Abstract

Despite decades of research, the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder (BD) is still not well understood. Structural brain differences have been associated with BD, but results from neuroimaging studies have been inconsistent. To address this, we performed the largest study to date of cortical gray matter thickness and surface area measures from brain magnetic resonance imaging scans of 6503 individuals including 1837 unrelated adults with BD and 2582 unrelated healthy controls for group differences while also examining the effects of commonly prescribed medications, age of illness onset, history of psychosis, mood state, age and sex differences on cortical regions. In BD, cortical gray matter was thinner in frontal, temporal and parietal regions of both brain hemispheres. BD had the strongest effects on left pars opercularis (Cohen’s d=−0.293; P=1.71 × 10−21), left fusiform gyrus (d=−0.288; P=8.25 × 10−21) and left rostral middle frontal cortex (d=−0.276; P=2.99 × 10−19). Longer duration of illness (after accounting for age at the time of scanning) was associated with reduced cortical thickness in frontal, medial parietal and occipital regions. We found that several commonly prescribed medications, including lithium, antiepileptic and antipsychotic treatment showed significant associations with cortical thickness and surface area, even after accounting for patients who received multiple medications. We found evidence of reduced cortical surface area associated with a history of psychosis but no associations with mood state at the time of scanning. Our analysis revealed previously undetected associations and provides an extensive analysis of potential confounding variables in neuroimaging studies of BD.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is among the most debilitating psychiatric disorders and affects 1–3% of the adult population worldwide.1, 2 BD is known to be highly heritable with individual risk depending partially on genetics.3, 4 However, the underlying neurobiological mechanism of the disorder remains unclear. The prognosis for individuals with BD is mixed: currently approved medications are ineffective for many patients.5, 6, 7, 8 Treatment regimens for patients with BD include several different medication types, including lithium, antiepileptics, antipsychotics and antidepressants.2 Some of the most commonly prescribed medications for patients with BD—including lithium9, 10, 11, 12 and antiepileptics13—have also been associated with structural brain differences, but the scope of these effects have not been systematically investigated. Many individuals with BD are initially misdiagnosed14 and may receive inappropriate treatments15, 16, 17 before presenting symptoms distinguishable from those of related disorders, such as major depressive disorder.

Examinations of consistently detected, BD-specific structural brain abnormalities will increase our neurobiological understanding of the illness. Relative to matched controls, BD patients show alterations in cortical thickness, surface area and the overall gray matter volume18, 19 measures that relate to functional impairments in cognition, behavior and symptom domains.20, 21 Cortical thickness and surface area are highly heritable22, 23 and may be affected by largely distinct sets of genes.24, 25 By examining regional cortical thickness and surface area differences in individuals with BD relative to healthy controls, we may identify biologically meaningful markers of disease.

Brain abnormalities associated with BD are challenging to identify, as BD is notoriously heterogeneous in symptom profile and cycles.14 A retrospective literature-based meta-analysis of cortical thickness26 found that the most consistent differences between individuals with BD and healthy controls were reduced thickness in the left anterior cingulate,27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 left paracingulate,27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33 left superior temporal gyrus27, 28, 32, 33, 34, 35 and prefrontal regions bilaterally.27, 28, 29, 32, 33, 34, 36, 37 Reports of surface area abnormalities associated with BD are mixed, and the largest study to date (N=346) failed to detect surface area differences between BD cases versus controls.33 Overall, there remains considerable uncertainty about the direction and anatomical profile of effects: many studies report no effect in specific cortical regions or significant effects in brain regions inconsistent with prior studies. Therefore, our understanding of BD cortical changes could be improved through a large-scale coordinated and harmonized analysis of the vast amounts of existing data to map brain differences in heterogeneous patient populations worldwide.

We formed the Bipolar Disorder Working Group within the ENIGMA Consortium38, 39 with the overarching goal of identifying consistent brain alterations associated with BD and elucidating and controlling for moderating factors that may affect the pathophysiology of BD. This new effort builds upon our previous effort looking at subcortical differences associated with BD40 and examines structural brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and clinical data from 6503 individuals (2447 of which were BD patients) with the aim of identifying differences in cortical regions consistently associated with BD with unprecedented power. In this large sample, we sought to examine effects of: (1) diagnosis, (2) age and sex, (3) subtype diagnosis, (4) duration of illness, (5) medication differences, (6) history of psychosis, and (7) mood state in adults and adolescents/young adults.

Materials and Methods

Samples

The ENIGMA BD Working Group includes 28 international groups with brain MRI scans and clinical data from BD patients and healthy controls. Overall, we analyzed data from 6503 people, including 2447 BD patients and 4056 healthy controls (including 1837 unrelated adult patients with BD compared with 2582 unrelated adult healthy controls). Each cohort’s demographics are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Supplementary Table S2 gives the instrument used to obtain diagnosis and medication information and Supplementary Table S3 lists exclusion criteria for study enrolment. All participating sites obtained approval from their local institutional review boards and ethics committees, and all study participants provided written informed consent.

Image processing and analysis

Structural T1-weighted MRI brain scans were acquired at each site and analyzed locally using harmonized analysis and quality-control protocols from the ENIGMA consortium that have previously been applied in large-scale studies of major depression.41 Image acquisition parameters and software descriptions are given in Supplementary Table S4. Cortical segmentations and parcellations for each cohort were created with the freely available and validated segmentation software, FreeSurfer.42 Segmentations of 68 (34 left and 34 right) cortical gray matter regions were created based on the Desikan–Killiany atlas43 (as well as the hemispheric total surface area and average cortical thickness). Segmented regions were visually inspected and statistically evaluated for outliers following standardized ENIGMA protocols (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/protocols/imaging-protocols). Individual sites were provided with examples of good/poor segmentation across the cortex. Diagnostic histogram plots were generated for each site and outlier subjects were flagged for further review (shared with DPH).

Statistical models of cortical differences

We examined group differences in cortical thickness and pial surface area between patients and controls using mixed-effect models, accounting for site as a random effect. Our focus was to examine differences in adults (defined as ⩾25 years at the time of scanning) and separately cortical differences in adolescents/young adults (defined as <25 years at the time of scanning). In the analysis of adults, the outcome measures were from each of the 70 cortical region of interests (ROIs; 68 regions and two whole-hemisphere average thickness or total surface area measures). A binary indicator of diagnosis (0=controls, 1=patients) was the predictor of interest. All cortical thickness models were adjusted for age and sex; all cortical surface area models were corrected for intracranial volume, age, sex, age-by-sex, age-squared and age-squared-by-sex to account for any higher-order effects on cortical surface area of age and sex as well as head size, which do not appear to be detectable for cortical thickness measures.44 Effect size estimates were calculated using the Cohen’s d metric computed from the t-statistic of the diagnosis indicator variable from the regression models. Similarly, for models testing interactions the predictor of interest was the product of two variables (that is, sex-by-diagnosis and age-by-diagnosis), with the main effect of each predictor included in the model. The effect size was calculated using the same procedure. In cases where the predictor of interest was a continuous variable (for example, duration of illness), we calculated the Pearson’s r effect size from the t-statistic of the predictor in the regression model. Throughout the manuscript, we report uncorrected P-values, with a significance threshold over all tests in the study determined by the false discovery rate procedure at q=0.05.45

