Abstract

There are many kinds of unusual presentations or associations and clinical mimics of acute appendicitis, and definitive diagnosis requires knowledge of the imaging findings in some cases. The unusual presentations and associations of acute appendicitis included in this study are perforated appendicitis, acute appendicitis occurring in hernias, acute appendicitis with cystic endosalpingiosis, intussusception of appendix, and acute appendicitis with pregnancy. We also present uncommon gastrointestinal, urinary and gynecologic clinical mimics of acute appendicitis including anomalous congenital band, duplication cysts, giant Meckel’s diverticulitis, inflammatory fibroid polyp, renal artery thrombosis, spontaneous urinary extravasation and OHVIRA syndrome. Familiarity with these entities may improve diagnostic accuracy and enable the quickest and most appropriate clinical management.

Keywords: Abdomen, acute appendicitis, mimics, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, diagnosis

Öz

Akut apandisitte olağandışı sunumlar veya birliktelikler ve klinik taklitçilerin birçok türü vardır ve kesin teşhis bazı olgularda görüntüleme bulguları hakkında bilgi gerektirir. Bu çalışmada perfore akut apandisit, hernilerde akut apandisit, kistik endosalpingiosis akut apandisit, apandiks intussusepsiyonu, ve gebelik ile akut apandisit bulunmaktadır. Ayrıca anormal konjenital bant, duplikasyon kistleri, dev Meckel divertikülit, inflamatuar fibroid polip, renal arter trombozu, spontan üriner ekstravazasyon ve OHVIRA sendromu dahil olmak üzere nadir görülen gastrointestinal, idrar ve jinekolojik klinik akut apandisit taklitlerini sunuyoruz. Bu varlıklara aşinalık tanısal doğruluğu artırabilir ve en hızlı ve en uygun klinik tedaviyi sağlayabilir.

Keywords: Karın, akut apandisit, taklitleri, bilgisayarlı tomografi, manyetik rezonans görüntüleme, tanı

Introduction

Acute appendicitis (AA) is one of the most common abdominal emergencies. It is defined as an inflammation of the inner lining of the vermiform appendix that spreads to its other parts. It is usually caused by obstruction of the appendiceal lumen from a variety of causes such as appendicolith, lymphoid hyperplasia of the appendix wall, foreign bodies, parasites, neoplasia, and metastasis. The diagnosis is often made based on clinical, laboratory, and cross-sectional imaging findings. The main imaging findings include the presence of a dilated, thick-walled, blind-ending, tubular structure with a diameter exceeding 6 mm, periappendiceal inflammation, and prominent mucosal enhancement, with or without an appendicolith [1]. However, the definitive diagnosis of the disease can be challenging in unusual presentations or associations, and there are many rare abdominal and pelvic diseases that can mimic AA, complicating its diagnosis [2].

In this pictorial essay, we present a few examples of unusual presentations or associations, and clinical mimics of the disease from our archive with a brief review to familiarize the readers with these imaging appearances. It should be noted that there are many other acute appendicitis mimics that are not mentioned in this text, such as appendicitis with tumors, ovarian pathologies, or gastrointestinal system infections.

Normal anatomy of the appendix

The appendix is derived from the cecal diverticulum as a diverticular outpouching on the antimesenteric side of the caudal midgut loop during the six weeks of gestation. Since the appendix grows in length, but its diameter does not grow as fast as the cecum, it is long and worm-shaped, or vermiform at birth. Although the human appendix arises from the medial-posterior end of the cecum as a thin tube, the position of the appendix can be varied such as retrocecal, retrocolic, or pelvic. The appendix averages 6–8 cm in length, but can have a variable length. It is supplied by the appendicular artery, a terminal branch of the ileocolic artery from the superior mesenteric artery, and the venous blood drains through the correspondent veins into the superior mesenteric vein. Lymphatic drainage is into the ileocolic lymph nodes along the course of superior mesenteric artery [3].

