A new methodology has been developed to measure O2 consumption rates in engineered cardiac tissues with independent control over tissue alignment and matrix elasticity. This led to the findings that matrix elasticity regulates basal mitochondrial function, whereas both matrix elasticity and tissue alignment regulate mitochondrial stress responses.

Keywords: cardiac myocytes, mitochondria, extracellular matrix, mechanotransduction, microfabrication

Abstract

Mitochondria in cardiac myocytes are critical for generating ATP to meet the high metabolic demands associated with sarcomere shortening. Distinct remodeling of mitochondrial structure and function occur in cardiac myocytes in both developmental and pathological settings. However, the factors that underlie these changes are poorly understood. Because remodeling of tissue architecture and extracellular matrix (ECM) elasticity are also hallmarks of ventricular development and disease, we hypothesize that these environmental factors regulate mitochondrial function in cardiac myocytes. To test this, we developed a new procedure to transfer tunable polydimethylsiloxane disks microcontact-printed with fibronectin into cell culture microplates. We cultured Sprague-Dawley neonatal rat ventricular myocytes within the wells, which consistently formed tissues following the printed fibronectin, and measured oxygen consumption rate using a Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer. Our data indicate that parameters associated with baseline metabolism are predominantly regulated by ECM elasticity, whereas the ability of tissues to adapt to metabolic stress is regulated by both ECM elasticity and tissue alignment. Furthermore, bioenergetic health index, which reflects both the positive and negative aspects of oxygen consumption, was highest in aligned tissues on the most rigid substrate, suggesting that overall mitochondrial function is regulated by both ECM elasticity and tissue alignment. Our results demonstrate that mitochondrial function is regulated by both ECM elasticity and myofibril architecture in cardiac myocytes. This provides novel insight into how extracellular cues impact mitochondrial function in the context of cardiac development and disease.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY A new methodology has been developed to measure O2 consumption rates in engineered cardiac tissues with independent control over tissue alignment and matrix elasticity. This led to the findings that matrix elasticity regulates basal mitochondrial function, whereas both matrix elasticity and tissue alignment regulate mitochondrial stress responses.

because of the significant amount of energy required for sarcomere shortening, mitochondria are especially prevalent in cardiac myocytes, occupying ~35% of cell volume (15, 25). Mitochondria in cardiac myocytes remodel both structurally and functionally throughout development, health, and disease (2, 3, 23). For example, neonatal rat and mouse cardiac myocytes are mostly glycolytic (47, 57) and mitochondria are randomly distributed throughout the cell (5, 34). As cardiac myocytes mature, mitochondria become highly organized and associate closely with sarcomeres (5, 34), which mature on a similar timescale. During this time, myocytes also become more reliant on oxidative phosphorylation instead of glycolysis (23, 39, 47, 57, 59). Similarly, as human embryonic stem cells differentiate into cardiac myocytes in vitro, mitochondria become more organized, and metabolism switches from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation (13, 14). Mitochondria and metabolism in cardiac myocytes also remodel in many pathological settings. For example, healthy cardiac myocytes rely primarily on fatty acids, but, in ischemic heart disease, myocytes switch to glucose (36, 50). Similarly, fatty acid oxidation decreases in rodent models of pressure-overload hypertrophy, leading to impaired mitochondrial function (9, 16). Thus metabolic remodeling is a key component of many physiological and pathological processes in cardiac myocytes, although the factors driving metabolic remodeling are not completely understood.

Cardiac development and disease are also associated with diverse changes in the cardiac myocyte microenvironment (44). During development, cardiac myocytes gradually elongate and self-assemble into an aligned tissue (31). Concurrently, the elastic modulus of the extracellular matrix (ECM), and, therefore, the load on cardiac myocytes, also increases (20, 40). Many cardiac diseases are associated with fibrosis, which further increases the elastic modulus of the tissue (7) and can lead to disruption of tissue alignment (41). Several in vitro studies have demonstrated that remodeling of tissue architecture and the elasticity of the ECM impact the electrical and contractile function of cardiac myocytes. For example, engineered cardiac tissues aligned by microcontact printing generate higher contractile stresses, propagate action potentials more rapidly, and have more mature calcium transients compared with unaligned tissues (10, 21, 27, 37, 45). Furthermore, both myocyte shape and ECM elasticity affect contractility and sarcomere formation (20, 40, 43, 46). However, few studies have investigated relationships between the tissue microenvironment and metabolism in cardiac myocytes. Previously, we showed that cardiac myocytes cultured uniformly on gelatin hydrogels have higher spare respiratory capacity compared with those cultured uniformly on fibronectin-coated polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (42), suggesting potential links between the ECM and mitochondrial function. However, due to the multiple differences between gelatin hydrogels and fibronectin-coated PDMS, this study provides limited insight into which microenvironmental factors regulate mitochondrial function in cardiac myocytes. This study also did not include tissue alignment as a variable, which is likely important due to the tight spatial relationship between sarcomeres and mitochondria (5, 34). Thus relationships between the cardiac myocyte microenvironment and metabolism are still mostly unknown.

Our goal for this study was to test the hypothesis that ECM elasticity and tissue architecture impact mitochondrial function in cardiac myocytes. Mitochondrial function is commonly characterized by measuring oxygen consumption rate (OCR) with a Seahorse Bioscience extracellular flux analyzer. However, this device requires cells to be cultured within specialized XF24 cell culture microplates, which poses a significant obstacle for modifying ECM elasticity and tissue alignment. To overcome this limitation, we developed a technique for transferring PDMS disks with tunable elasticity and micropatterned with fibronectin into the bottom of XF24 cell culture microplates. We then cultured neonatal rat cardiac myocytes within the wells, validated tissue structure and alignment, and performed mitochondrial respirometry experiments. Our results suggest that select mitochondrial functions are regulated solely by ECM elasticity, while others are regulated by both ECM elasticity and tissue alignment. These results provide new insights into links between mitochondrial function, ECM elasticity, and tissue architecture in cardiac myocytes, which has many implications for understanding how extracellular and intracellular structures are coordinated during cardiac development and disease. Additionally, our engineered platform enables a variety of new studies into mechanisms associated with the regulation of metabolism by the ECM in other cell and tissue systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fabrication of mechanically tunable PDMS.

Three types of PDMS with distinct elastic moduli were prepared using Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer and Sylgard 527 silicone dielectric gel (Dow Corning). Sylgard 184 was prepared by mixing a 1:10 mass ratio of elastomer curing agent to base. Sylgard 527 was prepared by mixing A and B components in a 1:1 mass ratio. An intermediate PDMS was prepared by mixing Sylgard 184 with Sylgard 527 in a 1:20 mass ratio, similar to previous studies (8, 51). All polymers were mixed for 2 min and degassed for 2 min using a planetary centrifugal mixer (Thinky AR-100 Conditioning Mixer).

Bulk compressive elastic modulus measurements.

Sylgard 184 and the 1:20 mixture of Sylgard 184 and Sylgard 527 were prepared as described above, poured into petri dishes, and cured at 65°C overnight. Cylinders of 6-mm diameter were then cut and removed using a biopsy punch. To fabricate cylinders of Sylgard 527, 1.7-ml centrifuge tubes were coated with poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm) dissolved in butanol at 10% wt/vol. Next, Sylgard 527 was prepared as described above, poured into PNIPAm-coated tubes, and cured at 65°C overnight. Tubes were then incubated in room temperature water to liquefy the PNIPAm and release the PDMS, which was cut into cylinders using a razor blade.