We further examined patient-specific clinical characteristics, including diagnosis subtype, medication, duration of illness, history of psychosis and mood state at the time of scanning for effects on cortical thickness and surface area. Patients with a subtype diagnosis of BD type 1 or type 2 were compared with each other using the same statistical framework detailed above. Information on the instrument used for subtype diagnosis is available in Supplementary Table S2. Medications at the time of scanning (not including past medication exposure) were grouped into five major categories (lithium, antidepressants, antiepileptics, atypical and typical antipsychotics) and were jointly examined for effects on cortical thickness and surface area, within the same model. More specifically, we created a series of binary indicator variables for each medication type where a given subject was either 1—taking the medication—or 0—not taking the medication. All medication variables were included as predictors in a model (in addition to the confounding variables listed previously) with a cortical thickness or surface area measure as the outcome of interest. From this model, we were able to examine each medication predictor for its effect on a given cortical trait after accounting for all other medications. We also examined the effect of duration of illness, defined as the difference between age at the time of scan and age at first diagnosis. To minimize the likelihood of spurious correlations due to the high correlation between duration of illness and age at scan, while still being able to examine brain differences associated with illness duration, we performed a hierarchical regression with two levels. First, we used a multiple linear regression model with all potential confounding variables included and a given cortical thickness or surface area trait as the outcome. Next, we used a mixed-effect model with the residuals of the first model included as the outcome of interest, duration of illness as the predictor of interest and site as a random effect. We calculated effect-size estimates for each cortical trait from the t-statistics in this second model. We examined patient-specific differences in the cortex of BD patients with a lifetime history of psychosis. Patients with a history of psychosis were coded as 1 and those without were coded as 0. Mood state at the time of scanning, either euthymic or depressed (other mood states such as manic, hypomanic and mixed had insufficient numbers to perform a comparison), was examined for differential effects on the cortices of BD patients. In the comparison, euthymic patients were coded as 0 and depressed patients were coded as 1. Effect-size statistics were calculated as stated previously. Finally, we examined potential sources of bias based on imaging acquisition and analysis parameters, including field strength, voxel volume and FreeSurfer version. Field strength and FreeSurfer version were assessed for significance using a partial F-test where the full model included a factor with the imaging parameters in addition to the full set of covariates described above and the reduced model contained only the full set of covariates. Voxel volume was assessed directly for effect on cortical thickness and surface area and effect sizes were estimated based on the Pearson’s r of the voxel volume predictor in a model including the full set of covariates mentioned above.

Results

Widespread cortical thinning associated with BD in adults

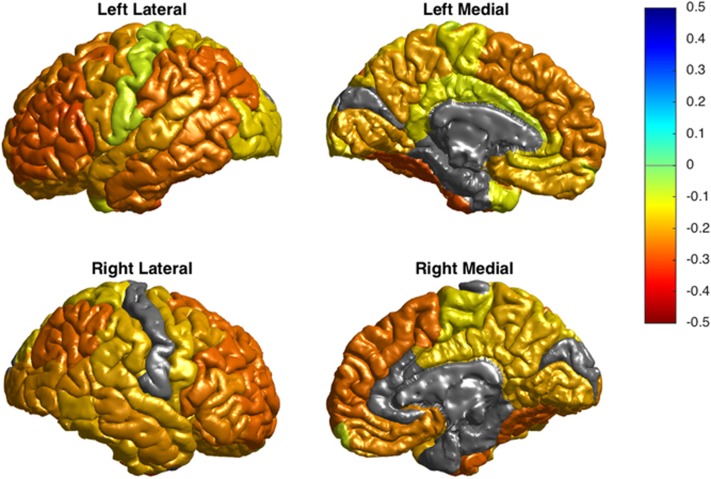

We found a significant and widespread pattern of reduced cortical thickness associated with BD (1837 BD patients, 2582 controls; Figure 1) with the largest effects in the left pars opercularis (Cohen’s d=−0.293; P=1.71 × 10−21), left fusiform gyrus (d=−0.288; P=8.25 × 10−21) and left rostral middle frontal cortex (d=−0.276; P=2.99 × 10−19). Large effects on average thickness over the left and right hemispheres were also present (d=−0.325; P=2.86 × 10−25; d=−0.303; P=3.35 × 10−22, respectively). Full results for the analysis of cortical thickness are presented in Table 1. We did not detect significant differences in cortical surface area ROIs associated with BD in adults (Supplementary Table S5). Further, we did not detect significant differences in cortical thickness or surface area ROIs (Supplementary Tables S7 and S8) for the sex-by-diagnosis interaction. We found evidence of an age-by-diagnosis interaction showing reduced surface area of the left posterior cingulate cortex (d=−0.100; P=0.00112) with increasing age. No other significant differences in cortical thickness or surface area for the age-by-diagnosis interaction were detected (Supplementary Tables S9 and S10).

Figure 1.

Cortical thinning in adult patients with bipolar disorder compared with healthy controls. Cohen’s d effect sizes are plotted for each region of interest on the cortical surface of a template image. Only significant regions are shown; non-significant regions are colored in gray.

Table 1. Cortical thickness differences associated with bipolar disorder in adults (age ⩾25 years).

| Cohen's d (BD versus CTL) | S.e. | 95% CI | % Difference | P-value | FDR P-value | # Controls | # Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left hemisphere average thickness | −0.325 | 0.031 | (−0.386 to −0.264) | −1.800 | 2.86 × 10−25 | 1.08 × 10−21 | 2559 | 1769 |

| Right hemisphere average thickness | −0.303 | 0.031 | (−0.364 to −0.242) | −1.707 | 3.35 × 10−22 | 6.33 × 10−19 | 2554 | 1768 |

| Left pars opercularis of inferior frontal gyrus | −0.293 | 0.031 | (−0.354 to −0.233) | −2.251 | 1.71 × 10−21 | 2.16 × 10−18 | 2581 | 1837 |

| Left fusiform gyrus | −0.288 | 0.031 | (−0.349 to −0.228) | −2.579 | 8.25 × 10−21 | 7.80 × 10−18 | 2580 | 1835 |

| Left rostral middle frontal gyrus | −0.276 | 0.031 | (−0.336 to −0.216) | −2.114 | 2.99 × 10−19 | 2.26 × 10−16 | 2579 | 1837 |

| Left pars triangularis of inferior frontal gyrus | −0.270 | 0.031 | (−0.33 to −0.21) | −2.258 | 1.65 × 10−18 | 1.04 × 10−15 | 2581 | 1837 |

| Right fusiform gyrus | −0.267 | 0.031 | (−0.327 to −0.207) | −2.431 | 4.77 × 10−18 | 2.58 × 10−15 | 2570 | 1833 |

| Left caudal middle frontal gyrus | −0.266 | 0.031 | (−0.326 to −0.206) | −2.074 | 5.85 × 10−18 | 2.76 × 10−15 | 2581 | 1835 |

| Left inferior parietal cortex | −0.265 | 0.031 | (−0.326 to −0.205) | −1.889 | 6.84 × 10−18 | 2.87 × 10−15 | 2580 | 1834 |

| Right rostral middle frontal gyrus | −0.264 | 0.031 | (−0.324 to −0.204) | −2.048 | 1.21 × 10−17 | 4.57 × 10−15 | 2572 | 1832 |

| Right inferior parietal cortex | −0.258 | 0.031 | (−0.318 to −0.198) | −1.911 | 5.19 × 10−17 | 1.78 × 10−14 | 2574 | 1834 |

| Right superior frontal gyrus | −0.256 | 0.031 | (−0.316 to −0.196) | −1.887 | 9.09 × 10−17 | 2.86 × 10−14 | 2574 | 1833 |

| Left supramarginal gyrus | −0.253 | 0.031 | (−0.313 to −0.192) | −1.852 | 2.30 × 10−16 | 6.70 × 10−14 | 2580 | 1837 |

| Left middle temporal gyrus | −0.252 | 0.031 | (−0.312 to −0.192) | −1.940 | 2.77 × 10−16 | 7.47 × 10−14 | 2579 | 1831 |

| Left inferior temporal gyrus | −0.250 | 0.031 | (−0.31 to −0.19) | −2.606 | 5.01 × 10−16 | 1.26 × 10−13 | 2576 | 1824 |

| Right pars opercularis of inferior frontal gyrus | −0.248 | 0.031 | (−0.308 to −0.188) | −1.925 | 7.95 × 10−16 | 1.88 × 10−13 | 2574 | 1834 |

| Left pars orbitalis of inferior frontal gyrus | −0.246 | 0.031 | (−0.306 to −0.186) | −2.236 | 1.34 × 10−15 | 2.98 × 10−13 | 2580 | 1837 |

| Right pars orbitalis of inferior frontal gyrus | −0.241 | 0.031 | (−0.301 to −0.181) | −2.154 | 4.85 × 10−15 | 1.02 × 10−12 | 2572 | 1835 |

| Left superior frontal gyrus | −0.233 | 0.031 | (−0.293 to −0.173) | −1.720 | 3.97 × 10−14 | 7.91 × 10−12 | 2581 | 1835 |

