Abstract

Oligodendrocyte development has been studied for several decades, and has served as a model system for both neurodevelopmental and stem/progenitor cell biology. Until recently, the vast majority of studies have been conducted in lower species, especially those focused on rodent development and remyelination. In humans, the process of myelination requires the generation of vastly more myelinating glia, occurring over a period of years rather than weeks. Furthermore, as evidenced by the presence of chronic demyelination in a variety of human neurologic diseases, it appears likely that the mechanisms that regulate development and become dysfunctional in disease may be, in key ways, divergent across species. Improvements in isolation techniques, applied to primary human neural and oligodendrocyte progenitors from both fetal and adult brain, as well as advancements in the derivation of defined progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells, have begun to reveal the extent of both species-conserved signaling pathways and potential key differences at cellular and molecular levels. In this article, we will review the commonalities and differences in myelin development between rodents and man, describing the approaches used to study human oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination, as well as heterogeneity within targetable progenitor pools, and discuss the advances made in determining which conserved pathways may be both modeled in rodents and translate into viable therapeutic strategies to promote myelin repair.

Keywords: Human cell implantation, Oligodendrocyte progenitor, Remyelination

1. Introduction

Although first described and categorized by Pio del Rio Hortega in the early 20th century (see Perez-Cerda et al., 2015 for review), understanding of the origin and function of oligodendroglia and their progenitor cells has lagged in the rapidly advancing field of neuroscience. Indeed, for a long time, their primary functions were believed to involve only the formation and maintenance of myelin to enable rapid saltatory conduction. Accumulating evidence has established that there are diverse contributions of oligodendrocytes to overall nervous system function (Nave and Werner, 2014), and it has become apparent that oligodendroglia provide key metabolic and trophic support to axons (Lee et al., 2012; Morrison et al., 2013). The loss of this support is apparent in neurologic diseases characterized by primary demyelination, such as multiple sclerosis (MS), in which demyelinated axons are more susceptible to subsequent damage/injury (Nave and Trapp, 2008). As such, neurodegeneration is a major consequence of chronic demyelination (Trapp and Nave, 2008).

Unlike neurodegeneration, loss of oligodendrocytes and myelin in the adult CNS can be restored by a regenerative process known as remyelination. Resident oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) are recruited to regions of demyelination undergoing differentiation and new myelin synthesis (reviewed in Franklin and Goldman, 2015). Remyelination not only restores saltatory conduction and function (Jeffery and Blakemore, 1997; Smith et al., 1979), but also provides protection to demyelinated axons (Irvine and Blakemore, 2008), possibly by the restoration of trophic support, as well as providing a barrier to noxious stimuli. As such, proper development, maintenance, and replenishment of lost oligodendrocytes are important areas of study with regard to the treatment of various neurologic and pathologic conditions. In addition, there may be contributions from non-myelinating types, such as precursors and perineuronal oligodendrocytes, as well as astrocytes, microglia, and immune cells, which may also provide trophic/metabolic support or similarly promote survival and protection of neurons and axons (Dimou and Gallo, 2015; Franklin and Goldman, 2015). This review will focus primarily on human OPCs, highlighting recent studies examining their use in in vivo models of myelination, and their comparison to rodent species.

2. Myelin pathology and animal models

Collectively referred to as leukodystrophies, many hereditary diseases are marked by dysmyelination, including lysosomal storage diseases and metabolic disorders, and hypomyelination, such as in Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease (reviewed in Franklin and Goldman, 2015; Pouwels et al., 2014). There are also several acquired demyelinating conditions that vary widely in etiology, for example, ischemia-related conditions (such as white matter loss in vascular dementia), with diabetes/hypertension (Franklin and Ffrench-Constant, 2008), as a result of chemo/radiotherapy (Rane and Quaghebeur, 2012), and most commonly, immune-mediated demyelination, such as in MS (Lassmann et al., 2007; Noseworthy et al., 2000). Interestingly, unlike their animal models (discussed below), acquired demyelinating diseases in humans frequently display chronic demyelination.

Various genetic animal models have been developed in an effort to better study hereditary leukodystrophies, with some success (reviewed in Duncan et al., 2011). Several genetic models for leukodystrophies seem to closely model the pathologies observed in humans, such as mice deficient in Aspa for Canavan disease (Matalon et al., 2000) and overexpressing Lmnb1 for adult-onset autosomal-dominant leukodystrophy (Heng et al., 2013). However, not all genetic models accurately reflect the human diseases for which they are developed. For example, the twitcher mouse, a model for Krabbe disease, which is caused by a mutation in the gene encoding galactosylceramidase, exhibits a disparate disease progression that is less severe early on and does not show the same peripheral nervous system effects (Suzuki and Suzuki, 1983). Moreover, mutations in ABCD1 in humans cause X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy with pronounced cerebral demyelination (Schaumburg et al., 1975), which is not reproduced in knockout mouse models (Brites et al., 2009).

Several rodent models of demyelination/remyelination have been described (Franklin and Ffrench-Constant, 2008). In an attempt to avoid confounding effects of experimental modulation on immune-mediated demyelination (such as in experimental autoimmune/allergic encephalomyelitis), toxin-based approaches to induce demyelination have predominated. However, such studies have primarily shown an acceleration of remyelination, rather than induced remyelination of an otherwise chronically demyelinated plaque (for example Deshmukh et al., 2013; Fancy et al., 2011b; Huang et al., 2011; Mei et al., 2014; Mi et al., 2009; Najm et al., 2015). Indeed, many preclinical studies have focused on models in young animals that exhibit efficient remyelination. For example, in young-adult rodents (~8–10 weeks), remyelination is largely complete 3–4 weeks after lesioning of white matter by local injections of either lysolecithin or ethidium bromide (Arnett et al., 2004; Miron et al., 2013; Woodruff and Franklin, 1999). Although remyelination is delayed in older rats, it nevertheless reaches completion by nine weeks following lesion induction (Shields et al., 1999). Likewise, knockout of Olig1 delays remyelination, but extensive repair was still apparent two months later (Arnett et al., 2004). Remyelination of small focal lesions remains a robust and efficient process following repeated rounds of focal demyelination (Penderis et al., 2003). Systemic treatment of mice with cuprizone, a toxic copper chelator, leads to oligodendrocyte death and demyelination (Blakemore, 1973; Matsushima and Morell, 2001). Young C57BL/6 mice fed 0.2% cuprizone exhibit profound demyelination in the corpus callosum after five weeks, which is followed by robust remyelination two weeks after the toxin treatment is stopped (Arnett et al., 2004; Mason et al., 2001). Moreover, signs of remyelination can be observed even during cuprizone treatment (Matsushima and Morell, 2001). Although chronic demyelination has been reported with longer cuprizone treatment (Armstrong et al., 2006; Mason et al., 2001; Mason et al., 2004), use of this model is complicated by systemic effects, including severe weight loss and death (Matsushima and Morell, 2001), as well as pronounced changes in axonal caliber (Mason et al., 2001) and variable axonal damage (Stidworthy et al., 2003).

In terms of modeling cell-based repair, animal models of hypomyelination have been particularly advantageous for evaluating strategies to aid in regenerative and therapeutic repair. One such model is the shiverer mouse, which does not express myelin basic protein, a chief component of the myelin sheath, and has disrupted myelin compaction and neurologic dysfunction. Indeed, when combined with an immunocompromised host such as rag2, this model is particularly well suited to the study and manipulation of human oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination (Abiraman et al., 2015).

Perhaps unexpectedly, this growing body of research has exemplified the fact that there are species-specific differences with respect to myelin development and regeneration. The inability to effectively model many human conditions, along with a multitude of genomic and sequencing studies examining in vitro models, have highlighted the fact that human and rodent biology, though similar in many respects, have very important and consequential differences (summarized in Table 1). With an ultimate goal of discovering a strategy for translational application to the clinic, it is imperative that we develop a clearer understanding of these differences, and of human glial biology in general.

Table 1.

