Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and nitric oxide (NO) are important regulators of gastrointestinal motility. The studies herein provide the cross talk between NO and H2S signaling to mediate smooth muscle relaxation and colonic transit. H2S inhibits phosphodiesterase 5 activity to augment cGMP levels in response to NO, which, in turn, via cGMP/PKG pathway, generates H2S. These studies suggest that interventions targeted at restring NO and H2S homeostasis within the smooth muscle may provide novel therapeutic approaches to mitigate motility disorders.

Keywords: muscle relaxation, signaling, phosphodiesterase 5, nitric oxide

Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), like nitric oxide (NO), causes smooth muscle relaxation, but unlike NO, does not stimulate soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) activity and generate cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate (cGMP). The aim of this study was to investigate the interplay between NO and H2S in colonic smooth muscle. In colonic smooth muscle from rabbit, mouse, and human, l-cysteine, substrate of cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), or NaHS, an H2S donor, inhibited phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) activity and augmented the increase in cGMP levels, IP3 receptor phosphorylation at Ser1756 (measured as a proxy for PKG activation), and muscle relaxation in response to NO donor S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), suggesting augmentation of cGMP/PKG pathway by H2S. The inhibitory effect of l-cysteine, but not NaHS, on PDE5 activity was blocked in cells transfected with CSE siRNA or treated with CSE inhibitor d,l-propargylglycine (dl-PPG), suggesting activation of CSE and generation of H2S in response to l-cysteine. H2S levels were increased in response to l-cysteine, and the effect of l-cysteine was augmented by GSNO in a cGMP-dependent protein kinase-sensitive manner, suggesting augmentation of CSE/H2S by cGMP/PKG pathway. As a result, GSNO-induced relaxation was inhibited by dl-PPG. In flat-sheet preparation of colon, l-cysteine augmented calcitonin gene-related peptide release in response to mucosal stimulation, and in intact segments, l-cysteine increased the velocity of pellet propulsion. These results demonstrate that in colonic smooth muscle, there is a novel interplay between NO and H2S. NO generates H2S via cGMP/PKG pathway, and H2S, in turn, inhibits PDE5 activity and augments NO-induced cGMP levels. In the intact colon, H2S promotes colonic transit.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and nitric oxide (NO) are important regulators of gastrointestinal motility. The studies herein provide the cross talk between NO and H2S signaling to mediate smooth muscle relaxation and colonic transit. H2S inhibits phosphodiesterase 5 activity to augment cGMP levels in response to NO, which, in turn, via cGMP/PKG pathway, generates H2S. These studies suggest that interventions targeted at restoring NO and H2S homeostasis within the smooth muscle may provide novel therapeutic approaches to mitigate motility disorders.

cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate (cGMP) generated via stimulation of nitric oxide (NO)-sensitive soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) activity plays an important role in smooth muscle relaxation (31, 38, 42). Intracellular cGMP levels are largely regulated by cGMP-hydrolyzing phosphodiesterase (PDEs) enzymes that break down cGMP (3, 10, 32). PDEs are a large group of structurally related enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of 3′,5′-cyclic nucleotides to the corresponding inactive nucleoside 5′-monophosphates (3, 10). cGMP-specific PDEs such as PDE5, PDE6, and PDE9 have much higher affinity for cGMP than for cAMP. PDE5 is the predominant cGMP-specific PDE expressed in gastrointestinal (GI) smooth muscle (32).

In the GI tract, H2S-synthesizing enzymes such as cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) and cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) have been shown to be expressed by enteric neurons, interstitial cells of Cajal, smooth muscle cells, and epithelial cells (20, 27–30, 41, 43). Endogenous generation of H2S via CSE and CBS has been demonstrated in different regions of the gastrointestinal tract (13, 16, 28, 30), and augmentation of spontaneous contractions in response to suppression of CSE or CBS supports a role for H2S as an endogenous signaling molecule in the regulation of gut motility (13, 31). In in vitro experiments, NaHS (a donor of H2S) and l-cysteine (a precursor of H2S generation) were used as a source of H2S. In general, NaHS has an inhibitory role on both spontaneous and agonist-induced contraction in different regions of GI tract in different species. NaHS inhibited agonist-induced contractions in circular muscle strips from mouse fundus and distal colon (8, 9), and in the ileum and jejunum of guinea pig, rat, and rabbit (16, 20, 36, 37, 41, 48). NaHS inhibited spontaneous circular smooth muscle contractions in rat and human colonic strips and peristaltic activity in the mouse small intestine and colon (12). NaHS, but not l-cysteine, inhibited spontaneous and agonist-induced contraction in rat ileal longitudinal muscle (36), whereas both NaHS and l-cysteine inhibited spontaneous and agonist-induced contraction in rat ileal circular muscle (37). A dual effect, a contraction at low (<200 µM) concentrations and relaxation at high (>200 µM) concentrations, of NaHS has been observed in the guinea pig and mouse stomach (15, 53). These studies suggest that the effect of H2S on contractile activity in GI tract is variable, which might reflect various effects of H2S on different targets. Several mechanisms for the inhibitory effect of H2S have been proposed, and these include activation of MLC phosphatase (8, 37), ATP-sensitive potassium channels (11, 12, 19, 37, 53), small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (SKCa) (12), and sodium channel activation (45).

Cross talk between NO/sGC/cGMP pathway and H2S has been previously reported in smooth muscle (4–7, 16, 22, 46). The regulation of intracellular cGMP is a key factor accounting for a positive interaction between H2S and NO. Endogenous H2S has been reported to be essential for NO-mediated increase of cGMP since CSE silencing inhibits the NO-induced cGMP accumulation (5). Exposure of rat aortic smooth muscle cells to different concentrations of NaHS leads to an increase in cGMP levels (5). Other studies report negative feedback regulations between NO and H2S (2, 14, 50). Release of NO from nNOS of enteric neurons and activation of NO/sGC/PKG pathway in smooth muscle is a physiological norm during descending relaxation phase of peristalsis (32, 42). Since NO and H2S use distinct mechanisms to regulate smooth muscle function, it is possible that there could be a synergistic or antagonist interaction between the mechanisms activated. In the present study, the link between NO and H2S in the regulation of smooth muscle cGMP/PKG pathway and a role for H2S in the regulation of colonic motility were examined. Our results demonstrate that in colonic smooth muscle H2S augments NO-induced relaxation, and the mechanism involves inhibition of NO-stimulated PDE5 activity and augmentation of cGMP levels. NO-induced relaxation was mediated, in part, via activation of CSE and generation of H2S. Our studies also showed that in colonic segments H2S increases colonic transit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The following chemicals for the preparation of Krebs solution were used: NaCl, KCl, KH2PO4, MgSO4, CaCl2, NaHCO3, and glucose; Crotalus atrox snake venom, cGMP, and other chemicals such as l-cysteine and sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) and d,l-propargylglycine (dl-PPG) were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Ferric chloride was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine sulfate were obtained from Alfa Aezer (Ward Hill, MA). Rp-8-Br-cGMPS was obtained from Alexis Corporation (Switzerland). S-nitrosoglutathione was obtained from Santa Cruz biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Western blotting materials and protein assay kit were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Polyclonal anti-PDE5 antibody and polyclonal anti-CSE antibody were obtained from Proteintech (Chicago, IL); [3H]cGMP and [125I]cGMP were obtained from Perkin Elmer Life sciences (Cambridge, MA). Antibody to phospho-IP3 receptor (Ser1756) was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

New Zealand White male rabbits (4 to 5 lb) were purchased from RSI Biotechnology (Clemmons, NC). Male C57BL/6 mice purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The animals were housed in the animal facility administered by the Division of Animal Resources, Virginia Commonwealth University. All procedures were approved and conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University. Normal human colon tissues were obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI, Philadelphia, PA), a nonprofit organization that provides human organs and tissue. The studies using human tissues from NDRI were approved as exempt from Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board.

Preparation of dispersed smooth muscle cells.

The colon was dissected out, emptied of contents and placed in oxygenated Krebs solution composed of 118 mM NaCl, 4.75 mM KCl, 1.19 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 2.54 mM CaCl2, 25 mM NaHCO3, and 11 mM glucose at 37°C and pH 7.4. Smooth muscle cells were isolated from the circular muscle layer of the colon from rabbit, mouse, and human by sequential enzymatic digestion, filtration, and centrifugation, as previously described (33–35). Briefly, colonic circular muscle strips were incubated for 30 min at 31οC in 15 ml of medium containing 120 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2.6 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES, and 14 mM glucose, 2.1% (vol/vol) Eagle’s essential amino acid mixture, 0.1% collagenase (type II), and 0.1% soybean trypsin inhibitor. After the 30-min digestion period, the cells that had spontaneously detached in collagenase containing medium were discarded, partly digested tissues were washed with 50 ml of collagenase-free medium, and muscle cells allowed to disperse spontaneously. The cells were harvested by filtration through 500 μm of Nitex and centrifuged twice at 350 g for 10 min. Dispersed smooth muscle cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum until they attained confluence and were then passaged once for use in various studies.

Assay for PDE5 activity.

PDE5 activity was measured in immunoprecipitates of PDE5 by the method of Wyatt et al. (51), as previously described (33). PDE5 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of dispersed rabbit colonic muscle cells (3 × 106 cells/ml) by using an anti-PDE5 antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were washed in a solution of 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA. The immunoprecipitates were then incubated for 15 min at 30°C in a reaction mixture containing 100 mM Mes (pH 7.5), 10 mM EDTA, 0.1 M magnesium acetate, 0.9 mg/ml BSA, 20 µM cGMP, and [3H]cGMP. The samples were boiled for 3 min, chilled, and then incubated at 30°C for 10 min in 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5) containing 10 µl of Crotalus atrox snake venom (10 µg/µl). The samples were added to DEAE-Sephacel A-25 columns, and the radioactivity in the effluent was counted. The results were expressed as counts per minute per milligram of protein.

