Abstract

Endothelial cell insulin resistance may be partially responsible for the higher risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in populations with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). A genome-wide association study revealed a significant association between the ATPase plasma membrane Ca2+ transporting 1 (ATP2B1) gene and T2DM in two community-based cohorts from the Korea Association Resource Project. However, little is known about the implication of the ATP2B1 gene on T2DM. In the present study, we investigated the role of the ATP2B1 gene in endothelial cell insulin sensitivity. ATP2B1 gene silencing resulted in enhanced intracellular calcium concentrations and increased insulin-induced Akt activation compared to that in the negative siRNA-transfected HUVECs (Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells). The elevated insulin sensitivity mediated by ATP2B1 gene silencing was Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent, as verified by administration of the calcium chelator BAPTA-AM or the calmodulin-specific antagonist W7. Moreover, higher levels of phosphorylation of eNOS (Ser1177) were observed in ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs. In addition to BAPTA-AM and W7, L-NAME, an eNOS antagonist, abolished insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 in both si-Neg and si-ATP2B1-transfected endothelial cells. These results indicate that the enhanced insulin sensitivity in ATP2B1-silenced endothelial cells is alternatively dependent on an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and the subsequent activation of the Ca2+/calmodulin/eNOS/Akt signaling pathway. In summary, ATP2B1 gene silencing increased insulin sensitivity in endothelial cells by directly modulating the Ca2+/calmodulin signaling pathway and via the Ca2+/calmodulin/eNOS/Akt signaling pathway alternatively.

Keywords: ATPase plasma membrane Ca2+ transporting 1, Plasma Membrane Calcium ATPase 1, Endothelial Insulin Resistance, Calcium, Calmodulin.

Introduction

Insulin, a peptide hormone secreted by islet β cells, plays a well-defined role in regulating endothelial cell function. There are at least two major pathways to mediate the signaling of insulin in endothelial cells. The activation of the IR/IRS/PI3K/Akt (Insulin Receptor/Insulin Receptor Substrate/Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Protein kinase B) signaling pathway leads to the phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) at Ser1177 and subsequent nitric oxide (NO) production 1. NO is a versatile factor and plays anti-inflammatory, antioxidative stress, antiatherogenic and, importantly, vascular relaxation regulatory roles 1, 2. An IRS-independent SOS/Grb/MAPK/Erk (Son of Sevenless Homolog/Growth Factor Receptor-Bound Protein/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase/Extracellular Regulated Protein Kinase) signaling pathway is also involved in mediating insulin signaling during the regulation of mitogenic action and the expression of proatherogenic endothelin 1 (ET1) and Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) 3-5. Insulin resistance in endothelial cells, characterized by selective inhibition of the IR/IRS/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, has been reported to be associated with the conditions of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) 2, 6. In addition, it may partially be responsible for the higher risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in populations with insulin resistance and T2DM 2, 7. Moreover, supporting evidence from rodent experiments shows that selective insulin resistance plays an important role in the development of atherosclerosis 8-10.

Accumulating evidence shows that there is strong association between SNPs related to ATPase plasma membrane Ca2+ transporting 1 (ATP2B1) gene and hypertension in different ethnic groups, such as European 11, Korean 12, Japanese 13, and Chinese 14. In experimental studies, higher blood pressure was observed in ATP2B1 siRNA-treated mice 15, systemic heterozygous ATP2B1-null mice 16, and vascular smooth muscle cell-targeted ATP2B1 gene KO mice 17. Additionally, impaired NO production may be one of the mechanisms involved in ATP2B1 gene knockdown-induced hypertension 16. Moreover, a genome-wide association study revealed that rs17249754, a SNP located in the intron region of the ATP2B1 gene, was significantly associated with T2DM in two community-based cohorts from the Korea Association Resource Project 18. However, we know little about the implication of the ATP2B1 gene on T2DM.

The ATP2B1 gene, located on chromosome 12q21.33, encodes Plasma Membrane Calcium ATPase 1 (PMCA1)19. In addition, it is well known that PMCA1 protein plays a crucial role in the maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis by ejecting Ca2+ ions from the cytosol 20. Knockdown of the ATP2B1 gene results in higher intracellular Ca2+ concentration 16. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that increased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations are responsible for insulin-induced Akt activation 21. Therefore, we hypothesized that the dysregulation of the ATP2B1 gene expression could regulate endothelial cell insulin sensitivity through modifying intracellular Ca2+ concentration and the Ca2+-associated signaling pathway.

Thus, the current study was designed to examine the effects of silencing ATP2B1 gene expression on intracellular Ca2+ concentration in endothelial cells and to explore how silencing of the ATP2B1 gene modifies insulin sensitivity through the Ca2+-associated cell signaling pathway. Furthermore, we investigated whether the Ca2+-associated activation of eNOS is involved in influencing insulin sensitivity of ATP2B1 gene-silenced HUVECs.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HUVECs (ScienCell Research Laboratories, CA, USA) were cultured in Endothelial cell medium (ECM) (ScienCell Research Laboratories, CA, USA) supplemented with 1× endothelial cell growth supplement (ScienCell Research Laboratories, CA, USA), 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 5% FBS (ScienCell Research Laboratories, CA, USA) in a 37 oC, 5% CO2 incubator. HUVECs were transfected with 100 nM negative-siRNA (Si-Neg) or ATP2B1-siRNA (Si-ATP2B1). The ATP2B1 siRNA for homo sapiens, consisting of 3 target-specific 19-25 nt siRNAs designed to knock down ATP2B1 gene expression, was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA. Catalog Number: sc-42596)

Measurement of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration

The concentration of Ca2+ was measured using Fluo-3-acetoxymethyl ester (fluo-3/AM) according to the protocol described by Mima S et al. with slight modifications 22. Briefly, 48 h after transfection HUVECs were harvested and washed with HANKS buffer with calcium, and then suspended in serum-free low-glucose DMEM with 5 μmol/L fluo-3/AM, 0.1% BSA, 0.04% Pluronic F127, and 2 mmol/L probenecid for 30 min at 37oC. After washing twice with HANKS buffer with calcium, the cells were suspended in assay buffer containing 2 mmol/L probenecid and transferred to a 96-well black plate. The fluorescence signals from cells were measured with a spectrofluorophotometer by recording the excitation signals at 490 nm and the emission signal at 530 nm. Maximum and minimum fluorescence values (Fmax and Fmin) were detected by adding the calcium inopore A23187 or A23187 plus 5 mmol/L EGTA (in Ca2+-free medium), respectively. [Ca2+]i was calculated according to the following equation: [Ca2+]i =Kd (F-Fmin) / (Fmax-F), where Kd is the apparent dissociation constant (400 nmol/L) of the fluorescence dye-Ca2+ complex.

