Abstract

Background: The lack of consensus on the best methodology for identifying cases of non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction (NTSCD) in administrative health data limits the ability to determine the burden of disease and provide evidence-informed services. Objective: The purpose of this study is to develop an algorithm for identifying cases of NTSCD with Canadian health administrative databases using a case-based approach. Method: Data were provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information that included all acute care hospital and day surgery (Discharge Abstract Database), ambulatory (National Ambulatory Care Reporting System), and inpatient rehabilitation records (National Rehabilitation Reporting System) of patients with neurological impairment (paraplegia, tetraplegia, and cauda equina syndrome) between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2011. The approach to identify cases of NTSCD involved using a combination of diagnostic codes for neurological impairment and NTSCD etiology. Results: Of the initial cohort of 23,703 patients with neurological impairment, we classified 6,362 as the “most likely NTSCD” group (had a most responsible diagnosis or pre-existing diagnosis of NTSCD and diagnosis of neurological impairment); 2,777 as “probable NTSCD” defined as having a secondary diagnosis of NTSCD, and 11,179 as “possible NTSCD” who had no NTSCD etiology diagnoses but neurological impairment codes. Conclusion: The proposed algorithm identifies an inpatient NTSCD cohort that is limited to patients with significant paralysis. This feasibility study is the first in a series of 3 that has the potential to inform future research initiatives to accurately determine the incidence and prevalence of NTSCD.

Keywords: classification, epidemiology, etiology, health administrative data, non-traumatic spinal cord injury, spinal cord diseases

Compared to traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI), there is much less research on non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction (NTSCD). The etiology of NTSCD is complex with a variety of underlying causes, and currently there is very little homogeneity in the literature.1,2 There are a variety of causes of NTSCD, including degenerative disc disease, spinal stenosis, tumors, vascular disease, and inflammatory conditions, with varying levels of associated neurological impairment and care pathways. Identifying a non-traumatic cohort is a difficult task that should consider cause, neurological impairment, and clinical points of care within the health care system. A number of studies have identified a need for improvement in the documentation and classification of NTSCD to enable more effective measurement of the burden of the disease.3–5

Currently there are no reliable estimates of incidence and prevalence of NTSCD.6,7 In some incidence studies, both chronic NTSCD (congenital and genetic cases) and new onset patients are included in the study sample; other studies have included multiple sclerosis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, which do not necessarily constitute NTSCD.5 Accurate estimates of incidence and prevalence are necessary to inform resource allocation for health care delivery and system performance monitoring. In Australia and Canada, the incidence of NTSCD has been estimated to be about one and a half times greater than for TSCI.8–10 A number of reports have applied incidence and prevalence rates from other countries to their own population in an attempt to estimate burden.6,7 Using rates from Australia and Canada, Noonan et al6 estimated the national incidence and prevalence of SCI. By applying TSCI and NTSCD discharge incidence rates to historical Canadian population demographics, prevalence of SCI in Canada was estimated to be 85,556 persons (51% TSCI and 49% NTSCD). Reducing assumptions and using more representative populations will allow for refined estimates.

Another limitation of current literature is that many studies in North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa have relied on data from single- or multicenter specialized rehabilitation units because NTSCD cases can be easily identified.1,3,10–23 Methodological differences make it difficult for direct comparisons between studies, as there are differences in inclusion criteria for case ascertainment, diagnosis accuracy, referral patterns, and study time periods. In addition, NTSCD patients managed in acute care or nonspecialist rehabilitation units are less likely to be reported to SCI registries and are often excluded from such studies.5 The implication of using data exclusively from a single clinical point of care is an underestimate of the true incidence of NTSCDs due to incomplete case ascertainment.

One way to overcome incomplete case ascertainment is to obtain a population-based sample using health administrative data that include the entire population at risk and multiple clinical points of care. There is only one published study that used health administrative data to identify episodes of acute NTSCD to estimate burden in Victoria, Australia. Within a single state, New et al extracted data on all patients age 15 years and older with a new diagnosis of NTSCD who were admitted to hospital or that occurred as a complication during inpatient stay between July 1, 2000 and June 30, 2006.4 They identified 631 patients for an average age-adjusted incidence rate of 26.3 cases per million per year. New and colleagues recommend replication, validation, and refinement of their methodology used to calculate the incidence of NTSCD.