For each type of PDMS, cylinders were mounted on an Instron 5942 Mechanical Testing System. Each cylinder was compressed 40% of its initial height. The 1–4% range of compressive strain was used for elastic modulus calculations, taking into account the height and radius of each cylinder. For each type of PDMS, at least four independent batches of PDMS were fabricated and measured in triplicate.

Master wafer and PDMS stamp fabrication.

Standard photolithography and soft lithography techniques (10, 45, 52) were used to fabricate master wafers and PDMS stamps. Briefly, to fabricate wafers for aligned stamps, silicon wafers were cleaned using a nitrogen gun, spin-coated with a layer of hexamethyldisilazane, spin-coated with a 2-µm-thick layer of the negative photoresist SU-8 2002 (MicroChem), and baked according to manufacturer instructions. Next, a photolithographic mask with 15-µm-wide lines separated by 2 µm (referred to as 15 × 2) was positioned over the wafer using a standard mask aligner (Karl-Suss MJB3 Contact Aligner). The masked wafer was then exposed to high-energy UV light, baked, and immersed in developer solution to remove unexposed photoresist. The wafer was then silanized by incubating it with a drop of trichloro(1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluorooctyl)silane overnight in a vacuum desiccator. To fabricate featureless wafers for isotropic stamps, virgin silicon wafers were silanized. Sylgard 184 PDMS was prepared as described above, poured over master wafers in 150 mm petri dishes, polymerized at 65°C overnight, and peeled off the wafer. Cured PDMS was removed from the wafer, and individual PDMS stamps measuring ~2 cm × 2 cm were then cut.

Fabrication of micropatterned PDMS disks.

To fabricate PDMS disks, we adapted previously published protocols for fabricating PDMS muscular thin films (21, 43). Briefly, PNIPAm was dissolved in butanol at 10% wt/vol and spin-coated onto 22-mm-square coverslips using a Specialty Coating Systems G3P-8 spin coater. Next, coverslips were spin-coated with a layer of PDMS Sylgard 184 and incubated at 65°C for at least 4 h. Select constructs were then spin-coated with a layer of Sylgard 527 or the 1:20 blend of Sylgard 184 and Sylgard 527. These constructs were then cured again at 65°C for at least 4 h. Next, an Epilog Mini 24 Laser Engraver (30 W) was used to etch nine circular disks with 6.5-mm diameter into each construct (power: 4, speed: 10, frequency: 300).

PDMS stamps (aligned or isotropic) were sonicated in 95% ethanol and dried using compressed air in a sterilized biosafety cabinet. Human fibronectin in distilled, deionized water (50 µg/ml) was pipetted onto the surface of each stamp and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. PDMS-coated, laser-engraved coverslips were treated in a UVO cleaner model 342 (Jelight) for 8 min to sterilize and oxidize the surface. Stamps were then blown dry under compressed air, placed gently onto treated coverslips to transfer the fibronectin, and carefully removed. XF24 cell culture microplates were treated in a plasma cleaner (Harrick Plasma) at high power for 10 min and transferred to the biosafety cabinet. Micropatterned PDMS disks were then carefully peeled from the glass coverslip using tweezers and transferred to the bottoms of the microplate wells. Pressure was applied to remove any bubbles trapped between the disks and the microplate, especially near the edges. The plates were then rinsed in sterile PBS and stored at 4°C until cell seeding.

Neonatal rat ventricular myocyte harvest and culture.

Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes were isolated from 2-day-old neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats, similar to previously published protocols. Harvest procedures were approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, ventricles were extracted from rat pups and incubated in Trypsin solution (1 mg/ml, Affymetrix) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution overnight at 4°C. Ventricles were then subjected to four collagenase [1 mg/ml (Worthington Biochemical) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution] digestions for 1–2 min each at 37°C, followed by manual pipette agitation. Cells were then strained, resuspended in M199 culture medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM MEM nonessential amino acids, 20 mM glucose, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1.5 µM vitamin B-12, and 50 U/ml penicillin. The cells were preplated twice for 45 min each to minimize fibroblast contamination.

For mitochondrial respirometry studies, 50,000 cells·50 µl−1·well−1 were seeded in each well of the XF24 cell culture microplates containing the micropatterned disks. After seeding was completed, plates were left in the biosafety cabinet for 30 min to prevent cell aggregation at the well’s edges, as suggested by the manufacturer. Plates were then placed in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. After 1–4 h, an additional 450 µl of media were added to each well. For all wells, FBS concentration in the media was reduced to 2% after 2 days in culture, and media was exchanged every other day.

Immunostaining.

Tissues within XF24 cell culture microplates were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 solution for 10 min. Fixed tissues or micropatterned coverslips (without cells) were incubated with monoclonal mouse anti-sarcomeric α-actinin (1:1,000, Sigma) or monoclonal rabbit anti-fibronectin (1:200, Sigma) primary antibodies, respectively, for 1 h at room temperature. After being rinsed with PBS, samples were incubated with chemical stains 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:1,000) and Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin (1:1,000, Life Technologies), and either Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1,000, Life Technologies) or Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200, Life Technologies), for 1 h at room temperature. Tissues were then coated with a drop of ProLong Gold Anti-Fade Mountant, sealed with Parafilm, and stored at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted on a glass slide with ProLong Gold Anti-Fade Mountant and sealed with nail polish.

Microscopy and image analysis.

For each XF24 cell culture microplate, confocal images of at least five locations dispersed across each well were collected using a ×20 air objective (with ×2 digital zoom to a total magnification of ×40) on a Nikon C2 point-scanning confocal microscope system. With the use of ImageJ, the total number of nuclei per field of view (based on 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole stain) was counted. Actin fiber alignment was computed using a software based on fingerprint detection algorithms, as previously described (1, 21, 27, 45). The orientational order parameter, which varies from zero for completely isotropic systems to one for completely aligned systems, was calculated from the actin fiber alignment data (27).

Mitochondrial respirometry.

Cellular metabolism was measured using a Seahorse Bioscience XFe24 extracellular flux analyzer, as previously described (42, 56). After 5 days in culture, cell media was replaced with XF Assay Medium (Seahorse Bioscience) supplemented with 10 mM glucose, 2 µM l-glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (pH 7.4), and the plate was incubated for 1 h in a 37°C, non-CO2 incubator. The wells of a hydrated sensor cartridge were then loaded with 2 µM oligomycin (port A), 1 µM FCCP (port B), and a mixture of 1 µM antimycin A and 1 µM rotenone (port C), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A standard mitochondrial stress test was then conducted. Mitochondria-related ATP production was calculated by subtracting the OCR after oligomycin injection from the baseline OCR. Spare respiratory capacity was calculated by subtracting the baseline OCR from the OCR after FCCP injection. Nonmitochondrial respiration was determined from the OCR value after antimycin/rotenone injection. Lastly, basal respiration was determined by subtracting the OCR after antimycin/rotenone injection from the OCR at baseline. For each well, the OCR measurements were normalized to total protein content, determined with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific), as described below. In addition, the bioenergetic health index (BHI) was calculated using the normalized OCR values obtained from mitochondrial respirometry using the following formula (11):

Measurements of protein concentration.

After OCR measurements, wells were rinsed twice with PBS, and 100 µl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and 400 µl of PBS were added to each well. Cell lysates were transferred to 1.7-ml centrifuge tubes and stored at −20°C. BCA protein assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 parts of BCA reagent A and 1 part of BCA reagent B were mixed in a conical tube to obtain the working reagent. Two hundred microliters of working reagent were added to the wells of a 96-well plate, followed by cell lysates at a ratio of 1:8 samples or standards to working reagent. After 1-h incubation at 37°C, absorbance was read using a plate reader (Varioskan Lux, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and values were fit to a protein standard curve (using BSA) to calculate protein concentrations. Total protein mass per well was computed by multiplying the protein concentration by the total volume of the lysate (500 µl).

