Abstract

Behavioral momentum theory posits a paradoxical implication for behavioral interventions in clinical situations using Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behavior (DRA): When alternative reinforcers are presented within the same context as the problem behavior, the added reinforcers may decrease the frequency of the behavior but also increase its persistence when the intervention ends. Providing alternative reinforcers in a setting that is distinctively different from that in which the target behavior occurs may avoid or reduce this increase in persistence. The present experiment compared behavioral persistence following standard DRA versus DRA in a different context that was available after refraining from target behavior (Differential Reinforcement of Other Behavior, DRO). We arranged a human laboratory model of treatment intervention using computer games and token reinforcement. Participants were five individuals with intellectual disabilities. Experimental phases included (a) an initial multiple-schedule baseline with token reinforcement for target behaviors A and B, (b) an intervention phase with alternative reinforcement using a conventional DRA procedure for A and a DRO-DRA procedure for B, and (c) an extinction phase with no interventions and no tokens. Response rates as proportion of baseline in the initial extinction phase were greater for A than for B for three of five participants. Four participants whose response rates remained relatively high during the extinction phase then received a second extinction-plus-distraction test with leisure items available. Response rates were greater for A than for B in three of four participants. The results indicate that DRO-DRA contingencies may contribute to reduced post-intervention persistence of problem behavior.

Behavioral momentum theory (Nevin & Grace, 2000) holds that the persistence of some ongoing target behavior depends directly on the rate of reinforcement obtained in the presence of a distinctive stimulus, regardless of whether (a) all reinforcers are obtained by the target response, (b) some portion of those reinforcers are presented independently of the target response, or (c) even when those reinforcers are obtained by an explicit alternative response. Support for this conclusion has been obtained in a number of different experimental arrangements, for subjects including goldfish, humans, pigeons, and rats; the humans include children and adults, some of whom have intellectual or developmental disabilities. Reinforcers have included biofeedback signals, points or tokens, and edibles for the humans, in addition to the usual food or water reinforcers used with nonhuman animals. In addition, similar results have been obtained with reinforcers that are the same as or different from those maintaining target behavior. For summaries and reviews see Craig, Nevin, & Odum (2014); Dube, Ahearn, Lionello-DeNolf & McIlvane (2009); Nevin & Wacker (2013).

There is a paradoxical implication for behavioral interventions in clinical situations. Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behavior (DRA) is a widely used and often effective way to reduce problem behavior (reviewed in Petscher, Rey, & Bailey, 2009; Rooker, Jessel, Kurtz & Hagopian, 2013). However, if alternative reinforcers are presented within the same context as problem behavior, those added reinforcers, although intended to decrease problem behavior and replace it with socially desirable behavior, may actually increase the persistence of problem behavior when the intervention ends. Indeed, this perverse outcome has been obtained by Mace et al. (2010) during interventions with children exhibiting problem behavior.

Mace et al. (2010) suggested that increased persistence of target behavior could be avoided by reinforcing alternative behavior in a distinctively different context and obtained supporting data in a stimulus-compounding test during extinction with rats and with human participants. Podlesnik, Bai, and Elliffe (2012) confirmed this finding in a similar paradigm with pigeons, and also found that target behavior recurred at a substantial rate when all reinforcement was discontinued (relapse), suggesting some residual strengthening effect of alternative reinforcers on target behavior.

This paper is part of a series of studies evaluating alternative reinforcement in the presence of a different stimulus context that is available only after target behavior does not occur for some specified time (Differential Reinforcement of Other Behavior, DRO); hereafter, the DRO-DRA paradigm. The ultimate goal is to contribute to the development of treatment procedures that reduce or eliminate post-treatment relapse in clinical application for children with severe problem behavior. The first study in the series involved animal modeling with pigeons. The procedures included extinction of previously reinforced target-key pecking, access to a distinct stimulus context for meeting a DRO contingency, and reinforcement for alternative key pecks (DRA) in that context. Results showed (a) the DRO-DRA treatment reduced reinstatement of target-key pecking relative to a no-treatment control condition, and (b) less resurgence in the DRO-DRA treatment than in a standard-DRA treatment when alternative reinforcement was discontinued (Craig et al., submitted). Here, we describe a translational study in which children who had intellectual disabilities played computer games in multiple schedules with token reinforcers. In one component, alternative reinforcers were presented in a distinctively different situation that was accessed by refraining from analog problem behavior. In a second component, alternative reinforcers were presented within the same situation as analog problem behavior, with reinforcer rates yoked between components. Thus, the role of the DRO-DRA contingencies and different stimulus context could be compared directly with the potential strengthening effect of alternative reinforcers in conventional DRA within subjects and sessions.

