Abstract

The existence of social inequalities in health is well established. One strand of research focuses on inequalities in health within a single country. A separate and newer strand of research focuses on the relationship between inequality and average population health across countries. Despite the theorization of (presumably variable) social conditions as “fundamental causes” of disease and health, the cross-national literature has focused on average, aggregate population health as the central outcome. Controversies currently surround macro-structural determinants of overall population health such as income inequality. We advance and redirect these debates by conceptualizing inequalities in health as cross-national variables that are sensitive to social conditions. Using data from 48 World Values Survey countries, representing 74% of the world’s population, we examine cross-national variation in inequalities in health. The results reveal substantial variation in health inequalities according to income, education, sex, and migrant status. While higher socioeconomic position is associated with better self-rated health around the globe, the size of the association varies across institutional context, and across dimensions of stratification. There is some evidence that education and income are more strongly associated with self-rated health than sex or migrant status.

The inverse relationship between social position and health – often referred to as the “health gradient” – is a central finding from decades of work on the social determinants of health (Cutler et al. 2006; House 2002; Kitagawa and Hauser 1973; Mirowsky and Ross 2003; Schnittker and McLeod 2005; Williams 1990; Williams and Collins 1995). Indeed, low social standing has been theorized as a “fundamental cause” of disease that reproduces the health gradient through time and space (Link and Phelan 1995; Phelan and Link 2005). Although various types of inequality can represent a fundamental cause, the greatest research focus has been on inequalities based on socioeconomic status. Research at the intersection of social inequality and health has tended to take two forms: on the one hand, researchers have examined individual-level inequalities in health within a single society, frequently United Kingdom and the United States (Goesling 2007; Lynch 2006; Marmot; Schnittker 2004; Warren 2004; Yang 2008), establishing social factors, such as income, education, gender or immigration status, as predictors of various health outcomes. On the other hand, researchers have explored the relationship between aggregate indicators of income inequality and aggregate health outcomes across multiple, but usually advanced, industrialized nations (Babones 2007; Beckfield 2004; Wilkinson 1995; Wilkinson and Pickett 2006), finding mixed support for the relationship between income inequality and population-health indicators such as life expectancy and infant mortality.

While research has focused on either inequalities in health within a single society or the relationship between inequality and health across societies, less is known about inequalities in health in comparative context (Beckfield 2004; Beckfield and Krieger 2009; Olafsdottir 2007). Cross-national comparison is essential because it can show how generalizable the relationship between inequality and health is at the individual level, and promote theoretical development and empirical testing of the broader social forces that shape health inequalities. For example, recent comparative work shows that generous family policies may have a positive impact on the health of parents in Iceland, while lack of such policies may negatively impact the health of parents in the United States (Olafsdottir 2007). Our goal in this paper is to advance the comparative turn in research on health inequalities by conceptualizing and analyzing health inequality itself (as generated by markers of social position such as education, income, sex, and migrant status) as a dependent variable. We illustrate the promise of this approach by developing cross-nationally comparable measures of health inequality, and describing the global variability in health inequalities. The results suggest that the multi-disciplinary debate over whether income inequality harms health (Beckfield 2004; Jen, Jones, and Johnston 2009; Kim et al. 2008; Wilkinson and Pickett 2006) can be extended in a new direction by investigating the determinants of inequalities in health.

Indeed, inequalities in health at the individual level are substantial, and income and education have been found to be key predictors of health outcomes. In general, those with lower levels of income and education experience worse health than those with higher levels (Mirowsky, Ross, and Reynolds 2000; Robert and House 2000; Schnittker and McLeod 2005). Sex differences are more complex, with women typically disadvantaged relative to men on measures of morbidity and mental health, but not mortality (Ross and Bird 1994). US-focused research shows that Blacks are disadvantaged relative to Whites across a range of health outcomes (Williams and Collins 1995). Consequently, we focus on four indicators when creating our measures of cross-national variation in health inequalities: income, education, sex, and minority status (proxied by being foreign-born, a measure that generalizes outside the US). This is an important first step, since relatively little is known about how the strong associations observed in the U.S. and selected other countries translate into a diverse sample of developed and developing countries (see Eikemo et al. [2008], Kunst et al. [2004], Mackenbach et al. [2008], and van Doorslaer and Koolman [2004] for studies of health inequalities in Europe). We also know relatively little about the macro-social factors that may differentially affect health inequalities based on social cleavages (Beckfield and Krieger 2009; Putnam and Galea 2008). After demonstrating the extensive cross-national variability of the health gradient, we then begin to explore the possible determinants of the health gradient. As noted, much of this research has focused on the impact of income inequality on health. While some researchers have enthusiastically supported the income inequality hypothesis (Wilkinson and Pickett 2006), others have failed to find supportive evidence (Beckfield 2004). Anticipating the arguments and evidence below, we argue for redirecting the debate on health and inequality by focusing on inequalities in health within and across countries rather than the relationship between inequality and health across countries (Olafsdottir and Beckfield 2011).

In this paper, we use World Values Survey (WVS) data to address two overarching research questions: First, how much do health inequalities based on social position vary across 48 societies? Second, does income inequality at the societal level impact those health inequalities? Our paper proceeds in three steps. First, we review the literature on the relationship between inequality and health, focusing on inequalities in health across multiple nations and highlight recent work suggesting what factors may account for cross-national variation in health inequalities. Second, we provide figures that evaluate the health gradient in a cross-national perspective. We begin by using binary logistic regression models to evaluate the effects of income, education, gender and migrant status on self-assessed health. We then create our new dependent variables and evaluate their relationships to income inequality. Third, in the concluding section we discuss some of the implications (and the limitations) of our results and provide suggestions for further research.

SOCIAL INEQUALITIES GENERATE HEALTH GRADIENTS

The “fundamental cause” perspective interprets the health gradient as a relationship between social position and health that reproduces itself through multiple mechanisms. Link and Phelan (1995) have directed health scholarship back to societal-level social inequality by arguing that social standing will always be linked to health because it represents a fundamental cause of disease, in that the impact of social standing on health cannot be eliminated by intervening on the mechanisms that link social standing to health disparities. The inverse relationship persists because access to resources (such as money, knowledge, power, and social networks) can be used to avoid health risks and to minimize the consequences of illness. This implies that mortality-reducing technologies and knowledge should steepen the health gradient, because the better-off can take advantage of them faster (Cutler et al. 2006; Lutfey and Freese 2005).