| Right pars triangularis of inferior frontal gyrus | −0.231 | 0.031 | (−0.291 to −0.171) | −1.913 | 6.79 × 10−14 | 1.28 × 10−11 | 2574 | 1835 |

| Right medial orbitofrontal cortex | −0.230 | 0.031 | (−0.29 to −0.17) | −2.177 | 9.15 × 10−14 | 1.65 × 10−11 | 2567 | 1823 |

| Right middle temporal gyrus | −0.219 | 0.031 | (−0.279 to −0.159) | −2.008 | 1.15 × 10−12 | 1.97 × 10−10 | 2572 | 1833 |

| Right lateral occipital cortex | −0.219 | 0.031 | (−0.279 to −0.159) | −1.613 | 1.24 × 10−12 | 2.03 × 10−10 | 2571 | 1832 |

| Left lateral orbitofrontal cortex | −0.216 | 0.031 | (−0.276 to −0.156) | −1.747 | 1.97 × 10−12 | 3.11 × 10−10 | 2581 | 1835 |

| Left precentral gyrus | −0.211 | 0.031 | (−0.271 to −0.151) | −1.695 | 7.37 × 10−12 | 1.12 × 10−9 | 2580 | 1833 |

| Left precuneus | −0.209 | 0.031 | (−0.269 to −0.149) | −1.528 | 1.04 × 10−11 | 1.51 × 10−9 | 2581 | 1837 |

| Left superior temporal gyrus | −0.209 | 0.031 | (−0.269 to −0.149) | −1.480 | 1.08 × 10−11 | 1.51 × 10−9 | 2574 | 1829 |

| Left lingual gyrus | −0.208 | 0.031 | (−0.268 to −0.148) | −1.563 | 1.26 × 10−11 | 1.71 × 10−9 | 2580 | 1835 |

| Right caudal middle frontal gyrus | −0.208 | 0.031 | (−0.268 to −0.148) | −1.639 | 1.32 × 10−11 | 1.72 × 10−9 | 2573 | 1835 |

| Left banks of superior temporal sulcus | −0.207 | 0.031 | (−0.267 to −0.147) | −1.682 | 1.61 × 10−11 | 2.03 × 10−9 | 2579 | 1830 |

| Right lateral orbitofrontal cortex | −0.207 | 0.031 | (−0.267 to −0.147) | −1.705 | 1.85 × 10−11 | 2.26 × 10−9 | 2573 | 1833 |

| Left medial orbitofrontal cortex | −0.199 | 0.031 | (−0.259 to −0.139) | −1.919 | 1.01 × 10−10 | 1.12 × 10−8 | 2572 | 1826 |

| Left insula | −0.198 | 0.031 | (−0.258 to −0.138) | −1.379 | 1.14 × 10−10 | 1.23 × 10−8 | 2578 | 1836 |

| Right lingual gyrus | −0.197 | 0.031 | (−0.257 to −0.137) | −1.470 | 1.40 × 10−10 | 1.47 × 10−8 | 2574 | 1835 |

| Right superior temporal gyrus | −0.194 | 0.031 | (−0.255 to −0.134) | −1.496 | 2.87 × 10−10 | 2.93 × 10−8 | 2564 | 1823 |

| Right inferior temporal gyrus | −0.189 | 0.031 | (−0.249 to −0.129) | −2.101 | 8.29 × 10−10 | 8.25 × 10−8 | 2572 | 1827 |

| Right precuneus | −0.188 | 0.031 | (−0.248 to −0.128) | −1.432 | 1.03 × 10−9 | 1.00 × 10−7 | 2574 | 1835 |

| Right supramarginal gyrus | −0.184 | 0.031 | (−0.245 to −0.124) | −1.379 | 2.12 × 10−9 | 2.00 × 10−7 | 2565 | 1828 |

| Right isthmus cingulate cortex | −0.183 | 0.031 | (−0.243 to −0.123) | −1.664 | 2.49 × 10−9 | 2.30 × 10−7 | 2573 | 1834 |

| Right precentral gyrus | −0.179 | 0.031 | (−0.239 to −0.119) | −1.450 | 6.14 × 10−9 | 5.40 × 10−7 | 2569 | 1830 |

| Right insula | −0.168 | 0.031 | (−0.228 to −0.108) | −1.166 | 4.64 × 10−8 | 3.58 × 10−6 | 2567 | 1832 |

| Right posterior cingulate cortex | −0.166 | 0.031 | (−0.226 to −0.106) | −1.282 | 6.20 × 10−8 | 4.60 × 10−6 | 2574 | 1834 |

| Left superior parietal cortex | −0.161 | 0.031 | (−0.221 to −0.102) | −1.259 | 1.46 × 10−7 | 1.01 × 10−5 | 2580 | 1837 |

| Right superior parietal cortex | −0.158 | 0.031 | (−0.218 to −0.098) | −1.357 | 2.53 × 10−7 | 1.70 × 10−5 | 2574 | 1834 |

| Left lateral occipital cortex | −0.156 | 0.031 | (−0.216 to −0.096) | −1.103 | 3.63 × 10−7 | 2.36 × 10−5 | 2577 | 1832 |

| Left rostral anterior cingulate cortex | −0.153 | 0.031 | (−0.213 to −0.093) | −1.523 | 5.97 × 10−7 | 3.82 × 10−5 | 2578 | 1834 |

| Right paracentral lobule | −0.140 | 0.031 | (−0.2 to −0.08) | −1.164 | 5.24 × 10−6 | 2.91 × 10−4 | 2574 | 1834 |

| Left paracentral lobule | −0.137 | 0.031 | (−0.197 to −0.077) | −1.170 | 7.71 × 10−6 | 4.10 × 10−4 | 2581 | 1836 |

| Left isthmus cingulate cortex | −0.132 | 0.031 | (−0.192 to −0.073) | −1.194 | 1.60 × 10−5 | 7.36 × 10−4 | 2580 | 1836 |

| Right banks of superior temporal sulcus | −0.125 | 0.031 | (−0.185 to −0.065) | −1.037 | 5.00 × 10−5 | 2.05 × 10−3 | 2574 | 1832 |

| Left transverse temporal gyrus | −0.120 | 0.031 | (−0.18 to −0.06) | −1.280 | 9.06 × 10−5 | 3.64 × 10−3 | 2579 | 1837 |

| Left frontal pole | −0.118 | 0.031 | (−0.178 to −0.058) | −1.401 | 1.18 × 10−4 | 4.71 × 10−3 | 2578 | 1836 |

| Left temporal pole | −0.116 | 0.031 | (−0.176 to −0.056) | −1.745 | 1.70 × 10−4 | 6.22 × 10−3 | 2572 | 1812 |

| Left posterior cingulate cortex | −0.112 | 0.031 | (−0.172 to −0.052) | −0.824 | 2.74 × 10−4 | 9.24 × 10−3 | 2580 | 1837 |

| Right transverse temporal gyrus | −0.109 | 0.031 | (−0.169 to −0.049) | −1.182 | 3.76 × 10−4 | 0.012 | 2574 | 1834 |

| Right frontal pole | −0.102 | 0.031 | (−0.162 to −0.042) | −1.212 | 9.41 × 10−4 | 0.024 | 2570 | 1832 |

| Left postcentral gyrus | −0.096 | 0.031 | (−0.156 to −0.036) | −0.782 | 1.79 × 10−3 | 0.040 | 2580 | 1830 |

| Left caudal anterior cingulate cortex | −0.095 | 0.031 | (−0.155 to −0.035) | −1.007 | 1.88 × 10−3 | 0.042 | 2580 | 1836 |

| Right rostral anterior cingulate cortex | −0.087 | 0.031 | (−0.147 to −0.027) | −0.858 | 4.84 × 10−3 | 0.086 | 2570 | 1833 |

| Right parahippocampal gyrus | −0.086 | 0.031 | (−0.146 to −0.026) | −1.018 | 5.36 × 10−3 | 0.091 | 2573 | 1824 |

| Right entorhinal cortex | −0.084 | 0.031 | (−0.144 to −0.024) | −1.246 | 6.59 × 10−3 | 0.105 | 2567 | 1797 |

