Abstract

Genetic testing has multiple clinical applications including disease risk assessment, diagnosis, and pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics can be utilized to predict whether a pharmacologic therapy will be effective or to identify patients at risk for treatment-related toxicity. Although genetic tests are typically ordered for a distinct clinical purpose, the genetic variants that are found may have additional implications for either disease or pharmacology. This review will address multiple examples of germline genetic variants that are informative for both disease and pharmacogenomics. The discussed relationships are diverse. Some of the agents are targeted for the disease-causing genetic variant, while others, although not targeted therapies, have implications for the disease they are used to treat. It is also possible that the disease implications of a genetic variant are unrelated to the pharmacogenomic implications. Some of these examples are considered clinically actionable pharmacogenes, with evidence-based, pharmacologic treatment recommendations, while others are still investigative as areas for additional research. It is important that clinicians are aware of both the disease and pharmacogenomic associations of these germline genetic variants to ensure patients are receiving comprehensive personalized care.

Keywords: pharmacogenomics, pharmacogenetics, genetics, disease genetics, CFTR, BRCA, UGT1A1, G6PD, RYR1, INFL3, CMT genes, ADBR1, COMT

integration of patient genetic information into clinical practice has many possible benefits and implications. Genetic information can help identify the risk for developing a disease, which can inform future patient screening, monitoring, or prevention, or it can be diagnostic with implications for disease prognosis. Utilization of this information can allow for personalization of the patient treatment plan to optimize treatment goals. Genetic information can also inform clinicians about the likelihood of treatment efficacy or safety with pharmacologic interventions. Pharmacogenomics, the study of how genetic variation contributes to differences in treatment outcomes, allows clinicians to identify and apply these relationships. Although pharmacogenomics is a distinct field, there is substantial overlap in the genes that are responsible for disease risk, disease prognosis, and pharmacologic treatment response. Consequently, a genetic test ordered for a disease evaluation may have additional clinical implications for a pharmacologic treatment the patient may receive. As utilization of targeted multigene panel testing or next-generation sequencing becomes more common, it is likely that more incidental genetic information will be reported. Incidental findings can occur for both disease and pharmacogenetic tests and may have clinical implications over the patient’s lifetime even if they’re not informative for the specific reason the test was ordered. An important caveat to pharmacogenetic interpretation of genetic results, particularly for drug-metabolizing enzymes, is that the genetic variation on both alleles must be considered to identify the clinically relevant phenotype.

The objective of this review is to describe examples of germline genetic variants that have clinical implications for both diseases and pharmacogenomics. The genetic relationships we describe, summarized in Table 1, highlight the diversity of these associations, with each representing a unique interaction between patient genetics, disease occurrence and risk or severity, and drug clearance or response. In the first section of this review we will discuss genes with clinically actionable pharmacogenomic implications, as defined by the existence of evidence-based treatment guidelines. In the second part of the review we will evaluate some pharmacogenomic discoveries that are not yet actionable but represent potential areas for further investigations. There is considerable diversity in the genetic and pharmacogenomic relationships. In some cases, the genetic variation has implications for the disease and the selection of a targeted agent for treating that disease. In other cases, the drug is not targeted for the genetic variant but is involved in the management of the disease it affects, and the pharmacodynamics of the drug are altered because of the variant, resulting in reduced efficacy or enhanced toxicity. Additionally, we discuss examples in which the genetic variant is associated with disease occurrence and a completely unrelated pharmacologic treatment outcome. As genetic information becomes more abundant, it is important that clinicians recognize both the disease and pharmacogenomic implications of this information to optimize patient care.

Table 1.

Summary of reviewed genes and their respective disease and pharmacologic implications

| Strength of Pharmacogenetic Evidence | Gene | Disease Implications | Drug or Drug Class | Therapeutic Implication | Pharmacogenetic Guideline | FDA Biomarker on Drug Labeling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinically actionable pharmacogenes | CFTR | cystic fibrosis | ivacaftor | treatment efficacy | yes* | yes |

| lumacaftor | treatment efficacy | no | yes | |||

| BRCA | breast and ovarian cancer risk | PARP inhibitors | treatment efficacy | no | yes | |

| UGT1A1 | Crigler Najjar and Gilbert’s syndrome | irinotecan | neutropenia | yes†‡ | yes | |

| atazanavir | hyperbilirubinemia | yes* | yes | |||

| G6PD | G6PD deficiency | rasburicase | acute hemolytic anemia and methemoglobinemia | yes* | yes | |

| RYR1 | malignant hyperthermia predisposition | inhaled anesthetics | malignant hyperthermia | no§ | yes (sevoflurane) | |

| INFL3 | hepatitis C spontaneous clearance | PEG interferon-α | treatment efficacy | yes* | no | |

| Investigational pharmacogenes | CMT genes | hereditary neuropathy | taxanes | neurotoxicity | no | no |

| ADBR1 | hypertension, heart failure | Β-blockers | treatment efficacy | no | no | |

| COMT | schizophrenia | antipsychotics | treatment efficacy | no | no | |

| depression | antidepressants | treatment efficacy | no | no | ||

| pain | opioids | treatment efficacy | no | no |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; PEG, pegylated; CMT, Charcot Marie Tooth.

Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guideline;

Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group guideline;

French National Network of Pharmacogenetics guideline (RNPGx);

CPIC level of evidence: A, clinically actionable.

CLINICALLY ACTIONABLE PHARMACOGENES

Targeted Therapies

One of the areas of personalized medicine with the most research is in the development of targeted therapies. Treatment efficacy for these agents is often dependent on the presence or absence of specific genetic variation, and pharmacogenetic testing is required before prescribing these targeted therapies. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling reports over 100 agents with genetic information in the approved labeling (107). The majority of the targeted agents included in this table are cancer therapies targeted for somatic mutations not germline variants, which are beyond the scope of this review. However, there are also targeted oncology therapies that consider germline genetic information and targeted therapies for noncancer diseases such as cystic fibrosis; this section will discuss these agents.

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane receptor.

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane receptor (CFTR) is an anion channel that plays an essential role in fluid regulation across the epithelium, encoded by the CFTR gene (171). CFTR facilitates the secretion of chloride ions (Cl−) and bicarbonate (), which leads to passive secretion of sodium (Na+) and water. Therefore, impairment of CFTR activity results in a reduction of water secretion across the epithelium (171). Cystic fibrosis is caused by genetic variations in the CFTR gene. Thousands of genetic variations in CFTR have been identified, and over 200 of those variants have been annotated as causative for cystic fibrosis (3, 4). The disease manifests predominantly with respiratory and pancreatic dysfunction due to the high expression of CFTR in these tissues. The severity of the disease can vary based on the underlying severity of the CFTR dysfunction (171). CFTR genetic variations were originally categorized into classes based on the functional consequences of the variant, but reclassifications have recently been proposed based on the development of potential targeted therapies (56, 135, 225). Class I, II, and III variants have more severe disease phenotypes, as the variants result in greater impairment to CFTR function (56, 135).

Ivacaftor is a potentiator of CFTR, increasing the probability the channel will be open and allow secretion of Cl− (65). The ability to potentiate the opening of CFTR is dependent on the presence of CFTR in the plasma membrane, so ivacaftor therapy is not efficacious for all classes of CFTR variants. Class III variants are characterized by impaired gating of the channel and are found in ~5% of cystic fibrosis patients. Ivacaftor represents an efficacious treatment option for this subset of patients and is FDA approved for over 30 CFTR variants, as listed in Table 2. In patients with these variants, ivacaftor significantly reduced sweat chloride concentration, either in vitro or in patients, demonstrating the ability to increase the open channel for Cl− secretion (57, 208). Ivacaftor has also been shown to improve lung function and weight gain, as well as significantly improve patient reported outcomes according to Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised scores (57, 76, 91, 156, 195).

Table 2.

