Abstract

Background

The association between alcohol misuse and the need for intensive care unit admission as well as hospital readmission among those discharged from the hospital following a critical illness is unclear. We sought to determine whether alcohol misuse was associated with 1) admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) among a cohort of patients receiving outpatient care and 2) hospital readmission among those discharged from the hospital following critical illness.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted with data from 24 Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare facilities between 2004 and 2007. Scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C) questionnaire were used to identify patients with past-year abstinence, lower-risk alcohol use, moderate alcohol misuse, or severe alcohol misuse. The primary outcome was admission to a VA intensive care unit within the year following administration of the AUDIT-C. In an analysis focused on patients discharged from the ICU, the two main outcomes were hospital readmission within 1 year and within 30 days.

Results

Among 486,115 Veterans receiving outpatient care, the adjusted probability of ICU admission within one year was 2.0% (95% CI, 1.7%–2.3%) for abstinent patients, 1.6% (1.3%–1.8%) for patients with lower-risk alcohol use, 1.8% (1.4%–2.3%) for patients with moderate alcohol misuse, and 2.5% (2.0%–2.9%) for patients with severe alcohol misuse. Among the 9,030 patients discharged from an ICU, the adjusted probability of hospital readmission within one year was 48% (46%–49%) in abstinent patients, 44% (42%–45%) in patients with lower-risk alcohol use, 42% (39%–45%) in patients with moderate alcohol misuse, and 55% (49%–60%) in patients with severe alcohol misuse.

Conclusions

Alcohol misuse may represent a modifiable risk factor for a cycle of ICU admission and subsequent hospital readmission.

Keywords: alcohol-related disorders, intensive care units, patient readmission, alcohol consumption, health care utilization, alcohol abuse

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol misuse refers to a spectrum of drinking, ranging from consumption in excess of recommended limits without consequences to a maladaptive pattern of excessive alcohol consumption termed an alcohol use disorder (AUD).1,2 With 88,000 alcohol attributable deaths per year in the United States, alcohol misuse is the third leading cause of preventable mortality and accounts for $25 billion in annual healthcare expenditures.3–6 As effective population-based approaches to management of alcohol misuse continue to evolve,7–9 understanding the relationship between alcohol misuse and potentially preventable and costly measures of healthcare utilization will aid in assessing the benefits of improved alcohol-related services.

ICU admission and hospital readmission are two costly events for the U.S. healthcare system. Between 2000 and 2005, ICU-related costs rose 60% from $57 billion to $81.7 billion, representing almost 1% of the U.S. gross domestic product.10 With the full institution of the federal Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program for fiscal year 2013, some U.S. hospitals may be financially penalized for excessive rates of hospital readmission.11 Understanding modifiable risk factors for ICU admission and hospital readmission may provide some insight for hospital systems to deliver more cost-effective care. Although alcohol misuse is associated with higher rates of hospitalization,12–14 there is little research regarding the association between alcohol misuse and ICU admission or hospital readmission as measures of healthcare utilization.15

The Veteran’s Health Administration (VHA) supports the country’s largest integrated healthcare system and began screening for alcohol misuse in 2004 using the 3 item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C) screening questionnaire.16 As an integrated healthcare system with high rates of alcohol screening, VHA offers a unique opportunity to examine the association between patterns of alcohol consumption and healthcare utilization. This study had two aims: to evaluate the association between alcohol screening and ICU admission in the following year, and among patients discharged from the hospital following an ICU stay, the association between alcohol screening in the year prior to ICU admission and a subsequent hospital readmission. Based on the association between alcohol misuse and numerous illnesses that are commonly cared for in an ICU,17–23 we hypothesized that outpatients with alcohol misuse would have higher rates of ICU admission. We further hypothesized that alcohol misuse would be associated with hospital readmission at one year and at 30 days following hospital discharge in patients who required an ICU admission. Finally, we sought to describe the reasons for ICU admission and hospital readmission in patients with alcohol misuse.

METHODS

Study design and population

This study was a secondary analysis of a retrospective cohort study designed to validate changes in alcohol screening scores over time within the VA healthcare system. Veterans age 18 and older were potentially eligible for the primary study if they received outpatient care at one of 24 VA facilities (in the Northern and Western U.S.) between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007. This four year period represents the time between implementation of alcohol screening and more widespread implementation of brief alcohol counseling within the VA system and thus may be more reflective of care in other U.S. healthcare systems.16,24 Because the primary study was designed to validate changes in alcohol screening scores, patients were included in the primary study if they had alcohol screening performed on two occasions at least twelve months apart during the study period. Patients were excluded if they received no VA care or died in the year after their second alcohol screen. Data were obtained from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, VA National Patient Care Database, VA Vital Status Master file, and VA-Medicare Database. The study had waivers of informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization and was approved by the VA Puget Sound Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Independent variable – Alcohol Screening Categories