In this paper, we take the fundamental-cause approach as a point of departure for developing a comparative framework for theorizing health inequalities (see Olafsdottir [2007] for an approach that focuses on social inequality and the welfare state, and Beckfield and Krieger [2009] for a review of the nascent empirical literature). We argue that societies establish systems for the distribution of resources, social hierarchies that generate relative social comparisons, and institutional mechanisms for translating social and individual resources into health. This opens up new questions: how much (and why) do health inequalities vary across societies? Following the logic of the fundamental-cause approach, one would expect to observe substantial cross-national variation in health inequalities, such that one finds steeper health gradients in richer, healthier societies than in poorer, less-healthy societies, as people higher up the social hierarchy take disproportionate advantage of health-improving knowledge and technologies. Conversely, a case can be made that if social inequality translates into health inequality through mechanisms that vary in different social contexts, one would expect to observe constant health gradients across societies – especially, if, as we do below for income and education, one measures social standing on relative scales. That is, in addition to reproducing itself over time, an extension of the fundamental-cause perspective might anticipate that the health gradient is a constant across a heterogeneous set of places. Existing evidence shows significant health gradients in the United States (Adler et al. 1994; Krieger et al 2008; Mirowksy and Ross 2003; Ross and Mirowsky 1995; Ross and Wu 1995, 1996, Schnittker 2004; Williams 1990; Williams and Collins 1995) and most western European countries (Mackenbach et al. 2008), including the United Kingdom (Davey Smith et al 1990; Macintyre 1997; Townsend and Davidson 1982) and Finland (Lahelma, Rahkonen and Huuhka 1997).

Health gradients are not unidimensional, reflecting the fact that there are multiple dimensions of social standing and multiple ways in which people can gain access to resources (Graham 2007; House et al. 2005). Education, income, gender, and migrant status are all important cleavages in societies around the world. Education reflects social status in a broad manner and is related to both material and non-material resources (Lahelma 2001). There are several advantages associated with using education as a source of stratification in health research. It is broadly stable across the life-course, equally suitable for men and women, and more comparable across countries than occupation (Valkonen 1989). However, educational structures change over time (Lahlema 2001) and while perhaps more comparable than occupation, the meaning of education still varies across national contexts, especially, perhaps, between richer and poorer countries. Nevertheless, education is a crucial component of understanding why social class is related to health, since in addition to the material resources it may provide, it gives people knowledge that shapes their health behaviors that impact health and illness (Lahelma 2001).

While education is associated with social status, health behaviors, health-related knowledge, and material resources (Kingston et al. 2003; Mirowsky and Ross 2003), it is important to isolate the role of material resources, most directly measured by income. Family income is, despite some problems associated with the measure, an indicator of the material resources individuals and families have at their disposal (Lahelma 2001). Together, these two indicators provide insights into the material and non-material components of social standing that generate socioeconomic gradients in health. As Cutler and colleagues (2006:114) point out, it is important to estimate the effects of income and education separately, both because different mechanisms are at work, and because of the need to identify potential policy levers (see also Starfield 2006). Indeed, estimating income-based and education-based health gradients separately and comparing them in a broad cross-section of societies can shed light on whether economic resources or social status matters more for health, and how societal context itself might shape exactly how much resources and status matter for health.

While much of the cross-national work on health inequalities has focused on inequality based on socioeconomic status, it is important to consider other social cleavages that matter within and across societies. Research has shown that while women generally outlive men, they have worse health throughout the lifecourse (Verbrugge 1996). There may, of course, be some biological explanations for these differences, yet the largest part of the explanation can be found in the social roles assigned to men and women within societies. For example, research has indicated that women’s lifestyle protects their health, compared to men, but that their vulnerable position in the workplace and within the home contributes to their worse health outcomes throughout their lives (Ross and Bird 1994). Focusing on gender in a cross-national perspective, Bird and Rieker (2008) have developed the framework of constrained choice, highlighting how socially constructed social roles impact health behavior and health inequalities between men and women across the globe. They particularly highlight the importance of social policies as a possible mechanism equalizing health across genders, a point that is supported by the impact of family policies on health of parents in Iceland (Olafsdottir 2007).

Within the U.S., much of the literature on health disparities focuses on racial and ethnic differences in health outcomes. As expected, minority groups that are vulnerable in society often experience worse health than groups that hold a more advantageous position in society and research consistently shows that African Americans experience some of the worst health outcomes in the U.S. whereas whites and Asian Americans generally have better health outcomes. Perhaps contradictorily, research has indicated that immigrants are often healthier than their native counterparts, but this difference decreases the longer a person resides in the United States. This has been explained both by positive impact of health selection and the negative impact of acculturation. As many of the countries that are included in the World Values Survey do not have a similar history of multiple racial/ethnic groups living in the society, the survey does not have particularly good measures on race and ethnicity. Therefore, we rely on whether the respondent is an immigrant and look at whether that status results in better or worse health across our 48 countries.

Our first analytical step, then, is to examine the variation in the health inequalities based on social position in our sample of 48 countries. Drawing on the extensive literature that shows that those who have less education or less income have worse health outcomes, our Universal Gradient Hypothesis (H1) predicts an inverse relationship between education and health, and between income and health, in all 48 nations.

DOES INCOME INEQUALITY GENERATE HEALTH INEQUALITES?

The scholarship reviewed above has convincingly established that disadvantaged individuals in many affluent democracies have worse health than those in more advantageous positions. That is, there is consensus on the existence of social inequalities in health within many societies. Conversely, there is an ongoing, heated debate among comparative health researchers over whether the level of income inequality in a society is associated with aggregate, societal-level measures of population health such as the infant mortality rate and life expectancy (Beckfield 2004; Jen et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2008; Wilkinson and Pickett 2006). That is, there is dissensus on the existence of a relationship between inequality and health. To take a recent characterization of the debate, Zimmerman (2008) colorfully notes that research on the association between inequality and health is now generating “far more heat than light, with two dug-in sides lobbing analyses back and forth with increasing sophistication and decreasing effect” (Zimmerman 2008:1882). We argue that one way to generate some light is to examine whether and to what degree economic inequality in a society influences inequalities in health.

We anticipate that economic inequality within and among societies should be related to inequalities in health within societies. Researchers interested in comparative health care systems noted in the 1970s that inequality in capitalist societies creates and sustains health disparities (McKeown 1979; Navarro 1976), which gives reason to believe that some societies may have more health inequality than others, especially where market relations predominate. Moreover, there are dramatic differences between richer and poorer countries in aggregate measures of population health (Brady, Kaya and Beckfield 2007; Goesling and Firebaugh 2004), which is another reason to believe that social inequalities in the health of populations could differ dramatically across societies at very different levels of economic development. Following the logic of the fundamental-cause approach outlined above, we would expect steeper health gradients in richer societies. Comparative researchers have pointed out various societal factors, such as social inequality, that may impact health inequalities within and across countries (Beckfield and Krieger 2009; Kunitz 2007; Kunitz and Pesis-Katz 2005; Olafsdottir and Beckfield 2011; Wilkinson 1996). However, this association has neither been systematically tested across multiple national contexts, nor has the focus been on the relationship between economic inequality and social inequalities in health.