Variants targeted by CFTR directed therapies

| Drug Therapy | CFTR Class | Functional Defect | Variant(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ataluren (48) | I | no synthesis | Nonsense mutations such as: G542X |

| Lumacaftor | II | impaired processing | Homozygous for F508del |

| Ivacaftor | II, III (210) | impaired processing and altered regulation/gating | A1067T |

| D1270N | |||

| D579G | |||

| E56K | |||

| D110H | |||

| F1074L | |||

| L206W | |||

| P67L | |||

| R1070Q | |||

| R1070W | |||

| R117C | |||

| R74W | |||

| S945L | |||

| S977F | |||

| A455E | |||

| III (210) | altered regulation or gating | G551D | |

| G178R | |||

| S549N | |||

| S549R | |||

| G551S | |||

| G1244E | |||

| S1251N | |||

| S1255P | |||

| G1349D | |||

| D110E | |||

| D1152H | |||

| E193K | |||

| F1052V | |||

| G1069R | |||

| K1060T | |||

| R347H | |||

| R352Q | |||

| IV | impaired conductance | R117H | |

| Tezacaftor (49, 50) | II | impaired processing | F508del |

The most common causative variant for cystic fibrosis is the F580del, which is identified in up to 80% of patients with cystic fibrosis (184). The F580del variant results in CFTR misfolding and instability, so very little protein is transported to the plasma membrane. The protein that is located in the membrane is not stable. This variant can therefore be categorized into more than one CFTR variant class (62). Ivacaftor requires CFTR be present in the membrane for efficacy, but because the F508del causes very little protein to reach the membrane the drug is unable to meaningfully stimulate the function of protein. Patients with the F580del variant are therefore not responsive to ivacaftor alone (72). The combination of lumacaftor with ivacaftor is approved for the treatment of cystic fibrosis in patients who are homozygous for the F580del variant. Lumacaftor is a CFTR corrector that increases the amount of CFTR found in the plasma membrane and improves protein folding in cells with F508del (207). Treatment with lumacaftor and ivacaftor improves pulmonary function and weight gain compared with placebo (211). Additional targeted therapies are currently under investigation for the treatment of cystic fibrosis, including the CFTR corrector tezacaftor (VX-661) (49, 50) and the CFTR read-through agent, ataluren, which has shown preclinical potential for the treatment of cystic fibrosis caused by the class I mutation G542X (48, 215).

BRCA.

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are renowned in their role in predisposing patients to breast cancer in addition to ovarian cancer and other tumor types. The discovery that breast cancer is inherited dates back to the 1980s (145), with the BRCA genes being identified in the ensuing decade (138, 218). An estimated 0.2–0.3% of the general population carries deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2, but these rates increase to 3 and 10% in patients with breast and ovarian cancer, respectively, and are much greater in families with hereditary cancer syndromes (144). The best-established deleterious mutations are highly penetrant, with lifetime risk of breast and ovarian cancer in excess of 40% in patients carrying these deleterious variants (144). Most of the validated deleterious variants are genetic insertions or deletions that cause an early stop-codon and produce a nonfunctional truncated protein. However, many other types of genetic aberrations have been identified, including splice site alterations and missense mutations (35), in addition to thousands of variants of unknown significance identified in families with cancer syndromes (64, 80). The increased risk of cancer in patients with deleterious BRCA variants is attributed to the role of BRCA proteins in homologous recombination, a process for repairing double-strand DNA breaks. The loss of homologous recombination decreases DNA replication fidelity, increasing the introduction of genetic variants that can activate oncogenes or inactivate tumor suppressor genes, leading to oncogenesis. Based on the frequency and penetrance of these deleterious variants, genetic screening is widely available for patients with familial breast cancer (90), though the optimal population to screen is an area of ongoing debate (24).

In addition to the established role of BRCA deficiency in cancer development, the tumor’s BRCA deficiency has been leveraged as a target for drug therapy. Tumor cells with BRCA deficiency lack the machinery for homologous recombination, one process for DNA repair, making them exquisitely sensitive to drugs that target compensatory mechanisms of DNA repair (127). Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 and 2 (PARP1 and PARP2) are enzymes that bind to and fix single-strand DNA breaks via base-excision repair (63, 172). Though there is some debate regarding the exact mechanism for this synergy (84), referred to as “synthetic lethality,” the effectiveness of PARP inhibition in BRCA-deficient tumors is well established in preclinical models (41) and in clinical trials (73). Several PARP inhibitors have been developed for BRCA-deficient tumors, including the FDA-approved olaparib (115) and rucaparib (106), and talazoparib, a second-generation PARP inhibitor currently in development (58). These approvals and trials vary in their definition of BRCA-deficient tumors. Olaparib is approved only for patients with “deleterious or suspected deleterious” germline variants (100), whereas recent clinical studies have enrolled patients with germline or somatic deleterious variants or tumors that have BRCAness phenotype, regardless of the existence of a BRCA variant (191).

Pharmacokinetic Interactions

In addition to disease implications, genetic variants in enzymes or transporters can cause altered drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and/or excretion. These pharmacokinetic changes can have implications for drug efficacy and toxicity. Both of the pharmacokinetic pharmacogenetic interactions described below have associations with drug toxicity.

UGT1A1.

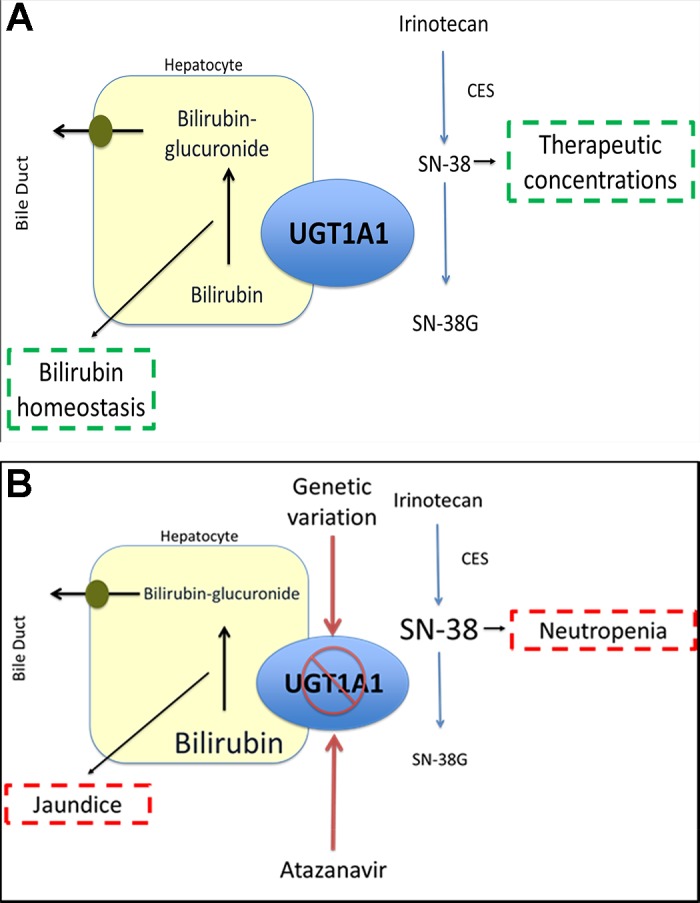

UGT1A1 is a hepatic enzyme that is responsible for the glucuronidation of bilirubin, as shown in Fig. 1A (38). Genetic variants in UGT1A1 that cause impaired enzyme activity can result in multiple disorders of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, including Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 (CN1) and type 2 (CN2) and Gilbert’s disease. CN1 is a severe disease phenotype, which is often fatal in infancy, due to the extreme bilirubin elevation and risk for developing kernicterus, brain damage associated with hyperbilirubinemia, with limited management strategies other than liver transplant (54, 55, 176, 188). CN2 is a moderate disease phenotype, characterized by elevated serum bilirubin concentrations and jaundice, which can be managed with phenobarbital (19, 92, 203). Gilbert’s syndrome is a mild phenotype that results in mild, intermittent jaundice and does not require treatment (18). To date, over 100 genetic variants in UGT1A1 have been identified that are diagnostic of CN1, CN2, and Gilbert’s syndrome (43, 121, 136, 198). The majority of these variants are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) resulting in missense or nonsense mutations (43). The genetic variants lead to varying degrees of impairment of UGT1A1 activity, and the severity of the enzyme impairment is associated with disease severity. CN1 causative variants result in the complete loss of UGT1A1 activity; CN2 causative variants have some residual UGT1A1 activity, whereas Gilbert’s syndrome variants are characterized by a moderate reduction in UGT1A1 activity as described in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

Role of UGT1A1 in bilirubin and irinotecan glucuronidation and impact of genetic variation. A: in individuals not carrying genetic variants that decrease UGT1A1 activity, the enzyme maintains homeostatic regulation of bilirubin and inactivates SN-38, the active metabolite irinotecan via glucuronidation. This patient experiences neither hyperbilirubinemia or high risk of irinotecan toxicity. B: reduced activity of UGT1A1 secondary to genetic variation results in a reduction in the glucuronidation of bilirubin, increasing the concentration of unconjugated bilirubin, and leading to an increased likelihood for jaundice or other clinical manifestations of hyperbilirubinemia. Atazanavir, a UGT1A1 inhibitor, also reduces UGT1A1 activity, increasing the likelihood for hyperbilirubinemia, especially in individuals who also carry genetic variants of UGT1A1. Reduced activity of UGT1A1 decreases the glucuronidation of SN-38, increasing the systemic concentrations of this active metabolite, which increases the risk of irinotecan toxicity primarily manifesting as neutropenia.