Statistical analysis.

Normality for all measurements was first validated using the Lilliefors test. Elastic moduli data were analyzed using Student’s t-test, with α set to 0.05. The remaining data were analyzed using one-way and/or two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons in MATLAB, with α set to 0.05. Each biological parameter was tested in at least three independent harvests, and multiple wells per harvest per condition were used in the analysis.

RESULTS

Tuning tissue alignment and ECM elasticity within XF24 cell culture microplates.

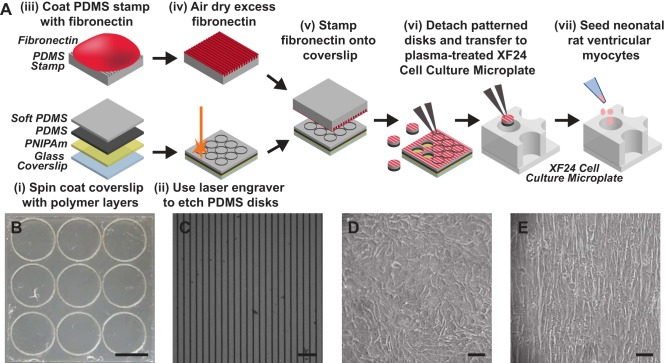

In ventricular myocardium, dynamic remodeling of tissue architecture and ECM elasticity occur in both cardiac development and disease (44). We hypothesized that both microenvironmental factors impact the function of mitochondria in cardiac myocytes. To test this hypothesis in vitro, we utilized the Seahorse XFe24 extracellular flux analyzer, which measures OCR of cells cultured in XF24 cell culture microplates as an indicator of mitochondrial respiration. However, many conventional techniques for engineering properties of the ECM for cell culture, such as microcontact printing, are incompatible with these microplates due to the physical restrictions of the wells. To overcome this, we developed a technique to engineer ECM surfaces outside of the microplate and transfer them into the wells as the final step before cell seeding. As shown in Fig. 1A, we first spin-coated 22-mm-square glass coverslips with PNIPAm, followed by Sylgard 184 PDMS. After curing the PDMS, we laser-engraved the coated coverslips with 6.5-mm-diameter circles (Fig. 1B), which is just slightly larger than the wells of the XF24 cell culture microplates (diameter: 6.3 mm). Because of a slight loss of material during the etching process, the final disks were 6.35–6.4 mm in diameter. Using disks slightly larger than the bottom of the wells was advantageous because the wells have three pillars that restrict the disk from laying perfectly flat. Furthermore, disks would attach slightly to the walls of the wells, guaranteeing full coverage of the bottom of the well with the disk and minimizing the dislodgement of disks during rinses and media changes. Next, we used microcontact printing to transfer either uniform or 15 × 2 lines of fibronectin (Fig. 1C) to the laser-engraved coverslips. We then used tweezers to detach micropatterned disks from the coverslips, which released easily due to the PNIPAm layer, and transferred them to the wells of XF24 cell culture microplates treated in a plasma oxidizer. Next, we seeded neonatal rat ventricular myocytes into wells containing PDMS disks. Myocytes seeded in wells with uniform fibronectin formed isotropic tissues (Fig. 1D), whereas myocytes in wells with 15 × 2 fibronectin formed aligned tissues (Fig. 1E). Thus we successfully engineered isotropic and aligned neonatal rat ventricular myocyte tissues within the wells of XF24 cell culture microplates.

Fig. 1.

Engineering cardiac tissues within XF24 cell culture microplates. A: glass coverslips were spin-coated with layers of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm) and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (i), laser-engraved into disks (ii), and microcontact printed (iii–v) with fibronectin. Micropatterned disks were then detached from the coverslip, transferred into a XF24 cell culture microplate (vi), and seeded with neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (vii). B: laser-engraved PDMS disks on a square glass coverslip (22 mm × 22 mm) obtained after step ii in A. Scale bar: 5 mm. C: immunostained 15 × 2 fibronectin on a micropatterned PDMS disk obtained after step v in A. Scale bar: 50 µm. Isotropic cardiac tissue on PDMS disk patterned with uniform fibronectin (D), and aligned cardiac tissue on PDMS disk patterned with 15 × 2 fibronectin (E) are shown. Scale bars: 50 µm.

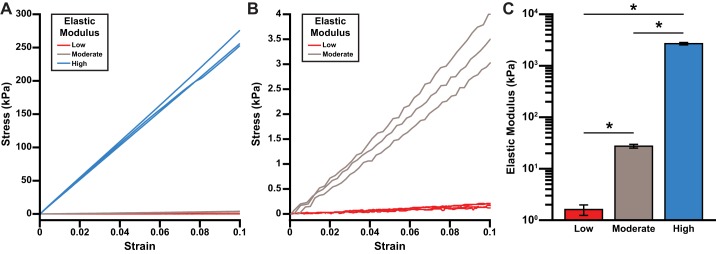

To tune the elasticity of the ECM within the XF24 cell culture microplate, we next fabricated three formulations of PDMS with distinct elastic moduli: pure Sylgard 184, pure Sylgard 527, and a 1:20 blend of Sylgard 184/Sylgard 527, similar to previous studies (8, 51). Representative stress-strain curves for these three formulations (Fig. 2, A and B) demonstrate that each is approximately linearly elastic under the range of strain 1–4%. As shown in Fig. 2C, the average elastic modulus of pure Sylgard 527 was measured as 1.61 ± 0.37 kPa (mean ± SE, n = 4), similar to ex vivo passive measurements of developing myocardium (20, 40). The elastic modulus of blended PDMS was measured as 27.4 ± 2.3 kPa (mean ± SE, n = 5), similar to ex vivo passive measurements of adult myocardium (20, 40). Finally, the elastic modulus of pure Sylgard 184 was measured as 2,686.7 ± 143.6 kPa (mean ± SE, n = 7), which is supraphysiological, but may recapitulate the high mechanical load applied to cardiac myocytes in pathological situations, such as pressure overload (7). To simplify our terminology, we will subsequently refer to pure Sylgard 527 as low, 1:20 Sylgard 184/Sylgard 527 as moderate, and pure Sylgard 184 as high.

Fig. 2.

Elastic moduli of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) formulations. A and B: stress-strain curves for the three PDMS formulations (low: pure Sylgard 527; moderate: 1:20 Sylgard 184/Sylgard 527; and high: pure Sylgard 184), with different y-axis scales. C: average elastic moduli for the three different formulations of PDMS. Values are means ± SE; n = 4 for low, n = 5 for moderate, and n = 7 for high. *P < 0.001.

To determine the impact of substrate elasticity on mitochondrial function, we followed the same procedure described above, with one additional step. After spin-coating high PDMS on PNIPAm-coated coverslips was completed, we spin-coated an additional layer of either low or moderate PDMS. The constructs were then similarly laser-engraved, microcontact-printed, and transferred to microplate wells. The high PDMS was needed as a support layer for the low and moderate PDMS to provide structural stability during the disk transfer process. With this technique, we can independently control both ECM patterning and elasticity within XF24 cell culture microplates.

Engineering isotropic and aligned cardiac tissues within XF24 cell culture microplates.