We argue that economic inequality should be positively associated with the level of inequality in health in a society. Here, we can imagine that the effect of individual income on individual health is the same in two societies, but one has higher levels of income inequality, making the association between income and health stronger, mechanically, in the higher-income-inequality society. In addition, individuals with either educational or income advantage in a higher-income-inequality society, may have even more resources that they can translate even more effectively into better health, and the poor would be even more deeply disadvantaged (Evans, Hout and Meyer 2004; Hout and Fisher 2003). Furthermore, if income serves as a buffer against the strains of everyday life (Hall and Lamont 2009), lower-income people in higher-inequality societies should be less healthy, generating a steeper gradient. Finally, if income inequality is an accurate index of the general level of social inequality in a society (in other words, if income inequality captures social stratification in a very general way), then income inequality should be positively associated with all four measures of health inequality. Thus, our Income Inequality Hypothesis (H2) suggests that nations with higher levels of income inequality will have larger health inequalities.

DATA AND METHOD

Our analysis proceeds in two stages. In the first stage, we assess our first hypothesis – that health gradients exist across social contexts – by estimating health gradients based on education, income, gender and immigration status in a heterogeneous set of societies. In the second stage, we assess our second hypothesis – that health gradients are steeper where income inequality is greater – by estimating the associations between our measures of inequality in health based on income and education and our measures of income inequality at the societal level.

The World Values Survey (WVS) includes a wide range of societies, making it ideal for an exploration of cross-national variation in health inequalities (Hopcroft and Bradely 2007). The original purpose of the WVS was to compare a wide array of societies in terms of general attitudes and values (Inglehart and Baker 2000), but the dataset also offers researchers interested in multiple topics, including health, a unique opportunity to examine cross-national differences. We use data from the fourth (2005) wave of the WVS. Again, the key advantage of the WVS data is that it includes a heterogeneous cross-section of societies that allow us to examine the generality of the health gradient, and to explore one of its possible determinants. In detailing our data and methods below, we highlight our measurement and estimation efforts at ensuring cross-national comparability.

After deleting missing cases, our data are 47,640 observations from 48 WVS countries, representing 74% of the world population, specifically: Australia, Burkina Faso, Bulgaria, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Columbia, Cyprus, Ethiopia, Finland, France, Great Britain, Germany, Ghana, Guatemala, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Italy, Japan, Morocco, Moldova, Mexico, Mali, Malaysia, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Russia, Rwanda, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Taiwan, Ukraine, Uruguay, United States, Vietnam, and Zambia.

Self-assessed health

We use self-assessed health to create our new variables, health gradients based on education, income, gender and immigration status. Survey respondents were asked: “All in all, how would you describe your state of health these days? Would you say it is…” and the response categories were “very good,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” and “very poor.” This measure has been established as a valid indicator of health that predicts mortality and shows strong test-retest reliability (Davies and Ware 1981; Idler and Benyamini 1997; Idler, Hudson, and Levanthal 1999; Lundberg and Manderbacka 1996; Schnittker 2004). Here, we follow a number of other comparative health researchers in employing this measure as an indicator of health status (Eikemo et al. 2007; Espelt et al. 2008; Kunst et al. 2005; Mackenbach et al. 2008; Mansyur et al. 2008; Olafsdottir 2007). In addition, this variable has been recommended as suitable for comparative research by the World Health Organization (de Bruin 1996). Self-assessed health is a partial but valid indicator of health status that has been validated as a predictor of mortality in a number of studies (Idler and Benyamini 1997).

Education and income

To create our four indicators of health inequalities, we first generate societal-level measures of health inequality using individual-level predictors of self-assessed health. The measures of gender and immigration status are created directly from a variable measuring whether the respondent is a woman or a migrant, but making comparable measures of education and income is more challenging. This is both a substantive and methodological issue. Anticipating the measurement details below, we address the comparability of measures in two ways: First, rather than relying on absolute income or education, we transform our measures into relative measures that better capture what it means to have certain levels of education or income within societal context. Second, we use binary logistic regression to estimate measures of health inequalities that are margin-free in that they are unaffected by cross-national differences in the distributions of education and income.

Education is also measured with three relative categories to ensure cross-national comparability (Goesling 2007). We construct the education measure in the same way as the income measure: respondents in the top quartile of the educational attainment distribution are coded as “relative high education,” and respondents in the bottom quartile are coded as “relative low education,” while others are coded as “relative middle education.” The middle category is again the reference category in the regression models.

Income is measured for households, since it more accurately captures available resources than individual income (Lahelma 2001). The original income measure in the WVS is a 10-category ordinal variable, but to enhance the cross-national comparability of income, we rely on relative indicators of affluence and poverty (Bolzendahl and Olafsdottir 2008; Olafsdottir 2007). Specifically, we create three dummy variables and classify respondents as “relative low income” if their income falls into the bottom quartile of the income distribution, as “relatively high income” if it falls into the top quartile of the distribution, and as “relative middle income” if it falls between those extremes. In the models, “relative middle income” serves as the reference category.

Female is an indicator variable, where 1=female and 0=male.

Immigration status is a binary variable where 1=that respondents has a parent that was not born in country and 0=both parents born in country. As this immigration indicator was only available in 37 countries, this variable is not included in the other models.

In addition, we use a limited number of essential control variables for basic demographic characteristics. Age is measured in years, and is expected to have a negative association with the dependent variable. Employment status is an indicator variable, where 1=full time employment and 0=else, and is expected to show a positive association with health. Because the focus of our paper is on social status health inequalities, we do not show the results for the controls in the figures and tables that follow. These results are as expected, and are available from the authors.

Estimation of the health gradients

We use predicted probabilities, generated from binary logistic regression models, to measure health inequalities. For instance, we measure education-based health inequality by calculating the predicted probability of respondents with low relative education reporting “good” or “very good” health, and subtracting that from the predicted probability of respondents with high relative education reporting “good” or “very good” health. This use of predicted probabilities is preferable to reporting differences in logistic regression coefficients because predicted probabilities do not require the assumption that the error variance is identical across countries.