Normal imaging appearance

Ultrasonography, which is a valuable first pass modality for evaluation of the appendix, reveals the organ as a compressible tubular structure. Multidetector computed tomography with multiplanar reformatted images with or without intravenous or oral contrast material is used at many institutions as the initial tool for evaluation of abdominal pain, which may lead to the detection of various pathologies including appendix. When needed, magnetic resonance imaging should be performed with a 1.5 T or a great unit and protocols should include diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging.

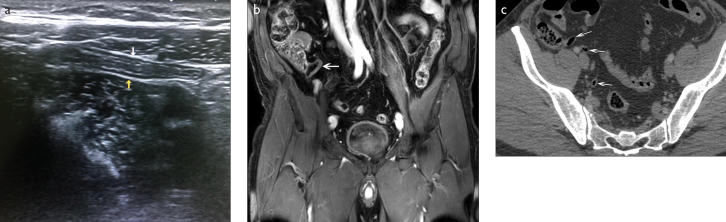

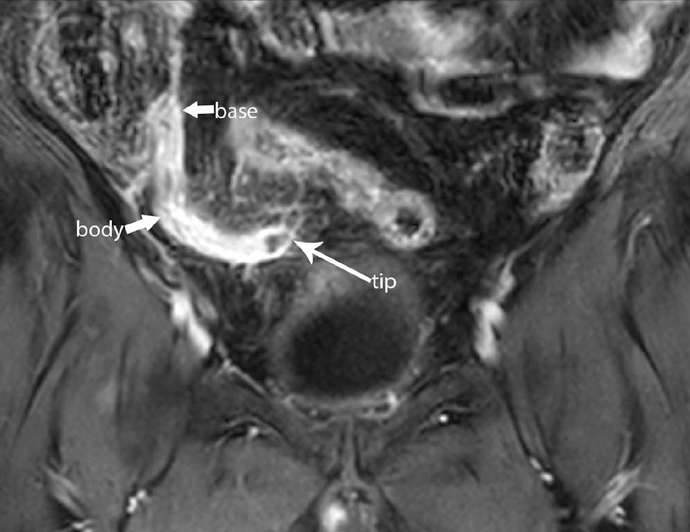

On imaging studies, the three anatomic parts of the appendix should be visualized as a blind-ending tubular structure with thin walls that measures less than 6-mm wall-to-wall diameter. Wall thickness is normally less than 2 mm. The base is attached to the wall of cecum about 2 cm below the ileocecal valve. The body is a thin, tubular part between the base and the tip, which is the distal blind end. The appendix may be filled with feces, air, or contrast material (Figure 1) [4].

Figure 1. a–c.

Normal imaging appearances of appendix on longitudinal real-time ultrasonography scan (a), coronal contrast-enhanced MR image (b), and axial contrast-enhanced CT image (arrows) (c)

Unusual Presentations and Associations

Perforated appendicitis

The diagnosis of perforated appendix is crucial as perforation increases the risk of complication after surgery. Defects in the appendiceal wall, extraluminal air locules or free intraperitoneal air, localised right iliac fossa abscess or phlegmon, and appendicolith outside the appendix or within the right iliac fossa abscess are the main imaging findings of this increasingly rare complication (Figure 2) [5]. It should be mentioned that the appendix may still be ruptured without these imaging findings (Figure 3). Perforated appendicitis may cause complications like abscess formation and peritonitis. The development of peritonitis secondary to perforation is more frequent in children due to rapid progression from inflammation to wall rupture. However, in adults, the inflammatory adhesions developing around the site of inflammation more frequently cause phlegmons and abscesses instead of a rapid evolution in peritonitis. Pylephlebitis and pylethrombosis, hydrouretero-nephrosis; gangrenous appendicitis, dynamic or mechanical bowel obstruction, and fistula with other contiguous organs such as bladder, vagina, uterus, and skin are the other complications that may be detected in the abdominal cavity following appendix perforation [6].

Figure 2.

Sagittal reformatted CT image of the pelvis in a 55-year-old female with new onset acute right lower quadrant pain demonstrates a defect in the thickened enhancing wall of the enlarged appendix, appendicolith inside the appendix (arrowhead), and an extraluminal air (arrow) in the periappendiceal phlegmonous changes due to acute perforated appendicitis

Figure 3.

