Abstract

Long chain fatty acids (LCFAs) exert pro-inflammatory effects in vivo. However, little is known regarding the effect of LCFAs on invariant (i) NKT cell functions. Here, we report an inhibitory effect of saturated LCFAs on transcription factors in iNKT cells. Among the saturated LCFAs, palmitic acid (PA) specifically inhibited IL-4 and IFN-γ production and reduced gata-3 and t-bet transcript levels in iNKT cells during TCR-mediated activation. In iNKT cells, PA was localized and induced dilation in the endoplasmic reticulum and increased the mRNA levels of downstream molecules of IRE1α RNase. Moreover, PA increased the degradation rates of gata-3 and t-bet mRNA, which was restored by IRE1α inhibition or transfection with mutant gata-3 or t-bet, indicating that gata-3 and t-bet are cleaved via regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD). A PA-rich diet and PA injection suppressed IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells in C57BL/6, but not Jα18 knockout mice, which was restored by injection of STF083010, an IRE1α-specific inhibitor. Furthermore, a PA-rich diet and PA injection attenuated arthritis in an iNKT cell-dependent manner. Taken together, our experiments demonstrate that a saturated LCFA induced RIDD-mediated t-bet and gata-3 mRNA degradation in iNKT cells, thereby suppressing arthritis.

Introduction

Long chain fatty acids (LCFAs) are an abundant component of the Western diet and are proposed to induce various diseases including metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and inflammatory diseases. LCFAs are fatty acids that have aliphatic tails of 13 to 21 carbons and are classified as saturated and unsaturated, depending on their carbon- carbon single bond and double bond content. It has been shown that the structures, metabolism, and biological effects of LCFAs in vivo are very unique, and the absorption efficiency of dietary LCFAs depends on carbon chain length1. Moreover, restriction of saturated LCFA intake reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases, as they promote inflammation in various organs1. In contrast, the American Heart Association recommends intake of unsaturated LCFA-rich foods for prevention of cardiovascular diseases based on the anti-inflammatory effects of LCFAs2. Thus, a biological balance between saturated and unsaturated LCFAs might be important for regulating various physiological and pathological events in vivo.

Several studies have reported that LCFAs affect various immune cell functions. O’Sullivan et al. demonstrated that de novo fatty acid synthesis was indispensable for the Th17 and regulatory T cell differentiation of CD4+ T cells, as well as the survival of CD8+ T cells3,4, indicating that intracellular fatty acid synthesis modulates certain functions of conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Moreover, among the exogenous LCFAs, palmitic acid upregulated the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 via NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages5 and activated dendritic cells to secret IL-1β in a toll-like receptor (TLR)4-dependent manner, thereby amplifying Th1/Th17 immune responses and inflammation6,7. These findings indicate that both intracellular fatty acids and extracellular LCFAs affect the functions of immune cells in vitro and in vivo.

Invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells are a subset of T cells characterized by their recognition of the CD1d glycolipid antigen and their expression of the semi-invariant Vα14-Jα18 TCR8. α-galactosyl ceramide (α-GalCer), a glycolipid derived from a marine sponge activates iNKT cells in vitro and in vivo 9. Upon stimulation via TCR engagement, iNKT cells rapidly secrete large amounts of various cytokines, thereby playing an important role in the regulation of inflammatory diseases10,11. However, it has not been reported whether de novo fatty acids or extracellular saturated and unsaturated LCFAs affect the function of innate T cells including iNKT cells. Thus, we investigated effects of extracellular saturated and unsaturated LCFAs on iNKT cell function in vitro and in vivo. Our experiments demonstrate that saturated LCFAs inhibit IL-4 and IFN-γ production in iNKT cells by promoting t-bet and gata-3 mRNA degradation via regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD), thereby attenuating iNKT cell-mediated joint inflammation.

Results

Palmitic acid inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ, but not IL-2, IL-10, IL-13, or IL-17, production by iNKT cells in vitro

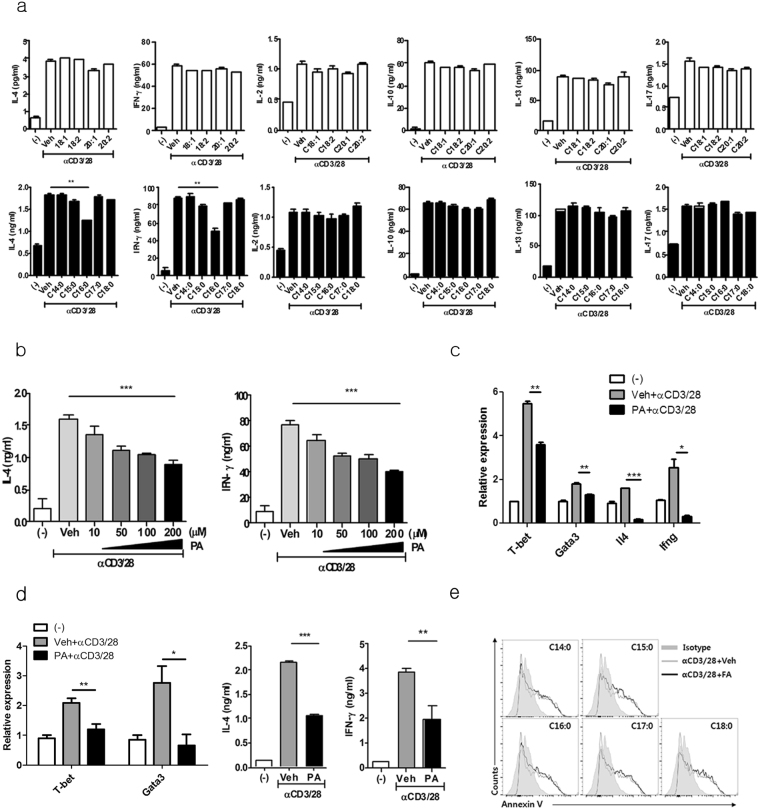

To investigate whether saturated and unsaturated LCFAs regulate the function of iNKT cells, we treated mouse iNKT cell line with various saturated and unsaturated LCFAs in the presence of anti-CD3 and CD28 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or α-GalCer-loaded bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). Among the saturated LCFAs, only palmitic acid (C16:0) inhibited IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cell line in a dose-dependent manner, whereas it did not alter production of IL-2, IL-10, IL-13, and IL-17 (Fig. 1a and b, Supplementary Fig. 1). Kinetic analysis revealed that palmitic acid gradually reduced IL-4 and IFN-γ, but not IL-2, IL-10, IL-13, and IL-17 levels in the culture supernatant (Supplementary Fig. 2a). In contrast, no unsaturated LCFAs affect the production of any of the cytokines evaluated in the iNKT cell line (Fig. 1a). Palmitic acid reduced the mRNA levels of Ifng and Il4 as well as those of their signature transcription factors such including t-bet and gata-3 upon TCR stimulation (Fig. 1c). Consistent with these iNKT cell line experiments, the palmitic acid-induced inhibition of IL-4 and IFN-γ production and reductions in t-bet and gata-3 mRNA expression levels were also found in CD1d/α-GalCer+ iNKT cells sorted from liver mononuclear cells of C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1d). However, palmitic acid did not affect apoptosis in the iNKT cell line in the presence of TCR stimulation (Fig. 1e). These findings suggest that palmitic acid, a saturated LCFA, inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ production by suppressing t-bet and gata-3 mRNA levels in iNKT cells upon TCR stimulation.

