Abstract

A health literate health care organization is one that makes it easy for people to navigate, understand, and use information and services to take care of their health. This chapter explores the journey that a growing number of organizations are taking to become health literate. Health literacy improvement has increasingly been viewed as a systems issue, one that moves beyond siloed efforts by recognizing that action is required on multiple levels. To help operationalize the shift to a systems perspective, members of the National Academies Roundtable on Health Literacy defined ten attributes of health literate health care organizations.

External factors, such as payment reform in the U.S., have buoyed health literacy as an organizational priority. Health care organizations often begin their journey to become health literate by conducting health literacy organizational assessments, focusing on written and spoken communication, and addressing difficulties in navigating facilities and complex systems. As organizations’ efforts mature, health literacy quality improvement efforts give way to transformational activities. These include: the highest levels of the organization embracing health literacy, making strategic plans for initiating and spreading health literate practices, establishing a health literacy workforce and supporting structures, raising health literacy awareness and training staff system-wide, expanding patient and family input, establishing policies, leveraging information technology, monitoring policy compliance, addressing population health, and shifting the culture of the organization.

The penultimate section of this chapter highlights the experiences of three organizations that have explicitly set a goal to become health literate: Carolinas Healthcare System (CHS), Intermountain Healthcare, and Northwell Health. These organizations are pioneers that approached health literacy in a systematic fashion, each exemplifying different routes an organization can take to become health literate. CHS provides an example of how, even when the most senior leadership drives the organization to become health literate, continued progress requires constant reinvigoration. At Intermountain Healthcare, the push to become a health literate organization was the natural consequence of organizational adoption of a model of shared accountability that necessitated patient engagement for its success. Northwell Health, on the other hand, provides a model of how a persistent champion can elevate health literacy to become a system priority and how system-wide policies and procedures can advance effective communication across language differences, health literacy, and cultures.

The profiles of the three systems make clear that the opportunities for health literacy improvement are vast. Success depends on the presence of a perfect storm of conditions conducive to transformational change. This chapter ends with lessons learned from the experiences of health literacy pioneers that may be useful to organizations embarking on the journey. The journey is long, and there are bumps along the road. Nonetheless, discernable progress has been made. While committed to transformation, organizations seeking to be health literate recognize that it is not a destination you can ever reach. A health literate organization is constantly striving, always knowing that further improvement can be made.

Keywords: Health literacy, health literate organization, organizational assessment, quality improvement, system perspective, organizational change, spread, transformation

1. Introduction

The Roundtable on Health Literacy, sponsored by the U.S. Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, introduced the concept of a health literate health care organization – that is, an organization that makes it easy for people to navigate, understand, and use information and services to take care of their health [1, 2]. This chapter explores the journey that a growing number of health care organizations are taking to become health literate. Readers looking for a “how-to” guide may want to consult the publication, Building Health Literate Organizations: A Guidebook To Achieving Organizational Change [3].

Many organizations would state that making it easier for people to navigate, understand, and use information and services is an organizational priority, but would not describe themselves as health literate. They might, for example, describe that priority as being person-centered or striving for superior patient experiences [4, 5]. The aim of this chapter is not to distinguish health literate organizations from their similarly oriented counterparts. Rather, this chapter’s objective is to trace the movement of the health literacy field towards a systems perspective – one that moves beyond siloed efforts by recognizing that action is required on multiple levels – and to document and learn from implementation experiences of those who have commenced the journey.

This chapter is informed by the framework posited by a participants in the National Academies Roundtable on Health Literacy, which identifies ten attributes of a health literate organization [2]. The organization of this chapter roughly follows the journey that organizations make when they aim to become health literate. After describing health literacy’s emergence as a systems issue, the ten attributes of a health literate organization, and the external drivers of organizational health literacy, the chapter follows a naturalistic path, telling the story of organizational progress as it frequently unfolds. First, it discusses the steps that organizations take when they begin the journey: using health literacy assessment tools and focusing on written and spoken communication. Next, we look at what happens when an organization sets a goal of becoming health literate, covering the following topics: organizational leadership, strategic planning, health literacy workforce and structures, universal awareness and training; patient and family advisory councils, policies, information technology and monitoring, population health, and culture.

In addition to literature cited, the following data sources informed this chapter.

-

Documents and interviews with multiple individuals who work at three systems that have declared becoming health literate as an organizational goal:

Carolinas HealthCare Systems, Intermountain Healthcare, and Northwell Health.

Interviews with twenty organizations that were part of a study on organizational health literacy measurement.

Conference presentations, including those at workshops of the National Academies Roundtable on Health Literacy and the Health Literacy Annual Research Conference.

Site visits to health care organizations while making grand round presentations.

2. Emergence of Health Literacy as a Systems Issue

The field of health literacy was spawned by research that found that people with limited literacy skills were at risk of poor health and health care [6]. Many articles in the 1990’s documented that individuals with low literacy are less likely to use preventive services or adhere to treatment, while they are more likely to be hospitalized and be in poor health [7]. It quickly became clear, however, that the problem was not constrained to the population of the poorest readers. Studies revealed that written health materials, such as patient education materials, exceeded the average person’s ability to read and understand them [8–12]. The finding from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy that only 12 percent of the population could complete an array of tasks requiring comprehension of real world written health materials consolidated the growing sense that the literacy demands of health information had to be reduced [13].

The first decade of the 21st century saw health literacy expand beyond its roots in written communication to include spoken communication [14]. In addition, there was an ever-growing recognition of challenges associated with accessing services and navigating among facilities [15], providers, and settings. As a result, health literacy frameworks and calls to action came to incorporate the need to address the numerous complexities people face in accessing health care and managing their health [16–18]. Within this broader view of health literacy as a “systems” issue, it was understood that even the most skilled, well-intentioned clinician cannot single-handedly overcome the health literacy barriers people face [19]. Rather, as had already occurred in the patient safety arena [20], health systems rather than individual clinicians have come to be held responsible for addressing the underlying problem.

The importance of systems in addressing health literacy deficits was articulated in the 2004 landmark health literacy report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (then known as the Institute of Medicine) [21]. It referenced the 2001 Crossing the Quality Chasm report that specified, among other things, that systems of care should be redesigned such that information available to patients and families allows informed decision making [22].

Paasche-Orlow and colleagues were among the first to offer a vision of how health care systems should transform themselves to respond to health literacy challenges [23]. In 2006 they advocated for reorganizing health care to make systems patient-centered and pointed to the Care Model as a foundation[24]. This concept was later expanded upon with the development of the Health Literate Care Model, which identifies specific health literacy strategies that should be integrated into the Care Model to improve patient engagement in prevention, decision-making, and self-management [25]. Paasche-Orlow and Wolf also pointed to the complexity of the health care system and its acute care orientation as factors driving poor health outcomes [26].

