Abstract

Background The correlation between severity and long-term outcomes of pediatric myocarditis have been reported, however this correlation in adults has rarely been studied.

Materials and Methods This nationwide population-based cohort study used data from the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan. Patients aged < 75 and > 18 years admitted to an intensive care unit due to acute myocarditis were enrolled and divided into three groups according to mechanical circulatory support (MCS) after excluding major comorbidities. All-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, and heart failure hospitalization were evaluated from January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2011.

Results There were 1145 patients with acute myocarditis (mean age 40.2 years, SD: 14.8 years), of which 851 did not require MCS, 99 underwent intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) support, and 195 extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support. There was no significant difference in heart failure hospitalization between the three groups after index admission. The incidence of cardiovascular death after discharge ranged from 10 % to 22%, which was highest in the ECMO group, and was also significantly different between the three groups within 3 months (p<0.001) but it disappeared after 3 months (p=0.458). The trend was also noted in incidence of all-cause mortality.

Conclusions The severity of acute myocarditis did not affect long-term outcomes, however, it was associated with cardiovascular/all-cause death within 3 months after discharge.

Keywords: Acute myocarditis, mechanical circulatory support, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, heart failure, cardiovascular death.

Introduction

Myocarditis refers to the clinical and histological manifestations of a broad range of pathological immune processes in the heart.1 It can lead to diverse clinical outcomes ranging from an asymptomatic course to cardiogenic shock, and its natural history is also highly variable ranging from full recovery to the development of dilated cardiomyopathy or sudden cardiac death. Patients with acute myocarditis often present with non-specific symptoms including chest pain, dyspnea, or palpitations, and it usually affects children.2,3 According to clinical guidelines for acute myocarditis, mechanical circulatory support (MCS) is the mainstay of therapy when medications fail or in some patients with fulminant myocarditis.4 In clinical practice, MCS usually involves extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or a ventricular assist device, and several case-series studies have reported both short-term and long-term outcomes in patients with acute myocarditis under MCS.5-8

The factors influencing the prognosis of acute myocarditis are also important. Several studies have reported that poor left ventricular systolic function at admission or discharge and in-hospital arrhythmia contribute to poor short-term outcomes.9 In contrast, some studies have reported that these factors do not influence the long-term prognosis of acute myocarditis.10 Several other studies have shown a good prognosis for patients receiving adequate hemodynamic support,9-11 and even better outcomes for patients with fulminant myocarditis with adequate MCS.6, 12

However, it is currently unclear whether the initial severity of disease or different management strategies including the use and type of MCS affect the long-term outcomes of survivors, especially cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, most studies on clinical outcomes have focused on pediatric patients with myocarditis.6, 9, 13 According to the reported good outcomes of pediatric patients with acute or even fulminant myocarditis under adequate circulatory support, we hypothesized that the clinical long-term outcomes would be similar in adult patients.

In Taiwan, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) and ECMO support are based on the severity of acute myocarditis, and IABP is usually reserved for adults. The aim of this study was to evaluate in-hospital complications and long-term outcomes of patients not receiving and receiving MCS (IABP or ECMO) using a nationwide health insurance database.

Materials and Methods

Data source and study population

This nationwide population-based cohort study used data from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) released by the Taiwan National Health Research Institute (http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/index.htm). The NHIRD includes more than 99% of the population in Taiwan, and consists of health care data including gender, birth date, use of medications, management and diagnoses based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM; www.icd9-data.com/2007) codes.