Western blotting

To analyze the levels of phosphor-Akt (Ser 473) and phosphor-eNOS (Ser 1177), the siRNA-transfeced HUVECs were starved of serum overnight followed by pretreatment with or without 30 μM W7 for 30 min, 10 μM BAPTA-AM for 90 min or 50 μM L-NAME for 2 hours respectively. Then, the HUVECs were stimulated with 100 nM insulin for 30 minutes. HUVECs lysates were prepared in 150 μl of lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) on ice in 1.5 ml microtubes for 15 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 g at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and protein concentrations were measured using the Thermo Scientific Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, USA), and then the protein samples were stored at -80℃ until further examination.

For the Western blotting, cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting was performed using specific antibodies against eNOS (1:800)(Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Taxes, USA), phosphor-eNOS (Ser 1177) (1:800) (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Boston, USA), PMCA1 (1:600) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Taxes, USA), Akt (1:1000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Boston, USA), phosphor-Akt (Ser 473) (1:2000) (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Boston, USA) and GAPDH (1:5000) (ZSGB-Bio, Inc., Beijing, China).

Co-immunoprecipitation

For the co-immunoprecipitation experiment, the siRNA-transfected HUVECs were stimulated with 100 nM insulin after overnight serum starvation. HUVECs were lysed in RIPA buffer for IP (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). After the lysates were precleared with protein A/G agarose beads (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), they were incubated with specific antibodies against calmodulin (1:50) (Bioworld Technology, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) overnight at 4°C. Then, the protein A/G agarose beads were added and incubated for 2 h. The supernatants were discarded. After washing with RIPA for IP 3 times, 2× SDS loading buffer were added to the protein A/G agarose beads. The levels of Akt, that co-immunoprecipitated with the antibody against calmodulin, were analyzed by Western blotting.

Statistics

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD from 3-6 separate experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Silencing of the ATP2B1 gene in HUVECs results in increased levels of insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt at serine 473