Because income and education are significantly correlated, and because it has been argued that access to higher incomes accounts for part of the education-health association (Mirowsky and Ross 2003), we enter income and education into the model separately (see Mackenbach et al. [2008] for another study that estimates the education and income associations with health separately). Gender inequality in health is also measured as a difference in predicted probability, specifically the predicted probability that women report “good” or “very good” health minus the predicted probability that men report “good” or “very good” health. Unfortunately, the analysis of migrant status is limited to smaller set of WVS countries, due to data availability. In the calculation of predicted probabilities, all covariates other than the focal covariate are held at their means.

Income inequality and health inequalities

Once we have established the size of the health inequalities in each of the 48 nations, we examine the associations between our measures of health inequalities, and a common measure of income inequality: the Gini coefficient. Data come from the UNU-WIDER database. Given the relatively small number of countries in our sample, we show the data in a set of scatterplots. We estimate pair-wise correlations between our contextual covariate and our measures of health inequalities based on income and education. We display scatterplots that show the data, the estimate of the linear fit between health inequality and income inequality, and the 95% confidence interval around the linear fit. Such descriptive analysis is appropriate in this case, since the structural correlates of health inequality have only begun to be assessed. Given the relatively small sample (N = 48) of countries in the WVS, we leave large-N assessments of these findings to future work. Our goal is to provide fresh evidence on the extent of variation in health inequality, and the relationship between health inequalities and income inequality, in as broad a cross-section of societies around the world as possible.

RESULTS

We begin our discussion of the results with our measures of cross-national differences in health inequalities, as estimated using individual-level data on our 48 societies. Then, we turn to our analysis of the relationship between societal-level health inequality and income inequality. We finish by showing our gradients based on gender and immigration status.

A universal gradient?

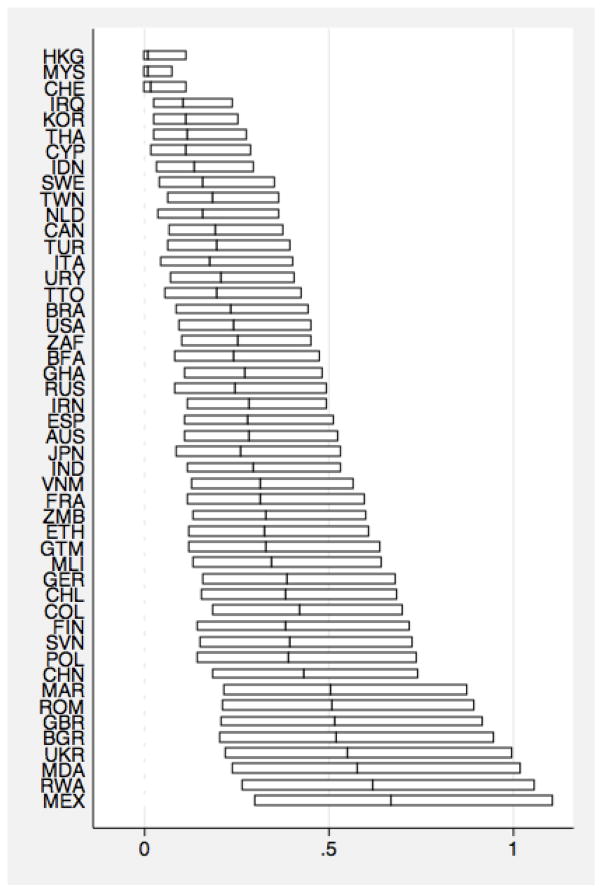

The first step of our analysis is to evaluate whether there is a universal health gradient across our sample of 48 societies. Figure 1 shows large cross-national differences in the extent to which the relatively affluent report better health than relatively poor people. The figure shows, for each country, the difference in the predicted probability of reporting good health for the relatively affluent vs. the relatively poor, along with the 95% confidence interval calculated using the delta method (Xu and Long 2005). Indeed, it shows that there are significant differences in health based on income in all of our countries except three (Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Switzerland). Overall, our results show that relative poverty harms health even in poor countries. Indeed, low income is associated with significantly worse self-reported health in nearly every country (45 out of 48 countries). Yet, importantly, there is substantial variation in the magnitude of the association. The effects of relative poverty or affluence appear to be sensitive to varying social conditions that do not merely reflect economic development, as the largest differences countries as diverse as Great Britain, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Rwanda and Mexico. The Universal Gradient hypothesis is therefore largely supported regarding income.

Figure 1.

Income

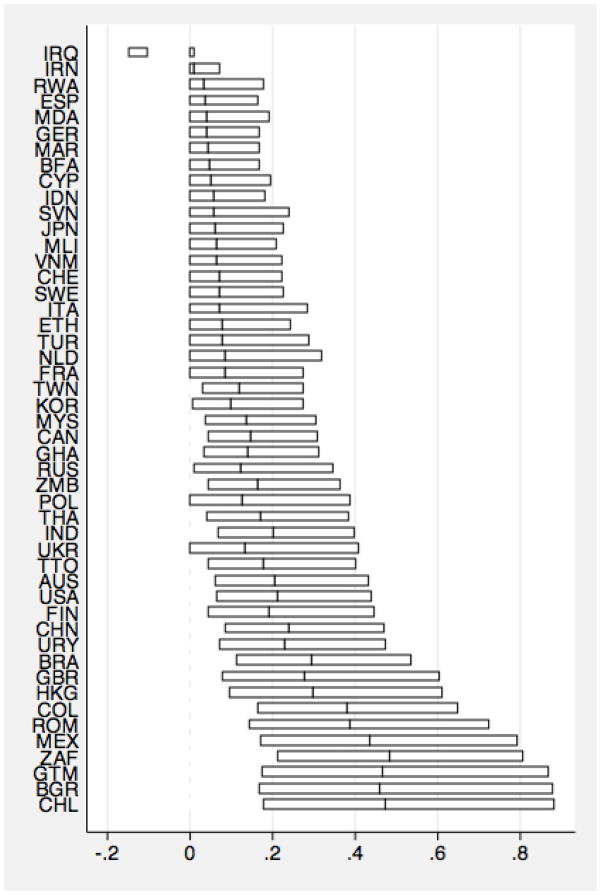

Figure 2 shows a similar relationship for the difference between those with high levels of education and those with low levels of education. In fact, the relationship is significant in all countries but Iraq and the largest health inequalities based on education are in Chile, Bulgaria, Guatemala, and South Africa. Again, we find support for our Universal Gradient Hypothesis.

Figure 2.

