Abstract

Understanding the development and dysfunction of the human brain is a major goal of neurobiology. Much of our current understanding of human brain development has been derived from the examination of post-mortem and pathological specimens, bolstered by observations of developing non-human primates and experimental studies focused largely on mouse models. However, these tissue specimens and model systems cannot fully capture the unique and dynamic features of human brain development. Recent advances in stem cell technologies that enable the generation of human brain organoids from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) promise to profoundly change our understanding of the development of the human brain and enable a detailed study of the pathogenesis of inherited and acquired brain diseases.

The ability to reprogramme human somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and then direct those cells towards a specific cell fate has begun to revolutionize the study of human embryo and organ development and disease1. Major advances in our understanding of developmental programmes and the improvement of in vitro protocols for the differentiation of PSCs (which include iPSCs and embryonic stem cells (ESCs)) have culminated in the generation of ‘organoid technologies’. Organoids are in vitro-derived structures that undergo some level of self-organization and resemble, at least in part, in vivo organs. For brain-like organoids derived using current protocols, the resemblance is limited, which is not surprising given the complexity of the human brain. Nevertheless, several key features of in vivo brain organogenesis are recapitulated by in vitro organoids, making them attractive models for studies of certain aspects of brain development.

Organoid generation relies on the remarkable ability of stem and progenitor cells to self-organize to form complex tissue structures. These structures can contain areas resembling diverse regions of the brain, in which case they are often referred to as ‘brain organoids’ or ‘cerebral organoids’, reflecting the presence of broad regional identities2. Alternatively, they may contain structures that resemble specific brain regions and thus can be referred to as organoids of that region, such as ‘forebrain organoids’ or ‘midbrain organoids’ (REFS 3–5). In this Review, we will use the term brain organoid in reference to the general field and employ the terms used by authors when referring to their specific studies.

To date, a variety of protocols for organoid generation have been published, many of which aim to model cortical development2,3,5,6. However, protocols have also been published for the generation of organoids that model the development of other human brain regions, including the hippocampus7, midbrain4,5,8, hypothalamus5, cerebellum5,9, anterior pituitary10 and retina10,11. In this article, we highlight recent advances in the field and discuss how they have enabled modelling of human disease and neurodevelopmental disorders. We discuss the limitations of existing models and consider what can be done to further improve this promising technology.

Generating organoids

Brain organoid technologies derive from earlier work on the culture of embryoid bodies. Embryoid bodies are large multicellular aggregates of PSCs that are often generated as an early step in stem cell differentiation protocols and are capable of undergoing developmental specification similar to that of the pregastrulation embryo12. In 2001, ESCs were used to generate embryoid bodies that could be directed towards a neural lineage13. When plated on coated dishes, the embryoid bodies generated clusters of neuroepithelial cells that self-organized in 2D culture to form rosettes. The rosette formations displayed features of the embryonic neural tube, including a pseudostratified epithelium with apico-basal polarity that recapitulated the properties of neuroepithelial cells and radial glial cells, the stem cells of the developing brain14,15. It was later shown that ESCs were able to produce neural precursors in the absence of serum, growth factors, or other inductive signals16, demonstrating the remarkable ability of PSCs to spontaneously acquire neural identity. It was also demonstrated that cell aggregation was not essential for efficient neural differentiation16, and a number of protocols for generating cortical neurons from monolayer cultures were developed17,18.

The development and formation of apico-basally polarized tissue from PSCs was extensively described by Yoshiki Sasai and colleagues in a number of seminal papers that used serum-free suspension culture of embryoid bodies and the addition of specific inductive signals to generate forebrain neural precursors19. In 2011, a 3D neural culture system using human ESCs was used to generate self-organizing optic cup-like structures displaying features of retinal architecture20. Building on these findings, and following advances in organoid technologies in which a supportive extracellular matrix (Matrigel) was used to support tissue growth21, two further advances helped to pioneer the field of brain organoids. First, an in vitro system for the generation of brain-like organoids was developed2. These 3D structures contained regions that resembled various discrete brain regions and were thus called cerebral organoids. Strikingly, they contained cortical-like regions that displayed an organization similar to that of the early developing human cortex. Second, a subsequent study used inductive signalling molecules to mimic endogenous patterning and drive effective dorsal and ventral fore-brain differentiation3. Both of these protocols generated organoids containing a dorsalized neuroepithelium that reproduced certain aspects of cortical development, both structurally and in terms of cell behaviour. The proliferative ventricular-like zones contained neural stem cells that, over time, produced a multilayered cortical-like structure that included a marginal-like zone containing Reelin-positive Cajal–Retzius cells, a subplate-like region, and a cortical plate-like zone containing cells expressing markers of deep- and superficial-layer neurons. Importantly, these organoids displayed features of human development that are not found in the mouse, such as the presence of outer radial glial cells (oRGs, also known as basal radial glial cells) in a subventricular- like zone22,23 (FIG. 1). Thus, human brain organoids could produce human-relevant cell types (as had been shown earlier in 2D PSC-derived cell cultures24), spurring an intense interest in organoid technologies as a model system to study human-specific features of brain development.

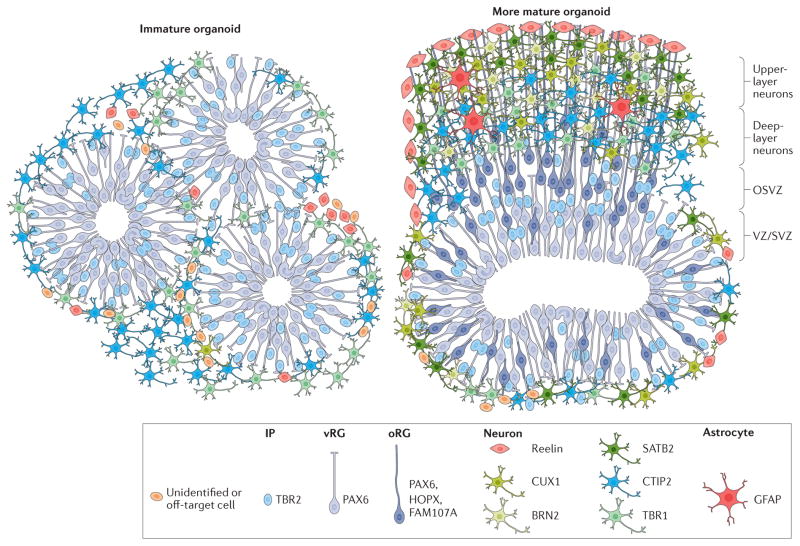

Figure 1. Cortical organoids generated with current protocols.

Schematic representation of cortical organoids generated with current protocols. Immunohistochemical analyses reveal rosette-like structures in immature organoids (left). These contain neuroepithelial stem cells and ventricular radial glial cells (vRGs) that divide at the apical surface and form a ventricular-like zone (VZ). Intermediate progenitors (IPs) and neurons surround the VZ. Cells that express markers of early cortical plate neurons such as COUP-TF-interacting protein 2 (CTIP2, also known as BCL11B) and T-box brain protein 1 (TBR1) are also generated in immature organoids2,3,5. More mature organoids (right) display multiple progenitor zones, including a VZ and a subventricular-like zone (SVZ). Immunohistochemistry reveals the presence of outer radial glial cells (oRGs), forming the outer subventricular zone (OSVZ) and the presence of cells expressing specific cortical layer markers and glial cell markers5. The molecular markers of cell identity demonstrated in this schematic are based on findings from REF 5. BRN2, POU domain, class 3, transcription factor 2; CUX1, homeobox protein cut-like 1; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; HOPX, homeodomain-only protein; PAX6, paired box protein Pax-6.