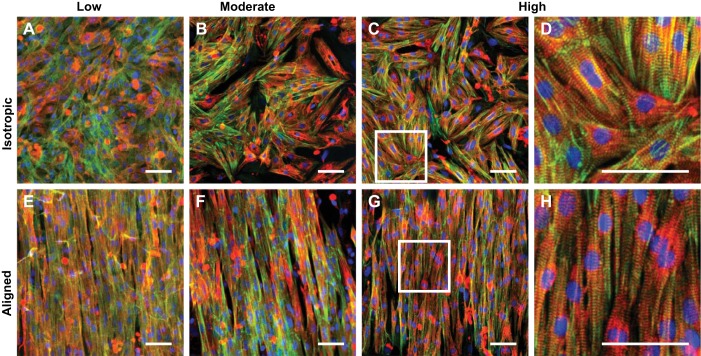

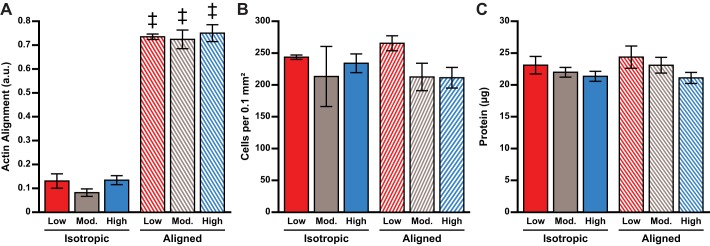

To determine the impact of ECM micropatterning and elasticity on cardiac tissue architecture, we next immunostained neonatal rat ventricular myocyte tissues cultured within the modified XF24 cell culture microplates for 5 days. As shown in Fig. 3, myocytes self-assembled into isotropic and aligned tissues as expected based on the fibronectin micropatterning, regardless of ECM elasticity. We also detected sarcomeric α-actinin-positive striations within the majority of cells for all conditions, indicating that tissues consisted primarily of cardiac myocytes with minimal fibroblast contamination. However, it was often difficult to clearly resolve individual sarcomeres because these images were collected through the bottom of the microplate, which is fabricated from thick polystyrene plastic incompatible with imaging at high magnification. To quantify tissue alignment, we measured the orientational order parameter of stained actin filaments. For each elasticity, aligned tissues had significantly higher actin alignment compared with isotropic tissues (Fig. 4A, P < 0.001 for aligned vs. isotropic, all substrates). For both isotropic and aligned tissues, actin alignment was independent of ECM elasticity, indicating the robustness of the microcontact printing process for the different PDMS formulations and the limited impact of ECM elasticity on myofibril alignment.

Fig. 3.

Cardiac tissues engineered within XF24 cell culture microplates. Composite images of neonatal rat ventricular myocyte tissues cultured on the indicated conditions are shown. A–D: isotropic tissues. E–H: aligned tissues. A and E: low. B and F: moderate. C and G: high. D and H are zoomed-in images of the white boxes in C and G, respectively. Blue: nuclei; green: actin, red: α-actinin. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Fig. 4.

Quantification of tissue architecture. Actin alignment (calculated as the orientational order parameter; n = 9 for all conditions; A), cells per 0.1 mm2 (n = 9 for all conditions; B), and total protein content per well measured using BCA assay (n = 16 for all conditions; C) are shown. a.u., Arbitrary units. Values are means ± SE. ‡P < 0.05 compared with isotropic tissues, same elasticity.

To determine whether cell density was conserved between conditions, we also counted the number of nuclei in our immunostained images. We did not detect any statistical differences in the overall number of cells (Fig. 4B) between any conditions, suggesting that cell density was similar for all conditions. We also measured total protein content and did not identify any statistical differences (Fig. 4C). Thus we engineered neonatal rat ventricular myocyte tissues within XF24 cell culture microplates with uniform density and protein content and alignment dictated by the fibronectin micropatterning. These measurements were all independent of ECM elasticity.

Coregulation of mitochondrial function by ECM elasticity and tissue alignment.

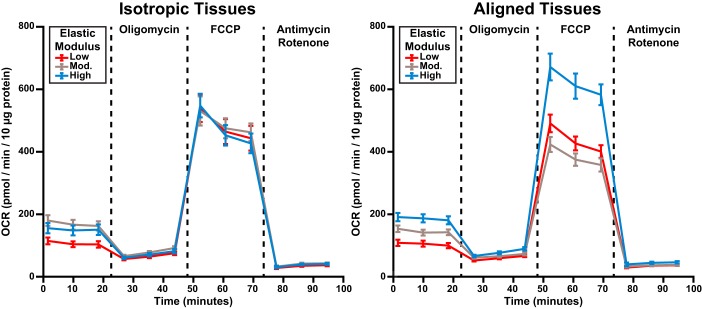

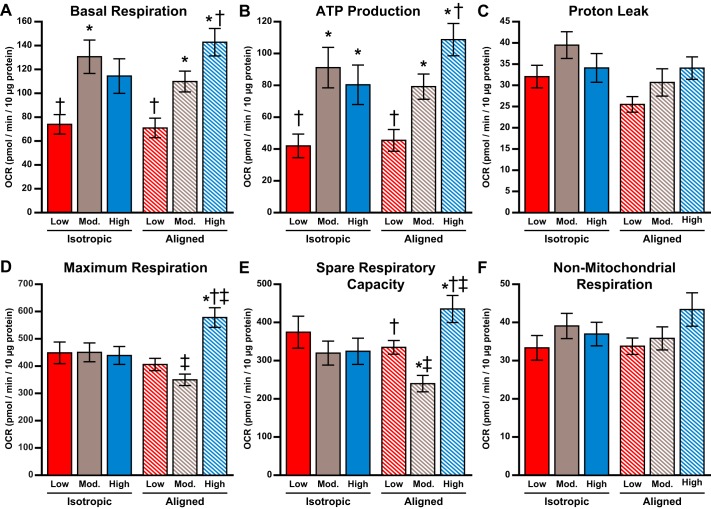

Next, we utilized a Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer to quantify OCR in cardiac tissues engineered within our modified XF24 cell culture microplates. As shown in Fig. 5, we added oligomycin, FCCP, and antimycin/rotenone in series to alter mitochondrial function, as previously described (42, 56). This assay, known as the mitochondrial stress test, allowed us to determine mitochondria-related basal respiration, ATP production, proton leak, maximum respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and nonmitochondrial respiration, as shown in Fig. 6. To determine the independent effects of tissue alignment and ECM elasticity on mitochondrial function, we first performed two-way ANOVA, followed by multiple comparisons (Table 1). These tests are used to identify the individual and combined impact of two independent variables on an outcome. Based on this analysis, basal respiration, ATP production, maximum respiration, and spare respiratory capacity were each regulated by ECM elasticity, but not tissue architecture (Fig. 6). Specifically, tissues on low substrates had lower basal respiration compared with those on moderate and high substrates (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively). Similarly, tissues on low substrates had lower ATP production compared with those on moderate and high substrates (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively). In contrast, tissues on both low and moderate substrates had lower maximum respiration compared with those on high substrates (P < 0.05 and P < 0.003, respectively), as shown in Fig. 6. As a consequence of these differences in basal and maximum respiration, tissues on moderate substrates had lower spare respiratory capacity than those on high substrates (P < 0.006). Proton leak was independent of ECM elasticity and was the only parameter regulated solely by tissue architecture, with lower values in aligned tissues (P < 0.04). The OCR associated with nonmitochondrial respiration was not regulated by ECM elasticity or tissue alignment, which is a strong indicator that the cells in each condition were similar in overall health, density, and composition (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) measurements in engineered cardiac tissues. Average experimental OCR measurements for isotropic (left) and aligned (right) tissues at baseline and after addition of oligomycin, FCCP, and antimycin and rotenone are shown. Values are means ± SE; n = 16 for all conditions.

Fig. 6.