Rodent and human OPC and oligodendrocyte biology compared.

| |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Similarities | Differences |

| Development | |

| Adult-derived progenitors more readily differentiate than fetal-derived ones in both species (Lin et al., 2009; Windrem et al., 2004) | Gliogenesis occurs during gestation in humans, but postnatally in rodents (Craig et al., 2003); |

| Myelination is markedly prolonged in humans, and continues over several decades (Semple et al., 2013); | |

| Humans have a much greater proportion of subcortical white matter relative to cortical volume (Schoenemann et al., 2005) | |

| Transcriptional and proliferative regulation | |

| Both species show the same progression of transcriptional regulation and surface markers through lineage stages (Buchet and Baron-Van Evercooren, 2009); significant overlap between mouse and human OPC transcriptomes (Sim et al., 2009) | Oligodendrocyte fate is induced by ASCL1 in mouse neural precursors, but only by SOX10 in human cells (Wang et al., 2014); |

| Human OPCs express 244 genes not expressed in mouse cells (Sim et al., 2009); | |

| Human progenitors proliferate at a higher rate and for a longer period of time than rodent cells (Windrem et al., 2008); | |

| Telomerase activity decreases with successive passages of human neural precursors, but is maintained in rodent-derived cells (Ostenfeld et al., 2000) | |

| Signaling | |

| Responses to most growth factors (e.g., platelet-derived growth factor, neurotrophin-3) are comparable between human and rodent precursors and progenitors (Wilson et al., 2003) | Fibroblast growth factor 2 does not promote generation of oligodendrocytes from human-derived precursors (Chandran et al., 2004), but promotes specification and proliferation of mouse-derived cells via activation of sonic hedgehog signaling (Gabay et al., 2003) |

| Disease models | |

| Rodent models resemble Canavan disease (Matalon et al., 2000) and adult onset leukodystrophy (Heng et al., 2013) | Twitcher does not accurately reflect Krabbe disease (Suzuki and Suzuki, 1983); |

| Mutations in Abcd1 (Brites et al., 2009) do not recreate the cerebral demyelination observed in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (Schaumburg et al., 1975) | |

3. Human-specific aspects of oligodendrocyte and myelin development

Evolutionary studies of brain development have typically focused on the impressive increases in brain volume/weight and total number of neurons in the cerebral cortices of adult humans (for review, see Hofman, 2014; Roth and Dicke, 2005). Human brain volume is approximately 1400 cm3 compared to a mouse brain of only 0.5 cm3, representing an increase of >2000-fold. As a consequence of this massive increase in volume, the distances traversed by transcallosal and other cortical fibers are substantially increased. In order to maintain the ability to respond rapidly with a larger brain, the diameter of axons and the proportion of myelinated axons in the subcortical white matter tracks are greatly increased in primates and humans. The increase in callosal myelination is dramatic, with only ~35% of callosal fibers myelinated in rodents, increasing to 70% in macaques (Wang et al., 2008), and likely higher in human brain. Increased myelination in subcortical tracts reduces not only transmission delay, but also the metabolic burden imposed by non-saltatory conduction. This is reflected by the increased proportion of subcortical white matter to total cortical volume, from <10% in mice to over 50% in primates and humans (Schoenemann et al., 2005; Ventura-Antunes et al., 2013). The disproportionate increase in white matter volume, particularly in prefrontal white matter in humans versus other primates, further suggests the evolutionary importance of white matter function and rapid conduction (Schoenemann et al., 2005).

Recently, it has been estimated that 4–6 × 109 oligodendrocytes are present in the adult human corpus callosum (Yeung et al., 2014). Using an MRI-estimated volume (Lebel et al., 2012), this calculates to approximately 105 oligodendrocyte cells/mm3, suggesting that the entire white matter in the human brain may contain as many as 5 × 1011 oligodendrocytes. The generation of such a large number of myelinating oligodendrocytes in the human compared to the rodent brain presents a developmental challenge. One of the most obvious differences between human and rodent myelination is in the developmental time course. For comparison, cortical neurogenesis occurs over an embryonic period that is ten times longer in monkeys than in rodents (Rakic, 1974). Likewise, myelin development is prolonged. Processes that take days or weeks to complete in the rodent occur over many months, even decades, in human development (see Semple et al., 2013 for review).

Rodent oligodendrocyte generation peaks at postnatal day 14 and myelination is largely completed by day 60. However, substantial adult oligodendrocyte generation and myelin plasticity occur in subsequent months (Rivers et al., 2008). In contrast, the majority of human oligodendrocyte generation and myelination occurs over a developmental period of 3–5 years (Nakagawa et al., 1998; Yeung et al., 2014), with linear increases in myelin volume thereafter, occurring from ages 4 to 22 (Giedd et al., 1999). Whether the adolescent increase in white matter volume is due to increased oligodendrocyte generation or myelin plasticity as described in the rodent is controversial (Yeung et al., 2014). Thus, the bulk of human oligodendrocyte generation occurs over a period ~10 times longer than in the rodent, and initial myelination takes >45 times longer.

The extended period for neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis in the human provides the necessary time for successive cell cycles needed for expansion of the neural and glial progenitor pools. Interestingly, the primate subventricular zone (SVZ) undergoes massive expansion compared with the rodent and becomes subdivided into distinct inner and outer regions delineated by cholinergic fibers emanating from the immature lateral geniculate nucleus (Smart et al., 2002). The outer SVZ is unique to primates and displays distinct progenitor diversity and pattern of proliferation compared to rodent SVZ (Betizeau et al., 2013). In addition, the G1 phase of the cell cycle typically lengthens during cortical development (Calegari et al., 2005). However, in the mouse SVZ, neurogenic and expanding divisions can be distinguished on the basis of a substantially longer S phase in self-renewing division. Although the cell-cycle time during primate neurogenesis is significantly longer than in murine development, the primate brain undergoes a period of accelerated cell-cycle kinetics toward the end of embryonic neurogenesis (Kornack and Rakic, 1998). This is associated with increased proliferative divisions that likely contribute to the rapid thickening of the outer SVZ and expansion of neurogenic and later gliogenic pools (Betizeau et al., 2013). Interestingly, transcriptional analysis of human and murine fetal neocortex compared immediately following OPC specification indicates that the outer SVZ contains more oligodendrocyte lineage-specific genes (SOX10, OLIG1), suggesting that this primate-specific structure is relatively enriched with OPCs (Fietz et al., 2012).

The specification of bona fide OPCs in rodents likely coincides with the expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα/CD140a) at embryonic day 13/14 (Pringle and Richardson, 1993). In humans, these CD140a/PDGFRα-defined progenitors are first detectable in the first trimester (Jakovcevski and Zecevic, 2005), and gradually increase in relative frequency late in the second trimester (23 weeks gestational age), at that point comprising up to 5% of all cortical and intermediate zone cells (Sim et al., 2011). Human CD140a+ OPCs are themselves heterogeneous, containing both bipotential O4− and O4+ oligodendrocyte-biased progenitor cells (Abiraman et al., 2015). Back and colleagues elegantly compared the appearance of pre-oligodendrocytes— defined by O4+O1−antigen expression, which likely overlaps with oligodendrocyte-biased OPCs (Back et al., 2001)—to similarly defined cells in developing rodent brain (Craig et al., 2003). O4+O1− cells were highly abundant in early postnatal mouse brain, and late during the second trimester in humans. As such, Back and colleagues concluded that oligodendrocyte progression in postnatal day 2–7 rodents is similar to that in 18–27-week fetal cerebral white matter (Craig et al., 2003).

Intrinsic OPC differences between species became readily apparent when fetal human OPCs were implanted into neonatal hypomyelinated mice. Human CD140a-defined OPCs isolated during the late second trimester require more than eight weeks to begin myelinating the shiverer mouse brain, with differentiation occurring after a prolonged period of proliferation and migration (Sim et al., 2011). Similar experimental studies also demonstrated that the proliferation of human cells is prolonged, and at a higher rate, compared to transplanted rodent-derived cells (Windrem et al., 2008; Windrem et al., 2014). This results in an almost complete replacement of native rodent OPCs with human-derived versions over time. Together with the observed delay in myelination, human OPCs appear to follow the human timeline for expansion and differentiation, despite being in the rodent environment. Given the relative rapidity of human oligodendrocyte differentiation in vitro (see below), this implies that the response of human OPCs to the same murine environmental and niche-derived signals is vastly different. Practically, the slow rate of myelination by transplanted human OPCs renders many rodent models of remyelination and repair unconducive for the study of transplanted human cells, as endogenous murine precursors would likely completely repair a demyelinated lesion in 3–4 weeks (see above for discussion) prior to the initiation of human OPC differentiation at 8–12 weeks. The use of fully humanized glial chimeras, in which human cells replace resident populations of rodent progenitors (Windrem et al., 2014), may provide a more appropriate means to directly study human remyelination.

4. Isolation and study of human oligodendrocyte progenitors

Various methods have been described for the isolation of glial cells and OPCs from rodent tissues, and were recently reviewed elsewhere (Chew et al., 2014). However, the majority of these techniques do not readily translate to human tissues, likely due to differences in enzymatic dissociation methods and species- and tissue-dependent antibody specificities. As such, and due to the relative scarcity of human tissue, the study of human primary OPCs has lagged behind that of the rodent.

