Abstract

Endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 (ESM1) is a major prognostic marker of several tumor types, but its value as a marker for prostate cancer is unknown. The purpose of the present study was to measure the relationship of ESM1 expression with androgen receptor (AR) expression and with Gleason score in human prostate carcinoma tissue. Expression of ESM1 and AR were determined by immunohistochemical staining of prostate tissues from healthy individuals and patients with prostate cancer. The results showed that ESM1 expression was significantly higher in prostate tumor tissues than in normal prostate tissues (p < 0.01), and that ESM1 expression in prostate tumor tissue correlated with Gleason score (p < 0.016) and Gleason grade (p < 0.013). ESM1 expression was also greater in prostate tissues with higher Gleason score and Gleason grade (p < 0.001 for both comparisons), and also correlated with AR expression (R = 0.727, p < 0.001). In conclusion, our results demonstrated that ESM1 should be considered as a marker for the diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Keywords: Human prostate cancer, Gleason score, Endothelial cell specific molecule 1, Androgen Receptor.

Introduction

Prostate carcinoma (PC) is one of the most prevalent cancers world-wide, and is the second-most diagnosed cancer in men 1. Certain dietary factors, lifestyle factors, and prostate cancer-susceptibility alleles, such as specific alleles of the androgen receptor (AR), increase the risk for development of PC 2. The Gleason score of PC is a well-established prognostic indicator 3, and clinicians often use the Gleason score to estimate the response to a specific therapy, such as radiotherapy and/or surgery. The discovery of additional biomarkers by gene expression profiling or testing for DNA abnormalities may help to better predict prognosis and provide value beyond the Gleason score 3.

Endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 (ESM1), also known as endocan, is secreted into the blood as a 50 kDa soluble proteoglycan that has 165 amino acids as a mature polypeptide. Lassalle and colleagues originally cloned ESM1 from a human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) cDNA library 4. In normal human tissues, ESM1 is selectively expressed in actively proliferative and neogeneic tissues and cells, such as glandular tissues, endothelial cells of neovasculature tissues, the bronchial epithelium, and germinal centers of lymph nodes 5. Inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1), unregulated ESM1 mRNA, and this upregulation is associated with tumor growth and angiogenesis during tumor progression 4, 6, 7. ESM1 also promotes tumor growth in a mouse model with human tumor xenografts 7, and its expression correlates with the development of lung, renal, and breast cancers 8-11.

More generally, ESM1 is regarded as a marker of angiogenesis. ESM1-mediated promotion of microvessel density correlates with microscopic venous invasion and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma 12. The circulating level of ESM1 is also markedly increased in the serum of patients with advanced lung cancer 7, and ESM1 expression is associated with tumor prognosis, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Thus, ESM1 may act as a marker for angiogenesis or oncogenesis, and could be regarded as a candidate gene for identification of inflammatory tissue, neoplasia, metastasis, and tumor development 5. The present study examines the relationships between ESM1 expression, Gleason score, and AR expression in human prostate carcinoma tissues and prostate tissue of healthy individuals to assess its potential as a marker for diagnosis and prediction of prognosis in patients with PC.

Materials and Methods

Human prostate cancer tissues array

The tissue microarrays (TMAs) from a wide range of prostate tissues were assembled using a microarray with human prostate cancer specimens and normal prostate tissue (PR803b; US Biomax, Inc). The prostate patient data and clinicopathological characteristics, including age, sex, tumor stage, tumor grade, Gleason grade, and Gleason score, were obtained from medical records. Prostate tissues from 71 patients were examined by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for ESM1 and AR. Digital images were acquired from 4-μm thick sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and from immunostained TMA slides using the Pannoramic MIDI II System (Budapest, Hungary).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Staining

IHC staining was performed on sections of paraffin-embedded tissues. All formalin-fixed prostate tissues were embedded in paraffin, and 5-µm sections were prepared. Sections were processed by heating at 70℃ in an oven for 30 min, dewaxing with xylene and alcohol (2 cycles, 10 min each), deparaffinization, and rehydration. Then endogenous peroxidase was blocked for 20 min in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in water. The slides were then treated for antigen retrieval in a citrate buffer (pH 6) for 10 min at 95°C (DAKO PT Link, Glostrup, Denmark). The primary antibodies were anti-ESM1 (Abnova, H00011082-M02) and anti-AR antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-815). Samples were incubated with DAKO envision that contained horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit, goat anti-mouse, or rabbit anti-goat antibodies (DAKO Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) for 30 min. The slides were visualized using a diaminobenzidine solution (DAB+; DAKO kit).