Over the past few years, a variety of brain organoid protocols have been developed, many of which focus on modelling cortical development2,3,5,25–27 (BOX 1; TABLE 1). A major subject of discussion regarding these protocols is the extent to which self-organization is favoured over cell fate induction achieved through the addition of extrinsic signalling molecules. Some protocols build on the principles of spontaneous neural induction by using medium that is free of neural induction signalling molecules2,27. This promotes the generation of diverse brain regions and cell populations2,28,29. Although such regional diversity is appealing, it also leads to a relatively variable outcome and the differentiation of some cells into non-ectodermal cell types28,29. Most protocols therefore optimize neural induction by mimicking endogenous patterning through the application of exogenous cues (TABLE 1). Commonly, neural induction in brain organoids includes inhibition of SMAD signalling to inhibit mesoderm and endoderm formation, followed by the provision of specific morphogens and fate-specifying molecules18. A better understanding of the spatial and temporal aspects of morphogen signalling in organoid generation will therefore enable researchers to better mimic in vivo developmental programmes.

Box 1. Generation and characterization of cerebral organoids.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can be derived via the reprogramming of somatic cells (see the figure). In this process, a mature cell is converted back into a pluripotent stem cell, through the introduction of ‘reprogramming factors’. Following reprogramming, patient iPSCs bearing disease-causing mutations can be genetically ‘repaired’, or mutations can be introduced into wild-type iPSCs to create isogenic cell lines. The 3D aggregation of pluripotent stem cells (including both iPSCs and embryonic stem cells (ESCs)) in the presence of neural induction molecules drives the formation of neural rosette structures (FIG. 1). These structures can largely self-organize under optimal conditions to give rise to more complex structures termed cerebral organoids. A variety of bioengineering techniques, including scaffolds and bioreactors, have enabled improvements in organoid viability and maturation. Single-cell transcriptome profiling can be used to compare organoids to the developing human brain to evaluate the fidelity of organoid models, and electrophysiological and morphological analyses can be used to profile cells. Despite these advances, a detailed and multidimensional analysis of cell types and cell type maturation is needed to improve protocols and establish more robust models.

Table 1.

Protocols for brain organoid generation

| Organoid identity | Starting material | Intrinsic patterning or extrinsic signalling molecules | Extracellular scaffold and/or bioreactor | Special considerations for cortical modelling | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optic cup-retinal | ESCs | Intrinsic | Matrigel | NA | 20 |

| Adenohypophysis | ESCs | Smoothened agonist (SAG) and additional, cell-type-specific, molecules | None | NA | 10 |

| Whole brain | ESCs and/or iPSCs | Intrinsic | Matrigel and a spinning bioreactor | First protocol describing whole-brain organoid generation | 2 |

| iPSCs | Intrinsic | Chemically defined hydrogel | NA | 27 | |

| iPSCs | Intrinsic | Matrigel and a spinning bioreactor |

|

28 | |

| Forebrain | ESCs | SB-431542 (TGFβ, Activin and NODAL inhibitor) and IWR1 (WNT inhibitor) | Matrigel | Detailed description of forebrain organoids with use of small molecules | 3 |

| iPSCs | Dorsomorphin (BMP inhibitor), A83 (BMP and TGFβ inhibitor), SB-431542, WNT3A, CHIR99021 (GSK3β inhibitor), BDNF and GDNF | Matrigel and a mini bioreactor |

|

5 | |

| Ventral forebrain | ESC | SB-431542, IWR1 and SAG | Matrigel | Directed differentiation of ventral forebrain structures. | 3 |

| Cerebellum | ESCs | SB-431542, FGF2, FGF19 and SDF1 | None | NA | 9 |

| Cortex | iPSCs | Dorsomorphin, SB-431542, FGF2 EGF, BDNF and NT3 | None | Extensive astrogenesis reported | 25 |

| Dorsal cortex | iPSCs and/or ESCs | Intrinsic or CycA (SHH signalling antagonist) | Matrigel and a spinning bioreactor | None | 26 |

| Ventral cortex | iPSCs and/or ESC | IWP2 (WNT inhibitor) and SAG | Matrigel and a spinning bioreactor | Generation of diverse interneuron subtypes | 26 |

| Hippocampus and choroid plexus | ESCs | WNT inhibitor, SB-431542, GSK3 inhibitor and BMP4 | None | NA | 7 |

| Midbrain | iPSCs | LDN-193189 (BMP and SMAD inhibitor), SB-431542, SHH, FGF8, purmorphamine (Smoothened agonist), GSK3β inhibitor, BDNF and GDNF | Matrigel and a mini bioreactor | NA | 5 |

| ESCs | SB-431542, Noggin, CHIR99021, SHH, FGF8, BDNF, GDNF and a cAMP pathway activator | Matrigel and a shaker | NA | 4 | |

| NESCs | SB-431542, dorsomorphin, CHIR99021, purmorphamine, BDNF, GDNF, a cAMP pathway activator and TGFβ3 | Matrigel and a shaker | NA | 8 | |

| Hypothalamus | iPSCs | LDN-193189 SB-431542, WNT3A, SHH, SAG, FGF2 and CNTF | Matrigel and a mini bioreactor | NA | 5 |

| Pallium | iPSCs and/or ESCs | Dorsomorphin, SB-431542, EGF, FGF2, BDNF and NT3 | None | Targeted differentiation for reproducible organoid generation. No off-target mesoderm differentiation | 6 |

| Subpallium | iPSCs and/or ESCs | Dorsomorphin, SB-431542, EGF, FGF, BDNF, NT3, WP2 (WNT inhibitor), SAG and allopregnanolone | None | Generation of diverse interneuron subtypes. Report of small OPC production | 6 |

BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; CNTF, ciliary neurotrophic factor; EGF, epidermal growth factor; ESCs, embryonic stem cells; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor 2; GDNF, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; NA, not applicable; NESCs, neuroepithelial stem cells; NT3, neurotrophin 3; OPC, oligodendrocyte progenitor cell; oRG, outer radial glial cell; OSVZ, outer subventricular zone; SDF1, stromal cell-derived factor 1; SHH, sonic hedgehog; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β.

Correctly mimicking morphogen signalling in in vitro cultures is difficult due to the complex interplay of regional and temporal expression in vivo. For example, in embryogenesis, the effects of WNT signalling are stage specific, and there are divergent roles for WNT signalling in cell proliferation and cell type specification that depend on its temporal and regional expression (for reviews, see REFS 30,31). In vivo, WNT signalling is known to play an important role in body axis determination and cell fate patterning32. Before gastrulation, WNT signalling is implicated in establishing the dorsoventral body axis, and its targets include genes that are essential for dorsal mesoderm formation32. Following gastrulation, the WNT pathway is important for antero-posterior axis specification31,32. Several WNT ligands are expressed in the posterior region of the embryo, whereas multiple WNT antagonists are expressed in the anterior (head) region31,32. Mouse studies have also suggested that, following forebrain specification (the establishment of the anteroposterior axis), WNT signalling plays a role in the dorsoventral patterning of the forebrain by repressing the molecular identity of ventral forebrain progenitors33.

Similar to its in vivo patterning, inhibition of WNT signalling promotes anterior identity and enhances neurectodermal differentiation during early-stage embryoid body differentiation, whereas activation of WNT signalling posteriorizes the embryoid body and promotes mesoderm differentiation34. Additionally, it has been shown that when canonical WNT signalling is activated in PSCs during neural differentiation, neural progenitors of a caudal identity are induced in a dose-dependent manner, mimicking in vivo patterning35. Reflecting this, in order to promote the induction of forebrain fate, some organoid protocols use WNT inhibition to block the caudalizing effects of WNT19,36.

