Abstract

Background: Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are involved in tumor progression and drug resistance. We hypothesized that variants in CSC marker genes influence treatment outcomes in prostate cancer.

Methods: Ten potentially functional single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in seven prostate CSC marker genes, TACSTD2, PROM1, ITGA2, POU5F1, EZH2, PSCA, and CD44, were selected for analysis of their association with disease recurrence by Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression in a cohort of 320 patients with localized prostate cancer receiving radical prostatectomy.

Results: We identified one independent SNP, rs2394882, in POU5F1 that was associated with prostate cancer recurrence (hazard ratio 0.32, 95% confidence interval 0.14-0.71, P = 0.005) after adjustment for known clinical predictors. Further in silico functional analyses revealed that rs2394882 affects POU5F1 expression, which in turn is significantly correlated with prostate cancer aggressiveness and patient prognosis.

Conclusion: Our results suggest that rs2394882 is prognostically relevant in prostate cancer, possibly by modulating the expression of the CSC gene POU5F1.

Keywords: prostate cancer, radical prostatectomy, recurrence, cancer stem cell, single nucleotide polymorphism, POU5F1

Introduction

Prostate cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers in men. Treatment options for prostate cancer strongly depend on tumor risk assessment; the most commonly used options are radical prostatectomy (RP), radiation therapy, endocrine therapy, and chemotherapy with docetaxel 1, 2. Most patients with prostate cancer respond initially to treatment; however, in numerous cases, eventual recurrence and progression to highly aggressive castration-resistant prostate cancer are observed. Therefore, the identification of biomarkers for diagnosis, monitoring, and therapy of prostate cancer is urgently needed.

Drug resistance and recurrence in prostate cancer may be, at least in part, explained by the existence of cancer stem cells (CSCs); however, this explanation remains controversial. CSCs are a rare subset of the cancer cell population that are capable of self-renewal, giving rise to a hierarchy of proliferative and differentiated tumor cells and leading to tumor progression and recurrence 3, 4. Putative prostate CSCs were first isolated from human prostate cancer biopsies with CD44+/α2β1 integrinhigh/CD133+ markers 5. These isolated cells exhibit a high potential for self-renewal, are capable of differentiating into heterogeneous cancer cells, and possess the ability to initiate tumor development in immunodeficient mice 6. Moreover, prostate CSCs are slow growing and highly resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy targeting actively dividing cancer cells 7. These findings suggest a link between CSCs and disease recurrence in patients with prostate cancer. In the present study, we selected 10 potentially functional single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in prostate CSC marker genes and evaluated their association with disease recurrence in patients with localized prostate cancer receiving RP.

Patients and Methods

Patient recruitment and data collection

In total, 320 patients with localized prostate cancer undergoing initial treatment with RP at the National Taiwan University Hospital, E-Da Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, and Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital were recruited, as described previously 8-12. Patient baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes were collected from their medical records. Biochemical recurrence (BCR) was defined as two consecutive prostate-specific antigen (PSA) values of 0.2 ng/mL or more after RP 9, 13. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital in accordance with the approval procedures.

SNP selection and genotyping

A unique prostate-specific stem cell marker has not yet been identified; however, certain stemness markers that are generally present in stem cells are also expressed in prostate stem cells, including tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 2 (TACSTD2), prominin 1 (PROM1, also termed CD133), integrin subunit alpha 2 (ITGA2), POU class 5 homeobox 1 (POU5F1, also termed OCT4), enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit (EZH2), prostate stem cell antigen (PSCA), and CD44 14-16. We used the Functional Analysis and Selection Tool for Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (FASTSNP) 17 to predict the functional effects of SNPs in these prostate cancer stem cell marker genes and to estimate their risk scores. SNPs with a risk score lower than 2 and a minor allele frequency of less than 0.02 in the HapMap Han Chinese in Beijing population 18 were excluded, leaving 10 potentially functional SNPs for analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and stored at -80°C until analysis. Genotyping was carried out at the National Center for Genome Medicine, Taiwan, using the Agena Bioscience iPLEX matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass-spectrometry technology, as described previously 9. The genotyping concordance rate among 54 blinded duplicated quality-control samples was 100%. All SNPs conformed to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.05) and were included for further statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis

Patient clinicopathologic characteristics were summarized as the numbers and percentages of patients. The association of individual SNPs and clinicopathologic characteristics with BCR was assessed using log-rank tests. Multivariate Cox regression was carried out to determine the interdependency of individual SNPs with known prognostic factors such as age, PSA at diagnosis, pathologic Gleason score, pathologic stage, surgical margin, and lymph node metastasis 19, 20. Trends in POU5F1 gene expression among genotypes at rs2394882 or prostate tissues were analyzed by Spearman correlation. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 22.0.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used for other statistical analyses. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Bioinformatics analysis

The association of rs2394882 with POU5F1 expression was evaluated using mRNA data from lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from 270 HapMap individuals from four worldwide populations 18. The GI_42560247-A probe was used for POU5F1 expression analysis. Publicly available transcriptome data from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Prostate Oncogenome 21, Lapointe et al. 22, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset for prostate adenocarcinoma 23, and the SurvExpress database 24 were utilized to analyze POU5F1 gene expression and clinical outcomes.