All veterans who receive care within the VA system are expected to be offered annual alcohol screening with the 3 question AUDIT-C. AUDIT-C scores were obtained from electronic medical record data, in which providers document alcohol screening that is prompted during clinic visits with a clinical reminder.16 The AUDIT-C is a validated screen for alcohol misuse that asks about past year drinking. It contains one question assessing drinking frequency, one question assessing the number of drinks per typical drinking occasion, and one question assessing frequency of drinking 6 or more drinks on one occasion.25–27 The three items have scores 0–4 which are summed with total scores ranging from 0 to 12 points. A score of 0 denotes abstinence in the past year. Scores of 1–4 denote lower-risk alcohol use, 5–7 moderate alcohol misuse, and 8–12 severe alcohol misuse. These categories were designated a priori based on prior work.28–32 Only the patient’s first AUDIT-C score from the CDW during the study period was used for this analysis. The AUDIT-C does not distinguish former drinkers from lifetime abstainers; these groups differ markedly in the number and severity of their medical comorbidities.17,33 Therefore, consistent with prior studies, we used lower-risk alcohol use as the reference group for all analyses.28–32

Outcome variables

Consistent with the two aims of this study, there were two primary outcome measures. For the first aim evaluating the association between alcohol screening groups and admission to a VA ICU, the primary outcome was any ICU stay ≥ 1 day in the year (1–365 days) following the first alcohol screen. Admission to an ICU was defined as admission to a VA hospital with a bed section code of 12 (medical ICU) or 63 (surgical ICU). Although there is a bed section code for cardiac ICU (13), none of the hospitals included in this sample had dedicated cardiac ICUs. For the second aim, the primary outcome was readmission to a VA hospital within one year (1–365 days) of ICU discharge.

Hospital readmission was defined as any admission to an inpatient VA medical facility. During the study design, hospitalization within one year was chosen as the primary outcome variable for this aim in order to maximize power. However, because many hospital readmissions within 30 days are thought to be preventable, hospital readmissions within 30 days were considered as a secondary outcome variable for this aim.

In order to gain a greater understanding of the reasons for healthcare utilization, we used ICD-9 CM codes for the principal discharge diagnosis of the initial ICU admission and for hospital readmission. Clinical classification software, available through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Utilization Project (http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp), was used to group discharge diagnoses by organ systems.

Covariates

Variables known to be associated with both alcohol misuse and hospital readmission were included as covariates in the multivariable analyses. These included age (< 50 years, 50–64 years, 65–79 years, and 80 years or older), race/ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic, or other), marital status (single or never married, divorced or separated, married, widowed, unknown or missing), VA coverage eligibility (full VA coverage, service-connected <50%, non service-connected), Charlson/Deyo comorbidity index (0–2, 3 or greater)34, and smoking status (current smoker or current non-smoker). Patients were considered to be a current smoker if they had a tobacco diagnosis (ICD-9 305.1, 989.4, v15.82) or a health factor indicating current smoking.35 Data for all covariates were from the year preceding AUDIT-C screening.

Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s chi-square was used to compare differences in patient characteristics across alcohol screening categories. For Aim 1, to determine whether alcohol screening categories were associated with ICU admission in the following year, we constructed a multivariable logistic regression model with alcohol screening category as the predictor and admission to a VA ICU as the outcome variable. The model adjusted for the above specified covariates and estimated cluster robust standard errors to account for correlated data within VA facilities. Post-estimation predictions were then used to determine average adjusted probabilities and confidence intervals and to determine the absolute difference in adjusted probability between alcohol screening categories. This approach, known as regression risk analysis, provides a more intuitive interpretation of study results than odds ratios, allows comparison of risk across groups while holding covariates constant, and is widely recommended when using nonlinear models.36

For Aim 2, to determine whether alcohol screening categories were associated with hospital readmission in the cohort of patients discharged from the hospital following an ICU stay, we constructed two separate multivariable logistic regression models with alcohol screening category as the predictor. For the primary analysis, hospital readmission within one year of ICU discharge was the outcome variable. For the secondary analysis, hospital readmission within 30 days was the outcome variable. Both of these models were adjusted for the same pre-specified covariates; estimated cluster robust standard errors allowed for correlated data within VA facilities. Adjusted probabilities and absolute differences in adjusted probabilities between alcohol screening categories were calculated as in Aim 1.36

In order to examine the robustness of our findings, two sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, to further examine the lower end of the AUDIT-C cutoff for alcohol misuse, we added a fifth alcohol screening category that contained female patients with an AUDIT-C of 3 or 4 and male patients with an AUDIT-C of 4. For this analysis, female patients with an AUDIT-C score of 1or 2 and male patients with an AUDIT-C score of 1–3 were used as the reference group. In the second sensitivity analysis, we excluded women given the small numbers of women with severe alcohol misuse in this sample. Both sensitivity analyses were conducted using the same outcome variables as Aims 1 and 2.

