Abstract

Early aggressive hemodynamic resuscitation using elevated plasma lactate as a marker is an essential component of managing critically ill patients. Therefore, measurement of blood lactate is recommended to stratify patients based on the need for fluid resuscitation and the risks of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and death. Hyperlactatemia is common among critically ill patients, and lactate levels and their trend may be reliable markers of illness severity and mortality. Although hyperlactatemia has been widely recognized as a marker of tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion, it can also result from increased or accelerated aerobic glycolysis during the stress response. Additionally, lactate may represent an important energy source for patients in critical condition. Despite its inherent complexity, the current simplified view of hyperlactatemia is that it reflects the presence of global tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion with anaerobic glycolysis. This review of hyperlactatemia in critically ill patients focuses on its pathophysiological aspects and recent clinical approaches. Hyperlactatemia in critically ill patients must be considered to be related to tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion. Therefore, appropriate hemodynamic resuscitation is required to correct the pathological condition immediately. However, hyperlactatemia can also result from aerobic glycolysis, unrelated to tissue dysoxia, which is unlikely to respond to increases in systemic oxygen delivery. Because hyperlactatemia may be simultaneously related to, and unrelated to, tissue hypoxia, physicians should recognize that resuscitation to normalize plasma lactate levels could be over‐resuscitation and may worsen the physiological status. Lactate is a reliable indicator of sepsis severity and a marker of resuscitation; however, it is an unreliable marker of tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion.

Keywords: Beta‐2 adrenergic receptor, gluconeogenesis, hypoperfusion, lactate, resuscitation

Introduction

Early aggressive hemodynamic resuscitation is recommended for managing critically ill patients, especially those with severe trauma and sepsis. Resuscitation is a critical component of management that is required beyond the identification of the origin of major hemorrhage and its control1 and identification of the septic focus and its treatment with appropriate antibiotics.2, 3

Elevated plasma lactate levels have been recommended as a parameter for hemodynamic resuscitation. In the management of patients with trauma, it has been suggested that up to 85% of severely injured patients continue to exhibit inadequate tissue oxygenation after normalization of the conventional markers of resuscitation, including restoration of normal blood pressure, heart rate, and urine output.4 Therefore, measurement of blood lactate is recommended to stratify patients based on the need for ongoing fluid resuscitation, the risk of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and death,4 as a marker for identifying patients requiring early aggressive resuscitation.5

Hyperlactatemia is common among patients requiring critical care, and lactate levels and their trend may be reliable markers of illness severity and mortality.6, 7 Lactate was recently included in a multibiomarker‐based outcome risk model for patients with septic shock.8 Although hyperlactatemia has been widely recognized as a marker of tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion, the source, biochemistry, and metabolic functions of lactate remain unclear. Recently, it was clearly suggested that hyperlactatemia could result not only from tissue hypoxia or anaerobic glycolysis but also from increased or accelerated aerobic glycolysis during the stress response.9, 10, 11 Additionally, lactate may represent an important energy source for patients in critical condition.9, 11, 12 Despite its complexity, hyperlactatemia interpretation has been simplified as representing the presence of global tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion with anaerobic glycolysis.10, 13

Herein, we review the pathophysiological aspects and recent clinical approaches for hyperlactatemia in critically ill patients.

Lactate Production and Removal

Production and removal of lactate from blood

The daily lactate production in resting humans is estimated as 20 mmol/kg,14 primarily from highly glycolytic tissues such as skeletal muscles.15 The reaction for generating or consuming lactate is shown below:

Pyruvate + NADH + H+ ⇌ lactate + NAD+.

Pyruvate is generated largely by anaerobic glycolysis. The redox‐coupled interconversion of pyruvate and lactate occurs in the cytosol and is catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase. The blood lactate : pyruvate ratio is maintained at approximately 10:1; therefore, any condition that increases pyruvate generation will increase lactate generation (Fig. 1).