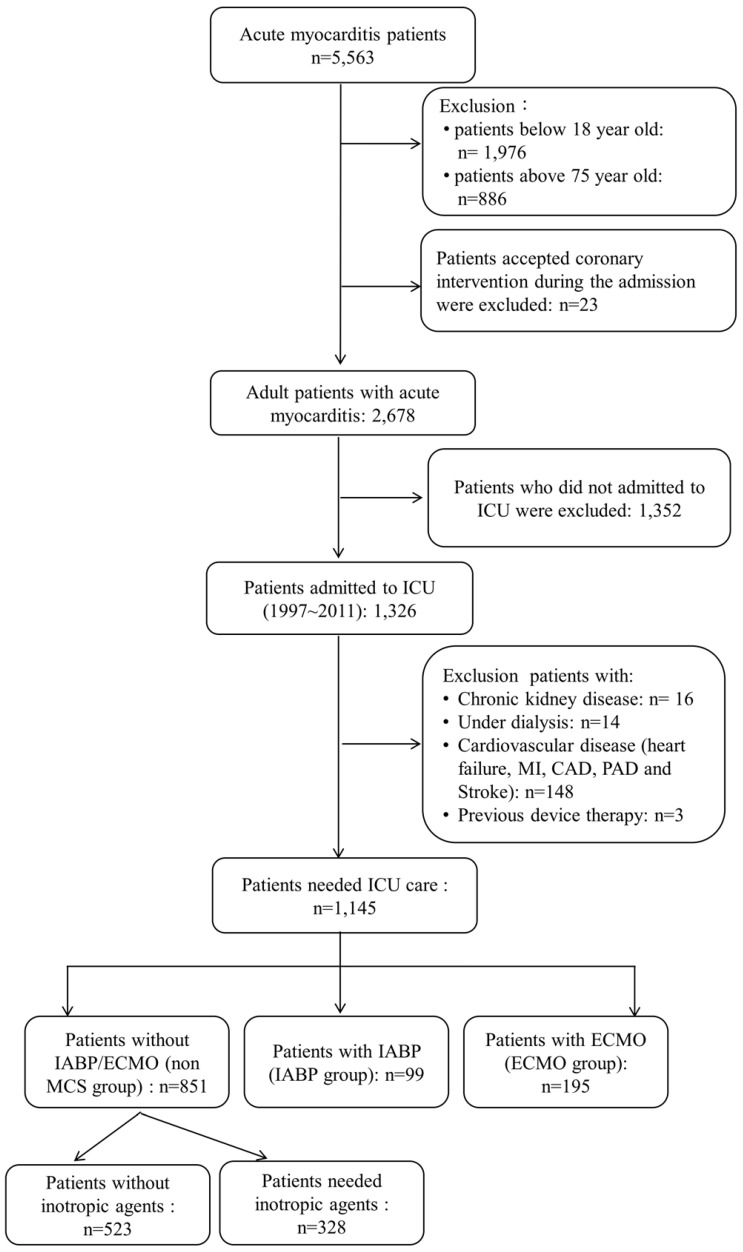

We enrolled 5563 patients who were admitted due to acute myocarditis as listed in the NHIRD from January 1, 1997 to December 31, 2011. Patients aged less than 18 years and more than 75 years were excluded, and those who underwent percutaneous coronary interventions during the admission were also excluded. In order to increase the accuracy of the diagnosis of acute myocarditis and the clinical outcomes, only those admitted to an intensive critical unit were enrolled, and we excluded those with cardiovascular comorbidities including ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, heart failure, a history of stroke, and a history of myocardial infarction. We also excluded the patients with chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease requiring long-term dialysis and those with arrhythmic device implantation. We then divided the remaining patients with acute myocarditis into three groups: those who did not receive MCS (non-MCS group), those receiving only IABP support (IABP group), and those receiving ECMO support (ECMO group). The study enrollment flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study subject selection. CAD: coronary artery disease; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; ICU: intensive care unit; MCS: mechanical circulatory support; MI: myocardial infarction; PAD: peripheral arterial disease

The enrollees' original identification numbers are encrypted in the NHIRD to protect privacy. However, the encryption procedure is consistent, so that linking claims belonging to the same enrollee is feasible and can be followed longitudinally.

Acute myocarditis ascertainment, covariates and definition of management

The diagnosis of acute myocarditis was identified in the NHIRD based on ICD-9-CM code 422. To evaluate the accuracy of this diagnosis, we conducted a validation study in our medical center by reviewing the medical records of hospitalized patients with the ICD-9-CM code of 422. The positive predictive value was 96.5% under the same exclusion criteria in this study. All inpatient files before the index date were used to ascertain comorbidities, which were defined according to ICD-9-CM codes (Table S1). All management-related variables during the index admission for acute myocarditis (ICD-9-CM: 422) were obtained from the database. Confirmation examinations included serum virus marker detection, cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and endomyocardial biopsy (EMB). MCS was defined as IABP or ECMO. Resuscitation programs included defibrillation, intubation with ventilatory support, and cardiac pulmonary resuscitation. Inotropic agents included continuous intravenous infusions with dopamine, norepinephrine and epinephrine, while immunomodulation therapies included intravenous high-dose steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin.

Outcome assessments

The clinical outcomes were defined as cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization and all-cause mortality in this study. Cardiovascular death was defined according to the criteria of the Standardized Definitions for End Point Events in Cardiovascular Trials drafted by the Food and Drug Administration,14 which included death due to heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, stroke and other cardiovascular causes such as dysrhythmia, pulmonary embolism, aortic aneurysm rupture or peripheral arterial disease and sudden cardiac death in survivors from acute myocarditis. Heart failure hospitalization was defined according to the primary diagnosis of admission was heart failure (ICD-9-CM: 428). Major cardiovascular diseases and heart failure hospitalization were validated before, and the positive predictive values ranged from 70~97%15 and around 80%, respectively.16 Secondary outcomes included ventricular tachycardia/ fibrillation (VT/VF), long-term dialysis, stroke, and in-hospital complications, including new onset of high-degree atrioventricular block, VT/VF, acute renal failure, need of hemodialysis, and stroke.

