Abstract

The hepatic lipase (LIPC) locus is a well-established determinant of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations, an association that is modified by dietary fat in observational studies. Dietary interventions are lacking. We investigated dietary modulation of LIPC rs1800588 (−514 C/T) for lipids and glucose using a randomized crossover design comparing a high-fat Western diet and a low-fat traditional Hispanic diet in individuals of Caribbean Hispanic descent (n = 42, 4 wk/phase). No significant gene-diet interactions were observed for HDL-C. However, differences in dietary response according to LIPC genotype were observed. In major allele carriers (CC/CT), HDL-C (mmol/l) was higher following the Western diet compared with the Hispanic diet: phase 1 (Western: 1.3 ± 0.03; Hispanic: 1.1 ± 0.04; P = 0.0004); phase 2 (Western: 1.4 ± 0.03; Hispanic: 1.2 ± 0.03; P = 0.0003). In contrast, HDL-C in TT individuals did not differ by diet. Only major allele carriers benefited from the higher-fat diet for HDL-C. Secondarily, we explored dietary fat quality and rs1800588 for HDL-C and triglycerides (TG) in a Boston Puerto Rican Health Study (BPRHS) subset matched for diabetes and obesity status (subset n = 384). In the BPRHS, saturated fat was unfavorably associated with HDL-C and TG in rs1800588 TT carriers. LIPC rs1800588 appears to modify plasma lipids in the context of dietary fat. This new evidence of genetic modulation of dietary responses may inform optimal and personalized dietary fat advice and reinforces the importance of studying genetic markers in diet and cardiometabolic health.

Keywords: Caribbean Hispanics, hepatic lipase, dietary fat, intervention, Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, LIPC

while consensus has been achieved on many of the defining characteristics of healthy diets, debate about the optimal macronutrient composition (e.g., fat vs. carbohydrates) for cardiovascular health persists (29, 34). Although lower-fat diets were recommended through 2000 (12), these recommendations shifted to moderate-fat, lower-carbohydrate diets, particularly refined carbohydrate, thereafter (14). Higher-fat diets, particularly higher in unsaturated fat, are thought to be cardioprotective, in part, because they result in higher high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and lower triglyceride (TG) concentrations (2). However, considerable interindividual variability in response to dietary fat and carbohydrate exists, and assessments of gene-diet interactions have identified variants in regulators of lipoprotein metabolism that contribute to differential responses (4).

One such regulator is hepatic lipase, which hydrolyzes TGs and phospholipids and provides a ligand-binding function for the uptake of lipoproteins and lipoprotein lipids (22). Therefore, hepatic lipase (LIPC) is a plausible candidate locus for plasma HDL-C and TG concentrations (27, 33). The nucleotide substitution that creates the LIPC −514 C/T promoter variant (rs1800588) has been shown to decrease hepatic lipase activity. Hepatic lipase activity is a major determinant of HDL-C concentration, such that higher lipase activity contributes to lower HDL-C (3) concentrations. The LIPC −514 C/T variant’s association with lower hepatic lipase activity provides a functional basis for its association with higher HDL-C concentrations (8). However, the variant’s inconsistent associations with plasma HDL-C and TG concentrations (5, 19, 25, 32) suggested that other factors, including diet, might modulate its association with lipids.

Gene-diet interaction analyses support the premise that total dietary fat and types of fat [monounsaturated (MUFA), polyunsaturated (PUFA), and saturated (SFA)] modify LIPC −514 C/T associations with HDL-C concentration (19, 25). While higher fat intake is usually associated with higher HDL-C concentration when genotype is not considered, LIPC −514 C/T modified this association, such that higher total fat (19, 25) and higher SFA (19) were associated with lower HDL-C concentration in minor allele T carriers. Furthermore, recognition of the coupling between lipid and glucose metabolism led to investigation of the potential role of LIPC −514 C/T in glycemic outcomes (6, 30).

While observational studies can generate hypotheses, interventions provide a higher level of evidence. To rigorously investigate the hypothesis that dietary fat intake modifies LIPC −514 C/T associations with HDL-C concentration, we conducted a crossover, randomized intervention using two diets, a high-fat Western diet and a low-fat traditional Hispanic diet, in Caribbean Hispanics. Secondarily, given the absence of studies for diet and LIPC −514 C/T in Caribbean Hispanics, we explored interactions between dietary fat and genotype for lipids in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study (BPRHS).

METHODS

Study population and design.

We conducted a crossover, randomized dietary intervention to evaluate interactions between LIPC −514 C/T, two diets of different fat content, and plasma lipids in Caribbean Hispanics living in the Boston, MA, metropolitan area. Individuals aged 20−64 yr with self-reported Caribbean Hispanic ancestry were recruited from January 2008−July 2011. Study exclusions included: diabetes (fasting glucose >140 mg/dl), other chronic disease, lipid-lowering or hypoglycemic medications, body mass index (BMI) >34 kg/m2, excessive alcohol, smoking within 6 mo, pregnancy/lactation, recent weight change, extreme physical activity, vegetarians/vegans, and food allergies. The Tufts University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the protocol, and informed written consent was obtained. The principal investigator was blinded to the randomization scheme until study completion. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT02938091).

Diet procedures.

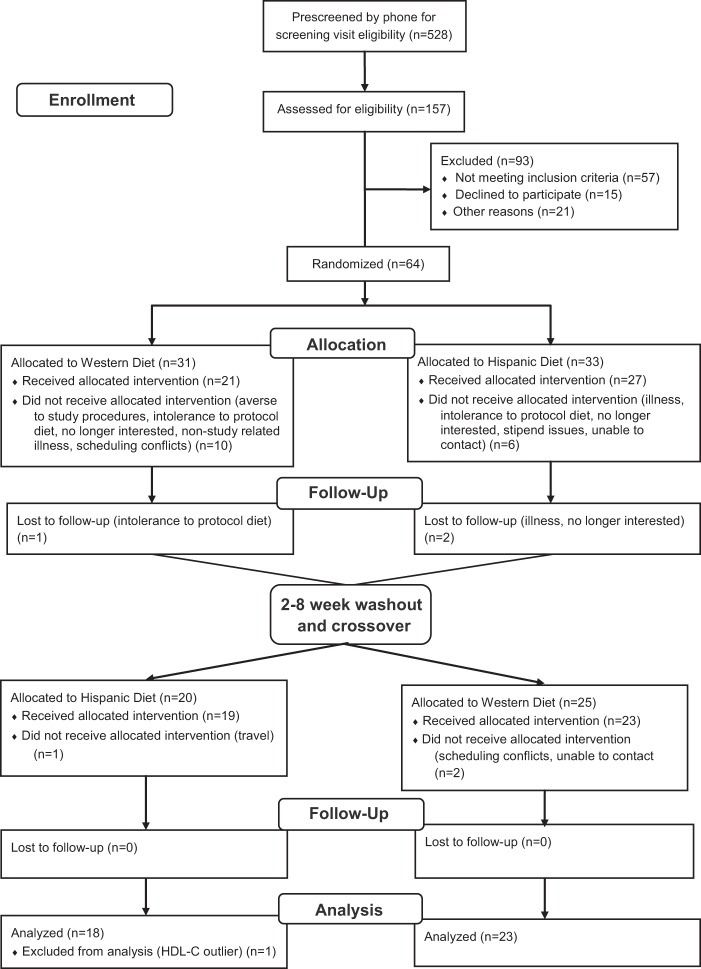

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) chart documents the flow of participants through the intervention processes including screening, enrollment, randomization, follow-up, washout, crossover, and analysis (Fig. 1). The CONSORT chart was developed by the CONSORT group to improve and standardize the reporting of randomized controlled trials (17).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT chart documents the flow of participants through the intervention processes. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