Radioimmunoassay for cGMP.

cGMP production was measured by radioimmunoassay as described previously (33, 35). Briefly, muscle cells (3 × 106 cells) were treated with S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) for 10 min in the presence or absence of l-cysteine or NaHS pretreatment for 10 min, and the reaction was terminated with 10% trichloroacetic acid. The samples were centrifuged, and the supernatants extracted three times with water-saturated diethyl ether. The resulting aqueous phase was lyophilized and reconstituted in 500 µl of 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 6.2). The samples were acetylated with trimethylamine/acetic anhydride (2:1, vol/vol) for 30 min, and cGMP was measured in duplicate using 100-µl aliquots. The results were expressed as picomole per milligram of protein.

Transfection of CSE siRNA.

For transfection of siRNA, the cells were washed and cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics until they attained confluence and used after first passage in various experiments. The RNAi-Ready pSIREN-DNR-DsRed-Express Vector (BD Biosciences, Clontech) encoding CSE small-interfering RNA (Qiagen) was inserted between BamH1 and EcoR1 restriction sites and transfected into cultured smooth muscle cells with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. To check the specificity of the siRNA, empty vector without the siRNA sequence was used as a control. Successful knockdown of CSE protein was verified by Western blot analysis (35).

Measurement of phosphorylated inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate (IP3) receptor.

One milliliter of cells (2 to 3 × 106 cell/ml) was treated with GSNO (10 nM) for 10 min in the presence or absence of NaHS (1 mM) or l-cysteine (10 mM) pretreatment for 10 min and solubilized on ice for 1 h in medium containing 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM DTT, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.75% deoxycholate, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml of leupeptin, and 100 μg/ml of aprotinin. The proteins were resolved by SDS/PAGE and electrophoretically transferred on to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated for 12 h with phospho-specific antibodies to the IP3 receptor (Ser1756) (1:1,500) and then for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000). The protein bands were identified by enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (34, 35).

Measurement of H2S production.

Synthesis of H2S in smooth muscle from rabbit colon was measured using the method of Abe and Kimura (1) and modified by Qu et al. (40). Freshly obtained rabbit colonic smooth muscle cells were homogenized in ice-cold 50-mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0 (12% wt/vol), with a Polytron homogenizer. The homogenate (0.5 ml) and buffer (0.4 ml) were then cooled on ice for 10 min before l-cysteine (10 mM), and pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (2 mM) was added. The final volume was 1 ml. A smaller 2-ml tube containing a piece of filter paper (0.5 × 1.5 cm) soaked with zinc acetate (1%; 0.3 ml) was put inside the larger vial. The vials were then flushed with nitrogen gas for 20 s and capped with an airtight serum cap. The vials were then transferred to a 37°C shaking water bath, and after 90 min trichloroacetic acid (50%; 0.5 ml) was injected into the reaction mixture through the serum cap. The mixture was left to stand for another 60 min to allow for the trapping of evolved H2S by the zinc acetate.

The serum cap was then removed, and N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine sulfate (20 mM; 50 μl) in 7.2 mol/l HCl and FeCl3 (30 mM; 50 μl) in 1.2 mol/l HCl were added to the inner tube containing zinc acetate-soaked filter paper. After 20 min, absorbance at 670 nm was measured with a spectrophotometer. The calibration curve of absorbance vs. H2S concentration was obtained by using NaHS solution of varying concentrations as described previously (40). When NaHS is dissolved in water, HS− is released, which forms H2S with H+. H2S concentration is taken as 30% of the NaHS concentration in the calculation. The calibration curve in our studies was linear from 0 to 400 μM NaHS or 120 μM H2S. Smooth muscle homogenates were incubated with l-cysteine (10 mM) or GSNO (10 µM) in the presence or absence of CSE inhibitor d,l-propargylglycine (dl-PPG, 1mM). The amount of H2S released from tissue preparation was studied by spectrophotometry. The results are expressed as nmoles H2S/mg tissue.

Measurement of muscle relaxation in muscle strips.

Contractile activity of muscle strips was calculated as the maximum force generated in response to carbachol (CCh) (35). In some experiments, the strips were incubated with NO donor, GSNO, and dl-PPG for 10 min before CCh treatment. Strips obtained from the circular layer of rabbit colon were allowed to equilibrate to a passive tension of 1 g for at least 30 min before experiments were conducted, and bath buffer solution was changed every 15 min during equilibration and data collection. Only muscle strips that developed ∼2 g of tension above basal levels were used to test the effect of GSNO and PPG on CCh-induced contraction. Time control studies demonstrated that response to 10 μM CCh was reproducible following 2 h incubation in Krebs buffer. Muscle strips were used within 2 h after isolation. At the end of each experiment, the strips were blotted dry and weighed (tissue wet wt). Strip data were analyzed from within the Polyview software suite. All experiments were designed to compare treatment to control conditions. Paired t-tests were conducted in GraphPad (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), and significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

Measurement of muscle relaxation in dispersed muscle cells.

Cell lengths were measured by image scanning micrometry technique (33–35). All cell suspensions were used within 1 h after dispersion for cell length measurements. Freshly isolated muscle cells (0.4 ml containing 104/cell ml) from circular muscle layer of colon were preincubated for 10 min with different concentrations of GSNO, l-cysteine or NaHS, and then CCh was added for 30 s. The reaction was terminated with 1% acrolein. After termination, an aliquot of cell suspension was placed on a slide under a coverslip. The slide was scanned, and the length of first 50 cells randomly encountered was measured using a micrometer. The resting cell length was determined in control experiments in which muscle cells were incubated with 100 μl of 0.1% bovine serum albumin in the absence of CCh. Contraction is expressed as the absolute decrease in mean cell length (μm) from control cell length in the presence of contractile agonist. Relaxation is calculated as a percent decrease in contractile response in the presence of GSNO or GSNO plus l-cysteine or NaHS.

Calcitonin gene-related peptide assay.

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) release was measured in a 3- to 5-cm segment of mouse colon, opened to form a flat sheet, and pinned mucosal side up in a three-compartment organ bath as described in detail previously (21). The compartments were isolated by vertical partitions sealed with vacuum grease and equilibrated in Krebs-bicarbonate medium containing 118 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 25 mM NaH2CO3, 11 mM glucose, 0.1% BSA, and peptidase inhibitors (10 μM amastatin, 1 μM phosphoramidon) for 1 h. At the end this period, the medium was collected from the central sensory compartment, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. The bath was refilled with a medium, and a mucosal stroking stimuli was applied in the central compartment at a stimulus strength of either four or eight strokes. The stimulus was applied five times at 3-min intervals over a 15-min period, and after that the medium was collected from the central sensory compartment and stored at −80°C. After a 30-min equilibration period, during which the bathing medium was changed twice, the basal and mucosal stroking sequence was repeated in the presence of the 10 mM l-cysteine or 10 mM l-cysteine plus dl-PPG (1 mM) followed by collection of medium. The levels of CGRP in the medium were measured by radioimmunoassay using antibody RIK 6006 as described previously (21). The limit of detection of the assay was 2.6 fmol/ml and the IC50 was 39.2 ± 5.1 fmol/ml of original sample.

Measurement of pellet propulsion.

Isolated segments of the colon (5 to 6 cm) from mice were loosely pinned in an organ chamber as described previously (17, 21). After a 30-min of equilibration, a fine PE-10 tubing was placed in the segment from the anal end and advanced to just distal to an artificial fecal pellet placed at the orad end. The fecal pellets mimic native pellets in size and shape. The PE tubing was perfused with Krebs buffer (0.01 ml/min), the pellet allowed to move to the anal end, and the time to move through the colon measured. The velocity of propulsion of artificial fecal pellets was calculated as millimeter per second. The velocity for five pellets was measured. After determination of the velocity in the presence of Krebs buffer, the experiment was repeated by changing the perfusate to Krebs buffer containing 10 mM l-cysteine.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE of n, where n represents one sample from one animal for single experimental replicate. Each experiment was performed on cells and tissues obtained from different animals. Differences were analyzed by Student’s t-test and considered significant with a probability of P < 0.05. Regression analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5, a statistical software program (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

Augmentation of NO-induced relaxation by H2S in isolated muscle cells.

