Abstract

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Financial Alignment Initiative represents the largest effort to date to move beneficiaries who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid—known as dual eligibles—into a coordinated care model by the use of passive (automatic) enrollment. Thirteen states are testing integrated payment and delivery demonstration programs in which an estimated 1.3 million dual eligibles are qualified to participate. As of October 2016, passive enrollment had brought over 300,000 dual eligibles into nine capitated programs in eight states. However, program participation levels remained relatively low. Across the eight states, only 26.7 percent of dual eligibles who were qualified to participate were enrolled, ranging from 5.3 percent for the two New York programs together to 62.4 percent in Ohio. Although the exact causes of the high rates of opting out and disenrolling that we observed among passively enrolled dual eligibles are unknown, experience to date suggests that administrative challenges were combined with demand- and supply-side barriers to enrollment. These early findings draw into question whether passive enrollment can encourage dual eligibles to participate in integrated care models.

More than 10.7 million people in the United States are dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid coverage.1 They qualify for Medicaid as a result of their low incomes and limited assets. Roughly two-thirds of these dual eligibles are elderly people who meet the age requirement for Medicare, while the remaining third qualify for Medicare through the Social Security Disability Insurance program. The population of dual eligibles includes some of the sickest, frailest, and most vulnerable people covered by either program. Dual eligibles are more likely than other Medicare beneficiaries to have multiple chronic conditions, functional limitations so that they require assistance with activities of daily living, and a serious mental illness or substance use disorder.2

Medicare spends twice as much per dual eligible as it does per Medicare-only beneficiary.3 Much of this spending reflects the poor health of the dual eligibles, but it is also affected by the fact that Medicare and Medicaid sometimes work at cross purposes, given the fragmented nature of their coverage.4 Medicare covers acute care services for them (including hospital procedures, physician visits, prescription drugs, and postacute care), while Medicaid covers long-term care services and Medicare premiums and cost-sharing obligations.5 Medicare and Medicaid are large public programs with frequently misaligned incentives that can discourage care coordination, which results in reduced quality of care and increased spending.4 The Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services (CMS) recently concluded: “Enrollees could benefit from more integrated systems of care that meet all of their needs—primary, acute, long-term, behavioral, and social—in a high quality, cost-effective manner. Better alignment of the administrative, regulatory, statutory, and financial aspects of these two programs holds promise for improving the quality and cost of care for this complex population.”1(p3) Importantly, integration entails not just financial alignment across Medicare and Medicaid but also coordination in the delivery of services.6

Historically, very few dual eligibles have received care under an integrated Medicare-Medicaid program.7 Federal and state programs that attempted integration included the federal Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly and state programs such as Minnesota Senior Health Options, Massachusetts’s Senior Care Options, and the Wisconsin Partnership Program. A more recent effort is the Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans (SNPs) oriented toward dual eligibles—an effort that continues to evolve toward meaningful integration in terms of financial alignment or care delivery.6

A key issue that plagued all of these efforts to coordinate care for dual eligibles was low voluntary program enrollment and favorable selection in which only lower-cost (after risk adjustment) dual eligibles enrolled.4 For example, by the end of 2014, the Medicare Advantage SNPs had enrolled only about 1.2 million of the 10.7 million dual eligibles who could have participated.8

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), CMS launched the Financial Alignment Initiative in 2011 to address the fragmentation between Medicare and Medicaid and to integrate the delivery of primary, acute, behavioral health, and long-term care services for dual eligibles. To date, CMS has entered into fourteen memoranda of understanding with thirteen states to test new integrated payment and delivery models, in which an estimated 1.3 million dual eligibles would qualify for enrollment—although it is unclear whether states have attempted to enroll all of these individuals.8

To encourage broader enrollment among dual eligibles, many of the state programs use a passive (that is, automatic) enrollment approach, which means that dual eligibles have to choose to opt out of the program, instead of having to opt in to it. CMS anticipated that between one and two million dual eligibles would participate8 and capped the number of program participants across all states at two million.9 In a CMS evaluation of initial enrollment in six of the demonstration programs (in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, Ohio, Virginia, and Washington), fewer dual eligibles enrolled in the first six months of operations than the states had originally anticipated.10 Similar independent evaluations by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC)8 and the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation11 have suggested lower than expected enrollment.

