Abstract

Case

A 74‐year‐old woman with a week‐long history of cold symptoms was diagnosed with Lemierre syndrome that involved her left external jugular vein.

Outcome

The patient was successfully treated with 4 weeks of antibiotics and anticoagulant treatment. Typical cases of Lemierre syndrome involve only the internal jugular vein. The external jugular vein is anatomically distant from the pharyngolaryngeal space and usually does not receive blood or lymphatic flow from there. Thus, Lemierre syndrome ordinarily does not involve the external jugular vein and clinical characteristics of external jugular vein‐involving Lemierre syndrome have not been uncovered, mainly due to its rarity. Based on our review, it would not much differ from those of typical cases.

Conclusion

Considering the potential severity and mortality, more attention should be paid to this potentially fatal disease that may demonstrate atypical manifestation, as shown in this case. Accumulation of cases would be needed for further understanding.

Keywords: External jugular vein (EJV), Fusobacterium, jugular vein suppurative thrombophlebitis, Lemierre syndrome, septic pulmonary emboli (SPE)

Introduction

Lemierre syndrome has been classically defined as a disease caused by an acute anaerobic oropharyngeal infection with secondary thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein (IJV). As a result of the frequent use of antibiotics, the incidence rate of the disease has been reported to be in decline (estimated at approximately 1 per million per year),1 and Lemierre syndrome was recently described as a “forgotten disease”. However, it still remains as a potentially life‐threatening disease that deserves attention.2

The disease is originally a thrombophlebitis of the IJV, and cases involving the external jugular vein (EJV) have rarely been described. Only a few cases have been reported as far as we aware, and the clinical characteristics of such a condition remain to be elucidated. Here, we describe a case of EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome that occurred in an immunocompromised elderly patient, as well as a review of previously published reports.

Case Report

A 74‐year‐old woman with a past history of rheumatoid arthritis and type 2 diabetes mellitus was transferred to an emergency center because of high fever and respiratory distress, with a week‐long history of cold symptoms including pharyngeal pain. She had been prescribed prednisolone at 6 mg/day and methotrexate at 6 mg/week for rheumatoid arthritis. On arrival, she was conscious but her vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 96/48 mm Hg; heart rate, 145 b.p.m.; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/min; oxygen saturation, 90% on room air; and body temperature, 39.2°C. She complained of left temporal headache, but local inflammatory changes were absent. A whole‐body physical examination did not reveal any remarkable findings, except slightly swollen cervical lymph nodes. Laboratory examination results indicated high inflammation, severe pancytopenia, hypercoagulability, metabolic acidosis, renal insufficiency, and abnormal glucose tolerance (Table 1). Results of the laboratory examination fulfilled disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) diagnostic criteria defined by the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (7 points). Non‐enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) revealed peripheral nodules bilaterally (Fig. 1). Under the diagnosis of septic pulmonary emboli (SPE) and DIC with unknown apparent origin, the patient was admitted to our hospital.

Table 1.

Laboratory testing on admission of a 74‐year‐old woman with a week‐long history of cold symptoms

| White blood cells | 900/mm3 | LDH | 226 IU/L | Arterial blood gas (oxygen 5‐L mask) | |