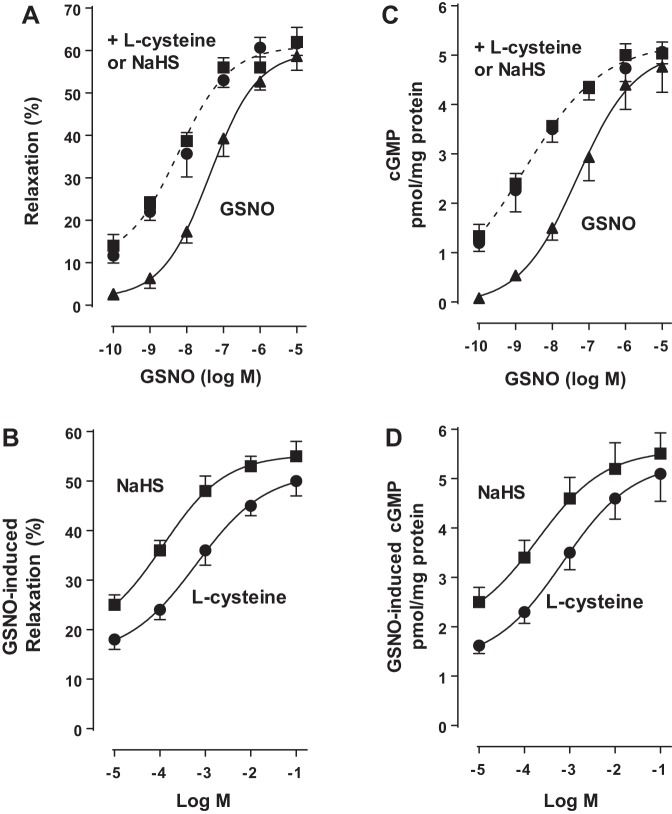

Previous studies in dispersed muscle cells showed that relaxation in response to NO is mediated via activation of sGC/cGMP/PKG pathway (32). Treatment of dispersed colonic smooth muscle cells with different concentration of NO donor GSNO (0.1 nM to 10 µM) induced relaxation in a concentration-dependent fashion with an EC50 of 50 nM and maximum relaxation of 58 ± 3% with 10 µM of GSNO. Treatment of colonic smooth muscle cells with GSNO in the presence of l-cysteine (10 mM) and NaHS (1 mM) augmented NO-induced relaxation, shifting the concentration-response curve to left with an EC50 of 5 nM and maximum relaxation of 65 ± 4% with 0.1 to 1 µM GSNO (Fig. 1A). Addition of different concentrations of l-cysteine (10 µM–100 mM) or NaHS (10 µM–100 mM) caused concentration-dependent augmentation of relaxation in response to submaximal concentrations of GSNO (10 nM) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Augmentation of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO)-induced muscle relaxation and cyclic guanosine 5′-monophosphate (cGMP) formation by l-cysteine and NaHS in colonic smooth muscle. A: dispersed muscle cells from rabbit colon were treated with increasing concentrations of GSNO (0.1 nM to 10 µM) for 10 min and then treated with carbachol (CCh, 1 µM) for 30 s. In some experiments, cells were cotreated with GSNO and l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) for 10 min and then treated with CCh (0.1 µM) for 30 s. B: dispersed muscle cells from rabbit colon were treated with submaximal concentrations of GSNO (10 nM) in the presence or absence of different concentrations of l-cysteine (0.1 µM to 100 mM) or NaHS (0.1 µM to 100 mM) for 10 min and then treated with CCh (1 µM) for 30 s. Muscle cell length was measured by scanning micrometry. Contraction by CCh was calculated as a percent decrease in muscle cell length from control cell length (35 ± 5% decrease in cell length from the basal cell length 97 ± 5 µm). Relaxation in response to GSNO in the presence or absence of l-cysteine or NaHS was expressed as the percent decrease in CCh-induced contraction. Values are means ± SE of four experiments. C: dispersed muscle cells from rabbit colon were treated with increasing concentrations of GSNO (0.1 nM to 10 µM) in the presence or absence of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) for 10 min. D: dispersed muscle cells from rabbit colon were treated with submaximal concentrations of GSNO (10 nM) in the presence or absence of different concentration of l-cysteine (0.1 to 100 mM) or NaHS (0.1 µM to 100 mM) for 10 min. cGMP levels were measured by radioimmunoassay using [125I]cGMP. Results are expressed as picomole per milligrams of protein. Values are means ± SE of five experiments.

Augmentation of cGMP/PKG pathway by H2S in isolated muscle cells.

We next investigated the effect of H2S on GSNO-induced cGMP levels. Treatment of dispersed colonic smooth muscle cells with different concentrations of GSNO (0.1 nM to 10 µM) caused an increase in cGMP levels in a concentration-dependent fashion with an EC50 of 40 nM and maximum response (4.7 ± 0.6 pmol/mg protein above basal levels of 0.5 ± 0.09 pmol/mg protein) at 10 µM GSNO. Treatment of cells with GSNO in the presence of l-cysteine (10 mM) and NaHS (1 mM) augmented NO-induced cGMP, shifting the concentration-response curve to left with an EC50 value of 1 nM and maximum response (5.1 ± 0.03 pmol/mg protein above basal levels of 0.5 ± 0.09 pmol/mg protein) at 1 µM GSNO (Fig. 1C). Addition of different concentrations of l-cysteine or NaHS caused concentration-dependent augmentation of cGMP levels in response to submaximal concentrations of GSNO (10 nM) (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that H2S augments relaxation in response to NO and the mechanism involves augmentation of cGMP levels.

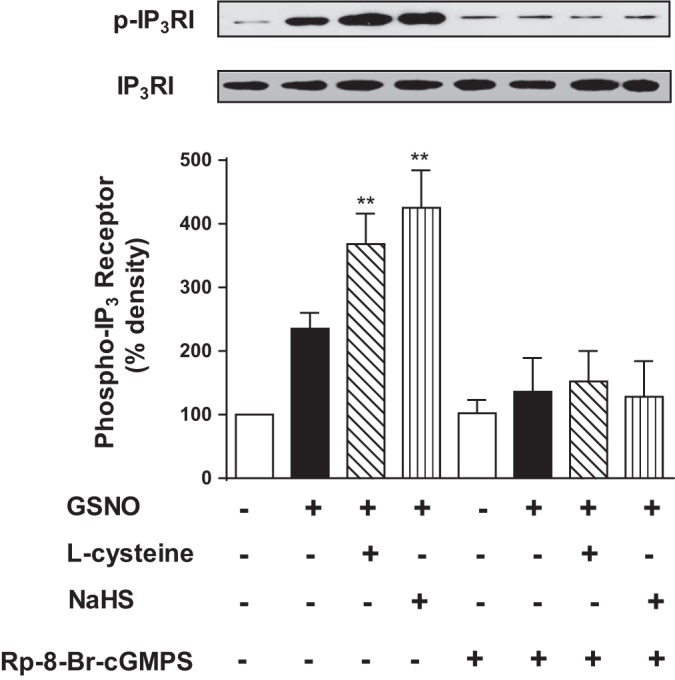

Previous studies in smooth muscle have shown that inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) was phosphorylated at Ser1756 in response to activation of PKG (23, 34). Treatment of cells with GSNO (10 nM) caused an increase in the phosphorylation of IP3R at Ser1756, measured as a proxy for PKG activity, and the effect of GSNO on IP3R phosphorylation was further augmented in the presence of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) (Fig. 2). The results are consistent with augmentation of GSNO-induced cGMP levels by l-cysteine or NaHS. The effect of GSNO in the presence or absence of l-cysteine or NaHS on IP3R phosphorylation was blocked by a PKG inhibitor, Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (10 µM), suggesting that both l-cysteine and NaHS converge on PKG to mediate IP3R phosphorylation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Augmentation of GSNO-induced PKG activity (IP3 receptor phosphorylation) by l-cysteine and NaHS in colonic smooth muscle. Dispersed muscle cells from rabbit colon were treated with GSNO (10 nM) in the presence or absence of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) for 10 min. In some experiments, cells were pretreated with PKG inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (10 µM) before the addition of GSNO in the presence or absence of l-cysteine or NaHS. IP3 receptor phosphorylation at Ser1756, a proxy for PKG activity, was measured using phospho-specific (Ser1756) antibody. Results are expressed as percent density of phosphorylated protein bands. Values are means ± SE of four experiments. Representative images of four separate experiments were shown in the figure. **P < 0.01, significant augmentation of GSNO-induced IP3 receptor phosphorylation.

Inhibition of PDE5 activity by H2S in isolated muscle cells.

Previous studies have shown that cGMP is hydrolyzed predominantly by PDE5 in GI smooth muscle (33). Augmentation of NO-induced cGMP levels by H2S could be due to increase in NO-induced sGC activity and/or decrease in PDE5 activity. Treatment of cells with l-cysteine (10 mM) and NaHS (1 mM) in the absence of GSNO but in the presence of a nonspecific PDE inhibitor, isobutyl methyl xanthine (100 µM), had no effect on cGMP levels (0.83 ± 0.09 pmol/mg protein vs. 0.92 ± 0.14 with l-cysteine or 1.1 ± 0.15 pmol/mg protein), suggesting that unlike NO, H2S had no effect on sGC activity (7–10, 17, 22, 43). We examined the hypothesis that augmentation of NO-induced cGMP in response to H2S is due to inhibition of NO-stimulated PDE5 activity and suppression of cGMP hydrolysis.

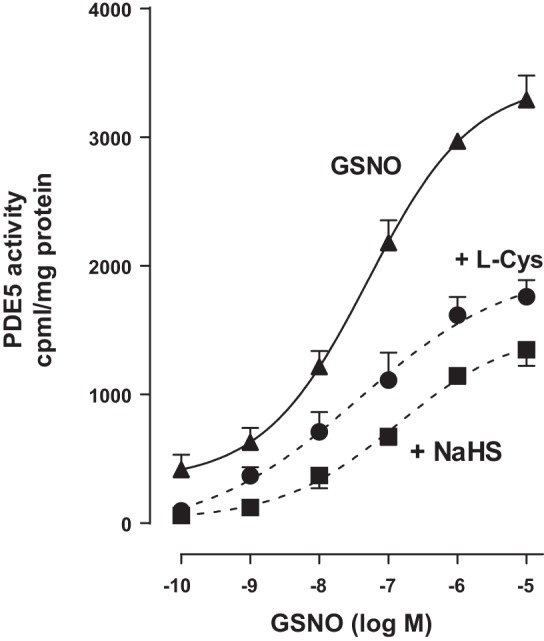

Treatment of colonic muscle cells with different concentration of GSNO (0.1 nM to 10 µM) for 10 min caused an increase in PDE5 activity in a concentration-dependent manner with an EC50 of 62 nM and maximum activity with 10 µM GSNO (3,479 ± 634 cpm/mg protein; P < 0.001) above basal levels (264 ± 43 cpm/mg protein). Treatment of muscle cells with GSNO in the presence of l-cysteine (10 mM) and NaHS (1 mM) attenuated GSNO-induced PDE5 activity, shifting the concentration-response curve to the right (Fig. 3). These results suggest that augmentation of GSNO-induced cGMP levels and relaxation by H2S is due to inhibition of PDE5 activity and suppression of cGMP hydrolysis.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of GSNO-stimulated PDE5 activity by l-cysteine and NaHS. Dispersed rabbit colonic smooth muscle cells were treated with GSNO (0.1 nM to 10 µM) for 10 min. PDE5 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of muscle cells, and PDE5 activity was measured using [3H]cGMP as the substrate. In some experiments, muscle cells were pretreated with l-cysteine (10 mM) and NaHS (1 mM) for 10 min followed by treatment with GSNO. The increase in PDE5 activity in response to GSNO was measured by an increase in [3H]GMP levels in the effluent, and the results are expressed as counts/min per milligram protein above basal [3H]GMP levels (264 ± 43 cpm/mg protein). Values are means ± SE of four experiments.