Passive enrollment is frequently used in state Medicaid programs to assign enrollees who do not make a choice to a managed care plan, but its use in Medicare has been less frequent.8 Medicare passively enrolls dual eligibles into Medicare Part D plans and Medicare Advantage SNPs. For example, thirteen states with mature Medicaid managed care plans were given a onetime opportunity in 2006 to passively enroll dual eligibles into their companion Medicare Advantage SNPs.12 An estimated 213,000 dual eligibles in managed Medicaid long-term care plans were passively enrolled in a Medicare Advantage SNP through this process.8 The Financial Alignment Initiative represents the largest effort to date to passively enroll dual eligibles in managed care.

After a brief review of the state programs, we examine early enrollment in this important demonstration project and then discuss its implications for the future of the programs.

Background On State Programs

Initially, thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia submitted letters of intent to participate in the Financial Alignment Initiative; twenty-six states ultimately submitted a proposal. However, a number of states subsequently withdrew—citing concerns about the payment methodology, rate setting mechanisms, carve-out allowances, and limited health plan interest.13 Fourteen programs in thirteen states are currently active. CMS does not expect to approve any additional state demonstration programs.8

Of the fourteen demonstration programs, eleven (in ten states) use a capitated model of financial alignment. The capitated state programs (with their first date of enrollment in parentheses) are in California (April 2014), Illinois (March 2014), Massachusetts (October 2013), Michigan (March 2015), New York (one program in January 2015, the other in April 2016), Ohio (May 2014), Rhode Island (May 2016), South Carolina (February 2015), Texas (March 2015), and Virginia (April 2014).14 Demonstration programs in Colorado (September 2014) and Washington (July 2013) use a managed fee-for-service financial alignment model. The program in Minnesota (September 2013) uses an administrative alignment model, building on the long-standing Minnesota Senior Health Options program for coordinating care for the dual eligibles.

Colorado, Minnesota, Rhode Island, and South Carolina have statewide programs encompassing all dual eligibles, whereas the other ten state programs are limited to particular geographic regions or counties.14 Some states also target particular subpopulations of dual eligibles. For example, Massachusetts includes only nonelderly dual eligibles with disabilities, Minnesota targets elderly dual eligibles, and South Carolina targets elderly dual eligibles who live in the community at enrollment.14

In almost every capitated state program, the demonstration began with a period of voluntary enrollment in which the dual eligible had to opt in to the program. After this initial period, the program switched to passive enrollment: Dual eligibles then either opted out of the program or were automatically assigned to a managed care plan. According to CMS rules, to implement passive enrollment, at least two plans must be available to beneficiaries. States are using a range of “intelligent assignment” algorithms to place dual eligibles in plans. For example, Massachusetts and California match dual eligibles to a plan based on their most frequently used physician to minimize the likelihood that they will have to switch physicians.14

Study Data And Methods

Data Sources

Enrollment figures for the state integrated care demonstration programs were obtained from the CMS total monthly enrollment reports for Medicare Advantage (MA) plan enrollment. We included in our analysis only those plans labeled as “Medicare–Medicaid HMO [health maintenance organization]” or “Medicare–Medicaid HMO–POS [health maintenance organization–point of service plan].” The data were organized by month, state, county, and plan. The earliest enrollment in an integrated capitated dual-eligibles plan was October 2013 in Massachusetts. We had data through October 2016. We excluded the South Carolina and Rhode Island programs because they were recently implemented at the time of our analysis. Thus, we focused on the other nine capitated programs in eight states.

The dates at which each of the states began active and passive enrollment in their programs were obtained from multiple sources. CMS provides a list of key dates, including the start of active and passive enrollment, on its Medicaid-Medicare Coordination website. However, the listed dates reflect the initial anticipated dates and might not be accurate in cases where enrollment was pushed back or staggered. Thus, we used the most recent documentation of enrollment dates, when available. We also obtained estimates of the total number of dual eligibles who could participate in each of the programs from a recent MedPAC report.8