Since 2010, the emphasis on the need for organizational, rather than clinician-level, remediation has grown. The Joint Commission called for organizations to make effective communication a priority [27]. The National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy, published in 2010, called upon health care executives to: train all staff; establish formal mechanisms to review all written information for patients; include members of patient communities in organizational assessments and health literacy improvement efforts; integrate health literacy and cultural and linguistic competence audit tools, standards, and scorecards into all quality process and performance improvement activities and metrics; and create welcoming, easy-to-navigate, shame-free environments [28]. A striking example of the shift toward a systems approach is the National Academies Roundtable on Health Literacy’s adoption of a new mission statement in 2015 to include a vision of “a society in which the demands of the health and health care systems are respectful of and aligned with people’s skills, abilities, and values” [29].

3. Attributes of Health Literate Health Care Organizations

To help operationalize the shift to a systems perspective, members of the National Academies Roundtable on Health Literacy set out to define the attributes of a health literate organization. The aim of the Roundtable was to create the health literacy equivalent of the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (the CLAS Standards) [30]. The CLAS Standards had been issued by the DHHS’ Office of Minority Health in 2000 and had gone on to become the template for organizations seeking to be culturally and linguistically competent. Toward this end, the Roundtable commissioned a white paper, held a workshop, and ultimately published an IOM Perspective that resulted in the forging of a set 10 attributes that exemplify health literate health care organizations [1, 2, 31]. (See Table 1.) In the years following its publication, the Ten Attributes of Health Literate Health Care Organizations has been used as a framework for both an assessment tool and a guidebook on building health literate organizations [3, 32]. It has served as a guidepost for organizations wishing to transform themselves to meet health literacy goals and has influenced health literacy efforts internationally [33, 34]. We will see later in this chapter how two large health care systems in the United States adopted the ten attributes framework as their organizing principle for health literacy improvement.

Table 1.

Ten attributes of health literate health care organizations

A health literate health care organization:

|

In operational terms, being a health literate organization means moving beyond the project-based improvement mindset. For example, an organization that only addresses health literacy for one population (e.g., people with heart disease) is not a health literate organization. An organization can even have several health literacy improvement projects without being health literate. For an organization to be truly health literate, health literacy has to pervade the organization and be integral to all operations. As long as health literacy is seen as an add-on, struggling for a seat at the table, organizations will not be health literate.

4. External Drivers of Organizational Health Literacy in the United States

The shift from fee-for-service to value-based payments in the United States has buoyed health literacy as an organizational priority. Financial rewards for positive clinical and patient satisfaction outcomes have encouraged the adoption of population management methods and focused attention on the patient experience. Addressing health literacy – by increasing patients’ understanding of health information, ability to get needed services, and self-management capabilities – can help health care organizations meet both clinical and patient satisfaction outcomes. Laws passed by the U.S. Congress in the second decade of this century have accelerated the movement towards value-based payments. Payment reform under the U.S. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the U.S. Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act has been particularly important in re-shaping organizational priorities in the United States.

4.1. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)

In 2010, U.S. Congress passed the ACA, which includes provisions to promote a redesign of the health care delivery system [35]. Following passage of the ACA, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS – part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) made payment changes that shifted health care organizations from to focusing purely on the volume of services delivered to rewarding efficiency (through shared savings) and quality. More specifically, through Alternative Payment Models, such as Accountable Care Organizations, U.S. providers have incentives to actively manage the health care of an entire population of Medicare2 beneficiaries rather than reactively delivering acute care for episodes of illness.

Similarly, through the Medicare Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) Program, Medicare payments now depend in part on quality metrics, including patient experience surveys, readmission rates to hospitals, and clinical measures. For example, starting in federal fiscal year 2015, CMS reimbursement changes provided hospitals with incentive to reduce 30-day readmissions for patients with targeted conditions. This focused a great deal of attention on improving patient education and discharge process to ensure that patients with targeted conditions stayed away from the hospital for at least a month. Furthermore, for the first time hospitals are being paid, in part, based on their post-hospital outcomes and how patients rate the care they receive. Notably, patients’ ease of understanding of their doctors and nurses is one of the metrics on which patients are asked to rate their experience.

Formerly health care organizations had patient relations departments focused on attracting and retaining patients. The new approach is to focus more on improving patients’ experiences of their care. This in turn has given rise to a new profession – the Patient Experience Officer [36]. Patient Experience Officers, with their mission to sensitize the delivery system to patients’ experiences, are a natural ally for health literacy.

The ACA also gave a boost to the patient-centered medical home model (PCMH) that already had been gaining currency in primary care circles. Accreditors that issued standards for organizations seeking certification as PCMHs required clear communication, enhanced access and coordination, patient education and self-management support, and culturally and linguistically appropriate care [37]. With the ACA’s promotion of patient-centered care, internal health literacy advocates had another lever for health literacy improvement.

4.2. Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA)

The passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) by the U.S. Congress spread value-based purchasing further. Starting in 2017, U.S. health care providers that are not participating in Advanced Alternative Payment Models are scheduled to participate in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) [38]. Like the above-described HVBP Program, MIPS will reward or penalize physicians based on their outcomes, including patient experience. If implemented, MIPS is likely to do for outpatient care what HVBP Program did for hospitals: focus attention on patients’ experiences of care. In a 2016 environmental scan of organizations undertaking organizational health literacy improvement, the most common form of monitoring was found to be tracking patient experience data, either through CAHPS® or other surveys [39].

MIPs will also give incentives to address health literacy from a population health perspective. Previously, U.S. health care organizations had little financial incentive to make sure patients understood how to care for themselves and maintain their health. The system was geared toward delivering as many billable services as possible. Following the dictates of professionalism, which obliges clinicians to help patients manage their conditions, came at a cost. As the population became healthier, revenues would decline due to a reduction in the number of procedures or office visits. With MIPS and the expected increase value-based payments by private health plans in the U.S., investments to make health information more understandable and ensure that patients can navigate the health care system might actually pay off.

In sum, U.S. health care organizations are realizing that being held accountable for outcomes and satisfaction means they need to do a better job of engaging patients. Health care systems will have to depend on individuals becoming involved in their health and health care if they are to achieve such goals as controlling high blood pressure and blood sugar. Addressing health literacy is fundamental to engaging patients; people cannot actively participate in their health care and take responsibility for their health if they are stymied by the complexity of health information and health care systems [25].

5. Early Days: Commencing the Journey to Become a Health Literate Organization

Payment reform provides an incentive to organizations to address health literacy, but does not tell organizations how to become health literate. Organizations usually start out with limited health literacy projects before they make a decision to address organizational shortcomings in a systematic fashion. They may take advantage of opportunistic innovation, making inroads where they can, when they can. Typically, it is only after they make some progress that organizations can make the leap from project-based quality improvement to system transformation. This section reviews how systems have taken these first steps, including undertaking organizational assessments of existing policies and operations and improving written communication, spoken communication, and physical or virtual navigation.

5.1. Organizational Health Literacy Assessment

Organizational health literacy assessments are useful in stimulating improvement activity [40] and serve as powerful tools to:

promote awareness and discussion of current practices,

identify strengths and areas for improvement,

gain consensus for prioritizing health literacy interventions, and

stimulate health literacy strategic planning.