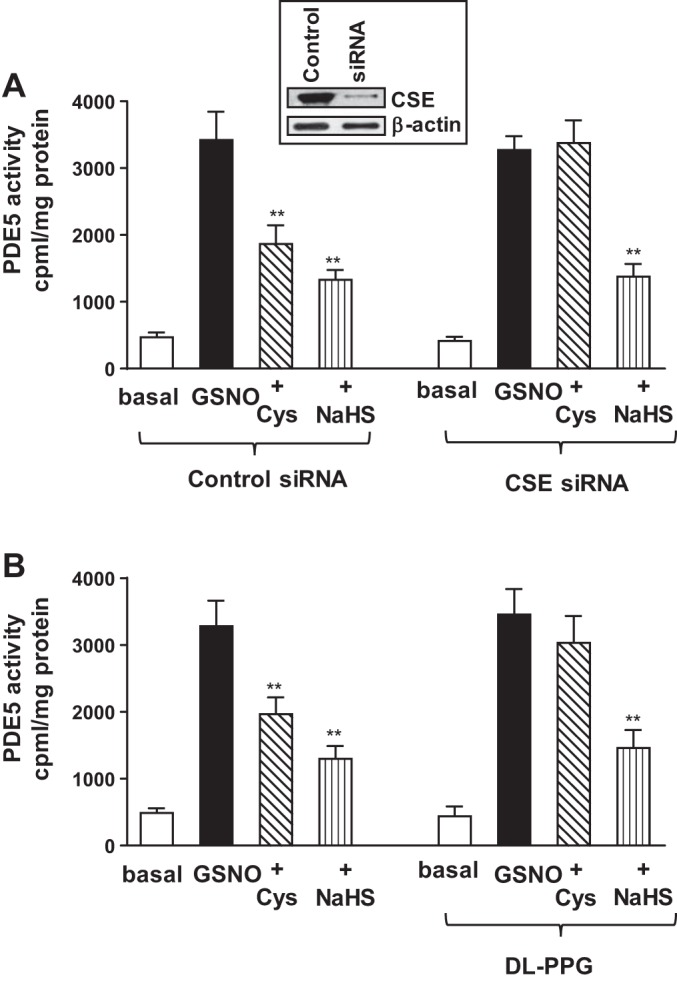

The involvement of endogenous H2S generation in the inhibition of PDE5 activity by l-cysteine was examined by two approaches: 1) transfection of cultured muscle cells with CSE-specific siRNA, and 2) treatment of dispersed muscle cells with a selective CSE inhibitor, dl-PPG. GSNO induced a significant increase in PDE5 activity in cultured muscle cells (3,735 ± 450 cpm/mg protein; P < 0.001) that is similar to the increase in dispersed muscle cells. Addition of l-cysteine (10 mM) caused significant inhibition of GSNO-stimulated PDE5 activity (48 ± 5% inhibition) in cells transfected with control siRNA. The inhibitory effect of l-cysteine was blocked in cells transfected with CSE-specific siRNA, suggesting that the effect of l-cysteine was mediated via activation of CSE (Fig. 4A). Addition of NaHS (1 mM) also caused a significant inhibition of GSNO-stimulated PDE5 activity in cells transfected with control siRNA (64 ± 6% inhibition). The inhibitory effect of NaHS, however, was not affected in cells transfected with CSE-specific siRNA (65 ± 8% inhibition) (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of GSNO-stimulated PDE5 activity by l-cysteine via activation of cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE). A: cultured rabbit colonic muscle cells were transfected with control siRNA or CSE-specific siRNA for 48 h. Cells were treated with GSNO (10 µM) for 10 min in the presence or absence of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) pretreatment for 10 min. PDE5 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of muscle cells, and PDE5 activity was measured using [3H]cGMP as the substrate. The increase in PDE5 activity in response to GSNO was measured by an increase in [3H]GMP levels in the effluent, and the results are expressed as counts/min per milligram protein. Values are means ± SE of four experiments. **P < 0.01, significant inhibition of GSNO-induced PDE5 activity. Expression of CSE in cells transfected with control siRNA or CSE siRNA was analyzed by Western blot analysis (inset). B: dispersed muscle cells from rabbit colon were treated with GSNO (10 µM) for 10 min in the presence or absence of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) pretreatment of 10 min. In some experiments, cells were treated with l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) in the presence of CSE inhibitor dl-PPG (1 mM). PDE5 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of muscle cells, and PDE5 activity was measured using [3H]cGMP as the substrate. The increase in PDE5 activity in response to GSNO was measured by an increase in [3H]GMP levels in the effluent, and the results are expressed as counts/min per milligram protein. Values are means ± SE of four experiments. **P < 0.01, significant inhibition of GSNO-induced PDE5 activity.

Similar studies were performed using dl-PPG (1 mM) in the presence of both l-cysteine and NaHS in dispersed muscle cells. Addition of l-cysteine (10 mM) caused significant inhibition of GSNO-stimulated PDE5 activity (43 ± 6% inhibition). The inhibitory effect of l-cysteine was blocked in the presence of dl-PPG (1 mM) (8 ± 7% inhibition, not significant) (Fig. 4B). Addition of NaHS (1 mM) also caused a significant inhibition of GSNO-stimulated PDE5 activity in control cells (62 ± 4% inhibition). The inhibitory effect of NaHS, however, was not affected by the presence of dl-PPG (58 ± 7% inhibition) (Fig. 4B). These results provide evidence for the involvement of CSE, via generation of H2S, in inhibition of PDE5 activity by l-cysteine.