Figure 1.

Palmitic acid (C16: 0), a saturated long chain fatty acid (LCFA), inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ, but not IL-2, IL-10, IL-13, or IL-17 production by iNKT cells. (a) The levels of cytokines were measured in culture supernatants from an iNKT cell line treated with various saturated or unsaturated LCFAs in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for 24 h. (b) The levels of IL-4 and IFN- γ in supernatant of iNKT cell line treated with various concentrations of palmitic acid (C16:0) in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAb for 24 h. (c) The transcript levels of t-bet, gata-3, Il4, and Ifng were measured in the iNKT cell line. (d) α-GalCer/CD1d tetramer + TCRβ + iNKT cells were sorted from C57BL/6 mouse liver mononuclear cells and treated with palmitic acid and anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs for 24 h. The levels of t-bet and gata-3 mRNA were measured in these cells, while IL-4 and IFN-γ levels were estimated in culture supernatants. (e) The expression levels of Annexin V in iNKT cells treated with various saturated LCFAs in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Palmitic acid is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and induces ER stress in iNKT cells

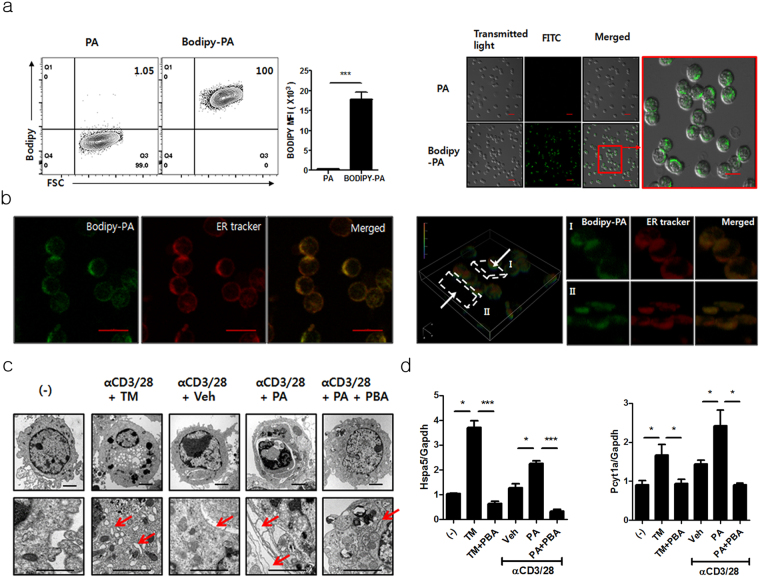

To investigate the mechanisms by which palmitic acid inhibited IL-4 and IFN-γ production in iNKT cells, the iNKT cell line was treated with Bodipy-conjugated palmitic acid. Flow cytometry and confocal microscopic examination revealed that palmitic acid was located in the cytoplasm rather than in membrane or nucleus (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, on confocal microscopic examination, palmitic acid was localized in the ER compartment (Fig. 2b), suggesting that it may regulate cellular function by modifying ER homeostasis. Consistently, electron microscopic examination revealed palmitic acid-induced dilation and elongation of the ER (Fig. 2c), and we also found increased transcription levels of ER chaperone BiP (Hspa5) and enzyme involved in ER dilation CCTα (Pcyt1a) in iNKT cells upon TCR stimulation (Fig. 2d). These results were similar to those obtained from iNKT cells treated with tunicamycin, a potent ER stress inducer (Fig. 2c and d). Moreover, an ER stress inhibitor, 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) restored palmitic acid-induced dilation of the ER and reduced the transcription levels of Hspa5 and Pcyt1a in iNKT cells (Fig. 2d). These results indicate that influx of palmitic acid into the cytoplasm induces ER modulation in iNKT cells during TCR stimulation.

Figure 2.

Palmitic acid was localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in iNKT cells, and it induced ER stress. (a) iNKT cells were treated with Bodipy-conjugated or unconjugated palmitic acid for 2 min and were analyzed using flow cytometry or confocal microscopy. The bars indicate 20 μm and 10 μm in low- and high-power images, respectively. (b) Z-stacks were used for three-dimensional reconstruction of iNKT cells treated with Bodipy-conjugated palmitic acid and an ER tracker under confocal microscopic examination. The bars indicate 10 μm. (c and d) Upon stimulation with anti-CD3 and CD28 mAbs, (c) electron microscopic examination was performed, and (d) the levels of Hspa5 and Pcyt1 mRNA were measured in the iNKT cells treated with tunicamycin or palmitic acid in the presence or absence of 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA). The bars and arrows indicate 2 μm and ER, respectively. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005.

Palmitic acid-mediated ER stress suppresses IL-4 and IFN-γ in iNKT cells via the IRE1α pathway