| Right postcentral gyrus | −0.075 | 0.031 | (−0.135 to −0.015) | −0.638 | 0.014 | 0.178 | 2570 | 1828 |

| Right caudal anterior cingulate cortex | −0.063 | 0.031 | (−0.123 to −0.003) | −0.663 | 0.039 | 0.329 | 2571 | 1834 |

| Right temporal pole | −0.059 | 0.031 | (−0.119 to 0.001) | −0.912 | 0.057 | 0.391 | 2563 | 1810 |

| Left cuneus | −0.056 | 0.031 | (−0.116 to 0.004) | −0.526 | 0.068 | 0.421 | 2579 | 1835 |

| Left entorhinal cortex | −0.036 | 0.031 | (−0.096 to 0.024) | −0.492 | 0.244 | 0.691 | 2569 | 1803 |

| Right cuneus | −0.029 | 0.031 | (−0.089 to 0.031) | −0.266 | 0.352 | 0.774 | 2572 | 1833 |

| Left parahippocampal gyrus | −0.022 | 0.031 | (−0.082 to 0.038) | −0.271 | 0.479 | 0.839 | 2581 | 1820 |

| Left pericalcarine cortex | 0.020 | 0.031 | (−0.04 to 0.08) | 0.236 | 0.510 | 0.843 | 2578 | 1836 |

| Right pericalcarine cortex | 0.015 | 0.031 | (−0.045 to 0.075) | 0.173 | 0.626 | 0.896 | 2574 | 1832 |

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; CI, confidence interval; CTL, control; FDR, false discovery rate.

No significant cortical thickness or surface area differences between BD subtypes

We compared 1275 unrelated, adult patients diagnosed with BD type 1 with 345 unrelated, adult patients diagnosed with BD type 2. We did not detect significant differences in cortical thickness or surface area ROIs associated with subtype (Supplementary Tables S11 and S12).

Significant association of duration of illness on cortical thickness but not surface area

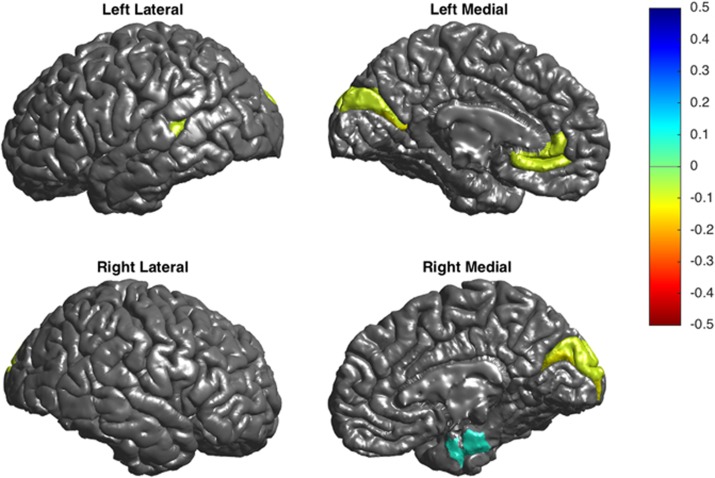

We found a broad pattern of reduced cortical thickness significantly associated with longer illness duration with the strongest effects in the left and right pericalcarine gyrus (Pearson’s r=−0.129; P=1.35 × 10−6; r=−0.123; P=3.96 × 10−6), left rostral anterior cingulate gyrus (r=−0.091; P=6.09 × 10−4) and right cuneus (r=−0.090; P=7.44 × 10−4) and evidence of significantly increased thickness in the right entorhinal gyrus (r=0.089; P=9.19 × 10−4; Figure 2; Supplementary Table S13). Cortical surface area ROIs in adult BD patients were not significantly associated with illness duration (Supplementary Table S14).

Figure 2.

Cortical thinning in adult patients with bipolar disorder associated with duration of illness. Pearson’s correlation r effect sizes are plotted for each region of interest on the cortical surface of a template image. Only significant regions are shown; non-significant regions are colored in gray.

Widespread effects on cortical thickness and surface area associated with commonly prescribed medications in adults diagnosed with BD

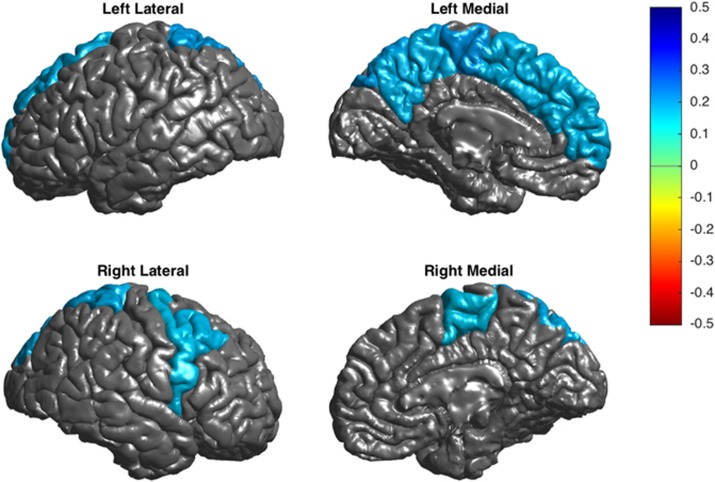

We examined cortical thickness and surface area differences associated with five major medication families: lithium, antiepileptics, antidepressants, and typical and atypical antipsychotics in adult patients with BD. We found significant evidence of increased cortical thickness associated with taking lithium (n=700; compared with those not taking lithium n=892), with the largest effects in the left paracentral gyrus (d=0.211; P=7.96 × 10−5) and the left and right superior parietal gyrus (d=0.202; P=1.60 × 10−4; d=0.188; P=4.39 × 10−4) (Figure 3; Supplementary Table S15). We also found evidence of increased surface area in the left paracentral lobule (d=0.17; P=0.0015; Supplementary Table S16).

Figure 3.

Cortical thickening in adult patients with bipolar disorder associated with lithium treatment. Cohen’s d effect sizes are plotted for each region of interest on the cortical surface of a template image. Only significant regions are shown; non-significant regions are colored in gray.

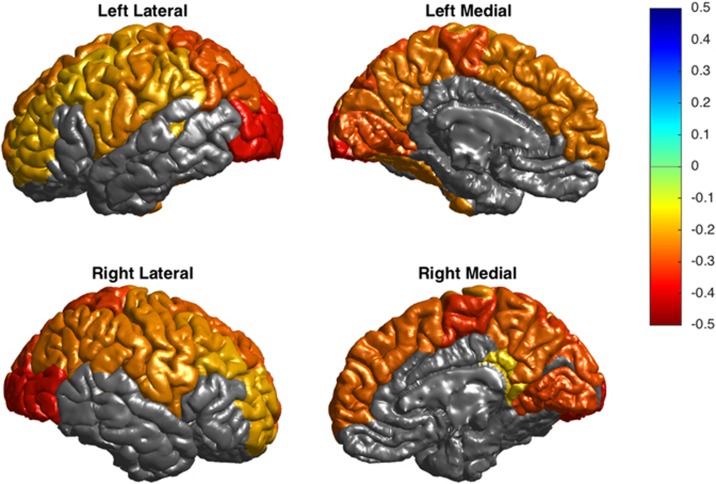

In the patient group, reduced cortical thickness was associated with antiepileptic treatment (n=576 compared with patients not taking antiepileptics n=932), with the largest effects in the left and right lateral occipital gyrus (d=−0.360; P=5.35 × 10−11; d=−0.357; P=7.24 × 10−11) and right paracentral gyrus (d=−0.326; P=2.57 × 10−9) (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S17). Cortical surface area was not significantly associated with antiepileptic treatment for any ROI (Supplementary Table S18).

Figure 4.

Cortical thinning in adult patients with bipolar disorder associated with antiepileptic treatment. Cohen’s d effect sizes are plotted for each region of interest on the cortical surface of a template image. Only significant regions are shown; non-significant regions are colored in gray.