| Neutrophils | 75.9% | AST | 29 IU/L | pH | 7.29 |

| Lymphocytes | 12.0% | ALT | 20 IU/L | PaCO2 | 20.8 mmHg |

| Monocytes | 1.0% | ALP | 767 IU/L | PaO2 | 166 mmHg |

| Eosinophils | 10.3% | T‐bil | 1.2 mg/dL | Lactate | 7.7 mmol/L |

| Basophils | 0.8% | BUN | 46.2 mg/dL | HCO3− | 12.7 mmol/L |

| Hemoglobin | 9.7 g/dL | Cre | 1.6 mg/dL | Base excess | −15.8 mmol/L |

| Platelets | 2 × 103/mm3 | TP | 4.6 g/dL | ||

| Alb | 1.7 g/dL | ||||

| PT‐INR | 1.16 | CRP | 24.8 mg/dL | ||

| APTT | 37.6 s | PCT | 85.07 ng/mL | ||

| Fibrinogen | 512 mg/dL | Na | 140 mEq/L | ||

| FDP | 64.3 μg/mL | K | 4.2 mEq/L | ||

| D‐dimer | 31.9 μg/mL | Cl | 110 mEq/L | ||

| TAT | 15.8 μg/L | Glu | 78 mg/dL | ||

| HbA1c | 7.1% | ||||

Alb, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cl, chloride; Cre, creatinine; CRP, C‐reactive protein; FDP, fibrinogen degradation products; Glu, glucose; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PCT, procalcitonin; PT‐INR, prothrombin time—international normalized ratio; TAT, thrombin–antithrombin III complex; T‐bil, total bilirubin; TP, total protein. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was examined according to the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program.

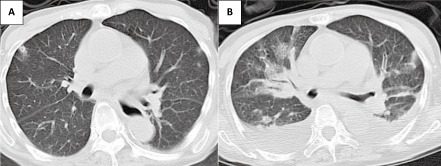

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography in a 74‐year‐old woman with a week‐long history of cold symptoms. Small peripheral nodules suggestive of septic emboli were seen bilaterally on admission (A), and massive pleural effusion emerged with the multiple emboli on day 2 (B).

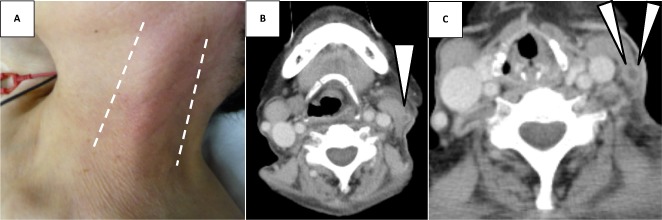

In intensive care unit (ICU), an empirical antimicrobial therapy of meropenem (1 g every 24 h), daptomycin (350 mg every 24 h) and micafungin (150 mg every 24 h) combined with leucovorin (6 mg every 6 h), hydrocortisone (100 mg every 8 h), granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor (75 μg every 24 h), i.v. immunoglobulin (5 g/day for 3 days), and platelet transfusion were immediately initiated. Approximately 6 h later, the left side of the patient's neck, along with the left sternocleidomastoid muscle, gradually became reddish (Fig. 2A). With the occurrence of high fever preceded with week‐long cold symptoms, embolization of the peripheral lung fields, and inflammatory findings at the cervical area, we strongly suspected Lemierre syndrome. Despite the absence of abnormal findings in the pharynx on physical examination, laryngoscopy successfully revealed inflammatory changes in the larynx, which strengthened our suspicion of Lemierre syndrome. Contrast‐enhanced CT carried out on day 2 successfully revealed a thrombus in the left EJV (Fig. 2B,C) with an exacerbation of SPE and pleural effusion (Fig. 1). No definitive findings concerning the abscess forming around the pharyngolarynx or abnormal inflammatory changes at the soft tissue around the neck were obtained. No intraoral lesions were found on examination by a dentist. Bacterial culture of the pharynx was negative for any pathogenic organisms. A transthoracic echocardiogram did not reveal any findings indicating infective endocarditis. Eventually, the patient was diagnosed with EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome secondary to laryngopharyngitis and i.v. heparin (15,000 IU daily) was added to the antibiotic therapy. On day 3, a Gram‐negative rod organism, which was later identified to be Fusobacterium nucleatum, was detected in anaerobic blood cultures and the antibiotics were de‐escalated to single doses of ampicillin/sulbactam (3 g every 8 h).

Figure 2.

Gross appearance and contrast‐enhanced computed tomography of the neck in a 74‐year‐old woman with a week‐long history of cold symptoms. Redness and swelling of her left neck along with sternocleidomastoid muscle appeared after admission (A). The thrombus formation and perivascular contrast enhancement, indicating thrombophlebitis, was seen inside the left external jugular vein (arrows) (B, upper slice; C, lower slice). The left internal jugular vein was totally intact and there was no abscess forming around the veins.