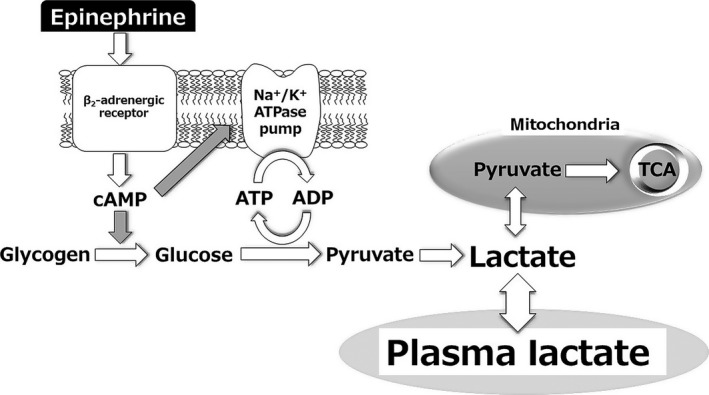

Figure 1.

Epinephrine‐induced lactate production. Epinephrine increases cyclic AMP (cAMP) production through β2‐adrenergic receptor activation, glycogenolysis/glycolysis stimulation, and Na+/K+‐ATPase pump activation, which converts adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to adenosine diphosphate (ADP). ADP reactivates glycolysis and generates pyruvate through a cAMP‐dependent mechanism. These combined mechanisms result in lactate production. AMP, adenosine monophosphate; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Lactate can be metabolized by the liver and the kidneys either through direct oxidation or as a source of glucose,9, 11 and the liver accounts for up to 70% of whole body lactate clearance.16 Under normal conditions, the generation and consumption of lactate are equivalent, which results in a stable concentration of lactate in the blood.17

Gluconeogenesis and oxidation as major mechanisms of lactate metabolism

Lactate is reconverted to pyruvate and metabolized in the liver, kidney, and other tissues through the Cori cycle, which generates glucose and consumes adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (gluconeogenesis).12 Lactate is also metabolized through the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation in the liver, kidney, muscle, heart, brain, and other tissues, generating ATP when pyruvate is oxidized to carbon dioxide and water.

Half of lactate is metabolized through oxidation at rest, and 75–80% during exercise.18 In contrast, lactate production by muscle and other tissues is coupled with its conversion to glucose (gluconeogenesis).19 Thus, lactate is an important precursor of gluconeogenesis and a key source of glucose.20

Under stress conditions, lactate has been suggested to act as a biofuel that eliminates blood glucose use and provides additional glucose.12 Therefore, hyperlactatemia may indicate a protective response to stress under critical conditions.

Another Pathway of Lactate Production and Hyperlactatemia

In tissue hypoxia, lactate is overproduced and underutilized because of impaired mitochondrial oxidation,17 largely through anaerobic glycolysis.9, 11 However, hyperlactatemia can also result from aerobic glycolysis, independent of tissue hypoxia.11 Under stress conditions, aerobic glycolysis is an important mechanism for rapid ATP generation. In the hyperdynamic stage of sepsis, epinephrine‐dependent stimulation of the β2‐adrenoceptor augments glycolytic flux both directly and through enhancement of sarcolemmal Na+/K+‐ATPase.21 Other conditions associated with elevated epinephrine levels, such as severe trauma and cardiogenic shock, can cause hyperlactatemia through this mechanism. In inflammatory states, aerobic glycolysis can also be driven by cytokine‐dependent stimulation of cellular glucose uptake.22

During high‐intensity exercise and shivering, hyperlactatemia is frequently observed. However, oxygen saturation of myoglobin was found to remain stable at high exercise intensity and correlate poorly with circulating lactate concentration.23 Several studies have shown significant correlation between plasma lactate concentrations and epinephrine levels.23, 24 Based on these findings, hyperlactatemia during exercise may reflect increased aerobic glycolysis stimulated by epinephrine rather than anaerobic glycolysis due to tissue hypoxia.