Immunoreactivity Scoring

The intensity of IHC staining was quantified using an immunoreactivity score (IRS). The IRS is a function of the percentage of stained cells and of the staining intensity of immunoreactive cells. The percentage score was 0 when there were no positive cells; 1 or 2 when there were 1 to 25% positive cells, 3 when there were 25 to 50% positive cells; 4 when there were 50 to 90% positive cells, and 5 when there more than 90% positive cells. The intensity score was 3 for weak cell staining; 4 for moderate cell staining; and 5 for strong cell staining. The two scores were added, so the final score ranged from 3 to 5. Median scores were used for data analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using the SPSS statistical software program (standard version 18.0; SPSS,Chicago, USA). Correlation between variables was evaluated by Spearman rank correlation coefficients. p < 0.01 denotes the presence of a statistically significant difference.

Results

Relationship of ESM1 expression with clinicopathological characteristics of prostate cancer patients

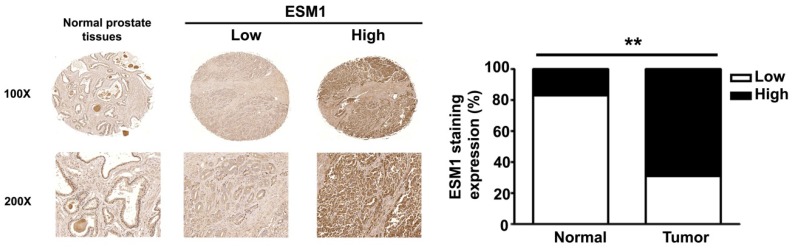

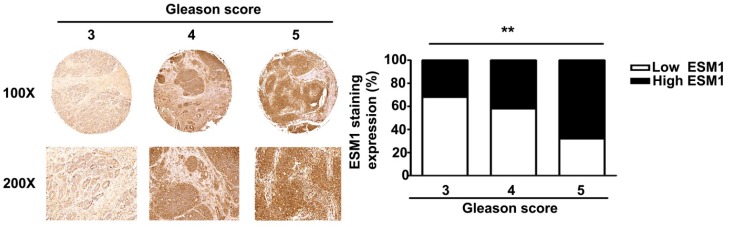

Immunohistochemical staining of prostate tissues from humans indicates that ESM1 has higher expression in cancerous than normal prostate tissues (Fig 1). Table 1 summarizes the relationships between ESM-1 expression and clinicopathological parameters of prostate cancer patients. Age and tumor stage were unrelated to ESM1 expression. However, ESM1 expression was significantly greater in the prostate tumors of patients with higher Gleason grades (p = 0.013) and Gleason scores (p = 0.016) (Fig 2, Table 1).

Figure 1.

ESM1 expression in normal and cancerous of human prostate tissues. Representative IHC light microscopy images showing the expression of ESM1 in normal prostate tissues and in prostate carcinoma tissues with low and high expression of ESM1. The expression of ESM1 was quantified by a pathologist. The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01). Scale bars = 100 μm.

Table 1.

Correlation between ESM1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics of prostate cancer patients

| Characteristic | Number of patients (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM1 staining | |||

| Negative | Positive | ||

| Total number of patients | 37 (52.1) | 34 (47.9) | |

| Age (year) | |||

| <67 | 15 (53.6) | 13(46.4) | 0.518 |

| ≧67 | 22 (51.2) | 21 (48.8) | |

| Tumor Stage | |||

| I+II | 21 (56.8) | 16(43.2) | 0.238 |

| III+IV | 14 (41.2) | 20 (58.8) | |

| Gleason Grade | |||

| 3 | 15 (68.2) | 7 (31.8) | 0.013 |

| 4 | 14 (58.3) | 10 (41.7) | |

| 5 | 8 (32.0) | 17 (68.0) | |

| Gleason Score | |||

| 3 | 13 (68.4) | 6 (31.6) | 0.016 |

| 4 | 15 (60) | 10 (40) | |

| 5 | 9 (33.3) | 18 (66.7) | |

Figure 2.