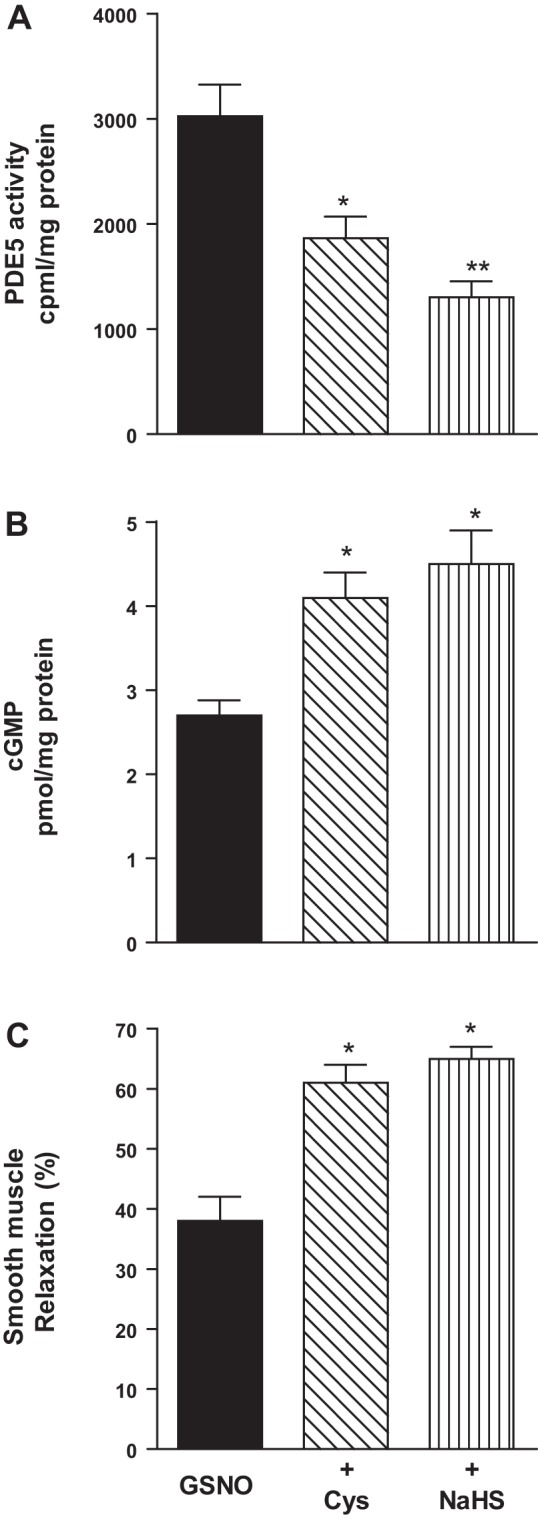

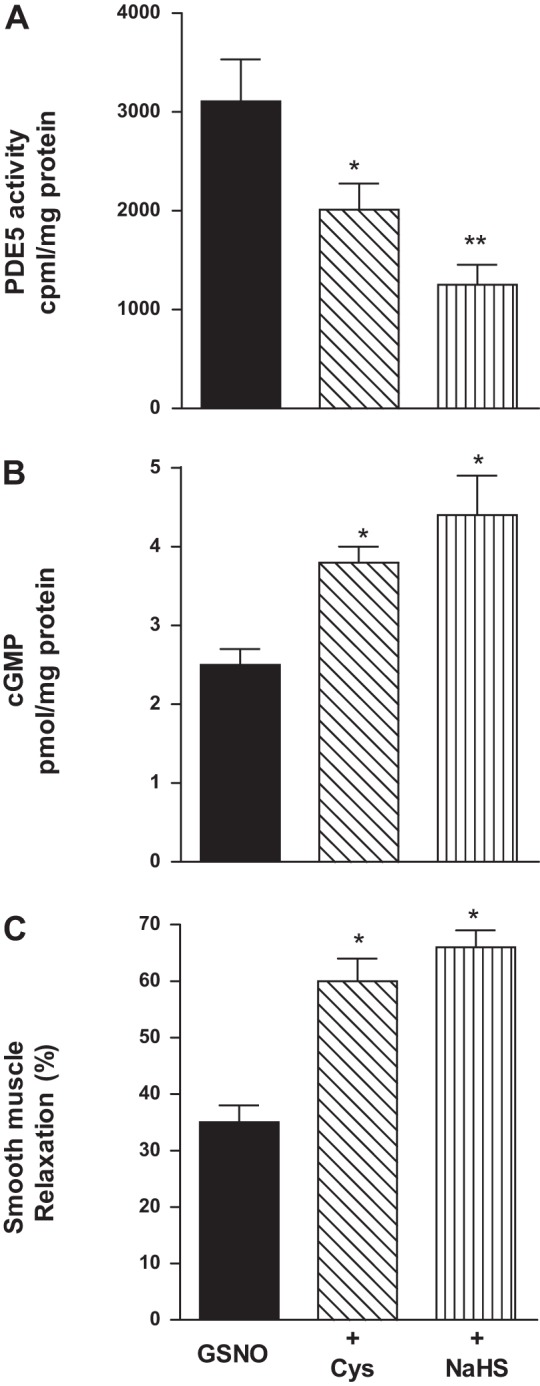

Addition of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) also inhibited PDE5 activity and augmented cGMP levels and muscle relaxation in response to GSNO in colonic muscle cells isolated from mouse and human (Figs. 5 and 6). In mouse colonic muscle cells, l-cysteine and NaHS inhibited GSNO-stimulated PDE5 activity (37 ± 5 and 44 ± 4% inhibition) and augmented cGMP levels (49 ± 7 and 63 ± 4%) and relaxation (59 ± 5 and 70 ± 7%) (Fig. 5). In human mouse colonic muscle cells, l-cysteine and NaHS inhibited GSNO-stimulated PDE5 activity (35 ± 3 and 58 ± 6% inhibition) and augmented cGMP levels (51 ± 6 and 73 ± 8%) and relaxation (64 ± 6 and 84 ± 8%) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of GSNO-induced PDE5 activity and augmentation of cGMP formation and relaxation by l-cysteine and NaHS in mouse colonic muscle cells. A: dispersed mouse colonic smooth muscle cells were treated with GSNO (10 µM) for 10 min in the presence or absence of with l-cysteine (10 mM) and NaHS (1 mM) pretreatment for 10 min. PDE5 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of muscle cells, and PDE5 activity was measured using [3H]cGMP as the substrate. The increase in PDE5 activity in response to GSNO was measured by an increase in [3H]GMP levels in the effluent, and the results are expressed as counts/min per milligram protein above basal [3H]GMP levels (238 ± 36 cpm/mg protein). Values are means ± SE of four experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 significant inhibition of GSNO-induced PDE5 activity. B: dispersed muscle cells from mouse colon were treated with submaximal concentrations of GSNO (100 nM) for 10 min in the presence or absence of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) pretreatment for 10 min. cGMP levels were measured by radioimmunoassay using [125I]cGMP. Results are expressed as picomole per milligrams of protein. Values are means ± SE of five experiments. *P < 0.05, significant augmentation of GSNO-induced cGMP levels. C: dispersed muscle cells from mouse colon were treated with GSNO (100 nM) in the presence or absence of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) for 10 min and then treated with CCh (1 µM) for 30 s. Muscle cell length was measured by scanning micrometry. Contraction by CCh was calculated as a percent decrease in muscle length from control cell length (32 ± 4% decrease in cell length from the basal cell length 112 ± 7 µm). Relaxation in response to GSNO in the presence or absence of l-cysteine or NaHS was expressed as the percent decrease in CCh-induced contraction. Values are means ± SE of four or five experiments. *P < 0.05, significant augmentation of GSNO-induced relaxation.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of GSNO-induced PDE5 activity and augmentation of cGMP formation and relaxation by l-cysteine and NaHS in human colonic muscle cells. A: dispersed human colonic smooth muscle cells were treated with GSNO (10 µM) for 10 min in the presence or absence of with l-cysteine (10 mM) and NaHS (1 mM) pretreatment for 10 min. PDE5 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of muscle cells, and PDE5 activity was measured using [3H]cGMP as the substrate. The increase in PDE5 activity in response to GSNO was measured by an increase in [3H]GMP levels in the effluent, and the results are expressed as counts/min per milligram protein above basal [3H]GMP levels (286 ± 45 cpm/mg protein). Values are means ± SE of four experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 significant inhibition of GSNO-induced PDE5 activity. B: dispersed muscle cells from human colon were treated with GSNO (100 nM) for 10 min in the presence or absence of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) pretreatment for 10 min. cGMP levels were measured by radioimmunoassay using [125I]cGMP. Results are expressed as picomole per milligrams of protein. Values are means ± SE of five experiments. *P < 0.05, significant augmentation of GSNO-induced cGMP formation. C: dispersed muscle cells from human colon were treated with GSNO (100 nM) in the presence or absence of l-cysteine (10 mM) or NaHS (1 mM) for 10 min and then treated with CCh (1 µM) for 30 s. Muscle cell length was measured by scanning micrometry. Contraction by CCh was calculated as a percent decrease in muscle length from control cell length (32 ± 4% decrease in cell length from the basal cell length 95 ± 4 µm). Relaxation in response to GSNO in the presence or absence of l-cysteine or NaHS was expressed as the percent decrease in CCh-induced contraction. Values are means ± SE of four experiments. *P < 0.05, significant augmentation of in GSNO-induced relaxation.

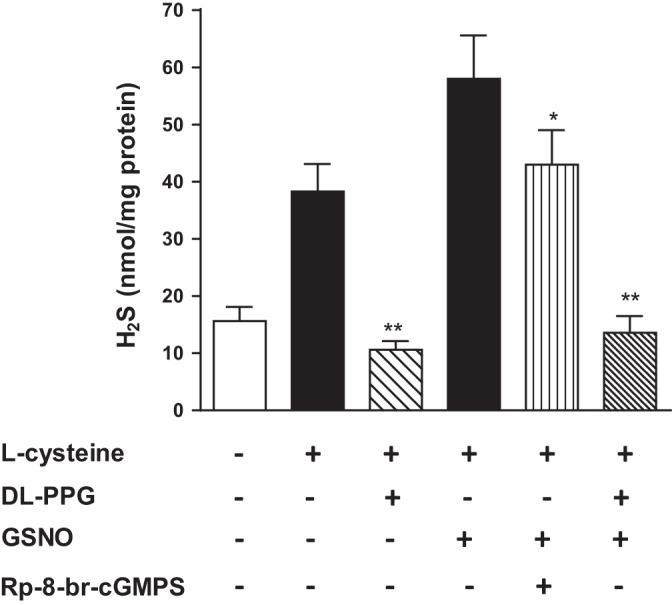

H2S production in colonic smooth muscle.

Incubation of smooth muscle homogenates from rabbit colon with l-cysteine (10 mM) caused a significant increase in H2S production (145 ± 24% increase above basal levels of 15.6 ± 2.5 nmol H2S/mg tissue). l-Cysteine-induced H2S production was blocked by the CSE inhibitor dl-PPG (1 mM) (Fig. 7). These studies show that endogenous H2S production from the colonic smooth muscle is generated by the activation of CSE and consistent with the expression of CSE in smooth muscle cells of rabbit colon (35). l-Cysteine-induced increase in H2S production was significantly augmented by GSNO (10 µM) (88 ± 6% increase above l-cysteine-induced increase), and the effect of GSNO on l-cysteine-induced H2S production was attenuated by Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (19 ± 4% increase above l-cysteine-induced increase) and blocked in the presence of dl-PPG (Fig. 7). These results suggest that activation of sGC/cGMP/PKG pathway in response to GSNO stimulates CSE activation and H2S production, which in turn facilitates relaxation via inhibition of PDE5 activity and augmentation of cGMP/PKG pathway.

Fig. 7.

Stimulation of CSE activity in response to l-cysteine and GSNO in colonic smooth muscle. Homogenates prepared from rabbit colonic smooth muscle were treated with l-cysteine (10 mM) for 90 min in the presence or absence of CSE inhibitor d,l-propargylglycine (dl-PPG, 1 mM). In some experiments, homogenates were treated with l-cysteine (10 mM) and GSNO (10 µM) in the presence or absence of PKG inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (10 µM). Formation of H2S was measured by spectrophotometry and expressed as nanomole per milligrams tissue. Values are means ± SE of seven experiments. **P < 0.01, significant inhibition of l-cysteine- or GSNO-induced H2S production by dl-PPG; *P < 0.05, significant inhibition of GSNO-induced H2S production by Rp-8-Br-cGMPS.

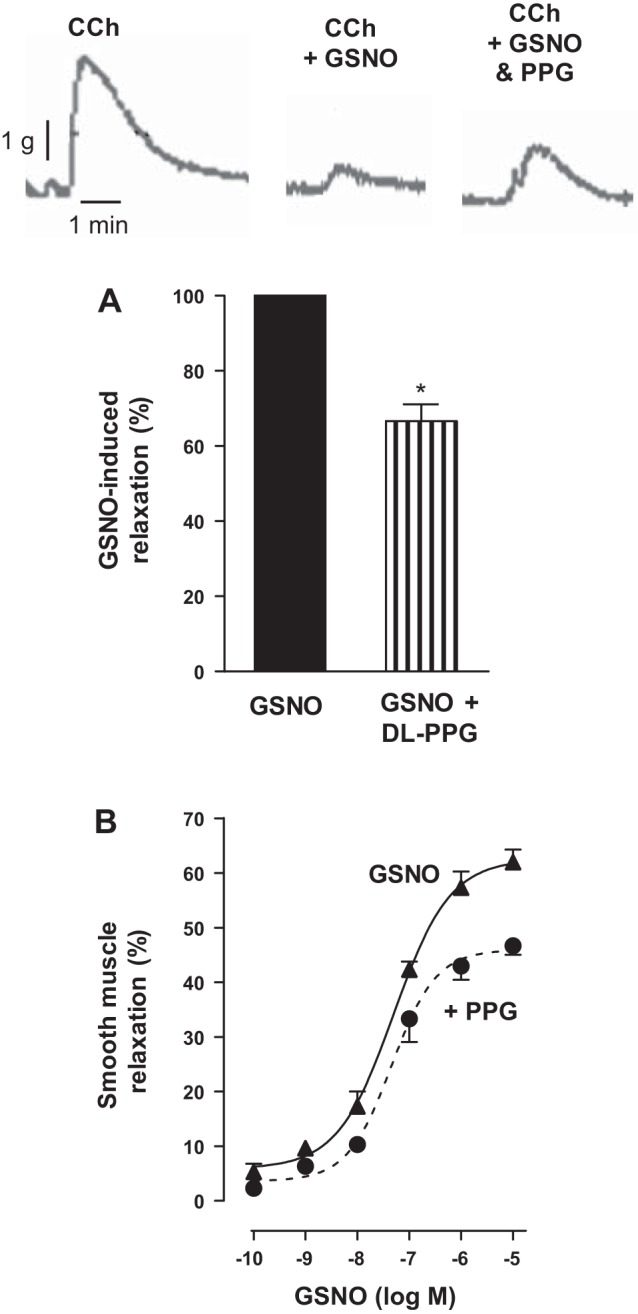

Inhibition of GSNO-induced relaxation by dl-PPG.