Organizational health literacy assessment tools have been developed for a range of health care settings. (See Table 2.) The first health literacy assessment tool, the Health Literacy Environment Review, targeted hospitals and health centers [41]. It was closely followed by the publication of an audit tool for pharmacies [42]. These assessment tools, and others that followed for primary care practices health plans, and health and social service organizations were designed to be used for internal improvement purposes rather than by outside auditors for accountability purposes [32, 43–46].

Table 2.

Organizational health literacy assessment tools

| Tool and Publication Date | Target Audience | Domains | Assessment Methods | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Literacy Environment Review (2006) | Hospitals and Clinics |

|

Self ratings (Done, Needs Improvement, Done Well) |

|

| Pharmacy Health Literacy Assessment Tool (2007) | Pharmacies |

|

|

|

| Organizational Communication Climate Assessment Toolkit (2008) | Hospitals and Primary Care Clinics |

|

|

|

| Primary Care Health Literacy Assessment (2010, 2015) | Primary Care Practices Clinics |

|

Self ratings (Doing Well, Needs Improvement, Not Doing, Not Sure/Not Applicable) |

|

| Health Plan Organizational Assessment of Health Literacy Activities (2010) | Health Plans |

|

Self ratings (Tailored response categories) |

|

| Enliven Organisational Health Literacy Self-assessment Audit Resource (2013) | Health and Social Service Organizations | Each of the 10 attributes of a health literate organization is a domain (See Table 1.) | Checklist |

|

Organizations have often adapted assessment tools, mixing and matching items from different assessment tools or changing the wording of items to better suit their environment [47]. They have used frameworks (such as the ten attributes of a health literate health care organization), home grown surveys of staff or patients, chart audits, patient tracers (shadowing a patient during a visit or inpatient stay), rounding on units, sampling patient education materials, and other means to gain intelligence on how health literate the organization is [48]. Some systems have used more rigorous patient experience surveys to flag a problem, and then followed up with these less scientific methods to peer inside the black box and pinpoint its source.

While these assessment tools were all pilot-tested for overall usability, none of these tools was validated as being reliable to measure improvement. Even the American Medical Association’s Communication Climate Assessment Tools, which underwent rigorous testing to determine their validity, did not establish their ability to measure change over time [49]. Nevertheless, organizations have used repeated administration of assessments to measure their progress.

Health care organizations need to be mindful of the limitations on appropriate uses of assessment instruments and the complexities associated with correctly interpreting their results. For example, systems have reported a lack of consistency between numerical ratings and subjective comments on an assessment instrument, which may indicate a failure of respondents to understand the meaning of a question or a social desirability bias.3 Declines in self-assessment scores might actually signal increased sensitization to organizational deficiencies rather than changes in practice [50]. Finally, staff perceptions of organizational health literacy could increase without an actual increase in the use of health literacy strategies [51].

Probably more important than the particular tool chosen to guide the assessment activity is the process of assessment. Features of successful health literacy assessment processes have included:

High commitment level. Establishing a dedicated work group with senior members and regular meetings is critically important.

Adequate time. It has taken large systems up to a year to complete both the internal and external scans.

Hiring consultants. Organizations frequently have not had in-house health literacy expertise and have sought external specialists to guide their assessment.

Harnessing patient’s stories. Understanding how patients see the organization and move through the system is critical to both figuring out where to target improvement and gaining buy-in for health literate changes.

Broad engagement. Systems have sent assessment tools throughout the organization, either to be completed by key individuals or collectively in various departments or facilities.

Strategic deployment. Especially at the outset, systems have conducted assessments in a few domains that demonstrated a critical need for action.

These insights on conducting assessments are generic and could apply to any quality improvement effort. It is the assessment topics that are specific to health literacy. Common to virtually all the health literacy organizational assessment tools are domains on written communication, spoken communication and physical or virtual navigation. These are frequently the next steps on the journey to become health literate.

5.2. Focus on the Written Word

Health literacy has often been incubated in committees or offices responsible for patient education materials. This reflects both the historical concern with individuals with limited literacy and the narrow connotation people have with the term “health literacy” with reading and writing. This branch of health literacy improvement has coincided with the plain language movement, which had its antecedents in frustration first voiced during the 1950’s with confusing regulations and other bureaucratic-sounding publications of the federal government [52]. The plain language movement started to get traction in agencies of the Department of Health and Human Services around the same time that health literacy came into prominence with the publication of health literacy objectives for Healthy People 2010 [53].

Guides to making written health care information easier to understand date back to the earliest days of the health literacy field [54, 55]. Over time, guidance has become more sophisticated and begun to address online written materials [56, 57]. Automated readability formulas that roughly gauge the reading demands of written materials by counting up syllables in words and words in sentences to estimate grade level are widely used to signal that reading demands may be too high. Commercial products now detect reading level and stylistic deficiencies, such as use of the passive voice, and suggest alternatives. Three new tools involve quantitative measures of the use of health literacy principles, understandability, and actionability – the Health Literacy INDEX, the Clear Communication Index (CCI), and the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) [58–60]. Many organizations use these tools as part of their strategy to ensure people understand their written materials.

No single approach has emerged as the most effective for improving written materials. Some organizations have relied on mainstream vendors that, in response to demand, promote their materials as following health literate principles. Others have turned to niche vendors who specialize in easy-to-understand, multi-lingual materials. Still others have produced their own materials in-house, having found that the patient education materials they have purchased do not meet their standards.

Even organizations that do purchase patient education materials often have to also produce many of their own documents. With input from stakeholders, large health systems have established processes for creating and approving of written materials. The processes themselves frequently involve a wide range of representatives from throughout the system, such as from legal, marketing, accreditation, and safety departments; physician groups; and facilities. The resources required to manage written materials generally exceed what systems have allocated for the task. One strategy to reduce the workload of centralized editorial staff is to increase the quality of submitted materials. Organizations have accomplished this by providing health literacy training and tools (such as plain language glossaries, commercial software products, and style manuals) to writing staff throughout the system. Nevertheless, editorial staff frequently report having to prioritize important documents and an inability to review and update materials as frequently as their policy dictates.

Many organizations have recognized the importance and value of incorporating feedback from patients and families into their review process. Approaches have included getting feedback from general Patient and Family Advisory Councils, using committees of patient and families formed specifically to review materials, holding focus groups with diverse and disadvantaged members, and testing materials for comprehension with individuals with low literacy. One key source of confusion and frustration for many patients has been the bill for services [61]. Systems have found that revamping their bills to make them more understandable to be a huge undertaking, involving designing prototypes, gathering consumer feedback, and making information technology changes in the bill production process.

Despite all these labor intensive efforts, there is a segment of the population for whom written material, however simplified, will still be incomprehensible. The most recent attempts to serve these populations involve technological alternatives. For example, some systems provide inpatients with multi-lingual, interactive edutainment systems. These systems, made available on a television screen or computer tablet, allow patients to learn about their conditions and how to take care of themselves through video and other audio-visual content, and can even test learning and allow users to ask questions. In addition to overcoming literacy and language barriers, such systems are showing potential to reduce the amount of time clinicians have to spend educating patients and even reduce the length of inpatient stays. High-tech cannot completely replace high-touch for some patients who need extra help, but interfaces designed specifically for those with limited literacy and computer skills can be easy to use and well-liked by vulnerable populations [62].