Increased cortical surface area was associated with typical antipsychotic treatment (n=78 compared with patients not taking typical antipsychotics n=1419) in the left middle temporal gyrus (d=0.439; P=2.83 × 10−4), left inferior parietal gyrus (d=0.366; P=0.00213) and right temporal pole (d=0.382; P=0.00147; Supplementary Table S20). We did not detect any significant associations between cortical thickness and typical antipsychotic treatment (Supplementary Table S19).

We found significant evidence of reduced cortical surface area associated with atypical antipsychotic treatment (n=504 compared with patients not taking atypical antipsychotics n=994) in the right rostral middle frontal gyrus (d=−0.199; P=4.00 × 10−4) and right superior frontal gyrus (d=−0.187; P=8.61 × 10−4; Supplementary Table S22). We did not detect significant associations between cortical thickness and atypical antipsychotic treatment (see Supplementary Table S21).

We did not detect any significant association between in cortical thickness (Supplementary Table S23) or surface area (Supplementary Table S24) and antidepressant treatment.

Association of cortical surface area with history of psychosis and mood state findings at the time of scanning

When comparing 768 adult BD patients with a history of psychosis with 619 patients without a history of psychosis, we found evidence of reduced surface area in the right frontal pole of BD patients with a history of psychosis (d=−0.167; P=0.0023). We did not detect differences in cortical thickness or surface area in any other regions of interest (Supplementary Tables S25 and S26). Further, we did not detect differences in cortical thickness or surface area when comparing patients who were depressed at the time of scanning (n=210) with patients who were euthymic at the time of scanning (n=819) (Supplementary Tables S27 and S28). Comparisons with other mood states such as hypomanic, manic and mixed were not possible due to small sample sizes.

Association of cortical thickness and surface area with BD in adolescents/young adults/young adults

We compared cortical thickness and surface area between 411 adolescent/young adult patients diagnosed with BD and 1035 healthy adolescents/young adults/young adults (mean age: 21.1 years±3.1 s.d.; age of onset: 20.3±9.5 years; and age range: 8–24.9 years). We found significantly reduced thickness in the right supramarginal gyrus (d=−0.195; P=0.00102) and reduced surface area in the left insula (d=−0.184; P=0.00196) (Supplementary Tables S29 and S30) measures. We found a broad pattern of significant interactions between age and diagnosis whereby older BD patients had reduced cortical thickness beyond the effects of age and diagnosis, with the strongest effect observed in the left rostral middle frontal gyrus (d=−0.264; P=8.83 × 10−6). We further found evidence of an interaction between sex and diagnosis in the frontal and temporal lobe gyri whereby adolescent/young adult female BD patients showed less thinning than could be explained by sex and diagnosis with the strongest effect in the right pars triangularis (d=0.264; P=8.56 × 10−6). Fully tabulated results for the age-by-diagnosis and sex-by-diagnosis comparison with cortical thickness are available in Supplementary Tables S34 and S32, respectively. We did not detect significant differences in cortical surface area for the sex-by-diagnosis interaction (Supplementary Table S33) or the age-by-diagnosis interaction (Supplementary Table S35). When comparing 104 adolescent/young adult BD patients with a history of psychosis with 143 patients without a history of psychosis, we found evidence of reduced surface area in the left inferior temporal gyrus (d=−0.489; P=0.000513) and right caudal anterior cingulate cortex (d=−0.433; P=0.00204) of BD patients with a history of psychosis. We did not detect differences in cortical thickness (Supplementary Tables S50 and S51). Further, we did not detect differences in cortical thickness or surface area when comparing patients who were depressed at the time of scanning (n=53) with patients who were euthymic at the time of scanning (n=133) (Supplementary Tables S52 and S53). Comparisons with other mood states such as hypomanic, manic and mixed were not possible due to small sample sizes. Further examinations of diagnosis subtype, duration of illness and medication effects in our adolescent/young adult sample are detailed in Supplementary Note S1. We did not find evidence of bias in cortical thickness and surface area estimates by field strength, FreeSurfer version or voxel volume in adults or adolescents/young adults (Supplementary Note S2).

Discussion

Here we present a highly powered study on structural brain differences in the cortex of patients with BD using the largest sample to date. Relative to healthy controls, adults with BD had widespread bilateral patterns of reduced cortical thickness in frontal, temporal and parietal regions. In adolescents/young adults/young adults, we found reduced thickness and surface area in the supramarginal gyrus and insula (respectively) associated with BD.

In addition, we found evidence of significant age-by-diagnosis effects whereby older adolescent/young adult patients with BD had additional cortical thinning beyond what could be explained by the effects of age and diagnosis alone. This interaction may capture the accelerated thinning associated with age-related brain changes and the pathophysiology of BD. We also found evidence of significant sex-by-diagnosis effects whereby adolescent/young adult female BD patients have less thinning than would be expected based on sex and diagnosis effects alone. The dampened cortical thinning of adolescent/young adult female patients with BD may reflect the sexual dimorphism in cortical development in which females, in general, have a thicker cortex than males.46 However, this interaction effect was not detected in our comparisons of adults and therefore appears to not be present at later stages in life. However, these findings should be confirmed in independent samples and ideally in longitudinal studies.

Interestingly, even in the current highly powered sample, only one of the analyses of diagnosis showed evidence of effects on cortical surface area (reduced surface area in the insula of adolescents/young adults). When reanalyzing the surface area differences without head size as a covariate (that is, with the intracranial volume covariate removed), an additional region of interest (right entorhinal gyrus) showed a significantly increased surface area in adults with BD (Supplementary Tables S6 and S31). In general, BD appears to be associated with reduced cortical thickness but not surface area. Cortical thickness is thought to be a localized measure of neuron numbers within a cortical layer while surface area is a measure of cortical column layer numbers and overall size of the cortex.18, 19, 47 It is therefore possible that the neurobiological mechanisms associated with BD reduce neuron numbers but do not affect overall size of the cortex or cortical columnar organization.

We examined the effects of five major drug families (lithium, antiepileptics, antidepressants, atypical and typical antipsychotics) on cortical thickness and surface area in BD patients. Our statistical model accounted for different drug combinations across individuals. In adults and adolescents/young adults, treatment with lithium or antiepileptics showed significant evidence of effect on cortical thickness (whereas lithium was positively associated with cortical thickness, antipsychotics showed a negative relationship). Prior studies of these medication types found a similar pattern of effects on surface area and thickness throughout the brain.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 The increased cortical thickness associated with lithium treatment is hypothesized to be driven by a neurotrophic effect of lithium on gray matter.11, 48 Interestingly, the regions with the lowest thickness associated with antiepileptic treatment were the primary visual processing areas, in the occipital lobe. Treatment with antiepileptics has previously been reported to be associated with visual deficits.49 We found evidence of reduced cortical surface area with atypical antipsychotics, which is in line with previous prospective longitudinal studies in schizophrenia.50, 51 Our finding of increased cortical surface area associated with typical antipsychotics is difficult to interpret. The total number of patients in our sample taking typical antipsychotics was quite small (about 5%). Further efforts are needed with larger sample sizes to examine this effect more definitively. Our findings highlight the importance of accounting and controlling for medications when assessing brain differences in patients with BD.

We did not detect thickness or surface area differences between adult patients diagnosed with BD type 1 versus type 2. This is consistent with our prior work examining subcortical structural alterations in BD, where we also did not find significant volumetric differences between BD subtypes.40 Several previous studies have identified differences in cortical thickness and surface area associated with BD type 1 that do not appear to be apparent in type 2.13, 33 However, most large meta-analyses have failed to detect a difference between disorders subtypes.52, 53 Despite the differences in clinical presentation of patients with BD type 1 and type 2, analyses of brain structure and genetics indicate that there are few detectable differences between the subtypes.13, 33, 53, 54 It appears then that the current measures of cortical and subcortical structures are not sensitive to differences in subtype. It is possible that the subtype differences are more focal and remain undetected in this ROI-based analysis. Efforts that examine vertexwise data can help examine these issues with a greater resolution across the cortex. In addition, it should be noted that the number of adult patients diagnosed with BD type 2 (n=345) was lower than those with BD type 1 (n=1275). A larger (better balanced) sample size in both groups would help determine the differences more definitively.

