Abstract

Expression of the immune-checkpoint ligand CD274 (programmed cell death 1 ligand 1, PD-L1, from gene CD274) contributes to suppression of antitumor T cell–mediated immune response in various tumor types. However, the role of PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2, CD273, from gene PDCD1LG2) in the tumor microenvironment remains unclear. We hypothesized that tumor PDCD1LG2 expression might be inversely associated with lymphocytic reactions to colorectal cancer. We examined tumor PDCD1LG2 expression by immunohistochemistry in 823 colon and rectal carcinoma cases within two U.S.-nationwide cohort studies and categorized tumors into quartiles according to the percentage of PDCD1LG2–expressing carcinoma cells. We conducted multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis to assess the associations of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression with Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, intratumoral periglandular reaction, or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, controlling for potential confounders, including microsatellite instability, CpG island methylator phenotype, long-interspersed nucleotide element-1 methylation, and KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations. Tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was inversely associated with Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction (Ptrend = 0.0003). For a unit increase in the three-tiered ordinal categories of Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, a multivariable odds ratio in the highest (vs lowest) quartile of the percentage of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells was 0.38 (95% confidence interval, 0.22–0.67). Tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was not associated with peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, intratumoral periglandular reaction, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, or patient survival (Ptrend>0.13). Thus, tumor PDCD1LG2 expression is inversely associated with Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction to colorectal cancer, suggesting a possible role of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells in inhibiting the development of tertiary lymphoid tissues during colorectal carcinogenesis.

Keywords: adenocarcinoma, colorectum, immunoprevention, immunotherapy, molecular pathology

Introduction

Immunotherapy has emerged as a promising strategy for cancer treatment (1). Studies suggest that tumor expression of immune checkpoint ligands triggers the transient downregulation of T-cell activity at the tumor-immune interface, leading to immune evasion (1). Therapeutic antibodies targeting the immune checkpoint receptor PDCD1 (programmed cell death 1, PD-1, from gene PDCD1) and its ligand, CD274 (PDCD1 ligand 1, PD-L1, from gene CD274), are effective for treatment of various types of tumors (1,2). However, the clinical efficacy of these checkpoint blockade immunotherapies vary by tumor type, tumor molecular characteristics, and immune-cell infiltrates, in addition to aberrant expression of immune-checkpoint ligands in the tumor microenvironment (2–6).

Colorectal carcinogenesis involves a heterogeneous oncogenic process influenced by differing sets of genetic and epigenetic alterations, diet, microbiota, and host immunity (7–10). Potent lymphocytic reactions and higher density of T cells in colorectal carcinoma tissue have been associated with better patient survival, supporting a major role of antitumor immunity in inhibiting tumor progression (11–16). Previous studies have linked intense lymphocytic reaction to colorectal cancer to high tumor neoantigen load and certain tumor molecular characteristics, including high-level microsatellite instability (MSI-high) (15–18). Evidence attests to the important role of CD274 (PD-L1) in suppressing antitumor immunity in a number of tumor types including colorectal cancer (1–3). PDCD1LG2 (PDCD1 ligand 2, PD-L2, from gene PDCD1LG2) is implicated in inducing immune tolerance under physiological and pathological conditions (1,19–21); however, the potential role of PDCD1LG2 in the tumor microenvironment remains poorly understood. We hypothesized that tumor PDCD1LG2 expression might be inversely associated with lymphocytic reaction to colorectal cancer.

To test this hypothesis, we utilized colorectal carcinoma cases identified in two U.S.-nationwide prospective cohort studies and examined tumor PDCD1LG2 expression in relation to four histological patterns of lymphocytic reactions: Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, intratumoral periglandular reaction, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). Our comprehensive database integrating tumor immunity data with relevant clinical, pathological, and tumor molecular information enabled us to investigate the independent association of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression with lymphocytic reactions to colorectal cancer, controlling for potential confounders. In addition, as a secondary exploratory analysis, we assessed the prognostic value of PDCD1LG2 expression in colorectal carcinoma.

Materials and Methods

Study populations and histopathologic features

We utilized two prospective cohort studies: the Nurses’ Health Study (121,701 women followed since 1976) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (51,529 men followed since 1986) (22). Participants have been sent follow-up questionnaires biennially to collect updated information on lifestyle factors and to identify newly diagnosed diseases including colorectal cancers. The National Death Index was used to ascertain deaths of study participants and to identify unreported lethal colorectal cancer cases. Study physicians reviewed medical records of colorectal cancer patients to extract clinical information, including the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, tumor location, and recorded cause of death in deceased individuals. Patients were followed until death or January 2012, whichever came first. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks were collected from hospitals across the U.S. where participants with colorectal cancer had undergone tumor resection. The study pathologist (S.O.), who was blinded to other data, performed centralized pathology review, and recorded histopathological features. Tumor differentiation was defined as well-to-moderate (>50% glandular area) or poor (≤50% glandular area). Four histological patterns of lymphocytic reactions –Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, intratumoral periglandular reaction, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) – were scored as 0, 1, 2, or 3 by a pathologist (S.O.), as previously described (16). Because of the limited numbers of cases with scores of 2 and 3 in each lymphocytic reaction pattern, we categorized lymphocytic reaction patterns as negative/low (score 0), intermediate (score 1), or high (scores 2–3), as previously described (16,23). Crohn’s-like lymphoid reactions were defined as a transmural lymphoid reaction across the full-thickness of the bowel wall (16). A peritumoral lymphocytic reaction was defined as discrete lymphoid reactions surrounding tumors (16). An intratumoral periglandular reaction was defined as lymphocytic reactions in tumor stroma within the tumor mass (16). TILs were defined as lymphocytes on top of tumor cells in tissue sections (16). An agreement study on the four lymphocytic reaction patterns that encompassed more than 400 tumors was performed, and we observed a good concordance between independent reviews by two pathologists (S.O. and J. Glickman) (16). The overall lymphocytic reaction score (ranging from 0 to 12) was calculated as the sum of scores for the four patterns of histological lymphocytic reaction, as previously described (16). Of the 1,546 colon and rectal carcinomas diagnosed by 2008 that had available tumor FFPE blocks, we constructed tissue microarrays (TMA) from 1,014 cases (24). When constructing TMA blocks, we punched tumor areas, including tumor center and tumor margin, to select up to four 0.6-mm tissue cores from each tumor, considering spacial heterogeneity. We excluded 191 cases, in which PDCD1LG2 expression was unevaluable due to core exhaustion, detachment of cores during staining procedure, or insufficient staining quality. Consequently, we analyzed a total of 823 colorectal carcinoma cases with available PDCD1LG2 protein expression data (Supplementary Fig. S1). Tissue collection and analyses were approved by the human subjects committee at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Immunohistochemistry