Most organizations that have worked hard to reduce the literacy demands of their materials will acknowledge that these improvements are incremental and further work is needed. Moreover, as has been said earlier, what distinguishes organizations that have embarked on the health literate journey is that they have issued policies and set up structures to standardize processes across the board. With regards to written materials, adopting a system approach has included many, if not most of the following.

Establishing accountability and requiring consistency for written materials system-wide

Setting standards for user-centered materials for in-house production and vendor purchase

Instituting processes for taking inventory, prioritizing, reviewing, and updating written materials

Establishing policies, such as prohibiting materials that have not gone through the editorial process and used professional translators to be uploaded into information systems.

Adhering to a schedule to re-assess materials

Making materials easily accessible by including them in electronic health records (EHRs)

5.3. Focus on Spoken Communication

Like making written materials easy to understand, effective interpersonal communication is an attribute of health literate organizations that receives early attention. Improving spoken communication is a particularly important health literacy strategy for meeting the needs of non-readers. A study reporting that people immediately forget half of what they are told, and inaccurately recall half of what they retain, has been a rallying cry for efforts to improve health literacy [63]. As a result, health literacy training has often been directed at improving the spoken communication skills of the clinical team, for example by emphasizing speaking slowly, using plain language, limiting the amount of information given at one time, and encouraging questions. Role playing is a very popular form of teaching spoken communication skills. As systems spread health literacy beyond the clinician-patient interactions, they have training to all staff who interact with patients, from registration to billing staff.

Unlike other communication enhancement efforts that might focus on building clinician-patient relationships or having difficult conversations, efforts to improve health literacy focus on improving understanding [5, 64]. Confirming understanding has become a staple of organizations’ health literacy improvement strategies, and teach-back – asking people to state in their own words what they have been told – is its poster child. Teach-back and the show-me method (asking people to demonstrate how they will do something at home) are acclaimed as the only way to truly confirm understanding. As one of the few health literacy strategies with an evidence base that links it directly to self-management and outcomes [65–68], teach-back has been the subject of training programs [14, 69], deemed a safe practice with regard to informed consent by AHRQ and the National Quality Forum, and promoted by accreditation organizations [27, 70, 71].

Methods of stimulating conversation are also being used. Some organizations are using or adapting Ask Me 3®, a program to encourage patients to get answers to three questions: 1) What is my problem? 2) What do I need to do? 3) Why is it important for me to do this? While some organizations use the National Patient Safety Foundation’s Ask Me campaign materials (e.g., posters, notepads), others use Ask Me 3 as a guide for providers to make sure providers give information such that patients can answer the three questions by the end of a visit.

Systems will sometimes allow for local tailoring of improvement efforts. This can spark innovation and encourage implementers to own the changes they make. An example of a creative, home grown way of promoting clear spoken communication was to use white boards to write down complex language staff caught teammates using, along with plain language alternatives. In contrast, a more regimented approach was taken by a system that wanted to ensure all patients received exactly the same education during inpatient stay; it developed a specific curriculum and required nurses to document when each segment was taught.

5.4. Navigating Facilities and Systems

Navigation was first raised as a health literacy problem out of concern over the complexity of health care facilities and their poor signage [72]. Large systems responding to this challenge have gone beyond using more recognizable terminology on their signs (e.g., x-ray instead of radiology). Creative tactics have included using color coded pathways, standardizing plain language directions, having volunteer escorts, posting directions in commonly used languages, training all staff to be on the lookout for the puzzled expressions of people who are lost, and using golf carts to transport individuals across large campuses. Navigation apps to leverage mobile technology are on the horizon. Such navigation efforts are often aligned with more general initiatives to adopt a customer service orientation.

Navigation in health care also refers to negotiating a fragmented system – coordinating among care providers and managing transitions. The professions of cancer care navigators, community health workers, care coordinators, and case managers are all dedicated to guiding people through the maze of health services that patients must access. These programs frequently target vulnerable populations such as those with limited English proficiency or high disease burden. In addition to steering patients through the health care system, navigators frequently attend to non-medical needs, link them with resources in the community, and teach them the skills to navigate for themselves. These programs guard against the neediest from falling through the cracks of the system.

Organizations whose goal is to be health literate, however, have to relieve the coordination burden for all patients. One method for doing so is to “close the loop” when referring patients from one provider to another. If a warm handoff (i.e., a personal introduction with a transfer of responsibility for follow-up) cannot be achieved, the referring provider will follow up with the patient to confirm that a connection was made. Other efforts to make care more seamless have included making specialized referral agreements among providers, for example for drop-in mammograms. Policies designed to lower the demands on patients are sometimes used, such as not asking patients to convey medical information from one provider to another. Most organizations, however, would acknowledge that they are not where they would like to be on this aspect of being health literate.

Finally, as penalties for excess readmissions have kicked in, systems have given particular attention to transitions from hospital to home, which are among the most fraught and challenging to navigate. For systems aiming to be health literate, the focus on the discharge process has triggered a broader examination of how inpatients are educated. This in turn fueled efforts to improve both written and spoken communication, and to formally structure the education process. Additionally, the strategies of making post-discharge phone calls and ensuring patients connect with outpatient clinicians have grown popular.

6. Maturation: Scaling Up and Institutionalizing

As was noted at the outset of this chapter, when an organization sets a goal of becoming health literate, it replaces fragmented quality improvement activities with a systematic and comprehensive approach. Health care organizations do not start the journey in a single place, and the journey is not linear. Headway is made in spurts, losing ground is not uncommon, and the journey is a lengthy one.

The move from health literacy quality improvement toward transformation into a health literate organization entails:

the highest levels of the organization embracing health literacy,

making strategic plans for initiating and spreading health literate practices,

establishing a health literacy workforce and supporting structures,

raising health literacy awareness and training staff system-wide,

expanding patient and family input,

establishing policies,

leveraging information technology and monitoring policy compliance,

addressing population health, and

shifting the culture of the organization.

This section examines how health care organizations aspiring to become health literate have institutionalized their health literacy activities.

6.1. Organizational Leadership

When C-suite officials (e.g., Chief Executive Officer, Chief Nursing Officer, Chief Medical Officer, Chief Experience Officer) have championed health literacy, it is usually because health literacy goals are closely aligned with the organization’s mission, goals, and business imperatives. They set their sights on becoming health literate because they view it as instrumental to achieving important organizational priorities such as:

providing person-centered care and patient experience,

engaging patients,

ensuring patient safety (e.g., medication safety and readmission reduction),

reducing disparity reduction (e.g., language assistance, cross-cultural communication), and

containing cost.

A sign that health literacy has become entrenched is when it is viewed a means to an end rather than another thing to do. Even mission-driven organizations have considered the business case for health literacy, however, justifying doing the right thing by linking it to obtaining a larger market share or reducing costs. Furthermore, with systems worried about staff burnout and change fatigue, organizational leaders have to see health literacy as a new and better way of doing business.