Metabolic function in engineered cardiac tissues. Average oxygen consumption rate (OCR) associated with basal respiration (A), ATP production (B), proton leak (C), maximum respiration (D), spare respiratory capacity (E), and nonmitochondrial respiration (F) is shown. Values are means ± SE; n = 16 for all conditions. *P < 0.05 compared with tissues on low polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), same architecture. †P < 0.05 compared with tissues on moderate PDMS, same architecture. ‡P < 0.05 compared with isotropic tissues, same elasticity.

Table 1.

Two-way ANOVA for mitochondrial respirometry data

| Comparison |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Elasticity | Alignment | Interaction |

| Basal respiration | <0.0001* | 0.8702 | 0.0894 |

| ATP production | <0.0001* | 0.4125 | 0.1246 |

| Proton leak | 0.0667 | 0.0308* | 0.2886 |

| Maximum respiration | 0.0027* | 0.9150 | 0.0008* |

| Spare respiratory capacity | 0.0057* | 0.9083 | 0.0080* |

| Nonmitochondrial respiration | 0.1310 | 0.6530 | 0.3293 |

| Bioenergetic health index | 0.0001* | 0.0057* | 0.0413* |

Data for all conditions were normally distributed, as determined by the Lilliefors test. P values for each comparison are indicated.

P < 0.05.

To further delineate the impact of tissue alignment and ECM elasticity on mitochondrial function, we next performed one-way ANOVA, followed by multiple comparisons on subsets of our data, classified by either tissue alignment or ECM elasticity (Fig. 6). In isotropic tissues, basal respiration was higher only on the moderate substrate compared with the low substrate (P < 0.008), whereas ATP production was higher only for the moderate and high substrates compared with the low substrate (P < 0.009 and P < 0.05, respectively). Maximum respiration and spare respiratory capacity were not significantly different at each elastic modulus in isotropic tissues. For aligned tissues, basal respiration increased with each increase in elastic modulus (P < 0.02 for low vs. moderate, P < 0.001 for low vs. high, and P < 0.05 for moderate vs. high). Similarly, ATP production in aligned tissues increased with each increase in elastic modulus (P < 0.02 for low vs. moderate, P < 0.001 for low vs. high, and P < 0.05 for moderate vs. high). For aligned tissues, maximum respiration was higher on high substrates compared with both low and moderate substrates (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively). Likewise, spare respiratory capacity was significantly higher on high substrates compared with both low and moderate substrates (P < 0.03 and P < 0.001, respectively). Interestingly, spare respiratory capacity in aligned tissues was lowest for the moderate substrate compared with both low and high substrates (P < 0.04 and P < 0.001, respectively). Proton leak and nonmitochondrial respiration did not show statistical differences for any subset of data. Together, these data suggest that certain aspects of mitochondrial function are more sensitive to ECM elasticity in aligned tissues compared with isotropic tissues.

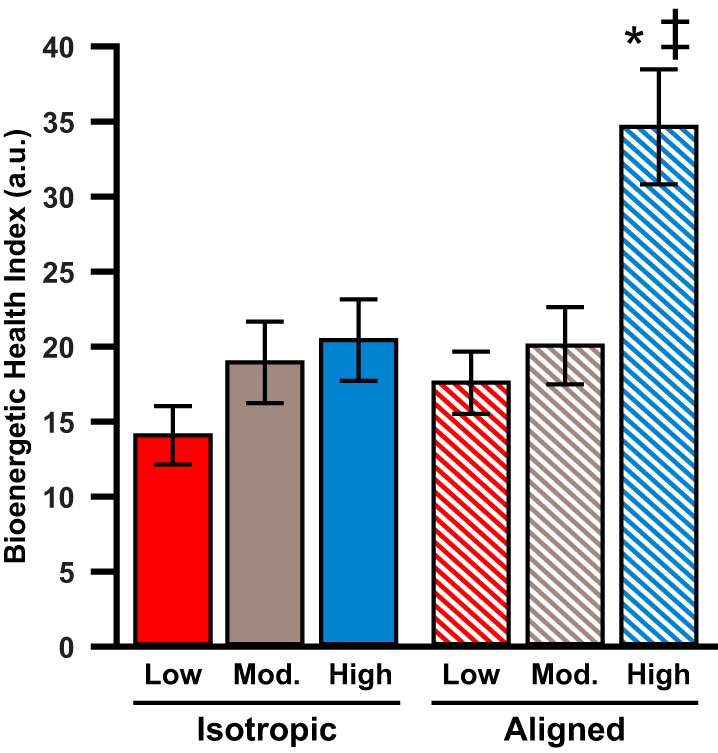

Next, we calculated the BHI of our tissues based on the OCR measurements, as shown in Fig. 7. This value reflects the combined impact of both the positive aspects of oxygen consumption (ATP production and spare respiratory capacity) and the negative aspects of oxygen consumption (proton leak and nonmitochondrial respiration) (11). Based on two-way ANOVA statistical analysis (Table 1), we observed that the BHI is regulated by both ECM elasticity and tissue architecture. Specifically, aligned tissues had higher BHI than isotropic tissues (P < 0.006), and tissues on high substrates had higher BHI than those on low and moderate substrates (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively). Based on one-way ANOVA, we identified no differences in BHI based on ECM elasticity in isotropic tissues. However, for aligned tissues, BHI was higher on high substrates compared with low and moderate substrates (P < 0.001 and P < 0.003, respectively). We also found that, on high substrates, the BHI for aligned tissues was higher than that for isotropic tissues (P < 0.006). Thus, overall, these data indicate that BHI is sensitive to both ECM elasticity and tissue alignment, as this parameter was maximized in aligned tissues on substrates with the highest elastic modulus.

Fig. 7.

Bioenergetic health index in engineered cardiac tissues. Average bioenergetic health index for all conditions is shown. Values are means ± SE; n = 16 for all conditions. *P < 0.05 compared with tissues on low polydimethylsiloxane, same architecture. ‡P < 0.05 compared with isotropic tissues, same elasticity.

DISCUSSION

Remodeling of tissue architecture, ECM elasticity, and mitochondrial function are each associated with distinct phases of cardiac development and disease, but relationships between these phenomena have not yet been clearly established. In this study, we developed a method to robustly control ECM elasticity and cardiac tissue alignment within cell culture microplates. This approach enabled us to utilize a Seahorse XFe24 extracellular flux analyzer to establish how these two variables independently and jointly impact mitochondrial function in engineered cardiac tissues. Our results suggest that different aspects of mitochondrial function are uniquely regulated by tissue architecture and/or ECM elasticity, indicating that mitochondrial function is sensitive to remodeling of the tissue microenvironment. These data are important for understanding the factors that regulate mitochondrial function during cardiac development and disease, which can help improve the differentiation of cardiac myocytes from pluripotent stem cells and lead to novel therapeutic approaches targeted to the mitochondria.

To independently control tissue alignment and ECM elasticity, we microcontact printed fibronectin onto tunable PDMS disks with elastic moduli ranging from developmental to supraphysiological ranges. Although these polymer surfaces are highly synthetic, the ability to independently control ECM patterning and elasticity is a clear advantage compared with natural, ECM-derived biomaterials, such as Matrigel or gelatin hydrogels. For example, the elastic modulus of gelatin hydrogels is dictated by the percentage of gelatin (42), and thus it is impossible to decouple ECM ligand concentration from the elastic modulus. PDMS is also relatively easy to fabricate and handle compared with other synthetic biomaterials, such as polyacrylamide hydrogels (43, 46). Thus our approach was relatively simple while also facilitating a high degree of control over the two parameters of interest. Importantly, many other biochemical assays beyond those reported here rely on measuring properties, such as absorbance or luminescence, from cells cultured within microwell plates. Our approach for regulating ECM elasticity and patterning can easily be adapted for many assays that are performed within standard plate readers, broadly expanding the applications for our technology.

