The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is thought to link expected rewards and action planning, but evidence for this idea remains sparse. We show that, across contexts, both excitatory and inhibitory cue-evoked activity in the NAc jointly encode reward prediction and probability of behavioral responding to the cue, as well as spatial and locomotor properties of the response. Interestingly, although spatial information in the NAc is updated quickly, fine-grained updating of reward value occurs over a longer timescale.

Keywords: nucleus accumbens, electrophysiology, reward, motivation, locomotion

Abstract

The nucleus accumbens (NAc) has often been described as a “limbic-motor interface,” implying that the NAc integrates the value of expected rewards with the motor planning required to obtain them. However, there is little direct evidence that the signaling of individual NAc neurons combines information about predicted reward and behavioral response. We report that cue-evoked neural responses in the NAc form a likely physiological substrate for its limbic-motor integration function. Across task contexts, individual NAc neurons in behaving rats robustly encode the reward-predictive qualities of a cue, as well as the probability of behavioral response to the cue, as coexisting components of the neural signal. In addition, cue-evoked activity encodes spatial and locomotor aspects of the behavioral response, including proximity to a reward-associated target and the latency and speed of approach to the target. Notably, there are important limits to the ability of NAc neurons to integrate motivational information into behavior: in particular, updating of predicted reward value appears to occur on a relatively long timescale, since NAc neurons fail to discriminate between cues with reward associations that change frequently. Overall, these findings suggest that NAc cue-evoked signals, including inhibition of firing (as noted here for the first time), provide a mechanism for linking reward prediction and other motivationally relevant factors, such as spatial proximity, to the probability and vigor of a reward-seeking behavioral response.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is thought to link expected rewards and action planning, but evidence for this idea remains sparse. We show that, across contexts, both excitatory and inhibitory cue-evoked activity in the NAc jointly encode reward prediction and probability of behavioral responding to the cue, as well as spatial and locomotor properties of the response. Interestingly, although spatial information in the NAc is updated quickly, fine-grained updating of reward value occurs over a longer timescale.

the nucleus accumbens (NAc) is thought to connect the neural representation of reward-predictive stimuli with appropriate motor responses (Mogenson et al. 1980). Under this framework, information about the value of predicted rewards is encoded by structures projecting to the NAc, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and ventral tegmental area (VTA), and integrated by NAc neurons (Freund et al. 1984; McGinty and Grace 2008; O’Donnell and Grace 1995), which influence motor behavior via downstream structures (Deniau et al. 1994; Nicola 2007). Despite the popularity of the “limbic-motor interface” hypothesis (Berridge 2007; Nicola 2016; Niv et al. 2007; Salamone and Correa 2012), it remains unclear whether, as predicted by this hypothesis, individual NAc neurons simultaneously encode information about both the reward predicted by stimuli and the actions to be taken to obtain the reward.

We have recently posited that disruption of the NAc specifically impairs taxic (“flexible”) approach, which is target-directed movement requiring the computation of a novel action sequence (Nicola 2010, 2016). Taxic approach contrasts with praxic approach, which is movement for which the brain already represents a motor plan (O’Keefe and Nadel 1978; Petrosini et al. 1996; Whishaw et al. 1987; Whishaw and Tomie 1987). Both taxic and praxic approach can be elicited by stimuli that prompt movement toward a target associated with a reward. If stimuli are presented unpredictably, taxic approach is typically required; however, if stimuli are presented contingent on the subject’s action, praxic approach is elicited, particularly if the stimulus-action associations are well learned.

Dopamine receptor antagonism in the NAc impairs taxic, but not praxic, approach via increased latency to initiate movement (Nicola 2010). About half of NAc neurons are excited by cues that elicit taxic approach (whereas excitations preceding praxic approach are fewer and smaller), and these excitations precede movement onset and predict latency and speed (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014). Thus NAc excitations could link reward prediction information from upstream limbic structures with taxic approach. Consistent with this idea, cue-evoked excitations are reduced by disruption of input from the basolateral amygdala (Ambroggi et al. 2008), prefrontal cortex (Ishikawa et al. 2008), or VTA (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; Yun et al. 2004). Moreover, excitations are larger in response to cues that predict sucrose reward than to cues that do not (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Nicola et al. 2004a), suggesting that NAc excitations are modulated by the reward prediction encoding of its afferents, and, in turn, set the probability of taxic approach.

This hypothesis implies that NAc neurons that encode reward prediction will also encode the probability of the behavioral response. However, testing this hypothesis is challenging because motivated animals almost always respond to cues that predict reward and rarely respond to cues that do not. In this study, we overcame this difficulty by compiling a large data set of recordings from NAc neurons while rats performed a discriminative stimulus (DS) task (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013), allowing us to robustly test for joint encoding of reward prediction and behavioral response probability. The large data set also allowed us to characterize cue-inhibited neurons, which are fewer and have a limited dynamic range, and to test whether inhibitions predict approach latency, speed, and/or proximity to the target, variables that are strongly encoded by cue-evoked excitations (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014).

Finally, in a decision-making (DM) task based on reward magnitude, we found, surprisingly, that NAc cue-evoked excitations did not exhibit greater excitation, overall, when animals chose larger rewards (Morrison and Nicola 2014). This observation complicates the hypothesis that NAc neurons encode a reward prediction signal that sets behavioral response probability. By comparing NAc neural responses on the DS and DM tasks, we found that both cue-excited and cue-inhibited neurons jointly encode multiple aspects of a cue, including reward prediction, target proximity, and locomotor features of the response, but, in an interesting limitation, they do not discriminate on the basis of recent changes in the reward magnitude predicted by a cue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Subjects

Subjects were 30 male Long-Evans rats obtained from Charles River Laboratories, weighing 275–300 g on arrival. They were singly housed and placed on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle; all experiments took place during the light phase. Rats were allowed to acclimate to the housing colony for at least 3 days and were then habituated to handling over 2–3 sessions. Water was provided ad libitum, and food was provided ad libitum until after habituation, when animals were placed on a restricted diet of 13–15 g of chow (BioServ F-137 dustless pellets) per day. Subjects were also given food ad libitum for 7 days after surgery. If necessary, extra food was provided to maintain a minimum of 90% prerestriction body weight.

Behavioral Apparatus and Tasks

All behavioral training and experiments took place in custom-built Plexiglas chambers measuring 40 × 40 cm (height = 60 cm). These were enclosed in metal cabinets lined with foam for soundproofing, and constant white noise was provided for additional masking of external noise. Cabinets were outfitted with a recessed receptacle for liquid reward delivery, two retractable levers (MED Associates), a speaker for delivery of auditory stimuli, and a video camera (Plexon) for motion tracking. The behavioral tasks were controlled by MED-PC software (MED Associates), and events were captured at 1-ms resolution and recorded concurrently with neural and video data using Plexon hardware and software.

DS task.

Details of task and training have been provided previously (Ambroggi et al. 2008, 2011; du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Nicola et al. 2004a, 2004b). Briefly, during the DS task, two cues, a reward-predictive discriminative stimulus (DS) and a neutral stimulus (NS), were presented at random intervals drawn from a truncated exponential distribution with mean 30 s. The cues were either pure tones of 5 and 12 kHz or an intermittent tone at 6 kHz and a “siren” that cycled from 4 to 8 kHz; the identity of the cues was counterbalanced among subjects. A lever response on the active lever during the DS terminated the cue, which otherwise was presented for 10 s; the NS was always presented for 10 s. Presses on the inactive lever, or on the active lever at times other than DS presentation, had no consequence. The side (left or right) of the active and inactive levers was counterbalanced among subjects. Following an active lever press during the DS, head entry into the reward receptacle resulted in delivery of a drop (~30 µl) of 10% sucrose solution.

DM task.

Details of task and training have been provided previously (Morrison and Nicola 2014). Briefly, during reward-size blocks, the two levers (left or right) were associated with two different reward magnitudes: large or small (~75 or ~45 µl of 10% sucrose solution, respectively). During effort blocks, which were not analyzed in the current study, the two levers were both associated with large reward but had two different effort requirements: 1 press or 16 presses. Each block of trials consisted of 20 forced-choice trials, in which only one lever was available, and 40 free-choice trials, in which both levers were available and rats chose between them. During each session, two reward-size blocks, one with each set of contingencies, were presented back to back, and two effort blocks, one with each set of contingencies, were presented back to back. The starting block type and lever assignments were varied among sessions.

Trials began with the presentation of an auditory cue (intermittent tone of 5,350 kHz), the extension of one or both levers, and the illumination of a cue light over the extended lever(s). The intertrial interval was drawn from a truncated exponential distribution with mean 10 s. Cues were presented for a maximum of 15 s. After the required number of presses was completed on any lever, head entry into the receptacle resulted in reward delivery.

Electrode Arrays and Surgery

Following completion of training, rats were implanted bilaterally with custom-built drivable microelectrode arrays comprising 8 Teflon-insulated tungsten wires (A-M Systems) of impedance 90–120 MΩ; some of the arrays also included a central cannula for drug infusion (du Hoffmann et al. 2011; du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014). The arrays were targeted at the dorsal border of the NAc core (coordinates in mm relative to bregma: anteroposterior +1.4, mediolateral ±1.5, dorsoventral 6–6.5). Surgeries were completed using standard aseptic procedures. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% in oxygen for induction, 1–2% for maintenance) and treated with an antibiotic (Baytril; 10 mg/kg) and an analgesic (ketoprofen; 10 mg/kg).

Histology

The anatomic locations of cells comprising the current data set have been reported previously (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014). After the completion of experiments, rats were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) and direct current (15–50 µA) was passed through each of the electrodes. Rats were then transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 4% formalin or 8% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed, stored in the fixative agent, and then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for at least 3 days before being sectioned with a cryostat (50-µm slices). Sections were mounted on glass slides and stained using cresyl violet. Final locations of electrode tips were determined by identifying electrolytic lesions, and the positions of recorded cells were reconstructed on the basis of those locations combined with experimental notes.

Neural Data Acquisition

After at least 1 week of recovery from surgery, collection of neural data commenced using Plexon hardware and software. Signals were sampled at 40 kHz, amplified 2,000–20,000 times, and bandpass filtered at 250 and 8,800 Hz. Spikes were manually sorted in Offline Sorter (Plexon) using principal component analysis. Only putative units with peak amplitude >75 µV, a signal-to-noise ratio exceeding 2:1, and fewer than 0.1% of interspike intervals <2 ms were analyzed. Using NeuroExplorer software (Nex Technologies), we verified isolation of single units by inspecting autocorrelograms for each unit and cross-correlograms for units recorded on the same electrode. After data were collected at a specific dorsoventral position, electrodes were lowered as a group (typically in increments of 150 µm) to obtain a new set of units.