Gleason score and ESM1 expression in human prostate carcinomas. ESM1 was determined by IHC staining and light microscopy. Gleason score and ESM1 expression were quantified by a pathologist. The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01). Scale bars = 100 μm

Correlation between levels of ESM1 and AR in prostate cancer patients

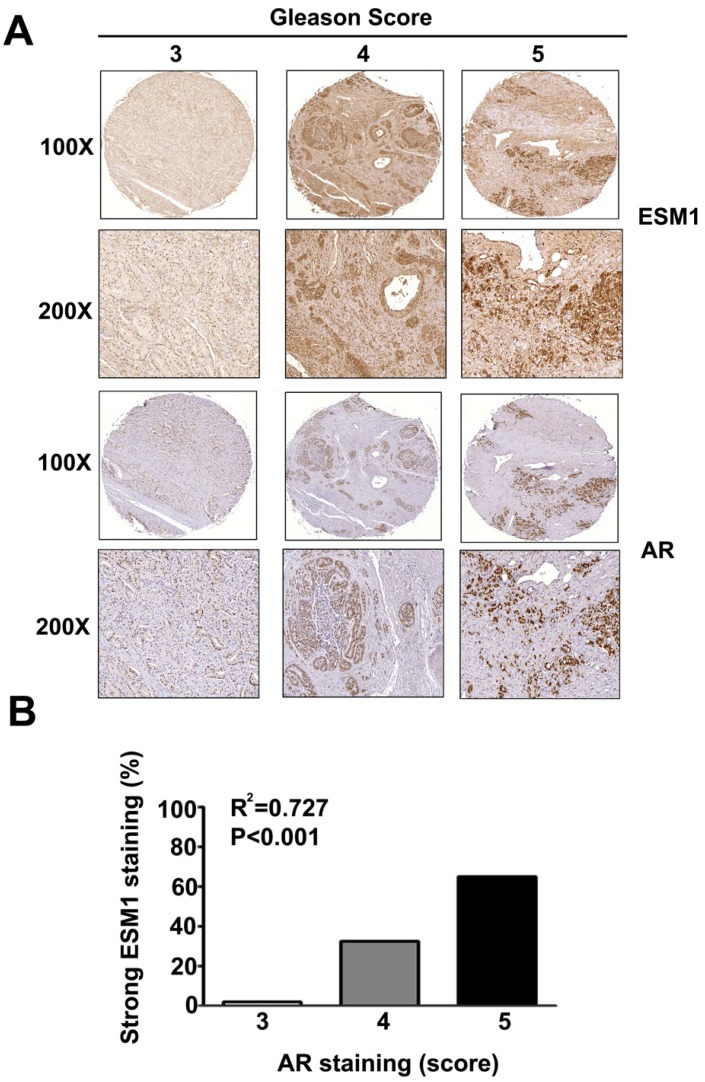

Figure 3A shows representative IHC images of ESM1 and AR expression in prostate cancer patients. Quantitation of these results shows that expression of ESM1 and AR were significantly higher in patients with Gleason scores of 5 than in those with Gleason scores of 3 or 4 (p < 0.001). Analysis of the relationship between ESM1 and AR expression in prostate cancer tissues indicated a positive correlation (p < 0.001; Fig. 3B). This, our findings indicate that ESM1 expression correlates with Gleason score, and could therefore be a useful marker for the diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Figure 3.

Relationship of ESM1 expression and AR expression with Gleason score in human prostate carcinomas. (A) Human prostate carcinoma tissues were stained for ESM1 and AR by IHC and visulaized by light microscopy. Gleason score, and expression of ESM-1 and AR were determined by a pathologist. (B) Correlation between the expression of ESM1 and AR The difference was highly statistically significant (p < 0.001). Scale bars = 100 μm

Discussion

The present study used IHC analysis of prostate tissue to determine the relationship of ESM1 expression with Gleason grade and score and with AR expression. The results show that ESM1 expression correlates with Gleason score and grade and with AR expression in human prostate cancer. Thus, ESM1 may be useful as a prognostic indicator, by providing value beyond the established Gleason grade and score.