This article is the first in a series of 3 in this issue describing the development, findings, and validation of an algorithm to identify patients with NTSCD in Canada using health administrative data. The objectives of this article are to describe the development of the approach and to discuss the strengths and limitations of using administrative data for identifying patients with NTSCD. The second article (“Validation of Algorithm to Identify Persons with Non-traumatic Spinal Cord Dysfunction in Canada Using Administrative Health Data”) describes the population characteristics of patients identified by the algorithm and compares and contrasts that to the literature, and the third article (“Characteristics of Non-traumatic Spinal Cord Dysfunction in Canada Using Administrative Health Data”) is a validation study of the algorithm using chart review data from a single center in Alberta, Canada as the gold standard. Taken together, these studies represent the first attempt to analyze NTSCD in administrative data at a national level.

Methods

Data sources

The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI; www.cihi.ca) facilitates data collection of standardized administrative health care databases, including the hospital Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), the National Ambulatory Care Resource System (NACRS), and the National Rehabilitation Reporting System (NRS). The DAD contains all hospital discharge records from across Canada (excluding Quebec) and includes diagnostic information under the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10-CA) codes. Up to 25 primary clinical diagnoses, comorbid conditions, and medical complications are recorded on a single abstract, which represents one discharge record. Each diagnosis code has a corresponding diagnosis type that can indicate reasons for admission, comorbidities present at admission, diagnoses for which a patient has undergone treatment, and complications that arise during the hospital stay. The NACRS contains hospital- and community-based emergency and ambulatory care visits. Each NACRS record includes up to 10 ICD-10-CA medical diagnoses and corresponding diagnosis types. The NRS includes client data collected from participating adult in-patient rehabilitation facilities and programs across Canada. Patients are assigned to 1 of 17 rehabilitation client groups upon admission based on clinical diagnosis, level of impairment, activity limitation, or participation restrictions. The spinal cord dysfunction rehabilitation client group classifies patients with paraplegia or tetraplegia due to non-traumatic causes.

Data sets

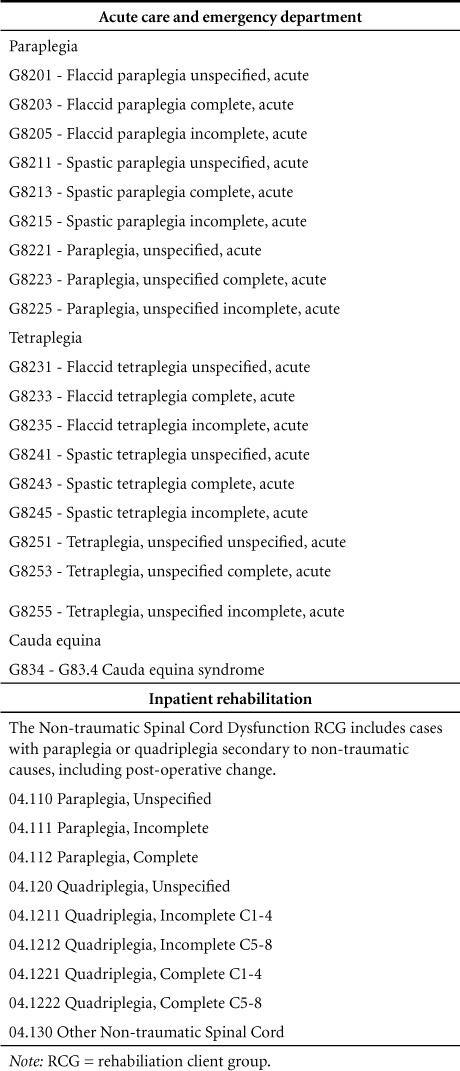

In 2011, CIHI approved a data request from the Rick Hansen Institute, which included acute care hospital, emergency department, and inpatient rehabilitation admission records extracted between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2011 from the DAD, NACRS, and NRS databases as a series of separate SAS formatted files for each fiscal year. The data included records of all patients with a diagnosis of paraplegia (ICD10-CA G82.2), tetraplegia (ICD10-CA G82.5), or cauda equina syndrome (ICD10-CA G83.4) recorded during an acute care hospital or emergency department visit or with a primary diagnosis of non-traumatic spinal cord injury during a rehabilitation stay (Rehab Client Group RCG 4.1) between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2011 in Canada (excluding Quebec) (see Table 1). Records for any DAD, NACRS, or NRS visits for any reason belonging to these patients between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2011 were also provided. All files included multiple records per patient. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at Toronto Rehabilitation Institute.