In some organizations, there are silos of health literacy activity but a lack of leadership to integrate them into a unified force for change. Organizational leaders need to not only communicate the importance of health literacy at the launch of a holistic improvement program, but also to be stalwartly and visibly supportive and attentive throughout implementation and maintenance phases. They have done so by serving on oversight committees, reviewing metrics of success, and making resources available as needed.

6.2. Strategic Planning

Systems leading the pack have engaged in strategic planning to become health literate. Organizational assessments, discussed earlier in this chapter, are a necessary step in strategic planning. Strategic plans, however, go farther than plugging some of the gaps identified by assessments. Strategic plans include concrete goals across multiple health literacy domains and spell out precisely what actions are going to be undertaken to achieve these goals, who will undertake those actions, and how accomplishments will be measured. Inherent in the strategic plan, therefore, is a logic model for how change will happen and which outcomes will be achieved.

Systems that reached the stage of conducting health literacy strategic planning generally have had a foundation in both continuous improvement and intra-organizational spread of innovation. Varied methodologies have been used, sometimes in combination. These have included use of key driver diagrams [73], quality improvement testing cycles [74], SWOT analyses (analyzing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) and Lean A3 problem solving. What has mattered has not been the choice of methods, but rather the experience in improvement and change management, which has provided an infrastructure for health literacy advancement.

6.3. Health Literacy Workforce and Structures

While there is no single recipe for becoming health literate, a key ingredient in all successful efforts is the designation of staff to be responsible for health literacy as all or part of their jobs. An organization cannot, however, become health literate if a single health literacy manager or coordinator in a large system is expected to do all of the heavy lifting. Thus, systems truly committed to becoming health literate typically have established structures that assume responsibility for health literacy. These have sometimes taken the form of task forces or councils established specifically to ensure that health literate policies and practices are being followed. Often the responsibility for health literacy has been overlaid on existing quality improvement or patient safety functions. By contrast, in many not-yet-fully-health-literate organizations, health literacy staff are relatively isolated internal advocates, accumulating small victories without shifting the orientation of the organization.

The success of these important structures – and of organizational literacy efforts more generally – depends on support from health literacy champions throughout the organization. Beyond the organizational leaders mentioned earlier, these include both formal health literacy liaisons and staff who have more informally become standard bearers for health literacy in the course of doing their jobs. For example, patient experience staff may take on the responsibility of raising health literacy issues as they sit on operational committees.

6.4. Universal Awareness and Training

Training programs have ranged from across-the-board training to targeting particular facilities or professions. Large systems and hospitals sometimes start by training nursing staff, since they often have less direct control over physicians and physicians are viewed as more recalcitrant [48]. Health care systems try to strike a balance between the ability to reach a wide audience using online formats with a more intensive in-person approach. Key to such efforts is a combination of system and local leadership underscoring the importance of addressing health literacy and a boots-on-the-ground strategy with local trainers and coaching.

To achieve training goals, adult learning approaches, such as using videos and interactive content, are common. While individuals and small organizations typically use nationally available training materials [44, 75, 76], large systems frequently only consult them and then customize their own programs. Some systems have established professional competencies for attainment of health literacy knowledge, attitudes, and skills.

Systems that have reached more mature levels of health literacy are implementing health literacy training that is:

Universal – Everyone in the organization gets awareness and skills training.

Verifiable – Procedures are in place to record when training is completed.

Recurrent – Training begins with new employee orientation and is refreshed on a regular schedule (e.g., annually).

Remedial – Extra training is targeted to those who can benefit the most from it.

Fortified – Train-the-trainer models use middle management who can reinforce the training and the importance of being health literate (e.g., staff meetings, huddles, newsletters).

6.5. Patient and Family Advisory Councils

Patient and Family Advisory Councils (PFACs) originated in the 1990s in recognition that consumer input into policy and program development was critical to implementing family-centered care [77]. By 2016, 2,000 hospitals had launched a PFAC, and PFACs have erupted in other health care settings as well. Organizations like the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care and, more recently, the Beryl Institute have created resources and training to spur and prepare organizations to create and engage with PFACs [78].

PFACs are a chief avenue for including populations served in the design, implementation, and evaluation of health information and services, as called for by the ten attributes of health literate organizations. PFACs, however, tend to attract participants who, for the most part, have adequate health literacy and English proficiency. Organizations on the health literacy journey have been challenged in engaging more disadvantaged populations. Some organizations have especially reached out to these populations, providing them with training and supportive services that allow them to effectively participate in PFACs. Organizations have also supplemented PFACs by holding focus groups with these populations. This approach has the benefit of drawing out people who might not be vocal on a PFAC, but falls short of engaging these populations fully as partners in the formation of a health literate system.

6.6. Policies

Organizations have promulgated and enforced a variety of policies as a way of standardizing the delivery of care. Health literacy policies generally have reflected a universal precautions approach to delivering health literate care, one which assumes that every individual is at risk of misunderstanding and benefits from clear communication and uncomplicated care pathways. The following are illustrations of common types of health literacy policies:

All patient education materials will go through reviews by editors and patient volunteers. Readability guidelines and health literacy principles will be followed.

Only qualified interpreters will be used to communicate with patients with limited English proficiency.

Patients will not be discharged until they can teach-back the signs of deterioration and what to do about them, as well as how to follow discharge instructions.

Clinicians must ask patients to show how they will perform self-management activities, such as wound care.

Patient education and successful knowledge checks will be documented in the EHR.

All new employees will complete health literacy training within the first 30 days of employment.

Clinicians will refer patients who meet specified criteria to navigators.

Follow-up calls will be made to patients who fail to show for an appointment.

Referring clinicians will provide all relevant information.

All patients will be offered help with forms.

Policies are not always precise, but can give cues regarding expected behavior without detailing what that means. Lack of precision is sometimes necessary to permit flexibility that lets the policy fit into local work flow and culture. For example, a system might issue a directive to “treat patients with respect” or “encourage patients’ questions” but leave open which strategy to use to achieve the stated goal. Vagueness in policy statements become problematic, however, when people are uncertain about how to comply with the policy. For example, hospitals with ambiguous informed consent policies left staff confused about their appropriate roles in the process [79].

While policies are used to drive change, systems are sometimes reluctant to issue a policy that substantially alters current practice. In part, this is out of a concern that accrediting organizations will deem them to be out of compliance with their own policies. Formalization of a policy is therefore sometimes a mark of completing change rather than triggering it.

6.7. Information Technology and Monitoring

Organizations pursuing health literacy try to hardwire it into their information technology (IT). This can be challenging and requires that top leadership prioritize changes needed to support health literacy over other changes that may be in their IT department’s queue. Health literate IT changes fall into two categories: those that make it easier to deliver health literate care, and those that document that health literate care has been given.

Examples of IT fixes that make it easier to get patients the care and information they need include: purging the IT system of unauthorized documents and closing back doors used to post materials that have not gone through the approval process; creating standard order sets of health literate materials that save clinicians the trouble of searching for them; and giving prominence to actionable information, such as displaying a patient’s preferred language at the top of every page.