Method

Participants

Six individuals with intellectual disabilities who attended a private school participated in this study. Each participant’s gender, chronological age, Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 4 mental-age equivalent score (PPVT; Dunn, Dunn, & Pearson Assessments, 2007), and diagnosis are listed in Table 1. A trained research assistant administered the PPVT and clinical diagnoses were obtained from student records.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Participant | Gender | Age | PPVT | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDY | F | 20 | 6:1 | Autism |

| SWN | M | 21 | 3:0 | Autism |

| DNL | M | 19 | 2:11 | PDD |

| RBG | M | 20 | 5:1 | Autism |

| HDS | M | 21 | 7:11 | PDD |

| AEA* | M | 17 | 2:7 | Autism |

Note. Age = years. PPVT = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 4 Mental age equivalent score (years:months). Diagnosis obtained from student records; PDD = Pervasive Developmental Disability.

AEA did not complete the experiment.

Apparatus and Setting

Sessions were conducted in a 1.5 × 1.8 m laboratory testing room located at the participants’ school. Figure 1 shows the layout. Participants were seated facing three adjacent walls. Each wall was 91 cm wide and the left and right walls were set at a 120-degree angle to the center wall. A narrow shelf along all three walls was 18 cm deep and 72 cm above the floor. At the right side of the center wall there was a 11 x 13 cm opening to a receptacle, 15 cm deep, into which tokens were dispensed by an automated poker-chip dispenser (Med ENV-703).

Figure 1.

Diagram of the experimental space from above (top) and in front (bottom) as configured for Phase II of the experiment. The diagram is not drawn to scale. T = token receptacle. M1 = Monitor 1 with gray keyboard and trackball; Games A and C were displayed in the left and right halves, respectively. M2 = Monitor 2 with white keyboard; Game B was displayed in the right half. M3 = Monitor 3 with mouse; Game D was displayed in the left half. See text for further details.

The right-side wall contained Monitor 1, a 17″ LCD color monitor flush-mounted above the shelf, 28 cm to the right of the token receptacle. During all phases of the experiment a modified keyboard was located on the shelf in front of Monitor 1; all of the keys had been removed except for the up and down cursor keys, and the rest of the keyboard was completely covered with white duct tape. In Phase II of the experiment, a trackball and button in a 11 x 14 cm housing were added, located on the shelf to the right of the keyboard. Monitor 2 was a 15″ LCD color monitor on the shelf in front of the center wall, 28 cm to the left of the token receptacle. During all phases of the experiment a second modified keyboard was placed in front of Monitor 2 on a small table that protruded 30 cm just below the shelf; all of the keys had been removed except for the left and right cursor keys, and the rest of the keyboard was completely covered with gray duct tape. In Phase II of the experiment, Monitor 3, also a 15″ LCD color monitor, was located on the shelf in front of the left-side wall, 38 cm to the left of Monitor 2, with a one-button computer mouse on the shelf just to the right of Monitor 3. Speakers were flush mounted in the right-side wall on both sides of Monitor 1, and small speakers were located on the shelf behind Monitors 2 and 3.

Experimental stimuli were computer games presented on the monitors (details below). All stimulus presentations, response recording, and token dispenser activations were managed by custom software written in Python and running on an array of four laptop computers configured as a local area network linked via Cat5 cables and a hub. These computers and the token dispenser were located behind the center wall of the laboratory where the experimenter sat during sessions. A small wide-angle video camera mounted near the ceiling within the lab allowed the experimenter to observe the participant and stimuli on the monitors during sessions.

Stimuli and Responses

The stimuli included four open-source computer games, written in Python, and downloaded from http://www.pygame.org/tags/arcade. We attempted to maximize discriminability of the multiple-schedule components by selecting games with numerous differences in auditory and visual characteristics and by programming different response topographies for each game. The games were modified for this application to simplify them, remove any score-keeping displays, restrict the display to half of a monitor screen, and conform to the experimental contingencies. For Game A (Pickup Truck), the participant moved an onscreen truck icon up and down at the right side of the screen by pressing the up and down cursor keys on a modified keyboard. An assortment of targets moved from left to right on the screen and disappeared if the truck hit them. For Game B (Seal Tree), the participant moved an onscreen clown icon left and right at the bottom of the screen by pressing the left and right cursor keys. Seal targets moved from top to bottom on the screen and stuck to the clown if they made contact with it. For both Games A and B, the keyboard auto-repeat function was disabled, and each key press was recorded as one response. Games C and D were shooting games (Smiley Blast and Duck Hunt, with assignment as Game C or D counterbalanced across participants). The participant used a trackball or mouse to position an on-screen cursor shaped like a gunsight and fired at moving targets on the screen by pressing the trackball button or mouse button. If the gunsight was superimposed on a target when the button was pressed, the target exploded (Smiley Blast) or fell to the bottom of the screen (Duck Hunt). Each button press was recorded as one response. During the experiment, responses were reinforced with tokens on VI schedules. All responses were eligible for reinforcement, regardless of whether they accomplished the game’s objective; for example, in the shooting games reinforcers could follow either hits or misses. During token deliveries, a 3-s chime sound was superimposed on the game’s sound track.