The role of Na+/K+‐ATPase pump stimulation was evaluated in skeletal muscle of patients with septic shock and shown to be a leading source of lactate formation through aerobic glycolysis.25 Recently, long‐term β‐blocker therapy was shown to decrease the blood lactate concentration of patients with severe sepsis at presentation.26 The use of blood lactate measurement as a triage tool in the initial assessment of septic patients undergoing β‐blocker therapy may therefore underestimate the severity of the condition.

Although other mechanisms have been suggested,9 aerobic glycolysis and tissue hypoxia appear to be the key factors in hyperlactatemia. Notably, the two are not mutually exclusive and can simultaneously contribute to hyperlactatemia (Fig. 1).

Lactate and its Clearance are Useful Prognostic Markers

The mechanism of hyperlactatemia in critical illness is multifactorial and associated with factors beyond tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion.27, 28 Lactic acidosis refractory to standard resuscitation is frequently caused by increased aerobic glycolysis in skeletal muscle instead of anaerobic glycolysis from hypoperfusion. Continued resuscitation attempts targeting lactate levels may thus lead to unnecessary blood transfusion and use of inotropic agents.27 It was also suggested that resuscitation efforts to normalize lactate for hyperlactatemia in the later phase of sepsis could be flawed and potentially harmful.10 However, the data supporting the clinical utility of lactate as a marker of early sepsis recovery are robust. In a recently revised sepsis definition, serum lactate level >2 mmol/L (18 mg/dL) has been used as a marker of circulatory and cellular/metabolic abnormalities to define septic shock, enough to substantially increase mortality.29 In critical illness‐related stress conditions, elevated lactate level is also an independent predictor of mortality.30, 31

The 2008 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines recommended measurement of lactate at initial presentation, with an elevated value signifying tissue hypoperfusion and necessitating resuscitation.32 Although they suggested measuring lactate only at the time of presentation, serial evaluation, including lactate clearance, may have greater value, as suggested in the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines 2012.2

Although presence of hyperlactatemia can be a marker of tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion complicated with cellular/metabolic abnormalities,29 lactate clearance has been suggested as a parameter to evaluate the effectiveness of resuscitation. The clinical relevance of lactate and its clearance have been repetitively evaluated. Lactate clearance greater than 10% from the initial value is predictive of survival from septic shock, and targeting 10% clearance provided similar survival rates to targeting central venous oxygen saturation. 33, 34 In patients with sepsis, lactate clearance greater than 20% during the initial 8 h showed a 22% decline in mortality risk relative to clearances less than 20%.5 Furthermore, early lactate normalization was a survival predictor in patients with severe sepsis.35 A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials evaluating the effect of early lactate clearance‐guided therapy in patients with sepsis36 showed that lactate clearance‐guided therapy was associated with reduction in mortality. In another meta‐analysis, Zhang et al.37 found that the pooled relative risk for all‐cause mortality in critically ill patients was 0.38 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29–0.50). They concluded that lactate clearance was predictive of a lower mortality rate.

The clinical significance of lactate monitoring was also evaluated. Jansen and colleagues prospectively assessed the effect of lactate monitoring and resuscitation directed at decreasing lactate levels in intensive care unit (ICU) patients admitted with lactate levels ≥ 3.0 mEq/L.5 Treatment was targeted at decreasing lactate levels by ≥ 20% every 2 h for the initial 8 h. Hospital mortality was lower and organ failures improved significantly with lactate monitoring.

Patients with Severe Hyperlactatemia may Comprise a Heterogeneous Population

In critically ill patients, severe hyperlactatemia is not a rare condition. Recently, Haas and colleagues retrospectively analyzed patients with plasma lactate levels ≥10 mmol/L.38 Although the overall mortality among ICU patients was 9.8%, that of patients with severe hyperlactatemia was 78.2%. Thus, hyperlactatemia was associated with death in the ICU (odds ratio, 1.35 [95% CI, 1.23–1.49; P < 0.001]). The main etiology for severe hyperlactatemia was sepsis (34.0%), cardiogenic shock (19.3%), and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (13.8%). Patients developing severe hyperlactatemia after >24 h of ICU treatment had significantly higher mortality (89.1%) than patients developing severe hyperlactatemia within 24 h of ICU admittance (69.9%, P < 0.0001). Lactate clearance after 12 h showed a receiver–operating characteristic area under the curve value of 0.91 for predicting ICU mortality (cut‐off yielding highest sensitivity and specificity, 12‐h lactate clearance of 32.8%). In patients with 12‐h lactate clearance <32.8%, ICU mortality was 96.6%. Severe hyperlactatemia is thus associated with extremely high ICU mortality, especially when there is no marked lactate clearance within 12 h.