Results

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the 320 patients with localized prostate cancer after RP and their associations with BCR are presented in Table S1. One hundred and sixteen (36.3%) patients exhibited BCR during the median follow-up of 26 months, and the median BCR-free survival was 53 months. BCR was significantly related to PSA varieties at diagnosis, as well as to pathologic Gleason score, stage, surgical margin, and lymph node metastasis (all P < 0.001).

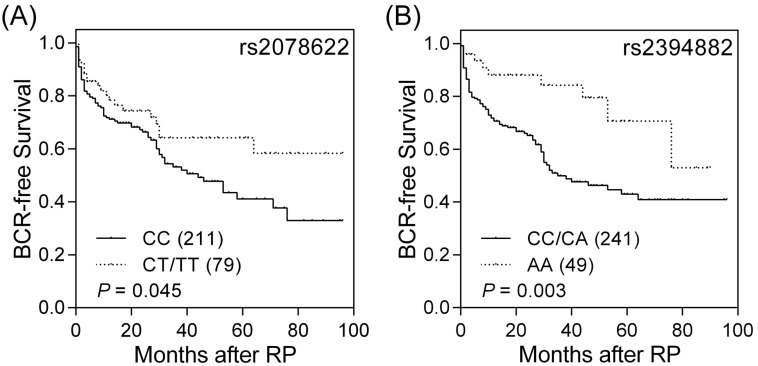

Among the 10 genotyped potentially functional SNPs in the seven prostate CSC marker genes, TACSTD2, PROM1, ITGA2, POU5F1, EZH2, PSCA, and CD44, PROM1 rs2078622, and POU5F1 rs2394882 were significantly associated with BCR (log-rank P ≤ 0.045, Table 1 and Figure 1). The effects of PROM1 rs2078622 and POU5F1 rs2394882 on BCR in patients with prostate cancer treated with RP were further assessed by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses (Table 2). Patients who carried the homozygous variant AA genotype of POU5F1 rs2394882 had a significantly decreased risk of recurrence (hazard ratio 0.37, 95% confidence interval 0.19-0.74, P = 0.005). This association remained significant (P = 0.005) after adjustment for known predictors, including age, PSA at diagnosis, pathologic Gleason score, pathologic stage, surgical margin, and lymph node metastasis. However, PROM1 rs2078622 did not reach significance in multivariate Cox regression analysis. These results indicated that, in addition to clinical features, POU5F1 rs2394882 represents an independent prognostic factor for prostate cancer recurrence after RP.

Table 1.

Genotyped SNPs and the P values of their association with BCR in patients with localized prostate cancer treated with RP

| Gene | SNP ID | Chromosome | Position | Possible Functional Effects | Log-rank P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive | Dominant | Recessive | |||||

| TACSTD2 | rs14008 | 1 | 59042181 | Missense (conservative); Splicing regulation | 0.809 | 0.811 | 0.909 |

| PROM1 | rs6449209 | 4 | 15982166 | Splicing site | 0.924 | 0.932 | 0.803 |

| PROM1 | rs2078622 | 4 | 16037352 | Splicing site | 0.072 | 0.045 | ‒ |

| ITGA2 | rs1062535 | 5 | 52351413 | Sense/synonymous; Splicing regulation | 0.279 | 0.642 | 0.101 |

| ITGA2 | rs1801106 | 5 | 52358757 | Splicing site | 0.646 | 0.646 | ‒ |

| POU5F1 | rs2394882 | 6 | 31132649 | Splicing site | 0.012 | 0.184 | 0.003 |

| EZH2 | rs2302427 | 7 | 148525904 | Missense (conservative) | 0.321 | 0.160 | 0.555 |

| PSCA | rs2294008 | 8 | 143761931 | Missense (conservative); Splicing regulation | 0.181 | 0.217 | 0.344 |

| PSCA | rs3736001 | 8 | 143762807 | Missense (conservative); Splicing regulation | 0.057 | 0.090 | 0.158 |

| CD44 | rs1071695 | 11 | 35201842 | Sense/synonymous; Splicing regulation | 0.905 | 0.934 | 0.656 |

Abbreviations: SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; BCR, biochemical recurrence; RP, radical prostatectomy.