The Gleason grading system is the main method used to stage prostate cancer 4. This system mainly considers the histological pattern of cells in H&E-stained sections of prostate tissue. The strength of the Gleason grading system is that it is useful for follow-up of a large variety of patients. The Gleason system has five grades (1 to 5) based on the morphology of the most common cell type, and another five grades (1 to 5) based on the morphology of the second-most common cell type. Thus the total histological score ranges from 2 to 10. The common practice is to consider a Gleason score of 2-4 as well-differentiated carcinoma, 5-7 as moderately differentiated carcinoma, and 8-10 as poorly differentiated carcinoma. However, a Gleason score of 7 usually has characteristics of high-grade carcinoma. Our findings indicate that ESM1 expression positive correlates with Gleason score.

The AR has a critical role in regulation of the proliferation of androgen-refractory prostate cancer cells, even in the absence of androgens 13. Many somatic alterations of the AR gene are present in human prostate carcinoma tissue, especially in patients who progress despite hormonal treatment. AR gene amplification can develop during androgen deprivation therapy, and promote tumor cell growth in the presence of low androgen concentrations 14. Increased expression of the wild-type AR gene appears to play a key role when prostate carcinoma growth occurs in the presence of androgen deprivation therapy 15. In the absence of AR mutations, androgen-independent prostate cancer may progress through activation of ligand-independent AR signaling pathways 16, 17. The present study shows that the AR protein is overexpressed in human prostate cancer, and its expression correlates with Gleason score and expression of ESM1.

ESM1 is a product of endothelial cells, is highly regulated by VEGF, and its expression increases significantly during the switch from dormant to angiogenic tumors in vitro and in vivo 18-20. In addition, a study of mouse xenograft models of breast cancer, glioblastoma, osteosarcoma, and liposarcoma reported that ESM1 expression correlates with conversion of dormant tumors to exponentially growing tumors 21. Knockdown of ESM1 affected cell proliferation and invasion through downregulation of NF-κB, EMT and the upregulation of PTEN in human colorectal cancer 22. Recent reports showed that deletion of ESM1 reduces NGFR induced tumor growth and metastases in oral SCC cells in vitro and in vivo, providing NGFR-enhanced metastatic capacity of oral SCC cells is dependent on ESM1 expression 23. Large scale studies of human gene expression showed that ESM1 expression correlates with the expression of angiogenic molecules, such as VEGF, VEGFR, and c-met, in various types of cancers 20. IHC staining indicates that human ESM1 is remarkably overexpressed in the cytoplasm of endothelial cells of tumor vessels in various human cancers, such as lung cancer 7, 18, brain cancer 19, colon cancer 24, liver cancer 12, and clear cell carcinoma of the kidney 25, 26. A study of glioblastoma indicated that ESM1 is present in endothelial cells within and at the margins of the brain tumor, and its expression correlates with grade and abnormal neoangiogenesis in these tumors 19. Another study reported that ESM1 is a potential biomarker in tissues from patients with renal cancer; in particular IHC staining indicated ESM1 was present in the cytoplasm of endothelial cells in clear cell renal carcinoma, and was also present in small and large intra-tumor vessels 24. Biomarkers can contribute to the clinical diagnosis of cancers. During clinical trials, biomarkers allow stratification of patient populations according to disease progression, and the monitoring of drug safety and efficacy. IHC staining of ESM1 is a simple, inexpensive, and reliable method for the analysis of tumor tissues, and is effective in guiding the treatment of hypervascular cancers. Previous studies indicated that ESM1 could be considered as a promising biomarker to assess the prognosis of tumors in the breast 8, lung 11, brain 19, ovary 27, kidney 24, 28, and liver 12. We found that ESM1 expression correlates with Gleason grade/score and with AR expression in prostate carcinoma tissue, so ESM1 should also be considered as a biomarker for diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Chung Shan Medical University and Cheng-Ching General Hospital, Taiwan (CSMU-CCGH-104-01).