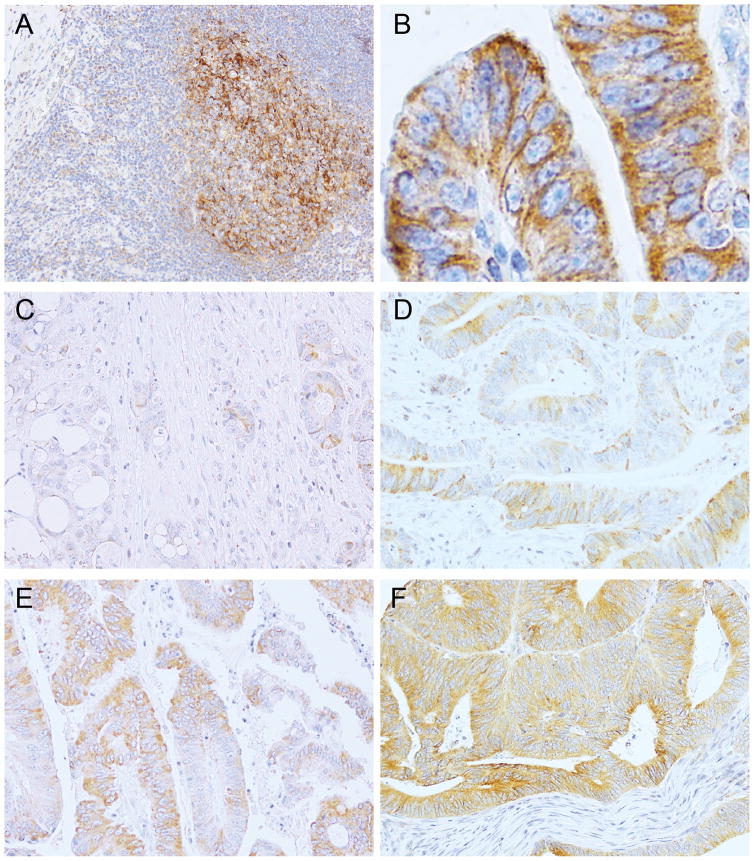

For PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2) immunohistochemistry, we utilized an automated staining system (Bond III, Leica Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s protocols, with the use of a monoclonal antibody to PDCD1LG2 that was generated in the laboratory of G.J.F. (clone 366C.9E5; mouse IgG1 kappa; dilution, 1:6000) (25–28). Pre-baked sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and incubated in ER2 solution (pH8; Leica Biosystems) for 30 min. Slides were incubated with anti-PDCD1LG2 for a total of 2 h with two separate applications, followed by 8 min of post-primary blocking reagent, 12 min of horseradish peroxidase-labeled polymer, 5 min of peroxidase block, and 15 min of DAB developing. All reagents were components of the Bond Polymer Refine Detection system (Leica Biosystems; catalog number, DS9800). Slides were then counterstained by hematoxylin for 5 minutes. The positive control for PDCD1LG2 immunohistochemistry was human tonsil and colorectum, in which we observed positive staining on immune cells, including dendritic cells in germinal centers within mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues and Crohn’s-like lymphoid reactions (Fig. 1A). Smooth muscle cells in these human specimens served as internal negative controls. To control for potential nonspecific binding of anti-PDCD1LG2, we used an an isotype-identical antibody (clone DAK-GO1; mouse IgG1 kappa; dilution, 1:6000; Agilent, catalog number, X0931) with replacement of primary anti-PDCD1LG2 in the same immunohistochemical assay, which yielded negative staining (Supplementary Fig. S2). Immunohistochemical expression of PDCD1LG2 was interpreted by a pathologist (Y.M.) unaware of other data. PDCD1LG2 expression was observed in the cytoplasm and on the membrane of colorectal carcinoma cells (Fig. 1B). We recorded the percentage of PDCD1LG2+ carcinoma cells in the cytoplasm and/or membrane (range, 0 to 100; mean, 55; median, 60; and interquartile range, 20 to 80), and categorized tumors into quartiles according to the percentage of PDCD1LG2-expressing tumor cells either in the cytoplasm or on the membrane (Fig. 1C–F). A subset of colorectal cancer cases (n = 142) was examined independently by a second pathologist (A.dS.), and the concordance between the two observers was reasonable with a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.74 (P < 0.0001; for the percentage of positive-staining tumor cells) and a weighted κ of 0.62 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.53–0.72; for quartile categories of the percentage of positive-staining tumor cells]. PDCD1LG2 expression on stromal cells, including immune cells, was evaluated based on the presence or absence of cytoplasmic and/or membrane staining in stromal cells within tumor tissues. We examined CD274 (PD-L1) expression by immunohistochemistry and categorized tumor CD274 expression as low or high, as previously described (29,30). Immunostaining for CD3, CD8, CD45RO (from gene PTPRC), and FOXP3, was conducted and the density of T cells in tumor tissue measured with the Ariol image analysis system (Genetix), as previously described (14,31).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry for PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2) in human tonsil (A) and colorectal carcinoma tissue (B–F). A strong expression of PDCD1LG2 is observed on immune cells, including dendritic cells in a germinal center, which served as positive controls (A). PDCD1LG2 expression is observed in the cytoplasm and on the membrane of colorectal carcinoma cells (B). Examples of PDCD1LG2 immunostaining in each quartile category of fraction of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells are shown [quartile 1 (C), quartile 2 (D), quartile 3 (E), and quartile 4 (F)].

DNA analyses

DNA was extracted from archival colorectal cancer tissue blocks. MSI status was analyzed with the use of 10 microsatellite markers (BAT25, BAT26, BAT40, D2S123, D5S346, D17S250, D18S55, D18S56, D18S67, and D18S487), as previously described (22). We defined MSI-high as the presence of instability in ≥30% of the markers, and non-MSI-high as instability in <30% of the markers (22). Methylation analyses for eight promoters specific for the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP; CACNA1G, CDKN2A, CRABP1, IGF2, MLH1, NEUROG1, RUNX3, and SOCS1) were conducted using bisulfite-treated DNA and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as previously described (22). CIMP-high, CIMP-low, and CIMP-negative were defined as ≥6/8, 1/8–5/8, and 0/8 methylated promoters, respectively, according to the previously-established criteria (22). Long-interspersed nucleotide element-1 (LINE-1) methylation was determined using bisulfite modification of DNA followed by PCR and pyrosequencing (22). PCR and pyrosequencing were performed for BRAF (codon 600), KRAS (codons 12, 13, 61, and 146), and PIK3CA (exons 9 and 20) (22). We performed quantitative PCR to measure the amount of Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum) DNA in tumor tissue, as previously described (32). We categorized colorectal carcinoma cases with detectable F. nucleatum DNA as low or high, using the median as the cut point amount among F. nucleatum-positive carcinomas (32).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute) and all P values were two-sided. Our primary hypothesis testing was an assessment of the associations of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression (as a quartile predictor variable) with the four histological patterns of lymphocytic reaction (Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, intratumoral periglandular reaction, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes) as outcome variables. Because we examined the four outcome lymphocytic reaction variables, we adjusted the two-sided α level to 0.01 (≈ 0.05/4) by Bonferroni correction for multiple hypothesis testing.