Table 3.

Examples of UGT1A1 genetic variants associated with Crigler-Najjar and Gilbert’s syndrome

| Syndrome | Approximate % of Normal UGT1A1 Activity | Example Genotypes |

|---|---|---|

| CN1 (37) | 0 | Q331X |

| S376Frameshift | ||

| CN2 | 0–7.6 | L15R (178) |

| Y486D (219) | ||

| Gilbert’s syndrome | 32–45 (93) | TATA repeat (*28, 36) |

| G71R (*6, 219) |

Approximate % of normal UGT1A1 activity is the percent activity reported for homozygous expression of the variants. CN1, Crigler-Najjar type 1; CN2: Crigler-Najjar type 2.

Atazanavir is a protease inhibitor that prevents human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) viral replication by inhibiting the processing of Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins required for virion formation (13). Atazanavir is an inhibitor of CYP3A4, CYP2C8, and UGT1A1 (13, 221). Hyperbilirubinemia is the most commonly reported adverse event with atazanavir therapy, secondary to the inhibition of UGT1A1. In clinical trials involving atazanavir, grade 3–4 hyperbilirubinemia occurred in 22–47% of patients, and ~10% of these individuals experienced symptomatic jaundice or scleral icterus (13).

All patients who receive atazanavir will experience a reduction in UGT1A1 enzyme activity and consequent increases in serum bilirubin concentrations (110). Individuals with impaired UGT1A1 activity are at an increased risk of experiencing clinically significant, symptomatic hyperbilirubinemia with the administration of atazanavir, highlighted in Fig. 1B (20, 71). UGT1A1 poor metabolizers (homozygotes or compound heterozygotes for UGT1A1*28 or UGT1A1*6) have the highest likelihood of experiencing grade 3–4 hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice and were significantly more likely to discontinue atazanavir therapy due to toxicity (66, 151, 165, 166, 168, 209). The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) recommends avoiding atazanavir use in UGT1A1 poor metabolizers secondary to the increased risk of symptomatic hyperbilirubinemia and discontinuation of therapy (74).

Atazanavir combination regimens were recently downgraded from preferred to alternative regimens for adult HIV treatment based on concerns regarding hyperbilirubinemia (8, 118). Application of UGT1A1 genetic information could be utilized to identify patients who are at elevated risk of hyperbilirubinemia, for selection of alternative medication, while atazanavir remains a viable treatment option for patients with lower risk.

Irinotecan, a topoisomerase inhibitor, is utilized first line as combination therapy for colorectal cancer and other solid organ malignancies (28) (196). Irinotecan is a prodrug that is converted to active SN-38 via carboxylesterases. SN-38 prevents the repair of single-strand DNA breaks by binding to topoisomerase I (2). SN-38 is inactivated to SN-38-glucuronide (SN-38G) via UGT1A1. The most common dose-limiting toxicities associated with irinotecan therapy are diarrhea and neutropenia (2, 154).

Individuals with reduced UGT1A1 activity have higher SN-38 exposure, as highlighted in Fig. 1B (16, 93, 95, 153). Higher SN-38 exposure has been correlated with the risk of developing neutropenia (159, 173). The association between UGT1A1 genotype and irinotecan toxicity appears to be dependent on irinotecan dose, with an increased risk for clinically significant toxicity at increasing doses of irinotecan. Treatment guidelines providing genotype-based dose adjustments for irinotecan have been published by the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group and the French National Network of Pharmacogenetics (155, 190). The FDA package insert also provides a warning that UGT1A1 poor metabolizers are at an increased risk for developing neutropenia and recommends empirically reducing the irinotecan dose by one dosing level in these patients (2).

UGT1A1 genotype has also been implicated as a prognostic marker for irinotecan therapy in colorectal cancer. Some studies have suggested a survival benefit in patients who were UGT1A1 poor metabolizers (200), although this association has been inconsistently reported (60, 120, 124). The improved response has been attributed to the higher SN-38 concentrations in these patients (42). Subsequent pharmacokinetic evaluations have identified that patients who are not UGT1A1 poor metabolizers can tolerate significantly higher doses of irinotecan than are currently recommended in clinical practice (101, 133, 201). This suggests patients without impaired UGT1A1 activity may not be achieving the necessary SN-38 concentrations for maximal treatment efficacy with standard doses. Prospective studies are currently underway to determine whether treatment outcomes can be improved by utilizing genotype-guided dosing strategies that increase irinotecan doses in these patients (32, 128, 220).

Glucose-6-phosphase dehydrogenase.

Glucose-6-phosphase dehydrogenase (G6PD) is an enzyme involved in the pentose pathway that is responsible for the oxidation of glucose-6-phosphate and ultimately results in the formation of NADPH (129). G6PD is the only enzyme that produces NADPH in red blood cells (RBCs), and a deficiency in G6PD can lead to an inability of RBCs to manage conditions of oxidative stress. Under conditions of stress, glutathione, which requires NADPH for activation, removes reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the cell. In G6PD-deficient RBCs the capacity to reduce glutathione is limited, because of the reduced capacity of G6PD to form NADPH, and the ROS can lead to cell lysis (129). G6PD deficiency is caused by genetic variation of G6PD. Over 150 genetic variants in G6PD have been reported in the literature, and variants have been categorized into classes based on phenotypic severity by the World Health Organization (7, 139). G6PD deficiency is most commonly found in individuals who hail from areas that are endemic to malaria, as genetic variation in G6PD is protective against malarial infection by reducing Plasmodium replication (223).

G6PD is located on the X chromosome, so phenotypic interpretation of the genetic variation differs for men and women. As men are hemizygous for G6PD, the phenotype in men can be determined based on the presence or absence of a variant. G6PD phenotype in women is more complicated, as women exhibit genetic mosaicism, where only one X chromosome is expressed in each cell (30). It is therefore not always possible to determine the G6PD activity in women by genotype alone, as there is no way to know the proportion of expression of each allele without phenotypic testing. Most individuals with G6PD deficiency are asymptomatic; however, the most severe G6PD variants are characterized by chronic nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia (CNSHA) without a precipitating event (7). The hemolysis of RBC can also result in acute episodes of jaundice from increased serum bilirubin, especially in individuals who both are G6PD deficient and have decreased function UGT1A1 variants (97).

Acute hemolytic anemia or methemoglobinemia are the most common manifestations of non-CNSHA G6PD deficiency and occur upon exposure to substances that increase ROS. Fava beans were the first substance identified that precipitated this response in G6PD-deficient individuals (192, 193). Subsequently, over 20 agents have warnings for G6PD deficiency included in the drug labeling (107), and a list of over 80 drug therapies associated with hemolytic anemia in G6PD-deficient individuals is maintained by the G6PD deficiency association (5, 107). G6PD deficiency is a contraindication for the use of the recombinant urate oxidase agents, rasburicase and pegloticase (6, 9). These agents convert uric acid to allantoin and, in the process, release H2O2, a ROS. Many cases of acute hemolytic anemia and methemoglobinemia, some of which were fatal, have been reported in patients with unknown G6PD deficiency at the time of drug administration (33, 99, 149, 150). Clinical guidelines for the use of G6PD genetic information in regards to rasburicase use have been published by CPIC, and future guideline updates anticipate inclusion of additional agents with pharmacogenetic associations with G6PD (164).

Pharmacodynamic Interactions

The pharmacodynamics or the physiological response to drug therapy can also be altered by disease-causing genetic variants. Physiologically, the site of action for the agent of interest may be altered, or there may be a deviation in a downstream effect to the drug binding to the site of action. The genetic variants that have pharmacodynamic implications can be associated with either drug efficacy or drug toxicity.

Ryanodine receptor isoform 1.

Ryanodine receptor isoform 1 (RYR1) is involved in the regulation of calcium ions (Ca2+), and the opening of RYR1 releases calcium to initiate muscular contraction (14). RYR1 is located in multiple tissues but is the predominant RYR isoform in skeletal muscle (111, 112). Hundreds of RYR1 genetic variations have been identified, although only a minority have been associated with the development of common core disease (187), risk for developing malignant hyperthermia, exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis, and other musculoskeletal disorders (14, 111). The variants associated with development of malignant hyperthermia have been previously described and are updated on the European Malignant Hyperthermia Group webpage (77, 187). The proposed putative mechanism for genetic variation in RYR1 is preventing the ion channel from completely closing, allowing Ca2+ to escape, changing the ionic gradient between the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the cytoplasm (141, 143).

Malignant hyperthermia is a life-threatening condition that occurs in response to inhaled anesthetics and/or succhinylcholine, a depolarizing muscle relaxant. This condition is characterized by sustained muscular contraction that causes increased body temperatures, cardiac arrhythmias, and development of metabolic acidosis (111). Identification of individuals who are susceptible to malignant hyperthermia is often determined with an in vitro contracture test (IVCT) or through genetic testing of RYR1 (22, 103, 217).