Abbreviations

- AR

androgen receptor

- ESM1

endothelial cell-specific molecule 1

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IHC

immunohistochemical

- IRS

immunoreactivity score

- PC

prostate cancer

- TMA

Tissue microarray.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson WG, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB. Prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:366–381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humphrey PA. Gleason grading and prognostic factors in carcinoma of the prostate. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:292–306. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lassalle P, Molet S, Janin A, Heyden JV, Tavernier J. et al. ESM-1 is a novel human endothelial cell-specific molecule expressed in lung and regulated by cytokines. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20458–20464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang SM, Zuo L, Zhou Q, Gui SY, Shi R. et al. Expression and distribution of endocan in human tissues. Biotech Histochem. 2012;87:172–178. doi: 10.3109/10520295.2011.577754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerritsen ME, Tomlinson JE, Zlot C, Ziman M, Hwang S. Using gene expression profiling to identify the molecular basis of the synergistic actions of hepatocyte growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:595–610. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scherpereel A, Gentina T, Grigoriu B, Senechal S, Janin A. et al. Overexpression of endocan induces tumor formation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6084–6089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van 't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA. et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–536. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenburg ME, Liou LS, Gerry NP, Frampton GM, Cohen HT. et al. Previously unidentified changes in renal cell carcinoma gene expression identified by parametric analysis of microarray data. BMC Cancer. 2003;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amatschek S, Koenig U, Auer H, Steinlein P, Pacher M. et al. Tissue-wide expression profiling using cDNA subtraction and microarrays to identify tumor-specific genes. Cancer Res. 2004;64:844–856. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borczuk AC, Shah L, Pearson GD, Walter KL, Wang L. et al. Molecular signatures in biopsy specimens of lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:167–174. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-066OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang GW, Tao YM, Ding X. Endocan expression correlated with poor survival in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:389–394. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zegarra-Moro OL, Schmidt LJ, Huang H, Tindall DJ. Disruption of androgen receptor function inhibits proliferation of androgen-refractory prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1008–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visakorpi T, Hyytinen E, Koivisto P, Tanner M, Keinanen R. et al. In vivo amplification of the androgen receptor gene and progression of human prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 1995;9:401–406. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koivisto P, Kononen J, Palmberg C, Tammela T, Hyytinen E. et al. Androgen receptor gene amplification: a possible molecular mechanism for androgen deprivation therapy failure in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:314–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadar MD, Gleave ME. Ligand-independent activation of the androgen receptor by the differentiation agent butyrate in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5825–5831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craft N, Shostak Y, Carey M, Sawyers CL. A mechanism for hormone-independent prostate cancer through modulation of androgen receptor signaling by the HER-2/neu tyrosine kinase. Nat Med. 1999;5:280–285. doi: 10.1038/6495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grigoriu BD, Depontieu F, Scherpereel A, Gourcerol D, Devos P. et al. Endocan expression and relationship with survival in human non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4575–4582. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maurage CA, Adam E, Mineo JF, Sarrazin S, Debunne M. et al. Endocan expression and localization in human glioblastomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:633–641. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a52a7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarrazin S, Adam E, Lyon M, Depontieu F, Motte V. et al. Endocan or endothelial cell specific molecule-1 (ESM-1): a potential novel endothelial cell marker and a new target for cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1765:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almog N, Ma L, Raychowdhury R, Schwager C, Erber R. et al. Transcriptional switch of dormant tumors to fast-growing angiogenic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2009;69:836–844. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang YH, Ji NY, Han SR, Lee CI, Kim JW. et al. ESM-1 regulates cell growth and metastatic process through activation of NF-kappaB in colorectal cancer. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1940–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen C, Shin JH, Eggold JT, Chung MK, Zhang LH. et al. ESM1 mediates NGFR-induced invasion and metastasis in murine oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:70738–70749. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuo L, Zhang SM, Hu RL, Zhu HQ, Zhou Q. et al. Correlation between expression and differentiation of endocan in colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4562–4568. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leroy X, Aubert S, Zini L, Franquet H, Kervoaze G. et al. Vascular endocan (ESM-1) is markedly overexpressed in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2010;56:180–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rennel E, Mellberg S, Dimberg A, Petersson L, Botling J. et al. Endocan is a VEGF-A and PI3K regulated gene with increased expression in human renal cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buckanovich RJ, Sasaroli D, O'Brien-Jenkins A, Botbyl J, Hammond R. et al. Tumor vascular proteins as biomarkers in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:852–861. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cifola I, Spinelli R, Beltrame L, Peano C, Fasoli E. et al. Genome-wide screening of copy number alterations and LOH events in renal cell carcinomas and integration with gene expression profile. Mol Cancer. 2008;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]