In embryogenesis, WNT signalling in the forebrain may also have a mitogenic role: constitutively active Wnt signalling leads to an enlarged forebrain primordium in the mouse, owing to an expansion of the progenitor cell population37. Activation of WNT signalling from embryonic day (E) 10.5 in mice also inhibits cortical neural differentiation, whereas its inactivation promotes terminal differentiation38. These results suggest a role for WNT signalling in promoting symmetric proliferative divisions during early cortical development and expanding the progenitor cell population, indicating that activation of WNT signalling could be used to expand the neuroepithelial-like regions of organoids. WNT3A or a WNT pathway activator has therefore been used in combination with SMAD inhibition at early stages of forebrain organoid protocols, where it was found to promote production of neuroepithelial-like organoids and significantly reduce cell death5.

In organoid generation, the pattern of signalling by WNT and other growth factors has not yet been fully examined. Given that the activity of signalling factors in vivo is regulated in a strict temporal and spatial pattern, future protocols will benefit from strategies by which the regional and temporal activity of morphogen signalling seen in vivo is more faithfully recapitulated.

Apart from growth factor cues, other modulators — such as scaffold support provided by the extracellular matrix — are important features of current protocols2,5,28. Some methods use scaffold-free conditions that, when combined with extrinsic neural induction, produce cortical spheroids that undergo both neurogenesis and astrogliogenesis, thus reproducing another important aspect of the cellular diversity of cortical development25. Bioreactors designed to improve oxygen diffusion and nutrient distribution have been used to produce larger and more viable structures that can grow for longer periods2,5 (BOX 1). The technology is evolving rapidly, and one can anticipate significant advances in the near future that will result in more consistent, mature, and architectonically complex cerebral organoids.

Organoids as models of development

The organoid field, although promising, remains young, and there is much room for improvement before it will be a truly robust model for developmental studies. One important issue is that organoids derived from the same cell line under the same conditions can often produce tissues with different regional identities and spatial and cellular heterogeneity28,29. This is especially evident in organoids undergoing self-assembly with minimal addition of extrinsic factors. Moreover, the extent to which organoids faithfully recapitulate in vivo human development is only beginning to be understood.

Recapitulating aspects of human neurodevelopment

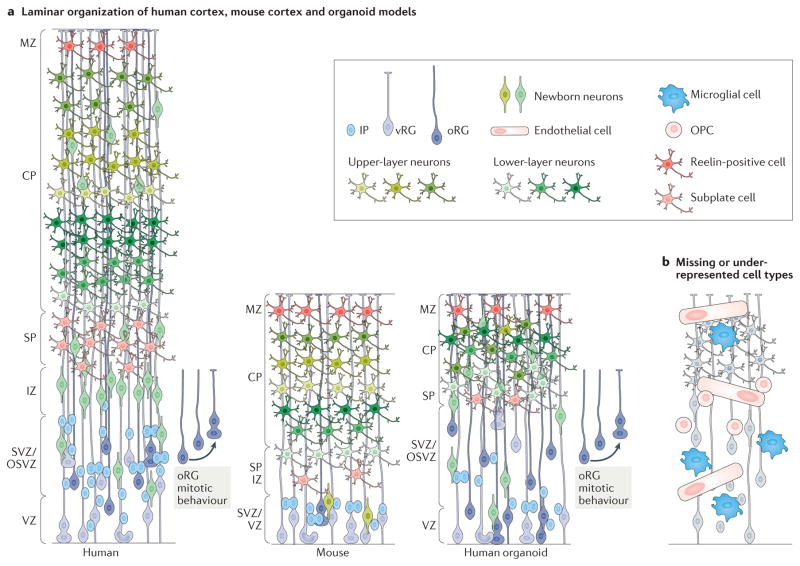

The production of radial glial cells, intermediate progenitors, and deep- and superficial-layer neurons in an ordered temporal fashion has been reported by studies using all of the protocols currently in use2,3,5,25. A recent study further demonstrated the production of cortical neuron subtypes expressing markers found in all six cortical layers5 (FIG. 1). Remarkably, these distinct subclasses of neuronal cells exhibited multilaminar organization, although they did not form the six distinct layers seen in normal mammalian cortex (FIG. 2a). Interestingly, the developmental timing of cortical neurogenesis appears to be conserved in vitro and has been demonstrated with both suspension and adherent differentiation methods2,3,5,39.

Figure 2. Human cerebral organoids as models of cortical development.

a | Schematics illustrating the cellular composition and laminar organization of the developing human and mouse cortex45 and that of a typical human organoid (not to scale)2,3,5. Human cortex and human organoid models notably share an expanded subventricular zone (SVZ) that contains an outer SVZ (OSVZ)22,45. Human organoid models therefore provide an important advance in our ability to study the role of the expanded human SVZ and the cell types associated with this region in vitro. Outer radial glial cells (oRGs), characteristic of the human SVZ, have been identified in organoids2,3,5,25,50. Over time, cortical organoids are able to generate diverse neuronal subtypes that can become organized into deep and upper layers as has been shown by immunohistochemistry2,3,5,25. However, current models do not display the complexity or organization of mouse or human laminar organization. b | Current organoid protocols do not produce all the cell types known to be important for human cortical development. The schematic illustrates some of the cell types under-represented in current organoid models. Importantly, cerebral organoids lack vascularization (endothelial cells) and microglial cells. Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) are also uncommon in most protocols. CP, cortical plate; IP, intermediate progenitor cell; IZ, intermediate zone; MZ, marginal zone; SP, subplate; vRG, ventricular radial glial cell.

Another important aspect of human development that has been reported in brain organoids is the generation of an outer subventricular zone (OSVZ) containing an abundant population of oRG progenitor cells. oRGs are present in large numbers in gyrencephalic primates22,23,40–44 and are considered pivotal to the evolutionary increase in human cortex size and complexity45,46. The oRG population is largely missing in mouse brain development47, and human cellular models therefore provide a unique opportunity to study this cell population. oRGs were first suggested to be present in human organoid models due to the detection of proliferating cells expressing radial glial markers located away from the ventricular-like zone2,3. However, due to the general disorganization of organoid tissue, the anatomical location of cells can be a poor indicator of cell identity. It was only after the molecular identity of oRGs was established48 that an OSVZ-like zone containing oRGs could be reliably identified based on marker expression5 (FIG. 1). Time-lapse confocal microscopy of organoid cells displaying the characteristic mitotic behaviour of oRGs provided further evidence of their identity49,50, and single-cell transcriptome sequencing has been used to confirm the presence of cells with oRG gene expression signatures50.

Human brain organoids are therefore potentially useful for modelling human-specific traits, such as the cell types and structural features of the human brain, or the effects of disease-causing mutations that are difficult to model in the mouse. For example, the mechanisms underlying human cortical expansion and gyrification could be investigated with organoids. A recent report described expansion and surface folding of cerebral organoids following phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) deletion and enhancement of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)–AKT growth signalling pathway51, suggesting that increased neural progenitor proliferation may be a major contributing factor to expansion and gyrification of the human brain. However, folding in the organoids was prominent in the neuroepithelium, and the relationship of this folding phenotype to actual cortical folding (which develops largely after neurogenesis ends and involves the cortical mantle rather than the proliferative zone) remains unclear.

Cell type diversity and reproducibility

In-depth studies of the cell types produced in brain organoids and how they compare to their in vivo counterparts are needed in order to assess their validity as developmental models. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has been used to compare gene expression in cerebral organoids to bulk or microdissected regions of human fetal brain. The results show that the transcriptional profiles of organoids cultured for up to 100 days are similar to those of developing human cortex at post-conceptional weeks 17–24 (REFS 25,29). Interestingly, the transcriptomic profiles of organoid-derived neurons show greater neuronal maturation than those of 2D monolayer-derived neurons25. However, it is important to note that cell composition differences may drive gene expression signals in these comparisons: thus, ‘maturation’ may reflect the relative proportions of differentiated neurons and progenitors, which changes over developmental time.