Initial approaches to culture human OPCs did not employ specific antigenic isolation (Armstrong et al., 1992). While important in establishing the presence of mitotic OPCs in human brain (Gogate et al., 1994; Scolding et al., 1995), these techniques were limited and did not facilitate the study of this cell type. In 1999, Steve Goldman's group described a method to identify and purify dividing progenitors from human subcortical white matter (Roy et al., 1999). Dissociated cells obtained from adult human subcortical white matter were transfected with a reporter plasmid to express GFP under direction of an early CNP promoter and subsequently isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Although selective, improved yields were required and subsequent methods utilized immunoselection for the ganglioside A2B5 marker (Nunes et al., 2003; Windrem et al., 2002). This approach was extended to fetal human brain (Ruffini et al., 2004). However, to avoid contamination with neurogenic progenitors, A2B5+ cells were depleted for PSA-NCAM antigenicity to generate a highly myelinogenic population (Windrem et al., 2004; Windrem et al., 2008). Fetal A2B5+PSA-NCAM− cells were themselves highly heterogeneous. Interestingly, we found that the fraction of A2B5+PSA-NCAM− cells capable of oligodendrocytic differentiation in vitro could be better defined by expression of CD140a/PDGFRα (Sim et al., 2011). Indeed, when human fetal CD140a+ cells were isolated, almost one-third were capable of rapid differentiation into O4+ cells after just four days in vitro, and rapidly upregulated myelin basic protein (mRNA and protein) over the same time course. In stark contrast, similarly isolated and cultured A2B5+CD140a− cells were not enriched in OLIG2 or capable of appreciable O4+ oligodendrocyte differentiation (Sim et al., 2011). Thus, while A2B5 remains a useful marker for isolation of OPCs from adult human white matter, the use of CD140a/PDGFRα for fetal tissue isolation has become more common in recent years (Moore et al., 2015; Ortega et al., 2013).

5. Human oligodendrocyte development in vitro

Oligodendrocytes can differentiate from glial and neural precursors, as well as from parent stem cell populations, and species-specific differences in their differentiation in vitro have been studied. Human neural precursor cells (NPCs) display broadly the same sequence of transcription factors and marker expression during OPC specification and maturation as rodent cells in vitro (reviewed in Buchet and Baron-Van Evercooren, 2009). However, unlike their rodent counterparts, human NPCs generate far fewer oligodendrocytes (Ostenfeld et al., 2002). When fetal NPCs are purified on the basis of either CD133 cell-surface antigenicity (Uchida et al., 2000) or activity of NPC-expressed enhancers (Keyoung et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2010), these cells retain the capacity for oligodendrocyte differentiation in vitro, albeit at very low levels. However, it appears that the oligodendrocytes generated from CD133-defined cells were more likely a result of contaminating CD133+CD140a+ OPCs, rather than from differentiating stem cells (Wang et al., 2013a). Thus, the environmental or niche factors that instruct OPC fate are poorly understood, and unlike the rodent, the progression to OPC fate is neither rapid nor efficient.

The responses of human and rodent OPCs to many growth factors in vitro, such as PDGF-AA, neurotrophin-3, and glial growth factor, appear to be grossly similar (Cui et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2003). Indeed, a number of the reported human-specific differences in factor responsiveness were likely due to isolation and culture techniques that did not enrich for mitotic PDGFRα-expressing human OPCs. However, unlike with comparable NPCs isolated from embryonic rodent spinal cord, fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) treatment substantially reduced the generation of oligodendrocyte lineage cells in neural precursors isolated from fetal human spinal cord (Chandran et al., 2004), which was also observed in CD140a+ human OPCs isolated from second-trimester forebrain (Sim, unpublished data). Indeed, whereas FGF-2 induces OPC specification and proliferation via endogenous sonic hedgehog (SHH) activation in mouse neural precursors (Gabay et al., 2003), in human cells, it results in simultaneous downregulation of SHH expression and increases in SHH pathway repressors (Hu et al., 2009a). Interestingly, species differences in trophic requirements have been reported between mouse and rat, where only mouse-derived cells require cAMP signaling for survival in vitro (Horiuchi et al., 2010). Another potentially important difference observed between human and rodent NPCs in vitro involves differences in telomerase activity and telomere length. The level of telomerase activity in fetal human-derived neural precursors, indicative of their proliferative and self-renewal capability, decreases with successive passages, however, the high level of telomerase activity and longer telomere length was maintained in NPCs derived from rats (Ostenfeld et al., 2000). The role of telomerase and mechanisms by which telomere length are maintained are indeed species-specific (Blackburn et al., 2015), but the relevance to oligodendrocyte specification and differentiation remains to be determined.

6. Human OPCs from embryonic stem (ES) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

Unlike primary progenitor cells isolated directly from brain tissue, pluripotent stem cells can be expanded and passaged essentially indefinitely, while still retaining multipotency. Human ES cells have been directed to NPC and OPC fates, and several groups have demonstrated the capacity to generate small numbers of oligodendrocytes following implantation into the rodent brain and spinal cord (Hu et al., 2009b; Izrael et al., 2007; Nistor et al., 2005). Additionally, OPCs derived from human ES cells can provide functional recovery after ablation with radiotherapy (Piao et al., 2015) and after spinal cord injury (Keirstead et al., 2005). These strategies typically employ the induction of neural fate via embryoid body formation, followed by ventral patterning (via SHH) and subsequent expansion in PDGF-AA-containing media. A recent alternative strategy involves induction of radial glia-like neural precursors using gradually decreasing concentrations of retinoic acid and immunoselecting for CD133+ cells (Gorris et al., 2015). These cells had a somewhat improved capacity for oligodendrocyte differentiation.

In addition to the developmental differences between species described above, important differences exist between mouse and human ES cells. Human ES cells more closely resemble epiblast-derived stem cells than inner cell mass-derived mouse ES cells (Brons et al., 2007; Tesar et al., 2007). Although both human ES cells and mouse epiblast-derived stem cells rely on activin/nodal signaling to maintain pluripotency, mouse ES cells rely on leukemia inhibitory factor and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling (De Miguel et al., 2009). Retinoic acid induces BMP expression in human ES cells, and therefore, cotreatment with the BMP antagonist, noggin, can promote OPC fate and oligodendrocyte lineage maturation (Izrael et al., 2007).

An important advancement in stem cell therapy involves the development and use of human iPSCs, which will likely obviate the need for immunosuppression in recipients (Zhao et al., 2011). In a landmark study, human iPSCs induced to an OPC fate were capable of myelinating the entire shiverer brain and rescuing the otherwise lethal hypomyelinating phenotype (Wang et al., 2013b). We have recently followed this study by showing that myelinogenic OPCs can be derived from MS patients' skin cells, demonstrating the feasibility of implanting patient-specific cells for the purposes of remyelination (Douvaras et al., 2014). However, there is an important caveat to consider regarding the use of pluripotent cells for therapeutic application, as the method for obtaining these cells is technically complex, requiring extensive and prolonged in vitro preparation prior to implantation. Furthermore, though not observed in the current studies, the potential for tumorigenesis from genetically altered pluripotent stem cells should not be ignored. One recent approach to increase the efficiency of OPC generation has been to induce OPC fate either directly from fibroblasts, or indirectly using NPCs induced from pluripotent stem cells via viral overexpression of OPC fate-instructive transcription factors. Although successful in rodent cells (Najm et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013), this has not yet been achieved in human cells using the same or similar sets of transcription factors. This is likely due to differences in the transcriptional targets regulated by OPC-specific transcription factors and by genome-wide differences in epigenetic accessibility for these factors. Indeed, we recently identified an important species-specific difference with respect to transcription factor-induced oligodendrocyte lineage determination. Although ASCL1 is known to induce oligodendrocyte fate determination in mouse NPCs (Sugimori et al., 2008), it did not induce OPC fate from human NPCs (Wang et al., 2014). Instead, we found that SOX10 overexpression was sufficient to induce myelinogenic fate from NPCs (Wang et al., 2014).

Ultimately, the generation of large numbers of human OPCs from pluripotent cells will allow not only broader clinical translation, but also the biochemical and epigenetic analyses of human OPCs that require substantial amounts of starting material. However, as the extent to which pluripotent-derived OPCs actually resemble primary OPCs is not yet defined, some caution is necessary. This is especially important given the potential for developmentally distinct populations of OPCs present in the fetal human brain. As such, the comparison between induced OPCs and primary tissue-derived cells will be an important control for future human cell-based experiments.