Procedure

Token exchange procedure and training

Throughout the experiment, accumulated poker-chip tokens were exchanged for snack food items immediately after each session. Food items for each participant were based on recommendations from classroom teachers. The exchange area was outside of the testing room. Four clear plastic containers were arranged in a row on a countertop, each with a supply of different food items. A clear plastic tube that held 10 tokens was placed in front of each container. During token exchange training, participants were taught by verbal instructions or modeling to select a container and fill the tube in front of it with tokens. The experimenter then exchanged the tokens for a small amount of the food item within the container. This was repeated until all tokens had been exchanged.

Reinforcer function test

A preliminary test determined whether presentation of tokens functioned as a conditioned reinforcer (as in Sweeney et al., 2014). This test was conducted on a 15″ color touch screen monitor located in a different testing room from the experiment. Each test session consisted of two 1-min sampling components presenting individual stimuli, followed by one 3-min choice component with both stimuli presented concurrently. In the first component, a 4-cm purple star appeared on the left side of the computer screen and touching it produced a token on a fixed-interval (FI) 2-s schedule. When the token was dispensed, the monitor screen displayed a 3-s animated fireworks display and 3 s of chimes presented through the speakers. During the second component, a 4-cm orange star was presented on the right side of the screen, and touching it did not produce any tokens (EXT). In the third component, both stars were displayed simultaneously with the same reinforcement contingencies just described and a 1.5-s changeover delay (COD). The dependent variable was the proportion of responding to the left side (tokens) during the 3-min concurrent-choice component. If at least 80% of the responses were to the left side for one session, then sessions continued with the reinforcement contingencies and order of presentation for the first two components reversed: The orange star on the right side was presented first for 1 min with tokens dispensed on FI 2 s, the purple star on the left side followed for 1 min with EXT, and the 3-min choice component presented both of these stimuli concurrently and with these schedules. Sessions continued until 80% of responses were made to the right side during the third component for one session, or to a maximum of five test sessions. All participants met both criteria within three sessions.

Preliminary game training

Training to play the computer games was conducted within the testing room but in a location that was different from any of the games during the rest of the experiment. A 15″ monitor and appropriate input device were placed on a small table in the center of the room. No other monitors or input devices were present, and a plain panel covered Monitor 1 so that it was not visible. All training sessions were 3 min in duration and participants were given three or four sessions within the same day. The software was programmed to dispense tokens on VI 10 s, and the experimenter also used a hand-held switch to provide additional tokens during the early part of training. During the initial session(s) for each game, the experimenter entered the testing room and introduced the game by verbal instructions, gestural prompts and occasional manual guidance, and provided verbal praise for responses. When the participant began to respond to the game reliably, the experimenter left the testing room. The criterion to complete training for each game was one session with all responses independent and a response rate of at least 20 per min. All participants met these criteria within 11 training sessions with one exception: Participant AEA engaged in high rates of manual stereotypy that interfered with playing the games. During six training sessions his mean response rate was 5.6 per min with occasional prompts and 2.6 per min independently, and he was excused from the experiment.

For the remainder of the experiment, sessions were conducted once per day, usually four or five days per week. Table 2 summarizes the apparatus and contingencies for the experimental conditions.

Table 2.

Apparatus and Experimental Conditions

| Condition | Monitor 1 Left Half |

Monitor 1 Right Half |

Monitor 2 Right Half |

Monitor 3 Left Half |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I Baseline | Game A White keyboard VI 32 s | Black screen No trackball | Game B Gray keyboard VI 32 s | No monitor or mouse |

| Phase II Treatment | Game A White keyboard EXT | Game C Trackball VI 8* s | Game B Gray keyboard EXT | Black screen Mouse If Game B DRO, then 15 s Game D VI 8 s |

| Phase III Extinction | Game A White keyboard EXT | Black screen No trackball | Game B Gray keyboard EXT | No monitor or mouse |

The VI schedule for Game C was adjusted across sessions to approximately equate obtained reinforcement for Games C and D.