Table 1.

Neurological impairment codes

Exclusion criteria

From the DAD, duplicate cases defined as records with the same transaction number that is unique to every discharge abstract, missing unique patient identifier numbers that would prevent record linkage across datasets, and patients with a diagnosis of TSCI within the 7-year study period were excluded. The latter was excluded in order to ensure that paraplegia or tetraplegia was due to non-traumatic causes.

Characterizing NTSCD etiology using ICD-10-CA codes

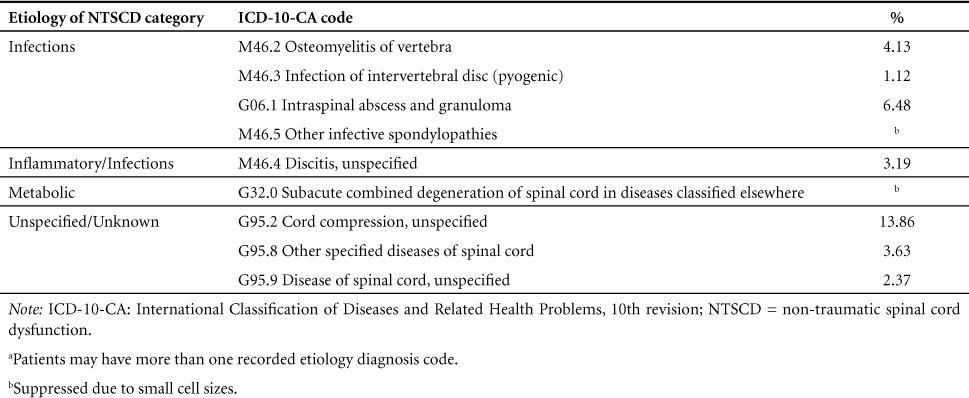

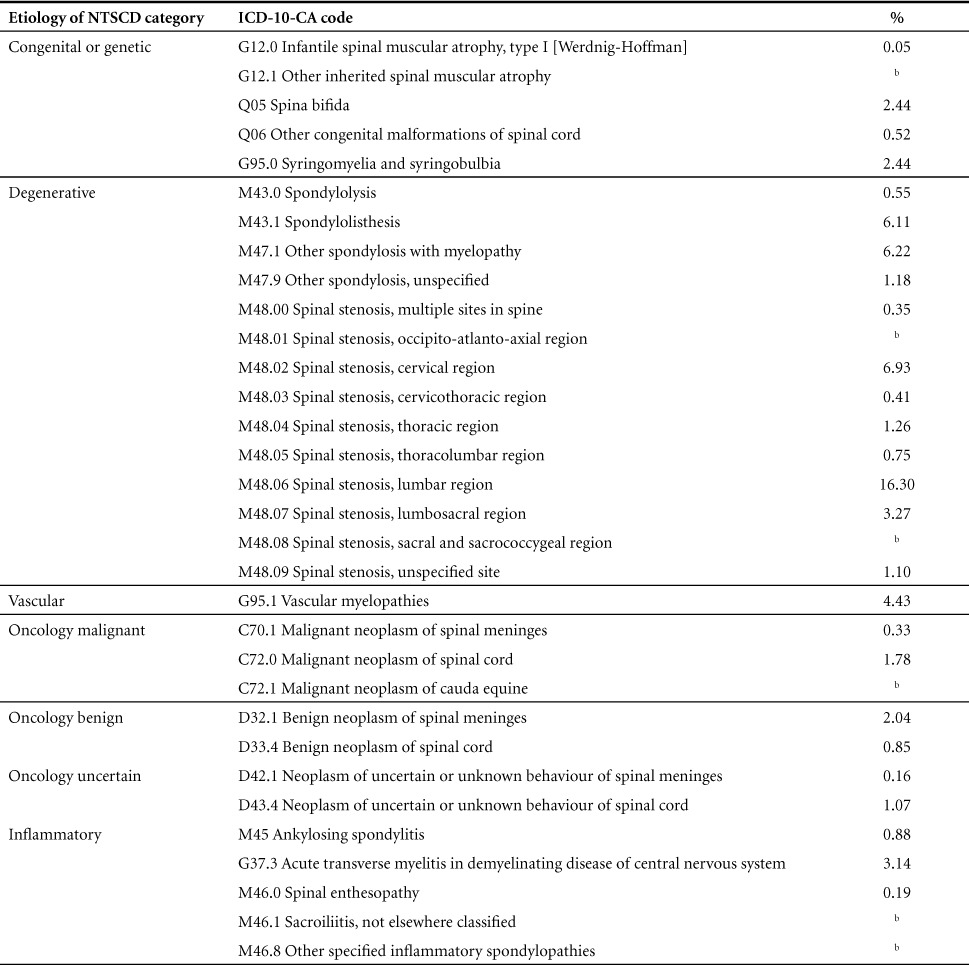

Based on the data extracted from the CIHI, every unique patient represented in the datasets should have had a diagnosis of paraplegia or tetraplegia during the 7-year study window. To determine the condition potentially causing the neurological impairment, NTSCD etiology was classified in accordance with the International Spinal Cord Injury Data Sets for NTSCI where possible, based on the descriptions of the ICD-10-CA diagnostic codes (see Table 2) and the distribution of the data.2 For example, the most commonly recorded etiology code was spinal stenosis of the lumbar region (16.3%). The sample included some diagnostic codes with a small number of cases, therefore diagnostic codes were collapsed into NTSCD etiology categories for descriptive purposes. We used the following categories: degenerative disorder, infections, vascular, oncology malignant, oncology benign, oncology uncertain, inflammatory, inflammatory/infection, metabolic, congenital/genetic, and unspecified/unknown.24

Table 2.

Percent of ICD-10-CA diagnosis codes characterizing NTSCD etiology for patients in the “most likely NTSCD” group (n = 6,362)a(CONT.) a

Table 2.

Percent of ICD-10-CA diagnosis codes characterizing NTSCD etiology for patients in the “most likely NTSCD” group (n = 6,362)a a