7. Transcriptional characterization and comparisons of human OPCs

The use of genome-wide gene expression profiling has allowed a more global approach to cross-species analysis of human and rodent OPCs. Detailed comparative analyses of transcription profiles have not yet been performed, but a comparison of human adult OPCs and mouse OPCs isolated from juvenile brain has defined some of the overlying similarities between human and rodent glial biology, as well as highlighted some of their differences (Sim et al., 2009). Notably, we found significant overlap between human and mouse transcriptomes, though this equated to only a 62% overlap, with 557 homologs of the 894 mouse glial progenitor-related genes expressed in human cells. Moreover, human cells expressed 244 genes that were not found in mouse cells. While the overall gene–gene expression relationships derived from human and mouse forebrain tissues are largely conserved between species, differences are present and remain to be fully characterized (Miller et al., 2010). Although there are no transcriptional profiles of adult human oligodendrocytes, proteomic analyses of human and mouse myelin revealed that 308 proteins are shared in myelin extracts (Ishii et al., 2009). Unfortunately, due to technical issues with regard to the methodology used, it was not possible to reliably detect differences between species.

The unbiased analysis of CD140a+ OPC gene expression signatures predicted the importance of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in human OPC commitment, as has been previously described in rodents (Conway et al., 2012). However, not all HDAC targets were similarly species conserved, with HES5 expression unaffected following HDAC inhibitor treatment. Nevertheless, transcriptional activity of a species-conserved SOX10 enhancer was similarly active in human (Pol et al., 2013) and mouse (Werner et al., 2007) OPCs. Interestingly, there is emerging evidence that the same transcription factor can have differential effects on overall gene expression in different species. ASCL1 overexpression induced a gene expression signature in NPCs that was significantly similar to mouse OPCs, but distinct from human OPCs (Wang et al., 2014). This difference accurately predicted that ASCL1 was unable to induce human OPC fate, whereas SOX10, which induces both mouse and human OPC gene signatures, was highly effective in inducing OPC fate. Such transcriptional analyses of fetal human OPCs have also permitted the characterization of a more diverse population encompassing NPCs, OPCs, and subfractions that may define distinct lineage-related populations (see also the following section on human OPC heterogeneity).

Adult human A2B5-defined OPCs were found to express a unique profile of genes encoding cell-surface receptors, including PTPRZ1, and demonstrate autocrine BMP signaling that regulates their homeostasis in the adult parenchyma (Sim et al., 2006). These transcriptional profiles were further refined by comparison with other glial cells using matched techniques (Sim et al., 2009). In addition, these profiles accurately predicted the sensitivity of adult human OPCs to statin drugs, and that statin treatment might bias OPCs to differentiate in human (Sim et al., 2008) and rodent (Paintlia et al., 2005) brain. Other studies have shown that the statin drug simvastatin regulates process dynamics and survival of OPCs isolated from fetal human brain (Miron et al., 2007), and can modulate remyelination following cuprizone-induced demyelination (Miron et al., 2009).

8. Human OPC heterogeneity

In the developing rodent, OPCs arise from distinct germinal sites including the ganglionic eminences and the dorsal SVZ (Richardson et al., 2006). OPCs persist in the adult white matter and cortex and continue to divide throughout life (Dimou et al., 2008; Rivers et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2011), but appear largely restricted to oligodendrocyte fate in response to injury or demyelination (Dimou et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2010; Zawadzka et al., 2010). Although it appears that these cells are poised to respond following injury, their role in plasticity-related changes and other possible functions are as yet poorly defined (reviewed in Dimou and Gallo, 2015; Richardson et al., 2011). There is some evidence of OPC heterogeneity, as OPCs behave differently in the adult cortex and corpus callosum. The cell cycle differs between grey and white matter, ranging from 3 to 10 days in the corpus callosum and from 18 to 37 days in the cortex (Psachoulia et al., 2009; Simon et al., 2011; Wang and Young, 2014). Transplantation of grey and white matter-derived OPCs also reveals functional differences in their ability to form myelinating oligodendrocytes, with white matter-derived cells differentiating more rapidly after engraftment into adult cortex (Vigano et al., 2013). Recently, G protein-coupled receptor 17 expression was found to delineate two pools of OPCs, where those that did express did not give rise to oligodendrocytes until after injury to the CNS (Vigano et al., 2016).

Human OPC heterogeneity has, until recently, not been directly examined. In addition, the extent to which OPC germinal sites are conserved in the human, and their relative contribution to the massive number of oligodendrocytes needed to myelinate the adult human brain, have not yet been addressed. We and others have used the combination of specific cell surface antigen-based isolation techniques and gene expression analysis to establish the transcriptional profile of human neural and glial progenitor cells (reviewed in Sim and Goldman, 2012). Multicolor fluorescence-activated cell sorting-based approaches have characterized several populations with overlapping antigen expression, and subsequent transcriptomic analyses identified additional candidate antigens that can be used to serially dissect human OPC heterogeneity. For example, the analysis of A2B5-sorted cells from 23-week gestation fetal forebrain revealed that these progenitors were highly heterogeneous and not substantially enriched for PDGFRA or CSPG4 mRNAs (Sim et al., 2011). Direct CD140a/PDGFRα-based isolation gives highly purified progenitors that express OPC-specific genes at levels greater than tenfold compared to the tissue dissociate. Interestingly, this analysis identified CD9 as an additional surface antigen expressed by OPCs, which was expressed on approximately 50% of CD140a+ OPCs. Expression of CD9 was not associated with differences in subsequent oligodendrocyte differentiation, but it was noted that CD9+CD140a− cells showed cytoplasmic OLIG2 expression, suggesting that these cells may be in a transitional state toward the astrocytic lineage. Combination of CD140a and the NPC marker CD133 also identified a subpopulation of OPCs expressing both antigens (Wang et al., 2013a). However, these progenitors had an mRNA profile that was similar to CD140a+CD133− OPCs, with fewer than 50 genes that were differentially regulated, and generated oligodendrocytes with similar efficiency.

Recently, we described the separation of three phenotypically distinct stages of OPC and oligodendrocyte lineage using the combination of CD140a and O4 antigens (Abiraman et al., 2015). Intriguingly, CD140a+O4+ cells, which comprised ~30% of all CD140a+ cells, were mitotic PDGF-AA-responsive progenitors that expressed a gene expression profile consistent with OPC fate, rather than immature oligodendrocytes. Nevertheless, these cells were biased toward oligodendrocyte differentiation and were significantly less responsive to serum-derived signals, such as BMPs, that drive astrocytic fate. Thus, there are functionally distinct subpopulations of both bipotential and oligodendrocyte-biased OPCs in human fetal brain. Interestingly, even highly purified CD140a+O4+ cells are still phenotypically heterogeneous, as not all cells undergo oligodendrocytic differentiation at the same rate in vitro. Single cell RNA-seq of these purified subpopulations will no doubt resolve whether OPC subpopulations can be further divided, or if differences within these are largely due to the stochastic differences and the bursting nature of gene transcription at the single cell level, as has been described for similar analyses (Stegle et al., 2015).

Less is known about subpopulations and regional differences in adult human OPCs. One recent study separated A2B5-defined OPCs isolated from adult tissue into O4high and O4− subfractions (Leong et al., 2014), but differences in phenotypic or myelinogenic properties have not been investigated in detail. It is not clear whether O4-expressing cells in dissociates of adult white matter indicate the presence of mitotic progenitors or represent post-mitotic immature oligodendrocytes. With respect to regional differences, we have characterized the transcriptional profile of adult human A2B5-defined OPCs (Sim et al., 2006; Sim et al., 2009). When OPCs were isolated from matched grey and white matter obtained from non-tumorigenic resections, there were very few differentially regulated genes, suggesting that these populations are equivalent in the adult human brain (Sim, unpublished observations).

9. Understanding human myelin development using cell transplantation

Therapeutic myelin repair has been a long-term goal of human cell implantation for several decades (Czepiel et al., 2015; Goldman et al., 2012). The purpose of such methods is to provide or replenish demyelinated lesions with a sufficient pool of capable progenitor cells to promote remyelination. Human OPC transplantation from either fetal tissue or pluripotent stem cell sources has been shown to result in functional recovery of neurologic deficits (Abiraman et al., 2015) and improved survival in hypomyelinating mice (Wang et al., 2013b; Windrem et al., 2008). Improved recovery following implantation of human OPCs has also been observed in animal models of toxin-induced demyelination (Walczak et al., 2011), spinal cord injury (Keirstead et al., 2005), and following radiation-induced injury (Piao et al., 2015).