In brief, participants were randomized to one of two study diets for 4 wk, followed by a 2–8 wk break period before beginning the second diet for 4 wk. A 4 wk diet period was chosen to enable stabilization of the lipoprotein end points and to facilitate recruitment and adherence. Participants were provided with a high-fat Western diet (39% fat) and a low-fat traditional Hispanic diet (20% fat) based on their random order assignment (Table 1). A registered dietitian calculated the estimated energy requirements to maintain each participant’s body weight, with adjustments to keep weight stable. All foods and beverages were provided by the research kitchen with no other foods permitted. Participants were asked to eat all of the food provided.

Table 1.

Nutrient profiles of intervention diets

| Nutrient | High-fat Western Diet | Low-fat Hispanic Diet |

|---|---|---|

| Total fat, % total energy | 39.3 | 20.4 |

| SFA, % total energy | 14.4 | 5.5 |

| MUFA, % total energy | 12.4 | 9.6 |

| PUFA, % total energy | 9.6 | 3.7 |

| SFA, % total fat | 36.6 | 27 |

| MUFA, % total fat | 31.5 | 47 |

| PUFA, % total fat | 24.4 | 18.1 |

| Cholesterol, mg/1,000 kcal | 149 | 76.5 |

| Protein, % total energy | 20.2 | 20.5 |

| Carbohydrate, % total energy | 41.6 | 61.0 |

| Added sugar, g/1,000 kcal | 6.7 | 24.6 |

| Total fiber, g/1,000 kcal | 8.8 | 13.7 |

| Soluble fiber, g/1,000 kcal | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| Insoluble fiber, g/1,000 kcal | 6.0 | 10.3 |

SFA, saturated fatty acids; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acids.

All study visits were conducted at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (HNRCA), by bilingual study coordinators and Metabolic Research Unit staff. Each study phase consisted of 12 visits, usually requiring 1–3 h/visit. Participants were required to eat at least three meals per week at the HNRCA. The remainder of the weekly food and beverages was prepackaged for each participant.

Data collection.

Venous blood was collected at four visits, including baseline, and in week 3 of each phase for an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Individuals fasted for 12 h before each blood draw, including for the OGTT determination. Anthropometrics were measured by standardized protocols. Diet was assessed from a food frequency questionnaire designed and validated for Caribbean Hispanics. Intervention compliance was maximized and monitored with ongoing interaction between participants and study coordinators.

Genotyping and biochemical analyses.

DNA was isolated and purified for PCR analysis with the QIAamp Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and LIPC rs1800588 genotyping was performed with the TaqMan assay (Perkin-Elmer). Fasting total cholesterol and TG concentrations were determined by automated enzymatic methods, and HDL-C was measured following precipitation of plasma very-low-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) with dextran sulfate-Mg2+. LDL-C was measured directly using LDL-Direct (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO). Glucose was measured by a glucose oxidase enzymatic procedure (Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY).

BPRHS.

To extend analyses to a larger Hispanic sample, we investigated interactions between dietary fat and LIPC rs1800588 for HDL-C and TG concentration in the BPRHS. The longitudinal cohort BPRHS examined health status in Puerto Ricans, and modification of cardiometabolic biomarkers by nutritional status and genetic variation as previously described (11, 15, 16, 18, 28). Participants were self-identified Puerto Ricans, aged 45–75 yr, residing in metropolitan Boston, MA, and for whom genome-wide genotypes, dietary, lifestyle, medical, biochemical, and socio-economic data were obtained. The BPRHS averages 57.2% European, 27.4% African, and 15.4% American Indian ancestry (13). The study was approved by the Tufts University, Northeastern University, and the University of Massachusetts-Lowell IRBs. Participants provided written informed consent.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed with SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Categorical traits were compared by Pearson’s χ2-test, except for sex for which Fisher’s exact test was used. Continuous variables were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA). TGs were log-transformed to improve distribution. For the dietary intervention, initial linear mixed effects models included phase, dietary intervention, diet-phase interaction, LIPC rs1800588 genotype, diet-genotype interaction, and a random subject effect. Because no carryover effect was detected between diet phases (P = 0.89), the diet-phase interaction term was removed from subsequent analyses. We tested for single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) × sex interactions to determine whether sex-stratified analyses of the intervention data were statistically justified. The interaction term was not significant so intervention data were analyzed with both sexes combined. Potential confounders included age, sex, waist, and baseline lipid or pre-OGTT glucose concentration. Interaction analyses were conducted using generalized linear model regressions.

Analyses were conducted in a BPRHS subset with exclusions similar to those applied in the intervention (BMI ≤34, without diabetes). We dichotomized dietary exposures for total fat, PUFA, MUFA, and SFA (% total energy) into high and low according to the median population intake, and evaluated interactions between diet and LIPC genotype for HDL-C, LDL-C, total cholesterol, and TG. Models were adjusted for age, smoking status, alcohol, total energy, waist, physical activity, and ancestry.

RESULTS

Crossover dietary intervention.

Forty-two participants completed the trial, including one who was subsequently excluded due to unusually high HDL-C (124 mg/dl) concentration, leaving 41 in the analytic sample. A CONSORT chart documents the flow of participants through the intervention trial (Fig. 1). Of 41 participants (aged: 20–64 yr, 80% female) national origins included: Dominican (n = 25), Puerto Rican (n = 9), and other Caribbean Hispanics and Central Americans (n = 7).