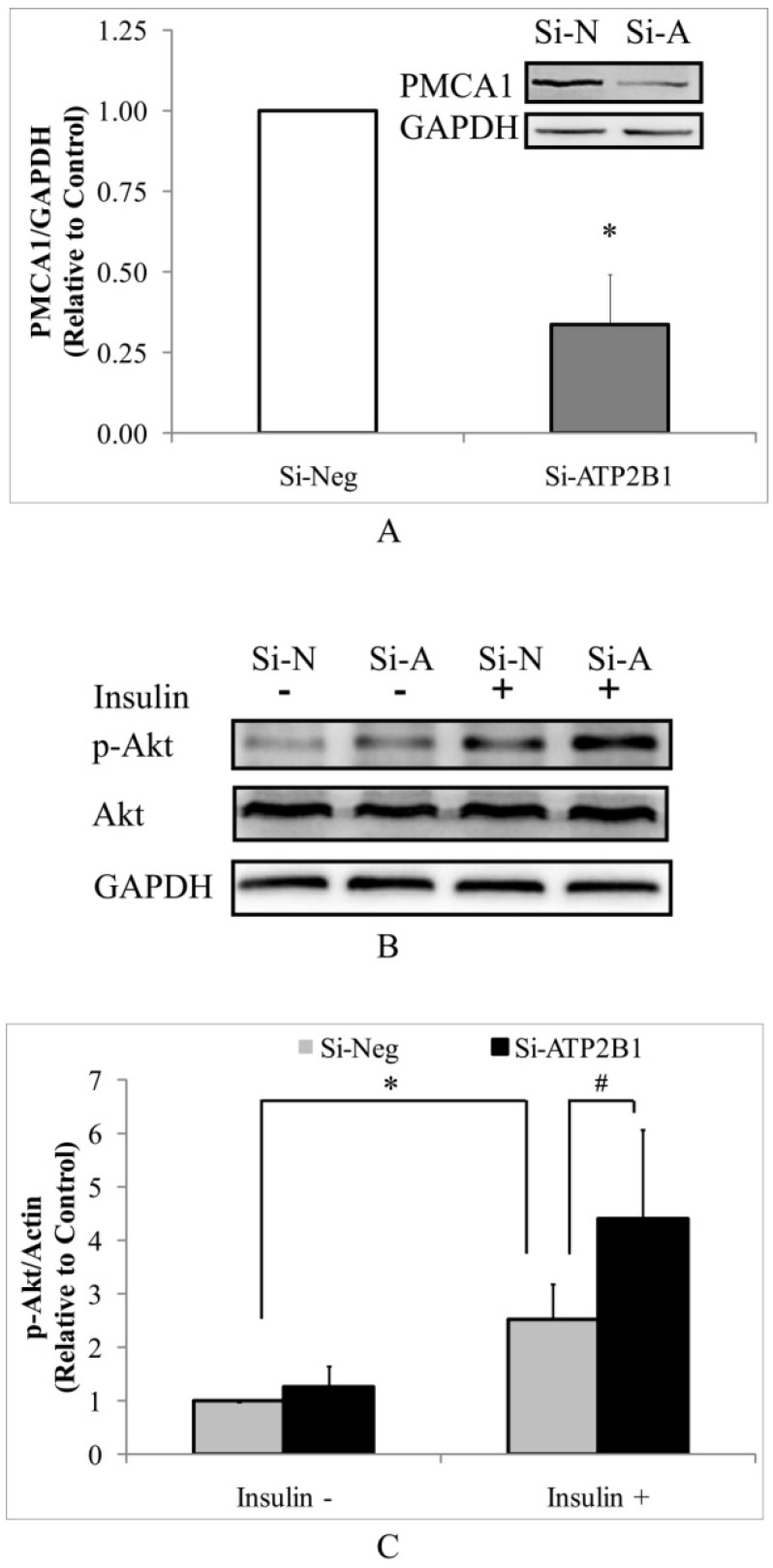

As determined by Western blotting, the PMCA1 protein levels were significantly decreased by about 70% in the si-ATP2B1-transfected HUVECs compared to that in the negative control siRNA-transfected cells (Figure 1A). Then, we detected the levels of phosphor-Akt (Ser473) in HUVECs by Western blotting to explore whether silencing of the ATP2B1 gene influenced insulin sensitivity. As shown in Figure 1B and 1C, higher levels of insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt at serine 473 were found in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs cells, which were increased to almost 1.8 times as much as that in the control cells. These data indicate that ATP2B1 gene silencing could modify insulin sensitivity in endothelial cells.

Figure 1.

Silencing of the ATP2B1 gene results in increased levels of insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt at serine 473 in HUVECs. A. Representative Western blotting results of PMCA1 protein and GAPDH. In addition, the fold changes of PMCA1 protein relative to that in the control cells were quantified by densitometry (n=6). *P<0.05, vs. cells transfected with negative siRNA. HUVECs were starved of serum overnight before stimulation with 100 nM insulin for 30 min. B. Representative Western blotting results of p-Akt, Akt and GAPDH(n=4). C. Fold changes of phosphor-Akt vs. total Akt relative to its basal levels in control cells without insulin stimulation were quantified by densitometry. * P<0.05, vs. negative siRNA-transfected cells stimulated without insulin. #P<0.05, vs. negative siRNA-transfected cells stimulated with insulin.

Increased insulin sensitivity in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs cells may be due to a calcium-dependent signaling pathway

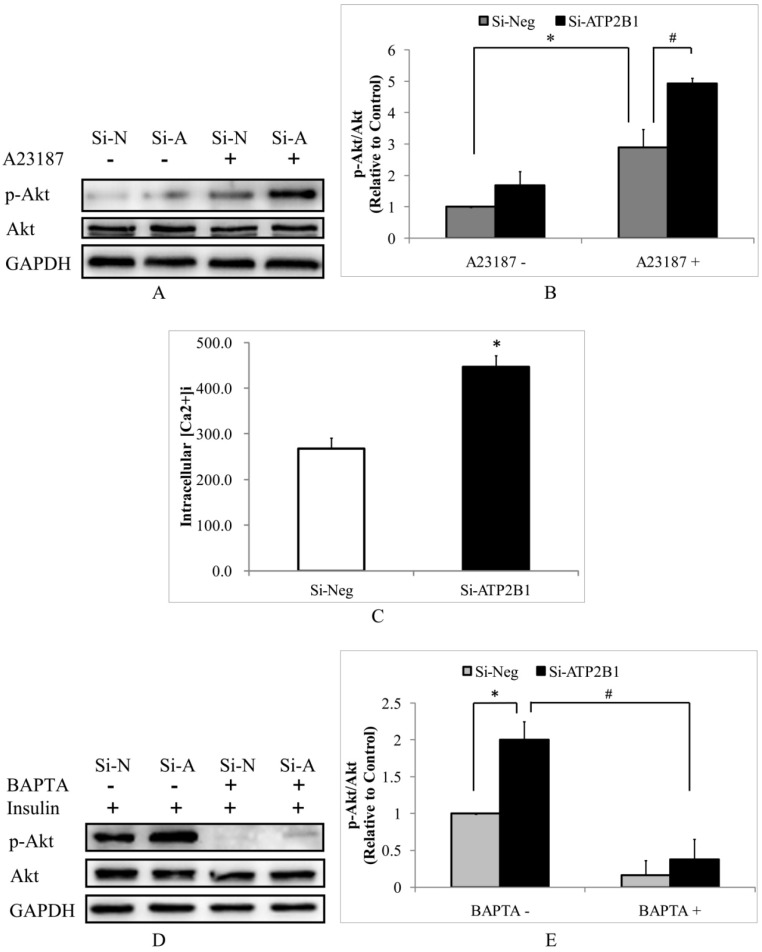

Then, we hypothesized that increased insulin-induced phosphor-Akt (Ser473) levels in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs cells would be calcium-dependent. Consistent with the effects of insulin, the calcium ionopore A23187 (calcimycin) induced 70% higher phosphor-Akt (Ser473) levels in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs compared to that in the control cells (Figure 2A, 2B). These data implicate that the effect of ATP2B1 gene silencing is mediated by an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. To confirm whether intracellular calcium concentrations in HUVECs are altered following ATP2B1 gene silencing, we used the Fluo-3/AM fluorescence assay. As shown in Figure 2C, the intracellular calcium concentration was approximately 450 nM in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs and was 1.7 times as much as that in the control cells. Furthermore, insulin could not increase Akt phosphorylation at Ser 473 both in the control cells and the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs that were co-cultured with BAPTA-AM, an intracellular Ca2+ chelator (Figure 2D, 2E). These results indicate that, similar to the insulin-mediated Akt activation in normal endothelial cells, the increased insulin sensitivity in ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs is calcium-dependent.

Figure 2.

The increased insulin sensitivity in ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs cells may be due to calcium-dependent signaling pathway. HUVECs were starved of serum overnight before stimulation with 500 nM A23187 for 30 min. A. Representative Western blotting results of p-Akt, Akt and GAPDH(n=4). B. Fold changes of phosphor-Akt vs. total Akt relative to its basal levels in the control cells without A23187 stimulation were quantified by densitometry. *P<0.05, vs. negative siRNA-transfected cells without A23187 stimulation. #P<0.05, vs. negative siRNA-transfected cells stimulated with A23187. C. The intracellular concentrations of Ca2+ were measured using fluo-3/AM in HUVECs 48 h after transfection(n=6). *P<0.05, vs. cells transfected with negative siRNA. Following 2 hours of BAPTA administration HUVECs were stimulated with 100 nM insulin for 30 min. D. Representative Western blotting results of phosphor-Akt (Ser473) (n=4). E. Fold changes of phosphor-Akt vs. total Akt relative to its basal levels in control cells were quantified by densitometry. *P<0.05, vs. cells transfected with negative siRNA; #P<0.05, vs. ATP2B1-silenced cells without BAPTA-AM pretreatment.