‒, not calculated due to insufficient numbers.

P < 0.05 are in boldface.

Figure 1.

Impact of PROM1 rs2078622 and POU5F1 rs2394882 on prostate cancer prognosis. Kaplan-Meier analysis of BCR after RP, stratified by genotypes at (A) PROM1 rs2078622 and (B) POU5F1 rs2394882. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of patients.

Table 2.

Association of PROM1 rs2078622 and POU5F1 rs2394882 with BCR after RP

| Gene SNP | n | BCR | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| PROM1 rs2078622 | ||||||

| CC | 211 | 82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| CT | 74 | 20 | 0.61 (0.37-0.99) | 0.044 | 0.76 (0.44-1.30) | 0.310 |

| TT | 5 | 2 | 0.93 (0.23-3.79) | 0.920 | 0.36 (0.05-2.69) | 0.319 |

| CT/TT vs. CC | 0.63 (0.39-1.00) | 0.051 | 0.72 (0.42-1.22) | 0.216 | ||

| Trend | 0.68 (0.44-1.05) | 0.078 | 0.72 (0.44-1.15) | 0.168 | ||

| POU5F1 rs2394882 | ||||||

| CC | 109 | 43 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| CA | 132 | 51 | 0.96 (0.64-1.44) | 0.832 | 1.00 (0.62-1.61) | 0.988 |

| AA | 49 | 9 | 0.36 (0.18-0.75) | 0.006 | 0.32 (0.14-0.73) | 0.007 |

| CA/AA vs. CC | 0.77 (0.52-1.14) | 0.192 | 0.76 (0.48-1.20) | 0.237 | ||

| AA vs. CC/CA | 0.37 (0.19-0.74) | 0.005 | 0.32 (0.14-0.71) | 0.005 | ||

| Trend | 0.71 (0.54-0.93) | 0.014 | 0.68 (0.49-0.93) | 0.018 | ||

Abbreviations: BCR, biochemical recurrence; RP, radical prostatectomy; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

*Adjusted by age, PSA at diagnosis, pathologic Gleason score, pathologic stage, surgical margin, and lymph node metastasis.

P < 0.05 are in boldface.

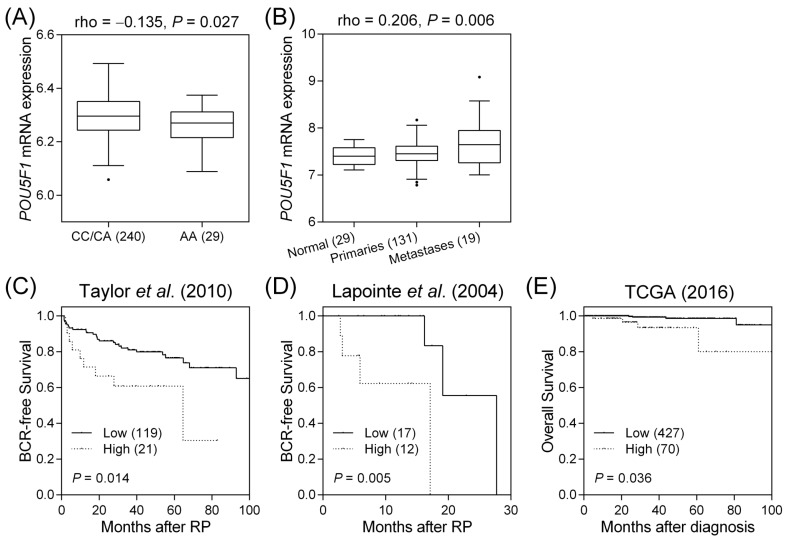

Next, we investigated whether rs2394882 affects POU5F1 expression using the HapMap data. Individuals carrying a homozygous for the protective A allele of rs2394882 showed lower POU5F1 expression than those carrying a risk allele C (P = 0.027, Figure 2A). To assess the effect of POU5F1 on prostate cancer progression, we conducted a comprehensive in silico evaluation of publicly available MSKCC Prostate Oncogenome Project data. POU5F1 expression tended to be higher in more aggressive forms of prostate cancer (P = 0.006, Figure 2B). Furthermore, a risk score was calculated for each patient based on the Cox regression coefficient of POU5F1 expression and was used to classify patients into low- and high-risk groups using an optimization algorithm for the minimum P value. POU5F1 upregulation was strongly associated with a higher risk of prostate cancer recurrence (P = 0.014, Figure 2C). Moreover, analysis of publicly available datasets from two additional cohorts of patients with prostate cancer showed that high POU5F1 levels additionally indicated poor BCR-free and overall survival (P ≤ 0.036, Figures 2D and E). These results provided a clinical rationale for using POU5F1 as a prognostic marker in advanced prostate cancer.