The association between inhaled anesthetics and RYR1 is classified as CPIC level A and is considered clinically actionable by this consortium (51). In addition, both the European Malignant Hyperthermia Group and the Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States recommend avoiding use of inhaled anesthetics and succhinylcholine in individuals carrying RYR1 variants conferring susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia. Finally, not all individuals who develop malignant hyperthermia carry variants in RYR1, therefore, lack of an RYR1 variant does not guarantee safety for inhaled anesthetic use (22). Therefore phenotypic testing with IVCT may still be warranted even for individuals with RYR1 genetic information.

IFNL3/IL28B.

Interferons (IFN) play a major role in inducing cellular resistance to viral infections (177). Type III IFN, or IFN-λ, have been shown to inhibit the replication of hepatitis C virus (HCV) (114, 132). Hepatitis C is estimated to impact over 100 million individuals worldwide (109). There are seven distinct HCV genotypes; genotype 1 is the most common genotype identified in the global population (82, 182). Although HCV infection is typically a chronic disease, up to 25% of individuals who contract the virus will spontaneously clear the infection (113). The exact reasons for spontaneous clearance of HCV are unknown, but female sex and HCV 1 genotype have been associated with higher incidence of this outcome (83, 206). Individuals who are homozygous for the IFNL3, formerly known as IL28B, major allele for rs12979860 and rs8099917, which are in strong linkage disequilibrium, are also more likely to experience spontaneous remission of hepatitis C infection (44, 81, 83, 104, 161, 163, 199, 224).

Multiple pegylated (PEG)-IFN-α products are commercially available and are indicated for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C (10, 11). The PEG-IFN-α products can be administered as monotherapy or part of a combination therapy regimen with ribavirin and/or other antiviral agents. Individuals with the IFNL3 who carry the major allele for rs12979860 or rs8099917 have an increased likelihood of achieving a complete remission of HCV with PEG-IFN-α combination therapy (75, 123, 163). The CPIC guidelines recommend the IFNL3 genotype can be informative for determining what treatment regimen to prescribe to patients with HCV (142). The clinical relevance of this pharmacogenetic association has been greatly reduced with the approval more efficacious direct-acting antiretrovials (DAA), such as sofosbuvir (1, 152). IFNL3 genotype testing is not recommended for patients receiving DAA-based therapies, as genotype has not been associated with treatment outcomes (1, 17, 39, 189).

INVESTIGATIONAL PHARMACOGENES

Beta-1 Adrenergic Receptor

The beta-1 adrenergic receptor (ADRB1) plays a critical role in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. It is the primary mediator of catecholamine-induced cardiac inotropy and chronotropy, and it is also the primary mediator of catecholamine-induced cardiac toxicity leading to cardiac failure (69). Two common, nonsynonymous polymorphisms in the gene for the ADRB1 were discovered in 1999: rs1801252 (145A>G; Ser49Gly) and rs1801253 (1165G>C; Arg389Gly) (131). These variants are common and in strong linkage disequilibrium in multiple populations (78). In vitro experiments assessing the effects of rs1801252 and rs1801253 on the function of the ADRB1 demonstrate that the minor allele of rs1801252 (145G; Gly49) increases agonist-promoted receptor downregulation (119, 162), and the minor allele of rs1801253 (1165G; Gly389) decreases basal and agonist-promoted receptor activity (122). Therefore, the minor allele at either position would be expected to decrease ADRB1 activity and, hence, decrease cardiac inotropy and chronotropy. Indeed, candidate gene studies have shown an association of these variants with decreased heart rate at rest (25, 27, 160) and in response to exercise (146). These variants were not associated with cardiovascular phenotypes at the genome-wide significance level, but they have been associated with blood pressure and hypertension in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with significance in the range of P = 2.5E-06 to P = 4.1E-04 (http://grasp.nhlbi.nih.gov/Overview.aspx). Meta-analyses have shown that these variants are associated with decreased risk for the development of hypertension and possibly heart failure (94, 102, 105, 126, 212).

In addition to cardiac patho/physiology, the ADRB1 also plays a critical role in cardiac pharmacology. ADRB1 antagonists, most commonly referred to as beta-blockers (e.g., atenolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol, labetalol, metoprolol, propranolol), are among the most commonly prescribed drugs. They are used to treat a variety of cardiovascular conditions, including heart failure, hypertension, postmyocardial infarction, and arrhythmias. Evidence suggests that, in addition to potential physiological and pathophysiological effects, rs1801252 and rs1801253 may also affect beta-blocker responsiveness. The effects are thought to be due to the genetic variant effects on receptor expression and function because neither polymorphism directly interferes with the binding of beta-blockers to the receptor (122, 162). These ADRB1 variants have been associated with attenuated beta-blocker responsiveness in heart rate (52, 98), blood pressure (96, 125, 179, 185), cardiac remodeling (47, 137, 197), and long-term clinical outcomes (108, 122, 137, 194, 197). Notably, consistent replication of any of these associations is not evident in the literature; there are many null, and even some reverse, associations reported (94, 102, 148). However it is important to recognize that only ~1% of studies on these ADRB1 polymorphisms were powered to detect modest-sized effects (102). Therefore, definitive evidence on the effects of these polymorphisms is still needed.

Charcot Marie Tooth-associated Genes

Hereditary neuropathies are clinically and genetically heterogeneous, with more than 200 different forms of hereditary neuropathies described (213). For some of these hereditary neuropathies, the genetic cause has been identified, typically implicating genes relevant to the development or function of peripheral nerves. The most prevalent hereditary neuropathy is Charcot Marie Tooth (CMT) disease, which has an estimated prevalence of around 1:2,500 (181). In general, CMT is characterized by a distal symmetric polyneuropathy with muscle weakness leading to motor handicap. CMT is then subdivided into several subtypes based primarily on clinical features. Type 1 (CMT1) is a demyelinating neuropathy with reduced nerve conduction velocity, while CMT2 is associated with axonal loss and decreased amplitude of nerve action potential. More than 50 genes have been identified that contribute to CMT, with ~30–50 more being theorized based on the proportion of CMT families that are unexplained by comprehensive genetic screening (40). The inheritance pattern of CMT is gene specific, with autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive (CMT4), and x-linked (CMTX) inheritance (167). Genetic screening for CMT is recommended based on clinical phenotype, inheritance patterns, and electrodiagnostic features (70).

Inherited neuropathy accounts for only a small fraction of clinical neuropathy cases. Peripheral neuropathy is a common side effect of diseases such as alcoholism and diabetes, and several classes of cancer chemotherapy, especially microtubule targeting agents (45). Discovery of pharmacogenetic predictors of treatment-induced neuropathy has been identified as an area of immense research interest (202) due to the lack of effective agents for prevention or treatment (86). Similar to CMT, taxane-induced neuropathy is a distal neuropathy with sensory and motor features (169). Early work on taxane-induced neuropathy focused on candidate genes involved in drug metabolism and elimination, including CYP2C8 (89), CYP3A (59), and ABCB1 (85, 134, 180), as previously reviewed (87). Though many associations were detected, replication was a major challenge, and none of these associations are considered validated. Several large clinical trial cohorts have been used to perform GWAS of taxane-induced neuropathy, and the top candidates reported from these GWAS coalesce in CMT-related genes. GWAS of paclitaxel-induced neuropathy have reported associations for FGD4 (rs10771973) (21), a gene verified to cause CMT Type 4H, and SBF2, a gene responsible for CMT Type 4B2 (175). A GWAS of docetaxel-induced neuropathy discovered a variant in VAC14 (rs875858) (88), which has been implicated in pediatric-onset neurological disease (117) and works via binding to the CMT4J-causing FIG4 (116). More recent focus on CMT genes via exome-sequencing has further characterized genetic predisposition to paclitaxel-induced neuropathy (29), including an association with variants in the demyelinating CMT gene ARGHEF10 (34). These findings suggest there may be a subset of patients carrying low-penetrance polymorphisms in CMT-related genes who are sensitive to treatment-induced neuropathy and should be treated with nonneuropathic agents.

Catechol-O-Methyl Transferase

The catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) enzyme is involved in the catabolism of dopamine and other monoamines. In psychiatry and pain the most well-studied variant in the COMT gene is rs4680 (Val158Met). Presence of the rs4680 Met variant results in a more thermolabile enzyme that is less active at average body temperature (46). This translates to higher concentrations of synaptic monoamines, which has implications in disease pathology for both psychiatric and pain disorders (15, 204).