Phase I: Baseline

All sessions consisted of four components alternating between Games A and B (ABAB or BABA). Responses to Games A and B modeled problem behavior that would be targets for treatment interventions in Phase II. Game A was displayed in the left half of Monitor 1 and Game B in the right half of Monitor 2, equidistant from the token receptacle; the unused portions of the monitor screens were black. During Phase I, Monitor 3 and the trackball and mouse for Games C and D were not present in the testing room.

The VI schedules, inter-component interval (ICI), and longer session durations for Phase I of the experiment were introduced gradually over four introductory sessions. In the first introductory session, component duration was 90 s, the ICI was 5 s, and the token schedule was VI 5 s. During ICIs, the stimuli disappeared and the screens were black. Over the next three introductory sessions the component duration was gradually increased to 150 s, the ICI to 20 s, and the schedule was thinned to VI 20 s.

For the remaining Phase-I Baseline sessions, component duration was 210 s, the ICI was 20 s, and the schedule was VI 32 s. Phase I continued for at least six more sessions and until response rates for the last six sessions appeared stable to visual inspection.

Phase II: Treatment

The structure of Phase II (treatment) sessions was similar to baseline sessions, with four 210-s components and 20-s ICIs, alternating between Games A+C and B+D. Monitor 3 and the input devices for Games C and D were present, and thus the testing room included three monitors and four input devices (the two modified keyboards for Games A and B, the trackball for Game C, and the mouse for Game D). Phase II continued for a minimum of 12 sessions and until response rates for the last six sessions appeared stable to visual inspection.

One component (Games A+C) modeled conventional DRA treatment in which the stimuli related to added reinforcers were displayed within the same stimulus context as the target behavior. Game A appeared on the left half of the Monitor 1 screen, as in the Phase-I baseline. The consequence for Game A was EXT (modeling extinction of target behavior); responses to the keyboard moved the on-screen icon, but nothing happened if it hit anything else on the screen and keyboard responses were never followed by tokens. Game C appeared in the right half of the Monitor 1 screen, and trackball button presses were followed by tokens initially on a VI 8 s schedule (modeling rich reinforcement for an alternate response). The VI schedule for Game C was adjusted from session to session to approximately equate obtained reinforcement for Games C and D. Games A and C were presented concurrently with a 1.5-s COD for changeovers from Game A to C.

The other component (Games B+D) modeled the DRO-DRA treatment approach in which meeting a differential reinforcement of other behavior (DRO) contingency resulted in access to added reinforcers in a stimulus context that was different from that of the target behavior. At the beginning of the component, Game B appeared on the right half of the Monitor 2 screen, as in Phase I, and Monitor 3 was dark. The consequence for Game B was EXT; responses to the keyboard moved the on-screen icon, but nothing happened if it contacted anything else on the screen and keyboard responses were never followed by tokens. In the first session, a 1-s DRO contingency was in effect for Game B; if the participant did not emit a keyboard response for 1 s, then Game D appeared in the left half of the Monitor 3 screen (38 cm to the left of Monitor 2) for 15 s and mouse button presses were followed by tokens on a VI 8 s schedule, while Game B remained displayed on Monitor 2. While both games were presented concurrently there was a 1.5-s COD for changeovers from Game B to D. After 15 s, Game D disappeared and the DRO contingency was again in effect for Game B. The duration of the DRO requirement was increased over the first few sessions until (a) it was at least 3 s, (b) it was at least 300% of the mean inter-response time for the last six Phase-I baseline sessions, and (c) the response rate for Game B decreased to less than 10% of the mean rate for the last six Phase-I baseline sessions.

Phase III: Extinction

Session structure and apparatus were identical to Phase I baseline. The EXT contingencies for both Games A and B were the same as those of Phase II: Responses to the keyboards moved the on-screen icons, but nothing happened if they made contact with anything else on the screen and keyboard responses were never followed by tokens.

If response rates decreased to less than 10% of baseline for both games, then a reinstatement probe was conducted. For one session, two response-independent tokens were dispensed within the first 10 s of Games A and B.

Extinction plus distraction

If response rates for both Games A and B did not decrease to less than 50% of baseline within three sessions, then the Phase II condition resumed for a minimum of six sessions. The extinction condition described above was then repeated, but with the addition of a concurrent distracting stimulus (e.g., Mace et al., 1990). We asked caregivers to suggest items of interest to the participant (e.g., videos), and these items were made available within the testing room during the experimental sessions, beginning 20 s before the first component and continuing throughout the session, including the ICIs.