We performed multivariable logistic regression analysis to control for potential confounders. The multivariable model initially included age at diagnosis (continuous), sex (female vs male), year of diagnosis (continuous), family history of colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative [present vs absent vs missing (1.3% missing)], tumor location [proximal colon vs distal colon vs rectum vs missing (0.5% missing)], MSI status [MSI-high vs non-MSI-high vs missing (2.9% missing)], CIMP status [high vs low/negative vs missing (7.9% missing)], BRAF mutation [mutant vs wild-type vs missing (2.2% missing)], KRAS mutation [mutant vs wild-type vs missing (2.7% missing)], PIK3CA mutation [mutant vs wild-type vs missing (8.6% missing)], and LINE-1 methylation level (continuous). For the cases with missing data on LINE-1 methylation (2.7% missing), we assigned a separate indicator variable. A backward elimination with a threshold of P = 0.05 was used to select covariates for the final model. For cases with missing information in any of the categorical variables, we included those cases in the majority category of a given covariate to limit the degrees of freedom of the final models. We confirmed that excluding the cases with missing information in any of the covariates did not substantially alter results through sensitivity analyses (data not shown). We assessed the proportional odds assumption in an ordinal logistic regression model, which was generally satisfied (P > 0.05).

To assess associations between tumor PDCD1LG2 expression and other categorical variables, the chi-square test was performed. To compare mean age and mean LINE-1 methylation levels, an analysis of variance assuming equal variances was performed. All of those cross-sectional analyses for clinical, pathological, and molecular associations were secondary exploratory analyses, with adjusted two-sided α level of 0.003 (≈ 0.05/15) for multiple hypothesis testing.

We conducted Kaplan-Meier analysis to compare survival between patient groups. Deaths from causes other than colorectal cancer were censored in colorectal cancer-specific mortality analyses. To adjust for confounding, we performed Cox proportional hazards regression analysis and calculated hazard ratio for mortality. The multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models initially included disease stage (I/II vs III/IV/unknown) in addition to the same set of variables as in the aforementioned initial multivariable logistic regression analysis. We performed a backward elimination with a threshold of P = 0.05 to select variables for the final multivariable model. To limit the degrees of freedom of the models, we included cases with missing information in a categorical covariate in the majority category. For the cases missing data on LINE-1 methylation, we assigned a separate indicator variable. We confirmed that excluding the cases with missing data in any of the covariates did not materially alter results (data not shown). The proportionality of hazards assumption was satisfied (P > 0.05) by evaluating time-dependent variables, which were the cross-product of the PDCD1LG2 expression variable and survival time.

Results

We examined tumor expression of PDCD1LG2 (PD-LG2) by immunohistochemistry in 823 colorectal carcinoma cases within the two U.S-nationwide cohort studies (Fig. 1). Tumors were categorized into quartiles according to the percentage of PDCD1LG2-expressing carcinoma cells (median, 60%; interquartile range, 20% to 80%). Clinical, pathological, and molecular characteristics according to tumor PDCD1LG2 expression in colorectal cancer are summarized in Table 1. Higher fractions of PDCD1LG2-expressing tumor cells were associated with female (P = 0.0001), well to moderate tumor differentiation (P = 0.001), and a high level of tumor CD274 (PD-L1) expression (P = 0.001). We performed multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis to assess relationships of sex (as a predictor variable) and tumor PDCD1LG2 expression (as an outcome variable), and found that female gender remained significantly associated with PDCD1LG2 expression (for a unit increase of quartile categories of PDCD1LG2 expression; odds ratio [OR], 1.68; 95% CI, 1.29–2.18; P=0.0001; Supplementary Table S1). There was a trend towards higher tumor PDCD1LG2 expression associated with LINE-1 hypomethylation (OR for 30% decrease in methylation level, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.11–2.44; P = 0.013 with the adjusted α level of 0.004; Supplementary Table S1). Tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was not significantly associated with the other characteristics examined (P > 0.03; with the adjusted α level of 0.003; Table 1). PDCD1LG2–expressing stromal cells, including immune cells, were found in 630 (78%) of 810 cases. The presence of PDCD1LG2–expressing stromal cells was not significantly associated with any clinical, pathological, or molecular features (P > 0.007; with the adjusted α level of 0.003; Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1.

Clinical, pathological, and molecular features according to tumor PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2) expression in 823 colorectal cancer cases

| Characteristic† | Total No. (n=823) | Fraction of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells (quartile)* | P value‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 0–20%, Quartile 1 (n=210) | 21–50%, Quartile 2 (n=187) | 51–80%, Quartile 3 (n=247) | 81–100%, Quartile 4 (n=179) | |||

| Mean age±SD (yr) | 68.7±9.0 | 68.1±9.1 | 68.8±10.1 | 69.3±8.7 | 68.5±8.1 | 0.60 |

| Sex | 0.0001 | |||||

| Men | 364 (44%) | 98 (47%) | 96 (51%) | 117 (47%) | 53 (30%) | |

| Women | 459 (56%) | 112 (53%) | 91 (49%) | 130 (53%) | 126 (70%) | |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.66 | |||||

| Prior to 1996 | 272 (33%) | 76 (36%) | 59 (32%) | 77 (31%) | 60 (34%) | |

| 1996 to 2000 | 284 (35%) | 62 (30%) | 72 (39%) | 88 (36%) | 62 (35%) | |

| 2001 to 2008 | 267 (32%) | 72 (34%) | 56 (30%) | 82 (33%) | 57 (32%) | |

| Family history of colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative | 0.58 | |||||

| Absent | 642 (79%) | 164 (80%) | 138 (75%) | 196 (80%) | 144 (80%) | |

| Present | 170 (21%) | 42 (20%) | 45 (25%) | 48 (20%) | 35 (20%) | |

| Tumor location | 0.040 | |||||

| Cecum | 146 (18%) | 45 (22%) | 40 (22%) | 39 (16%) | 22 (12%) | |

| Ascending to transverse colon | 260 (32%) | 68 (33%) | 58 (31%) | 67 (27%) | 67 (38%) | |