In addition to the use of transplantation models for the assessment of potential stem cell therapies, transplantation of human cells into shiverer mice provides a reliable in vivo model of human myelination that can be used to study the molecular regulation of human OPC behavior and determine whether systemically administered drugs can enhance myelination by human OPCs. This is especially important given the general lack of success with in vitro models utilizing human myelinating glia. Few human fetal tissue-derived OPCs ensheath axons within four weeks in vitro (Cui et al., 2012; O'Guin et al., 2014). Likewise, using a method optimized for the assessment of myelination by rodent OPCs (Watkins et al., 2008), we found that, while primary CD140a+ OPCs differentiate into O1+MBP+ oligodendrocytes in vitro, very few begin ensheathing human cortical axons within 3–4 weeks (Conway et al., 2012). Indeed, we were unable to find convincing examples of compact myelin formation in vitro. One problem with these in vitro systems is that maintenance of neuronal cultures beyond four weeks becomes problematic due to loss of adherence and viability of neurons at longer time points. An attractive possibility is the use of inert plastic nanofibers, which have been shown to become ensheathed by oligodendrocyte processes and allow the formation of multi-layered compact myelin-like structures (Bechler et al., 2015). Whether human OPCs can similarly ensheath and form myelin-like structures has not yet been addressed. Thus, in vivo models are vital for the assessment of functional myelin formation, as well as for confirmation of results obtained in the culture dish.

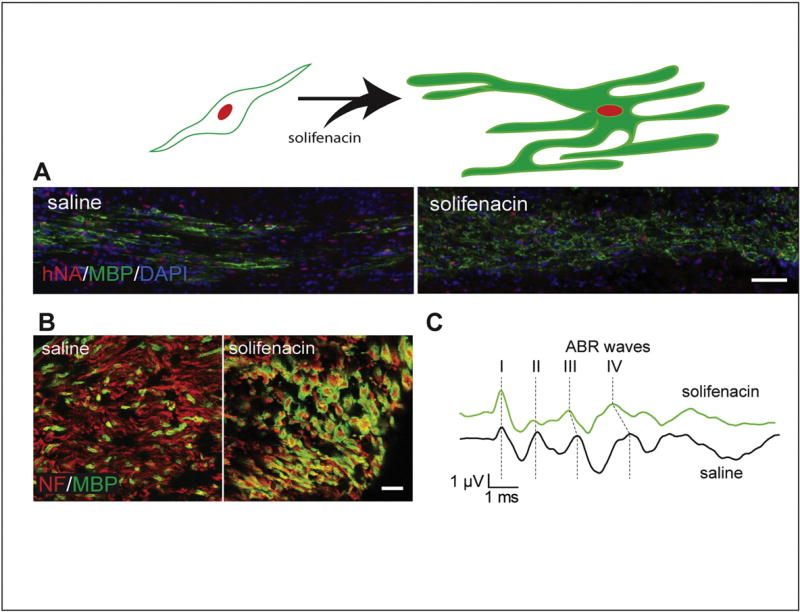

Human primary OPCs engraft successfully into shiverer white matter and progressively migrate throughout the forebrain over the course of several weeks post-implantation. The relatively long survival time of shiverer/rag2 mice (up to 20 weeks in our colony) provides sufficient time to assess effects of genetic and pharmacologic modifications on cell survival, proliferation, migration, and differentiation. As a first example of pharmacologic modulation of human OPC differentiation, our recent work documented the effects of a selective muscarinic antagonist, solifenacin, on engrafted human OPCs (Abiraman et al., 2015). Using the gene expression profile of CD140a/O4-sorted human OPCs, we determined that the muscarinic receptor type 3 would be highly expressed during commitment to oligodendrocyte-biased OPCs. Systemic treatment of a brain-permeable muscarinic receptor-selective drug was found to increase the proportion of human OPCs undergoing oligodendrocyte differentiation. More importantly, the pharmacologically induced oligodendrocyte differentiation of human OPCs transplanted into the auditory circuit accelerated conduction velocity (Fig. 1). This proof-of-principle study illustrates the potential utility of using OPC engraftment into shiverer mice to model drug responsiveness of human cells and the modulation of differentiation, migration, and proliferation. For example, although differentiation was substantially enhanced by solifenacin treatment, the induced differentiation was countered by lower engraftment (cell density and distribution), likely a result of the removal of progenitors from the cell cycle, thus reducing the size of the mitotic progenitor pool. As these studies were completed, other groups had similarly found that muscarinic receptor targeting could improve oligodendrocyte differentiation in rodent systems (Deshmukh et al., 2013; Mei et al., 2014). Thus, testing of compounds on human OPC differentiation and myelination in the shiverer/rag2 model will likely complement other animal models of demyelination/remyelination that are more commonly used (e.g., experimental autoimmune/allergic encephalomyelitis, cuprizone, and lysolecithin).

Fig. 1.

Solifenacin treatment enhances myelination and functional recovery by transplanted human oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (hOPCs). CD140a-sorted fetal-derived hOPCs were transplanted into neonatal hypomyelinated shiverer mice, which do not express myelin basic protein (MBP). A) The differentiation of transplanted hOPCs was accelerated by systemic administration of solifenacin, a muscarinic receptor antagonist, as observed as increased immunostaining for MBP in the corpus callosum after eight weeks (human nuclei are stained with hNA in red; scale bar = 100 µm). B) Solifenacin also enhanced myelination of cerebral peduncle axons (marked by neurofilament [NF]) by hOPCs when transplanted into the ventral midbrain (scale bar = 10 µm). C) The increased myelination of ventral midbrain structures resulting in increased conduction velocity and functional recovery of the auditory brainstem response (ABR), observed as reduced interpeak latencies, with significantly shorter latencies between peaks II and IV (modified from Abiraman et al., 2015).

10. Clues from transplant models: is there a critical density needed for effective OPC differentiation and myelination?

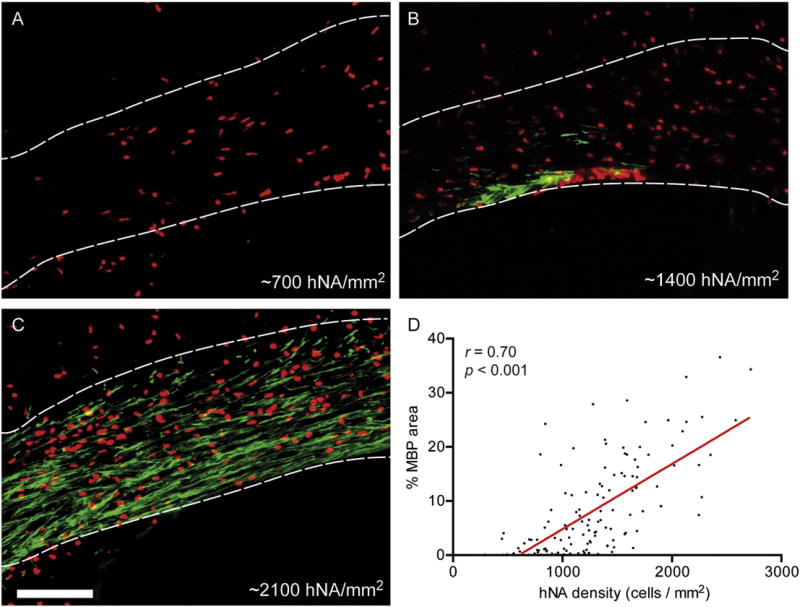

Cell transplantation provides a unique view into human OPC developmental biology. OPCs originate in various discrete germinal zones and undergo widespread migration and proliferation, leading to a colonization of brain parenchyma with a relatively even distribution throughout the adult brain. Likewise, when fetal human OPCs are transplanted into shiverer mouse forebrain, OPCs undergo progressive migration and expansion, initially in white matter tracks, and thence into cortical and subcortical grey matter (Windrem et al., 2008). The progressive engraftment is likely due to a competitive advantage over murine OPCs, the molecular basis of which is unknown (Windrem et al., 2014). MBP+ oligodendrocyte differentiation occurs as early as eight weeks post-transplantation of CD140a-defined OPCs (Sim et al., 2011). Interestingly, we have observed that oligodendrocyte differentiation occurs preferentially in engrafted regions of corpus callosum, requiring a local density of >30,000 cells/mm3 (500 cells/mm2, 16 µm sections), with increased myelination occurring at higher cell densities (Fig. 2). Density-dependent differentiation has been observed in tissue culture (Rosenberg et al., 2008), and our observations suggest that this may occur in vivo as well. If OPCs can sense their local density, as was suggested by in vivo imaging of individual neural/glial antigen 2 (NG2)+ cells (Hughes et al., 2013), then it is possible that, for successful remyelination to occur in human demyelinating diseases, endogenous progenitor cells need to first attain a sufficient cell density.