Increased insulin sensitivity in ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs cells may be explained by calmodulin-dependent Akt activation

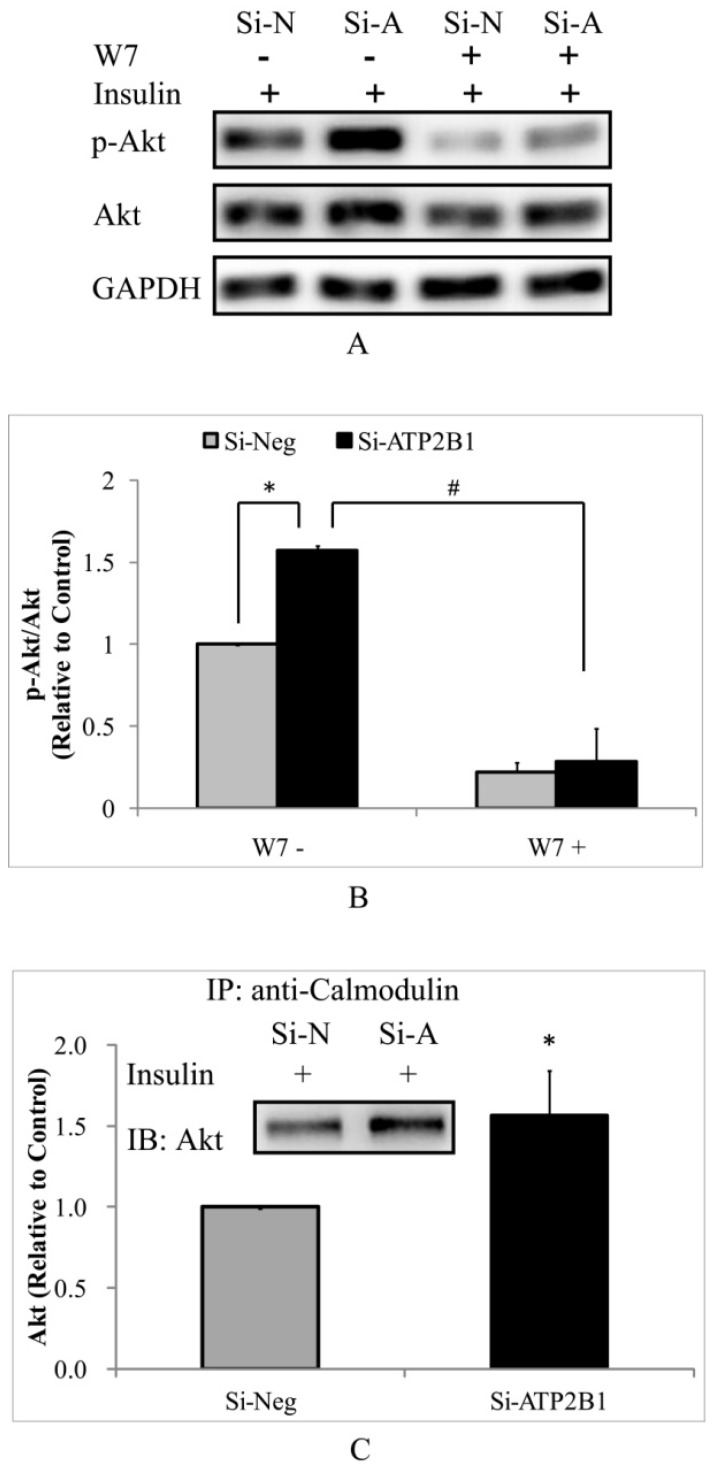

To test whether the higher insulin-induced Akt activity in the ATP2B1-silenced endothelial cells is dependent on calmodulin, a calmodulin-specific antagonist, W7, was used. As expected, the phosphor-Akt (Ser473) levels were totally abolished by W7 both in the control cells and in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs (Figure 3A, 3B). Subsequently, co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed to confirm the role of calmodulin in regulating the activity of Akt. Consistently, our data showed that when stimulated with insulin, the association of Akt with calmodulin in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs was approximately 1.6 times as compared to that in the control cells (Figure 3C). These results suggest that increased insulin sensitivity in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs is calmodulin-dependent, particularly, through higher levels of interaction between calmodulin and Akt.

Figure 3.

Increased insulin sensitivity in ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs cells may be explained by calmodulin-dependent Akt activation. HUVECs were pretreated with W7 for 2 hours followed by insulin stimulation. A. Representative Western blotting results of p-Akt, Akt and GAPDH(n=3). B. Fold changes of phosphor-Akt vs. total Akt relative to its basal levels in control cells were quantified by densitometry. HUVECs were stimulated with 100 nM insulin after overnight serum starvation. Then, co-immunoprecipitation was performed. C. Representative Western blotting results of Akt that was co-immunoprecipitated with calmodulin(n=3). In addition, the fold changes of calmodulin-associated Akt relative to its basal levels in the control cells were quantified by densitometry. *P<0.05, vs. cells transfected with negative siRNA.