Statistics

The patients' baseline characteristics, management and resuscitation strategies during the index admission were compared between the study groups using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. We compared the risk of in-hospital complications among the study groups using multivariate logistic regression analysis with adjustments for age, gender and comorbidities (Table 1). For the survivors from acute myocarditis, we compared the cardiovascular death and secondary outcomes between study groups using multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis with adjustments for age, gender, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), maintenance oral medications (Table 1) and in-hospital complications including VT/VF, high-degree atrioventricular block and acute renal failure. Due to that death might be a competing risk of HF hospitalization, we performed Fine and Gray's sub-distribution hazard model when studying HF hospitalization. Finally, the cumulative incidence of primary outcomes (heart failure hospitalization, cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality) for each study group was calculated using the log-rank test. All data analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 22 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and management during admission

| Variable | Total | Non-MCS | IABP | ECMO | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1,145 | 851 | 99 | 195 | - |

| Male gender | 677 (59.3) | 530 (62.5) | 59 (59.6) | 88 (45.1) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 40.2±14.8 | 39.6±15.0 | 44.8±15.6 | 40.5±13.1 | 0.004 |

| Age group (years) | 0.003 | ||||

| 18~39 | 614 (53.6) | 470 (55.2) | 45 (45.5) | 99 (50.8) | |

| 40~59 | 383 (33.4) | 276 (32.4) | 30 (30.3) | 77 (39.5) | |

| ≧60 | 148 (12.9) | 105 (12.3) | 24 (24.2) | 19 (9.7) | |

| Underlying disease | |||||

| Hypertension | 112 (9.8) | 88 (10.3) | 12 (12.1) | 12 (6.2) | 0.148 |

| Diabetes | 91 (7.9) | 68 (8.0) | 13 (13.1) | 10 (5.1) | 0.056 |

| Dyslipidemia | 35 (3.1) | 29 (3.4) | 5 (5.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0.051 |

| COPD | 40 (3.5) | 26 (3.1) | 6 (6.1) | 8 (4.1) | 0.268 |

| Examination during the admission | |||||

| Heart MRI | 51 (4.5) | 40 (4.7) | 4 (4.0) | 7 (3.6) | 0.777 |

| Cardiac biopsy | 81 (7.1) | 28 (3.3) | 8 (8.1) | 45 (23.1) | <0.001 |

| Serum virus detection | 747 (65.2) | 516 (60.6) | 65 (65.7) | 166 (85.1) | <0.001 |

| Coronary angiography | 427 (43.6) | 297 (38.1) | 60 (75.0) | 70 (58.8) | <0.001 |

| Intravenous medications during the admission | |||||

| Dobutamine | 361 (31.5) | 199 (23.4) | 57 (57.6) | 105 (53.8) | <0.001 |

| Milrinone | 34 (3.0) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (3.0) | 29 (14.9) | <0.001 |

| Dopamine | 557 (48.6) | 312 (36.7) | 73 (73.7) | 172 (88.2) | <0.001 |

| Norepinephrine | 243 (21.2) | 85 (10.0) | 39 (39.4) | 119 (61.0) | <0.001 |

| Epinephrine | 298 (26.0) | 107 (12.6) | 37 (37.4) | 154 (79.0) | <0.001 |

| High dose of steroid | 51 (4.5) | 20 (2.4) | 5 (5.1) | 26 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| IVIG | 27 (2.4) | 4 (0.5) | 2 (2.0) | 21 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| Heparin | 545 (47.6) | 291 (34.2) | 73 (73.7) | 181 (92.8) | <0.001 |

| Enoxaparin | 121 (10.6) | 97 (11.4) | 12 (12.1) | 12 (6.2) | 0.087 |

| Oral medication for maintain usage | |||||

| ACEi/ARB | 503 (43.9) | 386 (45.4) | 48 (48.5) | 69 (35.4) | 0.026 |

| Beta blocker | 375 (32.8) | 283 (33.3) | 39 (39.4) | 53 (27.2) | 0.089 |

| Digoxin | 206 (18.0) | 145 (17.0) | 24 (24.2) | 37 (19.0) | 0.195 |

| K sparing diuretics | 152 (13.3) | 97 (11.4) | 28 (28.3) | 27 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 61 (5.3) | 47 (5.5) | 8 (8.1) | 6 (3.1) | 0.173 |

| Antiplatelets | 514 (44.9) | 407 (47.8) | 50 (50.5) | 57 (29.2) | <0.001 |

ACEi/ARB: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blocker; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin; MCS: mechanical circulation support; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Results

In total, 1145 patients with acute myocarditis (mean age 40.2 years, SD 14.8 years) were enrolled in this study, of whom most were young adults (614/53.6%, 18~39 years). Of these patients, 851 did not need MCS and 294 patients received MCS, including 99 with only IABP and 195 with ECMO support, composited of 60 patients had ECMO support only and 135 patients had both IABP and ECMO support. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The distribution of comorbidities was similar among the study groups. There was no significant difference in age between the three study groups.

Management during the admission

All of the patients enrolled in this study needed ICU care, and a majority needed inotropic agents for shock (dopamine: 48.6%; norepinephrine: 21.2% and epinephrine: 26.0%), especially those who received MCS. With regards to examinations to confirm the diagnosis and detect the origin of acute myocarditis, most patients underwent serum viral marker detection and a few underwent CMR and a biopsy, especially those in the ECMO group (23.1%).

With regards to intensive management and resuscitation strategies, intubation with ventilatory support and resuscitation were required more in the MCS group than in the non-MCS group, and especially in the ECMO group. In addition, the length of ventilator use and cardiac pulmonary resuscitation were also longer in the ECMO group. There were significant differences in all forms of intensive therapy including continuous venovenous hemofiltration and temporary pacemaker placement, and also in the length of ICU and hospital stay (Table S2).