| Splenic flexure to sigmoid | 249 (30%) | 56 (27%) | 46 (25%) | 90 (36%) | 57 (32%) | |

| Rectosigmoid and rectum | 164 (20%) | 40 (19%) | 42 (23%) | 51 (21%) | 31 (18%) | |

| Disease stage | 0.39 | |||||

| I | 171 (23%) | 39 (21%) | 42 (24%) | 50 (22%) | 40 (24%) | |

| II | 250 (33%) | 61 (33%) | 63 (37%) | 78 (34%) | 48 (29%) | |

| III | 216 (29%) | 54 (29%) | 44 (26%) | 74 (32%) | 44 (26%) | |

| IV | 120 (16%) | 33 (18%) | 23 (13%) | 29 (13%) | 35 (21%) | |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.001 | |||||

| Well to moderate | 746 (91%) | 177 (84%) | 171 (92%) | 234 (95%) | 164 (92%) | |

| Poor | 75 (9%) | 33 (16%) | 14 (8%) | 13 (5%) | 15 (8%) | |

| MSI status | 0.86 | |||||

| Non-MSI-high | 663 (83%) | 167 (82%) | 149 (82%) | 203 (84%) | 144 (85%) | |

| MSI-high | 136 (17%) | 37 (18%) | 33 (18%) | 40 (16%) | 26 (15%) | |

| CIMP status | 0.047 | |||||

| Low/negative | 627 (83%) | 154 (79%) | 141 (82%) | 183 (81%) | 149 (90%) | |

| High | 131 (17%) | 40 (21%) | 30 (18%) | 44 (19%) | 17 (10%) | |

| BRAF mutation | 0.52 | |||||

| Wild-type | 686 (85%) | 171 (83%) | 161 (88%) | 208 (84%) | 146 (85%) | |

| Mutant | 119 (15%) | 34 (17%) | 21 (12%) | 39 (16%) | 25 (15%) | |

| KRAS mutation | 0.27 | |||||

| Wild-type | 474 (59%) | 111 (55%) | 117 (65%) | 145 (59%) | 101 (59%) | |

| Mutant | 327 (41%) | 92 (45%) | 64 (35%) | 100 (41%) | 71 (41%) | |

| PIK3CA mutation | 0.43 | |||||

| Wild-type | 639 (85%) | 150 (83%) | 154 (88%) | 204 (86%) | 131 (82%) | |

| Mutant | 113 (15%) | 31 (17%) | 22 (13%) | 32 (14%) | 28 (18%) | |

| Mean LINE-1 methylation level±SD (%) | 62.2±9.7 | 63.5±9.9 | 61.9±9.7 | 61.7±9.9 | 61.6±8.9 | 0.15 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum DNA | 0.44 | |||||

| Negative | 574 (87%) | 139 (85%) | 129 (85%) | 183 (89%) | 123 (89%) | |

| Low | 42 (6%) | 15 (9%) | 8 (5%) | 12 (6%) | 7 (5%) | |

| High | 42 (6%) | 10 (6%) | 14 (9%) | 10 (5%) | 8 (6%) | |

| Tumor CD274 (PD-L1) expression level | 0.001 | |||||

| Low | 296 (38%) | 84 (44%) | 80 (45%) | 86 (36%) | 46 (27%) | |

| High | 478 (62%) | 106 (56%) | 98 (55%) | 150 (64%) | 124 (73%) | |

Abbreviations: CIMP, CpG island methylator phenotype; LINE-1, long interspersed nucleotide element-1; MSI, microsatellite instability; SD, standard deviation.

Tumors were categorized into quartiles according to the percentage of PDCD1LG2-expressing carcinoma cells (quartile 1, 0–20%; quartile 2, 21–50%; quartile 3, 51–80%; quartile 4, 81–100%).

Percentage indicates the proportion of cases with a specific clinical, pathological, or molecular feature in colorectal cancer cases with each quartile category of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression.

To assess associations between the quartile categories of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression and categorical data, the chi-square test was performed.

To compare mean age and mean LINE-1 methylation, an analysis of variance was performed. We adjusted two-sided α level to 0.003 (≈ 0.05/15) by simple Bonferroni correction for multiple hypothesis testing.

Table 2 shows the distribution of colorectal cancer cases according to tumor PDCD1LG2 expression and the four histological patterns of lymphocytic reaction. Tumor PDCD1LG2 expression correlated inversely with Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction (P = 0.0002, by Spearman correlation test). In our primary hypothesis testing, we used ordinal logistic regression analysis to assess the association of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression (an ordinal quartile predictor variable [1 to 4]) with Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, intratumoral periglandular reaction, or TILs as an outcome variable (ordinal 3-tiered; negative/low, intermediate, and high; Table 3 and Supplementary Table S3). Tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was inversely associated with Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction in the univariable and multivariable ordinal logistic regression analyses (Ptrend < 0.0004). For a unit increase in the ordinal categories of Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, a multivariable OR in the highest (vs lowest) quartile of the percentage of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.22–0.67). We did not observe any statistically significant association of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression with peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, intratumoral periglandular reaction, or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (Ptrend > 0.06; with the adjusted α level of 0.01). In addition, we found an inverse correlation between tumor PDCD1LG2 expression and the overall lymphocytic reaction score (Spearman correlation coefficient r = −0.11, P = 0.006; Supplementary Table S4). In a multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis, tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was not significantly associated with the overall lymphocytic reaction score (Ptrend = 0.046, with the adjusted α level of 0.01; Supplementary Table S5). As an exploratory analysis, we conducted Spearman correlation tests to assess the associations of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression [ordinal quartile categories (1 to 4)] with CD3+ cell, CD8+ cell, PTPRC (CD45RO)+ cell, and FOXP3+ cell densities (cells/mm2; continuous variables) in tumor tissue, and found only weak correlations [Spearman correlation coefficient r < 0.25 (0.24 for CD3+ cell, 0.13 for CD8+ cell, 0.12 for PTPRC+ cell, and 0.06 for FOXP3+ cell)].

Table 2.