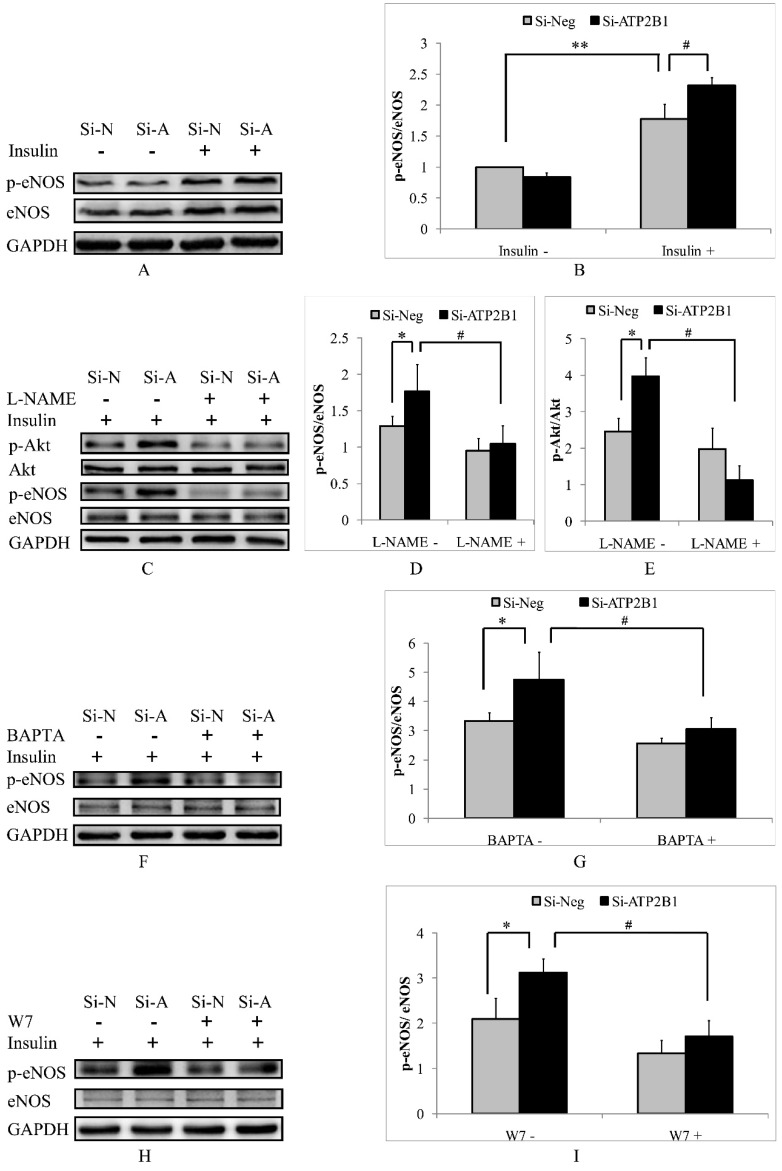

Increased insulin sensitivity in ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs is dependent on the calcium-calmodulin-eNOS signaling pathway

It has been reported that eNOS, a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzyme, plays an important role in regulating the activation of Akt23. Therefore, we focused on the potential contribution of eNOS. In our current article, we observed that the insulin-stimulated phosphorylation levels of eNOS at site ser1177 in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs were 1.3 times as compared with that in the control cells (Figure 4A, 4B). To confirm whether eNOS mediates the activation of Akt, we inhibited the eNOS activity by pretreatment with an eNOS inhibitor, L-NAME. As shown in Figure 4C, 4D and 4E, the activation of Akt was abolished by the inhibition of eNOS activity with L-NAME, indicating that Akt can be activated by an eNOS-dependent pathway. Next, we explored whether higher eNOS activity in the ATP2B1 gene siRNA treated-endothelial cells was induced by a calcium-calmodulin dependent manner. Similar to insulin-induced phosphor-Akt (Ser473) (Figure 2 and 3), the intracellular Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM and the calmodulin antagonist W7 abolished the levels of insulin-induced phosphor-eNOS (Ser1177) in both the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs and the control cells (Figure 4F, 4G, 4H and 4I). The above results suggest that increased insulin sensitivity in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs may be mediated via a higher level of intracellular calcium concentration and that the effect is dependent on the calcium-calmodulin-eNOS signaling pathway.

Figure 4.

Increased insulin sensitivity in ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs is dependent on the calcium-calmodulin-eNOS signaling pathway. HUVECs were stimulated with 100 nM insulin after overnight serum starvation. A. Representative Western blotting results of p-eNOS, eNOS and GAPDH (n=4). B. Fold changes of phosphor-eNOS vs. total eNOS relative to its basal levels in control cells were quantified by densitometry. HUVECs were treated with L-NAME for 2 hours before they were stimulated with insulin. ** 0.05<P<0.001, vs. negative siRNA-transfected cells without insulin stimulation. #P<0.05, vs. cells transfected with negative siRNA. C. Representative Western blotting results of p-Akt, Akt, p-eNOS, eNOS and GAPDH (n=3). Fold changes of phosphor-eNOS vs. total eNOS (D) and phosphor-Akt vs. total Akt (E) relative to the basal levels in control cells were quantified by densitometry. * P<0.05, vs. negative siRNA-transfected cells. #P<0.05, vs. si-Neg cells precultured without L-NAME. HUVECs were stimulated with 100 nM insulin after being treated with BAPTA or W7 for 2 hours. Representative Western blotting of p-eNOS, eNOS and GAPDH in cells pretreated with BATPA (F) or W7 (H) (n=3). Fold changes of phosphor-eNOS vs. total eNOS in cells cultured with BATPA (G) or W7 (I) were quantified by densitometry. * P<0.05, vs. negative siRNA-transfected cells. #P<0.05, vs. si-Neg cells without BAPTA-AM or W7 pretreatment.

Discussion

rs17249754, a SNP located in the intron region of the ATP2B1 gene, was found to be associated with a higher risk of T2DM 18. However, we know little about the implications of the ATP2B1 gene on T2DM. In the present study, our data demonstrated that ATP2B1 gene silencing increased insulin sensitivity in endothelial cells by enhancing intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and the Ca2+/calmodulin signaling pathway directly. Moreover, ATP2B1 gene silencing also resulted in greater insulin-induced eNOS activity via the Ca2+/calmodulin signaling pathway. Additionally, the Ca2+-associated activation of eNOS was involved in modifying insulin sensitivity in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs.