In-hospital complications

The incidence of in-hospital complications was higher in the MSC group than in the non-MCS group, and especially in the ECMO group (Table 2). Acute renal failure was the most common complication, and especially in the ECMO group (25.6%). In addition, VT/VF, acute renal failure, need of hemodialysis, new stroke and in-hospital mortality rates were highest in the ECMO group. Compared to the patients without MCS, those with MCS had higher rates of VT/VF (vs. IABP group: p=0.023; vs. ECMO group: p<0.001) and in-hospital mortality (vs. IABP group: p=0.002; vs. ECMO group: p<0.001). There was a trend of more renal damage in the IABP group (acute renal failure: p=0.063; need of hemodialysis: p=0.055), and a significantly higher incidence in the ECMO group (acute renal failure: p=<0.001; need of hemodialysis: p<0.001). However, there were no differences in high-degree atrioventricular block between the three groups. Comparing the IABP and ECMO groups, the ECMO group had a higher incidence of acute renal failure and in-hospital mortality than the IABP group.

Table 2.

In-hospital complications

| Variable | Number of events (%) | Adjusted odds ratio and 95% CI‡ | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non MCS (n = 851) |

IABP (n = 99) |

ECMO (n = 195) |

IABP vs. Non-MCS | ECMO vs. Non-MCS | ECMO vs. IABP | |||||||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||||||

| VT/VF | 50 (5.9) | 12 (12.1) | 34 (17.4) | 2.19 (1.12-4.32) | 0.023 | 2.98 (1.85-4.81) | <0.001 | 1.36 (0.66-2.80) | 0.405 | |||

| High degree AV block | 61 (7.2) | 8 (8.1) | 11 (5.6) | 1.14 (0.53-2.48) | 0.738 | 0.80 (0.41-1.57) | 0.523 | 0.70 (0.27-1.83) | 0.471 | |||

| Acute renal failure | 61 (7.2) | 13 (13.1) | 50 (25.6) | 1.86 (0.97-3.56) | 0.063 | 4.71 (3.08-7.23) | <0.001 | 2.54 (1.28-5.03) | 0.007 | |||

| Need of hemodialysis | 20 (2.4) | 6 (6.1) | 24 (12.3) | 2.52 (0.98-6.50) | 0.055 | 5.77 (3.07-10.83) | <0.001 | 2.29 (0.88-5.92) | 0.088 | |||

| New onset of stroke | 19 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) | 13 (6.7) | 0.42 (0.06-3.20) | 0.403 | 2.92 (1.40-6.09) | 0.004 | 6.95 (0.89-54.5) | 0.065 | |||

| Pneumonia | 114 (13.4) | 12 (12.1) | 24 (12.3) | 0.83 (0.44-1.59) | 0.581 | 0.87 (0.54-1.41) | 0.576 | 1.05 (0.49-2.21) | 0.907 | |||

| Sepsis | 115 (13.5) | 24 (24.2) | 36 (18.5) | 1.87 (1.12-3.11) | 0.017 | 1.28 (0.84-1.95) | 0.252 | 0.69 (0.38-1.25) | 0.218 | |||

| In-hospital death | 71 (8.3) | 19 (19.2) | 76 (39.0) | 2.47 (1.40-4.36) | 0.002 | 6.86 (4.66-10.12) | <0.001 | 2.78 (1.53-5.05) | 0.001 | |||

Abbreviation: AV block: atrioventricular block; VT/VF: ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; MCS: mechanical circulation support