Education

Taken together, our results provide reasonably strong support for the universal gradient hypothesis. They show that those who are advantaged in terms of income or education have better health in more than half of our nations, and conversely show that those who are disadvantaged in terms of income and education have worse health. Yet, and perhaps more importantly, the results show that there are important differences across the measures, underscoring the importance of looking at them separately.

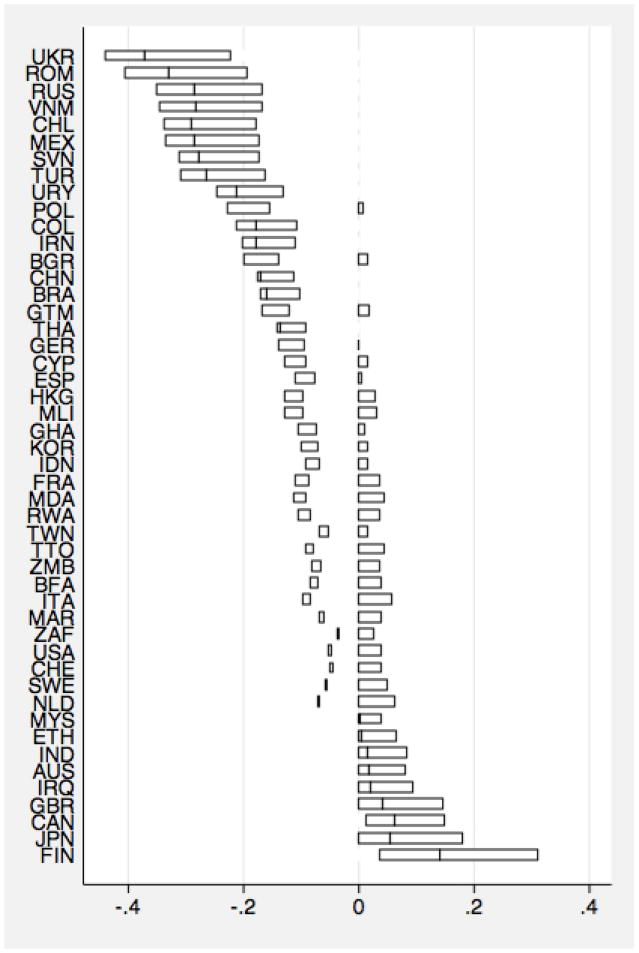

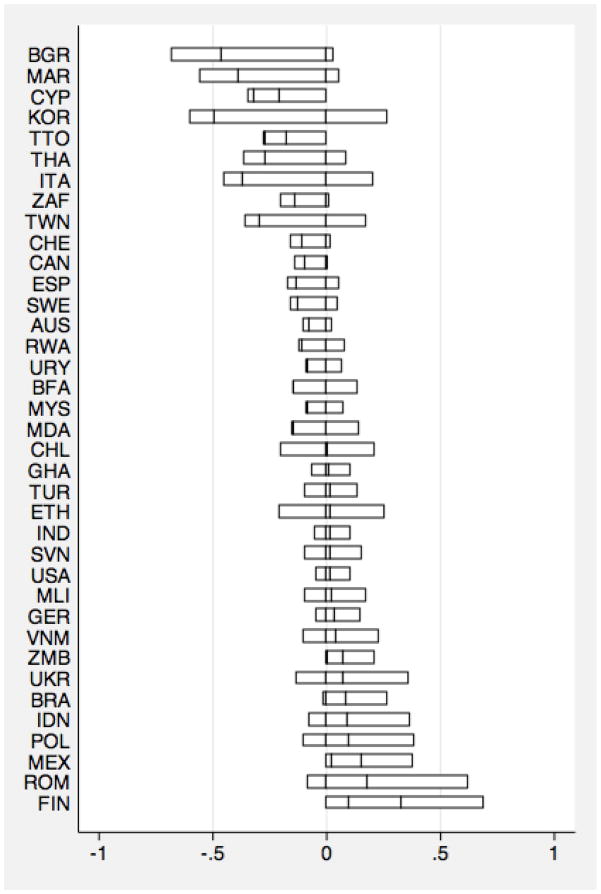

Turning to health inequalities based on gender and immigration status, figures 3 and 4 show a more complex picture. While it appears to be the case that those who are in a vulnerable socioeconomic position across countries experience worse health, the way in which other forms of inequality, in our case gender and immigration status, translate into health inequalities is more mixed. As an example, women experience significantly worse health than men in 9 countries, but significantly better health in 9 countries. Similar patterns are observed for immigration status; immigrants have better health outcomes in some countries but worse in others. These mixed findings underscore the importance of considering what societal characteristics may be related to these types of health inequalities and what it is about the social context that benefits women’s health in some societies, but harms it in others.

Figure 3.

Gender

Figure 4.

Immigration.