However, patients with severe hyperlactatemia may comprise heterogeneous etiologies. Intensive care unit mortality, peak lactate concentration, and 12‐h clearance were evaluated in etiological subgroups. The respective ICU mortality and 12‐h lactate clearance (95% CI) for each subgroup are as follows: sepsis, 90.4% and −3.3% (−29.7 to 34.9%); cardiogenic shock, 0.5% and −2.7% (−28.9 to 39.6%); postoperative cardiosurgical patients, 3.8% and 73.8% (45.4 to 81.3%); cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 8.2% and 4.1% (−13.0 to 64.8%); hemorrhagic shock, 70.0% and 25.8% (−6.3 to 74.9%); liver failure, 84.6% and 1.5% (−21.9 to 26.2%); mesenteric ischemia, 100.0% and −18.9% (−54.8 to 21.8%); and seizure, 0% and 89.7% (81.3 to 91.7%).

Although severe hyperlactatemia in critically ill patients is strongly associated with high ICU mortality, the etiology and clearance rates show heterogeneity.

Conclusions

Hyperlactatemia in critically ill patients must be considered to be related to tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion. Therefore, appropriate hemodynamic resuscitation is required to correct the pathological condition immediately. However, hyperlactatemia resulting from aerobic glycolysis unrelated to tissue dysoxia is unlikely to respond to increases in systemic oxygen delivery.

Because hyperlactatemia can be simultaneously related to, and unrelated to, tissue hypoxia, physicians should recognize that resuscitation to normalize plasma lactate levels could be over‐resuscitation and worsen the physiological status. Thus, lactate is a reliable indicator of sepsis severity and a marker of resuscitation, but is not a reliable marker of tissue hypoxia/hypoperfusion.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the fund of Tohoku Kyuikai and departmental fund of the Division of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine.