A perforated appendix from the tip in a 62-year-old man with right lower abdomen pain. Coronal fat-saturated contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI demonstrates intensely enhancing thickened appendix with small abscesses inside and adjacent the tip secondary to rupture (arrow)

Acute appendicitis occurring in hernias

Acute appendicitis can occur in any type of abdominal hernia including the inguinal hernia sac (Amyand’s hernia), the femoral hernia sac (De Garengeot’s hernia), obturator hernia, umbilical hernia, Spigelian hernia, laparoscopic port site hernia, and incisional site hernia. An appendix incarcerated within a hernia makes it vulnerable to trauma and adhesions, further restricting it from sliding back into the abdominal cavity and increasing the risk of inflammation. Acute hernial appendicitis usually creates a diagnostic problem prior to surgery and most often the diagnosis is incarcerated or strangulated hernia. Other considerations may vary due to the site of hernia and may include variable pathologies such as Richter’s hernia, orchitis, omentocele, inguinal lymphadenitis, epidydimitis, and hemorrhagic testicular tumor. Multidetector CT and multiplanar MRI are excellent imaging modalities for elucidating a blind-ending tubular structure arising from the caecum that extends into the hernia sac (Figure 4) [7].

Figure 4.

Sagittal reformatted CT images of the pelvis in a 58-year-old male patient with right lower quadrant abdominal pain and discomfort in the right inguinal region reveal an appendix within a right-sided indirect inguinal hernia-Amyand hernia (arrowhead). There is inflammation at the base of the appendix (arrow). The patient underwent successful appendectomy and hernia repair without mesh

Acute appendicitis with cystic endosalpingiosis

Endosalpingiosis is defined as ectopic tubal epithelium. It usually occurs in the pelvic and abdominal peritoneum and may rarely involve the serosal surface of the vermiform appendix. Cystic endosalpingiosis is usually seen as a multilocular septated cystic mass in imaging studies.

The walls of the cystic mass and septal structure may show contrast enhancement mimicking a tumor. Endosalpingiosis cannot cause pain. The association of acute appendicitis and cystic endosalpingiosis is incidental and it must be considered in the differential diagnosis of cystic appendiceal tumors (Figure 5). It is commonly diagnosed through histological examinations [8].

Figure 5.

Oral and intravenous contrast enhanced coronal reformatted CT image demonstrate cystic endosalpingiosis (curved arrows) with appendicolith (not shown) in the middle part of the inflamed and enlarged appendix in a 30-year-old female patient

Intussusception of the appendix

Intussusception of the appendix is a rare disease that constitutes a diagnostic challenge. It may mimic acute appendicitis, may present with typical symptoms of intussusception, or may be totally asymptomatic. There may be partial invagination to caecum or the whole colon may be involved, and, furthermore, the appendix may be totally or partially inverted with or without a lead point. Physiological and anatomical changes associated with pregnancy may obscure or delay the correct diagnosis of AA. Abdominal ultrasonography has a high rate of non-visualization of the appendix in gravid patients, and CT presents a potential hazard to the developing fetus due to ionizing radiation (Figure 6) [9, 10].

Figure 6.

Coronal reformatted CT image demonstrates a filling defect in the caecum due to appendiceal intussusception and inverted appendix in a 34-year-old female (arrow)

Acute appendicitis with pregnancy

Physiological and anatomical changes associated with pregnancy may obscure or delay the correct diagnosis of AA. Abdominal ultrasonography has a high rate of non-visualisation of the appendix in gravid patients, and CT presents a potential hazard to the developing fetus due to ionizing radiation. However, MR imaging of the appendix is the safe and preferred modality when appendicitis is suspected in pregnant women. MR imaging findings of appendicitis include an appendiceal diameter greater than 7 mm, an appendiceal wall thickness greater than 2 mm, high-signal-intensity luminal contents on T2-weighted images, hyperintense periappendicular fat stranding and fluid, and restricted diffusion in diffusion-weighted image (Figure 7) [11].