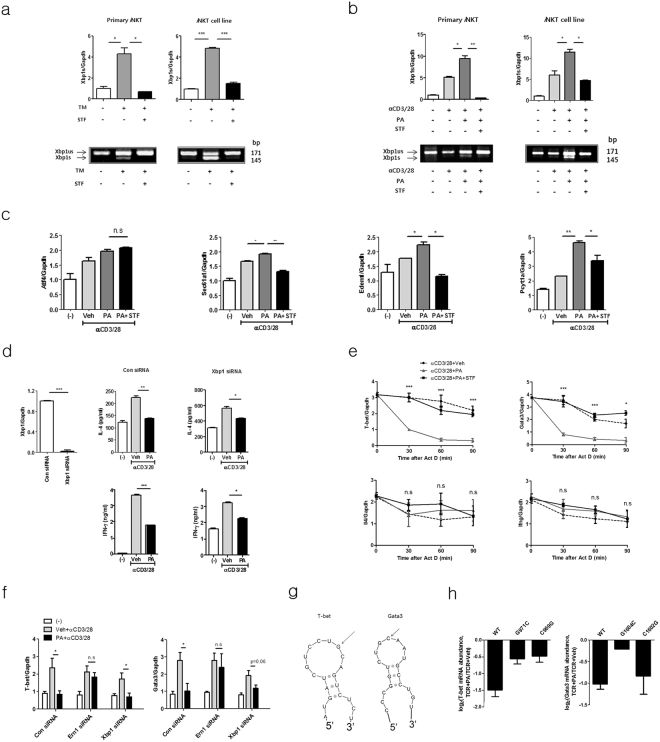

During ER stress, three transmembrane proteins, protein kinase R-like ER-localized eIF2α kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme-1 (IRE-1), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), are typically activated in mammalian cells12. Thus, to explore the activation pathways involved in palmitic acid-mediated inhibition of IL-4 and IFN-γ production in iNKT cells, we knocked down these molecules by siRNA transfection in the iNKT cell line (Fig. 3a). Among the three ER stress activation molecules, knockdown of IRE1α (Ern1) restored IL-4 and IFN-γ production during TCR stimulation, whereas down-regulation of PERK (Eif2ak3) and ATF6 (Atf6) did not affect the levels of these cytokines compared with controls (Fig. 3b). These findings indicate that the IRE1α pathway is involved in palmitic acid-induced inhibition of IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells. Consistent with this, STF083010, an IRE1α-specific inhibitor, restored the production of IL-4 and IFN-γ as well as mRNA levels of t-bet and gata-3 in iNKT cells treated with palmitic acid in the presence of TCR stimulation (Fig. 3c and d). It has been reported that ER stress-induced activation of IRE1α exerts endonuclease activity on various mRNAs, including xbp-1, thereby generating the spliced form of XBP1(Bettigole and Glimcher, 2015). Thus, we measured the mRNA levels of spliced xbp-1 in iNKT cells treated with palmitic acid and/or anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. Similar to tunicamycin treatment, palmitic acid treatment in the presence of TCR stimulation increased the transcription of spliced xbp-1 in the iNKT cell line and in sorted iNKT cells (Fig. 4a and b). Moreover, STF083010 reduced transcription levels of spliced xbp-1 in palmitic acid and tunicmycin-treated iNKT cells (Fig. 4a and b). Consistent with these results, in iNKT cells, palmitic acid in the presence of TCR stimulation gradually increased the expression levels of the molecules downstream of spliced XBP1, including Sec 61a1, Edem1, and Pcyt1a, which were also decreased by STF083010 (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 2b). In contrast, mRNA levels of ATF4-related genes were increased, peaked at 8 h, and abruptly decreased, which was not consistent with cytokine production (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Altogether, these results indicate that palmitic acid inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ production by activating the IRE1α pathway in the ER of iNKT cells.

Figure 3.

Palmitic acid-mediated ER stress suppresses IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells via the IRE1α pathway. (a and b) iNKT cells were transfected with siRNA for control, Eif2ak3, Ern1, or Atf6 and treated with palmitic acid or vehicle in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs for 24 h. (a) The efficiency of knockdown was estimated for each individual gene. (b) The levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ were measured in culture supernatants using ELISA. (c and d) iNKT cells were incubated with palmitic acid or vehicle in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs for 24 h. To inhibit IRE1α, STF083010 was added during palmitic acid treatment. (c) The levels of cytosolic IL-4 and IFN- γ were estimated using cytometric analysis. (d) The transcription levels of t-bet and gata-3 were measured in the iNKT cell line using real time PCR, while the levels of IL-4 and IFN- γ were quantified using ELISA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Figure 4.

Palmitic acid promotes the degradation of t-bet and gata-3 mRNA in iNKT cells via regulated IRE1α-dependent decay (RIDD), thereby suppressing IL-4 and IFN- γ production. (a and b) iNKT cells or α-GalCer/CD1d tetramer + TCRβ + iNKT cells sorted from C57BL/6 mouse liver mononuclear cells were treated with (a) tunicamycin (TM) and/or STF083010 or (b) palmitic acid and/or STF083010 in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. Reverse-transcription PCR and real-time PCR were performed to estimate un-spliced (us) or spliced (s) xbp-1. (c) The expression levels of Sec 61a1, Edem1, Pcyt1a and Atf4 were also measured in iNKT cells using real-time PCR. (d) To knock-down xbp-1, iNKT cells were transfected with control or xbp-1 siRNA and then treated with palmitic acid or vehicle in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs for 24 h. The levels of IL-4 and IFN- γ were estimated in culture supernatants using ELISA. (e) The transcription levels of t-bet, gata-3, Il4, and Ifng were estimated in iNKT cells treated with vehicle, palmitic acid, or palmitic acid and STF083010 in the presence of actinomycin D at the indicated time points. (f) The transcription levels of t-betand gata-3 were measured in Ern1- or xbp-1-knockdown or control iNKT cells upon treatment with vehicle, palmitic acid, or palmitic acid and STF083010. (g) mRNA structural modeling for t-bet and gata-3. (h) DN32.D3 cells were transfected with mutant t-bet (G971C or C969G), mutant gata-3 (G1604C or C1602G), or wild type t-bet and gata-3 and then treated with palmitic acid or vehicle in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. mRNA measurement reflects the amount of relative degradation of t-bet or gata-3 transcript. n.s. not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Palmitic acid induces degradation of t-bet and gata-3 mRNA via RIDD, thereby suppressing IL-4 and IFN-γ production in iNKT cells

Our experiments demonstrated that palmitic acid activated both IRE1α and XBP1 in iNKT cells in the presence of TCR stimulation. Thus, to determine which of the protein directly regulates the palmitic acid-induced inhibition of IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells, we knocked downed IRE1α and XBP1 in the iNKT cell line using siRNA. In contrast to IRE1α (Fig. 3b), knockdown of xbp-1 did not alter palmitic acid-induced inhibition of IL-4 and IFN-γ production in iNKT cells treated with anti-CD3 and CD28 mAbs (Fig. 4d). These results indicate that activation of IRE1α rather than XBP1 plays a critical role in palmitic acid-induced inhibition of IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells. Furthermore, IRE1α exerts RNase activity to regulate cellular functions by degrading various mRNA molecules via RIDD during ER stress13,14. To explore whether palmitic acid suppresses IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells via RIDD, iNKT cells were treated with actinomycin D in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. Interestingly, palmitic acid significantly decreased the transcript levels of t-bet and gata-3, but not Ifng and Il4 in iNKT cells compared with the control group, and these levels were restored by STF083010 treatment (Fig. 4e). Consistent with these results, knockdown of Ern 1 restored t-bet and gata-3 transcript levels in iNKT cells treated with palmitic acid and anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs compared with control siRNA-treated iNKT cells; however, xbp-1 knockdown did not affect reduction of two molecules (Fig. 4f). Generally, the target cleavage sites of the endonuclease IRE1α are located in the small stem loop of hairpin structures13,14. Structural mRNA modeling demonstrated that both t-bet and gata-3 contain an IRE1α-cleavage site in the loop of a hairpin structure (Fig. 4g). To confirm this, we transfected DN32.D3 cells, a NKT cell hybridoma, with wild type (WT) or mutated t-bet and gata-3 as described15. Palmitic acid suppressed t-bet and gata-3 transcript levels in DN32.D3 cells transfected with WT t-bet or gata-3 compared with vehicles. In contrast, palmitic acid minimally inhibit transcript levels of t-bet or gata-3 in DN32D.3 cells transfected with two types of t-bet mutant (G971C or C969G) or a gata-3 mutant (G1604C), but did those of gata-3 in cells transfected with C1602G-mutated gata-3. These findings suggest that t-bet and gata-3 are palmitic acid-mediated RIDD substrate in iNKT cells (Fig. 4h). Combined, these findings indicate that palmitic acid inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ production by degrading t-bet and gata-3 mRNA via RIDD in iNKT cells.