The involvement of CSE/H2S pathway in mediating relaxation in response to GSNO was examined in muscle strips and dispersed muscle cells. GSNO-induced relaxation was measured in the presence or absence of dl-PPG (1 mM). CCh-induced contraction was inhibited (i.e., relaxation) in the presence of GSNO (10 µM), and the inhibition by GSNO was attenuated by treatment of strips with dl-PPG (33 ± 4% inhibition of GSNO response) (Fig. 8A). Treatment of dispersed colonic smooth muscle cells with GSNO induced relaxation in a concentration-dependent fashion with an EC50 of 45 nM and maximum relaxation of 63 ± 5% with 10 µM of GSNO. Treatment of colonic smooth muscle cells with GSNO in the presence of dl-PPG attenuated GSNO-induced relaxation, shifting the concentration-response curve to the right with a maximal relaxation of 47 ± 4% with 10 µM GSNO (Fig. 8B). These results suggest GSNO-induced relaxation was partly due to H2S production via activation of CSE.

Fig. 8.

Partial reversal of NO-induced relaxation by CSE inhibitor d,l-propargylglycine (dl-PPG) in colonic smooth muscle. A: muscle strips from the rabbit colon were allowed to equilibrate at a passive tension of 1 g for 30 min and then treated with CCh (10 µM). In some experiments, the strips are incubated with GSNO (10 µM) in the presence or absence of CSE inhibitor dl-PPG (1 mM) for 10 min. Relaxation was measured as a percent decrease of contraction (measured as maximal area under the curve induced by CCh) in response to GSNO in the presence or absence of dl-PPG. Values are expressed as percent maximum of GSNO-induced relaxation. Values are means ± SE of four experiments. *P < 0.05, significant inhibition of GSNO-induced relaxation by dl-PPG. Contractile recording shows the inhibition of CCh-induced contraction by GSNO and partial reversal of GSNO-induced inhibition by dl-PPG. B: dispersed muscle cells from rabbit colon were treated with different concentrations of GSNO (0.1 nM to 10 µM) in the presence or absence of dl-PPG (1 mM) for 10 min and then treated with CCh (1 µM) for 30 s. Muscle cell length was measured by scanning micrometry. Contraction by CCh was calculated as a percent decrease in muscle length from control cell length (35 ± 5% decrease in cell length from the basal cell length 102 ± 4 µm). Relaxation in response to GSNO in the presence or absence of dl-PPG was expressed as the percent decrease in CCh-induced contraction. Values are means ± SE of four experiments.

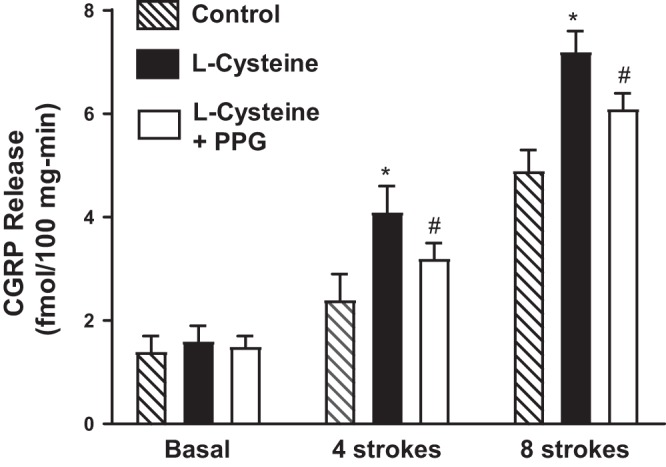

Release of calcitonin gene-related peptide in flat-sheet preparations.

Previous studies in mice and other species have shown that activation of sensory neurons in response to mucosal stimulation initiates a peristaltic reflex and colonic motility (21). CGRP release in response to stimulation is a marker of activation of the sensory neurons (21). Four or eight strokes of mucosa increased CGRP release above basal release (69 ± 5 and 248 ± 20% increase above basal levels of 1.4 ± 0.3 fmol·100 mg−1·min−1). Addition of l-cysteine to the central compartment of the mouse colonic flat-sheet preparations did not affect the basal release of CGRP (Fig. 9). However, CGRP release in response to both four and eight stroking was further increased in the presence of l-cysteine (174 ± 23 and 398 ± 42%) (Fig. 9). The augmentation in stroking-induced CGRP release in the presence of l-cysteine was partially attenuated by dl-PPG. The l-cysteine-induced augmentation at four strokes was reduced by 35 ± 6%, and the l-cysteine-induced augmentation of the response to eight strokes was reduced by 52 ± 8%. These results raise the possibility that the increase in CGRP release in response to l-cysteine would alter colonic transit.

Fig. 9.

Increase in calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) release. CGRP release in the central compartment following mucosal stimulation in the presence or absence of l-cysteine (10 mM) alone or l-cysteine plus dl-PPG (10 mM) was measured as described in materials and methods. Basal release represents control release in the absence of mucosal stimulation. Release in the presence of l-cysteine was represented by solid bars. Values are means ± SE of three experiments. *P < 0.05, significant increase in release in the presence of l-cysteine. #P < 0.05, significant inhibition of l-cysteine effect by dl-PPG.

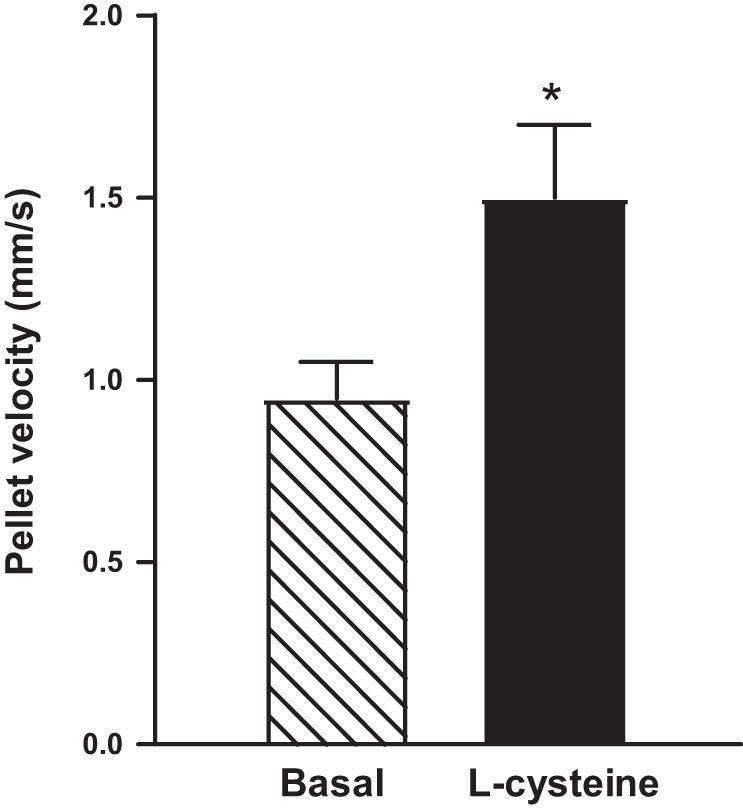

Pellet propulsion in intact colonic segments.

The effect of l-cysteine on colonic transit was tested ex vivo by measuring the velocity of pellet propulsion in the absence or presence of l-cysteine (10 mM) in isolated colonic segments of mice. Artificial fecal pellets placed into the orad end of colonic segments in the absence of l-cysteine propelled distally at a velocity of 0.95 ± 0.10 mm/s. The velocity of propulsion of the same artificial fecal pellets in colonic segments in the presence of l-cysteine was augmented to 1.50 ± 0.2 mm/s, a 57 ± 8% increase in the velocity of propulsion (P < 0.05, n = 4, where n represents one preparation from one animal and velocity for five pellets was measured in each preparation) (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Velocity of propulsion of fecal pellets in colonic segments from mouse colon. Artificial fecal pellets were inserted into the orad end of intact segments isolated from mouse colon, and the time to traverse a defined distance recorded. The velocity of propulsion of five pellets was calculated. Consistent with augmentation of relaxation of smooth muscle, the velocity of fecal pellet propulsion was increased by 10 mM l-cysteine. Values are mean ± SE of four experiments. *P < 0.05 significant augmentation of colonic propulsion by l-cysteine.

DISCUSSION

Although the importance of H2S as a signaling molecule mediating smooth muscle relaxation is known, unlike the well-established effect on activation of KATP channels in the cardiovascular system (46, 49, 52), the mechanism of action of H2S in the GI tract was shown to be site specific and species dependent. Relaxation in mouse gastric fundus is independent of K+ channel activation (8). In guinea pig antrum, inhibition of spontaneous contractions by high concentrations (0.3 to 1.0 mM) of NaHS are dependent on KATP channel activation, whereas an increase in basal tension by low concentrations of NaHS is dependent on inhibition of voltage-gated K+ channels (53). A direct effect of NaHS on KATP channels in mouse colonic smooth muscle cell was also demonstrated (11, 19). In addition to the direct effect, inhibitory effect on nNOS responsible for the generation of NO (44), and on ICC, responsible for pacemaker activity (39) has been reported. These data suggest that the effects of H2S is variable, which is consistent with the effects on H2S on various cells types and targets in the GI tract. This is further confounded by the interaction of H2S with NO, a well-established signaling molecule in muscle relaxation. Contrary to the early notions that signaling pathways activated by NO and H2S are independent, recent studies to understand the interaction of NO and H2S to mediate interdependent biological actions suggests that there exists a cross talk between H2S and NO (4–7, 16, 22, 46). Studies have shown both stimulation and inhibition of NO pathway by H2S: for example, augmentation of iNOS expression (18) and inhibition of eNOS activity (2, 24) and nNOS activity (25) and NO function (26). In the mouse colon, endogenous H2S acting in an autocrine fashion is an inhibitor of NO generation from nNOS (44).