‡ Adjusted for age, gender, and the baseline characteristics listed in Table 1

Long-term outcomes in the survivors from acute myocarditis

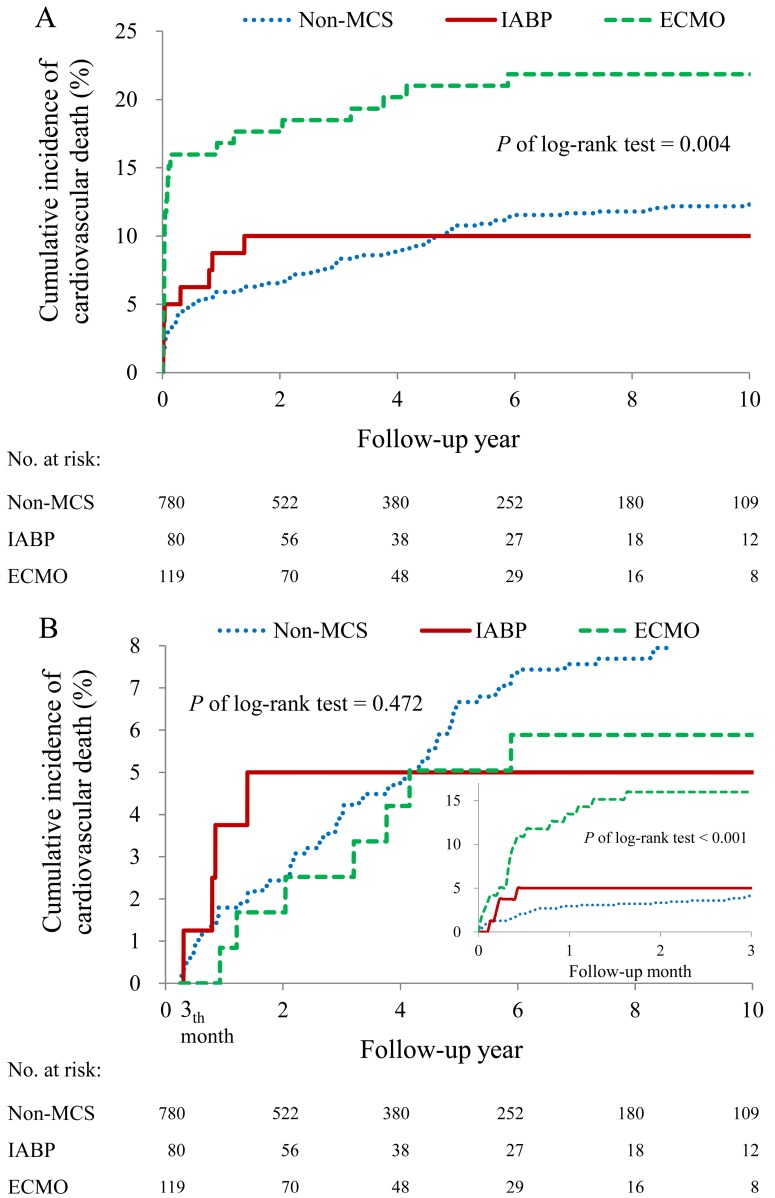

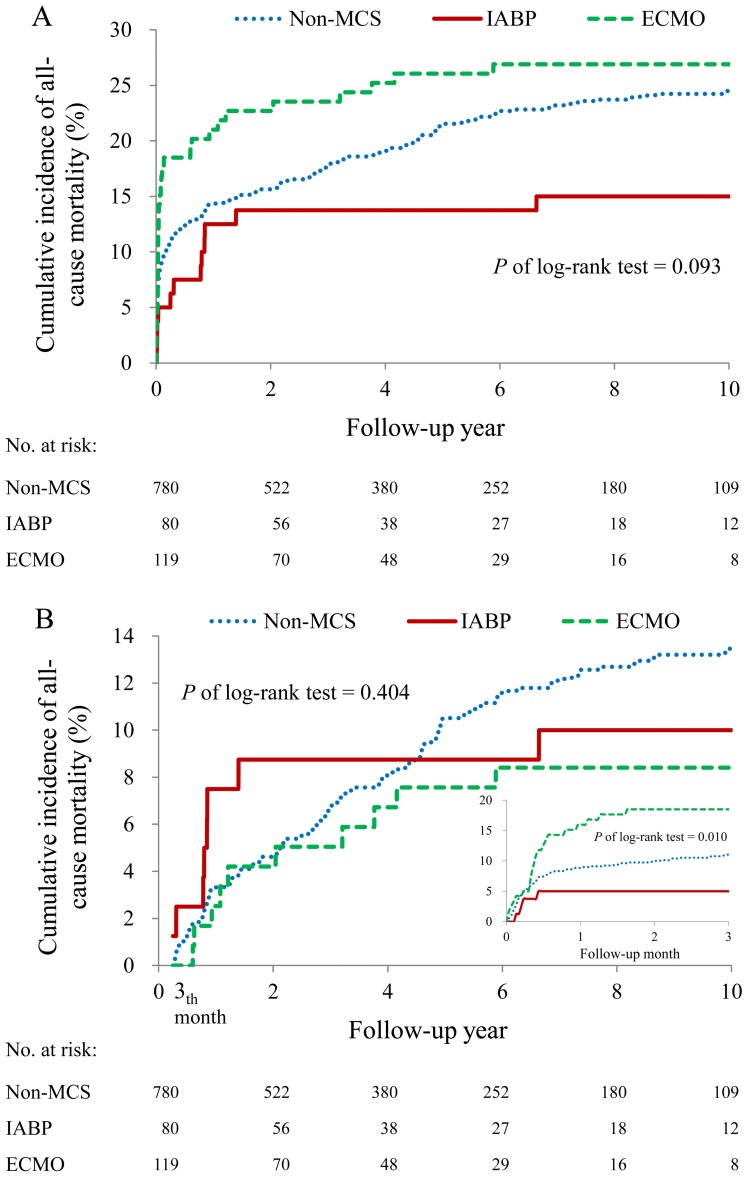

Overall, 91% (780/851) of the patients in the non-MCS group survived to discharge, 80% (80/99) in the IABP group and 61%(119/195) in ECMO group. During the 14-year observation period, the incidence of heart failure hospitalization was around 6~8% in the survivors, and no significant difference was noted between the three groups (p=0.742) (Table 3 and Figure S1). The incidence of cardiovascular death ranged from 10% to 22%, and the incidence in who received ECMO (21.8%) was higher than the rate in those who had no MCS or those who had IABP. The difference among the three groups was significant (hazard ratio [HR]: 3.88; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.93-5.12 for the ECMO vs. non-MCS group; HR: 2.74; 95% CI: 1.70-4.40 for ECMO vs. IABP group) (Table 3 and Figure 2A). When analyzing cardiovascular death in different periods, the difference appeared within 3 months (p<0.001) but it disappeared after 3 months (p=0.458) (Table 3 and Figure 2B). In addition, cardiovascular death majorly occurred within 3 months after discharge. In terms of all-cause mortality, the trend of differences between groups was similar as it in cardiovascular death (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the secondary outcomes, there were low incidence rates of long-term dialysis (0% to 1.3%), VT/VF (0% to 1.3%) and new stroke (0% to 3.6%). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in these secondary outcomes between the three groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Long-term outcomes of the survivors from acute myocarditis

| Variable | Number of events (%) | Adjusted hazard ratio and 95% CI‡ | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-MCS (n = 780) |