Income inequality and the health gradient

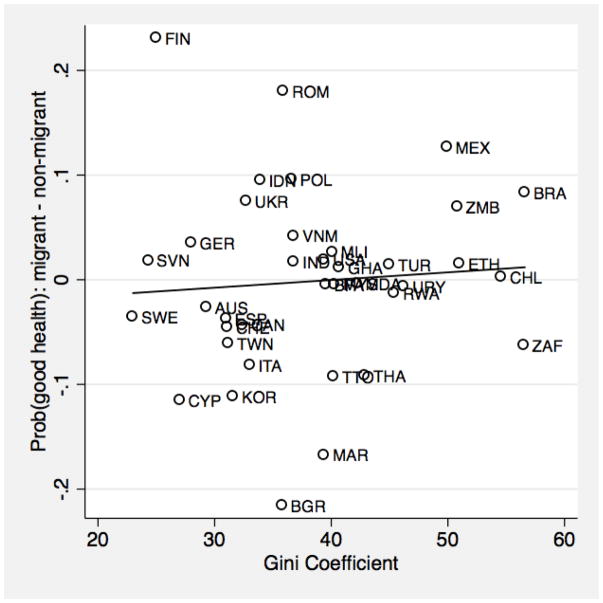

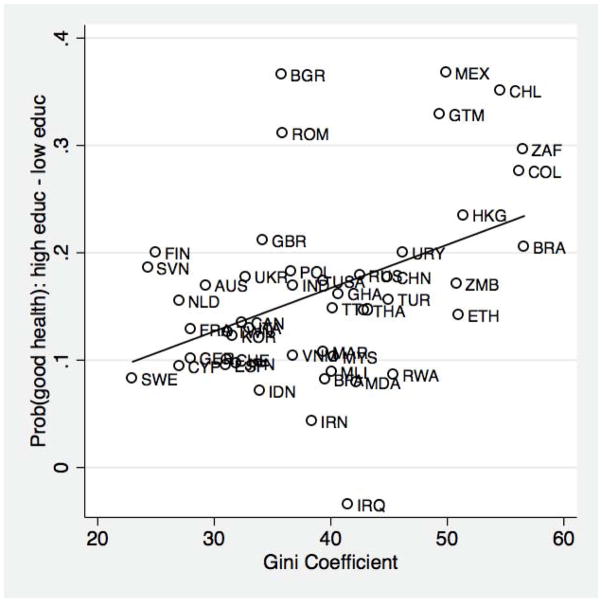

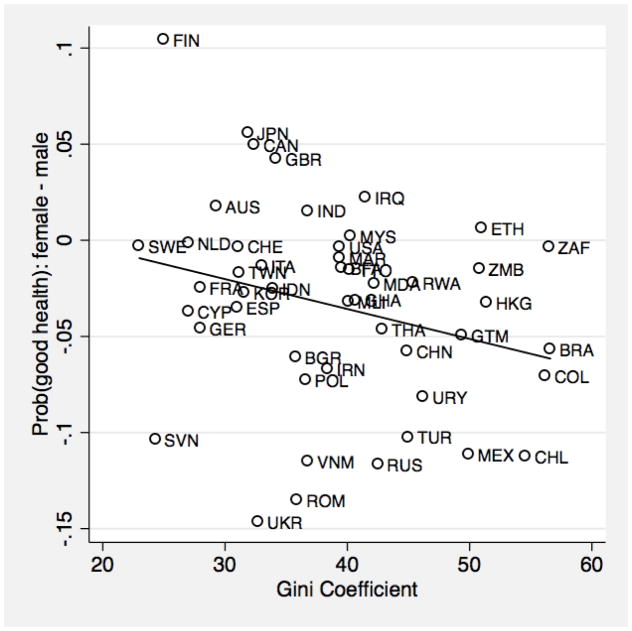

The next step in our analysis is to explore how these variations are conditioned by income inequality in these 48 societies. Our second hypothesis, the Income Inequality Hypothesis, suggests that health inequalities should respond to economic inequality, such that we observe steeper health gradients in societies with higher levels of income inequality. We expect the level of income inequality at the societal level to be more strongly associated with the health inequalities based on income than health inequalities based on the other indicators. The results are displayed in Figures 5 through 8, which show scatterplots and linear regression fits. Figure 5 shows the results for our first income inequality hypothesis: cross-national comparisons of levels of income inequality. Health inequalities based on income have a weak correlation with higher level of income inequality (r =.09). Conversely, figure 6 shows that health inequalities based on education have somewhat of a stronger relationship with the level of income inequality (r =.43). Consequently, our Income Inequality Hypothesis receives at best weak support.

Figure 5.

The relationship between income inequality and health inequalities based on income.

Figure 8.

The relationship between income inequality and health inequalities based on immigration status

Figure 6.

The relationship between income inequality and health inequalities based on education.

Figures 7 and 8 show the relationship between income inequality and gender and migrant status. Figure 7 shows that contrary to expectations, that countries with higher levels of income inequality have less difference in health between men and women. Finally, figure 8 indicates a very weak positive relationship between income inequality and migrant status.

Figure 7.

The relationship between income inequality and health inequalities based on gender.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we conceptualize and investigate inequality in health using a comparative framework. Building on the fundamental-cause perspective, we develop the hypothesis that inequalities in health should manifest in very heterogeneous social contexts. Building on the literature on income inequality and health, we develop the hypothesis that health inequalities should be sensitive to the level of income inequality at the societal level. Both hypotheses are supported by analysis of data from 48 heterogeneous societies represented in the World Values Survey.

One of our central findings is that health inequality generalizes across a very broad range of societies, but takes on diverse patterns in different social contexts. This implies that the fundamental-cause approach to the health gradient can be extended into a comparative framework to understand the variable “social conditions” that generate health gradients. Conceptualizing and measuring health inequality as a cross-national variable opens up a wide range of new research questions that invite new lines inquiry. Much as the cross-national (and historical) variability in income inequality has sparked critical new and multidisciplinary work on the institutional, demographic, and economic determinants of inequality (Alderson and Nielsen 2002; Beckfield 2006; Gottschalk and Smeeding 1997; Guvenen and Kuruscu 2007; Kenworthy 2004; Korpi and Palme 1998; Neckerman and Torche 2007), we believe that research on the determinants of health inequality can generate important new theory- and policy-relevant questions and insights. In this paper, we have taken a step in this direction by showing how much the socioeconomic gradient in health shifts according to varying social conditions. Our results imply that societal-level forces may matter significantly for health inequalities, and suggest the promise of more work investigating the macro-sociological correlates of health inequalities (Hall and Lamont 2009; Putnam and Galea 2008).

Our findings also carry important implications for the debate over the association between income inequality and population health. Rather than focusing exclusively on aggregate measures of average population health such as life expectancy and the infant mortality rate, we argue that progress can be made by investigating the social distribution of population health as a social fact that may respond to cross-national differences in and historical changes in the structure of social inequality. We have taken a step toward that larger goal by showing that education-based health inequalities are larger where income inequality is greater, but much work remains to be done. For instance, using finer-grained measures of health than we have access to here, quantile regression techniques can be used to model health at points across the health distribution other than the mean (see Martins and Pereira [2004] for an application to wages). Also, trends in health inequalities within countries can be modeled using time-series techniques to estimate the impact of changes in income inequality within societies that have experienced particularly pronounced U-turns on income inequality, including the United States and the United Kingdom. Of course, the generality of the association between income inequality and health inequality should also be assessed using an even broader array of societies than we have assembled here.

Such work, in which we are currently engaged, can also help to overcome the limitations of this study, which should of course be noted. The WVS data we use here do not allow for an exploration of longitudinal change in health inequalities (see Krieger et al. [2008] for such an analysis using data from the United States). Nor do the data allow us to analyze potential biological mechanisms (see Avendano et al [2005] for a study of stroke mortality). Also, self-rated health is but one of many measures that can be employed in research on health inequalities (see Kunst and Mackenbach [1994] for alternatives). Moreover, because of the cross-sectional nature of our data we cannot rule out health selection as a potential driver of income- and education-based health inequalities, although we believe it is as interesting to reveal cross-national differences in any health selection effect as it is to show cross-national differences in social inequalities in health.