References

- 1. ATLS Subcommittee; American College of Surgeons' Committee on Trauma; International ATLS working group . Advanced trauma life support (ATLS®): the ninth edition. J. Trauma Acute. Care Surg. 2013;74:1363–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013; 39: 165–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jones AE, Brown MD, Trzeciak S et al The effect of a quantitative resuscitation strategy on mortality in patients with sepsis: a meta‐analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2008; 36: 2734–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tisherman SA, Barie P, Bokhari F et al Clinical practice guideline: endpoints of resuscitation. J. Trauma 2004; 57: 898–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Schoonderbeek FJ et al Early lactate‐guided therapy in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, open‐label, randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010; 182: 752–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cerovic O, Golubovic V, Spec‐Marn A, Kremzar B, Vidmar G. Relationship between injury severity and lactate levels in severely injured patients. Intensive Care Med. 2003; 29: 1300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nichol A, Bailey M, Egi M et al Dynamic lactate indices as predictors of outcome in critically ill patients. Crit. Care 2011; 15: R242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wong HR, Lindsell CJ, Pettila V et al A multibiomarker‐based outcome risk stratification model for adult septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2014; 42: 781–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garcia‐Alvarez M, Marik P, Bellomo R. Sepsis‐associated hyperlactatemia. Crit. Care 2014; 18: 503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garcia‐Alvarez M, Marik P, Bellomo R. Stress hyperlactataemia: present understanding and controversy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014; 2: 339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kraut JA, Madias NE. Lactic acidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014; 371: 2309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller BF, Fattor JA, Jacobs KA et al Lactate and glucose interactions during rest and exercise in men: effect of exogenous lactate infusion. J. Physiol. 2002; 544: 963–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mizock BA, Falk JL. Lactic acidosis in critical illness. Crit. Care Med. 1992; 20: 80–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Connor H, Woods HF. Quantitative aspects of L(+)‐lactate metabolism in human beings. Ciba Found. Symp. 1982; 87: 214–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doherty JR, Cleveland JL. Targeting lactate metabolism for cancer therapeutics. J. Clin. Invest. 2013; 123: 3685–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jeppesen JB, Mortensen C, Bendtsen F, Moller S. Lactate metabolism in chronic liver disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2013; 73: 293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Madias NE. Lactic acidosis. Kidney Int. 1986; 29: 752–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mazzeo RS, Brooks GA, Schoeller DA, Budinger TF. Disposal of blood [1‐13C]lactate in humans during rest and exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985; 1986(60): 232–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Consoli A, Nurjhan N, Reilly JJ Jr, Bier DM, Gerich JE. Contribution of liver and skeletal muscle to alanine and lactate metabolism in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1990; 259: E677–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kreisberg RA, Pennington LF, Boshell BR. Lactate turnover and gluconeogenesis in normal and obese humans. Effect of starvation. Diabetes 1970; 19: 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levy B, Desebbe O, Montemont C, Gibot S. Increased aerobic glycolysis through beta2 stimulation is a common mechanism involved in lactate formation during shock states. Shock 2008; 30: 417–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taylor DJ, Faragher EB, Evanson JM. Inflammatory cytokines stimulate glucose uptake and glycolysis but reduce glucose oxidation in human dermal fibroblasts in vitro . Circ. Shock 1992; 37: 105–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Richardson RS, Noyszewski EA, Leigh JS, Wagner PD. Lactate efflux from exercising human skeletal muscle: role of intracellular PO2. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985; 1998(85): 627–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hughson RL, Green HJ, Sharratt MT. Gas exchange, blood lactate, and plasma catecholamines during incremental exercise in hypoxia and normoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985; 1995(79): 1134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levy B, Gibot S, Franck P, Cravoisy A, Bollaert PE. Relation between muscle Na+K+ ATPase activity and raised lactate concentrations in septic shock: a prospective study. Lancet 2005; 365: 871–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Contenti J, Occelli C, Corraze H, Lemoel F, Levraut J. Long‐Term beta‐Blocker Therapy Decreases Blood Lactate Concentration in Severely Septic Patients. Crit. Care Med. 2015; 43: 2616–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. James JH, Luchette FA, McCarter FD, Fischer JE. Lactate is an unreliable indicator of tissue hypoxia in injury or sepsis. Lancet 1999; 354: 505–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levraut J, Ciebiera JP, Chave S et al Mild hyperlactatemia in stable septic patients is due to impaired lactate clearance rather than overproduction. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998; 157: 1021–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW et al The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis‐3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mikkelsen ME, Miltiades AN, Gaieski DF et al Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and shock. Crit. Care Med. 2009; 37: 1670–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nichol AD, Egi M, Pettila V et al Relative hyperlactatemia and hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a retrospective multi‐centre study. Crit. Care 2010; 14: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM et al Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit. Care Med. 2008; 36: 296–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S et al Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2010; 303: 739–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nguyen HB, Rivers EP, Knoblich BP et al Early lactate clearance is associated with improved outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2004; 32: 1637–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Puskarich MA, Trzeciak S, Shapiro NI et al Whole blood lactate kinetics in patients undergoing quantitative resuscitation for severe sepsis and septic shock. Chest 2013; 143: 1548–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gu WJ, Zhang Z, Bakker J. Early lactate clearance‐guided therapy in patients with sepsis: a meta‐analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Intensive Care Med. 2015; 41: 1862–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang Z, Xu X. Lactate clearance is a useful biomarker for the prediction of all‐cause mortality in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2014; 42: 2118–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haas SA, Lange T, Saugel B et al Severe hyperlactatemia, lactate clearance and mortality in unselected critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2016; 42: 202–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]