We investigated the effect of mood state at the time of scanning as well as patient history of psychosis for effects on the cortex. In adult and adolescent/young adult patients with BD, we did not find evidence of significant differences in cortical thickness or surface area associated with a euthymic or depressed mood state at the time of scanning. The total sample size for other additional mood states (that is, manic, hypomanic, mixed) were too small to allow for comparisons across groups. This suggests that mood state at the time of scanning, at least for euthymic and depressed patients, does not influence cortical thickness and surface area measurements. However, different aspects of mood such as length of time in a given mood state or number of episodes are potential areas for further study though those measures were either unavailable or unreliable in the majority of site participating in this analysis. When we examined adult and adolescent/young adult BD patients with at least one previous episode of psychosis within or outside of an affective episode compared with patients without a history of psychosis, we found evidence of reduced cortical surface area associated with a history of psychosis in the frontal pole of adults and the inferior temporal gyrus and caudal anterior cingulate cortex in adolescents/young adults with a history of psychosis. However, the periodic nature of psychotic symptoms and the heterogeneity in collection across sites in this study limit our interpretation. In addition, the overall sizes of the effects on the cortex, while significant, are quite low. Future work should characterize psychotic symptoms in a prospectively designed and ideally large, cohort study.

Duration of illness has previously been suggested to have effects on cortical thickness in BD.55, 56 Our study is cross-sectional, that is, we are not observing changes in thickness over time but instead evaluating patients with varying durations of illness. We did find significant evidence of reduced cortical thickness associated with longer duration of illness in adults with BD in the occipital cortex, left parietal and right frontal cortex. However, our current cross-sectional model limits the interpretation of effects that depend on the duration of illness. Large-scale, longitudinal studies of BD are needed to specifically examine how illness duration and treatment over time affects the brain. Several such efforts are underway,57, 58, 59 but greater resources are needed in this area to increase power to identify robust effects.

Strengths of this study include a large sample size and harmonized analysis of the cortex, but there are several limitations: (1) samples come from heterogeneous sources—from centers around the world. Although we explicitly model differences between sites (including imaging parameters, such as field strength, FreeSurfer version and voxel volume), sources of heterogeneity (such as treatment response, stage of illness, ethnicity/race) in our estimates still remain. BD itself is quite heterogeneous, and while we attempt to model sources of heterogeneity both in the clinic and at the level of the patient, the overall effect sizes observed in this study are quite small. This suggests that the value of cortical thickness and surface area as a biomarker will likely be strongest when examined in combination with risk gene variants and additional biomarkers that reflect variation in other aspects of the disorder; (2) we examined the moderating effects of commonly prescribed medications, but our cross-sectional data represent only a snapshot of the medication history of a given subject. Although we believe that our medication models do reveal distinct and biologically meaningful patterns of effects on the cortex, we acknowledge that a large, prospective and longitudinal study of BD is the best way to disentangle these effects; (3) several moderating factors (for example, alcohol dependence,60 smoking,61, 62 substance abuse63) may influence cortical structure but were not included in this study as these data were not available in a large portion of the data sets; (4) we examined subjects with a diagnosis of BD excluding patients with head trauma or neurological disorders; however, many sites enrolled patients with co-morbid psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and personality disorders. It therefore remains possible that the effects described here are affected by comorbid diagnoses; and (5) these data are focused on the structure of the cortex including thickness and surface area. Patterns of effects (and lack of effects) may differ when examining other brain imaging modalities (for example, white matter tracts64 and resting state networks65). Integrating multimodal information on BD will likely improve our understanding of the disorder and help the development of biomarkers. However, large-scale, mono-modality analyses are necessary to first determine the effectiveness of a given modality and its suitability for inclusion in future multi-modal study designs.

In general, our findings are consistent with prior reports of a thinner frontal and temporal cortex in BD.26 The brain regions associated with the largest reductions in cortical thickness in adult patients diagnosed with BD were located in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), which has been an area of considerable focus and study in the BD literature.66 Functional brain imaging studies have shown increased activity in the VLPFC in remitted BD during emotion regulation67 and increased activity in depressed BD during a cognitive task (planning) compared with depressed major depressive disorder.68 Functional and structural abnormalities in the VLPFC of unaffected first-degree relatives have also been observed.69, 70 The findings in this study not only confirm the most consistent effects from prior studies but also provide novel evidence of effects showing that: (1) inferior parietal regions are associated with significantly reduced thickness in adults with BD; and (2) inferior temporal regions (including the fusiform gyrus and middle temporal gyrus) are associated with reduced cortical thickness in adults with BD. The inferior parietal lobe is involved in sensorimotor integration of the mirror neuron system71 and language tasks.72 Structural deficits in these brain regions may be implicated in changes in emotion perception associated with BD, which in turn are suggested to explain fluctuating or rapid changes in mood.73, 74 The inferior temporal lobe—comprised of the middle and inferior temporal gyrus and the fusiform gyrus—has a major role in the ventral stream of visual processing and spatial awareness. Further, the inferior temporal lobe receives dense neuronal projections from the amygdala and is hypothesized to feed visual perceptions into the emotion processing circuit.75 Our analysis of a family-based cohort enriched for BD (UCLA-BP; n=527) shows a similar pattern of effects in the frontal and temporal lobes. However, regional differences in the occipital lobe were not associated with BD in the UCLA-BP cohort. We previously showed that limbic subcortical structures (including the hippocampus and thalamus), which receive dense connections with frontal and temporal lobe regions, showed evidence of volumetric reductions in BD.40 A prior analysis of heritability in the UCLA-BP cohort shows that frontal and temporal lobe differences are both partially heritable and attributable to BD pathophysiology.76 It should be noted that decreased cortical thickness in general is not specific to BD; it has been shown in other related disorders such as schizophrenia33 and major depression.41 Future efforts should examine the value of cortical thickness and surface area as a pattern of effects across the cortex for distinguishing major psychiatric disorders. While we demonstrate a clear pattern of cortical thinning associated with BD, future endeavors should examine the value of these measures for improving the lives of patients including in studies of quality of life, patient outcomes and early detection and intervention.