Figure 7.

Diffusion-weighted image with b value of 800 s/mm2 shows inflamed appendix with restricted diffusion (arrow) in a 28-year-old female at 7 weeks of gestation (not shown) with right lower quadrant abdominal pain

Rare Clinical Mimics

Anomalous congenital band

Congenital bands of the abdomen are a rare cause of acute abdomen in chidren and extremely rare in adults. Its location is variable and may be found between the bowel/mesentery/abdominal wall/liver and intraabdominal ligaments. The etiology of these bands remains unclear, since its location is not similar to that of remnants. Although they usually cause bowel obstruction symptoms due to compression or entrapment of a bowel, the presentation may suggest mesenteric infarction, perforated duodenal infarction, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, strangulated hernia, and AA. Although it is difficult to establish a preoperative imaging diagnosis, a congenital band should also be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with symptoms and signs of AA in the absence of previous surgery, which excludes postoperative intraabdominal adhesions or bands (Figure 8) [12].

Figure 8. a, b.

Axial CT image after oral and intravenous contrast administration (a) demonstrates a congenital band as a curvilinear irregular structure extending from the anterior abdominal wall to the mesenteric root (arrows). Intraoperative photograph (b) shows the anomalous congenital band as a cause of terminal ileum entrapment

Duplication cysts

Alimentary tract duplication cysts are uncommon congenital anomalies containing a normal gastrointestinal mucosa and smooth muscle layer. Duplications have two types, either cystic or tubular attached to the gastrointestinal tract, and they share the same blood supply. Clinical symptoms may vary depending on their type, site, and size and may include pain, distension, palpable mass, vomiting, and bleeding. They may also present with complications such as perforation, intussusception, bowel obstruction, and volvulus. Duodenal duplication cysts and tubular jejunal duplication cysts, which directly communicate with the bowel lumen, are extremely rare entities causing acute right lower abdominal pain mimicking AA in adults (Figure 9, 10) [13].

Figure 9. a, b.

Duodenal duplication cyst in a 17-year old male with right-sided abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Coronal reformatted CT (a) image demonstrates an oval cystic mass in the second and third portions of the duodenum extending along the medial wall (arrow). MR Cholangiopancreatography (b) demonstrates the intraduodenal cystic mass (star) without any communication with distal common bile duct

Figure 10.

Tubular jejunal duplication cyst in a 19-year-old female with acute abdominal pain and elevated white blood cell count. Postcontrast axial CT image demonstrates a cystic mass arising from the mesenteric aspect of jejunum (arrow)

Meckel’s diverticulitis

A Meckel diverticulum is a vestigial remnant of the omphalomesenteric (vitellointestinal) duct that communicates between the yolk sac and midgut lumen of the developing fetus. Thus, it is a true diverticulum that includes all three coats of the small intestine. It may range from 1 to 12 cm in length and is found at an average distance of 60 cm from the ileo-cecal valve. They may include embryonic remnants such as ectopic gastric mucosa and pancreatic tissue. The inflamed Meckel’s diverticulum is usually seen as a blind-ending pouch of variable size and mural thickness that arises from the antimesenteric side of the distal ileum with surrounding mesenteric inflammation in imaging studies. The location of the diverticulum may vary from the right lower quadrant to the mid abdomen. It may occur with hemorrhagic, mechanical, infectious, or tumoral complications. The diagnosis is most difficult in the setting of secondary intestinal obstruction (Figure 11) [14].

Figure 11. a, b.