Systems have struggled with the documentation of health literate care. To create useful data, documentation must be standardized in the EHR, which usually requires creating new data entry fields. Organizations have frequently opted for check boxes that get ticked when the activity occurred (e.g., the patient was taught something, the patient was able to teach it back), despite the danger of gaming the system. Systems think that requiring an entry with the date and time of completion and sign off by supervisors minimizes false entries. Furthermore, requiring such documentation was thought to communicate health literacy expectations to staff, and at a minimum allowed the identification of locales that did not even bother to check the box.

Systems, however, have also relied on means other than self-report to assure compliance with policies, such as using other data sources for verification (e.g., use of interpreter services) and requiring observations of the activity. For example, nurse managers in one system verified that white boards were updated and discussed using a bedside shift report with observation checklist. Observations were made twice a week unless performance is poor, in which case daily checks were made.

6.8. Population Health

Some systems have addressed health literacy by targeting particularly disadvantaged geographic areas and, in doing so, attended to broader challenges that affect population health. In these instances, the system established alliances with community organizations, sometimes taking advantage of existing coalitions. Recognizing that individuals in these communities, especially those with limited health literacy, face a host of barriers to achieving optimal health outcomes, these systems worked to make sure residents connected with help in obtaining insurance coverage, affording medicines, obtaining employment, accessing healthy food, and getting basic adult education. While such efforts fall outside of some definitions of health literacy, addressing the social determinants of health by improving supportive systems for patients is considered part of taking health literacy universal precautions [43].

6.9. Culture

Even with policy changes and significant investments in training, transformation will not occur or endure if it goes against organizational culture [80]. Systems that have had to undergo culture change to routinize new health literate practices have recognized that culture change is something that has to be shaped over time. Fortunately, health literacy found an affinity with efforts to create a more person-centered culture. More specifically, health literacy has been compatible with cultural changes aimed at patient engagement, cultural and linguistic competence, and providing a medical home.

Systems striving to be health literate have recognized that culture change requires a multi-prong approach. This has included defining unacceptable behavior (e.g., trying to “get by” without an interpreter for a patient who is not proficient in English) as well as required behavior (e.g., having a friendly, helpful demeanor), monitoring whether the changes had been made, and supplementing training with constant reinforcement from leadership [81].

It is hard to measure whether cultural change has been successful. Systems have used mixed methods, such as employee surveys and rounding, to gauge the impact of their efforts. Often progress can be seen in subtle changes in behavior that are not formally measured. For example, in one hospital that used training modules with the slogan “Make informed consent and informed choice,” the change lead noted, “When we began to hear clinicians utter the words ‘informed choice,’ we knew we had made headway.”

7. The Journey: Three Organizations’ Efforts to Become Health Literate

Driven by mission as well as pragmatic considerations, an increasing number of organizations are commencing the journey to become health literate organizations. This section highlights the experiences of three organizations that have explicitly set a goal of becoming health literate: Carolinas Healthcare System, Intermountain Healthcare, Northwell Health [82–84]. These organizations are not typical. They are pioneers that approached health literacy in a systematic fashion, each exemplifying different routes along the journey to organizational health literacy. The information in each profile has been selected to highlight different aspects of each of their journeys. An approach may be described in one profile and not another even though both organizations followed a similar approach.

7.1. Carolinas HealthCare System: Health Literacy Top Down and Through and Through

Carolinas HealthCare System (CHS) is a Charlotte-based non-profit system with 60,000 employees and an annual budget of more than $7.7 billion. It is comprised of more than 900 care locations, including academic medical centers, hospitals, physician practices, surgical and rehabilitation centers, home health agencies, urgent care clinics, and other facilities.

Health literacy was ushered in as an organizational priority by the Executive Vice President/Chief Medical Officer (CMO). The CMO intuitively understood the importance of addressing health literacy to achieve patient-centered care and patient safety, and was influenced by the fact that another system (Iowa Health Systems) was working to improve health literacy.

The CMO set into motion actions that led to health literacy becoming a vital part of CHS’ work:

He asked the marketing department to conduct research into low literacy in Charlotte and how it affected patients and CHS financially.

He obtained buy-in from the Board of Directors, which consisted of the heads of all the facilities owned by CHS, by engaging nationally-known health literacy scholar Dr. Darren DeWalt to win their hearts and minds.

He established a system-wide Health Literacy Task Force (HLTF) with representation from all 25 CHS facilities. Co-led by the Director of Performance Enhancement of CHS’ internal consulting team and the Director of CHS’ Center for Advancing Pediatric Excellence who had QI expertise, the HLTF was charged with identifying ways to address health literacy at CHS.

Over a nine-month period, the HLTF educated itself and hashed out an approach to pursue organizational health literacy. The result was CHS’ first health literacy initiative – a one-year learning collaborative. (See Box 1.) Results at the end of the collaborative showed improvement on most of nine measures. Participants were charged with extending health literacy strategies across the system. A year later, however, a survey revealed that health literate strategies had not yet been extensively adopted.

Box 1. Health Literacy Learning Collaborative.

25 facilities across the continuum of care and their affiliated ambulatory practices

Targeted non-physician employees, chiefly nurses

2-day learning session

Plan-Do-Study-Act QI cycles

-

Change package (based on prototype of the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit):

30 changes, 11 mandatory

Mandatory monthly reporting on 9 measures

Health literacy efforts at CHS were reinvigorated by the arrival of a Chief Nurse Executive. She, together with the co-Chairs of the HLTF and the CHS Management Company, strategized about how to spread health literacy practices throughout CHS. Rather than try to spread the entire health literacy collaborative change package, they opted to focus on the spread of two high-leverage changes– teach-back and Ask Me 3. The initiative, called TeachWell (see Box 2), proposed to spread these changes to all facility-based nurses in CHS – over 10,000 nurses – as well as to all employees at the 25 ambulatory faculty practices that were affiliated with CHS hospitals.

Box 2. TeachWell Features.

Focus on spoken communication: teach-back & Ask Me 3

Playbook: implementation guide with tools that drew on already established approaches (e.g., Kaiser Permanente’s Nurse Knowledge Exchange Plus program and the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit)

-

Implementation infrastructure at each facility:

Facility/Business Unit Champions

Project Advisors

Small Team Leaders

Small Teams

Mandatory training for all nurses, who sign pledges to use health literacy skills

Re-enforcement through staff meetings, daily huddles, and the use of communication self-assessments, teach-back observation forms, and tracking logs.

Measures of observed use of health literacy strategies reported to CHS senior leadership

A 15-member TeachWell Steering Committee developed a structure for the implementation effort that included enlisting a top manager at each facility as a Facility/Business Unit Champion and one or two staff at each facility as Project Advisors to oversee facility-wide implementation. CHS encouraged each facility to assess their health literacy practices by providing a variety of assessment tools. Each small team in CHS facilities used small tests of change to refine their plans before rolling out the training to all nurses. Project Advisors were accountable for getting targeted staff trained and having them sign an e-Confirmation and Commitment Pledge, an online form in which they attested that they recognized the importance of health literacy and would use health literacy skills. To assess whether staff were actually using teach-back and Ask Me 3, small teams chose surveyors to make rounds to observe behavior. Senior leadership, including the Chief Nursing Executive, the CMO, Facility Presidents, and Executive Vice Presidents reviewed the four TeachWell metrics collected monthly at the beginning of implementation, and quarterly for the remainder of the implementation period. Graphs of metrics were also shared with staff to provide feedback. The TeachWell Steering Committee disbanded after the end of the implementation period.