Acknowledgments

The ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder working group gratefully acknowledges support from the NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) award (U54 EB020403 to PMT). We thank the members of the International Group for the Study of Lithium Treated Patients (IGSLi) and Costa Rica/Colombia Consortium for Genetic Investigation of Bipolar Endophenotypes. We also thank research funding sources: The Halifax studies have been supported by grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (103703, 106469, 64410 and 142255), the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, Dalhousie Clinical Research Scholarship to TH. TOP is supported by the Research Council of Norway (223273, 213837, 249711), the South East Norway Health Authority (2017-112), the Kristian Gerhard Jebsen Stiftelsen (SKGJ‐MED‐008) and the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013), grant agreement no. 602450 (IMAGEMEND). Cardiff is supported by the National Centre for Mental Health (NCMH), Bipolar Disorder Research Network (BDRN) and the 2010 NARSAD Young Investigator Award (ref. 17319) to XC. The Paris sample is supported by the French National Agency for Research (ANR MNP 2008 to the ‘VIP’ project) and by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (2014 Bio-informarcis grant). The St. Göran bipolar project (SBP) is supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council, the Swedish foundation for Strategic Research, the Swedish Brain foundation and the Swedish Federal Government under the LUA/ALF agreement. The Malt-Oslo sample is supported by the South East Norway Health Authority and by generous unrestricted grants from Mrs. Throne-Holst. The UT Houston sample is supported by NIH grant, MH085667. The UCLA-BP study is supported by NIH grants R01MH075007, R01MH095454, P30NS062691 (to NBF), K23MH074644-01 (to CEB) and K08MH086786 (to SF). Data collection for the UMCU sample is funded by the NIMH R01 MH090553 (PI Ophoff). The Oxford/Newcastle sample was funded by the Brain Behavior Research Foundation and Stanley Medical Research Institute. The University of Barcelona sample is supported by the CIBERSAM, the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (PI 12/00910), and the Comissionat per a Universitats i Recerca del DIUE de la Generalitat de Catalunya (2014 SGR 398). The KCL group is supported by a MRC Fellowship MR/J008915/1 (PI Kempton). The NUIG sample was supported by the Health Research Board (HRA_POR/2011/100). The Sydney sample was funded by the Australian National Medical and Health Research Council (Program Grant 1037196; project grant 1066177) and the Lansdowne Foundation and supported by philanthropic donations from Janette O’Neil and Paul and Jenny Reid. SF was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under grant R01MH104284. DD is partially supported by a NARSAD 2014 Young Investigator Award (Leichtung Family Investigator) and a Psychiatric Research Trust grant (2014). The Münster Sample was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), grant FOR2107, DA1151/5-1 to UD. The Penn sample was funded by NIH grants K23MH098130 (to TDS), K23MH085096 (to DHW), R01MH107703 (to TDS) and R01MH101111 (to DHW), as well as support from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. The Tulsa studies were supported by the William K. Warren Foundation. Partial support was also received from the NIMH (K01MH096077). The Pittsburgh sample was funded by 5R01MH076971 (PI Phillips) and the Pittsburgh Foundation (Phillips). The Sao Paulo (Brazil) studies have been supported by grants from FAPESP-Brazil (#2009/14891-9, 2010/18672-7, 2012/23796-2 and 2013/03905-4), CNPq-Brazil (#478466/2009 and 480370/2009), the Wellcome Trust (UK) and the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (2010 NARSAD Independent Investigator Award granted to GFB). MB and AP received support from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the framework of the BipolLife research network on bipolar disorders. Data from the AMC was supported by the Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), program Mental Health, education of investigators in mental health (OOG; #100-002-034). MMR used the e-Bioinfra Gateway to analyze data from the AMC (see Shahand et al. (2012): A grid-enabled gateway for biomedical data analysis. Journal of Grid Computing 1–18). The CliNG study sample was partially supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) via the Clinical Research Group 241 ‘Genotype-phenotype relationships and neurobiology of the longitudinal course of psychosis’, TP2 (PI Gruber; http://www.kfo241.de; grant number GR 1950/5-1). The FIDMAG Germànes Hospitalàries Research Foundation sample is supported by the Comissionat per a Universitats i Recerca del DIUE de la Generalitat de Catalunya (2014-SGR-1573) and several grants funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Co-funded by European Regional Development Fund/European Social Fund) “Investing in your future”): Miguel Servet Research Contract (CPII16/00018 to E. P.-C.), Sara Borrell Contract grant (CD16/00264 to M.F.-V.) and Research Projects (PI14/01148 to E.P.-C. and PI15/00277 to E.C.-R.).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/mp)