Distribution of colorectal cancer cases according to tumor PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2) expression and histological lymphocytic reaction patterns

| Fraction of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells (quartile)* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Total No. | 0–20%, Quartile 1 | 21–50%, Quartile 2 | 51–80%, Quartile 3 | 81–100%, Quartile 4 | P value† | |

| Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction (n = 680) | 0.0002 | |||||

| Negative/low | 505 (74%) | 121 (66%) | 105 (71%) | 151 (76%) | 128 (84%) | |

| Intermediate | 127 (19%) | 42 (23%) | 31 (21%) | 39 (20%) | 15 (10%) | |

| High | 48 (7%) | 19 (10%) | 11 (7%) | 9 (5%) | 9 (6%) | |

| Peritumoral lymphocytic reaction (n = 811) | 0.80 | |||||

| Negative/low | 118 (15%) | 32 (15%) | 24 (13%) | 31 (13%) | 31 (18%) | |

| Intermediate | 573 (71%) | 145 (70%) | 132 (71%) | 178 (74%) | 118 (67%) | |

| High | 120 (15%) | 30 (14%) | 30 (16%) | 32 (13%) | 28 (16%) | |

| Intratumoral periglandular reaction (n = 813) | 0.10 | |||||

| Negative/low | 102 (13%) | 24 (12%) | 16 (9%) | 30 (12%) | 32 (18%) | |

| Intermediate | 618 (76%) | 160 (77%) | 146 (78%) | 186 (77%) | 126 (71%) | |

| High | 93 (11%) | 23 (11%) | 25 (13%) | 26 (11%) | 19 (11%) | |

| Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (n = 812) | 0.07 | |||||

| Negative/low | 594 (73%) | 149 (72%) | 128 (69%) | 177 (73%) | 140 (79%) | |

| Intermediate | 128 (16%) | 33 (16%) | 30 (16%) | 42 (17%) | 23 (13%) | |

| High | 90 (11%) | 25 (12%) | 28 (15%) | 23 (10%) | 14 (8%) | |

Tumors were categorized into quartiles according to the percentage of PDCD1LG2–expressing carcinoma cells (quartile 1, 0–20%; quartile 2, 21–50%; quartile 3, 51–80%; quartile 4, 81–100%).

P value was calculated by Spearman correlation test between tumor PDCD1LG2 expression (ordinal quartile categories; 1 to 4) and each histological pattern of lymphocytic reaction (ordinal categories; negative/low, intermediate, and high).

Because we assessed four primary outcome variables, we adjusted two-sided α level to 0.01 (≈ 0.05/4) by simple Bonferroni correction.

Table 3.

Ordinal logistic regression analysis to assess the association of tumor PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2) expression (predictor) with histological lymphocytic reaction (outcome)

| Univariable OR (95% CI) | Multivariable OR (95% CI)† | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model for Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction as an ordinal outcome variable (n = 680) | |||

| Fraction of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells (quartile)* | Quartile 1 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 0.78 (0.49–1.24) | 0.79 (0.48–1.30) | |

| Quartile 3 | 0.61 (0.39–0.95) | 0.58 (0.36–0.93) | |

| Quartile 4 | 0.38 (0.22–0.64) | 0.38 (0.22–0.67) | |

| Ptrend‡ | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | |

| Model for peritumoral lymphocytic reaction as an ordinal outcome variable (n = 811) | |||

| Fraction of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells (quartile)* | Quartile 1 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 1.18 (0.77–1.82) | 1.20 (0.78–1.85) | |

| Quartile 3 | 1.06 (0.71–1.58) | 1.09 (0.73–1.64) | |

| Quartile 4 | 0.97 (0.63–1.50) | 1.01 (0.65–1.57) | |

| Ptrend‡ | 0.81 | 0.98 | |

| Model for intratumoral periglandular reaction as an ordinal outcome variable (n = 813) | |||

| Fraction of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells (quartile)* | Quartile 1 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 1.28 (0.81–2.04) | 1.32 (0.83–2.11) | |

| Quartile 3 | 0.95 (0.61–1.46) | 0.99 (0.64–1.53) | |

| Quartile 4 | 0.72 (0.45–1.14) | 0.75 (0.47–1.20) | |

| Ptrend‡ | 0.10 | 0.16 | |

| Model for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes as an ordinal outcome variable (n = 812) | |||

| Fraction of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells (quartile)* | Quartile 1 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 1.19 (1.78–1.82) | 1.34 (0.84–2.13) | |

| Quartile 3 | 0.92 (0.61–1.39) | 0.92 (0.58–1.44) | |

| Quartile 4 | 0.67 (0.42–1.07) | 0.81 (0.49–1.35) | |

| Ptrend‡ | 0.07 | 0.23 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Tumors were categorized into quartiles according to the percentage of PDCD1LG2–expressing carcinoma cells (quartile 1, 0–20%; quartile 2, 21–50%; quartile 3, 51–80%; quartile 4, 81–100%).

The multivariable ordinal logistic regression analysis model initially included age, sex, year of diagnosis, family history of colorectal carcinoma in any parent or sibling, tumor location, microsatellite instability, CpG island methylator phenotype, KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations, and long interspersed nucleotide element-1 methylation level.

A backward elimination with a threshold of P = 0.05 was used to select variables in the final models. Variables remaining in the final multivariable model for Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction were shown in Supplementary Table S3.

Ptrend value was calculated by the linear trend across the ordinal quartile categories of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression (1 to 4; as a predictor variable) in the ordinal logistic regression model for each histological pattern of lymphocytic reaction (negative/low, intermediate, and high; as an ordinal outcome variable).

Because we assessed four primary outcome variables, we adjusted two-sided α level to 0.01 (≈ 0.05/4) by simple Bonferroni correction.

As a secondary analysis, we conducted Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to examine a prognostic role of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression in colorectal cancer. No statistically significant association between tumor PDCD1LG2 expression and colorectal cancer-specific or overall mortality (Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. S3) was observed. In addition, we conducted multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses, and found that stronger Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction was associated with favorable patient outcome in our current dataset (Ptrend = 0.0005 for colorectal cancer-specific mortality, Ptrend < 0.0001 for overall mortality; Supplementary Table S6).

Table 4.

Tumor PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2) expression and colorectal cancer mortality

| Fraction of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells* | Total No. | Colorectal cancer-specific mortality | Overall mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| No. of events | Univariable HR (95% CI) | Multivariable HR (95% CI)† | No. of events | Univariable HR (95% CI) | Multivariable HR (95% CI)† | ||

|

|

|

||||||

| Quartile 1 | 207 | 71 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 122 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 185 | 58 | 0.87 (0.61–1.23) | 0.99 (0.70–1.41) | 106 | 0.93 (0.71–1.20) | 1.03 (0.79–1.34) |

| Quartile 3 | 246 | 63 | 0.70 (0.50–0.98) | 0.68 (0.48–0.95) | 130 | 0.85 (0.67–1.09) | 0.84 (0.65–1.07) |

| Quartile 4 | 179 | 59 | 0.92 (0.65–1.31) | 0.95 (0.67–1.34) | 95 | 0.85 (0.65–1.11) | 0.88 (0.67–1.15) |

| Ptrend‡ | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.14 | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard risk.