Health literacy at CHS was given another huge boost when one of its senior vice presidents was asked to take on a new role and became CHS’s first Senior Vice President of Patient Experience (CXO) overseeing a Patient Experience Team of 140. Among her first tasks was investigating how health literate CHS was. She and her team analyzed data from patient surveys and 197 responses to the Health Literacy Environmental Review that had been sent to all CHS facilities and practices. They determined that there was not a consistent “CHS way” for delivering health care. In response, CHS developed “the One Culture,” which asserted that CHS “will achieve its vision through the development of a single unified enterprise focused on developing enduring relationships with our patients based on superior personalized service and high quality outcomes.”

The Patient Experience Team now integrates health literacy throughout CHS. For example, a team member sits on each Differentiable Patient Experience Action Council, which the CXO established at each facility. These Councils, consisting of the Senior Vice President and other facility leadership – including those responsible for quality, safety, accreditation, education, and human resources – are a direct line into CHS’ daily operations. Patient Experience Team members have additional opportunities to infuse patient experience principles, including health literacy, throughout the system. For example, they are members of various Quality and Safety Operations Councils (QSOCs). While the entire team carries the banner for health literacy, CHS has only a single full-time staff member who works exclusively on health literacy and there is no budget earmarked for health literacy. This Health Literacy Consultant serves as an internal adviser, following up with staff members who were trained in plain language, and overseeing the operations of the Patient and Family Health Education Governance Council.

Given that the watch words of the Patient Experience Team are “include, inform, and inspire,” it is not surprising that health literacy was seen as central to delivering the type of experience that CHS wants to create. Toward that end, the CXO began by working with the Director of CHS’ Center for Advancing Pediatric Excellence, a longtime health literacy champion who had been co-chair of the HLTF and led the Health Literacy Learning Collaborative, and the Senior Vice-President for Marketing. Using a key driver diagram that showed how becoming health literate would result in better outcomes, patient satisfaction, and value, the CXO and colleagues convinced the CHS Board of Directors to formally adopt a goal of becoming health literate by 2020 and include it in the 2014 CHS system-wide strategic roadmap. Since then, CHS has annually assessed progress towards this goal using the 10 attributes of health literate health care organizations and reported all health literacy accomplishments to the Board. Health literacy has become an organization-wide expectation. Table 3 provides examples that CHS has taken to address each of the 10 attributes of a health literate organization.

Table 3.

Examples of Carolinas Healthcare System activities on 10 attributes of a health literate organization

| Attribute | Examples of Activities |

|---|---|

| 1. Leadership promotes |

|

| 2. Plans, evaluates and improves |

|

| 3. Prepares workforce |

|

| 4. Includes populations served |

|

| 5. Meets needs of all |

|

| 6. Communicates effectively |

|

| 7. Provides easy access |

|

| 8. Designs easy-to-use materials |

|

| 9. Addresses high-risk situations |

|

| 10. Explains coverage and costs |

|

CHS is an example of how leadership from the very top of an organization can drive the organization to become health literate. It also shows how fragile health literacy initiatives are: at the end of the Health Literacy Learning Collaborative and the first round of TeachWell, health literacy strategies did not get spread and health literacy activity died down. Fortunately, new committed leaders emerged and health literacy resurged as CHS concentrated on improving the patient experience. Health literacy has become infused throughout the system to the extent that it would not go away if any single individual were to leave the organization. It is not so deep-seated, however, that it does not require tending and expanding. CHS has pioneered health literacy measurement in the form of reporting on observed health literacy practices, but has only enforced it while scaling up initiatives. CHS acknowledges that the measures it has used are far from perfect, and like other systems continues to search for more and better gauges of health literate behavior. This, and the fact that CHS uses the ten attributes framework to report its health literacy progress annually to leadership, is a strong indication that CHS will continue its journey to become a health literate organization.

7.2. Intermountain Healthcare: Pursuing Health Literacy as a Prerequisite to Patient Engagement

Intermountain Healthcare is a Utah-based, not-for-profit system of 22 hospitals, 185 clinics, a Medical Group with some 1,400 employed physicians, a health plan division called SelectHealth, and other health services. In the wake of the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, Intermountain adopted a model of shared accountability, whereby patients are encouraged to take advantage of prevention and wellness programs, self-manage their conditions, and get more involved in decisions about their care. Three strategies were chosen as being instrumental to achieving shared accountability:

Redesigning care to ensure the delivery of evidence-based medicine.

Engaging patients in their health and care choices.

Aligning financial incentives for everyone who has a stake in healthcare.

A Patient Engagement Steering Committee (PESC) was formed to define the scope of patient engagement work at Intermountain. Initially, this committee was comprised of 25 representatives from around the system, led by Director of Clinical and Patient Engagement.

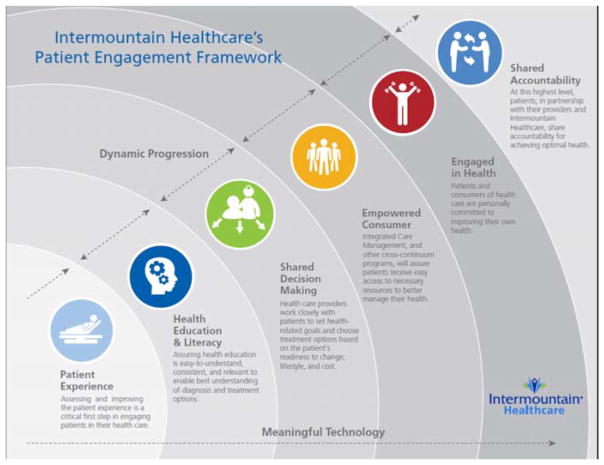

Over the course of a year of intense work, the PESC reviewed the research literature, conducted a SWOT analysis, and interviewed dozens of leaders within the organization as well as hundreds of patients. The PESC came to recognize the importance of health literacy as instrumental to engaging patients so that they could contribute to their health. The result was a Patient Engagement Framework, which included health education and health literacy as a foundational component. (See Figure 1.) The Framework was approved by Intermountain’s highest level leaders, the Operations Council.

Figure 1.

Intermountain Healthcare’s Patient Engagement Framework

Reprinted with permission from Intermountain Healthcare

To move from concept to reality, the Operations Council directed that the PESC be restructured to reduce the number of members and include key senior officials and operations leaders. Two councils, reporting directly to the PESC, were convened to implement the Framework: the Patient Experience Guidance Council and the Health Education and Health Literacy Effectiveness Guidance Council (HEHLE). Although the work of both councils could be included in an expansive definition of health literacy, at Intermountain it is the work of the HEHLE that is labeled as health literacy.