Almost eight years ago, the ATP2B1 gene was identified to be associated genome-wide significantly with systolic and diastolic blood pressure and/or with hypertension 11, 12, 24. Since then, strong associations between the ATP2B1 gene loci and blood pressure or hypertension have also been reported in different ethnic groups 13, 14, 18. Additionally, SNPs related to ATP2B1 gene have been found to be genetically associated with pulse pressure, coronary artery disease and coronary artery calcification and myocardial infarction in chronic kidney disease 19. These genetic studies in large populations indicate that the ATP2B1 gene has pleiotropic effects on the cardiovascular system. However, little is known about how the ATP2B1 gene effects on cardiovascular function. Because of the association of the ATP2B1 gene with hyperlipidemia and diabetes, it is hypothesized that indirect effects of the ATP2B1 gene on metabolism may play a potential role in regulating cardiovascular function 18. Evidence from experimental studies shows that increase in blood pressure induced by ATP2B1 gene knockdown may be due to impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation, increased contractility of mesenteric arteries, or elevated phenylephrine-induced vasoconstriction 19. In our current study, ATP2B1 gene silencing led to increased insulin-induced Akt activation in endothelial cells that were cultured in vitro. The potential role of the ATP2B1 gene in endothelial cell insulin sensitivity could also be an underlying mechanism involved in its' effect on the cardiovascular system.

In the current study, we hypothesized that increased insulin-induced phosphor-Akt (Ser473) levels in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs cells would be calcium-dependent. Intracellular Ca2+, which exists ubiquitously in mammalian cells, is a well-known secondary messenger and is critical in controlling a variety of cellular processes 25. It has been reported that the changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration are involved in regulating Akt activity. SKF-96365, a calcium antagonist, has been reported to decrease intracellular Ca2+ concentrations through inhibiting the store-operated Ca2+ entry-mediated Ca2+ influx which consequently attenuates Akt activity in colon cancer cell lines 26. Furthermore, increased intracellular Ca2+ is responsible for insulin-induced Akt activation, which results in leptin secretion in adipocytes 21. These results indicate that Ca2+ is required for insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 in endothelial cells. In the present study, we observed that ATP2B1 gene silencing resulted in higher intracellular Ca2+ and simultaneously led to enhanced insulin-induced AKT activity. Furthermore, administration of a calcium chelator BAPTA-AM prior to insulin treatment blocked insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation at Ser473. Therefore, the enhanced insulin sensitivity observed in the ATP2B1-silenced endothelial cells may be due to higher levels of intracellular Ca2+.

Calmodulin, one of the most important intracellular Ca2+ sensors, interacts with many different proteins and is involved in regulating a wide variety of cellular physiological functions 27. Recent evidence suggests that calmodulin plays a critical role in regulating the activity of Akt. Research data collected by nuclear magnetic resonance confirms that the Pleckstrin homology domain (PHD), a conserved domain that is found in the N-terminus of Akt, is a critical domain that binds with calmodulin 28-30. These results indicate that the direct binding between calmodulin and Akt may be involved in regulating Akt activity. However, the previous studies have drawn different conclusions about whether the binding of calmodulin with Akt results in the decrease or increase in Akt activity. One of the previous studies declared that calmodulin competed with PI(3,4,5)3 for the PH domain of Akt, thereby decreasing the affinity of PI(3,4,5)3 and attenuating Akt activity30. Others have reported that calmodulin could mediate EGF-induced Akt activation by binding and targeting Akt to the plasma membrane to be activated by PI-3 kinase in c-Myc-overexpressing mouse mammary carcinoma cells 28, 31. In addition, the results obtained in PC12 cells and chicken spinal cord motor neurons showed that Ca2+ and calmodulin play a central role in the activation of Akt 32. Furthermore, a novel calmodulin-binding motif was found in the Akt PHD, which was mapped to two loops that are adjacent to the PI(3,4,5)3 binding site and these results suggest a synergetic relationship between calmodulin and PI(3,4,5)3 in the activation of Akt 28. In line with these previous studies, we observed that the specific antagonist of calmodulin W7 almost completely abolished the insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation at serine 473 in the control cells and the ATP2B1-silenced endothelial cells. Additionally, the effect was mediated by the binding of Akt to calmodulin as shown in the co-immunoprecipitation experiment. These results indicate that calmodulin is necessary for insulin-induced Akt activation in endothelial cell. In addition, the interaction between calmodulin and Akt may be an important mechanism that explains why knockdown of ATP2B1 gene increases insulin sensitivity. Difference in experimental design maybe a possible reason for the contradictory conclusion in the research conducted by Rihe Liu 30. These studies were performed using the pulldown assay, phosphoinositide membrane strip and GST-tagged Akt(PHD) protein 30, whereas others were conducted with native and untagged Akt(PHD) protein and physiologically relevant membrane mimetic containing PS 28. Furthermore, our research was performed in primary endothelial cells cultured in vitro, and others in mammary carcinoma cell lines 31, 33, PC12, and chicken spinal cord motoneurons 32. To clarify how calmodulin interacts with Akt and how the interplay between calmodulin and Akt regulates Akt activation, further investigations are required.

eNOS, also known as endothelial nitric oxide synthase, is specifically expressed in endothelial cells and is responsible for NO generation 34. The enzymatic activity of eNOS has been reported to be dependent on Ca2+/calmodulin binding 35, 36. PMCAs (a group of proteins encoded by ATP2B1-4 gene), with its emerging role in regulating Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzymes, removes calcium from the cell to the extracellular environment and inhibits the activity of eNOS by directing it to low-calcium cellular microenvironments 37. Additionally, PMCAs proteins reduce NO production by binding with eNOS and inhibiting its activity 37. Consistently, in the present research higher levels of intracellular Ca2+ concentration and phosphor-eNOS (Ser1177) were observed in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs. However, impaired NO production and lower levels of phosphor-eNOS (Ser1177) were reported in systemic heterozygous ATP2B1 null mice 16. The differences in experimental design may account for the adverse results in these studies. First, the research conducted by Akira Fujiwara and his colleagues was performed in systemic heterozygous ATP2B1-null mice in vivo 16, while we and Angel L. Armesilla 37 conducted studies in endothelial cells cultured in vitro. Alternatively, ATP2B1 gene was knockdown systemically but not specifically in endothelial cells in mice 16. Therefore, the possibility of other mechanisms cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, ATP2B1 gene silencing-mediated increases in eNOS activity in endothelial cells were observed at 48-72 hours after the transient transfection of siRNA in the present study. However, the decrease in eNOS activity mediated by systemic heterozygous ATP2B1 gene knockdown was examined in mice at 3 months of age 16. To clarifying the influence of the ATP2B1 gene on the activity of eNOS, further investigations are warranted in endothelial cell-specific ATP2B1 gene knockout mice.