IABP (n = 80) |

ECMO (n = 119) |

IABP vs. Non-MCS | ECMO vs. non-MCS | ECMO vs. IABP | |||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |||||||

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||||||

| HF hospitalization* | 65 (8.3) | 5 (6.3) | 10 (8.4) | 0.58 (0.23, 1.46) | 0.248 | 0.69 (0.34, 1.40) | 0.303 | 1.18 (0.39, 3.56) | 0.767 | |||

| HF hospitalization within 3 months* | 20 (2.6) | 3 (3.8) | 2 (1.7) | 1.56 (0.48, 5.06) | 0.462 | 0.44 (0.09, 2.15) | 0.311 | 0.28 (0.05, 1.70) | 0.168 | |||

| HF hospitalization after 3 months* | 45 (5.8) | 2 (2.5) | 8 (6.7) | 0.27 (0.06, 1.20) | 0.085 | 1.18 (0.49, 2.82) | 0.716 | 4.43 (0.85, 23.19) | 0.078 | |||

| CV death | 101 (12.9) | 8 (10.0) | 26 (21.8) | 1.42 (0.90, 2.24) | 0.136 | 3.88 (2.93, 5.12) | <0.001 | 2.74 (1.70, 4.40) | <0.001 | |||

| CV death within 3 months | 32 (4.1) | 4 (5.0) | 19 (16.0) | 2.39 (1.41, 4.05) | 0.001 | 5.28 (3.79, 7.36) | <0.001 | 2.21 (1.31, 3.74) | 0.003 | |||

| CV death after 3 months | 69 (8.8) | 4 (5.0) | 7 (5.9) | 0.52 (0.19, 1.45) | 0.213 | 1.04 (0.50, 2.14) | 0.924 | 1.98 (0.60, 6.55) | 0.262 | |||

| All-cause mortality | 197 (25.3) | 12 (15.0) | 32 (26.9) | 0.53 (0.30, 0.97) | 0.038 | 1.42 (0.96, 2.10) | 0.084 | 2.65 (1.35, 5.20) | 0.005 | |||

| Mortality within 3 months | 86 (11.0) | 4 (5.0) | 22 (18.5) | 0.50 (0.18, 1.38) | 0.179 | 2.01 (1.22, 3.30) | 0.006 | 4.03 (1.37, 11.84) | 0.011 | |||

| Mortality after 3 months | 111 (14.2) | 8 (10.0) | 10 (8.4) | 0.53 (0.26, 1.11) | 0.090 | 0.87 (0.44, 1.73) | 0.690 | 1.64 (0.63, 4.26) | 0.310 | |||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Long-term dialysis | 10 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| VT/VF | 10 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | NA | NA | 0.24 (0.02-2.28) | 0.214 | NA | NA | |||

| Stroke | 28 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | NA | NA | 0.34 (0.04-2.66) | 0.303 | NA | NA | |||

Abbreviation: CV death: cardiovascular death; HF: heart failure, VT/VF: ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; MCS: mechanical circulation support;

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative incidence of cardiovascular death between three groups: non-MCS group, IABP group and ECMO group. (A) The cumulative incidence of cardiovascular death after index admission. (B) The cumulative incidence of cardiovascular death within 3 months and after 3 months after index admission. ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; MCS: mechanical circulatory support.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality between three groups: non-MCS group, IABP group and ECMO group. (A) The cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality after index admission. (B) The cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality within 3 months and after 3 months after index admission. ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; MCS: mechanical circulatory support.

Subgroup analysis between the patients without MCS but receiving inotropic agents and those with MCS

In total, 328 patients inotropic agents in the non-MCS group. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics, examinations, medications, intensive managements and resuscitation strategies between the patients without MCS but receiving inotropic agents and those with MCS (Table S3 and Table S4) as compared to the original groups (non-MCS, IABP and ECMO groups). With regards to in-hospital complications, there were still significant differences in VT/VF, acute renal failure and all-cause mortality (Table S5). With regards to long-term outcomes, the highest incidence of death was noted in the ECMO group, but no significant differences in heart failure hospitalization and other secondary outcomes between groups (Table S6, Figure S2).

Discussion

From this national cohort retrospective study, we though more severity still leads more risk of cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality in survivors from acute myocarditis. Although our result was different from it presented in pediatric population before, the severity of disease affect mortality within 3 months but did not thereafter.