Phase IV: Reconditioning

After extinction phases were complete, the initial baseline conditions were reinstated for two sessions.

Results

Phase I: Baseline

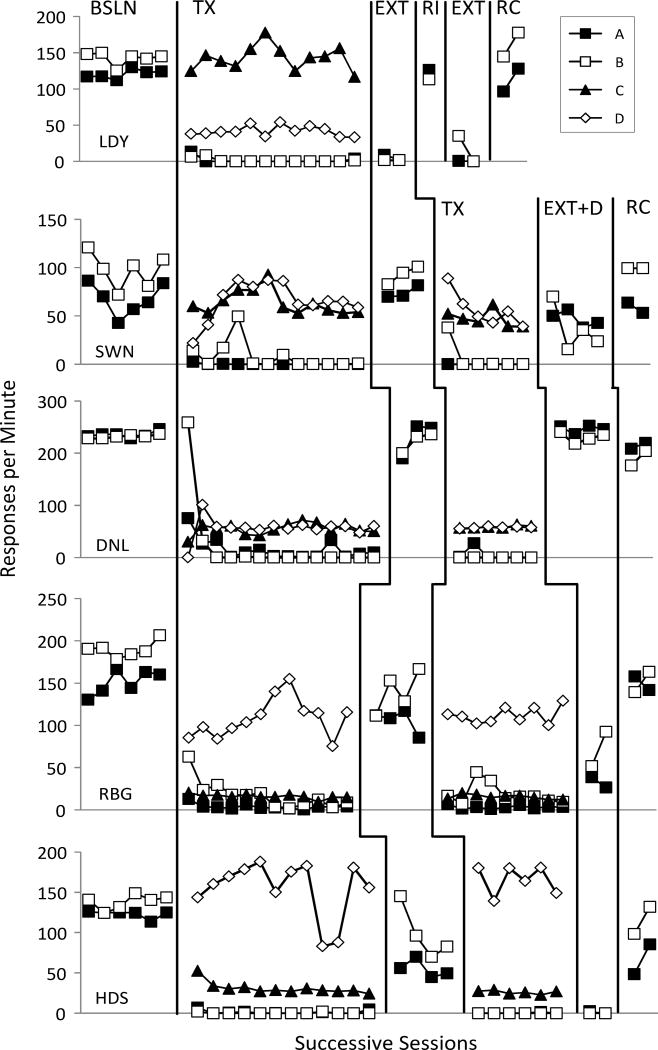

All five participants completed the four introductory baseline sessions with response rates of at least 50 per min. The leftmost portions of each plot in Figure 2 show mean response rates per session for the last six sessions of the baseline phase.

Figure 2.

Response rates per minute in all conditions for Games A, B, C, and D. Condition labels: BSLN = Baseline, TX = Treatment, EXT = Extinction, RI = Reinstatement probe (Participant LDY only), EXT+D = Extinction plus distraction (Participants SWN, DNL, RBG, and HDS only), RC = Reconditioning.

Phase II: Treatment

The duration for Phase II was 12 sessions for all participants except Participant DNL, who was given two additional sessions following a school vacation. For Participants SWN and DNL, response rates were similar for Games C and D. The other participants’ rates were substantially higher for one game than the other because of individual differences in the way participants interacted with the games. The data in Figure 2 show, however, that both DRA (Game A+C) and DRO-DRA (Game B+D) were successful intervention models. Response rates for Games A and B immediately fell to near zero for Participants LDY and HDS, and mean response rates during the first six sessions were 15% of baseline or less for the remaining participants, with Game-B rates slightly higher than Game-A rates. One exception was DNL’s first session because he did not pause long enough on Game B to contact the DRO contingency until his second session. During the last six sessions of Phase II, mean target response rates for Games A and B were less than 5% of baseline for all participants. Overall, the DRA and DRO-DRA intervention models were equally effective.

During Phase II the VI schedule for Game C was adjusted on a session-to-session basis to approximately equate obtained reinforcement for Games C and D; the range of VI values was 5 to 16 s. The data in Table 3 show that obtained reinforcement for Games C and D during Phase II was approximately equal. The top row of data for each subject shows the initial Phase II condition, and the second row shows the second Phase II condition for those participants who received the extinction plus distraction condition.

Table 3.