Measures

The primary variable of interest was the number of dual eligibles enrolled in each state’s integrated plan during the active and passive enrollment phases. Because data were reported as the total number of dual eligibles enrolled in a given month, we report the total number enrolled in the last month of the active enrollment period. Thus, for example, when reporting the number of dual eligibles enrolled during active enrollment in Ohio, we report the number enrolled in December 2014, which was the last month before the start of passive enrollment. We give the total number of participating health plans in operation in each state. We identified unique plans by their organization name within the state, noting that one plan could have multiple contracts. We compared these enrollment figures and the total number of dual eligibles who could participate in the programs, as reported to CMS by the states.8

Analyses

We examined the total number of dual eligibles enrolled in the plans during active and passive enrollment periods. We first present data at the level of the state before examining monthly enrollment trends in three representative states—California, Massachusetts, and Ohio. We selected these three states because Ohio had one-time statewide passive enrollment, Massachusetts had multiple statewide passive enrollment periods, and California used passive enrollment for different markets at different times.

Limitations

Our analysis was limited in several ways. First, we had data for only eight states with capitated programs. The CMS website did not contain data on the two managed fee-for-service programs, those in Colorado and Washington. A CMS report suggested that program enrollment in Washington at six months was quite low and mirrored initial enrollment in the capitated states.10 The Minnesota program uses an administrative alignment model, and we did not have enrollment data for that program. Given these differences, our results for the capitated programs were not generalizable to these other state programs or programs in states that did not participate in the demonstration.

Second, we had data only on the numbers of dual eligibles enrolled in the programs in each month—numbers that take into account both new enrollment and disenrollment by existing plan members in each month. Thus, we could not calculate the number of new enrollees in each period.

Third, we did not have data on the demographic characteristics or previous health care utilization for the dual eligibles who enrolled (or for those who did not enroll) in the programs. As a result, we were not able to analyze whether the programs experienced differential selection.

Finally, we did not have access to the underlying reasons why dual eligibles chose to participate (or not to participate) in the programs. We speculate on some reasons below, but future qualitative research will be necessary to identify some of the mechanisms underlying our findings.

Study Results

We studied the impact of passive enrollment on program uptake across eight states that collectively had over 1.2 million dual eligibles who qualified for participation in the demonstration programs (Exhibit 1). The demonstrations varied considerably in their overall design, but all of them used passive enrollment at different points in time following a period of active enrollment. During the active enrollment period, relatively few dual eligibles enrolled in the programs. Indeed, across all eight states, only 22,818 individuals were enrolled at the close of the active enrollment period. In October 2016 this number represented only 7.0 percent of total program enrollment.

Exhibit 1.

Numbers of enrollees in eight capitated state programs under the CMS Financial Alignment Initiative

| Passive enrollment

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Active enrollment | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | Eligible enrollees | Enrollees | Participating plans |

| CA | 350 | 98,380 | —a | —a | 424,000 | 23.2% | 11 |

| IL | 2,544 | 44,717 | —a | —a | 154,000 | 29.0 | 7 |

| MA | 3,988 | 9,348 | 13,187 | 13,534 | 101,000 | 13.4 | 2 |

| MI | 686 | 37,548 | —a | —a | 105,000 | 35.8 | 7 |

| NYb | 539 | 5,258 | —a | —a | 100,000 | 5.3 | 16 |

| OH | 14,457 | 58,050 | —a | —a | 93,000 | 62.4 | 5 |

| TX | 20 | 37,251 | —a | —a | 165,000 | 22.7 | 5 |

| VA | 234 | 1,763 | 28,473 | —a | 67,000 | 42.5 | 3 |

| All | 22,818 | —a | —a | 323,481c | 1,209,000 | 26.7 | 56 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data on Medicare Advantage plan enrollment from the total monthly enrollment reports of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

NOTES Numbers of eligible enrollees were obtained from Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system (Note 8 in text). Numbers of active and passive enrollees were measured in the last month of the active or passive enrollment period.

Not applicable.

The New York enrollment figures include the two demonstration programs in the state.

Current enrollment across all eight states as of October 2016.

Program participation increased during the passive enrollment period. Across all eight states, the enrolled population increased to 323,481 by October 2016. Passive enrollment was the main driver of program uptake, accounting for over 300,000 new enrollees. However, in spite of passive enrollment, the majority of dual eligibles who could participate were still not enrolled in the programs. Specifically, across all eight states, only 26.7 percent of dual eligibles who could participate were enrolled in October 2016, ranging from 5.3 percent in the two New York programs combined to 62.4 percent in Ohio. Massachusetts was the first program to begin accepting enrollees, in October 2013, yet only 13.4 percent of dual eligibles who could participate were enrolled in October 2016.