Tumors were categorized into quartiles according to the percentage of PDCD1LG2–expressing carcinoma cells (quartile 1, 0–20%; quartile 2, 21–50%; quartile 3, 51–80%; quartile 4, 81–100%).

The multivariable Cox regression model initially included age, sex, year of diagnosis, family history of colorectal carcinoma in any parent or sibling, tumor location, disease stage, microsatellite instability, CpG island methylator phenotype, KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations, and long interspersed nucleotide element-1 methylation level.

A backward elimination with a threshold of P=0.05 was used to select variables in the final models.

Ptrend value was calculated across the ordinal quartile categories of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression (1 to 4) as a continuous variable in the Cox regression models.

Discussion

In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that tumor PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2) expression might be inversely associated with lymphocytic reactions to colorectal cancer. We found an inverse association between tumor PDCD1LG2 expression and Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, independent of potential confounders, including MSI status, CIMP status, and LINE-1 methylation; these specific tumor molecular characteristics have been associated with the abundance of lymphocytic infiltration in colorectal carcinoma tissue (16). Our results suggest a possible role of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells in suppression of antitumor immune responses to colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer represents a heterogeneous group of tumors that results from not only progressive accumulations of differing sets of somatic molecular alterations, but also various host-tumor interactions including antitumor immunity (33–35). The assessment of host immunity against colorectal cancer in the tumor microenvironment is increasingly important in translational research and routine clinical practice for tumor classification (36,37). A strong histological lymphocytic reaction to colorectal carcinoma has been associated with better patient survival (15,16). These data indicate that histopathological characterization of lymphocytic infiltrates in cancer tissue is of value when assessing the magnitude of antitumor immune response to colorectal malignancies.

We found that tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was inversely associated with Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, but not with peritumoral lymphocytic reaction, intratumoral periglandular reaction, or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, suggesting the unique immunological nature of Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction. Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction is characterized by the transmural presence of discrete lymphocytic aggregates with tertiary lymphoid structures, including germinal centers, T-cell-rich area, and high endothelial venules (38–40). Previous studies have linked strong Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction to favorable outcomes in patients with colorectal carcinoma (15,16,38,39). Tertiary lymphoid tissues, such as Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, has a potential role in maintaining adaptive immune responses to colorectal cancer, as a local source of antigen-specific effector B and T cells (39,40). Although the precise role of PDCD1LG2 in the tumor microenvironment remains to be investigated, PDCD1LG2 appears to be important in modulation of type 2 helper T (Th2) cell immune responses under physiological and pathological conditions (19). It is possible that PDCD1LG2 may inhibit functional activities of Th2 cells, such as precursors of follicular helper T cells that are responsible for the formation of germinal centers (41), in the tumor microenvironment, leading to downregulation of Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction against colorectal carcinoma.

The colocalization between PDCD1 (PD-1)–expressing cells and T-cell infiltrates has been reported in various solid tumors (2,42). A study on several tumor types, including colorectal cancer, have demonstrated strong positive correlations of PDCD1LG2 and CD274 with the IFNG (interferon-γ)– and CD8-signaling pathways (21). In the tumor microenvironment, PDCD1LG2 can be induced by several proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFNG, IL4, and CSF2 (colony stimulating factor 2), that can be produced by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, CD4+ type 1 helper T (Th1) cells, CD4+ Th2 cells, and macrophages (1,2). Although we observed a positive association of PDCD1LG2 expression with CD274 (PD-L1) expression or CD3+ cell density in tumor tissues, we recognize the limitations of TMA-based singleplex immunohistochemistry in the assessment of spatial relationships of PDCD1LG2–expressing cells or CD274–expressing cells with various subpopulations of immune cells. Future studies utilizing multiplex immunohistochemistry of whole tissue sections assisted with digital image analysis system would likely unveil the possible spatial associations of the two PDCD1 ligands with specific immune-cell fractions.

PDCD1LG2 expression is commonly observed in dendritic cells and macrophages within secondary and tertiary lymphoid organs throughout the body, whereas CD274 is more broadly expressed on antigen-presenting cells and other hematopoietic cell types (1,19,43), suggesting differing functional roles of the two PDCD1 ligands in the immunomodulation of host immunity. PDCD1LG2 and CD274 can be expressed in stromal cells, including immune cells, within tumor tissues of various tumor types (18,42,43), which is consistent with our previous (29) and current findings on colorectal cancer. In the tumor microenvironment, PDCD1LG2 and CD274 may be induced in a variety of immune and nonimmune cells by the adaptive mechanism, depending on the milieu of inflammatory cytokines (1,2). These lines of evidence, together with our findings, underscore the complex interactions between neoplastic and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment.

Our data suggesting an association of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression with female gender are intriguing. Female gender was associated with increased PDCD1LG2 expression in a study of hematopoietic neoplasms (44), similar to our findings in colorectal carcinoma. Sex hormones, such as estrogens, may upregulate cellular expression of immune checkpoint molecules, including the PDCD1 and its ligand CD274, in a variety of cell types (45,46). Taken together, our population-based data will likely inform further mechanistic studies to clarify potential roles of female sex hormones in the regulation of the immune checkpoint pathway in the tumor microenvironment.

In our population-based data, we found a trend towards higher tumor PDCD1LG2 expression associated with LINE-1 hypomethylation, though not statistically significant at the α level after adjusting for multiple hypothesis testing. FOXP3+ cell density in colorectal cancer tissue, which has been inversely associated with tumor CD274 expression (29), was not correlated with PDCD1LG2 expression in the current analysis, suggesting a differential influence of the two PDCD1 ligands on regulatory T cells in colorectal cancer microenvironments.

In our exploratory analysis, tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was not significantly associated with colorectal cancer mortality, consistent with a study using gene expression data on PDCD1LG2 from a colonic adenocarcinoma cohort in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset (21). Whereas one study showed that PDCD1LG2 expression in esophageal cancer was associated with poor prognosis, studies on other tumor types such as pancreatic carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and ovarian carcinoma did not show a prognostic role of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression (19,47). Further studies are needed to determine the prognostic role of PDCD1LG2 expression in different types of malignant tumors.

One study reported that not only CD274, but also PDCD1LG2, status were useful for predicting clinical response to pembrolizumab [monoclonal antibody (mAb) to PDCD1] in patients with head and neck carcinoma (43). Although tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was not significantly associated with colorectal cancer survival in our current study, tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was inversely associated with Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction, the latter of which has been an important arm of the adaptive immune response in colorectal carcinogenesis. Therefore, immunotherapy strategies that block the PDCD1LG2/PDCD1 axis may prolong patient survival through reactivation of antitumor immunity, and our current findings may have clinical implications.