The minor allele (T) frequency (MAF) was 40.2%. Nutrient profiles of the two diet interventions confirmed higher fat (total and all types) and lower carbohydrate in the Western diet (Table 1). Baseline cardiometabolic traits measured before the dietary intervention did not differ across genotypes. HDL-C concentration was marginally higher with TT genotype (P = 0.05, Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics by LIPC −514 C/T genotype

| C/C (n = 16) | C/T (n = 17) | T/T (n = 8) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 39.9 (10.4) | 44.8 (11.2) | 35.4 (13.5) | 0.15 |

| Female, n (%) | 12 (75%) | 13 (76%) | 8 (100%) | 0.36 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.9 (3.2) | 27.0 (3.3) | 29.3 (3.4) | 0.26 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 85.5 (7.6) | 84.9 (7.8) | 90.4 (8.2) | 0.29 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/l [mg/dl] | 4.7 (0.8) [183 (33.6)] | 4.7 (0.8) [182 (34.2)] | 5.4 (0.8) [207 (36.2)] | 0.26 |

| LDL-C, mmol/l [mg/dl] | 3 (0.8) [117 (28.4] | 2.8 (0.8) [109 (28.9)] | 3.2 (0.8) [124 (30.5)] | 0.51 |

| HDL-C, mmol/l [mg/dl] | 1.2 (0.4) [46.7 (9.6)] | 1.3 (0.4) [51.5 (9.9)] | 1.5 (0.3) [57.7 (10.2)] | 0.05 |

| TG, GM (95% CI), mmol/l [mg/dl] | 1 (0.7, 1.3) [85.8 (66, 112)] | 1 (0.7, 1.2) [84.9 (65.3, 110)] | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) [106 (71.3, 159)] | 0.62 |

| Glucose, mmol/l [mg/dl] | 5 (0.4) [89.3 (8)] | 4.8 (0.4) [86.7 (8)] | 4.9 (0.6) [88.9 (9)] | 0.64 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 119 (14) | 116 (14.4) | 115 (15.3) | 0.74 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 75.3 (7.6) | 78.9 (7.8) | 71.2 (8.2) | 0.11 |

Data are means (SD) except where otherwise indicated. Laboratory measurements were made before the dietary intervention was begun. Continuous variables were compared across LIPC genotypes by analysis of variance. Proportion of females across LIPC genotypes was compared by Fisher’s exact test. Body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference were adjusted for age and sex. Lipids, glucose, and blood pressure measures were adjusted for age, sex, and baseline waist circumference. TGs were log-transformed to improve distribution. CI, confidence interval; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

We first evaluated the effect of dietary interventions without considering genotype for HDL-C, TG, LDL-C, total cholesterol, and OGTT 2 h glucose concentrations (Table 3). With all genotypes combined, consumption of the Western diet was associated with higher postintervention HDL-C, LDL-C, and total cholesterol concentrations, compared with the Hispanic diet (Table 3, all P ≤ 0.02). However, TG and OGTT 2 h glucose concentration did not differ between diets.

Table 3.

Main effects of diet on HDL-C, TG, and 2-h OGTT concentrations at end of intervention diets

| High-fat Western Diet | Low-fat Traditional Hispanic Diet | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDL-C, mmol/l [mg/dl] | 1.34 (0.03) [51.8 (1.0)] | 1.21 (0.03) [46.7 (1.0)] | <0.0001 |

| TG, mmol/l [mg/dl] | 0.95 (0.8, 1.11) [83.8 (71.1, 98.7)] | 0.93 (0.79, 1.09) [82.2 (69.9, 96.7)] | 0.76 |

| LDL-C, mmol/l [mg/dl] | 3.0 (0.09) [116 (3.5)] | 2.7 (0.09) [103 (3.6)] | 0.02 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/l [mg/dl] | 4.9 (0.1) [188 (3.7)] | 4.4 (0.09) [171 (3.6)] | 0.0002 |

| OGTT 2 h glucose, mmol/l [mg/dl] | 4.9 (0.2) [87.6 (3.6)] | 5.0 (0.2) [90.1 (3.7)] | 0.44 |

Values are means (SE) except for TG, which is geometric mean (95% CI). Mixed model regression was used to obtain mean HDL-C concentrations at end of intervention periods, adjusting for phase, age, sex, baseline HDL-C and waist circumference, and post-diet TG concentration. Mixed model regression was used to obtain geometric mean TG concentrations at end of intervention periods, adjusting for phase, age, sex, baseline TGs, and waist circumference, and postdiet HDL-C concentration. Mixed model regression was used to obtain mean LDL-C and total cholesterol concentrations at end of intervention periods, adjusting for phase, age, sex, baseline lipid concentration, and waist circumference. Mixed model regression was used to obtain mean 2 h OGTT glucose concentrations, adjusting for phase, age, sex, baseline waist circumference, and preload glucose. P values are for difference between diets. HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein lipase; TG, triglyceride; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

We next evaluated gene-diet interactions, including analysis by dietary phase for HDL-C, LDL-C, and total cholesterol (Table 4). Based on published data for HDL-C (16), we applied a recessive genetic model (CC/CT, n = 33; vs. TT, n = 8) to evaluate lipids. No significant interaction was observed between SNP and diet for HDL-C. However, dietary responses differed by LIPC genotype. In major allele carriers (CC/CT), HDL-C was higher following the Western diet compared with the Hispanic diet: (phase 1 (Western: 1.3 ± 0.03; Hispanic: 1.1 ± 0.04; P = 0.0004). Phase 2 (Western: 1.4.0 ± 0.03; Hispanic: 1.2 ± 0.03; P = 0.0003). In contrast, HDL-C in TT carriers did not differ by diet. In summary, major allele carriers benefited from the higher fat diet for HDL-C, while minor allele carriers did not. For LDL and total cholesterol, no significant interactions were observed between SNP and diet, but several differences by genotype were observed. In major allele carriers (CC/CT) but not in minor allele carriers, the Western diet was associated with higher LDL-C in phase 1 (Western: 2.9 ± 0.13; Hispanic: 2.5 ± 0.14; P = 0.025) and with higher total cholesterol in phase 1 (Western: 4.9 ± 0.14; Hispanic: 4.2 ± 0.14; P = 0.001) and phase 2 (Western: 5.0 ± 0.13; Hispanic: 4.6 ± 0.14; P = 0.018). Finally, we evaluated gene-diet interactions for TG. No significant interactions or difference by genotype were observed by diet for TG (P > 0.05; not shown).

Table 4.

Interaction between diet and LIPC for lipids at end of intervention diets

| C/C + C/T (n = 33) | T/T (n = 8) | P Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDL-C | |||

| Phase 1 | 0.203 | ||

| Hispanic diet | 1.1 (0.04) [43.9 (1.4)] | 1.3 (0.07) [50.0 (2.6)] | |

| Western diet | 1.3 (0.03) [51.1 (1.3)] | 1.3 (0.1) [50.9 (3.9)] | |

| P value | 0.0004 | 0.848 | |

| Phase 2 | 0.837 | ||

| Hispanic diet | 1.2 (0.03) [47.5 (1.2)] | 1.3 (0.09) [50.8 (3.4)] | |

| Western diet | 1.4 (0.03) [54.0 (1.3)] | 1.5 (0.06) [56.5 (2.4)] | |

| P value | 0.0003 | 0.166 | |

| LDL-C | |||

| Phase 1 | 0.453 | ||

| Hispanic diet | 2.5 (0.14) [95.8 (5.4)] | 2.7 (0.26) [105 (9.9)] | |

| Western diet | 2.9 (0.13) [112 (5.0)] | 3.5 (0.41) [137 (16.0)] | |

| P value | 0.025 | 0.099 | |

| Phase 2 | 0.812 | ||

| Hispanic diet | 2.8 (0.14) [109 (5.6)] | 2.8 (0.14) [98.8 (18.2)] | |

| Western diet | 3.1 (0.16) [119 (6.0)] | 3.1 (0.16) [103 (11.2)] | |

| P value | 0.198 | 0.823 | |

| Total Cholesterol | |||

| Phase 1 | 0.605 | ||

| Hispanic diet | 4.2 (0.16) [161 (6.0)] | 4.5 (0.28) [174 (11.0)] | |

| Western diet | 4.9 (0.14) [188 (5.6)] | 5.5 (0.46) [212 (17.7)] | |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.064 | |

| Phase 2 | 0.697 | ||

| Hispanic diet | 4.6 (0.13) [176 (4.9)] | 4.3 (0.39) [168 (15.2)] | |

| Western diet | 5.0 (0.14) [192 (5.2)] | 4.6 (0.25) [177 (9.8)] | |

| P value | 0.018 | 0.597 | |

Values are means (SE) in mmol/l [mg/dl]. Adjusted for age, sex, baseline waist circumference, and baseline lipid concentration. HDL-C was also adjusted for postdiet TG concentration. HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