In addition to eNOS, Akt is also known as a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzyme 29. Additionally, an abundance of evidence has shown that Akt can activate eNOS by directly phosphorylating eNOS at serine 117738. However, eNOS is also involved in regulating the activation of Akt through its catalyzed product NO 23. In this study, in line with the activity of Akt higher levels of phosphor-eNOS (Ser1177) were observed in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs. Moreover, the eNOS inhibitor L-NAME blocked the activation of both eNOS and Akt by insulin. Additionally, phosphor-eNOS (Ser1177) levels were also abolished by the calcium chelator BAPTA-AM and the calmodulin antagonist W7. These results suggest that in addition to the Ca2+/calmodulin/Akt signaling pathway, enhanced insulin sensitivity in the ATP2B1-silenced endothelial cells are dependent on an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and the subsequent activation of the Ca2+/calmodulin/eNOS/Akt signaling pathway.

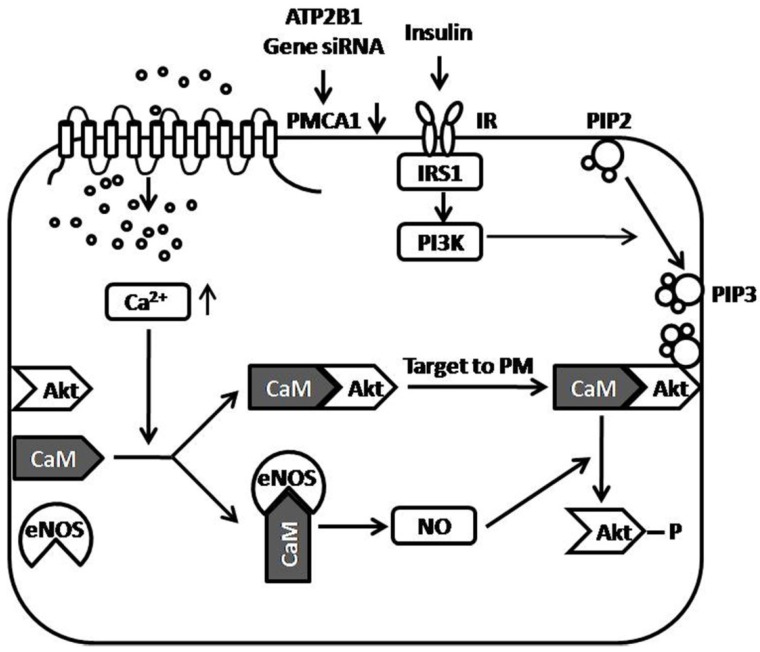

In summary, we reported that ATP2B1 gene silencing increased insulin sensitivity in endothelial cells in the present study. Enhancing intracellular Ca2+ concentration by ATP2B1 gene silencing, may be one of the central mechanisms involved in the increased insulin sensitivity observed in the ATP2B1-silenced endothelial cells. Additionally, facilitated Akt Activation via the Ca2+/calmodulin signaling pathway and Ca2+-associated eNOS activation was involved in modifying insulin sensitivity in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs. Furthermore, in attempt to showing how the PMCA1 protein regulates insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation, a figure of proposed model is provided (Figure 5). However, there are some limitations in the present study. First, this research was conducted on HUVECs cultured in vitro, and in vivo animal experiments were not performed. Therefore, we do not know whether the silencing of the ATP2B1 gene increases insulin sensitivity in endothelial cells in vivo. Second, our results suggest that facilitated Akt activation via the Ca2+/calmodulin signaling pathway and Ca2+-associated eNOS activation is involved in modifying insulin sensitivity in the ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs, but the relationship between Akt and eNOS is not clearly established and the mechanism that is involved in how the regulation of Akt activity by activated eNOS is still unclear. Third, calmodulin, as mentioned above, is a versatile intracellular Ca2+ sensors that interacts with many different proteins, including Akt 27, eNOS 27, and, most importantly, PMCA1 protein 19, 39 etc. Use of the calmodulin inhibitor W7 may mask the effects of other Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent proteins, such as PMCA1 protein, on Akt activation. Therefore, it is not clear whether the interaction between calmodulin and PMCA1 protein is also involved in the increased insulin sensitivity induced by ATP2B1 gene silencing. Last, as shown in Figure 1A, siRNA treatment of the ATP2B1 gene decreased but not totally knockout the expression of the PMCA1 protein. Therefore, we cannot draw the conclusion that the interaction between calmodulin and the Akt PH domain is crucial for Akt activation.

Figure 5.

Proposed model of the role of the PMCA1 protein in regulating insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation. ATP2B1 gene silencing, which results in decreased expression of the PMCA1 protein, leads to enhanced intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in endothelial cells. Enhanced Ca2+ concentrations by ATP2B1 gene silencing facilitate insulin-induced Akt activation through Ca2+/calmodulin signaling pathway. Moreover, ATP2B1 gene silencing results in greater insulin-induced eNOS activity via the Ca2+/calmodulin signaling pathway. Additionally, the Ca2+-associated activation of eNOS was involved in modifying insulin sensitivity in ATP2B1-silenced HUVECs. ATP2B1: ATPase plasma membrane Ca2+ transporting 1; PMCA1: Plasma Membrane Calcium ATPase 1; IR: insulin receptor; IRS1: insulin receptor substrate 1; CaM: calmodulin; Akt: protein kinase B; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO: nitric oxide; PM: plasma membrane; PIP2: Phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-biphosphate; PIP3: Phosphatidylinositol-3, 4, 5-triphosphate; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Joint Project of the People's Government of Luzhou and Sichuan Medical University under Grant no 2015SX-0032 and by the Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University under Grant no 15046.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in the submitted article are our own and not an official position of the institution or funder.