Fig. 2.

Myelination is enhanced in regions with high densities of transplanted human oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Human oligodendrocyte progenitor cells were transplanted into the corpus callosum of 2–3 postnatal day shiverer/rag2 mice (as described in Abiraman et al. (2015). A–C) The densities of engrafted human cells (human nuclear antigen [hNA], red) observed within the corpus callosum (demarcated by dotted lines) varied at 12 weeks post-transplantation. Oligodendrocyte differentiation identified by staining for myelin basic protein (MBP, green) was strongest in areas with a high density of hNA+ cells (scale bar = 100 µm). D) A strong, positive correlation was found between the density of human cells and the area of MBP staining within the corpus callosum.

Several pathologic studies have established that human OPCs persist within chronically demyelinated MS lesions (Chang et al., 2000; Scolding et al., 1998; Wolswijk, 1998). The estimates of density vary depending on the study and marker used. In normal adult white matter, OLIG2strong-defined OPCs were found at a density of ~10,000 cells/mm3 (Kuhlmann et al., 2008), similar to that determined by Frisen's group using stereotaxic counting of SOX10+NOGO-A− cells (Yeung et al., 2014). This density was increased approximately threefold in periplaque regions, but was reduced by >40% relative to normal white matter in regions of chronic demyelination (Kuhlmann et al., 2008). Interestingly, this density is much lower than the density at which engrafted human OPCs begin to myelinate host shiverer axons. This suggests that while OPCs are undoubtedly present in MS lesions, there may be an insufficient number or local density to facilitate differentiation. In contrast, following mouse spinal cord demyelination, the densities of OPCs are rarely described as <50,000 cells/mm3 (> 800 cells/mm2, 12 µm sections) (Fancy et al., 2009; Fancy et al., 2011b). In rat caudal cerebellar peduncle lesions, the density of OPCs following demyelination is >20,000 cells/mm3 in young animals and >10,000 cells/mm3 in aged adult animals (Sim et al., 2002). So, perhaps recruitment is never limiting in rodent lesions, as a huge excess of OPCs are reliably produced following a demyelinating injury, whereas in MS lesions, the density of OPCs is close to the threshold at which differentiation occurs and insufficient proliferation and prolonged quiescence become limiting factors. Consistent with this, transplanted human OPCs are mitogenic in rodent brain, expressing the Ki67 marker of active cell division (Sim et al., 2011; Windrem et al., 2008). In contrast, OPCs in MS lesions have been referred to as quiescent cells that do not co-label with Ki67 (Wolswijk, 1998). However, these mechanisms may differ in cortical demyelinating lesions. Periplaque and lesion tissues exhibited slightly increased NG2+ cell density relatively to control grey matter, albeit with substantially lower overall density estimates (2000–3000 cells/mm3) compared to the previous two studies (Chang et al., 2012).

It is important to consider that in vivo findings on myelination in rodents with human cell implantation may not directly extrapolate to outcomes in human patients. For example, the time course for observable effects will likely be prolonged, as cells implanted into human subjects will have further to migrate and may take longer to differentiate and myelinate. There are many variables challenging clinical applications (Dunnett and Rosser, 2014), including the fact that the number of cells needed for “successful” implantation is not currently known. Moreover, recent studies suggest that simply increasing the number of implanted human neural stem cells does not directly translate into greater numbers of surviving or incorporating cells in the long term (Darsalia et al., 2011; Piltti et al., 2015). In rat spinal cord, engrafted rodent OPCs do not outcompete the host OPC population, which prohibits widespread engraftment and donor-derived remyelination (Franklin et al., 1996). This suggests that there is a finite amount of trophic factors present to support survival, proliferation, and differentiation of implanted cells. Human OPCs can outcompete rodent OPCs in shiverer mouse brain, but it is not clear whether their success will be maintained when they are transplanted into a human host.

11. Additional factors influencing oligodendrocyte development

The impact of age on regenerative capacity has been well documented. Changes in remyelination with age are due in part to delayed OPC recruitment and a pronounced delay in oligodendrocyte differentiation (Sim et al., 2002). The mechanisms underlying these differences are not necessarily intrinsic to OPCs, as parabiosis studies have shown that the age-related decline can be reversed by coupling the circulation of an aged adult animal with a young adult, and that this is, in part, attributable to changes in macrophage function (Ruckh et al., 2012). Neurons and demyelinated axons themselves likely play an important role. Loss of neuronal activity, such as with deprivation of sensory input, can lower the survival of newly divided progenitor cells (Hill et al., 2014), and remyelination is likely to favor active neurons (Gautier et al., 2015; Wake et al., 2015). Moreover, there is accumulating evidence documenting the influence of stress, learning, and activity in white matter physiology (Purger et al., in press; Tomlinson et al., in press; Wang and Young, 2014). Furthermore, the processes and factors contributing to remyelination may also be the same as those that influence white matter plasticity in the adult brain (Boulanger and Messier, 2014). As such, therapeutic interventions should not rely solely on implantation of new cells, but rather be included as an adjunct to various forms of therapy to facilitate recovery of function following demyelination.

12. Conclusions and future directions

There is much that remains to be learned regarding the factors that regulate the normal development and maintenance of glial cells in the nervous system. While there are many similarities across vertebrate species, the increase in scale of both the amount of myelin produced and the number of oligodendrocytes needed dictate that some of these processes must be altered in order to achieve myelination of the human brain. As the developmental process of myelination and remyelination appear to share many molecular processes (Fancy et al., 2011a), our improved understanding of human glial development is expected to provide insight into the processes involved in remyelination. In vitro studies aimed at determining the specific roles of various factors and signaling cascades on cell fate determination, migration, and proliferation, as well as myelinating potential, are only the tip of the iceberg. Indeed, investigation of the behavior of human OPCs in vivo is indispensable in the pursuit of therapeutic strategies, though there are also many external factors influencing the ultimate fate of these cells.

Experimental studies utilizing human cells are particularly well-suited for assessing the effects of potential primary and/or adjunct pharmacologic treatments with regard to specific diseases. For example, the immune-modulating agents fingolimod and simvastatin, potential therapies for MS, have been examined for their effects on oligodendrocytes in vitro (Antel and Miron, 2008). Although the effects of some immunosuppressant agents have been examined in several research studies, this has not been explored in detail. How transplanted human cells react in the presence of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs is crucial to accurately evaluate their potential clinical benefit. This is particularly relevant based on the fact that immune cells have been shown to play an important role in remyelination (Bieber et al., 2003; Doring et al., 2015; Miron et al., 2013; Ruckh et al., 2012). Finally, cell-based therapies aimed at the restoration of myelin should be tailored to the specific causative deficit. For example, if it is a failure to differentiate that is the cause for failed remyelination attempts in MS, then cell therapy should be combined with adjunct therapies aimed at enhancing or promoting engrafted cell differentiation. On the other hand, if failure results from an insufficient density of progenitor cells, then replenishment of these cells or enhancement of proliferation would be more ideal. In all, advancements in the study of human OPC development have identified species-conserved mechanisms, but also have indicated that there are human-specific aspects that should be acknowledged and considered when extrapolating results from model-based studies to human clinical applications.

Abbreviations

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- CD140a

a CD antigen recognizing the alpha chain of platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα)

- ES

embryonic stem

- FGF-2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- iPSC

induced pluripotent stem cell

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NG2

neural/glial antigen 2

- NPC

neural precursor cell

- OPC

oligodendrocyte progenitor cell

- SHH

sonic hedgehog

- SVZ

subventricular zone

Footnotes

Support: This work was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG 5505-A-2), the Kalec Multiple Sclerosis Foundation, the Change MS Foundation, and the Empire State Stem Cell Fund through a New York State Department of Health Contract (C028108).