We performed similar gene-diet interaction analyses for OGTT 2 h glucose (Table 5). For OGTT 2 h glucose, a dominant genetic model was used, based on published data for glycemic traits (27). We observed a marginally significant interaction for phase 1 (P interaction = 0.07). In phase 1, CC participants showed a lower glycemic response on the Hispanic diet (P = 0.04), while minor allele carriers (CT/TT) showed no difference. In contrast, CT/TT participants showed a lower glycemic response on the Western diet in phase 2 (P = 0.008). The SNP-diet interaction for OGTT in phase 2 was not significant.

Table 5.

Interaction between diet and LIPC for 2 h oral glucose tolerance test glucose concentration

| C/C (n = 16) | C/T + T/T (n = 25) | P Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | 0.071 | ||

| Hispanic diet | 4.4 (0.3) [80.1 (5.2)] | 5.0 (0.3) [89.2 (5.5)] | |

| Western diet | 5.5 (0.4) [99.2 (7.2)] | 4.9 (0.3) [88.3 (4.9)] | |

| P value | 0.038 | 0.891 | |

| Phase 2 | 0.308 | ||

| Hispanic diet | 4.9 (0.4) [89.0 (7.9)] | 5.3 (0.3) [96.2 (5.3)] | |

| Western diet | 4.5 (0.3) [80.4 (5.8)] | 4.2 (0.4) [75.3 (6.6)] | |

| P value | 0.376 | 0.008 |

Values are means (SE) in mmol/l [mg/dl]. Adjusted for age, sex, baseline waist circumference, and preload glucose.

Cross-sectional analysis of the BPRHS.

Finally, to extend analyses to a larger Caribbean Hispanic population, we tested LIPC SNP-diet interactions for HDL-C in the BPRHS (Table 6). The LIPC rs1800588 MAF was 0.31, and genotypes were consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. We limited analyses to a subset matched to the intervention for BMI (≤34 kg/m2) and without diabetes and applied the same recessive genetic model. We dichotomized total dietary fat intake into high and low, based on the median intake (% total energy), and observed no significant interaction. We next evaluated a sex-total fat interaction and observed a significant interaction (P = 0.036) for HDL-C. Due to the small number of men in the subset (10 with TT genotype, n = 5 men in each fat intake group), subsequent SNP-diet interaction analyses for dichotomized total fat (31%), SFA (9%), PUFA (7%), and MUFA (11%) were conducted only in women (n = 269; Table 6). Significant interactions for HDL-C were observed only for SFA (P interaction: 0.036; Table 6). Minor allele carriers (TT) had higher HDL-C (P = 0.038) with low SFA intake (1.5 ± 0.1 mmol/l) compared with high SFA intake (1.2 ± 0.1 mmol/l). No difference was observed for HDL-C in major allele carriers (CC/CT) by SFA intake. SNP-diet interactions were not observed for other types of fats.

Table 6.

Interaction between dietary fat and LIPC for HDL-C and TG in Boston Puerto Rican Health Study women

| HDL-C, mmol/l [mg/dl] |

TG, mmol/l [mg/dl] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C/C + C/T (n = 241) | T/T (n = 28) | P Interaction | C/C + C/T (n = 241) | T/T (n = 28) | P Interaction | |

| Total Fat | ||||||

| Low (<31% energy) | 1.3 (0.04) [50.7 (1.4)] | 1.4 (0.1) [55.9 (4.4)] | 0.532 | 1.6 (1.4, 1.8) [141.1 (127.7, 155.8)] | 1.8 (1.2, 2.3) [149.3 (108.4, 205.6)] | 0.523 |

| High (≥31% energy) | 1.3 (0.03) [49.8 (1.3)] | 1.3 (0.1) [51.4 (3.2)] | 1.4 (1.3, 1.6) [127.1 (115.3, 140.1)] | 1.7 (1.4, 2.2) [153.3 (121.9, 192.7)] | ||

| P | 0.605 | 0.406 | 0.097 | 0.902 | ||

| SFA | ||||||

| Low (<9% energy) | 1.3 (0.04) [50.0 (1.4)] | 1.5 (0.1) [58.0 (3.5)] | 0.036 | 1.7 (1.5–1.8) [147.6 (133.5, 163.1)] | 1.4 (1.3, 1.5) [127.8 (99.4, 164.4)] | 0.005 |

| High (≥9% energy) | 1.3 (0.03) [50.7 (1.3)] | 1.2 (0.1) [47.4 (3.7)] | 1.4 (1.1, 1.9) [121.8 (110.9, 133.8)] | 2.1 (2.6, 2.7) [183.1 (140.5, 238.7)] | ||

| P | 0.686 | 0.038 | 0.003 | 0.054 | ||

| PUFA | ||||||

| Low (<7% energy) | 1.3 (0.03) [50.5 (1.3)] | 1.4 (0.1) [54.0 (4.3)] | 0.858 | 1.5 (1.4, 1.7) [137.1 (124.4, 151)] | 1.7 (1.3, 2.4) [154.5 (111.6, 209.5)] | 0.871 |

| High (≥7% energy) | 1.3 (0.04) [49.9 (1.4)] | 1.4 (0.1) [52.4 (3.2)] | 1.5 (1.3, 1.6) [130.1 (118.1, 143.9)] | 1.7 (1.4, 2.2) [151.6 (119.7, 191.0)] | ||

| P | 0.718 | 0.759 | 0.421 | 0.924 | ||

| MUFA | ||||||

| Low (<11% energy) | 1.3 (0.03) [50.6 (1.3)] | 1.4 (0.1) [54.5 (4.2)] | 0.782 | 1.6 (1.4, 1.7) [140.6 (127.6, 154.8)] | 1.8 (1.3, 2.4) [126.5 (115.3, 213.2)] | 0.812 |

| High (≥11% energy) | 1.3 (0.04) [49.8 (1.4)] | 1.3 (0.1) [52.1 (3.3)] | 1.4 (1.3, 1.6) [126.5 (114.3, 140)] | 1.7 (1.3, 2.1) [149.3 (118, 188.8)] | ||

| P | 0.645 | 0.653 | 0.098 | 0.752 | ||

Values are means (SD) for HDL-C and geometric mean (95% CI) for TG. Limited to women without diabetes and BMI ≤34. Models are adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol status, total energy, waist circumference, physical activity and ancestral admixture. HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein; TG, triglyceride; SFA, saturated fatty acids; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acids.