To overcome this problem, recent studies have begun to profile gene expression in single cells during normal cortical development and during cerebral organoid development28,29. A recent paper used droplet-based single-cell mRNA sequencing to analyse gene expression in 80,000 cells from 31 brain organoids after 3 and 6 months in vitro28. Using principal component analysis, 10 distinct populations of cells (clusters) were identified in 6-month old organoids. These included astrocytes, neuroepithelial progenitors (including cells with oligodendrocyte precursor cell-like identity), neuronal lineage cells, cells enriched for forebrain markers, and cells expressing retina-specific genes. Further analyses of the forebrain and retinal cells identified transcriptionally distinct subclusters of cells. As one might expect, 6-month-old organoids presented a greater diversity of cell types than 3-month-old organoids, as well as enrichment of genes associated with neuronal and glial maturation.

This study built on earlier single-cell work on organoid cell type diversity29 and provided the largest-to-date molecular map of the diversity of cell types generated. However, it also highlighted several challenges and caveats of the organoid protocol. For example, a large number of cells were assigned to a mesodermal lineage, emphasizing the variability inherent in the protocol. Also, the authors observed that some cell types were only produced by a subset of organoids and that organoids grown in the same bioreactor tended to be similar in terms of their ability to make cells of each cluster, suggesting that batch effects and local microenvironments are important in patterning and possibly that organoids secrete signalling factors that influence sister organoids. In addition, not all cell clusters in every organoid were assigned to a specific cell type, indicating that variability between populations of cells can be driven by factors other than cell type (for example, batch effects) and/or that the identity of some cells is not strongly correlated to an in vivo counterpart. Interestingly, despite weak correlations between the transcriptional identity of organoid progenitor cells and their in vivo counterparts, organoid cells still differentiated reasonably accurately, implying that the differentiation cues are strong enough to drive correct maturation. Several reports suggest that long-term organoid culture can improve the correlation between the molecular signatures of organoid and endogenous cells28,52. These studies highlight the importance of analysing molecular signatures that reflect cell type and regional identity because although appropriate developmental cues can be replicated in vitro, specific off- target cell signatures can often be found. Understanding these signatures is fundamental to developing more robust models.

Fusing organoids to model complex structures and circuit formation

The ‘extrinsic’ organoid model whereby patterning is influenced by externally added molecules rather than relying on intrinsic self-organization shows promise with regard to better reproducibility5,6,25. In a recent study in which pallial and subpallial spheroids were generated and characterized by single-cell analysis, no cells with a mesodermal or endodermal identity were found6. Creating isolated regional identities does, of course, restrict the ability to recapitulate certain aspects of brain architecture and connectivity. For example, in the developing cortex, excitatory neurons originate from the dorsal (pallial) cortex, whereas inhibitory cortical neurons arise from the ventral (subpallial) forebrain53. A dorsal cortex organoid will therefore lack inhibitory interneurons, a limitation for studying formation or function of cortical circuits. Some researchers are tackling this problem by fusing organoids of different regional identities6,26. For example, the fusion of human cortical spheroids and human subpallial spheroids was used to model the migration of interneurons from the subpallium to the cortex6. Interneuron migration was previously reported in an ‘extrinsic’ cerebral organoid model2; however, the later study exploited the reproducibility afforded by directed differentiation. The subpallial spheroids were initially patterned with SMAD inhibition and then exposed to molecules known to confer ventral identity6. Following long-term culture, several GABAergic interneuron subtypes were observed. Furthermore, single-cell transcriptional profiling revealed that glutamatergic neurons and intermediate progenitors were produced in pallial cortical spheroids, whereas GABAergic cells and oligodendrocyte progenitors were produced in the subpallial spheroids (both conditions produced astroglia). The organoid-derived interneurons migrated in a manner similar to that of their in vivo counterparts.

These findings were further supported by another report documenting interneuron migration following fusion of dorsal and ventral brain organoids26, and both studies demonstrated disruption of migration by antagonism of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), which has an important role in interneuron migration6,26. It will be interesting to see if these systems can replicate the directionality afforded by guidance cues in vivo and whether the organoid interneurons secrete molecules that can locally influence progenitor cell populations in the cortex as has been shown in vivo54. If so, these models could help to address fundamental questions regarding cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous contributions to migratory routes and the establishment of cortical circuits.

Modelling epigenomic remodelling

The temporal transcriptional precision that drives human brain development is also influenced by the activity of numerous regulatory elements along with global remodelling of the epigenome55. It is therefore important to assess epigenomic remodelling during organoid differentiation. A recent study analysed DNA methylation in brain organoids and revealed that, although some patterns were conserved between fetal tissue and brain organoids, others were specific to in vitro conditions52. This again emphasizes the importance of continued validation of models and protocols with reference to the developing human brain.

Understanding self-organization

Despite differences in protocols, all organoids undergo some extent of self-organization; however, the mechanisms of self- organization are not well understood. A recent study characterized cerebral organoids by demonstrating the presence of both distinct cerebral brain regions and forebrain organizing centres56. Immunohistochemical analyses revealed that several organoids contained a cell population that resembled the cortical hem, an important signalling centre implicated in forebrain patterning57,58. In human development, the cortical hem expresses WNT and BMP genes59,60 and is an important organizing centre instructing the formation of the hippocampus57 and the dorsoventral patterning of the neocortex58. Although the presence of a cortical-hem-like region had been noted in an earlier report3, the organoid tissue examined in the later study also expressed signalling molecules, including WNT2B and BMP6. This suggests that hem-like signalling centres can participate in the self-organization of cerebral organoids, mimicking the endogenous patterning of the developing brain. It remains to be seen, however, to what extent these centres have a functional role in organoid organization and whether they can reproducibly generate organoids with more complex regional organization.

Establishing functional cortical circuits

A major limitation of organoid modelling is the lack of evidence of the establishment of faithful cortical circuits; however, some progress has been reported on this front. A degree of neuronal functional maturation was reported in dorsal telencephalon organoids that were allowed to develop for up to 180 days in vitro25. Neurons fired action potentials spontaneously, there was evidence of synaptogenesis and excitatory postsynaptic potentials were evoked in response to extracellular electrical stimulation, suggesting neuronal connectivity. The formation of the human cerebral cortex in vivo involves the assembly of canonical circuits composed of glutamatergic neurons that are generated in the dorsal forebrain and GABAergic interneurons that are produced in the ventral forebrain53,61. In the dorsal-ventral fused model mentioned earlier6, cells that migrated from the subpallial spheroid to the cortical spheroid expressed cortical interneuron markers, and whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings demonstrated that these interneuron-like cells can receive excitatory inputs from cells in the dorsal cortical organoids; conversely, the cells in the dorsal cortical organoids can receive inputs from the inhibitory interneurons. The cells that had migrated into the cortical spheroids also fired action potentials at twice the rate of cells in unfused subpallial spheres or non-migrated cells in the fused organoid, suggesting maturation of membrane properties. Increased complexity of branching and morphological evidence of synapses between GABAergic interneurons and cortical neurons were also reported. Thus, pre-patterned organoids can fuse and form functional interconnections.

In addition to these findings, electrophysiological studies have demonstrated functional synapses in several brain organoid models25,28, and electron microscopy has confirmed the presence of structurally defined synaptic junctions28. Recently, it was demonstrated that photosensitive cells in retinal-like regions of brain organoids can respond to light28. However, the extent to which the synapses that form between neurons in organoids reflect the normal microcircuits in the developing brain remains unclear. Most human cortical circuits develop postnatally, and many take years to mature. The problems of circuit maturation and the development of relevant cortical circuits will be significant challenges for scientists to overcome.