The states varied in the number of plans participating in the program. Across all eight states, fifty-six plans were in operation as of October 2016, ranging from a low of two plans in Massachusetts to a high of sixteen plans in New York (Exhibit 1). Seven plans had left the program since the beginning of the demonstration. Five of these plans were in New York, one in Massachusetts, and one in Illinois.

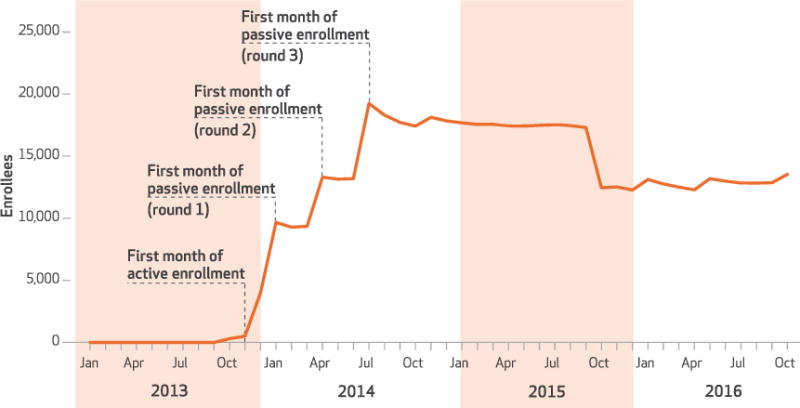

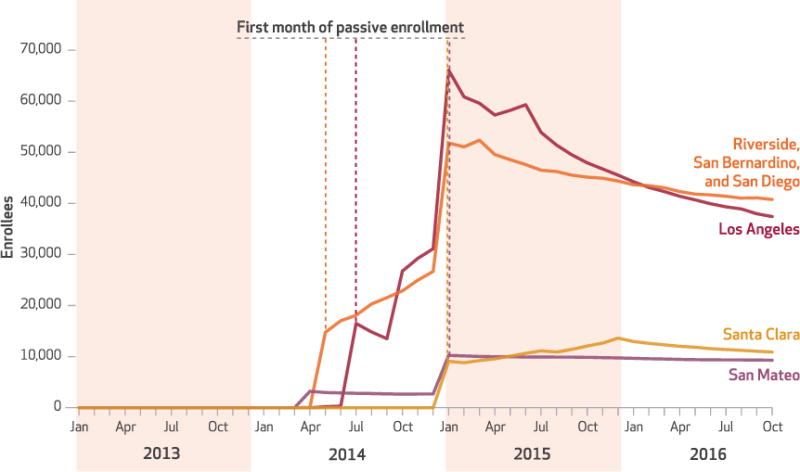

Ohio exhibited a large one-time increase in enrollment around its first month of passive enrollment, January 2015 (Exhibit 2). Massachusetts had three different rounds of passive enrollment, each of which was associated with large increases in enrollment (Exhibit 3). California implemented passive enrollment in different counties at different times (Exhibit 4). Each county experienced large relative increases in plan uptake at the beginning of its period of passive enrollment.

Exhibit 2. Number of enrollees in the Ohio Financial Alignment Initiative demonstration, by month, 2013–16.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data on Medicare Advantage plan enrollment from the total monthly enrollment reports of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Exhibit 3. Number of enrollees in the Massachusetts Financial Alignment Initiative demonstration, by month, 2013–16.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data on Medicare Advantage plan enrollment from the total monthly enrollment reports of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Exhibit 4. Number of enrollees in the California Financial Alignment Initiative demonstration, by month, 2013–16.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data on Medicare Advantage plan enrollment from the total monthly enrollment reports of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

NOTE All counties began active enrollment in April 2014 except San Mateo, which began passive enrollment in that month.