In addition to HDL-C, we evaluated each type of fat (% total energy) in women without diabetes and BMI ≤34 for TG (Table 6). As for HDL-C, we observed a significant interaction term for SFA (P interaction: 0.005), with CC/CT individuals showing higher TG (P = 0.003) with low SFA intake [1.7 (95% confidence interval: 1.5, 1.8) mmol/l] compared with high SFA intake [1.4 (95% confidence interval: 1.1, 1.9) mmol/l]. In TT carriers, high SFA was marginally associated with higher TG. Interactions between LIPC genotype and dichotomized intakes of other fats for TG were not significant.

Finally, we evaluated each type of fat (% total energy) in women without diabetes and BMI ≤34 for total cholesterol and LDL-C (Table 7). No statistically significant interactions were identified for either of these outcomes.

Table 7.

Interaction between dietary fat and LIPC for TC and LDL-C in Boston Puerto Rican Health Study Women

| TC, mmol/l [mg/dl] |

LDL, mmol/l [mg/dl] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C/C + C/T (n = 241) | T/T (n = 28) | P Interaction | C/C + C/T (n = 241) | T/T (n = 28) | P Interaction | |

| Total Fat | ||||||

| Low (<31% energy) | 5.2 (0.1) [199.5 (4.1)] | 4.9 (0.3) [189.2 (13.2)] | 0.563 | 3 (0.09) [116.9 (3.5)] | 2.6 (0.3) [102.2 (11.1)] | 0.857 |

| High (≥31 energy) | 5.1 (0.1) [195.8 (4)] | 5.1 (0.2) [195.3 (9.4)] | 3.1 (0.09) [119 (3.4)] | 2.8 (0.2) [107 (8.2)] | ||

| P | 0.482 | 0.706 | 0.642 | 0.731 | ||

| SFA | ||||||

| Low (<9% energy) | 5.2 (0.1) [202.6 (4.2)] | 4.9 (0.3) [187.8 (10.5)] | 0.195 | 3.1 (0.1) [120.4 (3.6)] | 2.6 (0.2) [102 (8.9)] | 0.403 |

| High (≥9% energy) | 5 (0.1) [193.1 (4)] | 5.1 (0.3) [199.1 (11.1)] | 3 (0.1) [115.7 (3.4)] | 2.8 (0.3) [109 (9.8)] | ||

| P | 0.079 | 0.456 | 0.316 | 0.594 | ||

| PUFA | ||||||

| Low (<7% energy) | 5.2 (0.1) [202.5 (4)] | 5.2 (0.3) [202.9 (12.8)] | 0.753 | 3.1 (0.1) [121.3 (3.4)] | 3 (0.3) [116.6 (10.8)] | 0.431 |

| High (≥7% energy) | 5 (0.1) [192.4 (4.1)] | 4.9 (0.2) [187.6 (9.5)] | 3 (0.1) [114.1 (3.5)] | 2.5 (0.2) [98.2 (8.3)] | ||

| P | 0.056 | 0.336 | 0.111 | 0.177 | ||

| MUFA | ||||||

| Low (<11% energy) | 5.2 (0.1) [199.3 (4)] | 4.8 (0.3) [185 (12.5)] | 0.307 | 3 (0.1) [117.1 (3.4)] | 2.5 (0.3) [98.2 (10.6)] | 0.478 |

| High (≥11% energy) | 5.1 (0.1) [195.6 (4.2)] | 5.1 (0.3) [198.2 (9.7)] | 3.1 (0.1) [118.7 (3.6)] | 2.8 (0.2) [109.8 (8.5)] | ||

| P | 0.485 | 0.401 | 0.737 | 0.388 | ||

Values are means (SE). Limited to women without diabetes and BMI ≤34. Models are adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol status, total energy, waist circumference, physical activity, and ancestral admixture. LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein; TC, total cholesterol; SFA, saturated fatty acids; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acids.

DISCUSSION

Our investigation of dietary modulation of LIPC −514 C/T and cardiometabolic traits in a dietary intervention showed differences in dietary responses that depended on genotype. Specifically, while minor allele homozygotes (TT) did not demonstrate a reduction in HDL-C in response to higher fat intake, neither did they show the significant increase observed in major allele carriers (CC+CT). We did not detect a statistically significant gene-diet interaction, but the benefits derived from greater fat intake were limited to specific LIPC genotypes.

Previous studies provide evidence that this locus responds to dietary fat, although the designs and specific findings of the studies vary, and the mechanisms are not well understood. Two observational studies, the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) and Singapore Indians, demonstrated interactions between dietary fat intake and the variant, such that high fat intake was associated with higher HDL-C in major allele carriers, but with lower HDL-C in minor allele carriers (19, 25). Two interaction interventions confirmed this apparent sensitivity to dietary fat. One weight loss intervention showed that carriers of the minor (T) allele responded more to an intensive, lower fat (<30% energy) lifestyle intervention than to the usual care (9). In a second weight loss intervention that compared low-fat (20% total energy) and high-fat (40% total energy) diets, a difference in HDL-C by LIPC 514 C/T genotype was observed only in the low-fat group (31). In the current study, we expected that minor allele carriers would show lower HDL-C concentrations with the high-fat (Western) diet intervention. While there was no statistically significant gene-diet interaction, the high-fat diet increased HDL-C concentrations in major allele carriers but not in minor allele homozygotes. Evaluations of LDL-C and total cholesterol were similar to HDL-C, in that the Western diet caused statistically significant changes (increases) in major allele carriers but not minor allele homozygotes. Observations for all three lipids are consistent with previous evidence that higher-fat diets do not benefit LIPC minor allele carriers.

The lack of a significant SNP-diet interaction for HDL-C in the current intervention could be related to insufficient statistical power and could also be related to obesity-related complications, especially insulin resistance. Insulin increases hepatic lipase activity, and greater lipase activity reduces HDL-C (10, 20, 26). LIPC −514 C/T is associated with lower lipase activity and higher HDL-C, and the variant also interferes with insulin regulation of the lipase (3, 10). The combination of genetically determined loss of insulin responsiveness and obesity-related insulin resistance may obscure the detection of gene-diet interactions. Both a previous study (in which visceral obesity masked the association of LIPC 514 C/T with HDL-C) (24) and the current study support this hypothesis. Among intervention participants at baseline, the mean BMI in TT carriers approached obesity (BMI = 29.3 kg/m2) with waist circumference in the abdominally obese range (21). Obesity, which is often associated with lower HDL-C concentrations, may have prevented the genotype association with HDL-C from reaching statistical significance. Similarly, adiposity may have impaired the detection of SNP-diet interactions, by modulating HDL-C across all genotype categories.