With these treatments, her systemic condition recovered promptly; the elevated serum inflammatory markers declined day by day and DIC tendency improved. After 1 week of intensive therapy, she was discharged from the ICU. Anticoagulant therapy was converted to warfarin when she left the ICU. Ampicillin/sulbactam was continued for 10 days but altered to a combination of ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 h) and clindamycin (600 mg every 8 h) because of drug‐induced nephritis. The subsequent clinical course was uneventful without requiring thrombectomy. A total of 4 weeks of i.v. antimicrobial therapy successfully resolved the thrombus in the left EJV, and the patient was discharged without any complications.

Discussion

To our knowledge, only three cases of Lemierre syndrome involving the EJV have been reported (Table 2). Schwartz et al.3 reported a case of a previously healthy 49‐year‐old man who developed right EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome after his upper right anterior gingiva was damaged while he was vigorously flossing his teeth 5 days prior. Shibasaki et al.4 reported a case of a 59‐year‐old man who presented with a week‐long history of fever and subsequent dentoalveolitis, and later developed left EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome. Lastly, Abe et al.5 described a case of a 30‐year‐old man with a preceding history of fever, throat pain, left facial pain, and lockjaw who developed left EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome.

Table 2.

Summary of published cases of Lemierre syndrome involving external jugular vein

| Case (Ref) | Age, years/sex | Location | Underlying disease | Preceding symptoms (duration) | Symptoms on admission | Pathogen | Complications | Anticoagulation (maintenance therapy) | Thrombectomy | Treatment period, weeks | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 49/M | Right | None | Damaged gingiva while flossing teeth (5 days) | Erythema over the right cheek and in the right submandibular region | Klebsiella pneumoniae | SPE, pleural effusions | Carried out but not described precisely | Carried out | 5 | Cured |

| 24 | 59/M | Left | None | Temporal pain, right maxillary abscess (1 week) | Temporal and tooth pain | Unknown | SPE, brain abscess, CI, facial nerve palsy, hearing loss | Heparin 12,000 IU daily (not described) | None | 9 | Cured |

| 35 | 30/M | Left | None | Cold symptoms, lockjaw, facial pain (1 week) | Respiratory discomfort | Unknown | SPE, DIC | Heparin 15,000 IU daily (not described) | Carried out | 4 | Cured |

| Present case | 74/F | Left | RA, DM, PSL, MTX | Cold symptoms (1 week) | Fever and respiratory discomfort | Fusobacterium nucleatum | SPE, pleural effusions | Heparin 15,000 IU daily (warfarin) | None | 4 | Cured |

CI, cerebral infarction; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy; DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; F, female; M, male; MTX, methotrexate; PSL, prednisolone; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SPE, septic pulmonary emboli.

In typical cases of Lemierre syndrome, the intervals between the preceding symptoms and the onset are usually within 1 week and patients are frequently complicated with SPE. Based on our summary (Table 2), the clinical features of EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome appear to be similar in these points. In contrast, the ages of the patients with EJV‐involving cases were relatively older (30–74 years), compared to typical IJV–involving Lemierre syndrome.6 The pathogen in the present case was a common organism of Lemierre syndrome, F. nucleatum,7 whereas one of the previous cases had Klebsiella pneumoniae and the other two had unknown pathogens. The three previously reported cases and the presented case of EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome were treated completely with long‐term antimicrobial therapy combined with anticoagulation therapy. Of note, the temporal headache which our patient and the patient in Case 2 complained of could be a specific symptom of EJV‐involving cases, even though the other two reports did not refer to the symptom. Anatomical differences between the IJV and EJV would explain this fact; EJV, but not IJV, runs through the temporal region.