Challenges

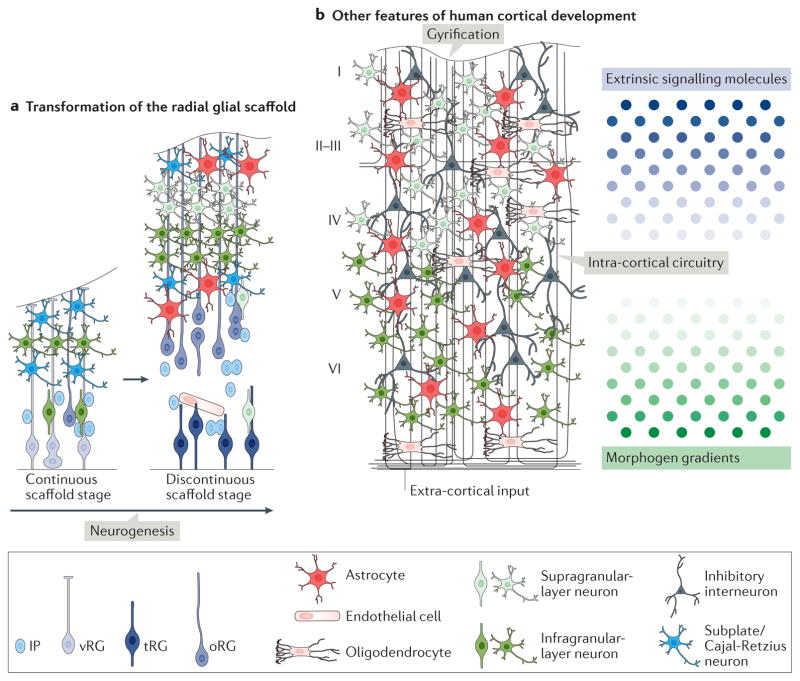

Despite considerable progress, many issues remain. Brain organoids currently lack some of the cell types present in primary cortex, such as endothelial cells (which have been shown to influence progenitor cell behaviour62,63) and microglia (which also have a role in early stages of cortical development64) (FIG. 2b). Organoids show structural features of ventricular zones and some aspects of cortical layering (FIG. 2a), but additional levels of cortical organization such as the radial glial scaffold, gyrification, proper cortical layering and the specificity of neuronal connections remain to be established and need to be compared to patterns observed in primary tissue (FIG. 3). An overriding issue regarding brain organoids as a model of development is their relative immaturity. Most protocols show transcriptional correlation with only early to mid-gestational stages of brain development5,25,29. If, and how, later stages of development can be modelled remains to be seen.

Figure 3. Aspects of human cortical development for future exploration in brain organoid models.

Several interesting aspects of human cortical development are yet to be explored in brain organoid models. a | A developmental switch from a continuous radial glial scaffold to a discontinuous scaffold and the generation of radial glial cells with non-classical morphologies (such as truncated radial glial cells (tRGs)) was recently described90 and could be examined in organoid models. It was shown that during early neurogenesis (the continuous scaffold stage), the basal fibres of ventricular radial glial cells (vRGs) contact the pial surface and that newborn neurons migrate along the fibres of both vRGs and outer radial glial cells (oRGs). During late neurogenesis (the discontinuous scaffold stage), newborn neurons reach the cortical plate only along oRG fibres. If these structures are recapitulated in human organoids, time-lapse imaging of migrating neurons could be used to demonstrate this developmental switch. b | Another feature of human cortical development to be explored is the cortical folding that takes place largely after neurogenesis is complete, which has yet to be properly modelled in organoids. In addition, the establishment of correct lamination replicating the six layers (I–VI) of the mammalian cortex has not yet been replicated in organoids. Extracortical input and canonical intracortical circuits, including those mediating inhibition, have not yet been fully demonstrated in organoids, and the roles of extrinsic signalling via morphogens and other diffusible cues remain largely unexplored. IP, intermediate progenitor cell. Part a adapted with permission from REF. 90, Elsevier.

Organoids as models of brain disease

Although animal models of neurodevelopmental diseases have been essential for our current understanding of pathological mechanisms, there are obvious species differences that limit their resemblance to human diseases, including differences in developmental programmes, cytoarchitecture, cell composition, and genetic background. Animal models have been particularly powerful in helping us to understand the role of an identified mutated gene in a disease phenotype. However, many uniquely human cognitive and behavioural diseases — such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or schizophrenia — present polygenic aetiology, making them difficult to study with existing animal models. Also, evolutionary species differences in the genomic landscapes that underlie intellectual abilities preclude the use of rodent models for many human behavioural disorders.

The advantages of in vitro models of human brain disease are numerous. They hold promise for the study of at least some features of disease in a 3D multicellular environment. Organoid models are also amenable to studies that require live, functioning tissue, such as the analysis of electrophysiological features or dynamic cell behaviours. Additionally, organoids derived from patients harbouring genetic diseases afford the possibility of studying disease mechanisms. In particular, the use of patient-derived iPSCs provides a unique opportunity to model complex polygenic disorders, including those with unidentified risk loci.

The possibilities of disease modelling have expanded with the evolution of genome editing tools65, which allow for the introduction of precise, targeted mutations or targeted gene repair. These manipulations are easily applied to organoid systems51,66, fuelling a burgeoning interest in the application of this technology to understand the pathophysiology of a wide range of adult and developmental human brain diseases. However, it remains to be seen if embryonic-stage organoids can be used to model neurodegenerative diseases of the ageing brain or neurodevelopmental diseases that manifest at later, postnatal stages.

Modelling neurodevelopmental disorders

Given the resemblance of organoid models to early stages of cortical neurogenesis, they may be best suited for modelling developmental disorders that manifest at embryonic or fetal stages. An example is provided by a study that reported the use of iPSCs derived from a microcephalic patient carrying a mutation in the gene encoding CDK5 regulatory subunit-associated protein 2 (CDK5RAP2)2. Cerebral organoids grown from these cells contained fewer proliferating progenitor cells and showed premature neural differentiation compared to wild-type counterparts. This study thus suggested a mechanism underlying the microcephalic phenotype observed in patients.

In some instances, brain organoids have recapitulated disease phenotypes observed in mouse models, validating both models50. However, they can also be used to discover human-specific phenotypes, providing an advantage over existing mouse models. Two recent papers used brain organoids to investigate the cellular basis of Miller–Dieker syndrome (MDS), a severe congenital form of lissencephaly50,67. Classically, lissencephaly has been studied in mouse models, which have the obvious disadvantage of being naturally lissencephalic. Although gyrification is not yet well recapitulated in human brain organoids, they may contain the relevant cell types or developmental programmes necessary to investigate these diseases. iPSCs derived from individuals with MDS were used to generate cerebral organoids that exhibited several developmental phenotypes reported in lissencephaly mouse models, including dysregulation of the neuroepithelial stem cell mitotic spindle and neuronal migration defects50. The organoids also displayed severe apoptosis of neuroepithelial stem cells in the ventricular-like zone and a mitotic defect in oRGs50. A second report also observed changes in the division mode of radial glial cells in MDS organoids and identified non-cell-autonomous defects in WNT signalling as an underlying mechanism67.