Despite linkage studies supporting an association between loci in the region encompassing COMT and several psychiatric disorders, there is a lack of consistent evidence in case-control studies supporting an association between rs4680 and psychiatric diagnoses (53). However, there appears to be potential for rs4680 to moderate phenotypes of cognition in psychiatry. This is particularly relevant for cognitive aspects that are coupled to the prefrontal cortex, such as working memory in patients with schizophrenia. Investigators who have found a significant association between this SNP and cognition have most often identified the wild-type genotype as associated with worse cognition in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls (31, 79, 130). However, this finding has not been replicated in all studies (186), suggesting that increased dopamine availability is not a universally positive aspect in cognition. Optimal prefrontal cortex functioning may be associated with an inverted U-shaped response curve, with too much or too little dopamine being associated with worse cognitive outcomes and variable activation of dopamine receptor subtypes (174, 216). This is explained well in a recent review of pharmacogenomics studies on medications with dopamine action (stimulants and antipsychotics) that found Met variant carriers were noted to have better improvement in several cognitive measures while taking antipsychotics (174).

With respect to the rs4680 SNP and pain, the variant is more common in those diagnosed with chronic pain conditions such as temporomandibular joint disorders (TMJD) when compared with the general population (61). There is also evidence that this variant should be considered in the context of an identified pain COMT haplotype (Table 4) when measuring pain and medication response (15, 61, 170). Haplotypes associated with pain phenotypes are termed low pain sensitivity (LPS), average pain sensitivity, and high pain sensitivity. Mechanistically, the LPS haplotype produces more COMT enzyme and results in a two- to threefold decreased risk for chronic pain conditions such as TMJD (26, 183).

Table 4.

COMT haplotype-associated pain phenotypes and COMT activity

| rs6269 | rs4633 | rs4818 | rs4680 | Pain Phenotype | COMT Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | C | C | G | LPS | ↑ 4× greater than APS |

| A | T | C | A | APS | |

| A | C | C | G | HPS | ↓11× less than LPS |

Pain phenotypes were compared by Diatchenko et al. (61) using a summary measure of pain sensitivity (based on 16 individual measures), and were determined to have independent effects on pain based on a factorial ANOVA with P ≤ 0.01. COMT, catechol-O-methyl transferase; LPS, low pain sensitivity; APS, average pain sensitivity; HPS, high pain sensitivity.

Pharmacogenomic investigations associating COMT genotype with drug intervention and response in psychiatry and pain have not resulted in conclusive studies with adequate evidence to recommend genotyping before initiating treatment. For example, the wild-type allele has been associated with worse response to antidepressant treatment (23), but this was not supported in a recent meta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor response (147). Adverse antipsychotic events, specifically adverse metabolic events, have been associated carriers of the wild-type allele (67, 68), possibly secondary to higher plasma homocysteine (205), which is known to correlate with cardiovascular disease risk factors (214). However, this association hasn’t persisted in all studies (140) and may be influenced by sex (222). In regard to drugs for pain, wild-type COMT has been associated with increased morphine dose requirements (157). COMT haplotypes have also been related to pain medication dose requirements postoperatively (170) and in the treatment of cancer pain (158). Ultimately, more large-scale pharmacogenomic investigations will be required to determine if the rs4680 SNP moderates the impact of psychopharmacologic agents, and how COMT haplotypes impact pain and treatment response before implementing COMT genotyping for clinical application.

CONCLUSIONS

The genes described in this article provide an overview of how, for many genetic tests, the results can provide information about both disease risk and pharmacologic treatment efficacy or safety. Patient genetic information may be available to clinicians from a variety of sources including disease screening, somatic testing, or direct-to-consumer testing. The genetic information may be obtained by a variety of methods such as single gene tests for specific SNPs, panel testing, or sequencing. Improved understanding of the genetic predictors of disease and treatment outcomes will increase the number of examples of genetics with multiplicative clinical implications. It is therefore important for clinicians to evaluate both the disease and pharmacogenomic implications of genetic tests, to provide comprehensive, personalized care.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.L.P. and D.L.H. conceived and designed research; A.L.P. prepared figures; A.L.P., K.M.W., J.A.L., and D.L.H. drafted manuscript; A.L.P., K.M.W., J.A.L., V.L.E., and D.L.H. edited and revised manuscript; A.L.P., K.M.W., J.A.L., V.L.E., and D.L.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the screening, care, and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis C infection: updated version. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [PubMed]

- 2.Pfizer. Camptosar Label. New York: Pfizer Injectables. http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=533.

- 3.The Clinical and Functional TRanslation of CFTR (CFTR2) https://www.cftr2.org/.

- 4.Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Database http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/cftr/app.

- 5.Associazione Italiana Favismo. Drugs that should be avoided - Official List. G6PD Deficiency Favism Association. http://www.g6pd.org/en/G6PDDeficiency/SafeUnsafe.aspx.

- 6.Elitek Sanofi-Aventis ELITEK Prescribing Information. http://products.sanofi.us/elitek/elitek.html.

- 7.WHO Working Group Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Bull World Health Organ 67: 601–611, 1989. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. AIDSInfo. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-treatment-guidelines/0/.

- 9.Krystexxa Prescribing Information. Lake Forest, IL: Horizon Pharma USA. https://hznp.azureedge.net/public/KRYSTEXXA_Prescribing_Information.pdf.

- 10.Pegasys Prescribing Information. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA. https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/pegasys_prescribing.pdf.

- 11.PegIntron Prescribing Information. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co. https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/p/pegintron/pegintron_pi.pdf.

- 13.Reyataz Prescribing Information. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Meyers Squibb. https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_reyataz.pdf.