Figure 2.

Functional analyses of POU5F1 rs2394882. (A) Correlation of rs2394882 genotypes with POU5F1 expression: POU5F1 mRNA expression tended to be lower in rs2394882 AA carriers. (B) More advanced prostate cancers tended to show higher POU5F1 expression. Expression of POU5F1 mRNA correlates with (C) BCR-free survival in the dataset from Taylor et al. (2010), (D) BCR-free survival in the dataset from Lapointe et al. (2004), and (E) overall survival in the TCGA dataset. Increased POU5F1 expression was significantly associated with poor prostate cancer prognosis. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of patients.

Discussion

Biomarkers that allow predicting the individual clinical course of a disease are desirable. Genetic markers have certain advantages over clinicopathological indicators in that they can be utilized preoperatively, are easy to assess using blood samples, and allow objective interpretation without individual bias. We found that the genetic biomarker rs2394882 in the prostate CSC marker gene POU5F1 was associated with disease recurrence. Additionally, elevated POU5F1 gene expression correlated with aggressive cancers and poor clinical outcomes. If these findings are confirmed, POU5F1/rs2394882 should be considered as a biomarker for optimizing treatment modalities to improve the survival of patients with prostate cancer.

The SNP rs2394882 is located within intron 3 of POU5F1 and is predicted to affect mRNA splicing by altering exonic splicing enhancer binding (Table 1). POU5F1 (also known as OCT4) is a member of the POU family of transcription factors, whose main function is to bind the octameric sequence motif (ATGCAAAT), thus activating target gene expression 25. The POU5F1 gene undergoes alternative splicing to generate three mRNA isoforms: OCT4A, OCT4B, and OCT4B1 26. OCT4A, the main isoform, acts as a transcription factor to regulate stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal 27. On the other hand, as OCT4B1 levels have been observed to increase following heat stress, OCT4B and OCT4B1 are thought to be related with the stress response and anti-apoptotic properties rather than with stemness maintenance 28. Further, Roadmap Epigenomics data indicate that rs2394882 and several linked SNPs are situated at a locus with enhancer-related histone modification patterns in the human induced pluripotent stem cell line iPS DF 19.11 and in other cell types (Table S2). Additionally, rs2394882 is predicted to alter multiple transcription factor-binding sites; the present expression quantitative trait locus analysis supported that the risk allele C at rs2394882 is associated with increased POU5F1 expression (Figure 2A). POU5F1 is overexpressed in a wide variety of human cancers, including bladder, brain, lung, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, renal, seminoma, and testicular cancers 29. POU5F1 overexpression has been also observed in the tissues of patients with recurrent prostate cancer 30, 31. Moreover, POU5F1 reportedly is upregulated in both docetaxel- and mitoxantrone-resistant human prostate cancer cells 32. Taken together, these data are consistent with our present finding that patients carrying the rs2394882 risk allele C have higher POU5F1 expression, which in turn is correlated with more aggressive forms of prostate cancer and poor patient prognosis (Figure 2). Validation of the functional roles of POU5F1 during prostate cancer progression should provide novel insights into the involvement of CSCs in carcinogenesis, as well as into the potential of POU5F1 as a therapeutic target.

In conclusion, our study provided evidence that genetic variants of CSC-related genes influence patient outcome, and revealed POU5F1 as a potential therapeutic target in prostate cancer. However, our findings in the homogeneous Taiwanese cohort used in this study may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups. A selection bias may be present due to the retrospective, hospital-based nature of this study. Furthermore, the relatively small sample size and limited outcome events in some strata may have increased the role of chance in the present findings. Additional and larger studies are warranted to validate our findings and enable the development of more effective personalized treatment for patients with prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (grant nos: 103-2314-B-037-060, 104-2314-B-650-006, 104-2314-B-037-052-MY3, 105-2314-B-650-003-MY3, and 106-2314-B-039-018), the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (grant no: KMUH105-5R42), the E-Da Hospital (grant nos: EDPJ104059, EDPJ105054, and EDAHP104053), and the China Medical University (grant no: CMU105-S-42). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We thank Chao-Shih Chen for data analysis, and the National Center for Genome Medicine, Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, for technical support. The results published here are based in part on data generated by the HapMap, HaploReg, and TCGA projects.