Following the exclusions, acute care records with an NTSCD etiology ICD-10 code were identified, combined across fiscal year, and grouped together by patient using a unique patient identifier. Patients “most likely NTSCD” were defined as having at least one hospital admission with a NTSCD etiology code recorded as either the most responsible diagnosis or a pre-existing diagnosis. Patients with NTSCD diagnoses recorded as a “secondary diagnosis,” defined as a condition that is not the primary reason for the admission but a diagnosis for which the patient may or may not have received treatment or complication during hospital stay were classified as “probable NTSCD.”

Linking NTSCD etiology and neurological impairment (G code) records to determine type of record with paraplegia/tetraplegia diagnosis

In phase 1, hospital admission records with a diagnosis of paraplegia, tetraplegia, or cauda equina were identified and linked across fiscal year. This G-code data file, containing multiple records per patient, was joined to the data file containing NTSCD etiology diagnosis records using the unique patient identifier. Duplicate records were excluded and the remaining records were partitioned into 3 groups corresponding to (a) patients who had 2 contiguous acute care records representing diagnoses of NTSCD etiology and paraplegia/tetraplegia/cauda equine; (b) patients with only an acute care record with a NTSCD etiology diagnosis, who then continued on to phase 2; and (c) patients with no acute care record of NTSCD etiology but with a diagnosis of paraplegia, tetraplegia, or cauda equina (“possible NTSCD”). The latter group was considered excluded but was retained for future examination.

The purpose of phase 2 was to identify emergency department records and or inpatient rehabilitation records for paraplegia, tetraplegia, or cauda equina diagnoses that could be linked to an NTSCD etiology diagnosis recorded in acute care. Records with these medical diagnoses were extracted separately for each dataset and linked across fiscal year using the unique patient identifier. The earliest admission records from the NACRS and the NRS were joined to group b using the unique patient identifier.