AMM has received funding from Lilly, Janssen and Pfizer. It is unconnected with the current work. TvE has a contract with Otsuka Pharmaceutical Inc. The contract is not related to this work. UFM participated in the speaker’s bureau for Lundbeck Norway and was a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals. ACB has received salaries from P1vital Ltd, which is unrelated to this work. PGR trained personnel for Janssen Pharmaceuticals. It is unconnected with the current work. DPH and WCD are employed by Janssen Research and Development, LLC. MB has received grant/research support from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), American Foundation of Suicide Prevention. MB is/has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ferrer Internacional, Janssen, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merz, Neuraxpharm, Novartis, Otsuka, Servier, Takeda, and has received speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Pfizer, which is all unrelated to this work. OAA has received speaker’s honorarium from Lundbeck, Otsuka and Lilly. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest. All authors have contributed to and approved the contents of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 241–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande I, Berk M, Birmaher B, Vieta E. Bipolar disorder. Lancet 2016; 387: 1561–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, Sham P, Katz R, Cardno A. The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60: 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray NR, Gottesman II. Using summary data from the danish national registers to estimate heritabilities for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Front Genet 2012; 3: 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Rapport DJ, Kimmel SE, Shelton MD. Controlled trials in bipolar I depression: focus on switch rates and efficacy. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999; 9(Suppl 4): S109–S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunner DL. Clinical consequences of under-recognized bipolar spectrum disorder. Bipolar Disord 2003; 5: 456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN, Lenox MS, Baldessarini RJ. Effectiveness and safety of long-term antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62: 565–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombs JS, Ahn J, Tencer T, Shi L. The impact of unrecognized bipolar disorders among patients treated for depression with antidepressants in the fee-for-services California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program: a 6-year retrospective analysis. J Affect Disord 2007; 97: 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GJ, Cortese BM, Glitz DA, Zajac-Benitez C, Quiroz JA, Uhde TW et al. A longitudinal study of the effects of lithium treatment on prefrontal and subgenual prefrontal gray matter volume in treatment-responsive bipolar disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70: 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GJ, Bebchuk JM, Wilds IB, Chen G, Menji HK. Lithium-induced increase in human brain grey matter. Lancet 2000; 356: 1241–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyoo IK, Dager SR, Kim JE, Yoon SJ, Friedman SD, Dunner DL et al. Lithium-induced gray matter volume increase as a neural correlate of treatment response in bipolar disorder: a longitudinal brain imaging study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010; 35: 1743–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek T, Bauer M, Simhandl C, Rybakowski J, O'Donovan C, Pfennig A et al. Neuroprotective effect of lithium on hippocampal volumes in bipolar disorder independent of long-term treatment response. Psychol Med 2014; 44: 507–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe C, Ekman CJ, Sellgren C, Petrovic P, Ingvar M, Landen M. Cortical thickness, volume and surface area in patients with bipolar disorder types I and II. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015; 41: 150093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden CL. A different depression: clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord 2005; 84: 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, Pandurangi AK, Goodwin K. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord 1999; 52: 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RM. The National Depressive and Manic-depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord 1994; 31: 281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morselli PL, Elgie R, Europe G. GAMIAN-Europe/BEAM survey I—global analysis of a patient questionnaire circulated to 3450 members of 12 European advocacy groups operating in the field of mood disorders. Bipolar Disord 2003; 5: 265–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. The radial edifice of cortical architecture: from neuronal silhouettes to genetic engineering. Brain Res Rev 2007; 55: 204–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science 1988; 241: 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartberg CB, Sundet K, Rimol LM, Haukvik UK, Lange EH, Nesvag R et al. Brain cortical thickness and surface area correlates of neurocognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and healthy adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2011; 17: 1080–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan JL, Tandon N, Haller CS, Mathew IT, Eack SM, Clementz BA et al. Correlations between brain structure and symptom dimensions of psychosis in schizophrenia, schizoaffective, and psychotic bipolar I disorders. Schizophr Bull 2015; 41: 154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen WS, Prom-Wormley E, Panizzon MS, Eyler LT, Fischl B, Neale MC et al. Genetic and environmental influences on the size of specific brain regions in midlife: the VETSA MRI study. Neuroimage 2010; 49: 1213–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokland GA, de Zubicaray GI, McMahon KL, Wright MJ. Genetic and environmental influences on neuroimaging phenotypes: a meta-analytical perspective on twin imaging studies. Twin Res Hum Genet 2012; 15: 351–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizzon MS, Fennema-Notestine C, Eyler LT, Jernigan TL, Prom-Wormley E, Neale M et al. Distinct genetic influences on cortical surface area and cortical thickness. Cereb Cortex 2009; 19: 2728–2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler AM, Kochunov P, Blangero J, Almasy L, Zilles K, Fox PT et al. Cortical thickness or grey matter volume? The importance of selecting the phenotype for imaging genetics studies. Neuroimage 2010; 53: 1135–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanford LC, Nazarov A, Hall GB, Sassi RB. Cortical thickness in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord 2016; 18: 4–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvsashagen T, Westlye LT, Boen E, Hol PK, Andreassen OA, Boye B et al. Bipolar II disorder is associated with thinning of prefrontal and temporal cortices involved in affect regulation. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 855–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty CE, Foland-Ross LC, Narr KL, Sugar CA, McGough JJ, Thompson PM et al. ADHD comorbidity can matter when assessing cortical thickness abnormalities in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2012; 14: 843–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foland-Ross LC, Thompson PM, Sugar CA, Madsen SK, Shen JK, Penfold C et al. Investigation of cortical thickness abnormalities in lithium-free adults with bipolar I disorder using cortical pattern matching. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168: 530–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornito A, Malhi GS, Lagopoulos J, Ivanovski B, Wood SJ, Saling MM et al. Anatomical abnormalities of the anterior cingulate and paracingulate cortex in patients with bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Res 2008; 162: 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornito A, Yucel M, Wood SJ, Bechdolf A, Carter S, Adamson C et al. Anterior cingulate cortex abnormalities associated with a first psychotic episode in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 194: 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyoo IK, Sung YH, Dager SR, Friedman SD, Lee JY, Kim SJ et al. Regional cerebral cortical thinning in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimol LM, Hartberg CB, Nesvag R, Fennema-Notestine C, Hagler DJ, Pung CJ et al. Cortical thickness and subcortical volumes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 68: 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller JJ, Thaveenthiran P, Thomson RH, McQueen S, Fitzgerald PB. Volumetric, cortical thickness and white matter integrity alterations in bipolar disorder type I and II. J Affect Disord 2014; 169: 118–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnanather JT, Cebron S, Ceyhan E, Postell E, Pisano DV, Poynton CB et al. Morphometric differences in planum temporale in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder revealed by statistical analysis of labeled cortical depth maps. Front Psychiatry 2014; 5: 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen J, Aleman-Gomez Y, Schnack H, Balaban E, Pina-Camacho L, Alfaro-Almagro F et al. Cortical morphology of adolescents with bipolar disorder and with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2014; 158: 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan MJ, Chhetry BT, Oquendo MA, Sublette ME, Sullivan G, Mann JJ et al. Cortical thickness differences between bipolar depression and major depressive disorder. Bipolar Disord 2014; 16: 378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibar DP, Stein JL, Renteria ME, Arias-Vasquez A, Desrivieres S, Jahanshad N et al. Common genetic variants influence human subcortical brain structures. Nature 2015; 520: 224–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Stein JL, Medland SE, Hibar DP, Vasquez AA, Renteria ME et al. The ENIGMA Consortium: large-scale collaborative analyses of neuroimaging and genetic data. Brain Imaging Behav 2014; 8: 153–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibar DP, Westlye LT, van Erp TG, Rasmussen J, Leonardo CD, Faskowitz J et al. Subcortical volumetric abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2016; 21: 1710–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaal L, Hibar DP, Samann PG, Hall GB, Baune BT, Jahanshad N et al. Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry advance online publication, 3 May 2016; doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 2002; 33: 341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 2006; 31: 968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlye LT, Walhovd KB, Dale AM, Bjornerud A, Due-Tonnessen P, Engvig A et al. Differentiating maturational and aging-related changes of the cerebral cortex by use of thickness and signal intensity. Neuroimage 2010; 52: 172–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol 1995; 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Im K, Lee JM, Lee J, Shin YW, Kim IY, Kwon JS et al. Gender difference analysis of cortical thickness in healthy young adults with surface-based methods. Neuroimage 2006; 31: 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontious A, Kowalczyk T, Englund C, Hevner RF. Role of intermediate progenitor cells in cerebral cortex development. Dev Neurosci 2008; 30: 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Zeng WZ, Yuan PX, Huang LD, Jiang YM, Zhao ZH et al. The mood-stabilizing agents lithium and valproate robustly increase the levels of the neuroprotective protein bcl-2 in the CNS. J Neurochem 1999; 72: 879–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton EJ, Hosking SL, Betts T. The effect of antiepileptic drugs on visual performance. Seizure 2004; 13: 113–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Ziebell S, Pierson R, Magnotta V. Long-term antipsychotic treatment and brain volumes: a longitudinal study of first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Smieskova R, Kempton MJ, Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Borgwardt S. Progressive brain changes in schizophrenia related to antipsychotic treatment? A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013; 37: 1680–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D, Cavanagh J, Gerber D, Lawrie SM, Ebmeier KP, McIntosh AM. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 195: 194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempton MJ, Geddes JR, Ettinger U, Williams SC, Grasby PM. Meta-analysis, database, and meta-regression of 98 structural imaging studies in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008; 65: 1017–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesli M, Egeland R, Sønderby IE, Haukvik UK, Bettella F, Hibar DP et al. No evidence for association between bipolar disorder risk gene variants and brain structural phenotypes. J Affect Disord 2013; 151: 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CS, Baldessarini RJ, Vieta E, Yucel M, Bora E, Sim K. Longitudinal neuroimaging and neuropsychological changes in bipolar disorder patients: review of the evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013; 37: 418–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy A, Horrocks J, Doucette S, Keown-Stoneman C, McCloskey S, Grof P. The developmental trajectory of bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 204: 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootsman F, Brouwer RM, Kemner SM, Schnack HG, van der Schot AC, Vonk R et al. Contribution of genes and unique environment to cross-sectional and longitudinal measures of subcortical volumes in bipolar disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015; 25: 2197–2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe C, Ekman CJ, Sellgren C, Petrovic P, Ingvar M, Landen M. Manic episodes are related to changes in frontal cortex: a longitudinal neuroimaging study of bipolar disorder 1. Brain 2015; 138(Pt 11): 3440–3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberg B, Rahm C, Panayiotou A, Pantelis C. Brain change trajectories that differentiate the major psychoses. Eur J Clin Invest 2016; 46: 658–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan TL, Butters N, Ditraglia G, Schafer K, Smith T, Riwin M et al. Reduced cerebral gray-matter observed in alcoholics using magnetic-resonance-imaging. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1991; 15: 418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karama S, Ducharme S, Corley J, Chouinard-Decorte F, Starr JM, Wardlaw JM et al. Cigarette smoking and thinning of the brain's cortex. Mol Psychiatry 2015; 20: 778–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen KN, Skjaervo I, Morch-Johnsen L, Haukvik UK, Lange EH, Melle I et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with thinner cingulate and insular cortices in patients with severe mental illness. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015; 40: 241–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N, Gasic GP, Kennedy DN, Hodge SM, Kaiser JR, Lee MJ et al. Cortical thickness abnormalities in cocaine addiction—a reflection of both drug use and a pre-existing disposition to drug abuse? Neuron 2008; 60: 174–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin S, Poupon C, Linke J, Wessa M, Phillips M, Delavest M et al. A multicenter tractography study of deep white matter tracts in bipolar I disorder: psychotic features and interhemispheric disconnectivity. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71: 388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai XJ, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Shinn AK, Gabrieli JD, Nieto Castanon A, McCarthy JM et al. Abnormal medial prefrontal cortex resting-state connectivity in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011; 36: 2009–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Swartz HA. A critical appraisal of neuroimaging studies of bipolar disorder: toward a new conceptualization of underlying neural circuitry and a road map for future research. Am J Psychiatry 2014; 171: 829–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rive MM, Mocking RJ, Koeter MW, van Wingen G, de Wit SJ, van den Heuvel OA et al. State-dependent differences in emotion regulation between unmedicated bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rive MM, Koeter MW, Veltman DJ, Schene AH, Ruhe HG. Visuospatial planning in unmedicated major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder: distinct and common neural correlates. Psychol Med 2016; 46: 2313–2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G, Green MJ, Breakspear M, McCormack C, Frankland A, Wright A et al. Reduced inferior frontal gyrus activation during response inhibition to emotional stimuli in youth at high risk of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2013; 74: 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanford LC, Sassi RB, Hall GB. Accuracy of emotion labeling in children of parents diagnosed with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2016; 194: 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S, Zilles K, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB. ALE meta-analysis of action observation and imitation in the human brain. Neuroimage 2010; 50: 1148–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneau M, Beaucousin V, Herve PY, Duffau H, Crivello F, Houde O et al. Meta-analyzing left hemisphere language areas: phonology, semantics, and sentence processing. Neuroimage 2006; 30: 1414–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M, Ladouceur C, Drevets W. A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2008; 13: 833–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception II: Implications for major psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54: 515–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL, Drevets WC. Neurocircuitry of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010; 35: 192–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fears SC, Service SK, Kremeyer B, Araya C, Araya X, Bejarano J et al. Multisystem component phenotypes of bipolar disorder for genetic investigations of extended pedigrees. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71: 375–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.