Our OCR measurements revealed a variety of unique relationships between tissue architecture, ECM elasticity, and different aspects of mitochondrial function. Basal respiration and ATP production are both associated with baseline mitochondrial function and showed relatively similar trends: both parameters showed increases with increasing elastic modulus, with more pronounced trends in aligned tissues compared with isotropic tissues. Correlations between basal respiration, ATP production, and elastic modulus are likely due to the increased demand for ATP in more rigid microenvironments, which increases the resistance to myocyte shortening. However, tissue alignment has relatively minimal impact on these parameters, indicating that ECM elasticity dominates over tissue alignment for the regulation of baseline mitochondrial function.

Maximum respiration and spare respiratory capacity reflect the ability of myocytes to adapt to increased metabolic demands in times of stress. Interestingly, we observed differences in these parameters only in aligned tissues, not isotropic tissues. Specifically, in aligned tissues, both maximum respiration and spare respiratory capacity were highest on the most rigid substrate. This suggests that the ability of mitochondria to adapt to metabolic stress and increased demand for ATP is maximized when both tissue alignment and ECM rigidity are high. We also observed nonmonotonic increases in maximum respiration and spare respiratory capacity with ECM elasticity in aligned tissues. This is an intriguing result and is suggestive of nonlinear relationships between ECM elasticity and these two metabolic parameters in aligned tissues, which can be explored in future studies.

Proton leak is indicative of mitochondrial efficiency (35) and was the only parameter regulated by tissue alignment based on our two-way ANOVA analysis, with lower values in aligned tissues. However, our one-way ANOVA analysis showed no differences due solely to tissue alignment or ECM elasticity, if the other parameter is kept constant. Thus proton leak seems to be slightly affected by tissue alignment, but not as robustly as most of the other parameters we measured. Importantly, nonmitochondrial respiration was preserved across all conditions, suggesting that tissues were relatively consistent in terms of cell density, composition, and overall health. This conclusion is also supported by our immunostaining and protein content data. To characterize overall mitochondrial health, we also calculated the BHI. This parameter combines the positive (ATP production and spare respiratory capacity) and negative (proton leak and nonmitochondrial respiration) metrics of mitochondrial function (11). We found that this value was maximized in aligned tissues on the most rigid substrates, suggesting that both ECM elasticity and tissue alignment play a role in overall mitochondrial health.

Our data have important biological significance to both cardiac development and disease. During cardiac development, myocytes gradually elongate and self-assemble into aligned tissues (31). Concurrently, the elastic modulus of the ECM (20) and the hemodynamic load (33) increases, which both elevate the afterload on cardiac myocytes. Our experimental conditions most relevant to these transitions are the isotropic and aligned tissues on low and moderate substrates. Within this subset of data, basal respiration and ATP production both increase with ECM rigidity, suggesting that myocytes increase their baseline metabolism as their afterload increases during development. However, maximum respiration and spare respiratory capacity were less affected by ECM elasticity, suggesting that mitochondrial adaptation to stress is not regulated by ECM elasticity or potentially other increases in afterload during development. In general, tissue alignment had minimal impact on any parameter on low and moderate substrates, suggesting that the elongation and alignment of cardiac myocytes does not play a predominant role in the functional maturation of mitochondria during development.

Many cardiac diseases are associated with increased hemodynamic load (28, 49), increased ECM rigidity (7, 17), and/or disorganization of cardiac myocytes (41), often secondary to fibrosis (53). Our measurements from isotropic and aligned tissues on moderate and high substrates can be used to understand the impact of these pathological transitions on mitochondrial function. In isotropic tissues, all mitochondrial parameters were similar on moderate and high substrates. However, in aligned tissues, basal respiration, ATP production, maximum respiration, and spare respiratory capacity each increased on the high substrate compared with the moderate substrate. Thus aligned tissues appear to be more adaptable to increases in ECM rigidity and/or afterload in pathological settings, which could be a compensatory response to generate sufficient ATP to increase contractile output in response to increased load. Thus preservation of tissue alignment seems to be most critical for maintaining, or even enhancing, mitochondrial function in diseased settings.

In many forms of pathological hypertrophy, compensatory mechanisms are temporary and eventually transition to pathological remodeling and heart failure (6, 22). Importantly, reactive oxygen species are a natural by-product of mitochondrial respiration, which can lead to oxidative stress long term (24). Oxidative stress has been observed in many cardiac diseases (26, 32, 55). This could be due, in part, to increased ATP production due to increased load in pathological environments. Because of the timescale of our experiments, we are likely capturing responses more similar to early compensatory stages and thus may not observe the deleterious effects of oxidative stress. Thus correlating mitochondrial function to oxidative stress at extended time points is an important subject for future studies.

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that undergo biogenesis, fusion, fission, and mitophagy (12, 18, 24, 30). Relative to other cell types, mitochondria in cardiac myocytes are relatively static and highly fragmented because they must pack tightly next to myofibrils for efficient delivery of ATP to sarcomeres (4, 19). Thus myofibril architecture, mitochondrial structure, and mitochondrial function are closely related. Our laboratory and others have previously shown that sarcomere alignment and force generation are regulated by both myocyte shape and tissue alignment, but not always linearly (21, 27, 38, 43, 46). Altered mitochondrial structure and/or function secondary to differences in sarcomere and myofibril architecture could be a missing piece of this puzzle. Furthermore, alterations in biogenesis, fusion, fission, and mitophagy are associated with cardiac differentiation and maturation (5, 14, 34) as well as many cardiac diseases (3, 23, 58, 59). Thus characterizing mitochondrial fragmentation and turnover due to ECM elasticity and tissue architecture could provide mechanistic insight into some of our results.

Our study has many inherent limitations. For example, our engineered cardiac tissues lacked important components of native myocardium, such as supporting cell populations, vascularization, three-dimensional architecture, and mechanical stimulation. However, for this study, we chose to minimize complexity such that we could delineate the impact of ECM elasticity and tissue alignment on cardiac myocytes specifically. Future studies can focus on determining the metabolic impact of additional features of native myocardium, such as cardiac fibroblasts, and modeling more complex pathophysiological conditions, such as ischemia or hypertrophy. We also used fibronectin as the sole ECM protein, but the native basal lamina in the myocardium consists of many diverse proteins and macromolecules (60), which also remodel in development and disease (44) and could potentially impact mitochondrial function as well. Additionally, we could not fully replicate the nutrient sources present in native blood. Our media contained glucose and amino acids, but no fatty acids, which are known to be present in vivo. Furthermore, we measured OCR within intact engineered tissues instead of isolated mitochondria. Hence, we cannot conclude if the differences we observed are caused by intrinsic changes to mitochondria, the total quantity of mitochondria, or the architecture of the mitochondria within the cell (29, 48), which is known to impact mitochondrial function.

Another limitation of our study is the use of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes, which are nonhuman. However, the only renewable sources of human cardiac myocytes are those differentiated from pluripotent stem cells, which are relatively heterogeneous and immature (54, 61), and, therefore, would likely not provide clear results. Nevertheless, our platform should be compatible with identifying how mitochondrial function in human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac myocytes with disease-relevant genetic mutations is also impacted by ECM elasticity and tissue architecture. This is especially relevant for mitochondrial cardiomyopathies, such as Barth Syndrome (61), which are often characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction as well as fibrosis. Thus our platform could provide new insights into how genetic mutations impair mitochondrial function and identify new avenues for therapeutic interventions that can recover the function of these organelles.