- 14.Alvarellos ML, Krauss RM, Wilke RA, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB summary: very important pharmacogene information for RYR1. Pharmacogenet Genomics 26: 138–144, 2016. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen S, Skorpen F. Variation in the COMT gene: implications for pain perception and pain treatment. Pharmacogenomics 10: 669–684, 2009. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ando Y, Saka H, Asai G, Sugiura S, Shimokata K, Kamataki T. UGT1A1 genotypes and glucuronidation of SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan. Ann Oncol 9: 845–847, 1998. doi: 10.1023/A:1008438109725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arias A, Aguilera A, Soriano V, Benítez-Gutiérrez L, Lledó G, Navarro D, Treviño A, Otero E, Peña JM, Cuervas-Mons V, de Mendoza C. Rate and predictors of treatment failure to all-oral HCV regimens outside clinical trials. Antivir Ther 22: 307–312, 2016. doi: 10.3851/IMP3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arias IM. Chronic unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia without overt signs of hemolysis in adolescents and adults. J Clin Invest 41: 2233–2245, 1962. doi: 10.1172/JCI104682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arias JM. Pathogenesis of different types of jaundice. Verh Dtsch Ges Inn Med 82: 2029–2039, 1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avihingsanon A, Tongkobpetch S, Kerr SJ, Punyawudho B, Suphapeetiporn K, Gorowara M, Ruxrungtham K, Shotelersuk V. Pharmacogenetic testing can identify patients taking atazanavir at risk for hyperbilirubinemia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 69: e36–e37, 2015. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldwin RM, Owzar K, Zembutsu H, Chhibber A, Kubo M, Jiang C, Watson D, Eclov RJ, Mefford J, McLeod HL, Friedman PN, Hudis CA, Winer EP, Jorgenson EM, Witte JS, Shulman LN, Nakamura Y, Ratain MJ, Kroetz DL. A genome-wide association study identifies novel loci for paclitaxel-induced sensory peripheral neuropathy in CALGB 40101. Clin Cancer Res 18: 5099–5109, 2012. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bamaga AK, Riazi S, Amburgey K, Ong S, Halliday W, Diamandis P, Guerguerian AM, Dowling JJ, Yoon G. Neuromuscular conditions associated with malignant hyperthermia in paediatric patients: A 25-year retrospective study. Neuromuscul Disord 26: 201–206, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baune BT, Hohoff C, Berger K, Neumann A, Mortensen S, Roehrs T, Deckert J, Arolt V, Domschke K. Association of the COMT val158met variant with antidepressant treatment response in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 33: 924–932, 2008. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayraktar S, Arun B. BRCA mutation genetic testing implications in the United States. Breast 31: 224–232, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beitelshees AL, Zineh I, Yarandi HN, Pauly DF, Johnson JA. Influence of phenotype and pharmacokinetics on beta-blocker drug target pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics J 6: 174–178, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belfer I, Segall SK, Lariviere WR, Smith SB, Dai F, Slade GD, Rashid NU, Mogil JS, Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Liu Q, Bair E, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. Pain modality- and sex-specific effects of COMT genetic functional variants. Pain 154: 1368–1376, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bengtsson K, Melander O, Orho-Melander M, Lindblad U, Ranstam J, Råstam L, Groop L. Polymorphism in the beta(1)-adrenergic receptor gene and hypertension. Circulation 104: 187–190, 2001. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.104.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benson AB III, Venook AP, Bekaii-Saab T, Chan E, Chen YJ, Cooper HS, Engstrom PF, Enzinger PC, Fenton MJ, Fuchs CS, Grem JL, Hunt S, Kamel A, Leong LA, Lin E, Messersmith W, Mulcahy MF, Murphy JD, Nurkin S, Rohren E, Ryan DP, Saltz L, Sharma S, Shibata D, Skibber JM, Sofocleous CT, Stoffel EM, Stotsky-Himelfarb E, Willett CG, Gregory KM, Freedman-Cass DA; National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Colon cancer, version 3.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 12: 1028–1059, 2014. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beutler AS, Kulkarni AA, Kanwar R, Klein CJ, Therneau TM, Qin R, Banck MS, Boora GK, Ruddy KJ, Wu Y, Smalley RL, Cunningham JM, Le-Lindqwister NA, Beyerlein P, Schroth GP, Windebank AJ, Züchner S, Loprinzi CL. Sequencing of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease genes in a toxic polyneuropathy. Ann Neurol 76: 727–737, 2014. doi: 10.1002/ana.24265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beutler E, Yeh M, Fairbanks VF. The normal human female as a mosaic of X-chromosome activity: studies using the gene for C-6-PD-deficiency as a marker. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 48: 9–16, 1962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bilder RM, Volavka J, Czobor P, Malhotra AK, Kennedy JL, Ni X, Goldman RS, Hoptman MJ, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, Kunz M, Chakos M, Cooper TB, Lieberman JA. Neurocognitive correlates of the COMT Val(158)Met polymorphism in chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 52: 701–707, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boisdron-Celle M, Metges JP, Capitain O, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Lecomte T, Lam YH, Faroux R, Masliah C, Poirier AL, Berger V, Morel A, Gamelin E. A multicenter phase II study of personalized FOLFIRI-cetuximab for safe dose intensification. Semin Oncol 44: 24–33, 2017. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bontant T, Le Garrec S, Avran D, Dauger S. Methaemoglobinaemia in a G6PD-deficient child treated with rasburicase. BMJ Case Rep 2014: bcr2014204706, 2014. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boora GK, Kulkarni AA, Kanwar R, Beyerlein P, Qin R, Banck MS, Ruddy KJ, Pleticha J, Lynch CA, Behrens RJ, Züchner S, Loprinzi CL, Beutler AS. Association of the Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease gene ARHGEF10 with paclitaxel induced peripheral neuropathy in NCCTG N08CA (Alliance). J Neurol Sci 357: 35–40, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borg A, Haile RW, Malone KE, Capanu M, Diep A, Törngren T, Teraoka S, Begg CB, Thomas DC, Concannon P, Mellemkjaer L, Bernstein L, Tellhed L, Xue S, Olson ER, Liang X, Dolle J, Børresen-Dale AL, Bernstein JL. Characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deleterious mutations and variants of unknown clinical significance in unilateral and bilateral breast cancer: the WECARE study. Hum Mutat 31: E1200–E1240, 2010. doi: 10.1002/humu.21202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bosma PJ, Chowdhury JR, Bakker C, Gantla S, de Boer A, Oostra BA, Lindhout D, Tytgat GN, Jansen PL, Oude Elferink RP, Roy Chowdhury N. The genetic basis of the reduced expression of bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 in Gilbert’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 333: 1171–1175, 1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bosma PJ, Chowdhury JR, Huang TJ, Lahiri P, Elferink RP, Van Es HH, Lederstein M, Whitington PF, Jansen PL, Chowdhury NR. Mechanisms of inherited deficiencies of multiple UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms in two patients with Crigler-Najjar syndrome, type I. FASEB J 6: 2859–2863, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosma PJ, Seppen J, Goldhoorn B, Bakker C, Oude Elferink RP, Chowdhury JR, Chowdhury NR, Jansen PL. Bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 is the only relevant bilirubin glucuronidating isoform in man. J Biol Chem 269: 17960–17964, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bourlière M, Bronowicki JP, de Ledinghen V, Hézode C, Zoulim F, Mathurin P, Tran A, Larrey DG, Ratziu V, Alric L, Hyland RH, Jiang D, Doehle B, Pang PS, Symonds WT, Subramanian GM, McHutchison JG, Marcellin P, Habersetzer F, Guyader D, Grangé JD, Loustaud-Ratti V, Serfaty L, Metivier S, Leroy V, Abergel A, Pol S. Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin to treat patients with HCV genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis non-responsive to previous protease-inhibitor therapy: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial (SIRIUS). Lancet Infect Dis 15: 397–404, 2015. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braathen GJ. Genetic epidemiology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 126: iv-22, 2012. doi: 10.1111/ane.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ, Helleday T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 434: 913–917, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cai X, Tian C, Wang L, Zhuang R, Zhang X, Guo Y, Lu H, Wang H, Li X, Gao J, Li Q, Wang C. Correlative analysis of plasma SN-38 levels and DPD activity with outcomes of FOLFIRI regimen for metastatic colorectal cancer with UGT1A1 *28 and *6 wild type and its implication for individualized chemotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther 18: 186–193, 2017. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2017.1294286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Canu G, Minucci A, Zuppi C, Capoluongo E. Gilbert and Crigler Najjar syndromes: an update of the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) gene mutation database. Blood Cells Mol Dis 50: 273–280, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carapito R, Poustchi H, Kwemou M, Untrau M, Sharifi AH, Merat S, Haj-Sheykholeslami A, Jabbari H, Esmaili S, Michel S, Toussaint J, Le Gentil M, Ansari-Moghaddam A, Radosavljevic M, Etemadi A, Georgel P, Malekzadeh R, Bahram S. Polymorphisms in EGFR and IL28B are associated with spontaneous clearance in an HCV-infected Iranian population. Genes Immun 16: 514–518, 2015. doi: 10.1038/gene.2015.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlson K, Ocean AJ. Peripheral neuropathy with microtubule-targeting agents: occurrence and management approach. Clin Breast Cancer 11: 73–81, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen J, Lipska BK, Halim N, Ma QD, Matsumoto M, Melhem S, Kolachana BS, Hyde TM, Herman MM, Apud J, Egan MF, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR. Functional analysis of genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): effects on mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity in postmortem human brain. Am J Hum Genet 75: 807–821, 2004. doi: 10.1086/425589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen L, Meyers D, Javorsky G, Burstow D, Lolekha P, Lucas M, Semmler AB, Savarimuthu SM, Fong KM, Yang IA, Atherton J, Galbraith AJ, Parsonage WA, Molenaar P. Arg389Gly-beta1-adrenergic receptors determine improvement in left ventricular systolic function in nonischemic cardiomyopathy patients with heart failure after chronic treatment with carvedilol. Pharmacogenet Genomics 17: 941–949, 2007. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282ef7354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clinicaltrials.gov. Study of Ataluren in Nonsense Mutation Cystic Fibrosis (ACT CF). Identifier: NCT02139306, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02139306?term=NCT02139306&rank=1.

- 49.Clinicaltrials.gov. A Phase 2 Study to Evaluate Effects of VX-661/Ivacaftor on Lung and Extrapulmonary Systems in Subjects With Cystic Fibrosis, Homozygous for the F508del-CFTR Mutation. Identifier: NCT02508207, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02508207.

- 50.Clinicaltrials.gov. A Study to Evaluate the Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of VX-661/Ivacaftor in Pediatric Patients With Cystic Fibrosis. Identifier: NCT02953314, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02953314?term=NCT02953314&rank=1.

- 51.Consortium CPIC. Genes-Drugs. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://cpicpgx.org/genes-drugs/.