In literature, the majority of patients with acute myocarditis are young males.17, 18 and this is consistent with our study, in which 59.3% of the patients were young males. According to the management of myocarditis, including medication or MCS, depends on the severity of the disease,19 and mechanical cardiopulmonary life support should be immediately used when circulatory insufficiency cannot be reversed with conventional medical treatment. Therefore, it is reasonable to classify the severity of the study population according to the usage of inotropic agents and the need of MCS. In this study, the prevalence of in-hospital complications related to acute myocarditis, such as VT/VF and acute renal failure, intensive management and resuscitation strategies were higher in the patients who received MCS, especially in those who need ECMO support. Such clinical presentations might further confirm the different degree of severity between groups divided by MCS.

There were several methods to identify acute myocarditis whose included EMB and CMR but they usually were limited in clinical practice. The use of EMB is limited due to a high complication rate, sampling error, sampling time, pathological interpretation and the need for specialist interpretation.3, 20, 21 In addition, the correlation between management strategies and biopsy results has been reported to be poor.8 In this study, EMB was performed in 7.1% of the patients. In terms of CMR, it is increasingly used as an alternative diagnostic tool due to its non-invasive nature and because it can reveal the whole cardiac structure.22 However, it is also limited by a long examination time and the clinical severity of acute myocarditis. CMR was performed in 4.5% of our patients, which may be because all of our patients required ICU.19 In addition, although the major etiology of acute myocarditis is viral infection,23 Kindermann I et al. concluded that neither Dallas's criteria nor the detection of a viral genome was a predictor of outcome24 and a study about biopsy-proven viral myocarditis also presented types of virus cannot predict long-term outcomes.25 Looking back our result that the primary outcomes from this population without an autoimmune disease were not affected by CMR, EMB or viral infection (Table S7).

The outcomes of acute myocarditis reported in the literature are recovery in nearly 50% of cases, more than 60% survival to discharge 5, 26 and 12-25% mortality or progression to end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy.12, 25 our results presented the similar results as it presented. The original concept, based mainly on pediatric population, is that if patients with this condition survive the critical few days for recovery of myocardial function, getting the required pharmacological and mechanical support, their long-term prognosis may be good.3 Some studies have reported that adult fulminant myocarditis has an excellent prognosis if patients receive adequate hemodynamic support, even though patients with fulminant myocarditis have more severe heart condition than those with acute myocarditis.7, 12 In addition, several studies have evaluated which factors influence the prognosis of patients with acute myocarditis. Although a study reported that initial left ventricular systolic function was a marker for prognosis regardless of the clinical pattern of disease onset, 18 but another study did not.25 In terms of initial clinical status, Stefan Grün et al. reported initial heart function class was a good predictor of incomplete recovery under multivariable regression analysis.25 As similar result phenomenon in our study, we presented the initial severity would affect the clinical outcomes after discharge, although we cannot take the ventricular function into analysis. The main strength of this nationwide case-control cohort study on acute myocarditis is the large number of patients (over 1000). In further subgroup analysis in different period after discharge, there were two interesting phenomenon. First, the incidences of cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality were higher when the severity of disease was more severe within 3 months after discharge but the trend disappeared thereafter. Second, the majority of death occurred within 3 months after discharge, but the event of heart failure hospitalization did not. In addition, cardiovascular death is the major component of all-cause mortality. Accordingly, we though the severity of disease would affect the short-term but not long-term mortality and major cause of cardiovascular would not be heart failure.

Study limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the accuracy of the diagnosis of acute myocarditis could not be verified. According to Dallas`s criteria,27 EMB is the gold standard method to make a diagnosis. However, its performance rate has been reported to be relatively low in clinical practice due to several limitations.3, 20, 21 In addition, patients with clinical presentations plus elevated troponin I/troponin T levels or abnormal electrocardiograms/echocardiograms19 can be classified in the clinical classification of 'probable acute myocarditis'.1 Therefore, in order to increase the accuracy of diagnosis, we recorded all possible management strategies of the patients with acute myocarditis, and selected those who needed intensive care. Furthermore, we excluded patients who had undergone coronary interventions and those with several comorbidities, which may affect the diagnosis. Thus, the diagnosis of acute myocarditis can be presumed to be highly accurate and the positive predictive value was around 96% in our validation.

Second, some factors that may affect long-term outcomes could not be obtained from the NHIRD, including biopsy results, the types of infecting virus, imaging results and left ventricular function. However, the aim of this study was to evaluate the correlation between in-hospital complications and long-term outcomes and the use of MCS. Thus, laboratory data or imaging results may have little influence on the conclusions. In addition, some previous studies have reported controversial results when evaluating examinations, including ventricular function and types of virus, for acute myocarditis.21, 23,25 Third, the severity of disease could not be assessed by ICD-9-CM code, and clinical hemodynamic data were not available to confirm the severity. Finally, the data used in this study came from the National Health Insurance system of Taiwan, which includes a large number of patients, and the complete follow-up should counterbalance the inherent study weaknesses, and thereby ameliorate some of the limitations.