Detection of SNP-diet interactions for OGTT could also have been obscured by insulin resistance. For OGTT, there was a marginally significant interaction between LIPC genotype and diet only for phase 1, in which the glucose concentration was higher with the Western diet compared with the Hispanic diet in CC individuals. There are several possible explanations for the lack of interaction in phase 2. First, we had some evidence that participants were more compliant to the diet during phase 1 than phase 2, which would maximize differences between the diets, to improve interaction detection. Second, the baseline diet for most participants was probably closer to the Western diet than the Hispanic diet (data not shown). For those whose phase 1 diet represented a shift from Western to Hispanic, genetically based differences in response to diet may have been more detectable, and these differences could have driven the marginal interaction seen in phase 1. By phase 2, when individuals were shifting from one intervention diet to the other, reduced compliance could have reduced actual differences between the diets, impairing our ability to detect interactions. However, these explanations remain speculative, particularly since no carryover effect was detected between diet phases.

Findings from the current intervention study and the BPRHS differed to some extent, and these differences could be related to design and sample size. Specifically, in the BPRHS the interactions between dietary fat and the SNP for HDL-C were consistent with earlier interaction analyses in FHS and Singapore Indians. In all three populations, high fat intake was detrimental for HDL-C concentration in minor allele carriers. In the dietary intervention, the interaction term for SNP × dietary pattern did not reach significance, but the higher fat (Western) diet was beneficial for HDL-C only in major allele carriers. One possibility is that large populations are needed to detect statistically significant gene-diet interactions, to minimize the impact of heterogeneity in individual responses. In addition, the dietary patterns differed not only in total fat, but also in fat composition (e.g., greater monounsaturated fatty acids in the Hispanic diet), which could also alter responses.

Intervention findings are strengthened by partial validation in the BPRHS, but limitations exist. Our confirmation of the LIPC SNP × diet interaction in the BPRHS and failure to reach interaction significance in the dietary intervention are likely related to insufficient statistical power in the intervention. The small number of TT individuals (n = 8, all women) and few men (n = 8) in the intervention precluded our ability to formally conduct sex-specific analyses, which is highly relevant to HDL-C. In addition, heterogeneity in the degree of insulin resistance among participants may have masked detection of gene-diet interactions. Although we excluded diabetes and severe obesity from both studies, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome rose between 2002 (the year of the Framingham LIPC study and 2011 (current intervention completion). This decline in US metabolic health, especially in susceptible ethnic minorities such as Hispanics, may impede the detection of gene-diet interactions (1, 7, 23).

In summary, findings from our gene-diet intervention supported but did not entirely confirm interaction patterns established in previous observational studies. Understanding of these inconsistencies is limited, but the differences are not surprising given the considerable variability in outcomes related to this locus. The current study illustrates the complexities and limitations of studying gene-diet interactions using different designs and at different historical time points. Future studies might be improved through more stringent control of variability in phenotypes that influence outcomes and may require larger sample sizes. Despite the challenges specific to LIPC, as well as those of gene-diet interactions overall, this study reinforces the need to consider genotype in dietary trials. Moreover, these findings highlight the critical importance of considering ethnicity in studies related to genetics, diet and cardiometabolic health.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants P01AG-023394, HL-54776, P50HL-105185, and DK-075030 and USDA contracts 53-K06-5-10 and 58-1950-9-001. C. E. Smith is supported by NIH Grant K08HL-112845.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.E.S. and M.I.V.R. analyzed data; C.E.S., M.I.V.R., J.M., and J.M.O. interpreted results of experiments; C.E.S. and M.I.V.R. drafted manuscript; C.E.S., M.I.V.R., J.M., J.F.G., B.G.-B., A.H.L., K.L.T., and J.M.O. edited and revised manuscript; C.E.S., M.I.V.R., J.M., J.F.G., B.G.-B., A.H.L., K.L.T., and J.M.O. approved final version of manuscript; M.I.V.R. prepared figures; J.M., A.H.L., K.L.T., and J.M.O. conceived and designed research; J.F.G. and B.G.-B. performed experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Trial registration: NCT02938091.