- 52.Cotarlan V, Brofferio A, Gerhard GS, Chu X, Shirani J. Impact of β(1)- and β(2)-adrenergic receptor gene single nucleotide polymorphisms on heart rate response to metoprolol prior to coronary computed tomographic angiography. Am J Cardiol 111: 661–666, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Craddock N, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC. The catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) gene as a candidate for psychiatric phenotypes: evidence and lessons. Mol Psychiatry 11: 446–458, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crigler JF Jr, Najjar VA. Congenital familial nonhemolytic jaundice with kernicterus. Pediatrics 10: 169–180, 1952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crigler JF Jr, Najjar VA. Congenital familial nonhemolytic jaundice with kernicterus; a new clinical entity. AMA Am J Dis Child 83: 259–260, 1952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Boeck K, Amaral MD. Progress in therapies for cystic fibrosis. Lancet Respir Med 4: 662–674, 2016. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Boeck K, Munck A, Walker S, Faro A, Hiatt P, Gilmartin G, Higgins M. Efficacy and safety of ivacaftor in patients with cystic fibrosis and a non-G551D gating mutation. J Cyst Fibros 13: 674–680, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Bono J, Ramanathan RK, Mina L, Chugh R, Glaspy J, Rafii S, Kaye S, Sachdev J, Heymach J, Smith DC, Henshaw JW, Herriott A, Patterson M, Curtin NJ, Byers LA, Wainberg ZA. Phase I, dose-escalation, two-part trial of the PARP inhibitor talazoparib in patients with advanced germline BRCA1/2 mutations and selected sporadic cancers. Cancer Discov 7: 620–629, 2017. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Graan AJ, Elens L, Sprowl JA, Sparreboom A, Friberg LE, van der Holt B, de Raaf PJ, de Bruijn P, Engels FK, Eskens FA, Wiemer EA, Verweij J, Mathijssen RH, van Schaik RH. CYP3A4*22 genotype and systemic exposure affect paclitaxel-induced neurotoxicity. Clin Cancer Res 19: 3316–3324, 2013. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dias MM, Pignon JP, Karapetis CS, Boige V, Glimelius B, Kweekel DM, Lara PN, Laurent-Puig P, Martinez-Balibrea E, Páez D, Punt CJ, Redman MW, Toffoli G, Wadelius M, McKinnon RA, Sorich MJ. The effect of the UGT1A1*28 allele on survival after irinotecan-based chemotherapy: a collaborative meta-analysis. Pharmacogenomics J 14: 424–431, 2014. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, Bhalang K, Sigurdsson A, Belfer I, Goldman D, Xu K, Shabalina SA, Shagin D, Max MB, Makarov SS, Maixner W. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Genet 14: 135–143, 2005. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Du K, Sharma M, Lukacs GL. The DeltaF508 cystic fibrosis mutation impairs domain-domain interactions and arrests post-translational folding of CFTR. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 17–25, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nsmb882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Durkacz BW, Omidiji O, Gray DA, Shall S. (ADP-ribose)n participates in DNA excision repair. Nature 283: 593–596, 1980. doi: 10.1038/283593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eccles DM, Mitchell G, Monteiro AN, Schmutzler R, Couch FJ, Spurdle AB, Gómez-García EB; ENIGMA Clinical Working Group . BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing-pitfalls and recommendations for managing variants of uncertain clinical significance. Ann Oncol 26: 2057–2065, 2015. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eckford PD, Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Bear CE. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) potentiator VX-770 (ivacaftor) opens the defective channel gate of mutant CFTR in a phosphorylation-dependent but ATP-independent manner. J Biol Chem 287: 36639–36649, 2012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.393637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eley T, Huang SP, Conradie F, Zorrilla CD, Josipovic D, Botes M, Osiyemi O, Hardy H, Bertz R, McGrath D. Clinical and pharmacogenetic factors affecting neonatal bilirubinemia following atazanavir treatment of mothers during pregnancy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 29: 1287–1292, 2013. doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ellingrod VL, Taylor SF, Brook RD, Evans SJ, Zöllner SK, Grove TB, Gardner KM, Bly MJ, Pop-Busui R, Dalack G. Dietary, lifestyle and pharmacogenetic factors associated with arteriole endothelial-dependent vasodilatation in schizophrenia patients treated with atypical antipsychotics (AAPs). Schizophr Res 130: 20–26, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ellingrod VL, Taylor SF, Dalack G, Grove TB, Bly MJ, Brook RD, Zöllner SK, Pop-Busui R. Risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome in bipolar and schizophrenia subjects treated with antipsychotics: the role of folate pharmacogenetics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 32: 261–265, 2012. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182485888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Engelhardt S, Hein L, Wiesmann F, Lohse MJ. Progressive hypertrophy and heart failure in beta1-adrenergic receptor transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7059–7064, 1999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, Carter GT, Kinsella LJ, Cohen JA, Asbury AK, Szigeti K, Lupski JR, Latov N, Lewis RA, Low PA, Fisher MA, Herrmann D, Howard JF, Lauria G, Miller RG, Polydefkis M, Sumner AJ; American Academy of Neurology; American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine; American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation . Evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: the role of laboratory and genetic testing (an evidence-based review). Muscle Nerve 39: 116–125, 2009. doi: 10.1002/mus.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferraris L, Viganò O, Peri A, Tarkowski M, Milani G, Bonora S, Adorni F, Gervasoni C, Clementi E, Di Perri G, Galli M, Riva A. Switching to unboosted atazanavir reduces bilirubin and triglycerides without compromising treatment efficacy in UGT1A1*28 polymorphism carriers. J Antimicrob Chemother 67: 2236–2242, 2012. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Flume PA, Liou TG, Borowitz DS, Li H, Yen K, Ordoñez CL, Geller DE; VX 08-770-104 Study Group . Ivacaftor in subjects with cystic fibrosis who are homozygous for the F508del-CFTR mutation. Chest 142: 718–724, 2012. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, Mortimer P, Swaisland H, Lau A, O’Connor MJ, Ashworth A, Carmichael J, Kaye SB, Schellens JH, de Bono JS. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med 361: 123–134, 2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gammal RS, Court MH, Haidar CE, Iwuchukwu OF, Gaur AH, Alvarellos M, Guillemette C, Lennox JL, Whirl-Carrillo M, Brummel SS, Ratain MJ, Klein TE, Schackman BR, Caudle KE, Haas DW; Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium . Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for UGT1A1 and atazanavir prescribing. Clin Pharmacol Ther 99: 363–369, 2016. doi: 10.1002/cpt.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gauthiez E, Habfast-Robertson I, Rueger S, Kutalik Z, Aubert V, Berg T, Cerny A, Gorgievski M, George J, Heim MH, Malinverni R, Moradpour D, Mullhaupt B, Negro F, Semela D, Semmo N, Villard J, Bibert S, Bochud PY, Swiss Hepatitis C Cohort Study . A systematic review and meta-analysis of HCV clearance. Liver Int 2017. doi: 10.1111/liv.13401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gelfond D, Heltshe S, Ma C, Rowe SM, Frederick C, Uluer A, Sicilian L, Konstan M, Tullis E, Roach RN, Griffin K, Joseloff E, Borowitz D. Impact of CFTR Modulation on Intestinal pH, Motility, and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Cystic Fibrosis and the G551D Mutation. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 8: e81, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2017.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.European Malignant Hyperthermia Group. Mutations in RYR1. Basel, Switzerland: Universität Basel, https://emhg.org/genetics/mutations-in-ryr1.