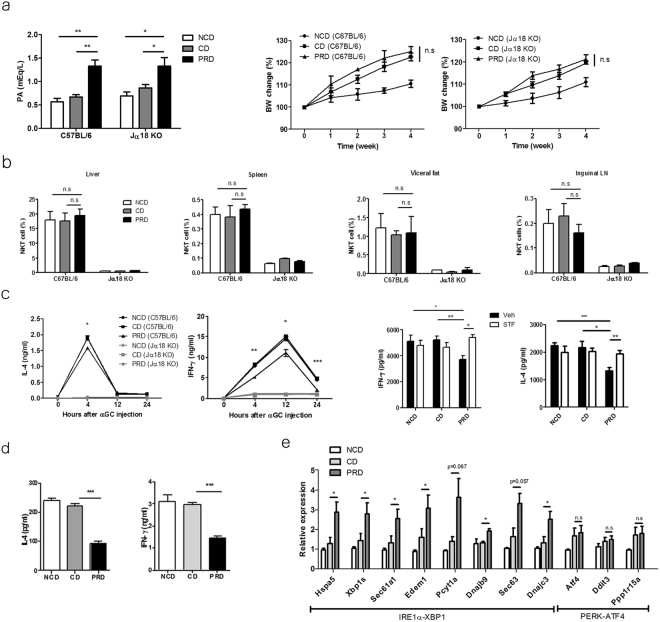

Palmitic acid inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells upon TCR stimulation via ER stress in vivo

To explore whether palmitic acid inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells in vivo, we injected C57BL/6 mice with bovine serum albumin (BSA)-conjugated palmitic acid. The serum levels of palmitic acid peaked at 4 h, after which they decreased gradually (Supplementary Fig. 3a), and the majority of hepatic iNKT cells contained Bodipy-conjugated palmitic acid in the cytosol (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The expression levels of Hspa5, spliced xbp-1, Sec 61a1, Edem1, Pcyt1a, Dnajb9, Sec 63, and Dnajc3 were increased in iNKT cells obtained from tunicamycin or palmitic acid-injected C57BL/6 mice (Supplementary Fig. 3c and d). Upon STF083010 injection, the increased levels of these molecules were suppressed in iNKT cells obtained from palmitic acid-injected C57BL/6 mice. In contrast, the transcript levels of Atf4, Ddit3, and Ppp1r15a were not altered in hepatic iNKT cells from C57BL/6 mice injected BSA-conjugated palmitic acid (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Moreover, the serum levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ were lower in C57BL/6, but not in Jα18 knockout (KO), mice injected with BSA-conjugated palmitic acid compared with mice treated with vehicle 4 h after α-GalCer administration. Injection of STF083010 restored IL-4 and IFN-γ levels (Supplementary Fig. 3e and f). Altogether, these findings indicate that palmitic acid inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells via ER stress in C57BL/6 mice. To confirm the effect of palmitic acid on iNKT cell functions under physiological conditions in vivo, C57BL/6 and Jα18 KO mice were fed a palmitic acid-rich diet (PRD) or a control diet (CD), which contained minimal levels of palmitic acid but a similar numbers of calories as those of the PRD. The body weight of the mice and the numbers and tissue distribution of iNKT cells were similar between the two treatment groups; however, the levels of palmitic acid were higher in the serum of C57BL/6 and Jα18 KO mice fed a PRD compared with those fed the CD or normal chow diet (NCD) (Fig. 5a and b). Injection of α-GalCer resulted in lower serum levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ in C57BL/6 mice fed the PRD compared with mice fed the CD, which was restored by STF083010 injection; however, these results were not found in Jα18 KO mice (Fig. 5c). Upon stimulation with α-GalCer, mononuclear cells from the livers of C57BL/6 mice fed the PRD produced less IL-4 and IFN-γ than did those from mice fed the CD (Fig. 5d). Moreover, the expression levels of Hspa5, spliced xbp-1, Sec 61a1, Edem1, Pcyt1a, Dnajc3, Sec 63, and Dnajc3 were increased in iNKT cells obtained from C57BL/6 mice fed the PRD compared with mice fed the CD, whereas levels of Atf4, Ddit3, and Ppp1r15a transcript were not altered (Fig. 5e). These findings indicate that dietary palmitic acid induces ER stress in iNKT cells in vivo, thereby inhibiting IL-4 and IFN-γ production.

Figure 5.

Dietary palmitic acid inhibits IL-4 and IFN- γ production by iNKT cells via ER stress in the presence of TCR stimulation in vivo. (a) Serum levels of palmitic acid were estimated in C57BL/6 mice fed a normal chow diet (NCD), palmitic acid-rich diet (PRD), or a control diet (CD) for 4 weeks. The CD contained similar amount of calories as those of the PRD, but minimal palmitic acid. The serum concentration of palmitic acid and body weight of C57BL/6 and Jα18 Knockout (KO) mice were measured. (b) The percentages of iNKT cells in the visceral fat, liver, spleen, and inguinal lymph nodes were analyzed. The levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ in (c) the serum of C57BL/6 or Jα18 KO mice fed the NCD, CD, or PRD in the presence of (right panel) or absence (left panel) intraperitoneal STF083010 (20 mg/kg) injection every week for 4 weeks after α-GalCer injection and in (d) the supernatant of hepatic mononuclear cells from these mice in the presence of α-GalCer. (e) The expression levels of Hspa5, spliced xbp-1, Sec 61a1, Edem1, Pcyt1a, Dnajb9, Sec 63, Dnajc3, Atf4, Ddit3, and Ppp1r15a in hepatic iNKT cells obtained from C57BL/6 mice fed the NCD, CD, or PRD for 1 week using real time PCR. n = 12 per group in a; n = 6 per group in b, d and e; n = 9 per group in c. Data were pooled from three independent experiments and analyzed. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Dietary palmitic acid attenuates antibody-induced joint inflammation by inhibiting IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells

To confirm the inhibitory effect of palmitic acid on IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells in a disease model, we induced joint inflammation in C57BL/6 and Jα18 KO mice via administration of K/BxN serum and subsequently treated these mice with palmitic acid or vehicle. Compared with controls, injection with BSA-conjugated palmitic acid attenuated joint inflammation in C57BL/6 mice but not in Jα18 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). Moreover, adoptive transfer of iNKT cells into Jα18 KO mice restored joint inflammation, which was inhibited by injecting BSA-conjugated palmitic acid, but not vehicle. Injection of palmitic acid, compared with vehicle, decreased the levels of IL-4, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in joint tissues in C57BL/6 and Jα18 KO mice with adoptive iNKT cell transfer, whereas it increased TGF-β levels in the joints of these mice (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Consistently, PRD-fed C57BL/6 mice showed less joint inflammation compared with mice fed a CD or NCD. In contrast, attenuation of joint inflammation was not detected in Jα18 KO mice fed the PRD compared with those fed the CD or NCD (Fig. 6a–c). Higher levels of IL-4, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, but lower levels of TGF-β, were detected in joint tissues of C57BL/6 mice fed the CD or NCD compared with those fed the PRD. However, the PRD did not alter cytokine levels in the joints of Jα18 KO mice (Fig. 6d). Consistent with the effect of palmitic acid on arthritis, tunicamycin also suppressed joint inflammation in C57BL/6 mice, but not in Jα18 KO mice (Fig. 7). Moreover, joint inflammation was similarly developed in C57BL/6 mice fed NCD, CD, or PRD for 4 weeks, and then continuously NCD for 2 weeks, suggesting that suppressive effect of palmitic acid on iNKT cell function might be reversible (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d). Taken together, these results indicate that dietary palmitic acid suppresses joint inflammation by inhibiting IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells.

Figure 6.

Dietary palmitic acid suppresses antibody-induced joint inflammation by inhibiting IL-4 and IFN-γ production. (a–d) C57BL/6 and Jα18 KO mice were fed a NCD, CD, or PRD for 6 weeks, and joint inflammation was induced by K/BxN serum injection. (a) The ankle thickness and clinical scores were measured during antibody-induced arthritis. (b) The gross and microscopic images of the ankles of these mice are presented. The bars indicate 2 mm. (c) The histological scores of joint inflammation were measured. (d) The expression levels of Il4, Ifng, Tnf, and Tgfb1 were measured in the joints of these mice during antibody-induced arthritis. n = 10 per group in a–d. Data were pooled from two independent experiments and analyzed. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Figure 7.

An ER stress inducer tunicamycin, suppresses antibody-induced joint inflammation by inhibiting IL-4 and IFN-γ production. (a–c) C57BL/6 and Jα18 KO mice were injected with tunicamycin (0.3 mg/kg) every 5 days (days 0 and 5), and joint inflammation was induced by K/BxN serum injection. (a) The ankle thickness and clinical scores were measured in C57BL/6 and Jα18 KO mice during antibody-induced arthritis. (b) The gross images of the ankles of these mice are presented. (c) The expression levels of Il4, Ifng, Tnf, andTgfb1 were measured in the joints of these mice during antibody-induced arthritis. n = 10 per group in a–c. Data were pooled from two independent experiments and analyzed. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Discussion

A growing body of evidence indicates the inflammatory effects of the saturated LCFA palmitic acid on various cell types and in many diseases. Several studies have demonstrated that palmitic acid promotes inflammatory processes in islet β cells and macrophages via the TLR4/MyD88 pathway and NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation, thereby affecting insulin sensitivity5,16. This palmitic acid-induced inflammatory response was synergistically induced with lipopolysaccharide via de novo ceramide biosynthesis in macrophages17. Moreover, palmitic acid also acts as a pro-inflammatory factor in various diseases including arthritis, atherosclerosis, and hypothalamic dysregulation18–20. In particular, palmitic acid upregulated IL-6 in human chondrocytes and fibroblast-like synovial cells via TLR4 signaling in an arthritis model18. In contrast to this pro-inflammatory effect, our experiments clearly demonstrated that palmitic acid attenuated antibody-induced arthritis by inducing ER stress in iNKT cells. Thus, opposing effects of palmitic acid on inflammation suggest that palmitic acid exerts different effects depending on the microenvironment of the target and on the cell types and signaling pathways involved.

Among the immune cells, T cells increase the ER stress-associated unfolded protein response (UPR) and expression levels of GRP78 in a Ca2+-dependent manner during TCR-mediated activation21,22. Furthermore, GRP78 deficiency reduces the proliferation of granzyme B-mediated cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells23. These findings indicate that ER stress modulates the function and viability of conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. However, it is not known whether the metabolic microenvironment affects the function of immune cells by modulating ER homeostasis, particularly in innate T-lineage iNKT cells. Our experiments demonstrated that extracellular palmitic acid is translocated into the cytosol and localized in the ER, and that it induces elongation of the ER and increased the expression levels of GRP78 (also known as BiP) in activated iNKT cells. Moreover, palmitic acid inhibited IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells in the presence of TCR stimulation. Consistent with these results, the transcription levels of gata-3 and t-bet in activated iNKT cells were reduced by palmitic acid treatment, suggesting that the expression of these transcription factors might be modulated by palmitic acid. Several studies have demonstrated that palmitic acid induces ER stress and promotes interaction of ATF4 and CREB1 with the atf4 promoter in non-immune cells via activation of the PERK pathway, thereby regulating cell death24–26. Moreover, palmitic acid attenuated leptin and insulin-like growth factor 1 expression in the brain by activating C/EBPa homologous protein (CHOP)27. These findings indicate that palmitic acid activates the PERK pathway, rather than IRE1α in non-immune cells during ER stress. In contrast to these results, palmitic acid affected the cytokine production by, but not the viability of, iNKT cells during TCR-mediated activation via IRE1α, but not the PERK pathway. IRE1α is the most conserved mediator of the UPR, which increases its C-terminal endoribonuclease activity via phosphorylation-induced conformation shifts, thereby inducing RIDD and generating spliced XBP1 (Bettigole and Glimcher, 2015). RIDD contributes to either preservation of ER homeostasis or induction of cell death by site specific degradation of ER-localized mRNAs (Maurel et al., 2014). In our experiments, palmitic acid enhanced IRE1α endonuclease-dependent degradation of t-bet and gata-3 mRNA, but not of Il4 and Ifng transcripts in iNKT cells. These results indicate that palmitic acid inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells via RIDD-mediated degradation of t-bet and gata-3 mRNA. Moreover, RIDD induces cleavage of mRNAs containing the XBP-1 consensus site in all species, and it is therefore considered as a sequence- and structure-specific cellular event13,14. In our study, structural modeling revealed that t-bet and gata-3 mRNA contain the XBP-1 consensus site in their hairpin structure loops (Fig. 4g). Thus, we here demonstrated that a saturated LCFA promotes degradation of t-bet and gata-3 mRNA in T-lineage cells via RIDD during TCR-mediated activation, resulting in suppression of IL-4 and IFN-γ production. These results suggest that extracellular metabolites can affect the transcriptional activity of target proteins in immune cells in vivo and highlight the implications of RIDD in the regulation of immune cells by inhibition of transcription factors. Furthermore, based on these results, we also hypothesize that palmitic acid might affect Th1 and/or Th2 cell differentiation in vivo, although further research is warranted to clarify this.