Obtained Reinforcement for Games C and D during Phase II

| Total Tokens All Sessions | Mean Tokens / min Last 6 Sessions |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | Game C | Game D | Game C | Game D |

| LDY | 400 | 400 | 4.60 | 4.71 |

| SWN | 384 | 386 | 4.93 | 5.00 |

| 192 | 191 | 4.57 | 4.55 | |

| DNL | 444 | 445 | 4.86 | 4.98 |

| 200 | 201 | 4.79 | 4.76 | |

| RBG | 379 | 375 | 4.69 | 4.64 |

| 282 | 302 | 4.17 | 4.98 | |

| HDS | 447 | 449 | 5.07 | 5.10 |

| 225 | 219 | 5.36 | 5.21 | |

Phase III: Extinction

The top plot in Figure 2 (EXT) shows that Participant LDY’s response rates for both Games A and B fell to zero within two sessions. Because of this, she received a reinstatement probe (RI) and responding to Games A and B recovered. In two subsequent extinction sessions, response rates again declined to zero within two sessions. For the other four participants, the data in Figure 2 for the initial extinction phase (EXT) show very little change from baseline response rates (SWN and DNL) or only moderate decreases (RBG and HDS).

Figure 3 shows response rates for successive 3.5-min components (two per session for each game) as proportion of the mean response rates during the last six baseline sessions. The first data point for each component at the onset of the phase shows that Game-A proportional rates were higher than Game-B rates for four of five participants (LDY, SWN, DNL, and RBG), although some of the differences were small. Figure 4 shows the initial component for each game in more detail, as proportion of baseline rate for successive 30-s blocks of time. This analysis shows LDY, DNL, and RBG with higher rates for Game A; SWN with a shift from higher to lower rates for Game A; and HDS with consistently higher rates for Game B.

Figure 3.

Response rate as proportion of baseline rate for successive components during the initial extinction condition for Games A and B. Condition labels for Participant LDY: EXT = Extinction, RI = Reinstatement probe. For Participants SWN, DNL, RBG, and HDS all data are from the extinction condition.

Figure 4.

Response rate as proportion of baseline rate for successive 30-s blocks of time during the first extinction component for Games A and B.

Results of LDY’s reinstatement probe are shown in the top panel of Figure 3 (RI), with higher proportional response rates for Game A. When the extinction contingencies were resumed for two sessions, the Game-B rates were higher in the first component, and then zero for both games.

The results for SWN and DNL in Figure 3 show that proportion of baseline rate was higher for Game A than for Game B in five of six components. For both of these participants, response rates increased to near or above baseline; SWN’s mean proportion of baseline for Games A and B was 1.10 and 0.95, respectively, and DNL’s was 0.98 and 0.96, respectively. For RBG and HDS, proportion of baseline rate was generally greater for Game B. For RBG mean proportion of baseline for Games A and B was 0.70 and 0.74, respectively, and for HDS it was 0.36 and 0.57, respectively.

Extinction plus distraction

Because response rates for SWN, DNL, RBG, and HDS during the initial extinction phase did not decrease to less than 50% of baseline for both games, the Phase II procedures were reinstated in preparation for the extinction plus distraction condition. During the return to Phase II, Figure 2 shows that response rates for SWN, DNL, and HDS were similar to the initial Phase-II condition for six sessions. RBG’s response rates for Game A increased in the third and fourth sessions to more than 10% of baseline, and he was given additional sessions to recover the earlier Phase-II results. The extinction condition was then repeated with concurrent distracting stimuli. These stimuli were: SWN, videos on an iPad; DNL, sand tray and videos on an iPad; RBG, streaming video of a TV show and picture books; HDS, computer games on an iPod or videos on an iPad.

Figure 2 shows that response rates during extinction plus distraction (EXT+D) were lower than the initial extinction phase for SWN, RBG, and HDS, but unchanged for DNL. Figure 5 shows response rates for successive 3.5-min components (two per session for each game) as proportion of the mean response rates during the last six baseline sessions. Results for SWN again showed higher proportion of baseline rate for Game A than B, means of 0.70 and 0.37, respectively. Results for DNL were very similar to the first extinction condition, with no reduction in response rate and slightly higher proportion of baseline for Game A than B; means were 1.05 and 0.99, respectively. Results with RBG were also similar to the first extinction condition, with mean proportion of baseline for Games A and B of 0.22 and 0.27, respectively. Results for HDS were very different from the first extinction condition, with only one brief response bout for Game A, and mean proportion of baseline for Games A and B of 0.01 and 0.0, respectively.

Figure 5.

Response rate as proportion of baseline rate for successive components during the extinction plus distraction condition for Games A and B.

Phase IV: Reconditioning

The VI 32 s baseline reinforcement schedule was resumed for two sessions following the extinction tests. The data in the rightmost portion of Figure 2 (RC) show that response rates recovered to at least 80% of baseline within two sessions, with the sole exception of 70% for HDS, Game A.