In each of these three states, program enrollment declined after the initial increase that was due to passive enrollment. For example, the Ohio program had 68,699 dual eligibles enrolled in the first month of passive enrollment (January 2015), but this number fell to 56,889 in July 2016, before rising again slightly to 58,050 in October 2016. Similarly, enrollment in the Massachusetts program peaked at 19,242 dual eligibles in July 2014, around the third round of passive enrollment, but it declined 36 percent to 12,287 in April 2016, before rising slightly to 13,354 in October 2016. In California overall statewide enrollment declined since passive enrollment was first implemented, but the experience differed across the four program areas. In Los Angeles, enrollment peaked at 66,096 dual eligibles in January 2015 but declined 43 percent to 37,416 in October 2016. In the Riverside–San Bernardino–San Diego market, enrollment reached 52,356 dual eligibles in March 2015 and declined 22 percent to 40,771 in October 2016. Enrollment in the San Mateo market reached 10,245 dual eligibles in January 2015 and declined 9 percent to 9,294 in October 2016. Finally, in the Santa Clara market, enrollment reached a peak of 13,622 in December 2015 before declining 20 percent to 10,899 in October 2016.

Discussion

CMS anticipated enrolling between one and two million dual eligibles in the Financial Alignment Initiative across all the participating states.8 Overall participation fell far below this number, in spite of the use of passive enrollment. Passive enrollment brought only 300,000 dual eligibles into the demonstration programs, with the majority of dual eligibles in these states who could participate not yet enrolled in the programs. Across the eight state programs analyzed in this study, 26.7 percent of dual eligibles who could participate were enrolled as of October 2016, ranging from 5.3 percent in New York to 62.4 percent in Ohio. We next discuss the implications of these findings for the future of the programs.

Why Hasn’t Passive Enrollment Met Expectations?

Here we discuss three potential sets of explanations for the low program uptake under passive enrollment: administrative and design challenges, demand-side factors, and supply-side factors.

ADMINISTRATIVE AND DESIGN CHALLENGES

Passive enrollment has faced a number of administrative challenges under the Financial Alignment Initiative. The lack of good contact information for some dual eligibles has contributed to low enrollment in certain states.10 Some dual eligibles might have been excluded from the program for other administrative reasons, which suggests that the eligible population might have been smaller than anticipated. It will be important to examine this issue of program eligibility using data on the number of beneficiaries who actively opt out of the demonstrations in the different states.15 Moreover, although states have tried to use Medicare claims data to “intelligently” assign dual eligibles to plans so that they could keep their current physician, stakeholders have indicated that this assignment process has not always worked well.8 States have also been criticized for their poor outreach to and education of dual eligibles and providers regarding passive enrollment.8 Similarly, participants in the programs have reported that the materials they received before and after enrollment were not clear or written in language they could easily understand.16

MedPAC contrasted the experience in Ohio, whose program had the highest rate of participation (62.4 percent), with that in New York, whose two programs collectively had the lowest rate of participation (5.3 percent).8 The high participation rate in Ohio partly stemmed from the program’s two-stage enrollment process. In the first stage (May 2014), the state required all dual eligibles who qualified to move into a managed care plan for their Medicaid benefits. In the second stage (January 2015), the state passively enrolled these dual eligibles into companion Medicare plans offered by the same parent company. In New York, the state placed very stringent requirements for care coordination on plans, including the requirement that the enrollee participate in care plan meetings. Med-PAC reported that over 61,000 dual eligibles had opted out of the program.8

The lesson from these two states is that a multistage and less restrictive passive enrollment process might ultimately prove more effective than a single-stage and more restrictive process in keeping dual eligibles in an integrated care model. However, a more restrictive enrollment process might allow state programs to target people who are most likely to generate savings. For example, the beneficiaries who were excluded in New York because of their unwillingness to participate in care plan meetings might also have been unlikely to cooperate with efforts to reduce unnecessary utilization and expenditures.

DEMAND-SIDE FACTORS

A straightforward explanation for low program uptake is that—even in the context of passive enrollment—some dual eligibles have concluded that the risks and uncertainty of enrolling in the demonstration outweigh the potential benefits of improved coordination. Policy makers and researchers have outlined the potential for improved care coordination under these programs, and some states have added supplementary benefits relative to traditional coverage.1,10,17 But at the end of the day, dual eligibles may not see the upside to changing their insurance coverage. Indeed, even among those dual eligibles who were initially passively enrolled in the programs, we observed disenrollment as they moved back to their traditional coverage. The high rates of opting out and disenrollment suggest that dual eligibles may be much more alert to changes in their insurance coverage than originally anticipated.