In our experiments, tunicamycin also suppressed IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells. Moreover, it has been reported that tunicamycin may act through palmitoylation as well as induction of ER stress28, which led to consider palmitic acid-mediated palmitoylation effect on iNKT cells in vitro and in vivo. However, palmitic acid increased the transcript levels of spliced xbp-1 and its downstream genes during TCR-mediated activation in iNKT cells, and this effect was reduced by treatment with an IRE1α-specific inhibitor. These results indicate that spliced XBP1 was activated in iNKT cells in the palmitic acid-induced ER response rather than palmitoylation. The IRE1α-mediated generation of spliced XBP1, a potent transcription factor, exerts critical effects on differentiation, lipid metabolism, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and the HIF-1α-dependent hypoxia pathway in various cell types12,29–31. However, the functional role of spliced XBP1 has not been well characterized in immune cells. Recent studies have demonstrated that XBP1 deficiency induces defects in eosinophil differentiation and functions of CD8+ and tumor-associated dendritic cells32–34, indicating that spliced XBP1 plays a critical role in development and function of immune cells. However, spliced XBP1 might be play a minimal role in palmitic acid-induced inhibition of IL-4 and IFN-γ production by iNKT cells, although the functional role of spliced XBP1 in iNKT cells remains unknown. In recent years, it has been reported that altered IRE1α function is associated with various diseases including cancers, diabetes, and inflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders35–37. Interestingly, ER stress-related gene signatures were increased in synovial cells in rheumatoid arthritis and in deficiency of GRP78-inhibited collagen-induced arthritis38, and deletion of IRE1α in myeloid cells protected mice from arthritis in a K/BxN serum transfer model37. Consistent with our results, these findings suggest that the IRE1α-mediated UPR in immune cells might be involved in the regulation of joint inflammation.

In conclusion, our experiments demonstrate that the saturated LCFA palmitic acid inhibits IL-4 and IFN-γ production in iNKT cells by promoting t-bet and gata-3 mRNA degradation via RIDD, thereby regulating iNKT cell-mediated diseases. This study highlights the effect of saturated LCFAs on iNKT cell-mediated immune regulation via ER stress in vivo.

Materials And Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice (7–8 weeks old) were purchased from Orient Company Ltd. (Seoul, Korea). Jα18-/- mice were a gift from Dr. M. Taniguchi (Chiba University, Chiba, Japan). KRN TCR transgenic mice and NOD mice, gifts from Drs. D. Mathis and C. Benoist (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA and the Institut de Genetique et de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Strasbourg, France), were maintained on a B6 background (K/B). Arthritic mice (K/BxN) were obtained by crossing K/B and NOD (N) mice. These mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Clinical Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital. All in vivo experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Clinical Research Institute, Seoul National University Hospital and conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Establishment of the primary NKT cell line and coculture with bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs)

The NKT cell line was established as reported previously39. Briefly, the sorted α-GalCer/CD1d tetramer+ TCRβ+ NKT cells from liver mononuclear cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 (3 μg/mL) and anti-CD28 antibodies (1 μg/mL) for 3 days and then expanded with mouse recombinant IL-2 (10 ng/mL) and IL-7 (10 ng/mL) (Peprotech) for 7 days in complete RPMI medium (10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/ streptomycin, 1% HEPES, 1% non-essential amino acid, 1% sodium pyruvate, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, and 1% L-glutamine). The culture media of iNKT cells were changed every 2–3 days, and all of the in vitro experiments were performed after at least 10 days of culture. RAW264.7 cells were maintained in DMEM (10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin). Generation of BMDCs and coculture with NKT cell line were performed as described previously40.

Antibodies and reagents

The antibodies and reagents used in the experiments were as follows: anti-CD3, anti-CD28, PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-TCR-β, anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-4, anti-IL-2, and anti-IL-10 antibodies (BD Bioscience); anti-IL-13 and anti-IL-17 antibodies (R&D Biosystems); BODIPY-PA (D-321) and ER tracker (E34250) (Thermo Fisher Scientific); STF083010 (cat # 4509) (Tocris Bioscience); and tunicamycin (T7765) and sodium phenylbutyrate (SML0309) (Sigma-Aldrich). The APC-conjugated and α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers were provided by the National Institute of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA).

Fatty acid preparation and analysis of serum fatty acids in mice

Myristic acid (C14:0, T0502), pentadecanoic acid (C15:0, P6125), palmitic acid (C16:0, P9767), margaric acid (C17:0, H3500), stearic acid (C18:0, S4751), oleic acid (C18:1, O1008), linoleic acid (C18:2, 62240), cis-11-eicosenoic acid (C20:1, E3635), and cis-11,14-eicosadienoic acid (C20:2, E3127) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. These LCFAs were conjugated with non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA)-free BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, a7030). Briefly, fatty acids were dissolved in sterile water using a vortex and heated to 70 °C for 10 min. Fatty acids were conjugated to BSA in serum-free RPMI containing 5% NEFA-free BSA immediately after dissolving as described previously41. The conjugated-fatty acids were shaken at 140 rpm at 40 °C for 1 h before adding to the cells. Serum-free RPMI containing 5% NEFA-free BSA was used as the vehicle control. To evaluate the effects of palmitic acid in vivo, mice were injected with palmitic acid (15 μM) conjugated to free NEFA-free BSA. The fatty acid concentration in mouse serum after palmitic acid injection was measured using the acyl-CoA synthetase-acyl-CoA oxidase method (HR series NEFA HR, Wako).

RNA isolation, real-time PCR, and XBP1 splicing assay

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, 15596–018), and cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). The following primers were used for real-time PCR: Tbx21 forward: 5′-TTCCCATTCCTGTCCTTCAC-3′, reverse: 5′-CCACATCCACAAACATCCTG-3′. GATA-3 forward: 5′-GGAAACTCCGTCAGGGCTA-3′, reverse: 5′-AGAGATCCGTGCAGCAGAG-3′; IRE1α forward: 5′-GCAACCATCCTTTTGGCAAAT-3′, reverse: 5′-AACAGTCAAGGTTGCAGGCG-3′; XBP1 forward: 5′-GACAGAGAGTCAAACTAACGTGG-3′, reverse: 5′-GTCCAGCAGGCAAGAAGGT-3′; spliced XBP1 forward: 5′-AAGAACACGCTTGGGAATGG-3′, reverse: 5′-CTGCACCTGCTGCGGAC-3′; BiP forward: 5′-TCATCGGACGCACTTGGAA-3′, reverse: 5′-CAACCACCTTGAATGGCAAGA-3′; CCTα forward: 5′-GATGAGCTAACGCACAACTTCAA-3′, reverse: 5′-GTGCTGCACGGCGTCATA-3′; Edem1 forward: 5′-AAGCCCTCTGGAACTTGCG-3′, reverse: 5′-AACCCAATGGCCTGTCTGG-3′; Dnajc3 Forward: 5′-GGCGCTGAGTGTGGAGTAAAT-3′, reverse: 5′-GCGTGAAACTGTGATAAGGCG-3′; Sec. 61a1 forward: 5′-CTATTTCCAGGGCTTCCGAGT-3′, reverse: 5′-AGGTGTTGTACTGGCCTCGGT-3′; Sec. 63 forward: 5′-ACCTCCTTCGTGGGGCTCATC-3′, reverse: 5′-AATATTTGGCTGGGGTTTTA-3′; PERK forward: 5′-GCGTCGGAGACAGTGTTTG-3′, reverse: 5′-CGTCCATCTAAAGTGCTGATGAT-3′; ATF4 forward: 5′-GAGCTTCCTGAACAGCGAAGTG-3′, reverse: 5′-TGGCCACCTCCAGATAGTCATC-3′; CHOP forward: 5′-GTCCCTAGCTTGGCTGACAGA-3′, reverse: 5′-TGGAGAGCGAGGGCTTTG-3′; GADD34 forward: 5′-GAGGGACGCCCACAACTTC-3′; reverse: 5′-TTACCAGAGACAGGGGTAGGT-3′; ATF6α forward: 5′-TTATCAGCATACAGCCTGCG-3′, reverse: 5′-CTTGGGACTTTGAGCCTCTG-3′; GAPDH forward: 5′-GGGAAGCTCACTGGCATGG-3′, reverse: 5′-CTTCTTGATGTCATCATACTTGGCAG-3′. For the XBP1 splicing assay, cDNA was synthesized from purified total RNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, cat # 4368814). To evaluate the relative splicing of XBP1, RT-PCR was performed using the following primers to detect unspliced and spliced XBP1: forward: ACACGCTTGGGAATGGACAC, reverse: CCATGGGAAGATGTTCTGGG. Primers and probes for IL-4 (Mm00445259_m1), IFN-γ (Mm01168134_m1), TGF-β (Mm01178820M1), and TNF-α (Mm00443258_m1) were synthesized by Applied Biosystems. The levels of mRNA were normalized to those of GAPDH.

Generation of mutagenesis and transfection

To validate the specific nucleotides on t-bet and gata-3 mRNAs were required for RIDD, Wild-type and mutant form of t-bet (G971C C969G), gata-3 (G1604C, C1602G) were cloned into the pIRES3-puro vector (Clontech). 1 μg of cloned plasmid vectors were transfected into DN32.D3 cells, a NKT cell hybridoma using electroporation (Neon transfection system, Invitrogen) under condition of 1100 V, 30ms. We allowed cells to overexpress cloned genes for 48 h and treated anti-CD3 + CD28 antibodies and palmitic acid or vehicle. We analyzed altered gene expression after 24 h after treatment using primers designed to recognize the sequence that include mutated region. The primers used for real-time PCR are following: Tbx21 forward: 5′-CAGGAAGTTTCATTTGGGAAG -3′, reverse: 5′-GCTGGTACTTGTGGAGAG-3′. GATA-3 forward: 5′-GAGGAGGAACGCTAATGG -3′, reverse: 5′-GATGCCTTCTTTCTTCATAGTC -3′.

Diet compositions and feeding regimens

The CD and PRD were customized for the purpose of these experiments. The PRD contained higher levels of palmitic acid, but similar calories compared with those of the CD. The PRD was generated by adding palm oil (200 g/kg) to NCD (Purina), and thus palmitic acid comprised 47% of the total fat content in this diet. The CD was generated by adding medium-chain triglyceride oil (176 g/kg), safflower oil, and linoleic (24 g/kg), but minimal palmitic acid, to the NCD. The lipid content of the CD was determined according to the diet composition guide of Harlan Teklad (TD.05237, TD05235). The diet-fed mice were housed in a controlled environment that provided free access to water and chows. Eight-week-old mice were fed these diets for 1, 4, or 6 weeks, depending on the experiment.

Confocal microscopic examination

The iNKT cell line was treated with 2 μM Bodipy-conjugated palmitic acid mixed with 1 × Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 0.1% fatty acid-free albumin for 2 min, washed with cold wash solution (1 × HBSS containing 0.2% fatty acid-free albumin), and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min using cytocentrifuge (Wescor). Images were acquired using a laser-scanning confocal microscope A1 (NIKON). Three-dimensional image acquisition was performed using a Z-stack on each 0.40 μM panel and three-dimensional reconstruction was achieved using the NIS-Elements viewer.

Electron microscopic examination

Cell pellets were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 for 1 h at room temperature, washed, fixed in 2% OsO4 in 0.1 M phosphate or cacodylate buffer for 1.5 h at room temperature before embedding, and embedded with only epoxy resin. Thin sections were generated using an ultramicrotome (RMC MT-XL) and collected on a copper grid. The appropriate areas for thin sectioning were cut at 65 nm and stained with saturated 6% uranyl acetate and 4% lead citrate before examination using a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1400; Japan) at 80 kV.

Knockdown of target genes using siRNA

Cells were transiently transfected with siRNAs targeting PERK (Sigma, NM_010121), IRE1α (Sigma, NM_023913), ATF6α (Sigma, NM_001081304), and XBP1 (Sigma, NM_013842) using the Neon transfection system (Invitrogen) under transfer conditions of 1100 V and 30 ms.

mRNA stability assay and prediction of RNA secondary structures

To analyze mRNA stability, cells were treated with actinomycin D (Sigma, 5 μg/mL) at the indicated time points and then harvested for quantitative RT-PCR. To predict RNA secondary structures, we used a RNA secondary structure prediction tool (Sfold software) for statistical analysis of nucleic acid folding and studies of regulatory RNAs.

K/BxN serum transfer and arthritis scoring

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 80 μL pooled K/BxN serum on days 0 and 2. Ankle thickness was measured using calipers (Manostat). Jα18 KO mice were intravenously injected with the sorted hepatic iNKT cells from C57BL/6 mice 1 day before administering K/BxN serum. Joint swelling was monitored and scored as reported previously10.

Histological examination

Whole knee joints and paws were collected 10 days after K/BxN serum transfer, fixed in 10% formalin, decalcified, and paraffin embedded. Sections were prepared from the joint tissue blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Microscopic evaluation was performed by two independent observers who were blinded to the experimental conditions. The degree of histological inflammation was scored according to inflammatory cell infiltration, fibroblastic proliferation, synovial hyperplasia, pannus formation, intra-articular exudate, and bony erosion. A semi-quantitative three point scale was developed, with a score of 0 representing the lowest feature level and a score of 2 representing the highest feature level. The score for each parameter was assigned, and the total scores were used for comparison.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was analyzed using the Prism software (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). The unpaired two-tailed t-test was performed to compare groups. A value P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI14C1277). J.S.K. received a scholarship from the BK21-plus education program provided by the National Research Foundation of Korea. We would like to thank the Hyehwa Forum members for their helpful discussions and the NIH Tetramer Core Facility for providing the CD1d tetramers.