Current addresses: M. I. Van Rompay, New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA; J. Mattei, Dept. of Nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; B. Garcia-Bailo, Bell Inst. of Health and Nutrition, General Mills, Minneapolis, MN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar M, Bhuket T, Torres S, Liu B, Wong RJ. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2003-2012. JAMA 313: 1973–1974, 2015. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum SJ, Kris-Etherton PM, Willett WC, Lichtenstein AH, Rudel LL, Maki KC, Whelan J, Ramsden CE, Block RC. Fatty acids in cardiovascular health and disease: a comprehensive update. J Clin Lipidol 6: 216–234, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2012.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botma GJ, Verhoeven AJ, Jansen H. Hepatic lipase promoter activity is reduced by the C-480T and G-216A substitutions present in the common LIPC gene variant, and is increased by Upstream Stimulatory Factor. Atherosclerosis 154: 625–632, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(00)00478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corella D, Ordovas JM. Nutrigenomics in cardiovascular medicine. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2: 637–651, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.891366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Peloso GM, Gustafsson S, Kanoni S, Ganna A, Chen J, Buchkovich ML, Mora S, Beckmann JS, Bragg-Gresham JL, Chang HY, Demirkan A, Den Hertog HM, Do R, Donnelly LA, Ehret GB, Esko T, Feitosa MF, Ferreira T, Fischer K, Fontanillas P, Fraser RM, Freitag DF, Gurdasani D, Heikkilä K, Hyppönen E, Isaacs A, Jackson AU, Johansson Å, Johnson T, Kaakinen M, Kettunen J, Kleber ME, Li X, Luan J, Lyytikäinen LP, Magnusson PKE, Mangino M, Mihailov E, Montasser ME, Müller-Nurasyid M, Nolte IM, O’Connell JR, Palmer CD, Perola M, Petersen AK, Sanna S, Saxena R, Service SK, Shah S, Shungin D, Sidore C, Song C, Strawbridge RJ, Surakka I, Tanaka T, Teslovich TM, Thorleifsson G, Van den Herik EG, Voight BF, Volcik KA, Waite LL, Wong A, Wu Y, Zhang W, Absher D, Asiki G, Barroso I, Been LF, Bolton JL, Bonnycastle LL, Brambilla P, Burnett MS, Cesana G, Dimitriou M, Doney ASF, Döring A, Elliott P, Epstein SE, Ingi Eyjolfsson G, Gigante B, Goodarzi MO, Grallert H, Gravito ML, Groves CJ, Hallmans G, Hartikainen AL, Hayward C, Hernandez D, Hicks AA, Holm H, Hung YJ, Illig T, Jones MR, Kaleebu P, Kastelein JJP, Khaw KT, Kim E, Klopp N, Komulainen P, Kumari M, Langenberg C, Lehtimäki T, Lin SY, Lindström J, Loos RJF, Mach F, McArdle WL, Meisinger C, Mitchell BD, Müller G, Nagaraja R, Narisu N, Nieminen TVM, Nsubuga RN, Olafsson I, Ong KK, Palotie A, Papamarkou T, Pomilla C, Pouta A, Rader DJ, Reilly MP, Ridker PM, Rivadeneira F, Rudan I, Ruokonen A, Samani N, Scharnagl H, Seeley J, Silander K, Stančáková A, Stirrups K, Swift AJ, Tiret L, Uitterlinden AG, van Pelt LJ, Vedantam S, Wainwright N, Wijmenga C, Wild SH, Willemsen G, Wilsgaard T, Wilson JF, Young EH, Zhao JH, Adair LS, Arveiler D, Assimes TL, Bandinelli S, Bennett F, Bochud M, Boehm BO, Boomsma DI, Borecki IB, Bornstein SR, Bovet P, Burnier M, Campbell H, Chakravarti A, Chambers JC, Chen YI, Collins FS, Cooper RS, Danesh J, Dedoussis G, de Faire U, Feranil AB, Ferrières J, Ferrucci L, Freimer NB, Gieger C, Groop LC, Gudnason V, Gyllensten U, Hamsten A, Harris TB, Hingorani A, Hirschhorn JN, Hofman A, Hovingh GK, Hsiung CA, Humphries SE, Hunt SC, Hveem K, Iribarren C, Järvelin MR, Jula A, Kähönen M, Kaprio J, Kesäniemi A, Kivimaki M, Kooner JS, Koudstaal PJ, Krauss RM, Kuh D, Kuusisto J, Kyvik KO, Laakso M, Lakka TA, Lind L, Lindgren CM, Martin NG, März W, McCarthy MI, McKenzie CA, Meneton P, Metspalu A, Moilanen L, Morris AD, Munroe PB, Njølstad I, Pedersen NL, Power C, Pramstaller PP, Price JF, Psaty BM, Quertermous T, Rauramaa R, Saleheen D, Salomaa V, Sanghera DK, Saramies J, Schwarz PEH, Sheu WH, Shuldiner AR, Siegbahn A, Spector TD, Stefansson K, Strachan DP, Tayo BO, Tremoli E, Tuomilehto J, Uusitupa M, van Duijn CM, Vollenweider P, Wallentin L, Wareham NJ, Whitfield JB, Wolffenbuttel BHR, Ordovas JM, Boerwinkle E, Palmer CNA, Thorsteinsdottir U, Chasman DI, Rotter JI, Franks PW, Ripatti S, Cupples LA, Sandhu MS, Rich SS, Boehnke M, Deloukas P, Kathiresan S, Mohlke KL, Ingelsson E, Abecasis GR; Global Lipids Genetics Consortium . Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet 45: 1274–1283, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gómez P, Pérez-Jiménez F, Marín C, Moreno JA, Gómez MJ, Bellido C, Pérez-Martínez P, Fuentes F, Paniagua JA, López-Miranda J. The −514 C/T polymorphism in the hepatic lipase gene promoter is associated with insulin sensitivity in a healthy young population. J Mol Endocrinol 34: 331–338, 2005. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heiss G, Snyder ML, Teng Y, Schneiderman N, Llabre MM, Cowie C, Carnethon M, Kaplan R, Giachello A, Gallo L, Loehr L, Avilés-Santa L. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Hispanics/Latinos of diverse background: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Diabetes Care 37: 2391–2399, 2014. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodoglugil U, Williamson DW, Mahley RW. Polymorphisms in the hepatic lipase gene affect plasma HDL-cholesterol levels in a Turkish population. J Lipid Res 51: 422–430, 2010. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P001578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huggins GS, Papandonatos GD, Erar B, Belalcazar LM, Brautbar A, Ballantyne C, Kitabchi AE, Wagenknecht LE, Knowler WC, Pownall HJ, Wing RR, Peter I, McCaffery JM; Genetics Subgroup of the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) Study . Do genetic modifiers of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride levels also modify their response to a lifestyle intervention in the setting of obesity and type-2 diabetes mellitus?: The Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 6: 391–399, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansen H, Verhoeven AJ, Weeks L, Kastelein JJ, Halley DJ, van den Ouweland A, Jukema JW, Seidell JC, Birkenhäger JC. Common C-to-T substitution at position −480 of the hepatic lipase promoter associated with a lowered lipase activity in coronary artery disease patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 2837–2842, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.17.11.2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Junyent M, Tucker KL, Smith CE, Lane JM, Mattei J, Lai CQ, Parnell LD, Ordovás JM. The effects of ABCG5/G8 polymorphisms on HDL-cholesterol concentrations depend on ABCA1 genetic variants in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 20: 558–566, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krauss RM, Deckelbaum RJ, Ernst N, Fisher E, Howard BV, Knopp RH, Kotchen T, Lichtenstein AH, McGill HC, Pearson TA, Prewitt TE, Stone NJ, Horn LV, Weinberg R. Dietary guidelines for healthy American adults. A statement for health professionals from the Nutrition Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation 94: 1795–1800, 1996. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.7.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai CQ, Tucker KL, Choudhry S, Parnell LD, Mattei J, García-Bailo B, Beckman K, Burchard EG, Ordovás JM. Population admixture associated with disease prevalence in the Boston Puerto Rican health study. Hum Genet 125: 199–209, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0612-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, Franch HA, Franklin B, Kris-Etherton P, Harris WS, Howard B, Karanja N, Lefevre M, Rudel L, Sacks F, Van Horn L, Winston M, Wylie-Rosett J. Summary of American Heart Association Diet and Lifestyle Recommendations revision 2006. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 2186–2191, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000238352.25222.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma Y, Tucker KL, Smith CE, Lee YC, Huang T, Richardson K, Parnell LD, Lai CQ, Young KL, Justice AE, Shao Y, North KE, Ordovás JM. Lipoprotein lipase variants interact with polyunsaturated fatty acids for obesity traits in women: replication in two populations. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 24: 1323–1329, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattei J, Demissie S, Tucker KL, Ordovás JM. The APOA1/C3/A4/A5 cluster and markers of allostatic load in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 21: 862–870, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D. CONSORT: an evolving tool to help improve the quality of reports of randomized controlled trials. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials. JAMA 279: 1489–1491, 1998. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noel SE, Lai C-Q, Mattei J, Parnell LD, Ordovas JM, Tucker KL. Variants of the CD36 gene and metabolic syndrome in Boston Puerto Rican adults. Atherosclerosis 211: 210–215, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ordovás JM, Corella D, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Couture P, Coltell O, Wilson PW, Schaefer EJ, Tucker KL. Dietary fat intake determines the effect of a common polymorphism in the hepatic lipase gene promoter on high-density lipoprotein metabolism: evidence of a strong dose effect in this gene-nutrient interaction in the Framingham Study. Circulation 106: 2315–2321, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000036597.52291.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pihlajamäki J, Karjalainen L, Karhapää P, Vauhkonen I, Taskinen MR, Deeb SS, Laakso M. G-250A substitution in promoter of hepatic lipase gene is associated with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance in healthy control subjects and in members of families with familial combined hyperlipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 1789–1795, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.20.7.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi Q, Strizich G, Hanna DB, Giacinto RE, Castañeda SF, Sotres-Alvarez D, Pirzada A, Llabre MM, Schneiderman N, Avilés-Santa LM, Kaplan RC. Comparing measures of overall and central obesity in relation to cardiometabolic risk factors among US Hispanic/Latino adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23: 1920–1928, 2015. doi: 10.1002/oby.21176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santamarina-Fojo S, González-Navarro H, Freeman L, Wagner E, Nong Z. Hepatic lipase, lipoprotein metabolism, and atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1750–1754, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000140818.00570.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneiderman N, Llabre M, Cowie CC, Barnhart J, Carnethon M, Gallo LC, Giachello AL, Heiss G, Kaplan RC, LaVange LM, Teng Y, Villa-Caballero L, Avilés-Santa ML. Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics/Latinos from diverse backgrounds: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Diabetes Care 37: 2233–2239, 2014. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.St-Pierre J, Miller-Felix I, Paradis ME, Bergeron J, Lamarche B, Després JP, Gaudet D, Vohl MC. Visceral obesity attenuates the effect of the hepatic lipase -514C>T polymorphism on plasma HDL-cholesterol levels in French-Canadian men. Mol Genet Metab 78: 31–36, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7192(02)00223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tai ES, Corella D, Deurenberg-Yap M, Cutter J, Chew SK, Tan CE, Ordovas JM; Singapore National Health Survey . Dietary fat interacts with the −514C>T polymorphism in the hepatic lipase gene promoter on plasma lipid profiles in a multiethnic Asian population: the 1998 Singapore National Health Survey. J Nutr 133: 3399–3408, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teran-Garcia M, Santoro N, Rankinen T, Bergeron J, Rice T, Leon AS, Rao DC, Skinner JS, Bergman RN, Després JP, Bouchard C; HERITAGE Family Study . Hepatic lipase gene variant −514C>T is associated with lipoprotein and insulin sensitivity response to regular exercise: the HERITAGE Family Study. Diabetes 54: 2251–2255, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, Pirruccello JP, Ripatti S, Chasman DI, Willer CJ, Johansen CT, Fouchier SW, Isaacs A, Peloso GM, Barbalic M, Ricketts SL, Bis JC, Aulchenko YS, Thorleifsson G, Feitosa MF, Chambers J, Orho-Melander M, Melander O, Johnson T, Li X, Guo X, Li M, Shin Cho Y, Jin Go M, Jin Kim Y, Lee JY, Park T, Kim K, Sim X, Twee-Hee Ong R, Croteau-Chonka DC, Lange LA, Smith JD, Song K, Hua Zhao J, Yuan X, Luan J, Lamina C, Ziegler A, Zhang W, Zee RY, Wright AF, Witteman JC, Wilson JF, Willemsen G, Wichmann HE, Whitfield JB, Waterworth DM, Wareham NJ, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Voight BF, Vitart V, Uitterlinden AG, Uda M, Tuomilehto J, Thompson JR, Tanaka T, Surakka I, Stringham HM, Spector TD, Soranzo N, Smit JH, Sinisalo J, Silander K, Sijbrands EJ, Scuteri A, Scott J, Schlessinger D, Sanna S, Salomaa V, Saharinen J, Sabatti C, Ruokonen A, Rudan I, Rose LM, Roberts R, Rieder M, Psaty BM, Pramstaller PP, Pichler I, Perola M, Penninx BW, Pedersen NL, Pattaro C, Parker AN, Pare G, Oostra BA, O’Donnell CJ, Nieminen MS, Nickerson DA, Montgomery GW, Meitinger T, McPherson R, McCarthy MI, McArdle W, Masson D, Martin NG, Marroni F, Mangino M, Magnusson PK, Lucas G, Luben R, Loos RJ, Lokki ML, Lettre G, Langenberg C, Launer LJ, Lakatta EG, Laaksonen R, Kyvik KO, Kronenberg F, König IR, Khaw KT, Kaprio J, Kaplan LM, Johansson A, Jarvelin MR, Janssens AC, Ingelsson E, Igl W, Kees Hovingh G, Hottenga JJ, Hofman A, Hicks AA, Hengstenberg C, Heid IM, Hayward C, Havulinna AS, Hastie ND, Harris TB, Haritunians T, Hall AS, Gyllensten U, Guiducci C, Groop LC, Gonzalez E, Gieger C, Freimer NB, Ferrucci L, Erdmann J, Elliott P, Ejebe KG, Döring A, Dominiczak AF, Demissie S, Deloukas P, de Geus EJ, de Faire U, Crawford G, Collins FS, Chen YD, Caulfield MJ, Campbell H, Burtt NP, Bonnycastle LL, Boomsma DI, Boekholdt SM, Bergman RN, Barroso I, Bandinelli S, Ballantyne CM, Assimes TL, Quertermous T, Altshuler D, Seielstad M, Wong TY, Tai ES, Feranil AB, Kuzawa CW, Adair LS, Taylor HA Jr, Borecki IB, Gabriel SB, Wilson JG, Holm H, Thorsteinsdottir U, Gudnason V, Krauss RM, Mohlke KL, Ordovas JM, Munroe PB, Kooner JS, Tall AR, Hegele RA, Kastelein JJ, Schadt EE, Rotter JI, Boerwinkle E, Strachan DP, Mooser V, Stefansson K, Reilly MP, Samani NJ, Schunkert H, Cupples LA, Sandhu MS, Ridker PM, Rader DJ, van Duijn CM, Peltonen L, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M, Kathiresan S. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 466: 707–713, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tucker KL, Mattei J, Noel SE, Collado BM, Mendez J, Nelson J, Griffith J, Ordovas JM, Falcon LM. The Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort study on health disparities in Puerto Rican adults: challenges and opportunities. BMC Public Health 10: 107, 2010. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner-McGrievy G, Harris M. Key elements of plant-based diets associated with reduced risk of metabolic syndrome. Curr Diab Rep 14: 524, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0524-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waterworth DM, Jansen H, Nicaud V, Humphries SE, Talmud PJ; EARSII Study Group . Interaction between insulin (VNTR) and hepatic lipase (LIPC−514C>T) variants on the response to an oral glucose tolerance test in the EARSII group of young healthy men. Biochim Biophys Acta 1740: 375–381, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu M, Ng SS, Bray GA, Ryan DH, Sacks FM, Ning G, Qi L. Dietary Fat Intake Modifies the Effect of a Common Variant in the LIPC Gene on Changes in Serum Lipid Concentrations during a Long-Term Weight-Loss Intervention Trial. J Nutr 145: 1289–1294, 2015. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.212514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yabu Y, Noma K, Nakatani K, Nishioka J, Suematsu M, Katsuki A, Hori Y, Yano Y, Sumida Y, Wada H, Nobori T. C−514T polymorphism in hepatic lipase gene promoter is associated with elevated triglyceride levels and decreasing insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic Japanese subjects. Int J Mol Med 16: 421–425, 2005. 10.3892/ijmm.16.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zambon A, Bertocco S, Vitturi N, Polentarutti V, Vianello D, Crepaldi G. Relevance of hepatic lipase to the metabolism of triacylglycerol-rich lipoproteins. Biochem Soc Trans 31: 1070–1074, 2003. doi: 10.1042/bst0311070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zivkovic AM, German JB, Sanyal AJ. Comparative review of diets for the metabolic syndrome: implications for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Clin Nutr 86: 285–300, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]