- 78.1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, Marchini JL, McCarthy S, McVean GA, Abecasis GR. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526: 68–74, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goldberg TE, Egan MF, Gscheidle T, Coppola R, Weickert T, Kolachana BS, Goldman D, Weinberger DR. Executive subprocesses in working memory: relationship to catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met genotype and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60: 889–896, 2003. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goldgar DE, Easton DF, Deffenbaugh AM, Monteiro AN, Tavtigian SV, Couch FJ; Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC) Steering Committee . Integrated evaluation of DNA sequence variants of unknown clinical significance: application to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet 75: 535–544, 2004. doi: 10.1086/424388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gonzalez-Aldaco K, Rebello Pinho JR, Roman S, Gleyzer K, Fierro NA, Oyakawa L, Ramos-Lopez O, Ferraz Santana RA, Sitnik R, Panduro A. Association with spontaneous hepatitis C viral clearance and genetic differentiation of IL28B/IFNL4 haplotypes in populations from Mexico. PLoS One 11: e0146258, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, Razavi-Shearer K, Razavi H. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 61, Suppl: S45–S57, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grebely J, Page K, Sacks-Davis R, van der Loeff MS, Rice TM, Bruneau J, Morris MD, Hajarizadeh B, Amin J, Cox AL, Kim AY, McGovern BH, Schinkel J, George J, Shoukry NH, Lauer GM, Maher L, Lloyd AR, Hellard M, Dore GJ, Prins M; InC3 Study Group . The effects of female sex, viral genotype, and IL28B genotype on spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 59: 109–120, 2014. doi: 10.1002/hep.26639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Helleday T. The underlying mechanism for the PARP and BRCA synthetic lethality: clearing up the misunderstandings. Mol Oncol 5: 387–393, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Henningsson A, Marsh S, Loos WJ, Karlsson MO, Garsa A, Mross K, Mielke S, Viganò L, Locatelli A, Verweij J, Sparreboom A, McLeod HL. Association of CYP2C8, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and ABCB1 polymorphisms with the pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res 11: 8097–8104, 2005. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, Lavoie Smith EM, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G, Chauhan C, Gavin P, Lavino A, Lustberg MB, Paice J, Schneider B, Smith ML, Smith T, Terstriep S, Wagner-Johnston N, Bak K, Loprinzi CL; American Society of Clinical Oncology . Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 32: 1941–1967, 2014. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hertz DL. Germline pharmacogenetics of paclitaxel for cancer treatment. Pharmacogenomics 14: 1065–1084, 2013. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hertz DL, Owzar K, Lessans S, Wing C, Jiang C, Kelly WK, Patel J, Halabi S, Furukawa Y, Wheeler HE, Sibley AB, Lassiter C, Weisman L, Watson D, Krens SD, Mulkey F, Renn CL, Small EJ, Febbo PG, Shterev I, Kroetz DL, Friedman PN, Mahoney JF, Carducci MA, Kelley MJ, Nakamura Y, Kubo M, Dorsey SG, Dolan ME, Morris MJ, Ratain MJ, McLeod HL. Pharmacogenetic discovery in CALGB (Alliance) 90401 and mechanistic validation of a VAC14 polymorphism that increases risk of docetaxel-induced neuropathy. Clin Cancer Res 22: 4890–4900, 2016. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hertz DL, Roy S, Motsinger-Reif AA, Drobish A, Clark LS, McLeod HL, Carey LA, Dees EC. CYP2C8*3 increases risk of neuropathy in breast cancer patients treated with paclitaxel. Ann Oncol 24: 1472–1478, 2013. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hilgart JS, Coles B, Iredale R. Cancer genetic risk assessment for individuals at risk of familial breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD003721, 2012. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003721.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hisert KB, Heltshe SL, Pope C, Jorth P, Wu X, Edwards RM, Radey M, Accurso FJ, Wolter DJ, Cooke G, Adam RJ, Carter S, Grogan B, Launspach JL, Donnelly SC, Gallagher C, Bruce JE, Stoltz D, Welsh MJ, Hoffman LR, McKone EF, Singh PK. Restoring CFTR function reduces airway bacteria and inflammation in people with cystic fibrosis and chronic lung infections. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195: 1617–1628, 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201609-1954OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hunter J, Thompson RP, Rake MO, Williams R. Controlled trial of phetharbital, a non-hypnotic barbiturate, in unconugated hyperbilirubinaemia. BMJ 2: 497–499, 1971. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5760.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iyer L, Hall D, Das S, Mortell MA, Ramírez J, Kim S, Di Rienzo A, Ratain MJ. Phenotype-genotype correlation of in vitro SN-38 (active metabolite of irinotecan) and bilirubin glucuronidation in human liver tissue with UGT1A1 promoter polymorphism. Clin Pharmacol Ther 65: 576–582, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jin B, Ge-Shang QZ, Li Y, Shen W, Shi HM, Ni HC. A meta-analysis of β1-adrenergic receptor gene polymorphisms in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Biol Rep 39: 563–567, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0771-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jinno H, Tanaka-Kagawa T, Hanioka N, Saeki M, Ishida S, Nishimura T, Ando M, Saito Y, Ozawa S, Sawada J. Glucuronidation of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN-38), an active metabolite of irinotecan (CPT-11), by human UGT1A1 variants, G71R, P229Q, and Y486D. Drug Metab Dispos 31: 108–113, 2003. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson JA, Zineh I, Puckett BJ, McGorray SP, Yarandi HN, Pauly DF. Beta 1-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms and antihypertensive response to metoprolol. Clin Pharmacol Ther 74: 44–52, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kaplan M, Renbaum P, Vreman HJ, Wong RJ, Levy-Lahad E, Hammerman C, Stevenson DK. (TA)n UGT 1A1 promoter polymorphism: a crucial factor in the pathophysiology of jaundice in G-6-PD deficient neonates. Pediatr Res 61: 727–731, 2007. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e31805365c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karlsson J, Lind L, Hallberg P, Michaëlsson K, Kurland L, Kahan T, Malmqvist K, Ohman KP, Nyström F, Melhus H. Beta1-adrenergic receptor gene polymorphisms and response to beta1-adrenergic receptor blockade in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Cardiol 27: 347–350, 2004. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960270610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Khan M, Paul S, Farooq S, Oo TH, Ramshesh P, Jain N. Rasburicase-induced methemoglobinemia in a patient with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Curr Drug Saf 12: 13–18, 2017. doi: 10.2174/1574886312666170111151246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim G, Ison G, McKee AE, Zhang H, Tang S, Gwise T, Sridhara R, Lee E, Tzou A, Philip R, Chiu HJ, Ricks TK, Palmby T, Russell AM, Ladouceur G, Pfuma E, Li H, Zhao L, Liu Q, Venugopal R, Ibrahim A, Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: olaparib monotherapy in patients with deleterious germline BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer treated with three or more lines of chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 21: 4257–4261, 2015. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kim KP, Kim HS, Sym SJ, Bae KS, Hong YS, Chang HM, Lee JL, Kang YK, Lee JS, Shin JG, Kim TW. A UGT1A1*28 and *6 genotype-directed phase I dose-escalation trial of irinotecan with fixed-dose capecitabine in Korean patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 71: 1609–1617, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kitsios GD, Zintzaras E. Synopsis and data synthesis of genetic association studies in hypertension for the adrenergic receptor family genes: the CUMAGAS-HYPERT database. Am J Hypertens 23: 305–313, 2010. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Klingler W, Heiderich S, Girard T, Gravino E, Heffron JJ, Johannsen S, Jurkat-Rott K, Rüffert H, Schuster F, Snoeck M, Sorrentino V, Tegazzin V, Lehmann-Horn F. Functional and genetic characterization of clinical malignant hyperthermia crises: a multi-centre study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 9: 8, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Knapp S, Warshow U, Ho KM, Hegazy D, Little AM, Fowell A, Alexander G, Thursz M, Cramp M, Khakoo SI. A polymorphism in IL28B distinguishes exposed, uninfected individuals from spontaneous resolvers of HCV infection. Gastroenterology 141: 320–325, 2011. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kong H, Li X, Zhang S, Guo S, Niu W. The β1-adrenoreceptor gene Arg389Gly and Ser49Gly polymorphisms and hypertension: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep 40: 4047–4053, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kristeleit R, Shapiro GI, Burris HA, Oza AM, LoRusso PM, Patel M, Domchek SM, Balmana J, Drew Y, Chen LM, Safra T, Montes A, Giordano H, Maloney L, Goble S, Isaacson J, Xiao J, Borrow J, Rolfe L, Shapira-Frommer R. A phase I–II study of the oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor rucaparib in patients with germline BRCA1/2-mutated ovarian carcinoma or other solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 23: 4095–4106, 2017. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.US Food and Drug Administration. Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling. Silver Spring, MD, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm.

- 108.Lanfear DE, Peterson EL, Zeld N, Wells K, Sabbah HN, Williams K. Beta blocker survival benefit in heart failure is associated with ADRB1 Ser49Gly genotype. J Card Fail 21, Suppl: S501, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.06.169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lanini S, Easterbrook PJ, Zumla A, Ippolito G. Hepatitis C: global epidemiology and strategies for control. Clin Microbiol Infect 22: 833–838, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lankisch TO, Moebius U, Wehmeier M, Behrens G, Manns MP, Schmidt RE, Strassburg CP. Gilbert’s disease and atazanavir: from phenotype to UDP-glucuronosyltransferase haplotype. Hepatology 44: 1324–1332, 2006. doi: 10.1002/hep.21361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lanner JT. Ryanodine receptor physiology and its role in disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 740: 217–234, 2012. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, Hamilton SL. Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a003996, 2010. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 345: 41–52, 2001. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lázaro CA, Chang M, Tang W, Campbell J, Sullivan DG, Gretch DR, Corey L, Coombs RW, Fausto N. Hepatitis C virus replication in transfected and serum-infected cultured human fetal hepatocytes. Am J Pathol 170: 478–489, 2007. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ledermann JA. PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol 27, Suppl 1: i40–i44, 2016. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lenk GM, Ferguson CJ, Chow CY, Jin N, Jones JM, Grant AE, Zolov SN, Winters JJ, Giger RJ, Dowling JJ, Weisman LS, Meisler MH. Pathogenic mechanism of the FIG4 mutation responsible for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease CMT4J. PLoS Genet 7: e1002104, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lenk GM, Szymanska K, Debska-Vielhaber G, Rydzanicz M, Walczak A, Bekiesinska-Figatowska M, Vielhaber S, Hallmann K, Stawinski P, Buehring S, Hsu DA, Kunz WS, Meisler MH, Ploski R. Biallelic mutations of VAC14 in pediatric-onset neurological disease. Am J Hum Genet 99: 188–194, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]