To summarize the results, response rates in EXT as proportion of baseline were greater for Game A than Game B: (a) in three of five participants during the first component of the initial extinction test (LDY, DNL, RBG; Fig. 4), (b) in three of five participants across all components of the initial extinction test (LDY, SWN, DNL; Fig. 3), (c) in the only reinstatement probe (LDY, Fig. 3), and (d) in three of four extinction plus distraction tests (SWN, DNL, HDS; Fig. 5). Thus, the majority of the results for each analysis indicated greater persistence for Game A, although (a) there was variability within some individuals (LDY in first vs. second EXT, HDS in EXT vs. EXT+D), (b) some of the differences in the predicted direction were small (LDY in first EXT, DNL and HDS in EXT+D), and (c) in some cases response rates were very close to baseline rates despite procedural extinction by the suspension of token deliveries (SWN, DNL, and RGB in EXT; DNL in EXT+D).

Discussion

During extinction challenges, there was generally less resurgence of target behavior following the laboratory model of DRO-DRA treatment (Game B+D) than the model of conventional DRA treatment (Game A+C). This outcome is consistent with the predictions of behavioral momentum theory as extended to resurgence by Shahan and Sweeney (2011).

It is also consistent with recent research. Resurgence refers to the difference in proportions of baseline between the initial sessions of extinction and the immediately preceding sessions of treatment. In the present study there was less resurgence in the DRO-DRA component for three of the four participants who received the extinction plus distraction test (SWN, DNL, HDS, Fig. 2), although the overall magnitude of resurgence was very low for HDS and high for DNL, so the differences were small. Comparable data have been obtained with pigeons. Craig et al. (submitted) performed a similar comparison within subjects between standard DRA and DRO-DRA in successive conditions presented in counterbalanced order. Conventional DRA and DRO-DRA were equally effective in decreasing target responding to near zero as found here. In an extinction test following treatment, there was less resurgence in the DRO-DRA condition for five of six pigeons.

What might account for the variability of the data within and between subjects? We note that all participants except LDY continued to play the games during at least one EXT condition, suggesting that the games themselves provided intrinsic reinforcement which could counteract the absence of token reinforcement during tests. The magnitude of reinforcement for interacting with the different games was uncontrolled and likely to vary across individuals and perhaps with accumulating experience, thus contributing to the variability of the results within and between participants and, perhaps, reducing differences between DRO-DRA and conventional DRA.

Similar variability in outcomes has been reported in previous studies with human participants with intellectual disability. For example, Parry-Cruwys et al. (2011) found greater resistance to distraction following richer reinforcement schedules in only five of six special-education students engaged in various classroom tasks, again suggesting the possibility of interaction with task-related intrinsic reinforcers. Relatedly, Sweeney et al. (2014) found that between-subject variability in both pigeons and humans with intellectual disability was greater in conditions including analog sensory reinforcers.

Given that sensory consequences or intrinsic reinforcers are inevitably present in the interactions between organisms and their environment, research should be directed toward enhancing the potency of the contingencies in the DRO-DRA paradigm. In the present study, the DRO intervals were 3 s for all participants. This value was at least 300% of the mean inter-response time for the last six Phase-I baseline sessions, and the procedure was very effective for reducing the frequency of target behavior to zero or near-zero rates. The present study thus modeled the initial phase of treatment employing the DRO-DRA paradigm, with brief DRO requirements and frequent access to alternative reinforcement. One avenue for further research is to explore methods for increasing DRO durations and reducing the frequency or magnitude of alternative reinforcement to more practical levels.

How might clinicians incorporate elements of the DRO-DRA procedure into treatment interventions? In particular, how could one arrange a distinctive stimulus context for presenting DRA reinforcers? Colleagues in clinical research settings are currently evaluating DRO-DRA procedures. In these studies, the settings for DRA reinforcers may include features such as a different therapist, moving to a different room, and distinctive colors of walls, furniture, and therapists’ clothing. In one study in which the target behavior is automatically reinforced stereotypy, response blocking is used to minimize automatic reinforcement during the transition to and within the DRA setting. In general, preliminary results are consistent with those of the Craig et al. (submitted) study with pigeons and the present study in a human operant laboratory.