HEHLE members include staff at the Assistant Vice President level throughout the system, as well as staff responsible for patient and provider publications, clinical education, communications, nursing, physicians, and employee health. The HEHLE’s purpose is to develop, select, and deliver consistent, engaging, and effective education for clinical staff, providers, patients, families, communities and employees across the care continuum. HEHLE members constantly scanned the horizons, using outside resources to increase health literacy knowledge.

The HEHLE chose to use the “Ten Attributes of a Health Literate Health Care Organization” to gauge health literacy at Intermountain. It selected Intermountain’s “go-to” medical writer to undertake an informal health literacy gaps analysis on all aspects of the health system, from pharmacy to patient safety. The result was a report on what Intermountain was doing on each attribute, and what it needed to be doing. (See Table 4.) The assessment uncovered many pockets of health literacy activity, but found that they were not coordinated. It also found that some patient experience initiatives have significant health literacy overtones, such as Intermountain’s “healing commitments,”4 bedside reporting, patient communication boards (white boards in patients’ rooms), and narrating care as it is delivered.

Table 4.

Intermountain Healthcare assessment of health literacy activities and opportunities using 10 attributes of a health literate organization

| Attribute | Existing Activities | Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Leadership promotes |

|

|

| 2. Plans, evaluates and improves |

|

|

| 3. Prepares workforce |

|

|

| 4. Includes populations served |

|

|

| 5. Meets needs of all |

|

|

| 6. Communicates effectively |

|

|

| 7. Provides easy access |

|

|

| 8. Designs easy-to-use materials |

|

|

| 9. Addresses high-risk situations |

|

|

| 10. Explains coverage and costs |

|

|

Reprinted with permission from Intermountain Healthcare

The HEHLE decided it needed someone dedicated to promoting health literacy at Intermountain. The medical editor was chosen to be Intermountain’s Health Literacy Coordinator, its only employee who works on health literacy fulltime. Her position description holds her responsible for: ensuring health information for patients and consumers is easy to access, understand, and use; ensuring system-wide processes take health literacy into account; promoting system-wide health literacy standards; and developing a system-wide strategic plan for health literacy.

While the strategic plan was being developed, the HEHLE decided to act on some of the identified opportunities for improvement and score some “quick wins” to raise awareness of health literacy system-wide. One of these was the development a health literacy infographic and other health literacy content that could be dropped into presentations.

Another “quick win” was the development of an eLearning module to make health literacy more concrete to employees. Earlier Intermountain had created a training module for hospital nurses based on the teach-back tool in the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. The module was revised to include an introduction to health literacy and broadened to be applicable to all non-physician employees who interact with patients. Almost all of the approximately 25,000 employees across the system who were assigned to complete the module did so. Knowing that more than a one-time training is needed for staff to adopt teach-back and use it consistently, Intermountain created teach-back flash cards with conversational prompts to re-enforce the training. Subsequent communications workshops have focused on integrating teach-back into the daily workflow for specific clinical groups, including system-wide dietitians, diabetes educators, and newly hired physicians.

The HEHLE prioritized making education materials consistent across audiences (i.e., patient, provider, employee, community) while the strategic plan was being produced. Aligning patient education materials with treatment protocols ensured that patients got consistent information and instructions. The policy also served to provide clinicians with models of language to use with patients. For example, all clinician-facing materials were renamed from Hypertension to Blood Pressure in order to promote the use of plain language. Materials are scheduled to be reviewed every two years.

To ensure that all requests for new patient education materials were channeled through the Strategic Patient Education Team (SPET), a policy was set that materials not reviewed by the SPET could not be included in the EHR. The SPET assesses each new piece (using the PEMAT and other tools), vets the content with the appropriate clinical teams, and assures alignment with any related material. Because of dissatisfaction with vendor materials, Intermountain has increasingly relied on internal staff to design and write patient education materials. The health literacy review for new materials includes, whenever possible, input from the PFAC, an advisory group specifically for patient education formed with members of an adult literacy class in the community.

In January 2016 the HEHLE Guidance Council and the Patient Engagement Steering Committee approved a 3-year Health Literacy Strategic Plan. Noting the work Intermountain has completed on each of the 10 attributes of a health literate organization, the plan lays out a set of strategic initiatives as well as metrics for assessing progress. Proposed timelines for actions were flexible so that health literacy initiatives could be integrated most naturally with other initiatives.

One way that Intermountain has pushed its health literacy agenda forward is by integrating health literacy into major system-wide initiatives. For example, health literacy content was inserted into Intermountain patient safety initiative Zero Harm. Three pilot sites worked on processes to integrate teach-back into the Zero Harm workflow. They integrated it into daily safety huddle and asked the clinics to set goals around teach-back. For example, front desk staff at one clinic asked patients four questions: Did your healthcare provider ask you to repeat back any of your instructions? Do you understand what you need to do for your health when you get home? Did somebody ask you to tell you what you heard, or to repeat back what you learned? Do you feel confident knowing what you’re supposed to do when you get home?

Integrating teach-back into Zero Harm was one strategy used to engage physicians. Clinicians were also exposed to health literacy more broadly through clinical education. For example, when clinicians were taught a new procedure at a Simulation Center, they were taught teach-back as part of the process of educating the patient about the procedure. Moreover, physicians applying to give a lecture to their peers are now asked whether patient education is relevant to their topic and how they will address patient understanding in their talks.

Intermountain has taken advantage of a regional infrastructure for quality improvement to further health literacy goals. Poor scores from patient experience surveys activate regional patient experience managers. When health literacy has been a factor, the Health Literacy Consultant has been brought in to share health literacy tools and provide coaching on how to implement them. Intermountain’s plan is to explore which health education and health literacy practices generate the highest scores and spread those practices.

At Intermountain, the push to become a health literate organization was neither decreed from above by leadership nor driven by grass roots advocates. Rather, it was the natural consequence of organizational adoption of a model of shared accountability that necessitated patient engagement for its success. Intermountain found numerous ways to build on its previous efforts to make information easier to understand and the system easier to navigate. The approval of a 3-year Health Literacy Strategic Plan marked an acceleration of its journey. It did not, however, free up substantial new resources to address health literacy. Health literacy champions have worked to integrate health literacy into standard operating procedures. However, if enthusiasm for health literacy ebbs, it is possible that insufficiently ingrained health literate practices will fall into disuse.

7.3. Northwell Health: Linking Health Literacy to Diversity and Inclusion

Northwell Health, a health care network (formerly North Shore-LIJ Health System) has taken a different path toward becoming a health literate organization. Because Northwell has documented its own health literacy journey [82], this section only highlights some of ways Northwell’s trajectory is distinct from the other two systems described in this chapter.

The ascendency of health literacy at Northwell was largely due to the advocacy of a nurse turned educator. Her passion for improving patient education and other written materials, shared by a colleague who became Northwell Health’s Health Literacy and Patient Education Coordinator, raised health literacy’s profile, first on a regional basis and then at corporate level. Years of championing health literacy paid off when Northwell included health literacy in an office newly created to expand the delivery of culturally customized care in response to the growing diversity of the population served – the Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Health Literacy (ODIHL).