Axial oral contrast-enhanced (a) CT image of the abdomen in a 32-year-old man with sudden-onset abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting shows unenhancing circular-shaped blind-ending fluid-filled bowel loop (arrow), suggesting Meckel’s diverticulitis. Intraoperative photograph (b) shows Meckel’s diverticulitis with gangrenous discoloration

Inflammatory fibroid polyp

Inflammatory fibroid tumor or Vanek’s tumor of the ileum may simulate clinical findings of acute appendicitis, but imaging findings easily rule that out. It is a rare benign lesion of the gastrointestinal tract, and the most common location is the antrum of the stomach. Clinical presentation varies by location and size, and an ileal location can present with abdominal pain, lower gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia, and (rarely) small bowel obstruction due to intussusception. Determination of an intraluminal mass between 2 and 5 cm with intussusception and mechanical intestinal obstruction is the key finding for preoperative diagnosis on imaging (Figure 12) [15].

Figure 12. a, b.

A 52-year-old woman with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Contrast-enhanced coronal (a) reformatted CT image shows intraluminal mass (arrow) complicated by intestinal obstruction. Intraoperative photograph (b) shows the inflammatory fibroid tumor (Vanek’s tumor) of the ileum

Spontaneous urinary extravasation

Spontaneous urinary extravasation is defined as a non-traumatic urinary leakage from the collecting system due to an excessive sudden increase in the intraluminal pressure as a result of obstruction and may be together with perirenal and retroperitoneal urinoma formation. It is an uncommon complication of obstructive uropathy and usually results from a stone in the uretero-vesical junction.

Other causes may include extrinsic ureteral compression by tumors, pelviureteric junction obstruction, vesicoureteric junction obstruction, instrumentation, and trauma. Clinical presentation may range from mild flank pain, nausea, and vomiting to acute abdomen, and symptoms may mimic pyelonephritis, duodenal ulcer, biliary colic, cholecystitis, and appendicitis. The most useful imaging modality to identify spontaneous urinary extravasation is abdominal computed tomography. Delayed images usually show extravasation of the contrast medium and provide information regarding the perforation site (Figure 13) [16].

Figure 13. a, b.

Axial delayed phase (a) and unenhanced (b) CT images demonstrate renal pelvis rupture (arrowhead) and urinary extravasation (arrow) due to an opaque calculi in the ureterovesical junction (thick arrow) in a 67-year-old female with acute right-sided abdominal pain without dysuria or hematuria

Renal artery thrombosis and renal infarction

Acute renal infarction due to right renal artery thrombosis is rare and usually present with abrupt flank or abdominal pain accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and fever. The laboratory findings include leukocytosis besides hematuria, proteinuria, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase. The differential diagnosis of the disease is extensive, and emergent surgical or nonsurgical conditions causing acute abdominal pain such as AA should be ruled out [17]. A contrast-enhanced CT is the best way to recognize the disease (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

A 49-year-old female with a history of malignancy and acute right-sided abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen demonstrates right renal artery thrombus (arrow) and infarction of right kidney

OHVIRA Syndrome

Uterus didelphys with obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agenesis (OHVIRA syndrome) is a very uncommon developmental urogenital malformation. It results from complete failure of fusion of the müllerian ducts and their normal differentiation to form a cervix and uterus during the 8th week of gestation. It usually presents after menarche with remittent pelvic pain and a palpable pelvic mass due to hematocolpos. It may present with acute severe abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen [18]. Magnetic resonance imaging is the best imaging modality to confirm the diagnosis and provides excellent images demonstrating iso/high T1W signal and high T2W signal that indicates pelvic fluid collection contiguous with the endocervix along with didelphic uterus and an absent kidney on the affected side (Figure 15).

Figure 15. a, b.

A 42-year-old female patient with right lower quadrant abdominal pain. Axial T2-weighted MR images (a, b) demonstrate a collection with fluid-fluid levels that exhibits low and high signals in the right obstructed vagina referred to hematocolpos (star) and a uterus didelphys (arrow). There is also an absence of the right kidney (not shown)

In conclusion, we have briefly reviewed the imaging appearances of unusual presentations and coexisting pathologies of AA together with its uncommon clinical mimics. In patients with suspected AA, clinicians and radiologists should remain vigilant for rare presentations, associations and mimics in order to make a prompt correct diagnosis and to avoid unnecessary or complicated surgical interventions.