While country-specific studies of health inequalities have made great strides in documenting and explaining health inequalities, we think such research should be placed in a global context. A global context aids in the evaluation of health inequalities, by providing a comparative scale for how much inequality is “large” or “small.” A global context also identifies health inequalities as subject to social action – institutional variables that are not “natural” but instead systematically vary across societies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mauricio Avendano, Salvatore Babones, Lucy Barnes, Simon Cheng, Nitsan Chorev, Nathan Fosse, Jeremy Freese, Peter Hall, Ichiro Kawachi, Xander Koolman, Nancy Krieger, Peter Marsden, Bernice Pescosolido, Bo Rothstein, Rosemary Taylor, Chris Wildeman, Richard Wilkinson, and seminar participants for comments. We appreciate the research assistance of Maocan Guo. None of these kind scholars bears any responsibility for any errors.

Footnotes

Previous versions of this paper were presented in the Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars Seminar at Harvard University, the Health of Nations Study Group at the Harvard University Center for European Studies, the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, and the International Conference on Inequality, Health and Society, convened at the University of Pittsburgh.

Contributor Information

Jason Beckfield, Harvard University.

Sigrun Olafsdottir, Boston University.

References

- Adler Nancy E, Boyce Thomas, Chesney Margaret A, Cohen Sheldon, Folkman Susan, Kahn Robert L, Leonard Syme S. Socioeconomic Status and Health: The Challenge of the Gradient. American Psychologist. 1994;49:15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderson Arthur S, Nielsen Francois. Globalization and the Great U-Turn: Income Inequality Trends in 16 OECD Countries. American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107:1244–99. [Google Scholar]

- Avendano Mauricio, Kunst AE, Van Lenthe F, Bos V, Costa G, Valkonen T, Cardano M, Hardings S, Borgan JK, Glickman M, Reid A, Mackenbach JP. Trends in Socioeconomic Disparities in Stroke Mortality in Six European Countries between 1981–1985 and 1991–1995. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;161:52–61. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babones Salvatore. Income Inequality and Population Health: Correlation and Causality. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66:1614–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckfield Jason. Does Income Inequality Harm Health? New Cross-National Evidence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45:231–248. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckfield Jason. European Integration and Income Inequality. American Sociological Review. 2006;71:961–85. [Google Scholar]

- Beckfield Jason, Krieger Nancy. Epi + demos + cracy: A Critical Review of Empirical Research Linking Political Systems and Priorities to the Magnitude of Health Inequities. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2009 doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp002. (forthcoming) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolzendahl Catherine, Olafsdottir Sigrun. Gender Group Interest or Gender Ideology? Comparing Americans’ Support of Family Policy within the Liberal Welfare Regime. Sociological Perspectives. 2008;51:281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Brady David, Kaya Yunus, Beckfield Jason. Reassessing the Effect of Economic Growth on Well-Being in Less Developed Countries, 1980–2003. Studies in Comparative and International Development. 2007;42:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler David, Deaton Angus, Lleras-Muney Adriana. The Determinants of Mortality. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20:97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Davey Smith George, Bartley Mel, Blane David. The Black Report on Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health 10 Years on. British Medical Journal. 1990;301:373–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6748.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies Allyson Ross, Ware John E. Measuring Health Perceptions in the Health Insurance Experiment. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin A, Pichavet HSJ, Nossikov Anatoly. Health Interview Surveys: Towards International Harmonization of Methods and Instruments. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Publications; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger Klaus, Squire Lyn. A New Data Set Measuring Income Inequality. World Bank Economic Review. 1996;10:565–91. [Google Scholar]

- Eikemo Terje A, Huisman Martijn, Bambra Clare, Kunst Anton E. Health Inequalities According to Educational Level in Different Welfare Regimes: A Comparison of 23 European Countries. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2008;30:565–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelt Albert, Borrell Carme, Rodriguez-Sanz Maica, Muntaner Carles, Isabel Pasarin M, Benach Joan, Schaap Maartje, Kunst Anton E, Navarro Vicente. Inequalities in Health by Social Class Dimensions in European Countries of Different Political Traditions. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;2008:1–11. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans William N, Hout Michael, Mayer Susan E. Assessing the Effect of Economic Inequality. In: Neckerman Kathryn., editor. Social Inequality. New York: Russell Sage; 2004. pp. 933–68. [Google Scholar]

- Goesling Brian. The Rising Significance of Education for Health? Social Forces. 2007;85:1621–44. [Google Scholar]

- Goesling Brian, Firebaugh Glenn. The Trend in International Health Inequality. Population and Development Review. 2004;30:131–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk Peter, Smeeding Timothy M. Cross-National Comparisons of Earnings and Income Inequality. Journal of Economic Literature. 1997;35:633–687. [Google Scholar]

- Graham Hilary. Unequal Lives: Health and Socioeconomic Inequalities. New York: Open University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guvenen Fatih, Kuruscu Burhanettin. A Quantitative Analysis of the Evolution of the U.S. Wage Distribution: 1970–2000. NBER Working Paper. 2007:13095. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Peter A, Lamont Michele., editors. Successful Societies: How Institutions and Cultural Frameworks Affect Health and Capabilities. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hopcroft Rosemary L, Bradley Dana Burr. The Sex Difference in Depression in 29 Countries. Social Forces. 2007;85:1483–1508. [Google Scholar]

- House James S. Understanding Social Factors and Inequalities in Health: 20th Century Progress and 21st Century Prospects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:125–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House James S, Lantz Paula M, Herd Pamela. Continuity and Change in the Social Stratification of Aging and Health over the Life Course: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Longitudinal Study from 1986 to 2001/2002 (Americans’ Changing Lives Study) Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:S15–S26. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hout Michael, Fischer Claude S. Working paper. University of California-Berkeley; 2003. Money and Morale. [Google Scholar]