Author Contributions

J.S.K. and J.M.K. designed and performed experiments; J.S.S., Y.K.J., H.Y.K. interpreted data; D.H.C. designed, interpreted data, and wrote manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-14780-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Flock MR, Kris-Etherton PM. Diverse physiological effects of long-chain saturated fatty acids: implications for cardiovascular disease. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2013;16:133–140. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328359e6ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fenton JI, Hord NG, Ghosh S, Gurzell EA. Immunomodulation by dietary long chain omega-3 fatty acids and the potential for adverse health outcomes. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids. 2013;89:379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Sullivan D, et al. Memory CD8( + ) T cells use cell-intrinsic lipolysis to support the metabolic programming necessary for development. Immunity. 2014;41:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berod L, et al. De novo fatty acid synthesis controls the fate between regulatory T and T helper 17 cells. Nat Med. 2014;20:1327–1333. doi: 10.1038/nm.3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen H, et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weatherill AR, et al. Saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids reciprocally modulate dendritic cell functions mediated through TLR4. J Immunol. 2005;174:5390–5397. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stelzner K, et al. Free fatty acids sensitize dendritic cells to amplify TH1/TH17-immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:2043–2053. doi: 10.1002/eji.201546263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burdin N, et al. Selective ability of mouse CD1 to present glycolipids: alpha-galactosylceramide specifically stimulates V alpha 14 + NK T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:3271–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HY, et al. NKT cells promote antibody-induced joint inflammation by suppressing transforming growth factor beta1 production. J Exp Med201, 41-47 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Taniguchi M, Harada M, Kojo S, Nakayama T, Wakao H. The regulatory role of Valpha14 NKT cells in innate and acquired immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:483–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bettigole SE, Glimcher LH. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:107–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oikawa D, Tokuda M, Hosoda A, Iwawaki T. Identification of a consensus element recognized and cleaved by IRE1 alpha. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:6265–6273. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maurel M, Chevet E, Tavernier J, Gerlo S. Getting RIDD of RNA: IRE1 in cell fate regulation. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2014;39:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore K, Hollien J. Ire1-mediated decay in mammalian cells relies on mRNA sequence, structure, and translational status. Molecular biology of the cell. 2015;26:2873–2884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-02-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eguchi K, et al. Saturated fatty acid and TLR signaling link beta cell dysfunction and islet inflammation. Cell metabolism. 2012;15:518–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schilling JD, et al. Palmitate and lipopolysaccharide trigger synergistic ceramide production in primary macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:2923–2932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frommer KW, et al. Free fatty acids: potential proinflammatory mediators in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:303–310. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afonso MS, et al. Dietary interesterified fat enriched with palmitic acid induces atherosclerosis by impairing macrophage cholesterol efflux and eliciting inflammation. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry. 2016;32:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benoit SC, et al. Palmitic acid mediates hypothalamic insulin resistance by altering PKC-theta subcellular localization in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2577–2589. doi: 10.1172/JCI36714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takano S, et al. T cell receptor-mediated signaling induces GRP78 expression in T cells: the implications in maintaining T cell viability. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2008;371:762–766. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pino SC, et al. Protein kinase C signaling during T cell activation induces the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Cell stress & chaperones. 2008;13:421–434. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0038-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang JS, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress response promotes cytotoxic phenotype of CD8alphabeta + intraepithelial lymphocytes in a mouse model for Crohn’s disease-like ileitis. J Immunol. 2012;189:1510–1520. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei Y, Wang D, Topczewski F, Pagliassotti MJ. Saturated fatty acids induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis independently of ceramide in liver cells. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2006;291:E275–281. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00644.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei Y, Wang D, Pagliassotti MJ. Saturated fatty acid-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis are augmented by trans-10, cis-12-conjugated linoleic acid in liver cells. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2007;303:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho H, et al. Signaling dynamics of palmitate-induced ER stress responses mediated by ATF4 in HepG2 cells. BMC systems biology. 2013;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marwarha G, Claycombe K, Schommer J, Collins D, Ghribi O. Palmitate-induced Endoplasmic Reticulum stress and subsequent C/EBPalpha Homologous Protein activation attenuates leptin and Insulin-like growth factor 1 expression in the brain. Cellular signalling. 2016;28:1789–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patterson SI, Skene JH. Inhibition of dynamic protein palmitoylation in intact cells with tunicamycin. Methods in enzymology. 1995;250:284–300. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)50079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee AH, Scapa EF, Cohen DE, Glimcher LH. Regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the transcription factor XBP1. Science. 2008;320:1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1158042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, et al. XBP1 promotes triple-negative breast cancer by controlling the HIF1alpha pathway. Nature. 2014;508:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinon F, Chen X, Lee AH, Glimcher LH. TLR activation of the transcription factor XBP1 regulates innate immune responses in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:411–418. doi: 10.1038/ni.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bettigole SE, et al. The transcription factor XBP1 is selectively required for eosinophil differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:829–837. doi: 10.1038/ni.3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osorio F, et al. The unfolded-protein-response sensor IRE-1alpha regulates the function of CD8alpha + dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:248–257. doi: 10.1038/ni.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cubillos-Ruiz JR, et al. ER Stress Sensor XBP1 Controls Anti-tumor Immunity by Disrupting Dendritic Cell Homeostasis. Cell. 2015;161:1527–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao SS, Kaufman RJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in cell fate decision and human disease. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2014;21:396–413. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drogat B, et al. IRE1 signaling is essential for ischemia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor-A expression and contributes to angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. Cancer research. 2007;67:6700–6707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiu Q, et al. Toll-like receptor-mediated IRE1alpha activation as a therapeutic target for inflammatory arthritis. The EMBO journal. 2013;32:2477–2490. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoo SA, et al. A novel pathogenic role of the ER chaperone GRP78/BiP in rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 2012;209:871–886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watarai H, Nakagawa R, Omori-Miyake M, Dashtsoodol N, Taniguchi M. Methods for detection, isolation and culture of mouse and human invariant NKT cells. Nature protocols. 2008;3:70–78. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maeda M, Lohwasser S, Yamamura T, Takei F. Regulation of NKT cells by Ly49: analysis of primary NKT cells and generation of NKT cell line. J Immunol. 2001;167:4180–4186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayer CM, Belsham DD. Palmitate attenuates insulin signaling and induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in hypothalamic neurons: rescue of resistance and apoptosis through adenosine 5′ monophosphate-activated protein kinase activation. Endocrinology. 2010;151:576–585. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.