The recent outbreak of Zika virus (ZIKV) in the Americas has also highlighted the potential uses, and limitations, of organoid modelling. In early 2016, despite a correlation between the ZIKV epidemic and an increase in cases of congenital microcephaly, there was no direct experimental evidence that ZIKV infection causes birth defects. The use of brain organoids helped to demonstrate a causal relationship between ZIKV infection and the selective targeting and destruction of neural progenitor cells. A study using 2D iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells68 and two later studies69,70 that used both 2D neural precursor cells (NPCs) and brain organoids demonstrated this association. One study showed that brain organoids exposed to ZIKV undergo a growth reduction69, whereas another reported reductions in progenitor cell and neuron numbers due to apoptosis70. Further studies used forebrain organoids to reveal cell-specific viral tropism, selective effects on NPC proliferation5, and upregulation of the innate immune receptor Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) after ZIKV infection71. Pathway analysis of gene expression changes during TLR3 activation highlighted several genes related to neuronal development, suggesting a mechanistic connection to disrupted neurogenesis.

However, the organoids used to investigate ZIKV infection do not precisely reflect human brain tissue architecture and cell type composition (see above). Consequently, the interpretation of cell type infectivity and its significance in human disease may be biased. Studies using organoids and primary tissue both found high infectivity of NPCs; however, infection of astrocytes was only occasionally observed in organoids5 but was abundantly present in primary tissue72. It is unclear if this was due to an under-representation of astrocytes in the organoids or inherent differences between in vitro- and in vivo-derived cells.

The use of primary tissue also highlighted the vulnerability of microglia to ZIKV infection72. As noted above, this cell type is usually missing from organoid models, which may be significant when considering viral entry mechanisms. Indeed, single-cell RNA-seq data from human primary tissue revealed that the candidate viral entry receptor, AXL (also known as tyrosine-protein kinase receptor UFO), is highly expressed by human cortical radial glial cells, astrocytes, endothelial cells, and microglia, as well as in radial-glia-like cells of brain organoids73. Blocking the AXL receptor reduced ZIKV infection of PSC-derived astrocytes in vitro, and genetic knockdown of AXL in a glial cell line nearly abolished infection. However, a study using human iPSC-derived NPCs or early-stage cerebral organoids demonstrated that genetic ablation of AXL did not affect ZIKV entry or ZIKV-mediated cell death74. These seemingly contradictory findings were potentially explained by another study reporting that AXL is a crucial receptor for infection of human glial cells (astrocytes and microglia) but not of human NPCs75. The importance of AXL (or other receptors and pathways implicated in glial ZIKV infection) and the enhanced susceptibility of astrocytes and microglia to infection could have easily been overlooked based on brain organoid models alone, suggesting that more sophisticated organoids may be required for some aspects of disease modelling and drug discovery.

Modelling psychiatric diseases

2D iPSC models have been important for analysing parameters such as gene expression, cell morphology, neuronal excitability, and synapse formation76,77 and have shed light on mechanisms underlying disorders such as schizophrenia78,79, bipolar disorder78–80, and Rett syndrome81 (for discussion, see REF. 82). Organoid modelling, with its more complex tissue structure, offers new possibilities. In a recent study, forebrain organoids were generated from four patients with severe idiopathic ASD and from their unaffected first-degree relatives83. Patient-derived organoids exhibited dysregulation of forkhead box G1 expression (an important gene for fore-brain development), accelerated cell cycle progression and increased production of GABAergic neurons. Keeping in mind the caveats of whole-organoid transcriptome analyses (such as composition differences across organoids), this demonstrates how organoid modelling can be used to identify molecular and cellular alterations that may underlie neuropsychiatric disorders.

Brain organoids have also been used to model Timothy syndrome, a severe neurodevelopmental disease characterized by ASD and epilepsy6. iPSCs from three patients with Timothy syndrome were used to generate dorsal and ventral forebrain organoids, which were subsequently fused to model interneuron migration. This revealed a cell-autonomous migration defect in Timothy syndrome-derived interneurons. As more diverse disease phenotypes are reported in organoids, it will be important for the disease features to be replicated by multiple laboratories in order to support their true relevance.

Many neuropsychiatric diseases manifest defects in processes that unfold postnatally, such as circuit formation, synaptic pruning, dendritic growth and cortical circuit refinement. These neuronal networks can take years to mature in the human brain and rely on subcortical influences, calling into question the ability of organoid models to accurately reflect these complex interrelated features of brain development.

Modelling neurodegenerative diseases

It is also unclear how much insight can be gained by using organoids to model neurodegenerative diseases. Studies have suggested that brain organoids may be relevant models, even for late-onset diseases such as Alzheimer disease (AD). The amyloid hypothesis of AD posits that excessive accumulation of amyloid-β peptide leads to neurofibrillary tangles composed of aggregated hyperphosphorylated tau84. 2D cell cultures may not provide the complex extracellular environment necessary to model extracellular protein aggregation, making 3D tissue-like structures an arguably more promising model. Indeed, one study revealed that familial AD (FAD) mutations in β-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 induced robust extracellular deposition of amyloid-β in a human neural stem-cell-derived 3D culture system85. Furthermore, the 3D-differentiated neuronal cells expressing FAD mutations exhibited aggregates of phosphorylated tau as well as filamentous tau. These findings were supported by another group using brain organoids derived from multiple patients with FAD: again, AD-like pathologies such as amyloid aggregation, hyperphosphorylated tau protein, and endosome abnormalities were seen86. These findings are important because this phenotype has not been reported in mouse models with FAD mutations.

Several drugs that have shown promising results in Alzheimer mouse models have failed to prevent cognitive decline in late-phase clinical trials87–89. Brain organoids are amenable to drug treatment, and it has been shown that disease phenotypes can be recapitulated across multiple cell lines derived from different patients with AD. Such studies offer hope that brain organoids might act as a drug discovery platform for neurodegenerative disease. Of course, not all aspects of brain structure and function will be modelled by these tissue structures, but perhaps the most precocious events in disease aetiology can be captured and investigated, and these may share mechanistic pathways with disease features that manifest at later stages.

Conclusions and future directions

The brain organoid model is in an early phase of development. How scientists respond to the challenges of using this system will determine how widely it is adopted. Extensive molecular characterization of cell types is fundamental to understanding to what extent in vitro-derived cells resemble their in vivo human counterparts. Given the heterogeneity of cell composition in organoids, single-cell mRNA sequencing offers a major advantage for molecular characterization, and further understanding of transcriptional programmes in fetal cell types and normal developmental programmes will also be important. With continued in-depth studies, protocols can be assessed and improved to better reflect human development. Bioengineering techniques will be important for adding in structural features that are normally present in the developing human brain. For example, a network of infiltrating structures could carry and distribute important nutrients to the organoid. Such techniques might allow larger and more complex organoids to form and allow modelling of later fetal stages. PSC-derived cell types could also be differentiated separately and integrated into the organoid model. It will be interesting to see how far current protocols can be pushed. For example, can brain organoids model human features of cortical architecture, including recently identified developmental changes in the glial scaffold90 (FIG. 3a)? Once robust protocols are established, a plethora of techniques from lineage tracing to live imaging can be applied to probe important unanswered questions concerning human brain development.

In conclusion, the capacity of organoids to differentiate, self-organize, and form distinct, complex, biologically relevant structures makes them ideal in vitro models of development, disease pathogenesis, and platforms for drug screening. They hold the promise of better relevance for understanding human brain development and disease than current rodent models. The failure of many neurotherapeutic approaches to translate from animal models to clinical practice underscores the need for better predictive models, and brain organoids may help bridge this divide. However, to take full advantage of this potential, we must acknowledge the strengths and the limitations of current organoid modelling systems. The diverse cell types that can be represented in an organoid can be an advantage for modelling complex cellular interactions, but future studies must validate the extent and reproducibility of composition differences. The slow maturation of organoids may limit studies of later developmental events or stages of disease expression; however, disease phenotypes that manifest at early stages may be aptly modelled. Finally, the absence of cell types involved with normal brain development and circuit function, the variation in structural features of cell and tissue architecture, and the need for more comprehensive transcriptional network matching between organoid and fetal tissue will need to be overcome to realize the full potential of these systems as models for human brain development and disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A. Bhaduri, J. Spatazza, T. Nowakowski, M. Bershteyn, H. Retallack, M. A. Mostajo Radji and A. Pollen for their scientific discussions and thoughtful input. The authors are very grateful to T. Nowakowski for his help with the illustrations. This work was supported by funding from the US National Institutes of Health R35NS097305.

Glossary

- Self-organization

The capacity to autonomously generate the architectural complexity of vertebrate organs.

- Inductive signals

Molecular signals that can influence the developmental fate of a cell.

- Outer radial glial cells

A subclass of radial glial cell residing primarily in the outer subventricular zone.

- Morphogens

Secreted factors that can induce different cell fates across a sheet of cells in a concentration-dependent manner by forming gradients.

- Bioreactors

A manufactured or engineered device that supports a biologically active environment.

- Intermediate progenitors

Transient-amplifying cells that can produce neurons or new intermediate progenitor cells.

- RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

A high-throughput method to sequence whole-genome cDNA in order to obtain quantitative measures of all expressed RNAs in a tissue.

- Principal component analysis

A mathematical algorithm that reduces the dimensionality of data while retaining important variation.

- Single-cell transcriptional profiling

RNA sequencing of single cells.

- Regulatory elements

Sequences of a gene that are involved in regulation of genetic transcription.

- Epigenome

A multitude of biochemical modifications to DNA that have key roles in regulating genome structure and function, including the timing, strength, and memory of gene expression.

- Forebrain organizing centres

Groups of cells that send signals that induce distinct fates in neighbouring cells, resulting in spatial patterning in the forebrain.

- Viral tropism

The specificity of a virus for a particular host cell.

Footnotes

Author contributions

E.D. researched the data for the article and provided a substantial contribution to discussions of the content. E.D. and A.R.K. contributed equally to writing the article and to review and/or editing of the manuscript before submission.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tiscornia G, Vivas EL, Belmonte JCI. Diseases in a dish: modeling human genetic disorders using induced pluripotent cells. Nat Med. 2011;17:1570–1576. doi: 10.1038/nm.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lancaster MA, et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature. 2013;501:373–379. doi: 10.1038/nature12517. This was the first paper to introduce a method for generating cerebral organoids. The organoids were used to model microcephaly. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadoshima T, et al. Self-organization of axial polarity, inside-out layer pattern, and species-specific progenitor dynamics in human ES cell-derived neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20284–20289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315710110. This study provided a detailed exploration of brain organoid tissue including the temporal and spatial organization of cell type diversity and patterning. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jo J, et al. Midbrain-like organoids from human pluripotent stem cells contain functional dopaminergic and neuromelanin-producing neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian X, et al. Brain-region-specific organoids using mini-bioreactors for modeling ZIKV exposure. Cell. 2016;165:1238–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.032. This study used mini bioreactors to produce forebrain organoids with a well-defined OSVZ and demonstrated the presence of oRGs with defined molecular markers. Diverse neuronal cell types expressing molecular markers of all six cortical layers were observed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birey F, et al. Assembly of functionally integrated human forebrain spheroids. Nature. 2017;545:54–59. doi: 10.1038/nature22330. This study used pre-patterned pallial and subpallial spheroids to form fused forebrain spheroids, demonstrating interneuron diversity, migration and integration. This organoid model was used to model Timothy syndrome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakaguchi H, et al. Generation of functional hippocampal neurons from self-organizing human embryonic stem cell-derived dorsomedial telencephalic tissue. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8896. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monzel AS, et al. Derivation of human midbrain-specific organoids from neuroepithelial stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2017;8:1144–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muguruma K, Nishiyama A, Kawakami H, Hashimoto K, Sasai Y. Self-organization of polarized cerebellar tissue in 3D culture of human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep. 2015;10:537–550. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suga H, et al. Self-formation of functional adenohypophysis in three-dimensional culture. Nature. 2011;480:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature10637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eiraku M, et al. Self-organized formation of polarized cortical tissues from ESCs and its active manipulation by extrinsic signals. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:519–532. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weitzer G. In: Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Barrett JE, et al., editors. Springer; 2004. pp. 21–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang SC, Wernig M, Duncan ID, Brüstle O, Thomson JA. In vitro differentiation of transplantable neural precursors from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edri R, et al. Analysing human neural stem cell ontogeny by consecutive isolation of Notch active neural progenitors. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6500. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi Y, Kirwan P, Smith J, Robinson HPC, Livesey FJ. Human cerebral cortex development from pluripotent stem cells to functional excitatory synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:477–486. doi: 10.1038/nn.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ying QL, Stavridis M, Griffiths D, Li M, Smith A. Conversion of embryonic stem cells into neuroectodermal precursors in adherent monoculture. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:183–186. doi: 10.1038/nbt780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaspard N, et al. An intrinsic mechanism of corticogenesis from embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2008;455:351–357. doi: 10.1038/nature07287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers SM, et al. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe K, et al. Directed differentiation of telencephalic precursors from embryonic stem cells. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:288–296. doi: 10.1038/nn1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eiraku M, et al. Self-organizing optic-cup morphogenesis in three-dimensional culture. Nature. 2011;472:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature09941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato T, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt–villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fietz SA, et al. OSVZ progenitors of human and ferret neocortex are epithelial-like and expand by integrin signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:690–699. doi: 10.1038/nn.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen DV, Lui JH, Parker PRL, Kriegstein AR. Neurogenic radial glia in the outer subventricular zone of human neocortex. Nature. 2010;464:554–561. doi: 10.1038/nature08845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi Y, Kirwan P, Livesey FJ. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to cerebral cortex neurons and neural networks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1836–1846. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paşca AM, et al. Functional cortical neurons and astrocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in 3D culture. Nat Methods. 2015;12:671–678. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagley JA, Reumann D, Bian S, Lévi-Strauss J, Knoblich JA. Fused cerebral organoids model interactions between brain regions. Nat Methods. 2017;14:743–751. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindborg BA, et al. Rapid induction of cerebral organoids from human induced pluripotent stem cells using a chemically defined hydrogel and defined cell culture medium. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5:970–979. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quadrato G, et al. Cell diversity and network dynamics in photosensitive human brain organoids. Nature. 2017;545:48–53. doi: 10.1038/nature22047. This study analysed gene expression in over 80,000 individual cells and found that organoids can generate a broad diversity of cells that are related to endogenous classes, including cells from the cerebral cortex and the retina. Neuronal activity within organoids was also controlled using light stimulation of photosensitive cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camp JG, et al. Human cerebral organoids recapitulate gene expression programs of fetal neocortex development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:15672–15677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520760112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki IK, Vanderhaeghen P. Is this a brain which I see before me? Modeling human neural development with pluripotent stem cells. Development. 2015;142:3138–3150. doi: 10.1242/dev.120568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrison-Uy SJ, Pleasure SJ. Wnt signaling and forebrain development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a008094. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hikasa H, Sokol SY. Wnt signaling in vertebrate axis specification. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;5:a007955. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Backman M, et al. Effects of canonical Wnt signaling on dorso-ventral specification of the mouse telencephalon. Dev Biol. 2005;279:155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ten Berge D, et al. Wnt signaling mediates self-organization and axis formation in embryoid bodies. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:508–518. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirkeby A, et al. Generation of regionally specified neural progenitors and functional neurons from human embryonic stem cells under defined conditions. Cell Rep. 2012;1:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nasu M, et al. Robust formation and maintenance of continuous stratified cortical neuroepithelium by laminin-containing matrix in mouse ES cell culture. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e53024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chenn A, Walsh CA. Regulation of cerebral cortical size by control of cell cycle exit in neural precursors. Science. 2002;297:365–369. doi: 10.1126/science.1074192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Machon O, et al. A dynamic gradient of Wnt signaling controls initiation of neurogenesis in the mammalian cortex and cellular specification in the hippocampus. Dev Biol. 2007;311:223–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Otani T, Marchetto MC, Gage FH, Simons BD, Livesey FJ. 2D and 3D stem cell models of primate cortical development identify species-specific differences in progenitor behavior contributing to brain size. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smart IHM, Dehay C, Giroud P, Berland M, Kennedy H. Unique morphological features of the proliferative zones and postmitotic compartments of the neural epithelium giving rise to striate and extrastriate cortex in the monkey. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:37–53. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lukaszewicz A, et al. G1 phase regulation, area-specific cell cycle control, and cytoarchitectonics in the primate cortex. Neuron. 2005;47:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zecevic N, Chen Y, Filipovic R. Contributions of cortical subventricular zone to the development of the human cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2005;491:109–122. doi: 10.1002/cne.20714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dehay C, Kennedy H. Cell-cycle control and cortical development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:438–450. doi: 10.1038/nrn2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martínez-Cerdeño V, et al. Comparative analysis of the subventricular zone in rat, ferret and macaque: evidence for an outer subventricular zone in rodents. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lui JH, Hansen DV, Kriegstein AR. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell. 2011;146:18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fish JL, Dehay C, Kennedy H, Huttner WB. Making bigger brains-the evolution of neural-progenitor-cell division. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2783–2793. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Tsai JW, LaMonica B, Kriegstein AR. A new subtype of progenitor cell in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:555–561. doi: 10.1038/nn.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pollen AA, et al. Molecular identity of human outer radial glia during cortical development. Cell. 2015;163:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ostrem B, Di Lullo E, Kriegstein A. oRGs and mitotic somal translocation - a role in development and disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2017;42:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bershteyn M, et al. Human iPSC-derived cerebral organoids model cellular features of lissencephaly and reveal prolonged mitosis of outer radial glia. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:435–449.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.12.007. This study used brain organoids to model lissencephaly. The authors identified a mitotic defect in oRGs and used single-cell RNA sequencing to identify cells presenting an oRG transcriptional signature in human brain organoids. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Y, et al. Induction of expansion and folding in human cerebral organoids. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:385–396. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luo C, et al. Cerebral organoids recapitulate epigenomic signatures of the human fetal brain. Cell Rep. 2016;17:3369–3384. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lodato S, Arlotta P. Generating neuronal diversity in the mammalian cerebral cortex. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2015;31:699–720. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100814-125353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voronova A, et al. Migrating interneurons secrete fractalkine to promote oligodendrocyte formation in the developing mammalian brain. Neuron. 2017;94:500–516.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bertrand N, Castro DS, Guillemot F. Proneural genes and the specification of neural cell types. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:517–530. doi: 10.1038/nrn874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renner M, et al. Self-organized developmental patterning and differentiation in cerebral organoids. EMBO J. 2017;36:1316–1329. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Subramanian L, Tole S. Mechanisms underlying the specification, positional regulation, and function of the cortical hem. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(Suppl 1):i90–i95. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caronia-Brown G, Yoshida M, Gulden F, Assimacopoulos S, Grove EA. The cortical hem regulates the size and patterning of neocortex. Development. 2014;141:2855–2865. doi: 10.1242/dev.106914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Furuta Y, Piston DW, Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) as regulators of dorsal forebrain development. Development. 1997;124:2203–2212. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grove EA, Tole S, Limon J, Yip L, Ragsdale CW. The hem of the embryonic cerebral cortex is defined by the expression of multiple Wnt genes and is compromised in Gli3-deficient mice. Development. 1998;125:2315–2325. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guo J, Anton ES. Decision making during interneuron migration in the developing cerebral cortex. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Javaherian A, Kriegstein A. A stem cell niche for intermediate progenitor cells of the embryonic cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:i70–i77. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stubbs D, et al. Neurovascular congruence during cerebral cortical development. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:i32–i41. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cunningham CL, Martínez-Cerdeño V, Noctor SC. Microglia regulate the number of neural precursor cells in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4216–4233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3441-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hockemeyer D, Jaenisch R. Induced pluripotent stem cells meet genome editing. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun Y, Ding Q. Genome engineering of stem cell organoids for disease modeling. Protein Cell. 2017;8:315–327. doi: 10.1007/s13238-016-0368-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iefremova V, et al. An organoid-based model of cortical development identifies non-cell-autonomous defects in wnt signaling contributing to Miller–Dieker syndrome. Cell Rep. 2017;19:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tang H, et al. Zika virus infects human cortical neural progenitors and attenuates their growth. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:587–590. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garcez PP, et al. Zika virus impairs growth in human neurospheres and brain organoids. Science. 2016;352:816–818. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cugola FR, et al. The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature. 2016;534:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nature18296. This report used a brain organoid model to demonstrate that ZIKV infection results in a reduction of proliferative zones and in disrupted cortical layers. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dang J, et al. Zika virus depletes neural progenitors in human cerebral organoids through activation of the innate immune receptor TLR3. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Retallack H, et al. Zika virus cell tropism in the developing human brain and inhibition by azithromycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:14408–14413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618029113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nowakowski TJ, et al. Expression analysis highlights AXL as a candidate zika virus entry receptor in neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wells MF, et al. Genetic ablation of AXL does not protect human neural progenitor cells and cerebral organoids from zika virus infection. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meertens L, et al. Axl mediates ZIKA virus entry in human glial cells and modulates innate immune responses. Cell Rep. 2017;18:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wen Z, Christian KM, Song H, Ming GL. Modeling psychiatric disorders with patient-derived iPSCs. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2016;36:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Flaherty EK, Brennand KJ. Using hiPSCs to model neuropsychiatric copy number variations (CNVs) has potential to reveal underlying disease mechanisms. Brain Res. 2017;1655:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brennand KJ, et al. Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;473:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Madison JM, et al. Characterization of bipolar disorder patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells from a family reveals neurodevelopmental and mRNA expression abnormalities. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:703–717. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mertens J, et al. Differential responses to lithium in hyperexcitable neurons from patients with bipolar disorder. Nature. 2015;527:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nature15526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marchetto MCN, et al. A model for neural development and treatment of Rett syndrome using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Quadrato G, Brown J, Arlotta P. The promises and challenges of human brain organoids as models of neuropsychiatric disease. Nat Med. 2016;22:1220–1228. doi: 10.1038/nm.4214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mariani J, et al. FOXG1-Dependent dysregulation of GABA/Glutamate neuron differentiation in autism spectrum disorders. Cell. 2015;162:375–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Choi SH, et al. A three-dimensional human neural cell culture model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2014;515:274–278. doi: 10.1038/nature13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Raja WK, et al. Self-organizing 3D human neural tissue derived from induced pluripotent stem cells recapitulate alzheimer’s disease phenotypes. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161969. This report used Alzheimer disease (AD) patient-derived iPSCs to recapitulate AD-like pathologies such as age-dependent amyloid aggregation, hyperphosphorylated tau protein, and endosome abnormalities in organoids and showed that treatment of patient-derived organoids with β- and γ-secretase inhibitors significantly reduces amyloid and tau pathology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Salloway S, et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:322–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Doody RS, et al. A phase 3 trial of semagacestat for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Doody RS, et al. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:311–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nowakowski TJ, Pollen AA, Sandoval-Espinosa C, Kriegstein AR. Transformation of the radial glia scaffold demarcates two stages of human cerebral cortex development. Neuron. 2016;91:1219–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]