Abstract

Case

A 77‐year‐old woman presented with neck swelling and odynophagia following a fall from standing height. She had no history of antiplatelet or anticoagulant use. Computed tomography of the chest showed an isodense to hypodense soft tissue mass in the bilateral carotid space, retropharyngeal space, and posterior mediastinum. With no airway obstruction symptoms, the patient was placed on bed rest under close observation.

Outcome

The mass decreased in size spontaneously over the 10 days following symptom onset, accompanied by overall clinical improvement. The patient was diagnosed with a posterior mediastinal hematoma.

Conclusion

This is the first reported case of posterior mediastinal hematoma caused by a neck hyperextension injury secondary to a simple fall in a patient with normal coagulation. The outcome was good; however, emergency physicians should be aware that hematomas necessitating airway management may occur after a fall.

Keywords: Accidental fall, cervical injury, elderly, hematoma, mediastinum

Introduction

Falls are a frequent reason for presentation to the emergency department. Posterior mediastinal hematoma (PMH) resulting from a simple fall is potentially fatal but rare, with only two cases previously reported.1, 2 We report a PMH in an individual with normal coagulation occurring after a neck hyperextension injury secondary to a fall from standing height (i.e., a simple fall).

Case

We report the case of a 77‐year‐old woman who lost her balance, fell into a U‐shaped gutter, and hit her forehead on a concrete wall, causing her neck to flex backwards. She remained conscious and was brought to a nearby medical clinic, where abrasions were found only on her forehead and left knee. While at the clinic, she began to experience swelling and discomfort in her neck and was taken to a local hospital.

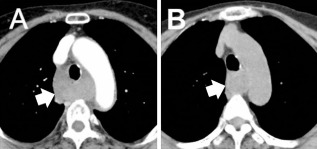

The patient's chief complaints on arrival at the hospital were neck swelling and odynophagia. She had a history of hypertension, for which she used two antihypertensive medications, but no history of antiplatelet or anticoagulant use. Glasgow Coma Scale score on arrival was E4V5M6, and saturation of peripheral oxygen was 99% in room air. The trachea and lungs were clear on auscultation, and no internal bleeding was suspected anywhere else. Blood coagulation parameters were within normal limits: prothrombin time was 10.3 s (105%, international normalized ratio 0.98), and activated partial thromboplastin time was 26.0 s. Hemoglobin level was 12.0 g/dL; white blood cell count, 12,500/μL; and platelet count, 175,000/μL. Contrast‐enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the head, neck, and chest showed an isodense to hypodense soft tissue mass in the bilateral carotid space, retropharyngeal space, and posterior mediastinum (Fig. 1A). The mass extended caudally to the level of the eighth thoracic vertebra and compressed the upper esophagus posteriorly (Fig. 1B). However, there was no significant tracheal narrowing or compression and no obvious lymph node enlargement or pleural effusion. The patient was transferred to our hospital for further evaluation and advanced care. She arrived at the emergency department approximately 4 h after the injury. A non‐contrast CT scan of the neck, chest, and abdomen was promptly carried out, on which the size and shape of the mass appeared unchanged from the previous scan. Observations strongly suggested a non‐bleeding hematoma extending from the retropharyngeal space to the posterior mediastinum.

Figure 1.

Contrast‐enhanced computed tomography scan of a 77‐year‐old woman with neck swelling and odynophagia following a fall from standing height. The scan shows a retropharyngeal/posterior mediastinal hematoma (white arrows), taken at the local hospital on the day of injury (A, sagittal; B, axial; aortic arch level).

The patient was admitted to the high‐care unit for observation. Contrast‐enhanced CT was carried out on the second day of hospitalization (Fig. 2A). There was no extravasation of contrast agent, suggesting no significant ongoing bleeding; the mass was not enhanced and had slightly decreased in size. The admission hemoglobin level of 12.0 g/dL decreased to 10.7 g/dL within 48 h. The patient was managed conservatively; she was observed in the high‐care unit for two days and then transferred to a general ward. The hematoma shrank spontaneously over the 10 days following symptom onset, and the neck swelling and odynophagia gradually improved. The patient was discharged home 11 days after admission. A follow‐up CT 18 days after symptom onset showed further shrinkage of the hematoma (Fig. 2B), accompanied by overall clinical improvement. Bronchoscopy, carried out on the ninth day of hospitalization, showed that the membranous portion of the infraglottic cavity was mildly swollen. Sparse submucosal hemorrhage of the airway wall was seen bilaterally from the level of the upper trachea to that of the segmental bronchus (Fig. 3A). Endobronchial ultrasound showed an abnormal heterogeneous echo area suspected of hosting the hematoma (Fig. 3B).

Figure 2.