Results

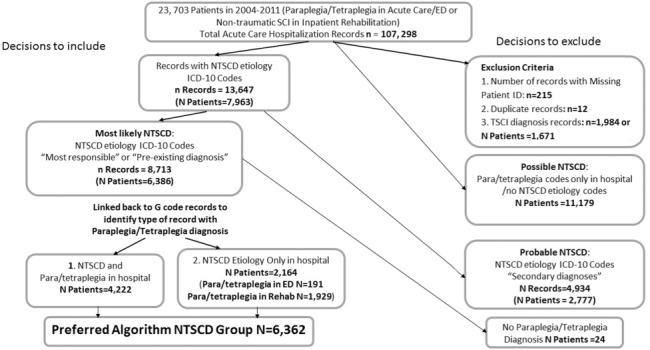

The process that was used to identify NTSCD cases is outlined in Figure 1. The original sample included 23,703 patients diagnosed with paraplegia, tetraplegia, or cauda equina in an acute care or inpatient rehabilitation hospital between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2011. Starting with records of all acute care hospitalizations (n = 107,298) during the time period for these patients, records of duplicate cases (n = 12), missing patient identifiers (n = 215), or a diagnosis of traumatic spinal cord injury (n = 1,984) were excluded. A total of 13,647 records representing 7,963 patients with an NTSCD etiology code were identified from the remaining records. From this subset, a record was identified as “most likely NTSCD” if a diagnostic code for a condition known to cause NTSCD was recorded as the most responsible/primary reason for hospital admission or was listed as a pre-existing diagnosis at admission. A total of 8,713 records representing 6,386 patients were deemed to be in the “most likely NTSCD” cohort. If NTSCD was recorded as only a secondary diagnosis, then that patient was considered “probable NTSCD” (n = 2,777). From the initial cohort with neurological impairment, we also identified 11,179 patients as “possible NTSCD” since they had no NTSCD diagnosis during the study period.

Figure 1.

Decision-making process to identify non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction (NTSCD) cases from health administrative data. ED = emergency department; ICD-10 = International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision; SCI = spinal cord injury; TSCI = traumatic spinal cord injury.

We then examined whether coding of neurological impairment was found in the acute care hospital, inpatient rehabilitation, or emergency department record. For 24 patients, we could not identify a corresponding record with neurological impairment, leaving a total of 6,362 patients. There were 4,222 patients with neurological impairment and NTSCD diagnosis recorded in acute care, 1,929 patients had their neurological impairment identified in an inpatient rehabilitation record, and 191 patients in an emergency department record.

Discussion

Estimating the incidence and prevalence of NTSCD continues to be a challenge for researchers in the spinal cord research field. The majority of studies have only included cases treated in rehabilitation or spinal units1,3,10–23; however, many patients with non-traumatic causes are not triaged to such units. There may have been referral bias and some patients may have sought treatment elsewhere or died before admission to a rehabilitation unit given the wide range of NTSCD etiologies. For instance, those with minimal neurological impairment or with terminal cancer-related NTSCD requiring palliative treatment are less likely to be admitted to a spinal unit.25 To accurately estimate the incidence and prevalence of NTSCD, population-based studies are needed.

To facilitate population-based research, the primary objective of this study was to assess the feasibility of identifying patients with NTSCD using national health administrative databases in Canada. The first stage determined the likelihood of whether the paraplegia or tetraplegia was non-traumatic. Non-traumatic causes were conceptualized based on a list of etiology ICD-10 codes drawn from the International NTSCI dataset.24 An algorithm combined multiple records per patient to identify the etiology of the disease associated with a neurological impairment (paraplegia, tetraplegia, and cauda equina) and then a series of decisions determined whether the patient met our criteria for a diagnosis of NTSCD. We determined that a confirmed case of NTSCD would require (1) a relevant diagnostic code for paraplegia, tetraplegia, or cauda equina syndrome recorded at admission to either acute care, emergency department, or inpatient rehabilitation; and (2) a diagnostic code for a condition known to cause NTSCD recorded as the most responsible/primary reason for hospital admission or listed as a pre-existing condition at admission.