In conclusion, we developed a novel approach to tune both ECM elasticity and tissue alignment within cell culture microplates. This approach allowed us to measure OCR in engineered cardiac tissues due to these two variables. Our findings demonstrate that baseline mitochondrial function is predominantly regulated by ECM elasticity, but the ability of mitochondria to adapt to stress is regulated by both ECM elasticity and tissue alignment. Our data complement existing in vivo studies that have reported remodeling of mitochondrial function in developmental and pathological settings. Our results also provide further evidence that ECM elasticity, myofibril architecture, contractility, and mitochondrial function are all interrelated, emphasizing that each of these factors is important to consider in the context of cardiac development, maturation, and disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by American Heart Association Scientist Development Grants 16SDG29950005 (to M.L.M.) and 15SDG23230013 (to A.M.A.); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant P01-HL-112730 (to R.A.G.); USC Viterbi School of Engineering, USC Graduate School (Annenberg Fellowship to D.M.L.-L., Provost Fellowship to N.R.A. and N.C., and Rose Hills Fellowship to A.P.P.), USC Women in Science and Engineering, and USC Viterbi School of Engineering Summer High School Intensive in Next-Generation Engineering.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.M.L.-L. and M.L.M. conceived and designed research; D.M.L.-L., A.M.A., A.P.P., N.R.A., N.C., and J.A.L. performed experiments; D.M.L.-L., A.M.A., and M.L.M. analyzed data; D.M.L.-L., A.M.A., R.A.G., and M.L.M. interpreted results of experiments; D.M.L.-L. and M.L.M. prepared figures; D.M.L.-L. and M.L.M. drafted manuscript; D.M.L.-L., A.M.A., A.P.P., N.R.A., N.C., J.A.L., R.A.G., and M.L.M. edited and revised manuscript; D.M.L.-L., A.M.A., A.P.P., N.R.A., N.C., J.A.L., R.A.G., and M.L.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the W.M. Keck Foundation Photonics Center Cleanroom for photolithography equipment and facilities. We acknowledge the Cedars-Sinai Metabolism and Mitochondrial Research Core for Seahorse Extracellular Flux Analyzer equipment and facilities. We thank Suyon Sarah Kim for help with cell counting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal A, Farouz Y, Nesmith AP, Deravi LF, McCain ML, Parker KK. Micropatterning alginate substrates for in vitro cardiovascular muscle on a chip. Adv Funct Mater 23: 3738–3746, 2013. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201203319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andres AM, Stotland A, Queliconi BB, Gottlieb RA. A time to reap, a time to sow: mitophagy and biogenesis in cardiac pathophysiology. J Mol Cell Cardiol 78: 62–72, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andres AM, Tucker KC, Thomas A, Taylor DJ, Sengstock D, Jahania SM, Dabir R, Pourpirali S, Brown JA, Westbrook DG, Ballinger SW, Mentzer RM Jr, Gottlieb RA. Mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis in atrial tissue of patients undergoing heart surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. JCI Insight 2: e89303, 2017. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrienko T, Kuznetsov AV, Kaambre T, Usson Y, Orosco A, Appaix F, Tiivel T, Sikk P, Vendelin M, Margreiter R, Saks VA. Metabolic consequences of functional complexes of mitochondria, myofibrils and sarcoplasmic reticulum in muscle cells. J Exp Biol 206: 2059–2072, 2003. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anmann T, Varikmaa M, Timohhina N, Tepp K, Shevchuk I, Chekulayev V, Saks V, Kaambre T. Formation of highly organized intracellular structure and energy metabolism in cardiac muscle cells during postnatal development of rat heart. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837: 1350–1361, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anversa P, Ricci R, Olivetti G. Quantitative structural analysis of the myocardium during physiologic growth and induced cardiac hypertrophy: a review. J Am Coll Cardiol 7: 1140–1149, 1986. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(86)80236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry MF, Engler AJ, Woo YJ, Pirolli TJ, Bish LT, Jayasankar V, Morine KJ, Gardner TJ, Discher DE, Sweeney HL. Mesenchymal stem cell injection after myocardial infarction improves myocardial compliance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H2196–H2203, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01017.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bettadapur A, Suh GC, Geisse NA, Wang ER, Hua C, Huber HA, Viscio AA, Kim JY, Strickland JB, McCain ML. Prolonged culture of aligned skeletal myotubes on micromolded gelatin hydrogels. Sci Rep 6: 28855, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep28855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bugger H, Schwarzer M, Chen D, Schrepper A, Amorim PA, Schoepe M, Nguyen TD, Mohr FW, Khalimonchuk O, Weimer BC, Doenst T. Proteomic remodelling of mitochondrial oxidative pathways in pressure overload-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 85: 376–384, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bursac N, Parker KK, Iravanian S, Tung L. Cardiomyocyte cultures with controlled macroscopic anisotropy: a model for functional electrophysiological studies of cardiac muscle. Circ Res 91: e45–e54, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000047530.88338.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chacko BK, Zhi D, Darley-Usmar VM, Mitchell T. The Bioenergetic Health Index is a sensitive measure of oxidative stress in human monocytes. Redox Biol 8: 43–50, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Liu Y, Dorn GW II. Mitochondrial fusion is essential for organelle function and cardiac homeostasis. Circ Res 109: 1327–1331, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung S, Arrell DK, Faustino RS, Terzic A, Dzeja PP. Glycolytic network restructuring integral to the energetics of embryonic stem cell cardiac differentiation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 725–734, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung S, Dzeja PP, Faustino RS, Perez-Terzic C, Behfar A, Terzic A. Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is required for the cardiac differentiation of stem cells. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 4, Suppl 1: S60–S67, 2007. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dedkova EN, Blatter LA. Measuring mitochondrial function in intact cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52: 48–61, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doenst T, Pytel G, Schrepper A, Amorim P, Färber G, Shingu Y, Mohr FW, Schwarzer M. Decreased rates of substrate oxidation ex vivo predict the onset of heart failure and contractile dysfunction in rats with pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res 86: 461–470, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doering CW, Jalil JE, Janicki JS, Pick R, Aghili S, Abrahams C, Weber KT. Collagen network remodelling and diastolic stiffness of the rat left ventricle with pressure overload hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 22: 686–695, 1988. doi: 10.1093/cvr/22.10.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorn GW., II Mitochondrial dynamics in heart disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833: 233–241, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorn GW II, Vega RB, Kelly DP. Mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics in the developing and diseased heart. Genes Dev 29: 1981–1991, 2015. doi: 10.1101/gad.269894.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engler AJ, Carag-Krieger C, Johnson CP, Raab M, Tang HY, Speicher DW, Sanger JW, Sanger JM, Discher DE. Embryonic cardiomyocytes beat best on a matrix with heart-like elasticity: scar-like rigidity inhibits beating. J Cell Sci 121: 3794–3802, 2008. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feinberg AW, Alford PW, Jin H, Ripplinger CM, Werdich AA, Sheehy SP, Grosberg A, Parker KK. Controlling the contractile strength of engineered cardiac muscle by hierarchal tissue architecture. Biomaterials 33: 5732–5741, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frey N, Katus HA, Olson EN, Hill JA. Hypertrophy of the heart: a new therapeutic target? Circulation 109: 1580–1589, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120390.68287.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong G, Song M, Csordas G, Kelly DP, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW II. Parkin-mediated mitophagy directs perinatal cardiac metabolic maturation in mice. Science 350: aad2459, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gottlieb RA, Bernstein D. Mitochondrial remodeling: rearranging, recycling, and reprogramming. Cell Calcium 60: 88–101, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottlieb RA, Stotland A. MitoTimer: a novel protein for monitoring mitochondrial turnover in the heart. J Mol Med (Berl) 93: 271–278, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1230-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grieve DJ, Byrne JA, Cave AC, Shah AM. Role of oxidative stress in cardiac remodelling after myocardial infarction. Heart Lung Circ 13: 132–138, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grosberg A, Alford PW, McCain ML, Parker KK. Ensembles of engineered cardiac tissues for physiological and pharmacological study: heart on a chip. Lab Chip 11: 4165–4173, 2011. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20557a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grossman W, Jones D, McLaurin LP. Wall stress and patterns of hypertrophy in the human left ventricle. J Clin Invest 56: 56–64, 1975. doi: 10.1172/JCI108079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guzun R, Gonzalez-Granillo M, Karu-Varikmaa M, Grichine A, Usson Y, Kaambre T, Guerrero-Roesch K, Kuznetsov A, Schlattner U, Saks V. Regulation of respiration in muscle cells in vivo by VDAC through interaction with the cytoskeleton and mtCK within mitochondrial interactosome. Biochim Biophys Acta 1818: 1545–1554, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall AR, Burke N, Dongworth RK, Hausenloy DJ. Mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins: novel therapeutic targets for combating cardiovascular disease. Br J Pharmacol 171: 1890–1906, 2014. doi: 10.1111/bph.12516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirschy A, Schatzmann F, Ehler E, Perriard JC. Establishment of cardiac cytoarchitecture in the developing mouse heart. Dev Biol 289: 430–441, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hori M, Nishida K. Oxidative stress and left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 81: 457–464, 2009. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu N, Clark EB. Hemodynamics of the stage 12 to stage 29 chick embryo. Circ Res 65: 1665–1670, 1989. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.65.6.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishihara T, Ban-Ishihara R, Maeda M, Matsunaga Y, Ichimura A, Kyogoku S, Aoki H, Katada S, Nakada K, Nomura M, Mizushima N, Mihara K, Ishihara N. Dynamics of mitochondrial DNA nucleoids regulated by mitochondrial fission is essential for maintenance of homogeneously active mitochondria during neonatal heart development. Mol Cell Biol 35: 211–223, 2015. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01054-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jastroch M, Divakaruni AS, Mookerjee S, Treberg JR, Brand MD. Mitochondrial proton and electron leaks. Essays Biochem 47: 53–67, 2010. doi: 10.1042/bse0470053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaswal JS, Cadete VJJ, Lopaschuk GD. Optimizing cardiac energy substrate metabolism: a novel therapeutic intervention for ischemic heart disease. Heart Metab 38: 5–14, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaushik G, Engler AJ. From Stem Cells to Cardiomyocytes: the Role of Forces in Cardiac Maturation, Aging, and Disease. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2014, p. 219–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knight MB, Drew NK, McCarthy LA, Grosberg A. Emergent global contractile force in cardiac tissues. Biophys J 110: 1615–1624, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopaschuk GD, Jaswal JS. Energy metabolic phenotype of the cardiomyocyte during development, differentiation, and postnatal maturation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 56: 130–140, 2010. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181e74a14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Majkut S, Idema T, Swift J, Krieger C, Liu A, Discher DE. Heart-specific stiffening in early embryos parallels matrix and myosin expression to optimize beating. Curr Biol 23: 2434–2439, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsushita T, Oyamada M, Fujimoto K, Yasuda Y, Masuda S, Wada Y, Oka T, Takamatsu T. Remodeling of cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions at the border zone of rat myocardial infarcts. Circ Res 85: 1046–1055, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.85.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCain ML, Agarwal A, Nesmith HW, Nesmith AP, Parker KK. Micromolded gelatin hydrogels for extended culture of engineered cardiac tissues. Biomaterials 35: 5462–5471, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCain ML, Lee H, Aratyn-Schaus Y, Kléber AG, Parker KK. Cooperative coupling of cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesions in cardiac muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 9881–9886, 2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203007109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCain ML, Parker KK. Mechanotransduction: the role of mechanical stress, myocyte shape, and cytoskeletal architecture on cardiac function. Pflugers Arch 462: 89–104, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0951-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCain ML, Sheehy SP, Grosberg A, Goss JA, Parker KK. Recapitulating maladaptive, multiscale remodeling of failing myocardium on a chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 9770–9775, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304913110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCain ML, Yuan H, Pasqualini FS, Campbell PH, Parker KK. Matrix elasticity regulates the optimal cardiac myocyte shape for contractility. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H1525–H1539, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00799.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mdaki KS, Larsen TD, Weaver LJ, Baack ML. Age related bioenergetics profiles in isolated rat cardiomyocytes using extracellular flux analyses. PLoS One 11: e0149002, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miragoli M, Sanchez-Alonso JL, Bhargava A, Wright PT, Sikkel M, Schobesberger S, Diakonov I, Novak P, Castaldi A, Cattaneo P, Lyon AR, Lab MJ, Gorelik J. Microtubule-dependent mitochondria alignment regulates calcium release in response to nanomechanical stimulus in heart myocytes. Cell Reports 14: 140–151, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nadruz W. Myocardial remodeling in hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 29: 1–6, 2015. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2014.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neubauer S. The failing heart—an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med 356: 1140–1151, 2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra063052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palchesko RN, Zhang L, Sun Y, Feinberg AW. Development of polydimethylsiloxane substrates with tunable elastic modulus to study cell mechanobiology in muscle and nerve. PLoS One 7: e51499, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qin D, Xia Y, Whitesides GM. Soft lithography for micro- and nanoscale patterning. Nat Protoc 5: 491–502, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Segura AM, Frazier OH, Buja LM. Fibrosis and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 19: 173–185, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sheehy SP, Pasqualini F, Grosberg A, Park SJ, Aratyn-Schaus Y, Parker KK. Quality metrics for stem cell-derived cardiac myocytes. Stem Cell Reports 2: 282–294, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sugamura K, Keaney JF Jr. Reactive oxygen species in cardiovascular disease. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 978–992, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor D, Gottlieb RA. Parkin-mediated mitophagy is downregulated in browning of white adipose tissue. Obesity (Silver Spring) 25: 704–712, 2017. doi: 10.1002/oby.21786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tiivel T, Kadaya L, Kuznetsov A, Käämbre T, Peet N, Sikk P, Braun U, Ventura-Clapier R, Saks V, Seppet EK. Developmental changes in regulation of mitochondrial respiration by ADP and creatine in rat heart in vivo. Mol Cell Biochem 208: 119–128, 2000. doi: 10.1023/A:1007002323492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vásquez-Trincado C, García-Carvajal I, Pennanen C, Parra V, Hill JA, Rothermel BA, Lavandero S. Mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy and cardiovascular disease. J Physiol 594: 509–525, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP271301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wai T, García-Prieto J, Baker MJ, Merkwirth C, Benit P, Rustin P, Rupérez FJ, Barbas C, Ibañez B, Langer T. Imbalanced OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fragmentation cause heart failure in mice. Science 350: aad0116, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walker CA, Spinale FG. The structure and function of the cardiac myocyte: a review of fundamental concepts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 118: 375–382, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang G, McCain ML, Yang L, He A, Pasqualini FS, Agarwal A, Yuan H, Jiang D, Zhang D, Zangi L, Geva J, Roberts AE, Ma Q, Ding J, Chen J, Wang DZ, Li K, Wang J, Wanders RJ, Kulik W, Vaz FM, Laflamme MA, Murry CE, Chien KR, Kelley RI, Church GM, Parker KK, Pu WT. Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies. Nat Med 20: 616–623, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nm.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]