The exact reasons for the high numbers of people opting out and disenrolling are unclear, but previous research on active choices in integrated care programs suggests that disenrollment may be partially explained by concerns among dual eligibles that they will have to change doctors, go to new locations for care, and have fewer choices.18 States reported to CMS that dual eligibles have opted out of the demonstration programs for several reasons, including satisfaction with their traditional care, providers not having contracted with plans in the demonstrations, general confusion about the demonstrations, and providers encouraging dual eligibles not to enroll.10 Indeed, in the California program, the opt-out rate has been particularly high in the Los Angeles market, with reports of providers encouraging dual eligibles to opt out to maintain their Medicare fee-for-service coverage.19

SUPPLY-SIDE FACTORS

Another explanation for low enrollment is related to the potential inadequacy of the capitation rates paid to the plans to cover dual eligibles. Low payments stemmed from two factors. First, CMS and the states took out the expected savings before setting the capitation rates. Second, CMS set the budgets in the capitated demonstration programs based on the risk-adjustment methods used to set capitation rates for dual eligibles in Medicare Advantage, which has historically underpaid plans for the care of dual eligibles. CMS increased payment rates in 2016 for most plans by 5–10 percent for the Part A and Part B components because the rates had been found to be too low. In some states, it has been reported that fewer plans than expected have participated in the demonstrations, limiting program capacity and the ability of states to implement passive enrollment—which requires that at least two plans be available to each beneficiary.10 Low payment rates may also have led to targeted outreach by the plans to attract enrollees who were relatively low cost and thus more profitable than others.

Lessons Learned

The federal government is studying the different state demonstration programs to evaluate whether these models can lower costs and improve outcomes for dual eligibles. The most significant limitation of previous evaluations of integrated care programs for dual eligibles has been the failure to incorporate a randomized study design or an appropriate statistical correction (such as instrumental variables) to address the issue of selection bias across the treatment and comparison groups.20 Unobserved factors may differ across the treatment and control groups and bias comparisons of costs and outcomes. For example, the voluntary Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly was found to have experienced favorable selection in that relatively healthy dual eligibles enrolled in the program.21 Passive enrollment was thought to be a mechanism that would expand the risk pool. Indeed, previous research has even used passive enrollment as a way to address risk selection in comparisons of Medicaid managed care plans.22 However, the high opt-out rate that we found brings this premise into question, thereby threatening the internal validity of any evaluation of costs and health outcomes.

Mandatory Enrollment

If policy makers want to increase enrollment in integrated care programs, CMS may need to go beyond passive enrollment by making enrollment mandatory. However, Medicare freedom of choice provides beneficiaries with the statutory right to choose between a managed Medicare program and traditional fee-for-service Medicare. It is unclear whether it is politically feasible to change the rules so that dual eligibles are required to enroll in integrated plans. Indeed, CMS has been reluctant even to use “lock-in periods” that limit when dual eligibles can disenroll from the demonstrations.8

Another potential mechanism for expanding the number of enrollees in integrated care programs would be to increase the financial incentives for plans and dual eligibles to participate in these programs. However, this might make it more difficult to offer dual eligibles a product that is cost-effective relative to traditional coverage.

Conclusion

The Financial Alignment Initiative demonstration was implemented with the goal of improving the coordination of Medicare and Medicaid services for dual eligibles. Although passive enrollment has brought over 300,000 dual eligibles into the demonstration programs, the majority of dual eligibles who qualified for participation in them remained unenrolled. ■

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number P01 AG032952.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

David C. Grabowski, Professor in the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, in Boston, Massachusetts

Nina R. Joyce, Postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School

Thomas G. McGuire, Professor of health economics in the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School

Richard G. Frank, Margaret T. Morris Professor of Health Economics in the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School