Access to acute care, emergency department, and inpatient rehabilitation records enabled us to examine where neurological impairment was recorded. Interestingly, the results of our analyses suggest that both acute care and inpatient rehabilitation records are needed to identify a more comprehensive set of cases of NTSCD from administrative data sources. Approximately one-third of our “most likely NTSCD” cases had neurological impairment coded only in the inpatient rehabilitation data rather than during an acute care admission or emergency department visit. The remaining approximately two-thirds of patients had both NTSCD diagnosis and neurological impairment recorded in acute hospital records. Possible explanations are that the recording of neurological impairment in Canadian administrative data is not mandatory and that clinicians in the inpatient rehabilitation setting are more likely to assess level of neurological impairment and hence code it. This suggests that both acute care and inpatient rehabilitation records are needed to prevent underestimation of the incidence of NTSCD in the Canadian context. We are unsure if this may be the case for other jurisdictions; future incidence studies should consider these results.

In conducting this study, we faced a number of issues that warrant discussion and future research. One of the strengths of our approach is the use of the International Dataset for NTSCI etiology clas-sifications.24 This will facilitate comparisons with other studies, as a substantial difference between results can be partly explained by the lack of internationally accepted criteria for what etiologies of SCI constituted NTSCD at the time. We grouped various ICD-10 diagnoses as seen in Table 1 due to small numbers. These groupings will need validation with experts.

One of the biggest challenges to identifying cases of NTSCD in administrative data is the lack of clinical consensus regarding underlying causes of NTSCD.5 Further discussion among experts is critical not only to refining – and potentially expanding – the definition of which etiological conditions constitute NTSCD, but also to identifying methods or clinical markers for confirming a case.

Strengths/Limitations

The only other study that used an administrative database similar to ours was conducted in Victoria, Australia, with the hospital discharge database for the state from July 2000 to 2006.4 It is difficult to compare approaches, because at the time there were no internationally accepted criteria for etiologies of NTSCD and there are a number of differences between the Australian and Canadian coding of ICD-10. However, we have refined the approach by creating an episode of care using both the neurological impairment and possible NTSCD etiology through access to administrative data for acute care hospital admissions, emergency department visits, and inpatient rehabilitation admissions. For many records, the NTSCD etiology diagnosis and the diagnosis of neurological impairment were separate events. Without clinical data to provide knowledge of the clinical circumstances, we are making an assumption that these 2 events are linked, potentially resulting in falsely negative cases. Also, the first admission record with an etiology diagnosis was selected; however, patients may have been diagnosed with more than one NTSCD condition. Therefore, we do not know which disease resulted in neurological impairment.

Different coding guidelines may limit the use of our algorithm to identify NTSCD patients in other countries. However, the approach that we used of requiring a diagnosis of neurological impairment and an NTSCD etiology diagnosis to identify cases may be generalizable to other health care settings.

Conclusion

Despite the predicted increase in NTSCD, we do not have a grasp on the extent of NTSCD nationally or internationally. The results from this study are highly relevant and will contribute to understanding the epidemiology of NTSCD. We have proposed an algorithm for the identification of patients with NTSCD in health administrative databases. This feasibility study has the potential to inform future research initiatives to accurately determine the incidence and prevalence of NTSCD to establish the burden of disease and provide evidence-informed services.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Rick Hansen Institute, Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, Health Canada, and Western Economic Diversification Canada. Dr. Guilcher is a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Salary Award Recipient. Dr. Jaglal is the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute-University Health Network Chair at the University of Toronto.