It is worth noting that the DRO-DRA contingencies are structurally similar to those arranged in “therapeutic-workplace” treatment of drug addiction (e.g., Silverman, 2004; Silverman, DeFulio, & Sigurdsson, 2012). Therapeutic-workplace interventions for drug abuse include an abstinence contingency common to contingency management treatment approaches (Higgins, Heil, & Sigman, 2013). The reinforcers contingent upon abstinence, however, are also contingent upon socially desirable behavior in a workplace environment that provides a stimulus context very different from that in which abuse has occurred. In the DRO-DRA procedure described in this paper the DRO contingency and the separate stimulus context of Game D are functionally equivalent to the abstinence contingency and workplace context of therapeutic-workplace interventions. The DRO-DRA laboratory model could be extended to study relapse of drug seeking after treatment has ended.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under award number R01HD064576 to the University of New Hampshire and P30HD004147 to the University of Massachusetts Medical School. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The third author was a member of the National Institute of Science and Technology on Behavior, Cognition, and Teaching (INCT-ECCE), and supported by a doctoral scholarship from the São Paulo Research Foundation, FAPESP 2011/12847-2 and 2015/08332-8; he thanks Deisy de Souza (INCT-ECCE Director) and his advisors Julio C. de Rose and Harry A. Mackay. The authors thank Dr. Christophe Gerard and Vadim Droznin for computer software; the Shriver Center’s Clinical and Translational Research Support Core for assistance with participant recruitment; and the staff and students of the New England Center for Children, Southborough, MA for their cooperation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

William V. Dube, E. K. Shriver Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School

Brooks Thompson, E. K. Shriver Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Marcelo V. Silveira, Departamento de Psicologia, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brasil

John A. Nevin, Department of Psychology, University of New Hampshire

References

- Craig AR, Cunningham PJ, Sweeney MM, Shahan TA, Nevin JA. Delivering alternative reinforcement in a distinct context reduces its counter-therapeutic effects on relapse. doi: 10.1002/jeab.431. Manuscript revised and submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AR, Nevin JA, Odum AL. Behavioral momentum and resistance to change. In: McSweeney FK, Murphy ES, editors. The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of operant and classical conditioning. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2014. pp. 249–274. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn DM Pearson Assessments. PPVT-4: Peabody picture vocabulary test. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Assessments; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dube WV, Ahearn WH, Lionello-DeNolf KM, McIlvane WJ. Behavioral Momentum: Translational research in intellectual and developmental disabilities. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2009;10:238–253. doi: 10.1037/h0100668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Sigmon SC. Voucher-based contingency management in the treatment of substance use disorders. In: Madden GJ, editor. APA handbooks in psychology. APA handbook of behavior analysis, Vol. 2: Translating principles into practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 481–500. [Google Scholar]

- Mace FC, Lalli JS, Shea MC, Pinter Lalli E, West BJ, Roberts M, Nevin JA. The momentum of human behavior in a natural setting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1990;54:163–172. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1990.54-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace FC, McComas JJ, Mauro BC, Progar PR, Ervin R, Zangrillo AN. Differential reinforcement of alternative behavior increases resistance to extinction: Clinical demonstration, animal modeling, and clinical test of one solution. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2010;93:349–367. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2010.93-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin JA, Grace RC. Behavioral momentum and the Law of Effect. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2000;23:73–130. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x00002405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin JA, Wacker DP. Response strength and behavioral persistence. In: Madden GJ, editor. APA handbooks in psychology. APA handbook of behavior analysis, Vol. 2: Translating principles into practice. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Parry-Cruwys DE, Neal CM, Ahearn WH, Wheeler EE, Premchander R, Loeb MB, Dube WV. Resistance to disruption in a classroom setting. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:363–367. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petscher ES, Rey C, Bailey JS. A review of empirical support for differential reinforcement of alternative behavior. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30:409–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podlesnik CA, Bai JY, Elliffe D. Resistance to extinction and relapse in combined stimulus contexts. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2012;98:169–189. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2012.98-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooker GW, Jessel J, Kurtz PF, Hagopian LP. Functional communication training with and without alternative reinforcement and punishment: An analysis of 58 applications. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:708–722. doi: 10.1002/jaba.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahan TA, Sweeney MM. A model of resurgence based on behavioral momentum theory. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2011;95:91–108. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2011.95-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K. Exploring the limits and utility of operant conditioning in the treatment of drug addiction. The Behavior Analyst. 2004;27:209–230. doi: 10.1007/BF03393181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, DeFulio A, Sigurdsson SO. Maintenance of reinforcement to address the chronic nature of drug addiction. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;55(1):S46–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM, Moore K, Shahan TA, Ahearn WH, Dube WV, Nevin JA. Modeling the effects of sensory reinforcers on behavioral persistence with alternative reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2014;102:252–266. doi: 10.1002/jeab.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]