References

- 1.Kuboki K, Jiang ZY, Takahara N. et al. Regulation of endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthase gene expression in endothelial cells and in vivo: a specific vascular action of insulin. Circulation. 2000;101:676–81. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King GL, Park K, Li Q. Selective Insulin Resistance and the Development of Cardiovascular Diseases in Diabetes: The 2015 Edwin Bierman Award Lecture. Diabetes. 2016;65:1462–71. doi: 10.2337/db16-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliver FJ, de la Rubia G, Feener EP. et al. Stimulation of endothelin-1 gene expression by insulin in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider DJ, Absher PM, Ricci MA. Dependence of augmentation of arterial endothelial cell expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 by insulin on soluble factors released from vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 1997;96:2868–76. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muniyappa R, Montagnani M, Koh KK. et al. Cardiovascular actions of insulin. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:463–91. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khamaisi M, Katagiri S, Keenan H. et al. PKCdelta inhibition normalizes the wound-healing capacity of diabetic human fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:837–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI82788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laakso M, Sarlund H, Salonen R. et al. Asymptomatic atherosclerosis and insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:1068–76. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.4.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang ZY, Lin YW, Clemont A. et al. Characterization of selective resistance to insulin signaling in the vasculature of obese Zucker (fa/fa) rats. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:447–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI5971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuchiya K, Tanaka J, Shuiqing Y. et al. FoxOs integrate pleiotropic actions of insulin in vascular endothelium to protect mice from atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2012;15:372–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q, Park K, Li C. et al. Induction of vascular insulin resistance and endothelin-1 expression and acceleration of atherosclerosis by the overexpression of protein kinase C-beta isoform in the endothelium. Circ Res. 2013;113:418–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy D, Ehret GB, Rice K. et al. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Genet. 2009;41:677–87. doi: 10.1038/ng.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho YS, Go MJ, Kim YJ. et al. A large-scale genome-wide association study of Asian populations uncovers genetic factors influencing eight quantitative traits. Nat Genet. 2009;41:527–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi F, Isono M, Katsuya T. et al. Blood pressure and hypertension are associated with 7 loci in the Japanese population. Circulation. 2010;121:2302–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.904664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu X, Wang L, Lin X. et al. Genome-wide association study in Chinese identifies novel loci for blood pressure and hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:865–74. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin YB, Lim JE, Ji SM. et al. Silencing of Atp2b1 increases blood pressure through vasoconstriction. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1575–83. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32836189e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujiwara A, Hirawa N, Fujita M. et al. Impaired nitric oxide production and increased blood pressure in systemic heterozygous ATP2B1 null mice. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1415–23. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi Y, Hirawa N, Tabara Y. et al. Mice lacking hypertension candidate gene ATP2B1 in vascular smooth muscle cells show significant blood pressure elevation. Hypertension. 2012;59:854–60. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.165068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heo SG, Hwang JY, Uhmn S. et al. Male-specific genetic effect on hypertension and metabolic disorders. Hum Genet. 2014;133:311–9. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Little R, Cartwright EJ, Neyses L. et al. Plasma membrane calcium ATPases (PMCAs) as potential targets for the treatment of essential hypertension. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;159:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Leva F, Domi T, Fedrizzi L. et al. The plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase of animal cells: structure, function and regulation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;476:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Ali Y, Lim CY. et al. Insulin-stimulated leptin secretion requires calcium and PI3K/Akt activation. Biochem J. 2014;458:491–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mima S, Tsutsumi S, Ushijima H. et al. Induction of claudin-4 by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and its contribution to their chemopreventive effect. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1868–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong R, Chen W, Feng W. et al. Exogenous Bradykinin Inhibits Tissue Factor Induction and Deep Vein Thrombosis via Activating the eNOS/Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Akt Signaling Pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:1592–606. doi: 10.1159/000438526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton-Cheh C, Johnson T, Gateva V. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight loci associated with blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009;41:666–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jing Z, Sui X, Yao J. et al. SKF-96365 activates cytoprotective autophagy to delay apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells through inhibition of the calcium/CaMKIIgamma/AKT-mediated pathway. Cancer Lett. 2016;372:226–38. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tidow H, Nissen P. Structural diversity of calmodulin binding to its target sites. FEBS J. 2013;280:5551–65. doi: 10.1111/febs.12296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agamasu C, Ghanam RH, Xu F. et al. The Interplay between Calmodulin and Membrane Interactions with the Pleckstrin Homology Domain of Akt. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:251–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.752816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agamasu C, Ghanam RH, Saad JS. Structural and Biophysical Characterization of the Interactions between Calmodulin and the Pleckstrin Homology Domain of Akt. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:27403–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.673939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong B, Valencia CA, Liu R. Ca(2+)/calmodulin directly interacts with the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25131–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coticchia CM, Revankar CM, Deb TB. et al. Calmodulin modulates Akt activity in human breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:545–60. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0097-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egea J, Espinet C, Soler RM. et al. Neuronal survival induced by neurotrophins requires calmodulin. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:585–97. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200101023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deb TB, Coticchia CM, Dickson RB. Calmodulin-mediated activation of Akt regulates survival of c-Myc-overexpressing mouse mammary carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38903–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shu X, Keller TCt, Begandt D. et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the microcirculation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:4561–75. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Presta A, Liu J, Sessa WC. et al. Substrate binding and calmodulin binding to endothelial nitric oxide synthase coregulate its enzymatic activity. Nitric Oxide. 1997;1:74–87. doi: 10.1006/niox.1996.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsubara M, Hayashi N, Titani K. et al. Circular dichroism and 1H NMR studies on the structures of peptides derived from the calmodulin-binding domains of inducible and endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in solution and in complex with calmodulin. Nascent alpha-helical structures are stabilized by calmodulin both in the presence and absence of Ca2+ J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23050–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holton M, Mohamed TM, Oceandy D. et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity is inhibited by the plasma membrane calcium ATPase in human endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:440–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B. et al. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–5. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopreiato R, Giacomello M, Carafoli E. The plasma membrane calcium pump: new ways to look at an old enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:10261–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.O114.555565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]