(A) Contrast‐enhanced computed tomography scan of a 77‐year‐old woman with neck swelling and odynophagia following a fall from standing height, carried out at our hospital on day 2 after the injury. (B) Follow‐up non‐contrast computed tomography scan on day 18. On both images, the hematoma (white arrows) is reduced in size from the day of injury.

Figure 3.

Bronchoscopy (A) and endobronchial ultrasound (B) carried out on the ninth day of hospitalization of a 77‐year‐old woman with neck swelling and odynophagia following a fall from standing height. White arrows indicate submucosal hemorrhage of the airway wall (A) and the abnormal heterogeneous echo area suspected of hosting the hematoma (B).

Discussion

Falls are common reasons for emergency department visits. Although there is regional and international variation, a study in the UK found that three‐quarters of falls occurred in the elderly.3 Approximately 40% of blunt trauma injuries are related to a simple fall, and approximately 60% of such fall‐related injuries occur in the elderly. Compared with younger individuals, the elderly are more prone to damage to the head, chest, lower limbs, and pelvic area after a fall.4 Nevertheless, it is rare for PMH to follow a simple fall, with only two such cases previously reported, both in patients taking anticoagulants.1, 2 Other reported causes of PMH include injury to blood vessels, the esophagus, or the cervical vertebrae, as well as iatrogenesis and spontaneous hemorrhage.

Chest radiography may not show mediastinal widening clearly; therefore, CT is preferable for initial examination. Transesophageal echocardiography is 75% specific and 100% sensitive for PMH.5 On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the appearance of a hematoma changes with its age, with intensity increasing from hypointense or isointense to hyperintense on both T1‐ and T2‐weighted images.6 However, MRI is not routine for emergency patients at our hospital. We were unable to identify the mechanism by which the hematoma originated; if our patient had undergone MRI on arrival, we might have been able to do so. Therefore, we recommend that in patients with a PMH, MRI should be carried out to determine its origin.

Approximately 80% of elderly individuals injured by a simple fall are on anticoagulants at the time of injury.4 Posterior mediastinal hematoma rarely occurs in individuals with normal coagulation and no history of trauma. Up to 2013, only 47 cases of PMH had been reported in published works, the majority caused by high‐energy trauma such as our patient's neck hyperextension. Injury to ligamentous tissue and blood vessels around the anterior cervical spine can lead to the formation of a large retropharyngeal hematoma.7, 8 In addition, there have been previous reports of a retropharyngeal hematoma occurring simultaneously with a PMH.9, 10 Therefore, we strongly suspected that the hematoma in our case originated at the cervical level and spread downward.

In patients requiring intensive care, follow‐up imaging is necessary to determine the extent and activity of bleeding, and hemodynamic monitoring should be carried out. Airway obstruction and other complications, such as spinal canal injury or spinal epidural hematoma, are reportedly rare. Nevertheless, the airway should be managed carefully until the size of the hematoma stabilizes. In stable patients, conservative management can be used. If the hematoma does not shrink, invasive treatment should be considered. Our patient recovered well with only supportive care; despite the extent of the hematoma, the large vessels were not injured.

Our experience shows that PMH may occur even in patients who have suffered only a simple fall, have normal coagulation, and have not directly injured the chest. Emergency physicians should be aware of this possibility and of the potential need for airway management in such patients.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1. Josse JM, Ameer A, Alzaid S et al Posterior mediastinal hematoma after a fall from standing height: A case report. Case Rep. Surg. 2012; 2012: 672370. 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pasumarthy L. Posterior mediastinal hematoma—a rare case following a fall from standing height: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2007; 1: 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scuffham P, Chaplin S, Legood R. Incidence and costs of unintentional falls in older people in the United Kingdom. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003; 57: 740–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bergeron E, Clement J, Lavoie A et al A simple fall in the elderly: Not so simple. J. Trauma 2006; 60: 268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Le Bret F, Ruel P, Rosier H, Goarin JP, Riou B, Viars P. Diagnosis of traumatic mediastinal hematoma with transesophageal echocardiography. Chest 1994; 105: 373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seelos KC, Funari M, Chang JM, Higgins CB. Magnetic resonance imaging in acute and subacute mediastinal bleeding. Am. Heart J. 1992; 123: 1269–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Penning L. Prevertebral hematoma in cervical spine injury: Incidence and etiologic significance. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1981; 136: 553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morita S, Iizuka S, Hirakawa H, Higami S, Yamagiwa T, Inokuchi S. A 92‐year‐old man with retropharyngeal hematoma caused by an injury of the anterior longitudinal ligament. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2010; 13: 120–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iskander M, Siddique K, Kaul A. Spontaneous atraumatic mediastinal hemorrhage: Challenging management of a life‐threatening condition and literature review. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2013; 1: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Findlay JM, Belcher E, Black E, Sgromo B. Tracheo‐oesophageal compression due to massive spontaneous retropharyngeal haematoma. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2013; 17: 179–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]