Video Recording and Analysis of Locomotion

In most sessions, concurrent with neural recording, the rat’s head position and orientation were tracked using an overhead video camera and motion tracking software (Plexon Cineplex V2.0 or V3.0; 30 frames/s, 1.5-mm resolution). The software automatically tracked the location of two LEDs (red and green) mounted on the recording headstage.

Preprocessing of video data, including correction for distortion and skew, has been described in detail previously (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014), as has the calculation of motion onset latencies using individualized threshold values of a “locomotor index,” which is a spatially and temporally smoothed representation of speed (Drai et al. 2000; McGinty et al. 2013). In the current study, motion onset latencies were derived exclusively from trials in which the rat was motionless at cue onset, as determined using the locomotor index. Mean speed and proximity to a rewarded lever, on the other hand, were derived from all trials, even if the rat was moving at cue onset.

For analyses involving proximity/distance, we operationally defined being “near” to a lever as a head position within 12.5 cm of the lever. For the DS task, we considered only the active lever when determining proximity; for the DM task, the subject was considered “near” if proximal to either lever even if the other lever was subsequently pressed.

Analysis of Neural Data

All analyses were performed using custom-written programs in MATLAB (MathWorks). To identify cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions, we first defined a Poisson distribution approximating the baseline firing rate during the 1 s preceding cue onset. Cue-excited neurons were identified by the presence of three or more consecutive 10-ms bins in the 500 ms following cue onset in which firing rate exceeded the 99.9% confidence interval of the baseline Poisson distribution. Similarly, cue-inhibited neurons were identified by the presence of three or more consecutive bins in which firing rate was less than the lower 99.9% confidence interval. The duration of each inhibition was determined by identifying, if present, the first three consecutive bins in which firing rate returned to greater than or equal to the baseline firing rate or, alternatively, the firing rate in the 1 s preceding the onset of the inhibition, whichever was smaller. If no “inhibition off time” was identified within the 500 ms following cue onset, then the duration of the inhibition was set at 500 ms for the purpose of subsequent analyses.

We also evaluated whether the cue response was primarily excitatory or inhibitory by examining the mean Z score, calculated in 10-ms bins relative to a 1-s precue baseline, in the 200 or 400 ms following cue onset. Any putative cue-excited neurons with a negative mean Z score in both of these time windows was excluded from analysis. Likewise, any putative cue-inhibited neurons with a positive mean Z score in both of these time windows was excluded from analysis.

Peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) for individual neurons were calculated using 10-ms bins and are shown smoothed with the use of a 5-bin moving average. Population PSTHs were also calculated using 10-ms bins and normalized as a Z score relative to a 1-s precue baseline before being averaged across neurons. The average activity was then smoothed for display using a 5-bin moving average. Population activity was compared by using firing rates from the most relevant of three windows, as specified in the text: 200 ms following cue onset, 500 ms following cue onset, or 100–300 ms following cue onset. P values were Bonferroni corrected where appropriate.

Except where otherwise noted, analyses of individual neuronal responses [e.g., receiver operating characteristic (ROC)-based indexes] were performed by using firing rates from the 200 ms following cue onset for cue-evoked excitations, as we have done previously (Morrison and Nicola 2014), and individualized custom time windows for cue-evoked inhibitions. Custom windows were defined on a per-cell basis as the time between “inhibition on” and “inhibition off,” as determined by applying the same algorithm used for identification of cue-inhibited cells. Inhibition on times ranged from 10 to 300 ms (median 90 ms); the earliest inhibition off time was 100 ms, although the median was much greater (460 ms). Custom windows were truncated at 500 ms following cue onset; therefore, the length of the analysis window for inhibitions ranged from 70 to 470 ms. Inhibitory responses were transformed as the absolute value of the percent deviation from baseline firing rate, yielding values ranging from 0 (no change from baseline) to 100 (complete absence of firing). To facilitate direct comparison between excitations and inhibitions, excitatory responses were subject to an identical transformation before the same set of analyses.

In several instances, we used ROC analysis to generate an “index” comparing two distributions. These indexes are derived from the area under the ROC curve, with a value of 0.5 indicating distributions that were indistinguishable. We generated P values for individual indexes by randomly reshuffling the data 1,000 times (permutation test). Using this method, we generated a “reward prediction index” (for the DS task) and a “reward magnitude index” (for the DM task) comparing the distributions of neural responses to a rewarded vs. unrewarded cue or a large-reward-predicting or small-reward-predicting cue, respectively. Here and elsewhere, analyses of forced-choice trials from the DM task excluded the first trial of each type (large reward and small reward) from each block. Values of the reward prediction index or reward magnitude index >0.5 indicate a higher firing rate in response to a reward-predictive or large-reward-predictive cue. We also generated a “behavioral response index” comparing neural activity on trials in which the subject did or did not initiate a lever press in response to the cue. Values >0.5 indicate a higher firing rate on trials in which a behavioral response was made. Finally, we generated a “proximity index” comparing neural activity on trials in which the subject was “near” or “far” from a rewarded lever at cue onset. Values >0.5 indicate a higher firing rate on trials in which the subject was near the lever(s).

We used two variants of a generalized linear model (GLM) to evaluate the contribution to variance in firing rate of several factors. First, we applied a “locomotor/spatial” GLM that incorporated factors of latency to motion onset, mean speed, and distance from the active lever:

| (1) |

where xlat is latency to motion onset, xsp is average speed between cue onset and lever press (or, if no lever press is made, within 5 s after cue onset), xdist is lever distance, β0, βlat, βsp, and βdist are the regression coefficients resulting from the model fit, ε is the residual error, and Y is the dependent variable (i.e., firing rate). This form of GLM assumes that the dependent variable follows a Poisson distribution.

Second, we applied a “reward/response” GLM that also incorporated distance from the active lever:

| (2) |

where xrew is a dummy variable representing the reward-predictive quality of the cue (1 for DS, 0 for NS), xDSresp and xNSresp are dummy variables representing whether a behavioral response took place following a DS cue or NS cue, respectively (1 for behavioral response; −1 for nonresponse; 0 if the relevant cue was not presented), and β0, βrew, βDSresp, βNSresp, and βdist are the regression coefficients resulting from the model fit. All other variables are the same as in Eq. 1. Results were largely similar when obtained with the use of a model that excluded distance.

In the sliding regression analysis, this GLM was applied to firing rate from 200-ms bins iteratively “slid” across the trial in 20-ms steps. For display, time points were placed at the beginning of the bin.

To facilitate comparisons between regression coefficients, they were scaled and converted to an estimated change in firing rate resulting from an interdecile shift of the regressor (for continuous variables) or a shift of the regressor from one state to another (for binary variables):

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where βA is the regression estimate for the continuous variable A and IDRA is the interdecile range of that regressor (i.e., the difference between the 10th and 90th percentile); βB is the regression estimate for the binary variable B (as applied to trial type, which was represented by 0 or 1); and βC is the regression estimate for the binary variable C (as applied to behavioral response, which was represented by −1, 0, or 1).

Finally, we used a logistic regression to model the contributions of two factors, trial type and firing rate, to the probability of a behavioral response:

| (6) |

where xrew is a dummy variable representing the reward-predictive quality of the cue (1 for DS, 0 for NS), xfr is firing rate during the analysis window (500 ms following cue onset for excitations, custom for inhibitions), β0, βrew, and βfr are the regression coefficients resulting from the model fit, ε is the residual error, and Y is the dependent variable (i.e., categorical behavioral response/nonresponse).

To ensure the stability of our model estimates, for each regression model, we checked for correlations among predictors by calculating the average variability inflation index (VIF) for each factor. A VIF >10 is generally taken to indicate excessive multicollinearity. The largest average VIF among continuous variables was 1.64, for mean speed in Eq. 1; the largest average VIF among categorical variables was 6.73, for reward prediction in Eq. 2.

RESULTS

Tasks and Behavior

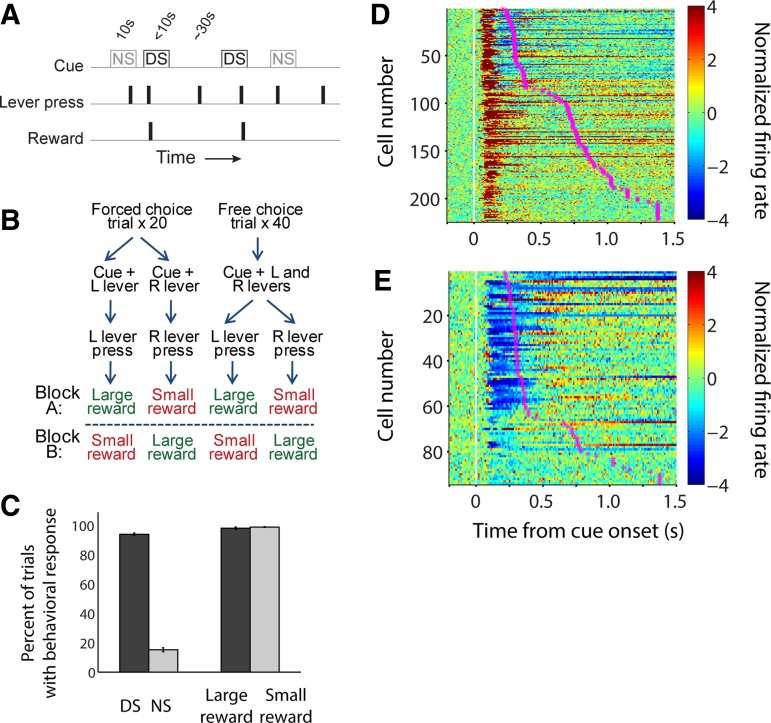

To examine the coding properties of cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions, we recorded from individual neurons in the NAc during a discriminative stimulus (DS) task (Fig. 1A) or a decision-making (DM) task incorporating reward size- and effort-based choices (Fig. 1B). Initial analyses of the data sets used in the current study, as well as full behavioral task and training details, were reported previously (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014). In both the DS and DM tasks, freely moving rats were trained to press a lever on presentation of an auditory cue to obtain a liquid sucrose reward. Cues were presented after a variable intertrial interval (ITI) averaging 30 s (DS task) or 10 s (DM task), ensuring that rats could not predict the time of the next cue. A video tracking system and two head-mounted LEDs were used to monitor rats’ position within the chamber.