References

- Abiraman K, Pol SU, O'Bara MA, Chen GD, Khaku ZM, Wang J, Thorn D, Vedia BH, Ekwegbalu EC, Li JX, Salvi RJ, Sim FJ. Anti-muscarinic adjunct therapy accelerates functional human oligodendrocyte repair. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:3676–3688. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3510-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antel JP, Miron VE. Central nervous system effects of current and emerging multiple sclerosis-directed immuno-therapies. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2008;110:951–957. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong RC, Dorn HH, Kufta CV, Friedman E, Dubois-Dalcq ME. Pre-oligodendrocytes from adult human CNS. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1538–1547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01538.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong RC, Le TQ, Flint NC, Vana AC, Zhou YX. Endogenous cell repair of chronic demyelination. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2006;65:245–256. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000205142.08716.7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett HA, Fancy SP, Alberta JA, Zhao C, Plant SR, Kaing S, Raine CS, Rowitch DH, Franklin RJ, Stiles CD. bHLH transcription factor Olig1 is required to repair demyelinated lesions in the CNS. Science. 2004;306:2111–2115. doi: 10.1126/science.1103709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SA, Luo NL, Borenstein NS, Levine JM, Volpe JJ, Kinney HC. Late oligodendrocyte progenitors coincide with the developmental window of vulnerability for human perinatal white matter injury. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:1302–1312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01302.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechler ME, Byrne L, Ffrench-Constant C. CNS myelin sheath lengths are an intrinsic property of oligodendrocytes. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:2411–2416. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betizeau M, Cortay V, Patti D, Pfister S, Gautier E, Bellemin-Menard A, Afanassieff M, Huissoud C, Douglas RJ, Kennedy H, Dehay C. Precursor diversity and complexity of lineage relationships in the outer subventricular zone of the primate. Neuron. 2013;80:442–457. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieber AJ, Kerr S, Rodriguez M. Efficient central nervous system remyelination requires T cells. Ann. Neurol. 2003;53:680–684. doi: 10.1002/ana.10578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH, Epel ES, Lin J. Human telomere biology: a contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science. 2015;350:1193–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore WF. Remyelination of the superior cerebellar peduncle in the mouse following demyelination induced by feeding cuprizone. J. Neurol. Sci. 1973;20:73–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(73)90119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger JJ, Messier C. From precursors to myelinating oligodendrocytes: contribution of intrinsic and extrinsic factors to white matter plasticity in the adult brain. Neuroscience. 2014;269:343–366. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brites P, Mooyer PA, El Mrabet L, Waterham HR, Wanders RJ. Plasmalogens participate in very-long-chain fatty acid-induced pathology. Brain J. Neurol. 2009;132:482–492. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brons IG, Smithers LE, Trotter MW, Rugg-Gunn P, Sun B, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, Howlett SK, Clarkson A, Ahrlund-Richter L, Pedersen RA, Vallier L. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature. 2007;448:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature05950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchet D, Baron-Van Evercooren A. In search of human oligodendroglia for myelin repair. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;456:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calegari F, Haubensak W, Haffner C, Huttner WB. Selective lengthening of the cell cycle in the neurogenic subpopulation of neural progenitor cells during mouse brain development. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6533–6538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0778-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran S, Compston A, Jauniaux E, Gilson J, Blakemore W, Svendsen C. Differential generation of oligodendrocytes from human and rodent embryonic spinal cord neural precursors. Glia. 2004;47:314–324. doi: 10.1002/glia.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A, Nishiyama A, Peterson J, Prineas J, Trapp BD. NG2-positive oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in adult human brain and multiple sclerosis lesions. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:6404–6412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06404.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A, Staugaitis SM, Dutta R, Batt CE, Easley KE, Chomyk AM, Yong VW, Fox RJ, Kidd GJ, Trapp BD. Cortical remyelination: a new target for repair therapies in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2012;72:918–926. doi: 10.1002/ana.23693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew LJ, DeBoy CA, Senatorov VV., Jr Finding degrees of separation: experimental approaches for astroglial and oligodendroglial cell isolation and genetic targeting. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2014;236:125–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway GD, O'Bara MA, Vedia BH, Pol SU, Sim FJ. Histone deacetylase activity is required for human oligodendrocyte progenitor differentiation. Glia. 2012;60:1944–1953. doi: 10.1002/glia.22410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig A, Ling Luo N, Beardsley DJ, Wingate-Pearse N, Walker DW, Hohimer AR, Back SA. Quantitative analysis of perinatal rodent oligodendrocyte lineage progression and its correlation with human. Exp. Neurol. 2003;181:231–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui QL, Fragoso G, Miron VE, Darlington PJ, Mushynski WE, Antel J, Almazan G. Response of human oligodendrocyte progenitors to growth factors and axon signals. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010;69:930–944. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181ef3be4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui QL, D'Abate L, Fang J, Leong SY, Ludwin S, Kennedy TE, Antel J, Almazan G. Human fetal oligodendrocyte progenitor cells from different gestational stages exhibit substantially different potential to myelinate. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:1831–1837. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czepiel M, Boddeke E, Copray S. Human oligodendrocytes in remyelination research. Glia. 2015;63:513–530. doi: 10.1002/glia.22769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darsalia V, Allison SJ, Cusulin C, Monni E, Kuzdas D, Kallur T, Lindvall O, Kokaia Z. Cell number and timing of transplantation determine survival of human neural stem cell grafts in stroke-damaged rat brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:235–242. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel MP, Arnalich Montiel F, Lopez Iglesias P, Blazquez Martinez A, Nistal M. Epiblast-derived stem cells in embryonic and adult tissues. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2009;53:1529–1540. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072413md. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh VA, Tardif V, Lyssiotis CA, Green CC, Kerman B, Kim HJ, Padmanabhan K, Swoboda JG, Ahmad I, Kondo T, Gage FH, Theofilopoulos AN, Lawson BR, Schultz PG, Lairson LL. A regenerative approach to the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2013;502:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nature12647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimou L, Gallo V. NG2-glia and their functions in the central nervous system. Glia. 2015;63:1429–1451. doi: 10.1002/glia.22859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimou L, Simon C, Kirchhoff F, Takebayashi H, Gotz M. Progeny of Olig2-expressing progenitors in the gray and white matter of the adult mouse cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:10434–10442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2831-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doring A, Sloka S, Lau L, Mishra M, van Minnen J, Zhang X, Kinniburgh D, Rivest S, Yong VW. Stimulation of monocytes, macrophages, and microglia by amphotericin B and macrophage colony-stimulating factor promotes remyelination. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:1136–1148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1797-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douvaras P, Wang J, Zimmer M, Hanchuk S, O'Bara MA, Sadiq S, Sim FJ, Goldman J, Fossati V. Efficient generation of myelinating oligodendrocytes from primary progressive multiple sclerosis patients by induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;3:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan ID, Kondo Y, Zhang SC. The myelin mutants as models to study myelin repair in the leukodystrophies. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:607–624. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0080-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnett SB, Rosser AE. Challenges for taking primary and stem cells into clinical neurotransplantation trials for neurodegenerative disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014;61:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy SP, Baranzini SE, Zhao C, Yuk DI, Irvine KA, Kaing S, Sanai N, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Dysregulation of the Wnt pathway inhibits timely myelination and remyelination in the mammalian CNS. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1571–1585. doi: 10.1101/gad.1806309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy SP, Chan JR, Baranzini SE, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Myelin regeneration: a recapitulation of development? Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011a;34:21–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy SP, Harrington EP, Yuen TJ, Silbereis JC, Zhao C, Baranzini SE, Bruce CC, Otero JJ, Huang EJ, Nusse R, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Axin2 as regulatory and therapeutic target in newborn brain injury and remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2011b;14:1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/nn.2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fietz SA, Lachmann R, Brandl H, Kircher M, Samusik N, Schroder R, Lakshmanaperumal N, Henry I, Vogt J, Riehn A, Distler W, Nitsch R, Enard W, Paabo S, Huttner WB. Transcriptomes of germinal zones of human and mouse fetal neocortex suggest a role of extracellular matrix in progenitor self-renewal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:11836–11841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209647109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin RJ, Ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: from biology to therapy. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2008;9:839–855. doi: 10.1038/nrn2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin RJ, Goldman SA. Glia disease and repair-remyelination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015;7:a020594. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin RJ, Bayley SA, Blakemore WF. Transplanted CG4 cells (an oligodendrocyte progenitor cell line) survive, migrate, and contribute to repair of areas of demyelination in X-irradiated and damaged spinal cord but not in normal spinal cord. Exp. Neurol. 1996;137:263–276. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L, Lowell S, Rubin LL, Anderson DJ. Deregulation of dorsoventral patterning by FGF confers trilineage differentiation capacity on CNS stem cells in vitro. Neuron. 2003;40:485–499. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier HO, Evans KA, Volbracht K, James R, Sitnikov S, Lundgaard I, James F, Lao-Peregrin C, Reynolds R, Franklin RJ, Karadottir RT. Neuronal activity regulates remyelination via glutamate signalling to oligodendrocyte progenitors. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8518. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, Paus T, Evans AC, Rapoport JL. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogate N, Verma L, Zhou JM, Milward E, Rusten R, O'Connor M, Kufta C, Kim J, Hudson L, Dubois-Dalcq M. Plasticity in the adult human oligodendrocyte lineage. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:4571–4587. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04571.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman SA, Nedergaard M, Windrem MS. Glial progenitor cell-based treatment and modeling of neurological disease. Science. 2012;338:491–495. doi: 10.1126/science.1218071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorris R, Fischer J, Erwes KL, Kesavan J, Peterson DA, Alexander M, Nothen MM, Peitz M, Quandel T, Karus M, Brustle O. Pluripotent stem cell-derived radial glia-like cells as stable intermediate for efficient generation of human oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2015;63:2152–2167. doi: 10.1002/glia.22882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng MY, Lin ST, Verret L, Huang Y, Kamiya S, Padiath QS, Tong Y, Palop JJ, Huang EJ, Ptacek LJ, Fu YH. Lamin B1 mediates cell-autonomous neuropathology in a leukodystrophy mouse model. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:2719–2729. doi: 10.1172/JCI66737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RA, Patel KD, Goncalves CM, Grutzendler J, Nishiyama A. Modulation of oligodendrocyte generation during a critical temporal window after NG2 cell division. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:1518–1527. doi: 10.1038/nn.3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman MA. Evolution of the human brain: when bigger is better. Front. Neuroanat. 2014;8:15. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi M, Lindsten T, Pleasure D, Itoh T. Differing in vitro survival dependency of mouse and rat NG2+ oligodendroglial progenitor cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010;88:957–970. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BY, Du ZW, Li XJ, Ayala M, Zhang SC. Human oligodendrocytes from embryonic stem cells: conserved SHH signaling networks and divergent FGF effects. Development. 2009a;136:1443–1452. doi: 10.1242/dev.029447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BY, Du ZW, Zhang SC. Differentiation of human oligodendrocytes from pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2009b;4:1614–1622. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JK, Jarjour AA, Nait Oumesmar B, Kerninon C, Williams A, Krezel W, Kagechika H, Bauer J, Zhao C, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Chambon P, Ffrench-Constant C, Franklin RJ. Retinoid X receptor gamma signaling accelerates CNS remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:45–53. doi: 10.1038/nn.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes EG, Kang SH, Fukaya M, Bergles DE. Oligodendrocyte progenitors balance growth with self-repulsion to achieve homeostasis in the adult brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:668–676. doi: 10.1038/nn.3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine KA, Blakemore WF. Remyelination protects axons from demyelination-associated axon degeneration. Brain J. Neurol. 2008;131:1464–1477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A, Dutta R, Wark GM, Hwang SI, Han DK, Trapp BD, Pfeiffer SE, Bansal R. Human myelin proteome and comparative analysis with mouse myelin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:14605–14610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905936106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izrael M, Zhang P, Kaufman R, Shinder V, Ella R, Amit M, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Chebath J, Revel M. Human oligodendrocytes derived from embryonic stem cells: effect of noggin on phenotypic differentiation in vitro and on myelination in vivo. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007;34:310–323. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovcevski I, Zecevic N. Sequence of oligodendrocyte development in the human fetal telencephalon. Glia. 2005;49:480–491. doi: 10.1002/glia.20134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery ND, Blakemore WF. Locomotor deficits induced by experimental spinal cord demyelination are abolished by spontaneous remyelination. Brain J. Neurol. 1997;120(Pt 1):27–37. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SH, Fukaya M, Yang JK, Rothstein JD, Bergles DE. NG2+ CNS glial progenitors remain committed to the oligodendrocyte lineage in postnatal life and following neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2010;68:668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keirstead HS, Nistor G, Bernal G, Totoiu M, Cloutier F, Sharp K, Steward O. Human embryonic stem cell-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cell transplants remyelinate and restore locomotion after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:4694–4705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0311-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyoung HM, Roy NS, Benraiss A, Louissaint A, Jr, Suzuki A, Hashimoto M, Rashbaum WK, Okano H, Goldman SA. High-yield selection and extraction of two promoter-defined phenotypes of neural stem cells from the fetal human brain. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nbt0901-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornack DR, Rakic P. Changes in cell-cycle kinetics during the development and evolution of primate neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:1242–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann T, Miron V, Cuo Q, Wegner C, Antel J, Bruck W. Differentiation block of oligodendroglial progenitor cells as a cause for remyelination failure in chronic multiple sclerosis. Brain J. Neurol. 2008;131:1749–1758. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassmann H, Bruck W, Lucchinetti CF. The immunopathology of multiple sclerosis: an overview. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Gee M, Camicioli R, Wieler M, Martin W, Beaulieu C. Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract evolution over the lifespan. NeuroImage. 2012;60:340–352. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Morrison BM, Li Y, Lengacher S, Farah MH, Hoffman PN, Liu Y, Tsingalia A, Jin L, Zhang PW, Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ, Rothstein JD. Oligodendroglia metabolically support axons and contribute to neurodegeneration. Nature. 2012;487:443–448. doi: 10.1038/nature11314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong SY, Rao VT, Bin JM, Gris P, Sangaralingam M, Kennedy TE, Antel JP. Heterogeneity of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in adult human brain. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 2014;1:272–283. doi: 10.1002/acn3.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Mela A, Guilfoyle EM, Goldman JE. Neonatal and adult O4(+) oligodendrocyte lineage cells display different growth factor responses and different gene expression patterns. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009;87:3390–3402. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JL, Langaman C, Morell P, Suzuki K, Matsushima GK. Episodic demyelination and subsequent remyelination within the murine central nervous system: changes in axonal calibre. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2001;27:50–58. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2001.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JL, Toews A, Hostettler JD, Morell P, Suzuki K, Goldman JE, Matsushima GK. Oligodendrocytes and progenitors become progressively depleted within chronically demyelinated lesions. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;164:1673–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63726-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matalon R, Rady PL, Platt KA, Skinner HB, Quast MJ, Campbell GA, Matalon K, Ceci JD, Tyring SK, Nehls M, Surendran S, Wei J, Ezell EL, Szucs S. Knock-out mouse for Canavan disease: a model for gene transfer to the central nervous system. Journal of Gene Medicine. 2000;2:165–175. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(200005/06)2:3<165::AID-JGM107>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima GK, Morell P. The neurotoxicant, cuprizone, as a model to study demyelination and remyelination in the central nervous system. Brain Pathol. 2001;11:107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei F, Fancy SP, Shen YA, Niu J, Zhao C, Presley B, Miao E, Lee S, Mayoral SR, Redmond SA, Etxeberria A, Xiao L, Franklin RJ, Green A, Hauser SL, Chan JR. Micropillar arrays as a high-throughput screening platform for therapeutics in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Med. 2014;20:954–960. doi: 10.1038/nm.3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Miller RH, Tang W, Lee X, Hu B, Wu W, Zhang Y, Shields CB, Miklasz S, Shea D, Mason J, Franklin RJ, Ji B, Shao Z, Chedotal A, Bernard F, Roulois A, Xu J, Jung V, Pepinsky B. Promotion of central nervous system remyelination by induced differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Ann. Neurol. 2009;65:304–315. doi: 10.1002/ana.21581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JA, Horvath S, Geschwind DH. Divergence of human and mouse brain transcriptome highlights Alzheimer disease pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:12698–12703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914257107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron VE, Rajasekharan S, Jarjour AA, Zamvil SS, Kennedy TE, Antel JP. Simvastatin regulates oligodendroglial process dynamics and survival. Glia. 2007;55:130–143. doi: 10.1002/glia.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron VE, Zehntner SP, Kuhlmann T, Ludwin SK, Owens T, Kennedy TE, Bedell BJ, Antel JP. Statin therapy inhibits remyelination in the central nervous system. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174:1880–1890. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron VE, Boyd A, Zhao JW, Yuen TJ, Ruckh JM, Shadrach JL, van Wijngaarden P, Wagers AJ, Williams A, Franklin RJ, Ffrench-Constant C. M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:1211–1218. doi: 10.1038/nn.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CS, Cui QL, Warsi NM, Durafourt BA, Zorko N, Owen DR, Antel JP, Bar-Or A. Direct and indirect effects of immune and central nervous system-resident cells on human oligodendrocyte progenitor cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2015;194:761–772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]