Our results in the present study using isolated colonic smooth muscle cells demonstrated that the effect of NO is augmented by H2S. The effect of H2S to augment NO-induced relaxation arises from the ability of H2S to enhance cGMP levels by diminishing its degradation via inhibition of cGMP-specific PDE5 activity. The evidence was based on measurements of both cGMP levels and PDE5 activity in response to GSNO in the presence or absence of l-cysteine or NaHS. Although l-cysteine or NaHS had no effect on cGMP levels in the absence of NO, both l-cysteine and NaHS caused augmentation of NO-induced cGMP levels, PKG activity, and muscle relaxation. Both l-cysteine and NaHS inhibited PDE5 activity and augmented cGMP levels and muscle relaxation in a concentration-dependent fashion. Inhibition of PDE5 activity by l-cysteine was blocked by suppression of CSE expression or inhibition of CSE activity, suggesting that l-cysteine-mediated effects are due to activation of CSE. Similar inhibition of PDE5 activity and augmentation of cGMP levels and relaxation was observed in colonic smooth muscle from rabbit, mouse, and human. H2S also augments the PKG pathway downstream of cGMP, and this is evident from the augmentation of IP3R phosphorylation at Ser1756 (measured as a proxy for PKG activity) by both l-cysteine and NaHS. Blockade of phosphorylation in response to l-cysteine or NaHS by the PKG inhibitor Rp-8-Br-cGMPS suggests that the augmentation by l-cysteine or NaHS is mediated via activation of PKG. NO and H2S converge on PKG to mediate relaxation. These studies suggest that H2S amplifies NO-induced relaxation in colonic smooth muscle by the inhibition of cGMP-specific PDE5 activity. H2S augments cGMP levels on concurrent release of NO, NO-induced activation of sGC, and generation of cGMP. The exact mechanism by which H2S inhibits PDE5 activity awaits further study. The possible mechanisms include S-sulfhydration, a posttranslational modification through which H2S is known to alter the targets such as KATP channels, or binding to Zn and altering the enzyme activity, as H2S is known to bind Zn, and PDE5s are Zn-containing enzymes (3, 47).

Previous studies have shown an interplay between NO and H2S. A role for PKG in H2S mediated relaxation was demonstrated using PKG-I null mice (4). Relaxation to both NaHS and l-cysteine were reduced in vascular smooth muscle of PKG-I null mice, demonstrating that endogenous PKG-I is partially responsible for NaHS and l-cysteine-stimulated vasodilation (38). Studies by Bucci et al. (5) have shown that incubation of cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells with NaHS caused an increase in cGMP levels. Blockade of CSE activity by dl-PPG or suppression of CSE mRNA led to a significant reduction of cGMP levels. Overexpression of CSE, in contrast, led to an increase in intracellular cGMP levels. Further studies showed that NaHS significantly inhibits phosphodiesterase activity in vitro and causes a reduction in the breakdown of cGMP. Coletta et al. (7) reported that H2S and NO are mutually dependent to regulate endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. These reports show that NaHS inhibits purified PDE5 activity as effectively as sildenafil with an IC50 of 1.55 μM. Exposure of endothelial cells to H2S increases intracellular cGMP in an NO-dependent manner and activates PKG. CSE deficiency blocks NO-stimulated cGMP formation, whereas eNOS deficiency or inhibition by l-NAME blocks the effect of H2S to increase cGMP levels. These studies clearly indicate a mutual requirement of H2S and NO in vascular smooth muscle relaxation. While NO enhances cGMP synthesis by activating sGC activity, H2S increases cGMP synthesis via stimulation of eNOS. Activation of eNOS by H2S was mediated via an increase in the stimulation of phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177. Phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 was markedly reduced in the hearts of CSE knockout mice (22). NO, in turn, was shown to activate CSE and generate H2S. Rat aortic tissue homogenates incubated with a NO donor for 90 min showed a significant increase in H2S generation (52). These studies suggested that NO-dependent increase in H2S generation could be due to direct activation of CSE by NO via S-nitrosylation or due to stimulation of CSE by NO/sGC/cGMP pathway. These studies also showed that incubation of vascular smooth muscle cells with NO donor for 6 h significantly increased the expression of CSE (52).

CSE and CBS are reported to be localized in different regions of the GI tract, stomach, small intestine and colon, and in different cell types, enteric neurons, ICCs, and smooth muscles (20, 27–30, 41, 43). Several studies have shown the endogenous generation of H2S in the GI tract supporting a role for H2S in the regulation of GI functions (13, 16, 28, 30). Although the expression of CSE and CBS, and physiological function of H2S in the GI tract, has been studied by several research groups, the endogenous regulation of H2S production by H2S-synthesizing enzyme CSE and the mechanism of activation are still unclear. Our studies provide evidence for the synthesis of H2S in smooth muscle from the colon of rabbit by the CSE activator l-cysteine as well as by NO donor, GSNO. The evidence was based on direct measurement of H2S production in response to l-cysteine and GSNO, and use of a specific inhibitor of CSE, dl-PPG and an inhibitor of PKG, Rp-8-Br-cGMPS. l-cysteine and GSNO-induced increase in H2S production was blocked by dl-PPG, demonstrating that activation of CSE is involved in the synthesis of H2S in response to NO. A selective PKG inhibitor blocked the effect of GSNO, suggesting the involvement of PKG in the activation of CSE. The physiological relevance of the CSE/H2S pathway activated by NO was evident from the partial inhibition of GSNO-mediated relaxation by dl-PPG in both muscle strips and isolated muscle cells. This physiological mode of cooperative action between NO and H2S is analogous to the cooperation of NO signaling and pharmacological inhibitors of PDE5 such as sildenafil.

The present study, using intact colonic segments, also suggested that H2S stimulates colonic transit. We have previously shown that CGRP is a marker of enteric sensory neuron activation, which leads to initiation of the peristaltic reflex and peristalsis (21). Here, we show that addition of l-cysteine to the sensory compartment of colonic flat sheet preparation augmented CGRP release in response to mucosal stroking, and this was partially reduced by dl-PPG. We show that in ex vivo colonic preparations, l-cysteine increased the velocity of pellet propulsion. Enhanced propulsion could also be partly due to an augmentation of the descending relaxation component of the peristaltic reflex by the direct interaction of NO and H2S at the level of the smooth muscle cell since we have previously shown that descending relaxation is mediated by NO (21).

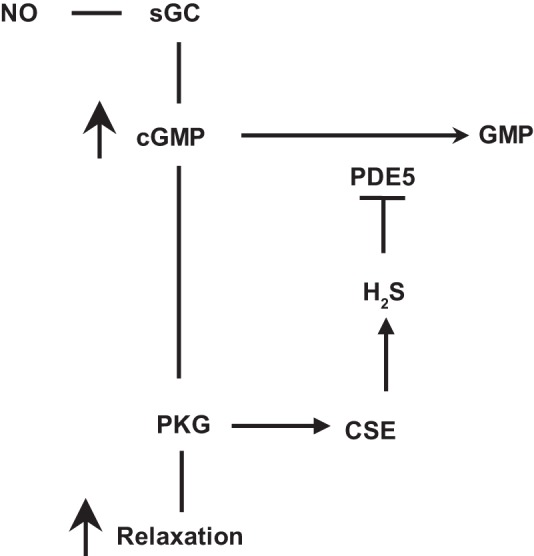

In conclusion, our studies provide evidence for the interplay between NO and H2S in colonic smooth muscle to augment each other’s effect. NO contributes to the generation of H2S via cGMP/PKG pathway, and H2S, in turn, inhibits PDE5 activity and augments NO-induced cGMP levels (Fig. 11). Thus H2S promotes NO function, and its own synthesis, via cGMP/PKG pathway. Our study also suggests that H2S stimulates colonic transit. These current findings may lead to novel approaches that focus on the simultaneous restoration of NO and H2S homeostasis in the GI smooth muscle cells and have implications for the involvement of CSE/H2S system in motility disorders and modulation of this system in therapeutics.

Fig. 11.