Abbreviations

- RP

radical prostatectomy

- CSC

cancer stem cell

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- BCR

biochemical recurrence

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen.

References

- 1.Conford P, Bellmunt J, Bolla M. et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of relapsing, metastatic, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71:630–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M. et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2017;71:618–29. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamburger AW, Salmon SE. Primary bioassay of human tumor stem cells. Science. 1977;197:461–3. doi: 10.1126/science.560061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pardal R, Clarke MF, Morrison SJ. Applying the principles of stem-cell biology to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:895–902. doi: 10.1038/nrc1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C. et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10946–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurt EM, Kawasaki BT, Klarmann GJ. et al. CD44+ CD24- prostate cells are early cancer progenitor/stem cells that provide a model for patients with poor prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:756–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni J, Cozzi P, Hao J. et al. Cancer stem cells in prostate cancer chemoresistance. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2014;14:225–40. doi: 10.2174/1568009614666140328152459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang CY, Huang SP, Lin VC. et al. Genetic variants in the Hippo pathway predict biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8556. doi: 10.1038/srep08556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang SP, Huang LC, Ting WC. et al. Prognostic significance of prostate cancer susceptibility variants on prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:3068–74. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang SP, Levesque E, Guillemette C. et al. Genetic variants in microRNAs and microRNA target sites predict biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy in localized prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2661–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang SP, Ting WC, Chen LM. et al. Association analysis of Wnt pathway genes on prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:312–22. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0698-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu CC, Lin VC, Huang CY. et al. Prognostic significance of cyclin D1 polymorphisms on prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(Suppl 3):S492–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2869-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedland SJ, Sutter ME, Dorey F. et al. Defining the ideal cutpoint for determining PSA recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Prostate-specific antigen. Urology. 2003;61:365–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maitland NJ, Collins AT. Prostate cancer stem cells: a new target for therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2862–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trerotola M, Rathore S, Goel HL. et al. CD133, Trop-2 and alpha2beta1 integrin surface receptors as markers of putative human prostate cancer stem cells. Am J Transl Res. 2010;2:135–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ugolkov AV, Eisengart LJ, Luan C. et al. Expression analysis of putative stem cell markers in human benign and malignant prostate. Prostate. 2011;71:18–25. doi: 10.1002/pros.21217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan HY, Chiou JJ, Tseng WH. et al. FASTSNP: an always up-to-date and extendable service for SNP function analysis and prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W635–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International HapMap C. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–96. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao BY, Pao JB, Lin VC. et al. Individual and cumulative association of prostate cancer susceptibility variants with clinicopathologic characteristics of the disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1232–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang SP, Lan YH, Lu TL. et al. Clinical significance of runt-related transcription factor 1 polymorphism in prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2011;107:486–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H. et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lapointe J, Li C, Higgins JP. et al. Gene expression profiling identifies clinically relevant subtypes of prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:811–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304146101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguirre-Gamboa R, Gomez-Rueda H, Martinez-Ledesma E. et al. SurvExpress: an online biomarker validation tool and database for cancer gene expression data using survival analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu G, Scholer HR. Role of Oct4 in the early embryo development. Cell Regen (Lond) 2014;3:7. doi: 10.1186/2045-9769-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao S, Yuan Q, Hao H. et al. Expression of OCT4 pseudogenes in human tumours: lessons from glioma and breast carcinoma. J Pathol. 2011;223:672–82. doi: 10.1002/path.2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai SC, Chang DF, Hong CM. et al. Induced overexpression of OCT4A in human embryonic stem cells increases cloning efficiency. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C1108–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00205.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asadzadeh J, Asadi MH, Shakhssalim N. et al. A plausible anti-apoptotic role of up-regulated OCT4B1 in bladder tumors. Urol J. 2012;9:574–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoenhals M, Kassambara A, De Vos J. et al. Embryonic stem cell markers expression in cancers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383:157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guzel E, Karatas OF, Duz MB. et al. Differential expression of stem cell markers and ABCG2 in recurrent prostate cancer. Prostate. 2014;74:1498–505. doi: 10.1002/pros.22867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosaka T, Mikami S, Yoshimine S. et al. The prognostic significance of OCT4 expression in patients with prostate cancer. Hum Pathol. 2016;51:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linn DE, Yang X, Sun F. et al. A role for OCT4 in tumor initiation of drug-resistant prostate cancer cells. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:908–16. doi: 10.1177/1947601910388271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables.