Abstract

Purpose

To disclose, using an ex vivo study, the histopathological mechanism behind the in vivo thickening of the Endothelium/Descemet’s membrane complex (En/DM) observed in rejected corneal grafts (RCGs).

Methods

Descemet’s membrane (DM), endothelium (En), and retrocorneal membranes (RCM) make up the total En/DM thickness. These layers are non-differentiable by HD-OCT; therefore, the source of the thickening is unclear from an in vivo perspective. A retrospective ex vivo study (from September 2015 to December 2015) was conducted to measure the thicknesses of DM, En, and RCM in 54 corneal specimens (31 RCGs and 23 controls) using light microscopy. Controls were globes with posterior melanoma without corneal involvement.

Results

There were 54 corneas examined ex vivo with mean age 58.1 ± 12.2 in controls and 51.7 ± 27.9 years in rejected corneal grafts. The ex vivo study uncovered the histopathological mechanism of En/DM thickening to be secondary to significant thickening (p<0.001) of DM (6.5 ± 2.4 μm) in rejected corneal grafts compared to controls (3.9 ± 1.5 μm).

Conclusions

Our ex vivo study shows Descemet’s membrane is responsible for the thickening of the En/DM in RCGs observed in vivo by HD-OCT and not the endothelium or retrocorneal membrane.

Keywords: cornea histopathology, corneal graft rejection, Descemet’s membrane

Introduction

Despite the cornea’s immune privileged status, 29% of corneal transplants performed by penetrating keratoplasty fail due to rejection.1,2 Respectively, grafts with at least one rejection episode had an almost 3 year shorter mean survival than those with none.1 An immunological reaction against the donor’s endothelial cell layer is responsible for most of these episodes (endothelial rejection). Destruction of these non-regenerating cells results in corneal edema and graft failure. Therefore, identifying rejection episodes is paramount to promptly treat them and prolong graft survival.2 Unfortunately, no gold standard exists to monitor and reliably diagnose rejection episodes in follow up.

Tissue basement membrane thickening has been established as evidence of graft rejection in renal, hepatic, and lung grafts. Likewise, this thickening has been suggested to predict graft survival and immunological status.3–7 Evaluating the basement membrane in other organ transplants requires invasive biopsies but corneal transplants are transparent allowing for non-invasive evaluation through ocular imaging modalities. It has been demonstrated in the past that high definition optical coherence tomography (HD-OCT) can measure the Endothelial/Descemet’s membrane complex (En/DM) thickness in vivo.8–10 Our prior work showed thickening of the En/DM is occurring in corneal grafts undergoing rejection similarly to other rejected organ transplants. We also demonstrated the En/DM thickness can possibly serve as a diagnostic index for graft rejection with better sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy than the central corneal thickness (CCT).11 However, this study was restricted by the resolution of HD-OCT that was unable to differentiate the En/DM’s individual layers (endothelium, Descemet’s membrane, and the retrocorneal membrane, if present). Therefore, we were not able to identify the source of the thickening.

The aim of the current study was to address this limitation and assess a new factor of corneal graft rejection. We conducted a retrospective histopathological ex vivo study that further examined the individual layers of the En/DM under light microscopy to disclose the histopathological mechanism behind the changes observed on HD-OCT.

Methods

Study Population

For this retrospective study, initially 77 patients with rejected corneal grafts that underwent replacement surgery were identified by chart review from the year 2013 to 2015. Similarly, over 200 control samples were identified by review of the Florida Lions Ocular Pathology Laboratory (FLOPL) database at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute from 1998 to 2015. Controls were globes with choroidal melanoma posterior to the lens without corneal or angle involvement. All samples were paraffin sections (4 μm in thickness) of the corneal tissues obtained from the FLOPL and assessed for histological characteristics. All slides had been prepared with hematoxylin, eosin, and Periodic Acid-Schiff base stains within 24 hours of surgical removal after formalin fixing with paraffin embedding. Control corneas that were determined not to be clear and unremarkable were also excluded (guttata present, poor PAS staining, obvious stromal infiltration, and/or any other abnormal findings). For both groups, samples unmeasurable due to degradation, tissue folding, or other reasons were removed from the study. This resulted in 31 rejected corneal grafts (13 male, 18 female) and 23 control samples (15 male, 8 female). The University of Miami institutional review board approved the pathology review.

Ex Vivo Histopathological Study

Three thickness measurements at the center of each corneal specimen were obtained that included the CCT, central Descemet’s membrane thickness (DMT), and if present the central endothelium and retrocorneal membrane. Measurements were performed using an Olympus BH-2 light microscope (Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) with an eyepiece reticle calibrated to measure 2.25, 4.50, and 9.00 μm increments at 400×, 200× and 100× magnification.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis utilizing a two-sided Student t-test with p-values less than 0.05 considered to be statistically significant. Values are presented as means ± standard deviation.

Results

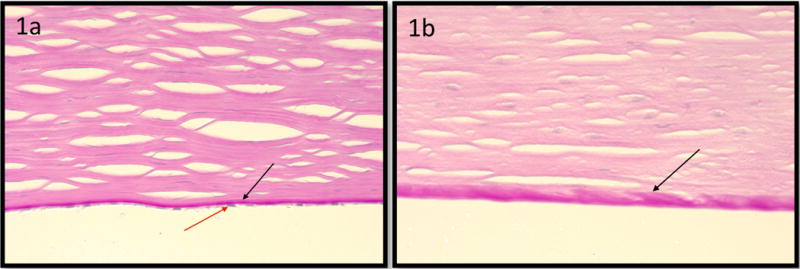

The ex vivo study disclosed a significant difference between the central Descemet’s membrane thickness (6.53 ± 2.35 μm) in rejected corneal grafts (RCGs) compared to the controls (3.91 ± 1.54 μm, p<0.001, Figure 1). There was no significant difference in the ex vivo CCT between the two groups as shown in Table 1 (p=0.147). Upon chart review, 27 out of the 31 patients had confirmed graft failure secondary to endothelial rejection. The remaining 4 had presumed rejection based on the patients’ clinical history. 11 patients had glaucoma and 17 did not. Descemet’s membrane thickness was not significantly different between these two sub-groups (p= 0.712). Knowledge of the presence or absence of glaucoma was unknown for 3 patients.

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs showing Descemet’s membrane in a rejected corneal graft is thicker than that of the control cornea: Image (1a) demonstrates Descemet’s membrane (black arrow, 1a) in a clear graft (Periodic acid-Schiff stain; original magnification, ×400). Note Descemet’s membrane (black arrow, 1a) and endothelium (red arrow, 1a). Image (1b) demonstrates a rejected corneal graft (Periodic acid-Schiff stain; original magnification, ×400). Note the absence of endothelial cells.

Table 1.

Ex Vivo Central Corneal Measurements:

| Control Group | Rejected Corneal Grafts | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 23 | 31 | |

| Corneal Age (years) | 58.1 ± 12.2 (37.0–79.0) |

51.7 ± 27.9 (28.0–88.0) |

0.314 |

| CCT (μm) | 451.17 ± 103.98 (261.00–630.00) |

509.54 ± 165.54 (144.00–855.00) |

0.147 |

| DMT (μm) | 3.91± 1.54 (2.25–6.75) |

6.53 ± 2.35 (4.50–11.25) |

<0.001 |

| Endothelium Thickness (μm) | 2.57 ± 1.00 | Not Present | |

| Retrocorneal Membrane Thickness (μm) | Not Present | 3.75 ± 2.60 (3 samples) |

Data presented as mean ± std (range)

Sig.: significance.

CCT = Central Corneal Thickness

DMT= Central Descemet’s Membrane Thickness

The corneal age in the control group was the age of the patient at the time the eye was surgically removed. Nevertheless, in the rejected grafts group the corneal age of the graft was calculated as the sum of the age of the donor and the time from grafting surgery until the time of resection of the graft and submitting it to histopathological evaluation. This information was absent in 4 specimens in the rejected corneal grafts group.

There was no significant difference between the ages of the RCGs and controls (p=0.314). The corneal age in the control group was the age of the patient at the time the eye was surgically removed. Nevertheless, in the RCGs group, the corneal age of the graft was calculated as the sum of the age of the donor and the time from grafting surgery until the time of resection of the graft and submitting it to histopathological evaluation. The average time from initial grafting surgery to resection (regrafting) was 8.0 ± 12.0 yrs. This information was not available for 4 specimens of the RCGs group. The average time between the onset of rejection and corneal transplant replacement surgery was 10.4 ± 12.3 months. This information was not available for 9 specimens of the RCGs group. All control specimens had endothelium but each rejected graft lacked it (Figure 1). A central retrocorneal membrane was observed in only 3 RCGs specimens and in none of the control specimens.

Discussion

In our previous in vivo investigation, we established the total Endothelial/Descemet’s membrane complex (En/DM) thickness measured in vivo by HD-OCT as a diagnostic index for corneal graft rejection. It was a more accurate, sensitive, and specific index of rejection than the central corneal thickness (CCT) both in actively rejecting and rejected corneal grafts.11 We also compared the En/DM thickness relative to the thickening of the entire cornea in both groups. This ratio was greater than one suggesting there was intrinsic thickening within the En/DM layers. The ratio was even greater in rejected grafts compared to actively rejecting grafts. This thickening was not entirely due to edema where in non-immunologically failed grafts the ratio was equal to one.11 En/DM thickening may have resulted from deposition of metabolic and/or immune end products as a graft undergoes rejection. Unfortunately, we were unable to differentiate the components of the En/DM and identify the source of the thickening. This initiated us to conduct this ex vivo histopathological study to investigate the histological changes of the En/DM in rejected corneal grafts (RCGs).

Of the three layers, corneal endothelial cells produce the posterior amorphous region of their basement membrane analogous to that of other body organs to form Descemet’s membrane.12 A thickened laminated Descemet’s membrane along with the presence of retrocorneal membranes has been observed in RCGs previously under light microscopy.13 Our prior investigation actually observed a fibrous retrocorneal membrane in 4 out of 9 rejected grafts when examined ex vivo.11 As a result of this ex vivo study, we put forth data here to establish Descemet’s membrane as the source of the thickening of the En/DM in rejected corneal grafts. We also demonstrate the unreliability of the CCT that was not significantly different in RCGs compared to controls. Much of the CCT thickening observed is caused by edema that likely had been removed by the alcohol dehydration process during preparation of the pathology slides. Interestingly, this did not seem to be the case with Descemet’s membrane indicating an underlying immune process may be occurring. Future directions should examine the pathogenic mechanism behind the thickening of Descemet’s membrane.

Our ex vivo study has its limitations including a small sample size. We assumed 4 of the RCGs with unknown history failed due rejection but may have had tissue failure unrelated to rejection. With respect to the control group, grafts that have undergone full thickness penetrating keratoplasty without prior history of rejection episodes would have been ideal. Cadavers are the only source of these samples and therefore very difficult to obtain. Another comparison could have been corneal removal in controls immediately after the whole eye had been enucleated. While the storage media were the same, the RCGs group and controls group were slightly different (cornea only vs whole globe). An artifact in either may have induced tissue thickening.

This study was not conducted on the same eyes included in the past in vivo study or on actively rejecting corneal grafts.11 Neither study correlated the En/DM or Descemet’s thickening with rejection duration or clinically determined severity of graft rejection. To address these limitations, future longitudinal research should look at a single study group (from day of transplant to complete rejection) and study the histopathology of the same in vivo eyes after excision for regrafting or a subject’s expiration.

This ex vivo study has disclosed thickening of the En/DM measured in vivo by HD-OCT is due to Descemet’s membrane and not the endothelium or retrocorneal membrane. Knowing the source of the thickening improves the understanding of the pathogenesis of graft rejection and mechanism behind in vivo observations. This may have the potential to disclose new pathways of graft rejections and thus new treatment modalities.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by a NEI K23 award (K23EY026118), NEI core center grant to the University of Miami (P30 EY014801), and Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB). The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Disclosure

This study was presented at the Fall Educational Symposium of the Cornea Society during the American Academy of Ophthalmology Meeting, October 14th, 2016 in Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.Williams KA, Keane MC, Galettis RA, et al. The Australian Corneal Graft Registry 2015 Report. Flinders University Press; Adelaide: 2015. pp. 116–127. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guilbert E, Bullet J, Sandali O, et al. Long-term rejection incidence and reversibility after penetrating and lamellar keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:560–569 e562. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aita K, Yamaguchi Y, Horita S, et al. Thickening of the peritubular capillary basement membrane is a useful diagnostic marker of chronic rejection in renal allografts. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:923–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roufosse CA, Shore I, Moss J, et al. Peritubular capillary basement membrane multilayering on electron microscopy: a useful marker of early chronic antibody-mediated damage. Transplantation. 2012;94:269–274. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31825774ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimizu T, Ishida H, Shirakawa H, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of transplant glomerulopathy cases. Clin Transplant. 2009;23(Suppl 20):39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taddesse-Heath L, Kovi J. Electron microscopic findings in hepatic allograft rejection. J Natl Med Assoc. 1994;86:779–782. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddiqui MT, Garrity ER, Martinez R, et al. Bronchiolar basement membrane changes associated with bronchiolitis obliterans in lung allografts: a retrospective study of serial transbronchial biopsies with immunohistochemistry [corrected] Mod Pathol. 1996;9:320–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shousha MA, Perez VL, Wang J, et al. Use of ultra-high-resolution optical coherence tomography to detect in vivo characteristics of Descemet’s membrane in Fuchs’ dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1220–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tao A, Chen Z, Shao Y, et al. Phacoemulsification induced transient swelling of corneal Descemet’s Endothelium Complex imaged with ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchings N, Simpson TL, Hyun C, et al. Swelling of the human cornea revealed by high-speed, ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4579–4584. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abou Shousha M, Yoo SH, Sayed MS, et al. In Vivo Characteristics of Corneal Endothelium/Descemet’s membrane Complex for the Diagnosis of Corneal Graft Rejection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;178:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavelka M, Roth J. Functional Ultrastructure: Atlas of Tissue Biology and Pathology. Vienna: Springer Vienna; 2015. Descemet’s Membrane; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurz GH, D’Amico RA. Histopathology of corneal graft failures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;66:184–199. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(68)92063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]