- Idler Ellen L, Benyamini Yael. Self-Rated Health and Mortality: A Review of Twenty-Seven Community Studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler Ellen L, Hudson Shawna V, Leventhal Howard. The Meanings of Self-Ratings of Health: A Qualitative and Quantitative Approach. Research on Aging. 1999;21:458–76. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart Ronald, Baker Wayne E. Modernization, Cultural Change, and the Persistence of Traditional Values. American Sociological Review. 2000;65:19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jen Min Hua, Jones Kelvyn, Johnston Ron. Global Variations in Health: Evaluating Wilkinson’s Income Inequality Hypothesis Using the World Values Survey. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:643–53. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy Lane. Egalitarian Capitalism: Jobs, Incomes, and Growth in Affluent Countries. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Daniel, Kawachi Ichiro, Hoorn Stephen Vander, Ezzati Majid. Is Inequality at the Heart of It? Cross-Country Associations of Income Inequality with Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:1719–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston Paul W, Hubbard Ryan, Lapp Brent, Schroeder Paul, Wilson Julia. Why Education Matters. Sociology of Education. 2003;76:53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa Evelyn M, Hauser Philip M. Differential Mortality in the United States: A Study of Socioeconomic Epidemiology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Korpi Walter, Palme Joakim. The Paradox of Redistribution and Strategies of Equality: Welfare State Institutions, Inequality, and Poverty in the Western Countries. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:661–687. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger Nancy, Rehkopf DH, Chen Jarvis T, Waterman Pamela D, Marcelli E, Kennedy M. The Fall and Rise of US Inequities in Premature Mortality: 1960–2002. Plos Medicine. 2008;5:227–41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunitz Stephen J. The Health of Populations: General Theories and Particular Realities. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kunitz Stephen J, Pesis-Katz Irena. Mortality of White Americans, African Americans, and Canadians: The Causes and Consequences for Health of Welfare State Institutions and Policies. The Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83:5–39. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2005.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst Anton E, Mackenbach Johan P. Measuring Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kunst Anton E, Bos Vivian, Lahelma Eero, Bartley Mel, Lissau Inge, Regidor Enrique, Mielck Andreas, Cardano Mario, Dalstra Jetty AA, Geurts Jose JM, Helmert Uwe, Lennartsson Carin, Ramm Jorun, Spadea Teresa, Stronegger Willibald J, Mackenbach Johan P. Trends in Socioeconomic Inequalities in Self-Assessed Health in 10 European Countries. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;34:295–305. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahelma Eero. Health and Social Stratification. In: Cockerham WC, editor. The Blackwell Companion to Medical Sociology. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers Inc; 2001. pp. 64–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lahelma Eero, Rahkonen Ossi, Huuhka Minna. Changes in the Social Patterning of Health? The case of Finland 1986–1994. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44:789–99. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link Bruce G, Phelan Jo. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;(extra issue):80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J Scott. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg Olle, Manderbacka K. Assessing Reliability of a Measure of Self-Rated Health. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine. 1996;24:218–224. doi: 10.1177/140349489602400314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfey Karen, Freese Jeremy. Toward some Fundamentals of Fundamental Causality: Socioeconomic Status and Health in the Routine Clinic Visit for Diabetes. American Journal of Sociology. 2005;110:1326–1372. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch Scott M. Explaining Life Course and Cohort Variation in the Relationship Between Education and Health: The Role of Income. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:324–338. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre Sally. The Black Report and Beyond: What are the Issues? Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44:723–45. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach Johan P, Stirbu Irina, Roskam Albert-Jan R, Schaap Maartje M, Menvielle Gwenn, Leinsalu Mall, Kunst Anton E. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health in 22 European Countries. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:2468–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansyur Carol, Amick Benjamin C, Harrist Ronald B, Franzini Luisa. Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Self-Rated Health in 45 Countries. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot Michael. Social Determinants of Health Inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins Pedro S, Perira Pedro T. Does Education Reduce Wage Inequality? Quantile Regression Evidence from 16 Countries. Labour Economics. 2004;11:355–71. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown Thomas. The Role of Medicine: Dream, Mirage, or Nemesis? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Education, Social Status and Health. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E, Reynolds John. Links between Social Status and Health. In: Bird CE, Conrad P, Fremont AM, editors. Handbook of Medical Sociology, fifth edition. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall; 2000. pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Vicente. Medicine under Capitalism. New York: Prodist; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Neckerman Kathryn., editor. Social Inequality. New York: Russell Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Neckerman Kathryn, Torche Florencia. Inequality: Causes and Consequences. Annual Review of Sociology. 2007;33:335–57. [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir Sigrun. Fundamental Causes of Health Disparities: Stratification, the Welfare State, and Health in the United States and Iceland. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:239–53. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir Sigrun, Beckfield Jason. Health and the Social Rights of Citizenship: Integrating Welfare State Theory and Medical Sociology. In: Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, McLeod JD, Rogers A, editors. Handbook of Sociology of Health, Illness, and Healing. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan Jo C, Link Bruce G. Controlling Disease and Creating Disparities: A Fundamental Cause Perspective. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:S27–33. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam Sara, Galea Sandro. Epidemiology and the Macrosocial Determinants of Health. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2008;29:275–89. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Stephanie A, House James S. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health: An Enduring Sociological Problem. In: Bird CE, Conrad P, Fremont AM, editors. Handbook of Medical Sociology. 5. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall; 2000. pp. 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E, Mirowsky John. Does Employment Affect Health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:230–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E, Wu Chia-ling. The Links Between Education and Health. American Sociological Review. 1995;60:719–745. [Google Scholar]

- Ross Catherine E, Wu Chia-Ling. Education, Age, and the Cumulative Advantage in Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:104–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker Jason. Education and the Changing Shape of the Income Gradient in Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45:286–305. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker Jason, McLeod Jane D. The Social Psychology of Health Disparities. Annual Review of Sociology. 2005;31:75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Starfield Barbara. State of the Art in Research on Equity in Health. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2006;31:11–32. doi: 10.1215/03616878-31-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend Peter, Davidson Nick. Inequalities in Health: The Black Report. London: Penguin; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Valkonen Tapani. Adult Mortality and Level of Education: A Comparison of Six Countries. In: Fox AJ, editor. Health Inequalities in European Countries. Aldershot: Gower; 1989. pp. 142–60. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorslaer Eddy, Koolman Xander. Explaining the Differences in Income-Related Health Inequalities across European Countries. Health Economics. 2004;13:609–28. doi: 10.1002/hec.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren John Robert. Job Characteristics as Mediators in SES-Health Relationships. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59:1367–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber Max. Class, Status, Party. In: Gerth HH, Wright Mills C, editors. From Max Weber. New York: Oxford University Press; 1904. pp. 180–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson Richard. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. London: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson Richard G, Pickett Kate E. Income Inequality and Population Health: A Review and Explanation of the Evidence. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:1768–84. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R. Socioeconomic Differentials in Health: A Review and Redirection. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1990;53:81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R, Collins Chiquita. US Socioeconomic and Racial Differences in Health: Patterns and Explanations. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995;21:349–386. [Google Scholar]

- Winship Chris, Mare Robert D. Regression Models with Ordinal Variables. American Sociological Review. 1984;49:512–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge Jeffrey M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Mason, Ohio: Thomson; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Yang. Trends in U.S. Adult Chronic Disease Mortality: Age, Period, and Cohort Variations. Demography. 2008;45:387–416. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman Frederick J. A Commentary on ‘Neo-Materialist Theory and the Temporal Relationship between Income Inequality and Longevity Change. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66:1882–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]