Involvement of the EJV is anatomically unexpected. Pharyngeal infection usually progresses from the oropharynx to the parapharyngeal space by direct invasion or through the hematogenic or lymphatic pathways. The carotid sheath that encloses the IJV is located close to the parapharyngeal space, and the EJV is separately located over these tissues. Thus, direct invasion of pharyngeal infection of the EJV without involvement of surrounding tissues, including the IJV, scarcely occurs. Additionally, venous returns from the oropharynx space usually drain into the IJV, and therefore, EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome does not occur unless there is anomalous vascular connection from the oropharyngeal space to the EJV.3 A branch of the facial vein connects to both the IJV and EJV inside the parotid glands, and the retrograde bloodstream may deliver the inflammation inside the oropharynx space to the EJV.8

It was possible that the pathogenic organism infected the patient percutaneously in this case. However, we consider that the inflammation had spread from the laryngopharynx because of the existence of laryngopharyngitis, the pathogen being indigenous bacteria of the oropharynx, and the absence of a traumatic history.

Early diagnosis is essential for a better prognosis. Typically, the disease should be suspected in patients with antecedent pharyngitis, SPE, and persistent fever despite antimicrobial therapy. Local tenderness, swelling, and induration over the angle of the jaw or along the sternocleidomastoid muscle may be useful indicators of the disease.9 However, in our case, these conventional symptoms were absent on arrival at the hospital. Different from conventional cases that involve the IJV, the inflammatory cutaneous changes are assumed to be more distinct in our patient because the EJV is located near the skin surface. Neutropenia, probably due to methotrexate, was considered to be responsible for the absence of inflammatory cutaneous changes in our case.

Considering bacterial etiology, β‐lactams combined with β‐lactamase inhibitor or carbapenems would be recommended empirically. The duration of antimicrobial therapy has been reported to be at least 4 weeks.10 Resolution of venous thrombosis and pulmonary abscess should be followed up, if possible. For patients with ongoing sepsis and uncontrollable pulmonary emboli, excision of venous thrombosis would be considered; however, the validity of such surgical intervention is not warranted. Although a need of anticoagulant therapy in both therapeutic and preventive manners for Lemierre syndrome remains controversial,11 based on the review of published reports and our clinical experience, we consider use of anticoagulant therapy in the absence of contraindications would be justified.

In summary, we reported a case of EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome. Typical Lemierre syndrome usually involves the IJV, and the EJV is rarely invaded. Our review revealed that the clinical characteristics of EJV‐involving Lemierre syndrome would not much differ from those of typical cases and the prognosis would be fine. However, the number of cases was very small and accumulation of such conditions would be required for further understanding. Considering the potential severity and mortality, we may need to pay more attention to this fatal disease that sometimes demonstrates an atypical manifestation, as described in this case.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1. Hagelskjaer LH, Prag J, Malczynski J, Kristensen JH. Incidence and clinical epidemiology of necrobacillosis, including Lemierre's syndrome, in Denmark 1990–95. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1998; 17: 561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stokroos RJ, Manni JJ, de Kruijk JR, Soudijn ER. Lemierre syndrome and acute mastoiditis. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1999; 125: 589–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schwartz HC, Nguyen DC. Postanginal septicaemia with external jugular venous thrombosis: case report. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1999; 37: 144–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shibasaki Warabi Y, Yoshikawa H, Idezuka J, Yamazaki M, Onishi Y. Cerebral infarctions and brain abscess due to Lemierre syndrome. Intern. Med. 2005; 44: 653–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abe H, Kisara A, Yagishita Y. A case of Lemierre syndrome. ICU & CCU. 1998; 22: 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baker CC, Petersen SR, Sheldon GF. Septic phlebitis: a neglected disease. Am. J. Surg. 1979; 138: 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Riordan T, Wilson M. Lemierre's syndrome: more than a historical curiosa. Postgrad. Med. J. 2004; 80: 328–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaida MA, Niculescu V, Motoc A, Bolintineanu S, Sargan I, Niculescu MC. Correlations between anomalies of jugular veins and areas of vascular drainage of head and neck. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2006; 47: 287–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, Tamariz LJ. The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002; 81: 458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hagelskjaer Kristensen L, Prag J. Lemierre's syndrome and other disseminated Fusobacterium necrophorum infections in Denmark: a prospective epidemiological and clinical survey. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008; 27: 779–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Phua CK, Chadachan VM, Acharya R. Lemierre syndrome—should we anticoagulate? A case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Angiol. 2013; 22: 137–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]