Fig. 1.

Distinct subpopulations of NAc neurons exhibit cue-evoked excitations and cue-evoked inhibitions that precede behavioral responses. Individual neurons in the NAc were recorded during a discriminative stimulus (DS) task (A) or a decision-making (DM) task (B). The DM task also included 2 blocks per session in which reward was held constant and effort requirement was varied (not shown). C: average behavioral response rate in the DS task (left) and DM task (right). D and E: average normalized firing rate, aligned on cue onset, among all neurons exhibiting cue-evoked excitatory (D) or inhibitory responses (E). Magenta stars indicate median motion onset time (i.e., start of approach toward the lever) within the session in which the cell was recorded. The large majority of cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions begin (and in many cases end) before most motion onset times.

In the DS task, cues consisted of two distinct tones, presented in random order, one of which (the DS) indicated that the rat could press one of the two available levers (the “active” lever) and then enter the reward receptacle to obtain sucrose. A lever press response terminated the cue; cues were terminated after 10 s if the animal did not respond. The other tone was a nondiscriminative stimulus (NS). Lever presses during the NS, or at any time when the DS was not on, had no programmed consequence. Presses on the other, “inactive” lever had no programmed consequence at any time. As reported previously (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013), rats responded to most DSs by pressing the active lever and did not respond to the majority of NSs (Fig. 1C).

In the DM task, a single auditory cue coincided with the availability of one lever (forced-choice trials) or two levers (free-choice trials), and pressing either lever resulted in reward delivery when the rat subsequently entered the receptacle. One lever was associated with delivery of a large reward and the other with a small reward, and the lever-side reward contingencies were reversed between blocks. Each block consisted of 20 forced-choice trials and 40 free-choice trials, and the order of blocks was varied among sessions.

On forced-choice trials during the DM task, rats responded by pressing the available lever nearly 100% of the time (Fig. 1C). As reported previously (Morrison and Nicola 2014), on free-choice trials during reward-size blocks, subjects mostly chose the lever associated with large reward (69%), indicating that rats learned and based their choices on the reward size associated with each lever. In this report, to facilitate direct comparisons between neuronal responses on the DS and DM tasks, analyses of DM task data focus only on the 40 forced-choice trials.

Cue-Evoked Excitations and Inhibitions in the NAc Reliably Encode Reward Prediction but Not Reward Magnitude

We recorded from a total of 607 individual neurons in the NAc: 448 in the DS task (obtained from 21 rats over 100 behavioral sessions) and 159 in the DM task (obtained from 9 rats over 49 behavioral sessions). Specific recording locations were reported previously (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014). The large majority of cells were located in the NAc core, although some may have been located in the shell or border regions; however, no notable differences in firing characteristics were observed in this subset of neurons.

Consistent with many previous reports (Ambroggi et al. 2011; du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014; Nicola et al. 2004a), we found that about half of all recorded neurons exhibited a significant excitatory response (Fig. 1D) following cue onset: 235 cue-excited neurons (52%) were recorded during the DS task, and 92 cue-excited neurons (58%) were recorded during the DM task. New to this report, we observed that a substantial proportion of NAc neurons exhibited a significant inhibitory response (Fig. 1E) to the cue: 64 cue-inhibited neurons (14%) were recorded during the DS task, and 62 cue-inhibited neurons (39%) were recorded during the DM task. (Because video tracking was unavailable in a small subset of sessions, the number of cells shown in some figures is slightly smaller.)

Notably, the onset (and usually the peak/trough) of both cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions occurred before the rat’s motion onset in the great majority of trials (Fig. 1, D and E). The median latency of cue-evoked excitations was 70 ms, and the median latency of cue-evoked inhibitions was slightly but significantly greater at 90 ms (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test); neither latency to excitation nor latency to inhibition differed between the two tasks (P > 0.1, Wilcoxon rank sum test). In contrast, the median motion onset time among trials in which the rat was motionless at cue onset was 680 ms in the DS task, with a lower quartile value of 580 ms, and 313 ms in the DM task, with a lower quartile value of 204 ms. Thus, in either task, cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions are timed such that they could contribute to the initiation, selection, and/or locomotor features of the subsequent behavioral response.

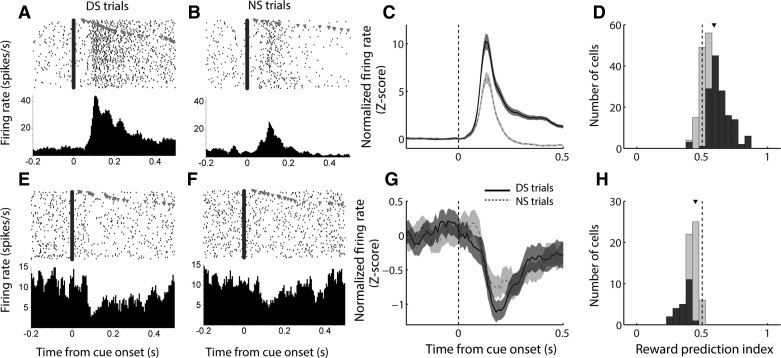

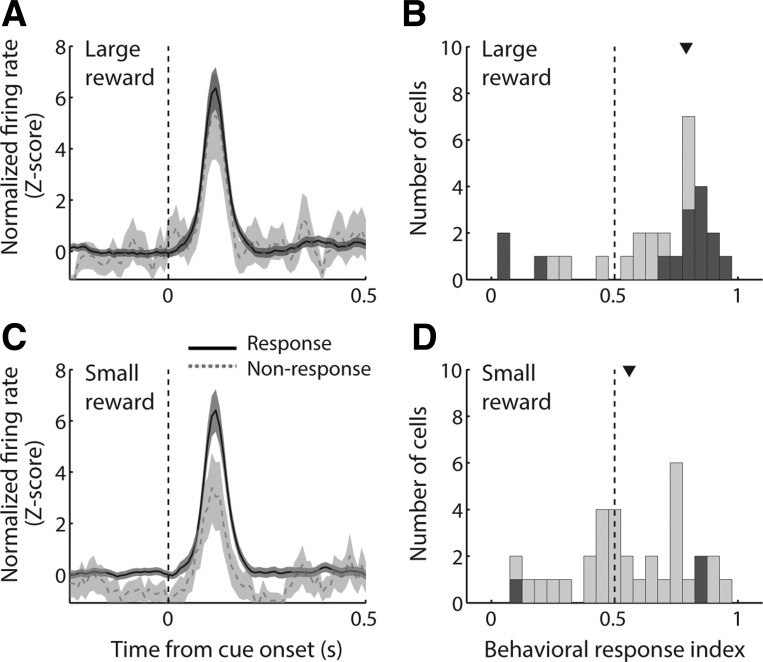

On the basis of their relatively consistent timing, we focused our analyses of cue-evoked excitations on a 200-ms time window following cue onset, as we have done previously (Morrison and Nicola 2014). As we observed in prior studies (Ambroggi et al. 2011; du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Nicola et al. 2004a), in the DS task, cue-excited NAc neurons robustly encoded the motivational significance of the cue (Fig. 2); i.e., they responded much more strongly to the DS, which was predictive of reward, than the NS, which was not. This was true for the population of cue-excited neurons as a whole (Fig. 2C) and also for a large proportion of individual neurons, as measured using a “reward prediction index” based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis (Fig. 2D). The index value for each neuron is the area under the ROC curve derived from firing rate during the analysis window in DS and NS trials; values >0.5 reflect a higher firing rate on DS trials, and values <0.5 represent a higher firing rate on NS trials. The median reward prediction index was significantly greater than 0.5 (P < 0.001, signed-rank test), indicating an overall higher firing rate on DS trials than on NS trials.

Fig. 2.

Cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions encode reward prediction in a DS task. A, B, E, and F: examples of a cell exhibiting cue-evoked excitation (A, B) and a cell exhibiting cue-evoked inhibition (E, F), each of which responds more strongly to the reward-predictive DS cue (A, E) than to the unrewarded NS cue (B, F). C and G: population average cue-evoked response among cells with cue-evoked excitations (C) and inhibitions (G). Black solid line, DS trials; gray dashed line, NS trials; shading, SE. D and H: distribution of reward prediction index among cue-excited cells (D) and cue-inhibited cells (H). Index >0.5 indicates higher firing rate on DS trials; index <0.5 indicates higher firing rate on NS trials. Dark gray bars indicate significant index (P ≤ 0.05, permutation test). Arrowhead indicates median of each distribution.

Because both the onset time and the duration of inhibitions were more variable (Fig. 1E), we used a time window of analysis that was customized for each individual neuron (see materials and methods). We found that, like cue-excited neurons, cue-inhibited neurons responded more strongly to the DS than the NS (Fig. 2, E–H). On average (Fig. 2G) and among a large proportion of individual neurons (Fig. 2H), cells exhibited stronger inhibitions (i.e., had lower firing rates) in response to a cue that was predictive of reward. The median reward prediction index was significantly less than 0.5 (P < 0.001, signed-rank test), indicating an overall lower firing rate on DS trials than on NS trials. Thus both excitatory and inhibitory responses of NAc neurons encoded the reward-predictive properties of cues.

The DM task differed from the DS task in two important ways: 1) both cues (i.e., the auditory cue combined with extension of either the left or right lever) were predictive of reward, although the reward varied in magnitude (large or small), and 2) the lever-reward contingencies were reversed between blocks such that subjects experienced an equal number of large and small rewards paired with each cue during training and testing. Under these circumstances, we found that NAc cue-evoked excitations did not encode the magnitude of the reward associated with the cue (Fig. 3, A–D). The population average response (Fig. 3C) did not differ between forced-choice trials that resulted in large or small reward, and the median reward magnitude index (Fig. 3D; analogous to the reward prediction index in Fig. 2, D and H) was not significantly shifted from 0.5 (P > 0.1, signed-rank test).

Fig. 3.

Cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions exhibit minimal encoding of reward magnitude in a decision-making task. A, B, E, and F: examples of a cell exhibiting cue-evoked excitation (A, B) and a cell exhibiting cue-evoked inhibition (E, F), each of which shows little difference in response to a cue predicting large reward (A, E) or small reward (B, F) during forced-choice trials. C and G: population average cue-evoked response among cells with cue-evoked excitations (C) and inhibitions (G). Black solid line, large-reward forced-choice trials; gray dashed line, small-reward forced-choice trials; shading, SE. Among inhibitions only, there is significantly higher firing (i.e., less inhibition) on small-reward trials in the time period 100–300 ms following cue onset. D and H: distribution of reward magnitude index among cue-excited cells (D) and cue-inhibited cells (H). Index >0.5 indicates higher firing rate on large-reward trials; index <0.5 indicates higher firing rate on small-reward trials. Dark gray bars indicate significant index (P ≤ 0.05, permutation test). Arrowhead indicates median of each distribution.

Cue-evoked inhibitions (Fig. 3, E–H) exhibited nearly identical properties to cue-evoked excitations during the DM task: although the population average response (Fig. 3G) was slightly stronger (i.e., more inhibited) on large-reward trials during the time window from 100 to 300 ms following cue onset (P = 0.052, Wilcoxon rank sum test), the median reward magnitude index (Fig. 3H) was not significantly shifted from 0.5 (P > 0.1, signed-rank test). Thus, during the DM task, neither excitatory nor inhibitory neural responses in the NAc reliably reflected the magnitude of the reward associated with a given cue during that trial block.

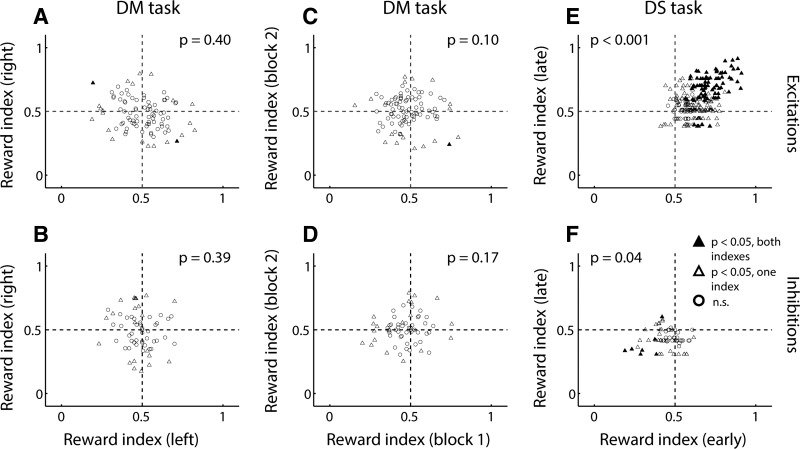

These observations were consistent with our previous finding (Morrison and Nicola 2014) that NAc cue-evoked excitations did not exhibit an overall preference for cues that preceded large or small reward on free-choice trials; they also did not exhibit consistent encoding of reward magnitude on free- vs. forced-choice trials. When we focused exclusively on forced-choice trials, despite the lack of population-wide preference for cues associated with large or small reward (Fig. 3, C and G), a handful of individual neurons did show significant encoding of reward magnitude (Fig. 3, D and H). However, we reasoned that if reward magnitude representations were truly stable, then similar reward magnitude encoding should be observed for a given neuron no matter which lever the animal responds on, and no matter whether the trials occur early or late in the session. Therefore, we compared the reward magnitude index obtained from left lever trials and right lever trials (Fig. 4, A and B) and found a lack of consistent encoding: among both cue-evoked excitations (Fig. 4A) and inhibitions (Fig. 4B), index values were not significantly clustered in any quadrant (McNemar’s test, P > 0.05). Next, we compared the reward magnitude index as measured during the first vs. second block of forced-choice trials (Fig. 4, C and D) and again found no clear relationship (no significant clustering, McNemar’s test, P > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions exhibit little stable encoding of reward information in the DM task, in contrast to the DS task. A and B: reward magnitude index comparing responses to the same lever (left or right) when its extension predicts large vs. small reward. Index for left lever is plotted against index for right lever within the same session for excitations (A) and inhibitions (B). C and D: reward magnitude index comparing responses to the large-reward-predictive and small-reward-predictive lever during the same block of trials. Index for chronological block 1 is plotted against index for block 2 within the same session for excitations (C) and inhibitions (D). E and F: reward prediction index comparing responses to the DS cue vs. the NS cue. Index for first half of session (early) is plotted against index for second half of session (late) for excitations (E) and inhibitions (F). In A–F: filled triangles, both indexes significant (P ≤ 0.05, permutation test); open triangles, one index significant; open circles, neither index significant. P values represent results of a McNemar’s test for correlated proportions.

By way of comparison, we performed an analogous analysis on cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions recorded during the DS task: we compared the reward prediction index measured during the first half and second half of trials completed in a given session (Fig. 4, E and F) and, as expected, found significant clustering of index values in the first quadrant for cue-evoked excitations (Fig. 4E; McNemar’s test, P < 0.001) and in the third quadrant for cue-evoked inhibitions (Fig. 4F; P = 0.04). This indicates that a neuron’s preferential firing in response to the DS (or NS) usually remains consistent throughout the session. Thus the NAc stably represents the reward-predictive properties of cues during the DS task, but during the DM task, the specific reward magnitude predicted by a cue is not represented in a stable manner by cue-evoked excitations or inhibitions in the NAc.

Across Task Contexts, NAc Cue-Evoked Excitations and Inhibitions Encode Variables Related to the Vigor of the Subsequent Behavioral Response

We have previously shown that cue-evoked excitatory responses in the NAc encode various locomotor features of the subsequent approach to a lever, as well as proximity to a reward-associated lever at cue onset (McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014). Because they occur before motion onset (see Fig. 1, D and E), these signals could play a role in the invigoration of approach toward rewarding objects in the environment. We next sought to establish whether cue-evoked inhibitions, as well as excitations, could participate in the invigoration of approach, and to determine how the encoding of locomotor and spatial factors interacts with the representation of reward across task contexts. To facilitate a direct comparison with the results of the DS task, we again focused our DM task analyses on forced-choice trials.

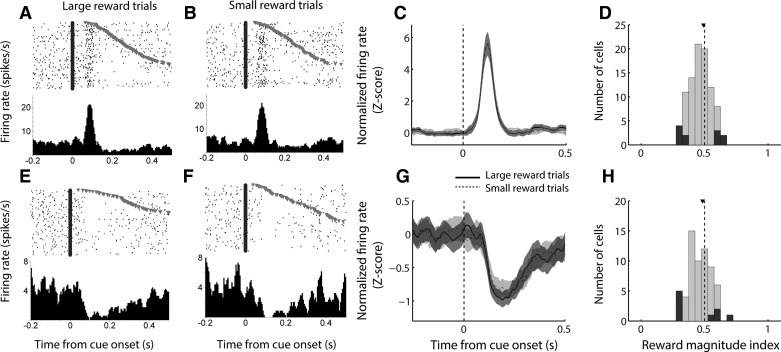

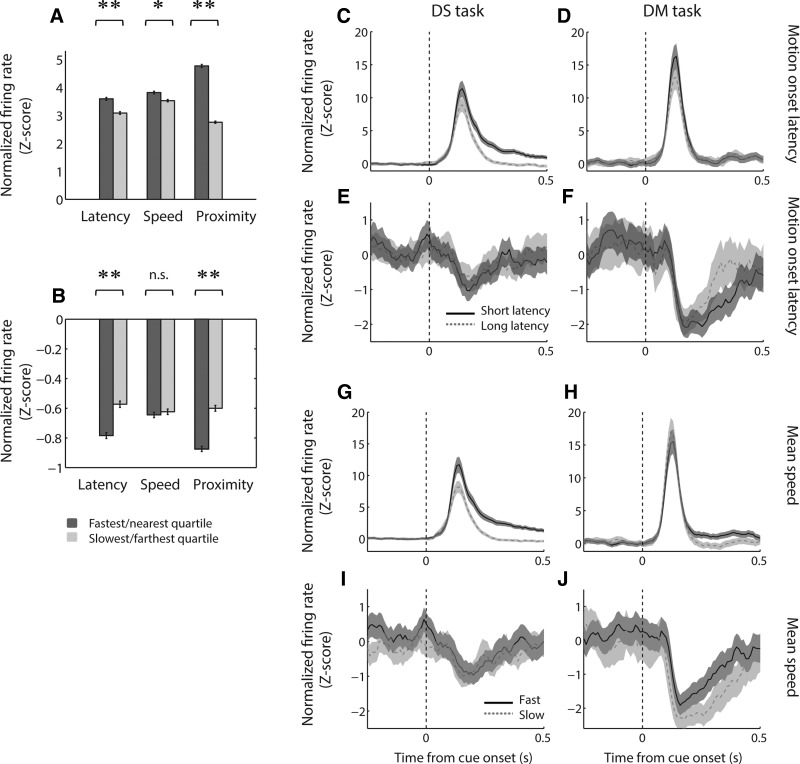

Among the current large data set, we used a quartile-based analysis (Fig. 5A) to confirm that cue-evoked excitations were significantly stronger when the subject had a short, rather than long, latency to begin moving (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test); attained a fast, rather than slow, average speed (P < 0.05); and was near, rather than far, from a rewarded lever at cue onset (P < 0.001). Similarly, cue-evoked inhibitions were of greater magnitude on short-latency trials and on trials in which the subject was near a rewarded lever (both comparisons, P < 0.001; Fig. 5B), although no significant difference was found for mean speed (P > 0.1). These differences were replicated in the population average activity from each task (Fig. 5, C–J), although excitations recorded during the DM task were more weakly modulated by locomotor factors, reflecting the smaller range of behavioral variability when all trials were rewarded. Note that the enhanced inhibition on “slow” trials observed in the DM task likely reflects the strong effect of proximity during this task (see Fig. 6D) because subjects tend to attain greater speeds on “far” trials (McGinty et al. 2013). Overall, these findings suggest that cue-evoked inhibitions, like excitations, could contribute to the vigor of approach behavior elicited by the cue.

Fig. 5.

Cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions encode locomotor features of the behavioral response. A and B: average normalized firing rate during trials with, from left, short or long motion onset latency (bottom vs. top quartile), fast or slow mean motion speed (top vs. bottom quartile), and near or far proximity to a reward-associated lever. Firing rate is shown for cue-evoked excitations in the 200 ms following cue onset (A) and for cue-evoked inhibitions in cell-specific custom response windows (B). *P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test; **P < 0.001. Error bars, SE. C–J: population average cue-evoked response among cue-excited cells (C, D, G, H) and cue-inhibited cells (E, F, I, J) during the DS task (C, E, G, I) and the DM task (D, F, H, J). In C–F: black solid line, trials with motion onset latency in the bottom quartile (faster); gray dashed line, trials with motion onset latency in the top quartile (slower). In G–J: black solid line, trials with mean movement speed in the top quartile (faster); gray dashed line, trials with mean movement speed in the bottom quartile (slower); shading, SE.

Fig. 6.

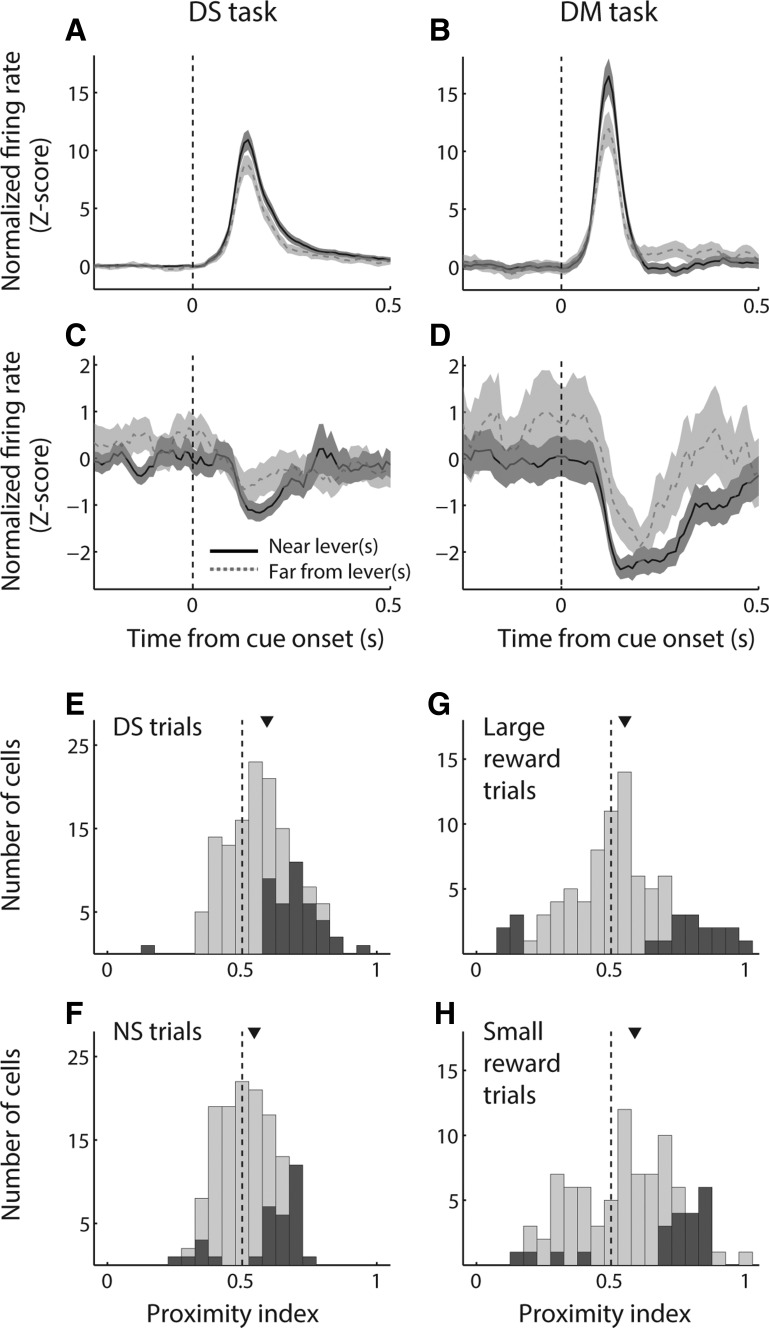

Cue-evoked neural responses encode proximity to a reward-associated lever in concert with reward prediction. A–D: population average cue-evoked response among cue-excited cells (A, B) and cue-inhibited cells (C, D) during the DS task (A, C) and the DM task (B, D). Black solid line, trials in which the subject is located near a reward-associated lever at cue onset; gray dashed line, trials in which the subject is far from a reward-associated lever; shading, SE. E–H: distribution of a proximity index among cue-excited cells in the DS task (E, F) and the DM task (G, H). Proximity index >0.5 indicates higher firing rate when the subject is near a reward-associated lever at cue onset; index <0.5 indicates higher firing rate when the subject is far from a reward-associated lever at cue onset. Dark gray bars indicate significant index (P ≤ 0.05, permutation test). The proximity index is derived from firing rate in the 200 ms following cue onset. Arrowhead indicates median of each distribution. The median of each distribution is significantly shifted from zero (P < 0.05, signed-rank test). The median index is significantly higher for DS trials than for NS trials (P = 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test), whereas the median indexes for large-reward trials and small-reward trials are not different (P = 0.24).

We gave special consideration to NAc encoding of proximity, which had a large effect on firing rate in both cue-excited and cue-inhibited cells (Fig. 5, A and B) and which we have previously shown to be strongly and consistently represented across contexts within the DM task (Morrison and Nicola 2014). As we have done previously (Morrison and Nicola 2014), we operationally defined being “near” a rewarded lever as a head position within 12.5 cm of the lever; all other trials were categorized as “far.” Within both the DS and the DM task, we observed robust differences in the population average activity on near and far trials, which were present among both cue-evoked excitations (Fig. 6, A and B) and inhibitions (Fig. 6, C and D). Among excitations, activity was significantly higher on near trials than far trials in the 500 ms following cue onset (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test); among inhibitions, activity was significantly lower in the 100–300 ms following cue onset (P < 0.05). Thus, across task contexts, both cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions could participate in promoting approach to nearby reward-associated stimuli.

We next asked whether cue-evoked excitations are modulated by proximity in concert with reward. To do so, we calculated a “lever proximity index” by using ROC analysis to compare cue-evoked excitations on trials in which the rat was near or far from a rewarded lever at cue onset (Fig. 6, E–H). We found that the median lever proximity index was significantly greater than 0.5, indicating stronger firing on near trials than on far trials for both DS trials (P < 0.001, signed-rank test) and NS trials (P = 0.004) in the DS task and for both large-reward forced-choice trials (P = 0.02) and small-reward forced-choice trials (P < 0.001) in the DM task. In addition, we noted that the median lever proximity index was significantly greater for DS trials than for NS trials (P = 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test), implying that proximity is encoded more strongly with respect to a rewarded cue compared with an unrewarded cue. In contrast, the median lever proximity index was not different for large-reward vs. small-reward trials in the DM task (P > 0.1), which is consistent with our previous analyses demonstrating the NAc’s overall lack of discrimination between cues in the DM task based on their associated reward magnitudes.

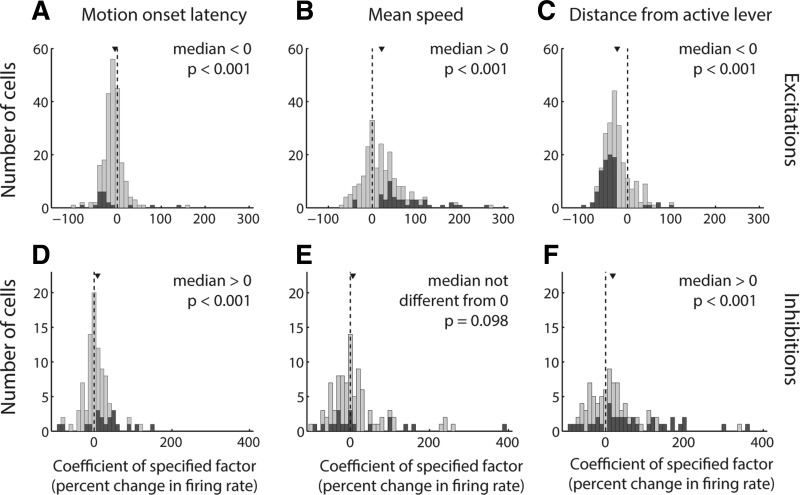

Finally, we sought to establish whether, in different task contexts, NAc cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions encode locomotor and spatial features of the upcoming behavioral response as independent contributors to variance. We chose to apply a GLM (Eq. 1) incorporating three specific variables, latency to motion onset, average speed, and proximity to the motion target at cue onset, because these variables are representative of the three major categories of locomotor/spatial factors (latency, speed, distance) that have been shown to have the greatest impact on the strength of NAc cue-evoked excitations (McGinty et al. 2013). Although some correlation is present among these factors, in this and in subsequent GLM analyses, the degree of multicollinearity was well within generally accepted limits for stability of the model estimates (see materials and methods). For the purposes of this analysis, we combined data from the DS and DM task and found that latency, speed, and proximity are indeed encoded independently among cue-evoked excitations across the data set (Fig. 7, A–C). Consistent with the quartile analysis (Fig. 5, A and B) and population activity profiles (Fig. 5, C–J, and Fig. 6, A–D), the distribution of coefficients for each of these factors was significantly shifted in the negative direction (for latency and distance; P < 0.001, signed-rank test) or the positive direction (for speed; P < 0.001).

Fig. 7.

Locomotor characteristics and proximity are independent contributors to variance among cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions. A–F: distributions of coefficients derived from a GLM with factors of motion onset latency (A, D), mean speed (B, E), and distance from a reward-associated lever (C, F) for all cells from both the DS and DM tasks. Each coefficient is derived from the β value associated with the specified factor and normalized as the expected change in firing rate over an interdecile shift in the variable. The GLM was applied to cue-evoked excitations in the 200 ms following cue onset (A–C) and to cue-evoked inhibitions in custom-response windows (D–F). Dark gray bars indicate coefficients derived from significant β values. Arrowhead indicates median of each distribution. The median of each distribution is significantly shifted from zero (P < 0.001, signed-rank test), with the exception of the mean speed coefficient for inhibitions (E).

Similarly, cue-evoked inhibitions exhibited independent encoding of latency and proximity, with coefficients significantly shifted in the positive direction (P < 0.001, signed-rank test), indicating stronger inhibition (i.e., lower firing rate) for short-latency and near-lever trials. Consistent with the quartile analysis and population activity profile, the median coefficient for speed was not significantly different from zero (P = 0.1). Overall, both cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions in the NAc reflect locomotor and spatial factors of the upcoming behavioral response, suggesting that, across task contexts, bidirectional cue-evoked NAc activity could play an important role in the initiation and invigoration of approach toward cues that are associated with reward.

Encoding of Reward Prediction in NAc is Strongly Linked to the Subsequent Execution of a Behavioral Response

In this and previous studies (McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014), we showed that NAc cue-evoked excitations encode locomotor features of the subsequent behavioral response, including motion onset latency and speed, among others. We also showed that excitations are attenuated during trials in which the subject fails to respond to the cue (McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014). These results suggest the simple hypothesis that encoding of reward prediction drives the behavioral response; i.e., NAc cue-excited neurons fire more robustly to cues predicting greater reward, and this greater firing causes an increased probability of approach toward a reward-associated lever. This hypothesis predicts that the same neurons that encode reward prediction should also encode propensity to respond. However, in our previous studies, behavioral responding was not analyzed in conjunction with the reward-related components of neural activity, leaving open the alternative hypothesis that different populations of NAc cue-excited neurons encode reward prediction and behavioral responding. Therefore, it remains unclear whether and how the representation of expected reward interacts with activity reflecting the subsequent behavioral response.

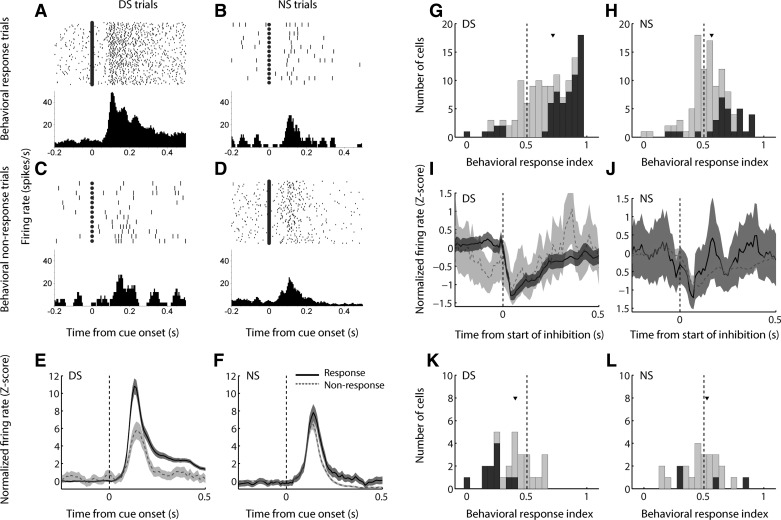

To investigate the relationship between neural activity related to reward prediction and activity related to the subsequent behavioral response, we separately examined cue-evoked excitations on DS and NS trials in which the subject did or did not initiate a behavioral response to the cue (Fig. 8). We found that NAc neurons typically did not encode “pure” reward prediction or behavioral responding; instead, the most common neural response profile was a nonlinear interaction between reward and behavior, as exemplified in Fig. 8, A–D. This cell, which is the same as that shown in Fig. 2, A and B, significantly discriminated between DS and NS trials only when the cue was followed by action; likewise, it only discriminated between behavioral response and nonresponse trials when the cue was predictive of reward (P < 0.001 for DS/response trials vs. all other trial types, ANOVA with Dunn-Sidak post hoc test; all other comparisons, P > 0.1). This response profile was largely reflected by the neuronal population as a whole (Fig. 8, E and F): the difference in population average activity between response and nonresponse trials was much more prominent for the DS (Fig. 8E) than for the NS (Fig. 8F), although both were significantly different over the 500 ms following cue onset (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Fig. 8.

In the DS task, cue-evoked firing jointly encodes reward prediction and the subsequent behavioral response. A–D: an example cell shows markedly enhanced cue-evoked excitation when the DS cue is subsequently followed by a lever press (A) than when the DS cue does not elicit a behavioral response (B) or when the cue is not associated with reward (C, D), regardless of subsequent behavioral response. E and F: population average of cue-evoked excitations following the DS cue (E) or the NS cue (F). Black solid line, trials in which the cue was followed by a behavioral response; gray dashed line, behavioral nonresponse trials; shading, SE. G and H: distribution of behavioral response index for excitations on DS and NS trials, respectively. Index >0.5 indicates higher firing rate on trials with a behavioral response; index <0.5 indicates higher firing rate on nonresponse trials. Dark gray bars indicate significant index (P ≤ 0.05, permutation test). Arrowhead indicates median of each distribution. The medians of both distributions are significantly shifted from 0.5 (P < 0.001, signed-rank test) as well as from each other (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test). I and J: population average of cue-evoked inhibitions following the DS cue (I) or the NS cue (J). Conventions are as in E and F. K and L: distribution of behavioral response index for inhibitions on DS and NS trials, respectively. Conventions are as in G and H.

To examine how the activity of individual neurons reflected subsequent behavior, we quantified the difference between response and nonresponse trials by using a “behavioral response index” calculated using ROC analysis (Fig. 8, G and H). We found that the median response index for both trial types was significantly greater than 0.5 (P < 0.001, signed-rank test), indicating stronger firing to cues that were followed by a behavioral response. However, the median behavioral response index for DS trials was significantly shifted from the median for NS trials (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test), reflecting a strong interaction between neural encoding of reward prediction and behavior.

Among cue-evoked inhibitions, the population response profile on DS trials (Fig. 8I) reflected the presence or absence of a subsequent behavioral response, although to a lesser degree than cue-evoked excitations. This was likely due to the smaller number of cue-inhibited cells, compared with cue-excited cells, in the data set, as well as the inherent “floor” of zero spikes restricting the maximum inhibitory response. Similar to the population of cue-excited cells, the effect of behavioral response/nonresponse was far less apparent in the population response profile on NS trials (Fig. 8J). Consistent with these results, the median behavioral response index among DS trials (Fig. 8K) was significantly less than 0.5 (P = 0.004, signed-rank test), indicating a lower firing rate (i.e., stronger inhibition) on trials in which the subject responded to the cue. The median behavioral response index among NS trials was not shifted from 0.5 (P > 0.1). Moreover, the median behavioral response index for DS trials was significantly smaller than that for NS trials (P = 0.04, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Thus both cue-evoked excitations and inhibitions simultaneously reflect aspects of reward prediction and behavioral response.

In the DM task, unlike the DS task, only a small minority of cues on forced-choice trials (mean = 2.3%) did not elicit approach toward the lever. Even so, the impact of behavioral response or nonresponse on cue-evoked excitations (there were too few trials of each type to analyze inhibitions in this context) was evident: although the difference in population average neural activity was minimal for large-reward trials (Fig. 9A), the median behavioral response index (Fig. 9B) was significantly greater than 0.5 (P = 0.004, signed-rank test), indicating that the majority of individual neurons had stronger firing in response to cues that were followed by action. Moreover, the difference in population average activity was significant in the 500 ms following cue onset for small-reward trials (Fig. 9C; P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test) and when large- and small-reward trials were combined (not shown; P = 0.002). The median behavioral response index on small-reward trials (Fig. 9D) was greater than 0.5 (P = 0.053, signed-rank test), but, intriguingly, the behavioral response index for large-reward trials showed a trend toward being larger than that for small-reward trials (P = 0.086, Wilcoxon rank sum test), hinting at an interaction between neural encoding of reward size and behavior similar to that seen in the DS task (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9.

Behavioral response or nonresponse contributes to cue-evoked excitations in the DM task. A and C: population average of cue-evoked excitations following the large-reward cue (A) or small-reward cue (C). Only forced-choice trials are included. Black solid line, trials in which the cue was followed by a behavioral response; gray dashed line, behavioral nonresponse trials; shading, SE. B and D: distribution of behavioral response index for large-reward and small-reward trials, respectively. Index >0.5 indicates higher firing rate on trials with a behavioral response; index <0.5 indicates higher firing rate on nonresponse trials. Dark gray bars indicate significant index (P ≤ 0.05, permutation test). Arrowhead indicates median of each distribution. The medians of both distributions are significantly shifted from 0.5 (large-reward trials: P = 0.004, signed-rank test; small reward trials: P = 0.05) but are not significantly different from each other (P = 0.09, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

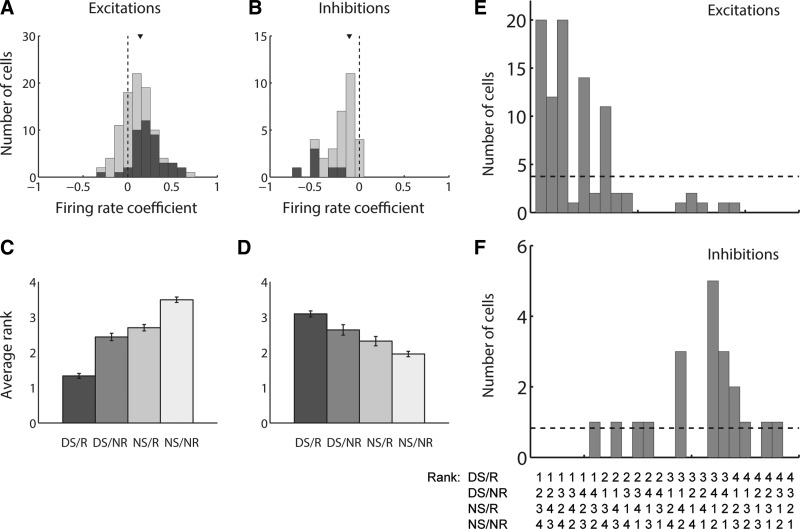

The fact that the same neurons encode information about both reward prediction and the subsequent behavioral response supports the hypothesis that prediction of reward enhances the neural response in a way that promotes approach behavior. However, this does not explain why behavioral response is encoded less strongly on NS/small-reward trials than on DS/large-reward trials (Figs. 8 and 9). One possible explanation is that minor fluctuations in firing on NS trials, whether caused by uncertainty about the reward prediction or unrelated factors, are sometimes sufficient to raise the probability of a behavioral response to appreciable levels. During DS trials, on the other hand, prediction of reward usually drives the neural response sufficiently to ensure a high probability of behavior. If this is the case, then we should see a relationship between firing rate and the probability of a behavioral response that is independent of reward prediction. To test this hypothesis, we modeled behavioral response probability using a logistic regression (Eq. 6) with factors of trial type (DS or NS) and firing rate (Fig. 10, A and B). The coefficient for trial type was always positive (data not shown), consistent with the greater probability of behavioral responding on DS trials. More importantly, the distribution of coefficients associated with firing rate was significantly shifted from zero for both excitations (Fig. 10A; P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test) and inhibitions (Fig. 10B; P < 0.001), showing that increases in firing (for excitations) or decreases in firing (for inhibitions) contribute to behavioral response probability in a manner that is independent from the identity or reward-predictive qualities of the cue.

Fig. 10.

Magnitude of cue-evoked excitation or inhibition contributes to behavioral response probability independently from the reward-predictive quality of the cue. A and B: results of a logistic regression modeling response probability with factors of cue identity (DS or NS) and firing rate for excitations (A) and inhibitions (B). Coefficients for firing rate are shown. Coefficients for cue identity (not shown) were uniformly positive (for excitations) or negative (for inhibitions). Dark gray bars indicate coefficients derived from significant β values. Arrowhead indicates median of each distribution. The median of each distribution is significantly shifted from zero (P < 0.001, signed-rank test). C–F: rank-order analysis in which each of the 4 trial types was assigned rank 1–4 based on firing rate relative to the other trial types (1 representing the highest firing rate and 4 the lowest). The 4 trial types include DS with behavioral response (DS/R), DS with nonresponse (DS/NR), NS with response (NS/R), and NS with nonresponse (NS/NR). C and D: average rank of each of the 4 trial types among excitations (C) and inhibitions (D). E and F: number of cue-excited (E) and cue-inhibited (F) cells recorded, reflecting each of the 24 possible rank orders. Dashed horizontal line represents the number of cells in each category that would be expected by chance.

Another prediction of this hypothesis is that cue-excited and cue-inhibited cells will respond in a predictable manner, on average, to four trial types: DS with a subsequent behavioral response (DS/R), eliciting the greatest neural response; NS with no behavioral response (NS/NR), eliciting the smallest neural response; and DS/nonresponse (DS/NR) and NS/response (NS/R) trials, falling in between. Therefore, for each cue-modulated neuron, we assigned ranks to each of the four trial types based on the corresponding average firing rate elicited by the cue (a rank of 1 indicated the highest firing rate and a rank of 4 the lowest) and calculated the average rank for each trial type (Fig. 10, C and D). We found that both cue-evoked excitations (Fig. 10C) and inhibitions (Fig. 10D) were indeed greatest, on average, during DS/R trials and smallest during NS/NR trials (single trial type compared with all others; P < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Moreover, in both cases, the average ranks for DS/NR trials and NS/R trials fell in between the two extremes and were statistically indistinguishable (P > 0.05). When we plotted the occurrence of each individual rank order (Fig. 10, E and F), we found that the frequency of certain rank orders far exceeded chance, particularly those in which DS/R trials elicited the greatest modulation of firing. Overall, these findings support the notion that NAc neuronal signaling increases the probability of action in a manner that is often, but not exclusively, promoted by prediction of reward.

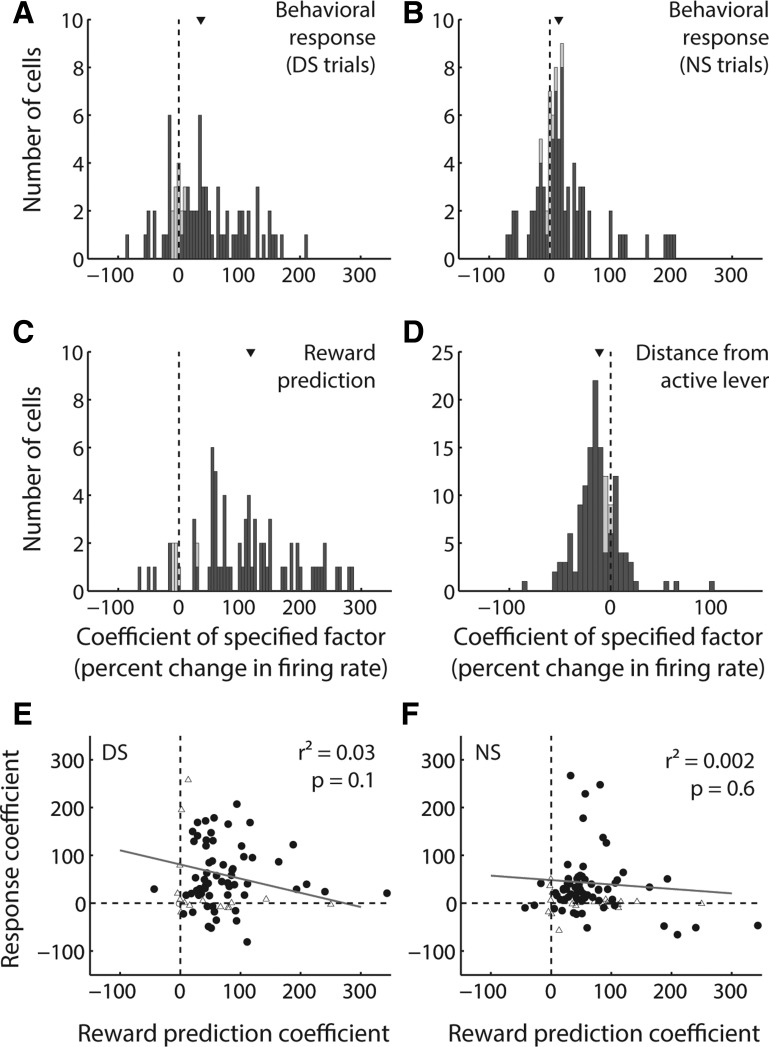

To determine whether reward prediction and action are indeed encoded independently, we used a GLM (Eq. 2) with factors including cue type (DS or NS) and behavioral response (Fig. 11). For this analysis, we focused specifically on activity from cue-excited cells measured during the DS task, which provided an adequate number of sessions containing at least one DS nonresponse trial and one NS response trial. To assess interaction effects, we separately modeled the contributions of behavioral response during DS and NS trials; we also included a factor accounting for proximity to the active lever at cue onset, because we have previously shown that this is a major contributor to NAc cue-evoked excitatory activity (McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014). We normalized the regression estimate for each binary factor by expressing it as the expected change in firing rate resulting from a shift in reward prediction (from unrewarded to rewarded) or a shift in behavior (from nonresponse to response). The regression estimate for proximity was expressed as the expected change in firing rate resulting from an interdecile shift in the regressor (i.e., from small distances to large distances).

Fig. 11.

Among cue-evoked excitations, reward prediction, behavioral response, and proximity to lever are independent contributors to variance. A–D: distribution of coefficients derived from a GLM with factors of behavioral response on DS trials (A), behavioral response on NS trials (B), reward prediction derived from DS or NS cue identity (C), and distance from the active lever (D). Each coefficient is normalized as the expected change in firing rate over an interdecile shift in the variable (for distance) or a switch in the binary variable (for all other factors). Dark gray bars indicate coefficients derived from significant β values. Arrowhead indicates median of each distribution. The median of each distribution is significantly shifted from zero (P < 0.001, signed-rank test). E and F: reward prediction coefficient (as in C) plotted against behavioral response coefficient (as in A and B) for DS trials (E) and NS trials (F). Solid line is regression line. In neither case is the correlation significant (P > 0.05).

We found that all four of these factors, even when considered together, significantly contributed to the variance in cue-evoked activity in most cue-excited neurons (dark gray bars in Fig. 11, A–D). The resulting distributions of coefficients were significantly shifted in the positive direction (median > 0; P < 0.001, signed-rank test) for behavioral response/nonresponse in both cue conditions (Fig. 11, A and B) and for reward prediction (Fig. 11C). Together with previous analyses (Figs. 2 and 8), this result indicates that firing is greater following a reward-associated cue and preceding an action in response to the cue. Moreover, the median behavioral response coefficient for DS trials was significantly larger than that for NS trials (P = 0.02, signed-rank test), confirming that the presence or absence of an action elicited by the cue has a greater impact on NAc neural activity when the cue is predictive of reward. Finally, the behavioral response coefficient did not significantly covary with the reward prediction coefficient for either trial type (Fig. 11, E and F; P > 0.05); thus, although the majority of individual neurons encoded both factors, the degree of encoding of each was independent of the other.

Consistent with our previous findings (McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014), the distribution of coefficients for proximity was significantly shifted in the negative direction (median < 0; P < 0.001, signed-rank test), indicating that NAc cue-evoked firing is stronger when subjects are near to the active lever (i.e., distance is smaller) at cue onset and demonstrating that the representation of proximity is at least partially independent of both reward prediction and subsequent action in response to the cue. When proximity was excluded from the GLM, results for the other coefficients were qualitatively similar (data not shown), consistent with the relatively small magnitude of the median proximity coefficient compared with the magnitudes of the coefficients for behavioral response and reward.

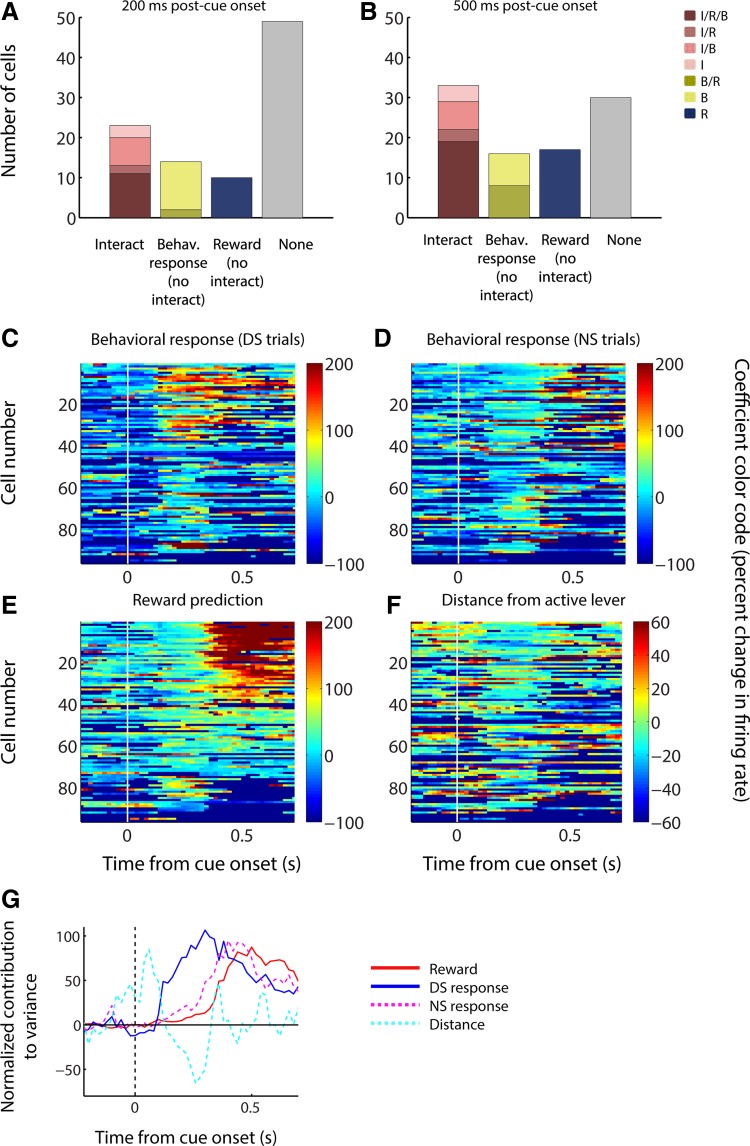

All of the findings thus far suggest that the dominant neural activity profile found in the NAc during the DS task is joint encoding of reward prediction and the likelihood of a behavioral response. To quantify the proportion of cells with this pattern of activity, we next applied an ANOVA with main factors of cue type (DS or NS) and behavioral response, as well as an interaction factor (Fig. 12, A and B). Approximately half of cue-excited neurons (49%) had significant effects (P < 0.05) of one or more factors in the 200 ms following cue onset (Fig. 12A), and an even larger proportion (69%) in the 500 ms following cue onset (Fig. 12B); among these cells, a plurality comprising approximately half showed a significant interaction of reward and behavioral response, with the remainder split between main effects of reward and response. Thus an interaction effect (i.e., a wholly or partially linked representation of reward prediction and behavioral response) is indeed the most common single neural activity profile.

Fig. 12.

Cue-evoked excitations encode subsequent behavioral response earlier than reward prediction in the DS task. A and B: results of an ANOVA, applied to a 200-ms (A) or 500-ms (B) post-cue time window, incorporating reward prediction (based on DS or NS cue identity), behavioral response/nonresponse, and an interaction factor. I, significant interaction effect; R, significant main effect of reward prediction; B, significant main effect of behavioral response/nonresponse. For all effects, α = 0.05. Note the increased prevalence of reward and/or interaction encoding compared with behavioral response encoding over time. C–F: results of a sliding GLM (200-ms bins slid by 20 ms) with factors of behavioral response on DS trials (C), behavioral response on NS trials (D), reward prediction (E), and distance from the active lever (F). Colors indicate the magnitude of the coefficient for the specified factor (normalized as in Fig. 6). Each row represents a single neuron, and cells are shown in the same order in each plot. G: time course of the contribution to variance of reward (red solid line), behavioral response on DS trials (blue solid line), behavioral response on NS trials (magenta dashed line), and distance from the active lever (cyan dashed line). Contribution to variance is normalized as the baseline-subtracted percent maximum for each coefficient independently.

We were interested to note that the relative proportion of neurons with a significant main effect of reward and/or an interaction effect was larger when a longer time window was considered (500 ms instead of 200 ms); in contrast, the relative proportion of neurons with a significant main effect of behavioral response was smaller (Fig. 12, A and B). This finding suggested that, counterintuitively, the neural representation of the behavioral response to a cue might become prominent at an earlier time point in the trial than the representation of the reward predicted by the cue. To test this hypothesis, we applied the same four-factor GLM shown in Fig. 11 to firing rate measured in sliding time windows across the trial (200-ms windows slid by 20-ms steps), yielding a time course for each factor’s contribution to neural activity (Fig. 12, C–G). For ease of comparison, in all cases (Fig. 12, C–F), neurons are sorted by the average contribution of reward prediction to the variance in firing in the 500 ms following cue onset. We found that, during DS trials, the peak contribution of behavioral response indeed occurred earlier in the trial than that of reward prediction. Furthermore, the same neurons that had a strong contribution of behavioral response early in the trial (warm colors in Fig. 12C) were likely to have a strong contribution of reward prediction later in the trial (warm colors in Fig. 12E). The early response encoding on DS trials occurs during the typical peak of DS-evoked excitation (before ~250 ms after cue onset; see Fig. 1D). Thus these results support our hypothesis that reward prediction propels the signal into a broad range above the threshold for promoting action, which is also reflected by the enhanced strength of coding related to the upcoming behavioral response specifically on trials in which reward is expected.

Intriguingly, during NS trials, behavioral response contributed considerably later than during DS trials. This contribution emerged after the peak cue-evoked excitation, suggesting that, unlike for DS trials, behavioral responses after the NS are not typically the result of firing reaching threshold during the early peak, but rather of a later integrative process that is not dependent on a large simultaneous burst of NAc neuronal activity. Taken together, these findings indicate that encoding of reward prediction and behavioral response probability are intimately linked within the same NAc neurons, although different mechanisms (with different time courses) may mediate the impact of DS- and NS-evoked firing on response probability.

DISCUSSION

NAc neurons are thought to integrate the reward-predictive aspects of stimuli and promote motor responses that allow subjects to take advantage of them (Freund et al. 1984; McGinty and Grace 2008; Mogenson et al. 1980; O’Donnell and Grace 1995). NAc activity may be specifically important for tasks in which cues elicit novel action sequences (i.e., taxic approach) that are uniquely dependent on mesolimbic dopamine (Nicola 2010, 2007, 2016). At the same time, approach probability is increased when a cue predicts reward; indeed, many NAc neurons are excited by cues that predict reward and elicit taxic approach (Day et al. 2006; du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014; Nicola et al. 2004a; Wan and Peoples 2006; Yun et al. 2004). Therefore, we hypothesized that NAc cue-evoked excitations are driven by upstream representations of cue value and, in turn, promote taxic approach, acting as a physiological substrate of the NAc’s limbic-motor interface function.

Cue-evoked excitations in the NAc precede taxic approach, and their magnitude predicts latency and speed (McGinty et al. 2013). Moreover, injection of dopamine receptor antagonists into the NAc increases the latency to initiate approach (Nicola 2010) while decreasing the magnitude of cue-evoked excitations (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014), supporting the idea that they drive the initiation of taxic approach. NAc neurons respond to both cues that predict reward (DSs) and cues that do not (NSs); although NS-evoked firing is, on average, lower than DS-evoked firing (Day et al. 2006; du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Nicola et al. 2004a), it is possible that this firing actually reflects the likelihood of a taxic approach response. If this were the case, we might conclude that NAc cue-evoked excitations do not, in fact, serve a limbic-motor interface function; rather, some of them serve a reward prediction function and others serve a parallel motor function. This “parallel encoding” hypothesis is supported by observations that the NAc can signal the predicted value of rewards even in the absence of taxic approach in humans (Delgado et al. 2000; Knutson et al. 2001, 2005; O’Doherty et al. 2004) and rodents (Goldstein et al. 2012; Roesch et al. 2009; Setlow et al. 2003).

If a parallel encoding framework best approximated reality, we would expect separate populations of cue-excited neurons to encode reward prediction and behavior; therefore, these populations could be disambiguated by their responses to reward-predictive cues to which the animal does not respond (DS/nonresponse) and non-reward-predictive cues to which the animal responds (NS/response). In contrast, the limbic-motor interface hypothesis predicts that cue-evoked excitations are influenced by both reward prediction (DS vs. NS) and behavioral response type (response vs. nonresponse). Our findings support the limbic-motor interface hypothesis and largely refute the parallel encoding hypothesis. Cue-excited neurons overwhelmingly fired more to the DS than the NS and when the animal responded to a cue than when no response occurred, and both of these factors contributed to firing in the majority of neurons. This suggests that the reward-predictive value of the stimulus determines the magnitude of NAc cue-evoked excitations, which in turn set the probability of a taxic approach response. Indeed, firing rate strongly predicted response likelihood independently of cue identity. Coupled with evidence that cue-evoked excitations depend on input from the basolateral amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and VTA (Ambroggi et al. 2008; du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; Ishikawa et al. 2008; Yun et al. 2004) and that these excitations cause the initiation of taxic approach (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014), we conclude that cue-excited neurons in the NAc causally connect value encoding in upstream structures with taxic approach.

If NAc reward prediction encoding directly influences the probability of a behavioral response, how can peak behavioral response encoding precede peak reward encoding? We speculate that there is an activity threshold beyond which the probability of a subsequent behavioral response is near 100%. Cue-evoked firing on DS trials was rarely below this threshold, whereas NS-evoked excitations rarely exceeded the threshold, as reflected by early encoding of response probability on DS but not NS trials. In contrast, in later time windows, the behavioral response was encoded during both trial types. Thus high early peak firing rates could easily trigger a behavioral response, whereas it might take longer for smaller excitations’ cumulative effect to drive a response, consistent with rats’ longer reaction times on NS trials compared with DS trials (du Hoffmann and Nicola 2014; McGinty et al. 2013; Nicola 2010; Nicola et al. 2004a). Our previous results (McGinty et al. 2013; Morrison and Nicola 2014) indicate that response probability increases with proximity to the lever at cue onset, suggesting that proximity promotes responding by increasing NAc cue-evoked excitations. We found that distance had its greatest effect on firing in an early time window, implying a proximity-driven increase in the number of neurons that fire above an early behavioral response threshold.

In contrast to the DS task, predicted reward magnitude was not encoded during forced-choice trials in the DM task. One possible explanation is that the differences in reward magnitude were difficult for the animal to detect; however, this is unlikely because animals typically chose large over small reward (Morrison and Nicola 2014). Instead, we note that, in the DS task, a given cue had the same reward-predictive value throughout training, whereas in the DM task, the volume of sucrose reward associated with each lever changed across blocks of trials. Previously, we found that the degree of NAc neurons’ cue-evoked excitations during choice trials was not consistently positively correlated with the magnitude of the chosen reward (Morrison and Nicola 2014). In the current study, we showed that this absence of encoding of predicted reward magnitude was found even in the forced-choice trials that preceded each free-choice block, in stark contrast to the robust reward prediction encoding observed in the DS task. Some cue-excited neurons exhibited overall greater or lesser firing during forced large-reward trials than during forced small-reward trials; however, if this were truly a stable representation of reward magnitude, then the direction of encoding should have been uniform across the session and across different lever-reward magnitude contingencies. Clearly, this was not observed.

A possible explanation for the near absence of consistent encoding of predicted reward in the DM task, compared with the DS task, rests on the different learning history of animals in the two tasks. In the DS task, a given cue had the same reward-predictive value throughout many trials and sessions, whereas in the DM task, the reward magnitude predicted by a given cue changed every 60 trials. NAc neurons may simply be unable to update their encoding of reward magnitude based on this relatively small number of cue-reward pairings. If this is the case, it suggests that the reward prediction encoding of NAc neurons participates in a “habit”-like stimulus-response process, because a signature feature of such processes is the slow updating of value representations (Adams 1982; Dayan and Balleine 2002). Directly supporting this idea, performance of NAc dopamine-dependent taxic approach tasks, including both sign tracking and the DS task, is resistant to outcome devaluation (Meffre et al. 2015; Morrison et al. 2015), another cardinal feature of habit-like behaviors (Adams and Dickinson 1981).