The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Citterio A, Franceschini M, Spizzichino L, Reggio A, Rossi B, Stampacchia G.. Nontraumatic spinal cord injury: An Italian survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004; 85 9: 1483– 1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. New PW, Marshall R.. International Spinal Cord Injury Data Sets for non-traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2014; 52 2: 123– 132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCaughey EJ, Purcell M, McLean AN, . et al. Changing demographics of spinal cord injury over a 20-year period: A longitudinal population-based study in Scotland. Spinal Cord. 2015; 53 8: 1– 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. New PW, Sundararajan V.. Incidence of non-traumatic spinal cord injury in Victoria, Australia: A population-based study and literature review. Spinal Cord. 2008; 46 6: 406– 411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. New PW, Cripps RA, Bonne Lee B.. Global maps of non-traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: Towards a living data repository. Spinal Cord. 2014; 52 2: 97– 109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Noonan VK, Fingas M, Farry A, . et al. Incidence and prevalence of spinal cord injury in Canada: A national perspective. Neuroepidemiology. 2012; 38 4: 219– 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brinkhof MWG, Fekete C, Chamberlain JD, Post MWM, Gemperli A.. Swiss national community survey of functioning after spinal cord injury: Protocol, characteristics of participants and determinants of non-response. J Rehabil Med. 2016; 48 2: 120– 130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. New PW, Simmonds F, Stevermuer T.. A population-based study comparing traumatic spinal cord injury and non-traumatic spinal cord injury using a national rehabilitation database. Spinal Cord. 2011; 49 3: 397– 403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guilcher SSJT, Couris CM, Fung K, . et al. Health care utilization in non-traumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury: A population-based study. Spinal Cord. 2010; 48 Dec 2008: 45– 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. New PW, Reeves RK, Smith É, . et al. International retrospective comparison of inpatient rehabilitation for patients with spinal cord dysfunction: Differences according to etiology. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016; 97 3: 380– 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McKinley WO, Seel RT, Hardman JT.. Nontraumatic spinal cord injury: Incidence, epidemiology, and functional outcome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999; 80 6: 619– 623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Celani MG, Spizzichino L, Ricci S, Zampolini M, Franceschini M.. Spinal cord injury in Italy: A multicenter retrospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001; 82: 589– 596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. New PW. Functional outcomes and disability after nontraumatic spinal cord injury rehabilitation: Results from a retrospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005; 86 2: 250– 261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ones K, Yilmaz E, Beydogan A, Gultekin O, Caglar N.. Comparison of functional results in non-traumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2007; 29 15: 1185– 1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gupta A, Taly A, Srivastava A, Murali T.. Non-traumatic spinal cord lesions: Epidemiology, complications, neurological and functional outcome of rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2009; 47 4: 307– 311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osterthun R, Post MWM, van Asbeck FWA.. Characteristics, length of stay and functional outcome of patients with spinal cord injury in Dutch and Flemish rehabilitation centres. Spinal Cord. 2009; 47 4: 339– 344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lekoubou Looti AZ, Kengne AP, Djientcheu VDP, Kuate CT, Njamnshi AK.. Patterns of non-traumatic myelopathies in Yaounde (Cameroon): A hospital based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010; 81 7: 768– 770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCammon JR, Ethans K.. Spinal cord injury in Manitoba: A provincial epidemiological study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011; 34 1: 6– 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rouleau P, Ayoub E, Guertin PA.. Traumatic and non-traumatic spinal cord-injured patients in Quebec, Canada : 1. Epidemiological, clinical and functional characteristics. Open Epidemiol J. 2011; 4: 133– 139. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Den Berg MEE, Castellote JM, Mahillo-Fernandez I, De Pedro-Cuesta J.. Incidence of nontraumatic spinal cord injury: A Spanish cohort study (1972–2008). Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012; 93 2: 325– 331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ibrahim A, Lee KY, Kanoo LL, . et al. Epidemiology of spinal cord injury in hospital Kuala Lumpur. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013; 38 5: 419– 424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shin JC, Kim DH, Yu SJ, Yang HE, Yoon SY.. Epidemiologic change of patients with spinal cord injury. Ann Rehabil Med. 2013; 37 1: 50– 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang R, Guo L, Wang P, . et al. Epidemiology of spinal cord injuries and risk factors for complete injuries in Guangdong, China: A retrospective study. PLoS One. 2014; 9 1: 1– 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Biering-Sørensen F, Alai S, Anderson K, . et al. Common data elements for spinal cord injury clinical research: A National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke project. Spinal Cord. 2015; 53 4: 265– 277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Derrett S, Beaver C, Sullivan MJ, Herbison GP, Acland R, Paul C.. Traumatic and non-traumatic spinal cord impairment in New Zealand: Incidence and characteristics of people admitted to spinal units. Inj Prev. 2012; 18 5: 343– 346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]