Conclusion

The incidence of heart failure hospitalization was low in long-term follow-up, and it was not significantly correlated with the type of MCS, while the risks of cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality were the highest in patients needed ECMO. Accordingly, cardiovascular death is the leading cause of all-cause mortality and the risk of cardiovascular mortality in short-term period was closely associated with the severity of acute myocarditis but not long-term period. Therefore, be attention to the cardiovascular death within 3 months after index admission and it is an important issue about preventing sudden cardiac death, in acute myocarditis patient needed MCS.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Hsing-Fen Lin for the statistical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG6E0171 and CORPG6D0161).

References

- 1.Sagar S, Liu PP, Cooper LT Jr. Myocarditis. Lancet. 2012;379:738–747. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60648-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nugent AW, Daubeney PE, Chondros P. et al. The epidemiology of childhood cardiomyopathy in australia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1639–1646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amabile N, Fraisse A, Bouvenot J, Chetaille P, Ovaert C. Outcome of acute fulminant myocarditis in children. Heart. 2006;92:1269–1273. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.078402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maisch B, Ruppert V, Pankuweit S. Management of fulminant myocarditis: A diagnosis in search of its etiology but with therapeutic options. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2014;11:166–177. doi: 10.1007/s11897-014-0196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajagopal SK, Almond CS, Laussen PC, Rycus PT, Wypij D, Thiagarajan RR. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for the support of infants, children, and young adults with acute myocarditis: A review of the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:382–387. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181bc8293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nahum E, Dagan O, Lev A. et al. Favorable outcome of pediatric fulminant myocarditis supported by extracorporeal membranous oxygenation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:1059–1063. doi: 10.1007/s00246-010-9765-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mody KP, Takayama H, Landes E, Yuzefpolskaya M, Colombo PC, Naka Y. et al. Acute mechanical circulatory support for fulminant myocarditis complicated by cardiogenic shock. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2014;7:156–164. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9521-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan BW, Bohn DJ, Atz AM. et al. Mechanical circulatory support for the treatment of children with acute fulminant myocarditis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:440–448. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.115243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyake CY, Teele SA, Chen L. et al. In-hospital arrhythmia development and outcomes in pediatric patients with acute myocarditis. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe T, Tsuda E, Miyazaki A, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Yamada O. Clinical characteristics and long-term outcome of acute myocarditis in children. Heart Vessels. 2013;28:632–638. doi: 10.1007/s00380-012-0296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mason JW. Myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy: An inflammatory link. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy RE 3rd, Boehmer JP, Hruban RH. et al. Long-term outcome of fulminant myocarditis as compared with acute (nonfulminant) myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:690–695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003093421003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sankar J, Khalil S, Jeeva Sankar M, Kumar D, Dubey N. Short-term outcomes of acute fulminant myocarditis in children. Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;32:885–890. doi: 10.1007/s00246-011-0007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karen A, Hicks HM, The Standardized Data Collection for Cardiovascular Trials Initiative Standardized definitions for end point events in cardiovascular trials. 2010.

- 15.Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, Nilasena DS, Radford MJ, Gage BF. Accuracy of icd-9-cm codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care. 2005;43:480–485. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160417.39497.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q, Glynn RJ, Dreyer NA, Liu J, Mogun H, Setoguchi S. Validity of claims-based definitions of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in medicare patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:700–708. doi: 10.1002/pds.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cocker MS, Abdel-Aty H, Strohm O, Friedrich MG. Age and gender effects on the extent of myocardial involvement in acute myocarditis: A cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Heart. 2009;95:1925–1930. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.164061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anzini M, Merlo M, Sabbadini G, Barbati G, Finocchiaro G, Pinamonti B. et al. Long-term evolution and prognostic stratification of biopsy-proven active myocarditis. Circulation. 2013;128:2384–2394. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caforio AL, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, Basso C, Gimeno-Blanes J, Felix SB. et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: A position statement of the european society of cardiology working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2636–2648. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht210. 2648a-2648d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shanes JG, Ghali J, Billingham ME, Errans VJ, Fenoglio JJ, Edwards WD. et al. Interobserver variability in the pathologic interpretation of endomyocardial biopsy results. Circulation. 1987;75:401–405. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baughman KL. Diagnosis of myocarditis: Death of dallas criteria. Circulation. 2006;113:593–595. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.589663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yilmaz A, Ferreira V, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Neubauer S, Sechtem U. Role of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (cmr) in the diagnosis of acute and chronic myocarditis. Heart Fail Rev. 2013;18:747–760. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9356-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blauwet LA, Cooper LT. Myocarditis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;52:274–288. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kindermann I, Kindermann M, Kandolf R, Klingel K, Bultmann B, Muller T. et al. Predictors of outcome in patients with suspected myocarditis. Circulation. 2008;118:639–648. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grün S, Schumm J, Greulich S, Wagner A, Schneider S, Bruder O. et al. Long-term follow-up of biopsy-proven viral myocarditis: predictors of mortality and incomplete recovery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1604–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirabel M, Luyt CE, Leprince P, Trouillet JL, Leger P, Pavie A. et al. Outcomes, long-term quality of life, and psychologic assessment of fulminant myocarditis patients rescued by mechanical circulatory support. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1029–1035. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820ead45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aretz HT, Billingham ME, Edwards WD, Factor SM, Fallon JT, Fenoglio JJ Jr. et al. Myocarditis. A histopathologic definition and classification. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol. 1987;1:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.