The interplay between NO and H2S in colonic smooth muscle. In colonic smooth muscle, relaxation in response to nitric oxide (NO) is mediated via stimulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) activity, cGMP generation, and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) activity. PKG phosphorylates various targets in the contractile pathway to decrease intracellular Ca2+ and/or increase myosin light chain phosphatase activity, key requirements in muscle relaxation. cGMP/PKG pathway, in addition, activates cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) to generate H2S, which in turn inhibits PDE5 activity and augments cGMP/PKG pathway.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-28300 and DK-15564 (to K. Murthy) and DK-34153 (to J. Grider).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.D.N., H.W., J.R.G., and K.S.M. conceived and designed research; A.D.N., S.B., H.W., J.R.G., and K.S.M. analyzed data; A.D.N., J.R.G., and K.S.M. interpreted results of experiments; A.D.N., J.R.G., and K.S.M. prepared figures; A.D.N., J.R.G., and K.S.M. drafted manuscript; A.D.N., S.B., J.R.G., and K.S.M. edited and revised manuscript; A.D.N., S.B., H.W., D.M.K., J.R.G., and K.S.M. approved final version of manuscript; S.B., H.W., D.M.K., J.R.G., and K.S.M. performed experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci 16: 1066–1071, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali MY, Ping CY, Mok YY, Ling L, Whiteman M, Bhatia M, Moore PK. Regulation of vascular nitric oxide in vitro and in vivo; a new role for endogenous hydrogen sulphide? Br J Pharmacol 149: 625–634, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beavo JA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: functional implications of multiple isoforms. Physiol Rev 75: 725–748, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bucci M, Papapetropoulos A, Vellecco V, Zhou Z, Zaid A, Giannogonas P, Cantalupo A, Dhayade S, Karalis KP, Wang R, Feil R, Cirino G. cGMP-dependent protein kinase contributes to hydrogen sulfide-stimulated vasorelaxation. PLoS One 7: e53319, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bucci M, Papapetropoulos A, Vellecco V, Zhou Z, Pyriochou A, Roussos C, Roviezzo F, Brancaleone V, Cirino G. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous inhibitor of phosphodiesterase activity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 1998–2004, 2010. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.209783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cirino G, Vellecco V, Bucci M. Nitric oxide and hydrogen sulfide: the gasotransmitter paradigm of the vascular system. Br J Pharmacol, 2017. doi: 10.1111/bph.13815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coletta C, Papapetropoulos A, Erdelyi K, Olah G, Módis K, Panopoulos P, Asimakopoulou A, Gerö D, Sharina I, Martin E, Szabo C. Hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide are mutually dependent in the regulation of angiogenesis and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 9161–9166, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202916109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhaese I, Lefebvre RA. Myosin light chain phosphatase activation is involved in the hydrogen sulfide-induced relaxation in mouse gastric fundus. Eur J Pharmacol 606: 180–186, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhaese I, Van Colen I, Lefebvre RA. Mechanisms of action of hydrogen sulfide in relaxation of mouse distal colonic smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol 628: 179–186, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis SH, Blount MA, Corbin JD. Mammalian cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular mechanisms and physiological functions. Physiol Rev 91: 651–690, 2011. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gade AR, Kang M, Akbarali HI. Hydrogen sulfide as an allosteric modulator of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in colonic inflammation. Mol Pharmacol 83: 294–306, 2013. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.081596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallego D, Clavé P, Donovan J, Rahmati R, Grundy D, Jiménez M, Beyak MJ. The gaseous mediator, hydrogen sulphide, inhibits in vitro motor patterns in the human, rat and mouse colon and jejunum. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20: 1306–1316, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gil V, Gallego D, Jiménez M. Effects of inhibitors of hydrogen sulphide synthesis on rat colonic motility. Br J Pharmacol 164, 2b: 485–498, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geng B, Cui Y, Zhao J, Yu F, Zhu Y, Xu G, Zhang Z, Tang C, Du J. Hydrogen sulfide downregulates the aortic l-arginine/nitric oxide pathway in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R1608–R1618, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00207.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han Y, Huang X, Guo X, Wu Y, Liu D, Lu H, Kim Y, Xu W. Evidence that endogenous hydrogen sulfide exerts an excitatory effect on gastric motility in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 673: 85–89, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosoki R, Matsuki N, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous smooth muscle relaxant in synergy with nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 237: 527–531, 1997. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurst NR, Kendig DM, Murthy KS, Grider JR. The short chain fatty acids, butyrate and propionate, have differential effects on the motility of the guinea pig colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil 26: 1586–1596, 2014. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeong SO, Pae HO, Oh GS, Jeong GS, Lee BS, Lee S, Kim Y, Rhew HY, Lee KM, Chung HT. Hydrogen sulfide potentiates interleukin-1β-induced nitric oxide production via enhancement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 345: 938–944, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang M, Hashimoto A, Gade A, Akbarali HI. Interaction between hydrogen sulfide-induced sulfhydration and tyrosine nitration in the KATP channel complex. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 308: G532–G539, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00281.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasparek MS, Linden DR, Farrugia G, Sarr MG. Hydrogen sulfide modulates contractile function in rat jejunum. J Surg Res 175: 234–242, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kendig DM, Hurst NR, Bradley ZL, Mahavadi S, Kuemmerle JF, Lyall V, DeSimone J, Murthy KS, Grider JR. Activation of the umami taste receptor (T1R1/T1R3) initiates the peristaltic reflex and pellet propulsion in the distal colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 307: G1100–G1107, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00251.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King AL, Polhemus DJ, Bhushan S, Otsuka H, Kondo K, Nicholson CK, Bradley JM, Islam KN, Calvert JW, Tao YX, Dugas TR, Kelley EE, Elrod JW, Huang PL, Wang R, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide cytoprotective signaling is endothelial nitric oxide synthase-nitric oxide dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 3182–3187, 2014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321871111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komalavilas P, Lincoln TM. Phosphorylation of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase mediates cAMP and cGMP dependent phosphorylation in the intact rat aorta. J Biol Chem 271: 21933–21938, 1996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubo S, Doe I, Kurokawa Y, Nishikawa H, Kawabata A. Direct inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by hydrogen sulfide: contribution to dual modulation of vascular tension. Toxicology 232: 138–146, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kubo S, Kurokawa Y, Doe I, Masuko T, Sekiguchi F, Kawabata A. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits activity of three isoforms of recombinant nitric oxide synthase. Toxicology 241: 92–97, 2007b. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Liu XJ, Furchgott RF. Blockade of nitric oxide-induced relaxation of rabbit aorta by cysteine and homocysteine. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao 18: 11–20, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linden DR. Hydrogen sulfide signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 818–830, 2014. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linden DR, Sha L, Mazzone A, Stoltz GJ, Bernard CE, Furne JK, Levitt MD, Farrugia G, Szurszewski JH. Production of the gaseous signal molecule hydrogen sulfide in mouse tissues. J Neurochem 106: 1577–1585, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linden DR, Levitt MD, Farrugia G, Szurszewski JH. Endogenous production of H2S in the gastrointestinal tract: still in search of a physiologic function. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1135–1146, 2010. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin GR, McKnight GW, Dicay MS, Coffin CS, Ferraz JG, Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulphide synthesis in the rat and mouse gastrointestinal tract. Dig Liver Dis 42: 103–109, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Cutillas M, Gil V, Mañé N, Clavé P, Gallego D, Martin MT, Jimenez M. Potential role of the gaseous mediator hydrogen sulphide (H2S) in inhibition of human colonic contractility. Pharm Res 93: 52–63, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murthy KS. Signaling for contraction and relaxation in smooth muscle of the gut. Annu Rev Physiol 68: 345–374, 2006. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040504.094707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murthy KS. Activation of phosphodiesterase 5 and inhibition of guanylate cyclase by cGMP-dependent protein kinase in smooth muscle. Biochem J 360: 199–208, 2001. doi: 10.1042/bj3600199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murthy KS, Zhou H. Selective phosphorylation of the IP3R-I in vivo by cGMP-dependent protein kinase in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284: G221–G230, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00401.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nalli AD, Rajagopal S, Mahavadi S, Grider JR, Murthy KS. Inhibition of RhoA-dependent pathway and contraction by endogenous hydrogen sulfide in rabbit gastric smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 308: C485–C495, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00280.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagao M, Linden DR, Duenes JA, Sarr MG. Mechanisms of action of the gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide in modulating contractile activity of longitudinal muscle of rat ileum. J Gastrointest Surg 15: 12–22, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagao M, Duenes JA, Sarr MG. Role of hydrogen sulfide as a gasotransmitter in modulating contractile activity of circular muscle of rat jejunum. J Gastrointest Surg 16: 334–343, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1734-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ny L, Pfeifer A, Aszòdi A, Ahmad M, Alm P, Hedlund P, Fässler R, Andersson KE. Impaired relaxation of stomach smooth muscle in mice lacking cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase I. Br J Pharmacol 129: 395–401, 2000. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parajuli SP, Choi S, Lee J, Kim YD, Park CG, Kim MY, Kim HI, Yeum CH, Jun JY. The inhibitory effects of hydrogen sulfide on pacemaker activity of interstitial cells of Cajal from mouse small intestine. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 14: 83–89, 2010. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2010.14.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qu K, Chen CP, Halliwell B, Moore PK, Wong PT. Hydrogen sulfide is a mediator of cerebral ischemic damage. Stroke 37: 889–893, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000204184.34946.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quan X, Luo H, Liu Y, Xia H, Chen W, Tang Q. Hydrogen sulphide regulates the colonic motility by inhibiting both L-type calcium channels and BKCa channels in smooth muscle cells of the rat colon. PLoS One 10: e121331, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rattan S, Singh J. Basal internal anal sphincter tone, inhibitory neurotransmission, and other factors contributing to the maintenance of high pressures in the anal canal. Neurogastroenterol Motil 23: 3–7, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schicho R, Krueger D, Zeller F, Von Weyhern CWH, Frieling T, Kimura H, Ishii I, De Giorgio R, Campi B, Schemann M. Hydrogen sulfide is a novel prosecretory neuromodulator in the Guinea-pig and human colon. Gastroenterology 131: 1542–1552, 2006. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sha L, Linden DR, Farrugia G, Szurszewski JH. Effect of endogenous hydrogen sulfide on the transwall gradient of the mouse colon circular smooth muscle. J Physiol 592: 1077–1089, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.266841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strege PR, Bernard CE, Kraichely RE, Mazzone A, Sha L, Beyder A, Gibbons SJ, Linden DR, Kendrick ML, Sarr MG, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. Hydrogen sulfide is a partially redox-independent activator of the human jejunum Na+ channel, Nav1.5. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300: G1105–G1114, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00556.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szabo C. Hydrogen sulfide, an enhancer of vascular nitric oxide signaling: mechanisms and implications. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 312: C3–C15, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00282.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szabó C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6: 917–935, 2007. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teague B, Asiedu S, Moore PK. The smooth muscle relaxant effect of hydrogen sulphide in vitro: evidence for a physiological role to control intestinal contractility. Br J Pharmacol 137: 139–145, 2002. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol Rev 92: 791–896, 2012. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whiteman M, Li L, Kostetski I, Chu SH, Siau JL, Bhatia M, Moore PK. Evidence for the formation of a novel nitrosothiol from the gaseous mediators nitric oxide and hydrogen sulphide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 343: 303–310, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyatt TA, Naftilan AJ, Francis SH, Corbin JD. ANF elicits phosphorylation of the cGMP phosphodiesterase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Lung Physiol 274: H448–H455, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao W, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang R. The vasorelaxant effect of H2S as a novel endogenous gaseous KATP channel opener. EMBO J 20: 6008–6016, 2001. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao P, Huang X, Wang ZY, Qiu ZX, Han YF, Lu HL, Kim YC, Xu WX. Dual effect of exogenous hydrogen sulfide on the spontaneous contraction of gastric smooth muscle in guinea-pig. Eur J Pharmacol 616: 223–228, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]