Footnotes

Informed Consent: Informed consent is not necessary due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - M.K.D., Y.S.; Design - M.K.D., Y.S., Y.F.; Supervision - M.K.D.; Resources - M.K.D, Y.S., Y.F., T.C., S.D., B.T., M.A.; Materials - M.K.D, Y.S., Y.F., T.C., S.D., B.T.; Data Collection and/or Processing - M.K.D., Y.S., Y.F., M.A.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - M.K.D..; Literature Search - M.K.D., B.T., M.A.; Writing Manuscript - M.K.D.; Critical Review - M.K.D., Y.S.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Yu J, Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Halvorsen RA. Helical CT evaluation of acute right lower quadrant pain: Part I, Common mimics of appendicitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1136–42. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.4.01841136. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.184.4.01841143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shademan A, Tappouni RF. Pitfalls in CT diagnosis of appendicitis: pictorial essay. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2013;57:329–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2012.02451.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9485.2012.02451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs JE, Balthazar EJ. Diseases of the appendix Textbook of gastrointestinal radiology. 3rd edn. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2008. pp. 1039–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-2332-6.50065-8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deshmukh S, Verde F, Johnson PT, Fishman EK, Macura KJ. Anatomical variants and pathologies of the vermix. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21:543–52. doi: 10.1007/s10140-014-1206-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-014-1206-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horrow MM, White DS, Horrow JC. Differentiation of perforated from nonperforated appendicitis at CT. Radiology. 2003;227:46–51. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272020223. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2272020223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacobellis F, Iadevito I, Romano F, Altiero M, Bhattacharjee B, Scaglione M. Perforated Appendicitis: Assessment With Multidetector Computed Tomography. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2016;37:31–6. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2015.10.002. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sult.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michalinos A, Moris D, Vernadakis S. Amyand’s hernia: a review. Am J Surg. 2014;207:989–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollheimer MJ, Leibl S, Pollheimer VS, Ratschek M, Langner C. Cystic endosalpingiosis of the appendix. Virchows Arch. 2007;450:239–41. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0328-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-006-0328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaar CI, Wexelman B, Zuckerman K, Longo W. Intussusception of the appendix: comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Surg. 2009;198:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.08.023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hines JJ, Paek GK, Lee P, Wu L, Katz DS. Beyond appendicitis; radiologic review of unusual and rare pathology of the appendix. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2016;41:568–81. doi: 10.1007/s00261-015-0600-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-015-0600-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ditkofsky NG, Singh A. Challenges in Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Suspected Acute Appendicitis in Pregnant Patients. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2015;44:297–302. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2015.01.001. https://doi.org/10.1067/j.cpradiol.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeda A, Yokoi S, Kunou T, et al. Intestinal obstruction in the terminal ileum caused by an anomalous congenital vascular band between the mesoappendix and the mesentery: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:793–795. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2821-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-004-2821-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee NK, Kim S, Jeon TY, et al. Complications of congenital and developmental abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract in adolescents and adults: evaluation with multimodality imaging. Radiographics. 2010;30:1489–507. doi: 10.1148/rg.306105504. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.306105504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotha VK, Khandelwal A, Saboo SS, et al. Radiologist’s perspective for the Meckel’s diverticulum and its complications. Br J Radiol. 2014;87:20130743. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130743. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20130743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldis M, Dilly M, Marty M, Laurent F, Cassinotto C. An inflammatory fibroid polyp responsible for an ileal intussusception discovered on an MRI. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2014.01.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen GH, Hsiao PJ, Chang YH, et al. Spontaneous ureteral rupture and review of the literature. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:772–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.03.034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amilineni V, Lackner DF, Morse WS, Srinivas N. Contrast-enhanced CT for acute flank pain caused by acute renal artery occlusion. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:105–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.1.1740105. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.174.1.1740105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karaca L, Pirimoglu B, Bayraktutan U, Ogul H, Oral A, Kantarci M. Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich syndrome: a very rare urogenital anomaly in a teenage girl. J Emerg Med. 2015;48:e73–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.09.064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]