We recognize limitations of the current study. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study makes it challenging to determine the causal relationship between PDCD1LG2 expression and Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction. Nonetheless, our specific hypothesis is based on several lines of evidence indicating that PDCD1LG2 checkpoint ligand expression contributes to suppression of T cell–mediated immune reaction (1,2,19,20,28,43). Another limitation is the lack of standardized antibody and evaluation methods for PDCD1LG2 immunohistochemistry in FFPE tissues. We used the automated immunostaining system as well as the established mAb to PDCD1LG2 that has been validated in previous studies (25–28). Considering the binding activity of the PDCD1LG2 ligand to its cognate cell surface receptors on immune cells, a fraction of tumor cells with PDCD1LG2 expression on the cell surface membrane is likely important. However, membranous PDCD1LG2 staining was considerably masked by cytoplasmic staining, which likely caused an underestimation of membrane PDCD1LG2 expression, and limited its reproducibility when assayed. Hence, we assessed fractions of tumor cells that expressed PDCD1LG2 in the cytoplasm and/or membrane, which is a method similar to that in the previous studies on solid tumors (27,28). A blinded and independent assessment of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression was performed, and we confirmed substantial interobserver agreement between the two pathologists. Despite limitations of immunohistochemical evaluation for PDCD1LG2 expression, we could demonstrate a significant and strong inverse association between tumor PDCD1LG2 expression and Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction.

Strengths of our current study include the use of our molecular pathological epidemiology (48) database of a large number of colorectal carcinoma cases in the two independent prospective cohort studies, which integrates clinicopathological features, major tumor molecular features, and tumor immunity status in colorectal cancer tissue. Our study design (49,50) and population-based database allowed us to rigorously investigate the association of tumor PDCD1LG2 expression with lymphocytic reaction to colorectal cancer, controlling for multiple potential confounders. In addition, our colorectal cancer specimens were collected from a large number of hospitals in diverse settings across the U.S., which increases the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, we have shown that tumor PDCD1LG2 expression is inversely associated with Crohn’s-like lymphoid reactions to colorectal carcinoma, suggesting a possible influence of PDCD1LG2–expressing tumor cells on adaptive antitumor immunity. Upon validation, our human population data can likely inform translational research on the development of immunotherapy strategies targeting immune checkpoint mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (P01 CA87969 to M.J. Stampfer; UM1 CA186107 to M.J. Stampfer; P01 CA55075 to W.C. Willett; UM1 CA167552 to W.C. Willett; P50 CA127003 to C.S.F.; R01 CA137178 to A.T.C.; K24 DK098311 to A.T.C.; R01 CA151993 to S.O.; R35 CA197735 to S.O.; and K07 CA190673 to R.N.); Nodal Award from the Dana-Farber Harvard Cancer Center (to S.O.); and by grants from the Project P Fund, the Friends of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Bennett Family Fund, and the Entertainment Industry Foundation through National Colorectal Cancer Research Alliance. T.H. was supported by a fellowship grant from the Uehara Memorial Foundation and by a grant from the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research. K.K. was supported by a grant from Program for Advancing Strategic International Networks to Accelerate the Circulation of Talented Researchers from Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science. L.L. was supported by a scholarship grant from Chinese Scholarship Council and a fellowship grant from Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CIMP

CpG island methylator phenotype

- FFPE

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- LINE-1

long interspersed nucleotide element-1

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- OR

odds ratio

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- TILs

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- TMA

tissue microarray

Footnotes

Use of standardized official symbols: We use Human Genome Organisation (HUGO)-approved official symbols (or root symbols) for genes and gene products, including BRAF, CACNA1G, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD274, CDKN2A, CRABP1, CSF2, FOXP3, IFNG, IGF2, IL4, KRAS, MLH1, NEUROG1, PDCD1, PDCD1LG2, PIK3CA, PTPRC, RUNX3, and SOCS1; all of which are described at www.genenames.org. Gene names are italicized and gene product names are non-italicized.

