their friends and others about the project before agreeing to participate themselves. As a result, more families enrolled during the latter part of the recruitment period of this study. Future studies may benefit from building in additional time for word-of-mouth recruitment.

Conclusion

Community-led recruitment and retention strategies are effective for working with minority populations and can be especially advantageous for working with immigrant and refugee populations. This study described the recruitment of three specific immigrant and refugee groups to a randomized trial, however, the strategies and approaches described here may be applied to other minority and socially disadvantaged groups, and may prove valuable in enhancing minority inclusion and retention across a broad spectrum of research and populations.

Ethics Review Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Church of St John the Evangelist, Winona State University Department of Nursing, Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science, Divanyx Design & Photography, and members of the Rochester Healthy Community Partnership who devoted their time and effort to this project. This study is supported by an award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute (NHLBI), R01-HL 111407-03, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), Clinical and Translational Science Activities Program (CTSA), UL1 TR000135. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- CBPR

community-based participatory research

- FHP

Family Health Promoters

- HSPT

Human Subjects Protection Training

- IRB

institutional review board

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau: 2010 demographic profile data [Internet] [cited 9 Jul 2015];American FactFinder. 2010 Available from: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DP_DPDP1&src=pt.

- 2.Grieco EM, Trevelyan E, Larsen L, Acosta YD, Gambino C, de la Cruz P, et al. The size, place of birth, and geographic distribution of the foreign-born population in the United States: 1960 to 2010. US Census Bureau. 2012 Oct; Population Division Working Paper No. 96. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hohmann AA, Parron DL. How the new NIH guidelines on inclusion of women and minorities apply: efficacy trials, effectiveness trials, and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996 Oct;64(5):851–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birman D. Ethical issues in research with immigrants and refugees. In: Trimble JE, Fisher CB, editors. The handbook of ethical research with ethnocultural populations & communities. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc.; c2006. pp. 155–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.De las Nueces D, Hacker K, DiGirolamo A, Hicks LS. A systematic review of community-based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Serv Res. 2012 Jun;47(3 Pt 2):1363–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01386.x. Epub 2012 Feb 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horowitz CR, Brenner BL, Lachapelle S, Amara DA, Arniella G. Effective recruitment of minority populations through community-led strategies. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Dec;37(6 Suppl 1):S195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Torre A, Sadeghi B, Green RD, Kaiser LL, Flores YG, Jackson CF, et al. Ninos Sanos, Familia Sana: Mexican immigrant study protocol for a multifaceted CBPR intervention to combat childhood obesity in two rural California towns. BMC Public Health. 2013 Oct 31;13:1033. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis BH, Kia-Keating M, Yusuf SA, Lincoln A, Nur A. Ethical research in refugee communities and the use of community participatory methods. Transcult Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;44(3):459–81. doi: 10.1177/1363461507081642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawley NC, Wieland ML, Weis JA, Sia IG. Perceived impact of human subjects protection training on community partners in community-based participatory research. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2014 Summer;8(2):241–8. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross J, Pickering K, Hickey M. Community-based participatory research, ethics, and institutional review boards: untying a Gordian knot. Crit Sociol. 2014 Jun 3; [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]