NOTES

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office fiscal year 2015 report to Congress [Internet] Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2017 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-Office/Downloads/MMCO_2015_RTC.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Congressional Budget Office. Dual-eligible beneficiaries of Medicare and Medicaid: characteristics, health care spending, and evolving policies [Internet] Washington (DC): CBO; 2013. Jun, [cited 2017 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/44308_DualEligibles2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Data book: beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid [Internet] Washington (DC): Med-PAC; 2015. Jan, [cited 2017 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/2015-Dually-Eligible-Beneficiaries-Data-Book.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grabowski DC. Medicare and Medicaid: conflicting incentives for long-term care. Milbank Q. 2007;85(4):579–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henry J, Kaiser Family Foundation . The diversity of dual eligible beneficiaries: an examination of services and spending for people eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): KFF; 2012. Apr 1, [cited 2017 Feb 24]. Available from: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7895–02.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grabowski DC. Special Needs Plans and the coordination of benefits and services for dual eligibles. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):136–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold MR, Jacobson GA, Garfield RL. There is little experience and limited data to support policy making on integrated care for dual eligibles. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(6):1176–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system [Internet] Washington (DC): MedPAC; 2016. Jun, [cited 2017 Feb 24]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/june-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Explaining the state integrated care and financial alignment demonstrations for dual eligible beneficiaries [Internet] Washington (DC): The Commission; 2012. Oct, [cited 2017 Feb 27]. (Policy Brief). Available from: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8368.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh EG, (RTI International; Waltham, MA) Report on early implementation of demonstrations under the Financial Alignment Initiative [Internet] Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2015. Oct 25, [cited 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-Office/FinancialAlignmentInitiative/Downloads/MultistateIssueBriefFAI.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barry C, Riedel L, Busch A, Huskamp H. Early insights from One Care: Massachusetts’ demonstration to integrate care and align financing for dual eligible beneficiaries [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2015. May, [cited 2017 Feb 27]. (Issue Brief). Available from: http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-early-insights-from-one-care-massachusetts-demonstration-to-integrate-care-and-align-financing-for-dual-eligible-beneficiaries. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saucier P, Burwell B. The impact of Medicare Special Needs Plans on state procurement strategies for dually eligible beneficiaries in long-term care: final report [Internet] Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2007. Jan, [cited 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.nhpg.org/media/5962/medicaid_contracting.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office fiscal year 2015 report to Congress [Internet] Washington (DC): MACPAC; 2016. Jul 11, [cited 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/MACPAC-Comment-Letter-MMCO-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musumeci M. Financial and administrative alignment demonstrations for dual eligible beneficiaries compared: states with memoranda of understanding approved by CMS [Internet] Washington (DC): Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2015. Dec, [cited 2017 Feb 27]. (Issue Brief). Available from: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/8426-07-financial-alignment-demonstrations-for-dual-eligible-beneficiaries-compared-dec-2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Financial Alignment Initiative for beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare [Internet] Washington (DC): MACPAC; 2016. Jul, [cited 2017 Feb 27]. (Issue Brief). Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Financial-Alignment-Initiative-for-Beneficiaries-Dually-Eligible-for-Medicaid-and-Medicare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.PerryUndem Research/Communications. Experiences with Financial Alignment Initiative demonstration projects in three states: feedback from enrollees in California, Massachusetts, and Ohio [Internet] Washington (DC): Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission; 2015. May, [cited 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Experiences-with-Financial-Alignment-Initiative-demonstrations-in-three-states.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldfeld KS, Grabowski DC, Caudry DJ, Mitchell SL. Health insurance status and the care of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2047–53. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters CP. Medicare Advantage SNPs: a new opportunity for integrated care? Issue Brief George Wash Univ Natl Health Policy Forum. 2005;(808):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorn D. What’s behind high opt-out rate among dual eligibles in L.A. County? California Healthline [blog on the Internet] 2014 Dec 4; [cited 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: http://californiahealthline.org/news/whats-behind-high-optout-rate-among-duals-in-los-angeles-county/

- 20.Grabowski DC. The cost-effectiveness of noninstitutional long-term care services: review and synthesis of the most recent evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(1):3–28. doi: 10.1177/1077558705283120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irvin CV, Massey S, Dorsey T. Determinants of enrollment among applicants to PACE. Health Care Financ Rev. 1997;19(2):135–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace J. How do provider networks impact health and health care? Evidence from random assignment to Medicaid HMOs. 2015 Unpublished paper. [Google Scholar]