Authors’ Contributions: C.S.F., Z.R.Q., and S.O. developed the main concept and designed the study. Y.M., R.N., T.H., M.S., A.dS., K.K., M.Gu., Y.S., W.L., L.L., D.N., K.I., Y.C., X.L., K.N., A.T.C., M.Gi., C.S.F., Z.R.Q., J.A.N., and S.O. were responsible for collection of tumor tissue, and acquisition of epidemiologic, clinical, and tumor tissue data, including histopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics. Y.M., R.N., M.S., D.N., C.S.F., Z.R.Q., and S.O. performed data analysis and interpretation. Y.M., T.H., M.S., and S.O. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to review and revision of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: A.T.C. previously served as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer Inc., and Aralez Pharmaceuticals. F.S.H. served as a consultant to Merck, Novartis, and Genentech and has received grant support to institution from Bristol-Myers Squibb. S.J.R. currently serves as a consultant for PerkinElmer. C.S.F. currently serves as a consultant for Genentech/Roche, Lilly, Sanofi, Bayer, Celgene, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Entrinsic Health, Five Prime Therapeutics, and Agios. This study was not funded by any of these companies. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Baumeister SH, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G, Sharpe AH. Coinhibitory Pathways in Immunotherapy for Cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2016;34:539–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:275–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smyth MJ, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Teng MW. Combination cancer immunotherapies tailored to the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:143–58. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7–H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:328rv4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teng MW, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Smyth MJ. Classifying Cancers Based on T-cell Infiltration and PD-L1. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2139–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasry A, Zinger A, Ben-Neriah Y. Inflammatory networks underlying colorectal cancer. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:230–40. doi: 10.1038/ni.3384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuipers EJ, Grady WM, Lieberman D, Seufferlein T, Sung JJ, Boelens PG, et al. Colorectal cancer. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2015:15065. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogino S, Galon J, Fuchs CS, Dranoff G. Cancer immunology--analysis of host and tumor factors for personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:711–9. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dienstmann R, Vermeulen L, Guinney J, Kopetz S, Tejpar S, Tabernero J. Consensus molecular subtypes and the evolution of precision medicine in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:79–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling A, Lundberg IV, Eklof V, Wikberg ML, Oberg A, Edin S, et al. The infiltration, and prognostic importance, of Th1 lymphocytes vary in molecular subgroups of colorectal cancer. J Pathol Clin Res. 2016;2:21–31. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mei Z, Liu Y, Liu C, Cui A, Liang Z, Wang G, et al. Tumour-infiltrating inflammation and prognosis in colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1595–605. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nosho K, Baba Y, Tanaka N, Shima K, Hayashi M, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Tumour-infiltrating T-cell subsets, molecular changes in colorectal cancer, and prognosis: cohort study and literature review. J Pathol. 2010;222:350–66. doi: 10.1002/path.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rozek LS, Schmit SL, Greenson JK, Tomsho LP, Rennert HS, Rennert G, et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes, Crohn’s-Like Lymphoid Reaction, and Survival From Colorectal Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016:108. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogino S, Nosho K, Irahara N, Meyerhardt JA, Baba Y, Shima K, et al. Lymphocytic reaction to colorectal cancer is associated with longer survival, independent of lymph node count, microsatellite instability, and CpG island methylator phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6412–20. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giannakis M, Mu XJ, Shukla SA, Qian ZR, Cohen O, Nishihara R, et al. Genomic Correlates of Immune-Cell Infiltrates in Colorectal Carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1206. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Llosa NJ, Cruise M, Tam A, Wicks EC, Hechenbleikner EM, Taube JM, et al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:43–51. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozali EN, Hato SV, Robinson BW, Lake RA, Lesterhuis WJ. Programmed death ligand 2 in cancer-induced immune suppression. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:656340. doi: 10.1155/2012/656340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latchman Y, Wood CR, Chernova T, Chaudhary D, Borde M, Chernova I, et al. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:261–8. doi: 10.1038/85330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danilova L, Wang H, Sunshine J, Kaunitz GJ, Cottrell TR, Xu H, et al. Association of PD-1/PD-L axis expression with cytolytic activity, mutational load, and prognosis in melanoma and other solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E7769–e77. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607836113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1596–606. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao Y, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Song M, Mima K, Inamura K, et al. Regular Aspirin Use Associates With Lower Risk of Colorectal Cancers With Low Numbers of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:879–92. e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in relation to the expression of COX-2. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2131–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, Halwani A, Scott EC, Gutierrez M, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi M, Roemer MG, Chapuy B, Liao X, Sun H, Pinkus GS, et al. Expression of programmed cell death 1 ligand 2 (PD-L2) is a distinguishing feature of primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma and associated with PDCD1LG2 copy gain. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1715–23. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derks S, Nason KS, Liao X, Stachler MD, Liu KX, Liu JB, et al. Epithelial PD-L2 Expression Marks Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1123–9. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sridharan V, Gjini E, Liao X, Chau NG, Haddad RI, Severgnini M, et al. Immune Profiling of Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma: PD-L2 Expression and Associations with Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:679–87. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masugi Y, Nishihara R, Yang J, Mima K, da Silva A, Shi Y, et al. Tumour CD274 (PD-L1) expression and T cells in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2017;66:1463–73. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamada T, Cao Y, Qian ZR, Masugi Y, Nowak JA, Yang J, et al. Aspirin Use and Colorectal Cancer Survival According to Tumor CD274 (Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1) Expression Status. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1836–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dou R, Nishihara R, Cao Y, Hamada T, Mima K, Masuda A, et al. MicroRNA let-7, T Cells, and Patient Survival in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:927–35. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mima K, Sukawa Y, Nishihara R, Qian ZR, Yamauchi M, Inamura K, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and T Cells in Colorectal Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:653–61. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kudryavtseva AV, Lipatova AV, Zaretsky AR, Moskalev AA, Fedorova MS, Rasskazova AS, et al. Important molecular genetic markers of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:53959–83. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Punt CJ, Koopman M, Vermeulen L. From tumour heterogeneity to advances in precision treatment of colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:235–46. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becht E, de Reynies A, Giraldo NA, Pilati C, Buttard B, Lacroix L, et al. Immune and Stromal Classification of Colorectal Cancer Is Associated with Molecular Subtypes and Relevant for Precision Immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:4057–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galon J, Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Angell HK, Berger A, Lagorce C, et al. Towards the introduction of the ‘Immunoscore’ in the classification of malignant tumours. J Pathol. 2014;232:199–209. doi: 10.1002/path.4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Angell HK, Maby P, Angelova M, Tougeron D, et al. Integrative Analyses of Colorectal Cancer Show Immunoscore Is a Stronger Predictor of Patient Survival Than Microsatellite Instability. Immunity. 2016;44:698–711. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham DM, Appelman HD. Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction and colorectal carcinoma: a potential histologic prognosticator. Mod Pathol. 1990;3:332–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vayrynen JP, Sajanti SA, Klintrup K, Makela J, Herzig KH, Karttunen TJ, et al. Characteristics and significance of colorectal cancer associated lymphoid reaction. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2126–35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Caro G, Bergomas F, Grizzi F, Doni A, Bianchi P, Malesci A, et al. Occurrence of tertiary lymphoid tissue is associated with T-cell infiltration and predicts better prognosis in early-stage colorectal cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2147–58. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vinuesa CG, Linterman MA, Yu D, MacLennan IC. Follicular Helper T Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2016;34:335–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taube JM, Klein A, Brahmer JR, Xu H, Pan X, Kim JH, et al. Association of PD-1, PD-1 ligands, and other features of the tumor immune microenvironment with response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5064–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yearley JH, Gibson C, Yu N, Moon C, Murphy E, Juco J, et al. PD-L2 Expression in Human Tumors: Relevance to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3158–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang H, Bueso-Ramos C, DiNardo C, Estecio MR, Davanlou M, Geng QR, et al. Expression of PD-L1, PD-L2, PD-1 and CTLA4 in myelodysplastic syndromes is enhanced by treatment with hypomethylating agents. Leukemia. 2014;28:1280–8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dinesh RK, Hahn BH, Singh RP. PD-1, gender, and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:583–7. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen Z, Rodriguez-Garcia M, Patel MV, Barr FD, Wira CR. Menopausal status influences the expression of programmed death (PD)-1 and its ligand PD-L1 on immune cells from the human female reproductive tract. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;76:118–25. doi: 10.1111/aji.12532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baptista MZ, Sarian LO, Derchain SF, Pinto GA, Vassallo J. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 and PD-L2 in breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2016;47:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogino S, Nishihara R, VanderWeele TJ, Wang M, Nishi A, Lochhead P, et al. Review Article: The Role of Molecular Pathological Epidemiology in the Study of Neoplastic and Non-neoplastic Diseases in the Era of Precision Medicine. Epidemiology. 2016;27:602–11. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rescigno T, Micolucci L, Tecce MF, Capasso A. Bioactive Nutrients and Nutrigenomics in Age-Related Diseases. Molecules. 2017:22. doi: 10.3390/molecules22010105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serafino A, Sferrazza G, Colini Baldeschi A, Nicotera G, Andreola F, Pittaluga E, et al. Developing drugs that target the Wnt pathway: recent approaches in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2017;12:169–86. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2017.1271321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.