RESULTS

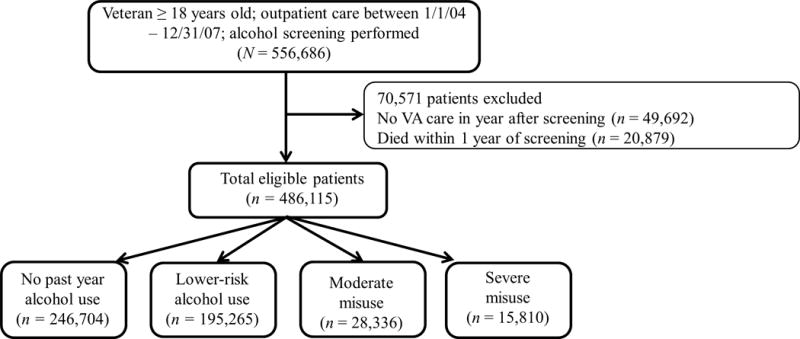

During the study period 556,686 patients were potentially eligible; 486,115 patients were included in this study (Figure 1). The most common reason for exclusion was receiving no VA care during the 1 year follow-up period. Of patients who met inclusion criteria, 20,879 (3.7%) died during the follow-up period. Based on alcohol screening, 51% of patients reported abstinence from alcohol in the year prior to screening, 40% reported lower risk alcohol use; 6% and 3% of patients reported moderate, and severe alcohol misuse, respectively. Patients with moderate and severe alcohol misuse were younger and more likely to be male, current smokers, and have fewer medical comorbidities (Table 1). Compared to patients with lower risk alcohol use, those who reported past year abstinence had more medical comorbidities, were older, and were more likely to have full VA coverage.

Figure 1.

Patients included in the study sample.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients by Results of Alcohol Screening

| No Past Year Alcohol Use (n = 246,704) |

Lower-Risk Alcohol Use (n = 195,265) |

Moderate Alcohol Misuse (n = 28,336) |

Severe Alcohol Misuse (n = 15,810) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* (%) | ||||

| < 50 | 7 | 11 | 14 | 15 |

| 50–64 | 33 | 33 | 42 | 55 |

| 65–79 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 26 |

| 80+ | 25 | 21 | 9 | 4 |

| Gender*(% male) | 94 | 94 | 98 | 98 |

| Race/Ethnicity* (%) | ||||

| White | 67 | 65 | 57 | 52 |

| African American | 8 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Hispanic | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Unknown | 14 | 22 | 29 | 30 |

| Other | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Marital Status* (%) | ||||

| Single | 14 | 13 | 18 | 23 |

| Divorced/Separated | 24 | 24 | 32 | 40 |

| Married | 56 | 56 | 44 | 33 |

| Widowed | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Unknown | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1 |

| VA eligibility*(%) | ||||

| Full VA coverage | 22 | 17 | 15 | 15 |

| Service connected < 50% | 21 | 23 | 20 | 18 |

| Not service connected | 58 | 60 | 65 | 67 |

| Charlson/Deyo Index 3 or Greater* (%) | 12 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

| Current smoker*(%) | 25 | 25 | 40 | 54 |

p < 0.001 for comparison across alcohol screening groups; VA – Veterans Affairs

Among the 486,115 patients included in this study, 9,030 (1.9%) were admitted to an ICU in the year following alcohol screening. Compared to patients with lower risk alcohol use, those with abstinence, moderate, and severe alcohol misuse had a higher unadjusted probability of ICU admission (Table 2). After adjustment for pre-specified covariates, the relationship between alcohol screening category and ICU admission was unchanged with a higher probability of ICU admission in patients with abstinence, as well as moderate and severe alcohol misuse when compared to those with lower-risk alcohol use (Table 2). In a fully-adjusted logistic regression model, compared to patients with lower risk alcohol use, the absolute difference in the adjusted probability of ICU admission was 0.5% (0.3%–0.6%) for abstinent patients, 0.3% (95% CI, 0.03%–0.5%) for patients with moderate alcohol misuse, and 0.9% (95% CI 0.5%–1.2%) for patients with severe alcohol misuse. In patients with severe alcohol misuse, the most common reasons for ICU admission were diseases of the circulatory system (35%), diseases of the digestive system (12%), mental illness (10%), and neoplasm (10%). This pattern of discharge diagnoses was similar to those seen in patients with lower risk alcohol use with the exception of admissions for mental illness which accounted for 1–2% of discharge diagnoses in the other alcohol screening categories (see supplement, eTable 1).

TABLE 2.

Probability of Admission to an Intensive Care Unit in the Year Following Alcohol Screening

| No Past Year Use (n = 246,704) |

Lower-Risk Use (n = 195,265) |

Moderate Misuse (n = 28,336) |

Severe Misuse (n = 15,810) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Unadjusted Probability | 2.14b | 2.08–2.20 | 1.46 | 1.41–1.51 | 1.79b | 1.64–1.94 | 2.55b | 2.30–2.80 |

| Fully Adjusted Probabilitya | 2.03b | 1.72–2.34 | 1.56 | 1.31–1.83 | 1.83c | 1.41–2.26 | 2.45b | 1.97–2.94 |

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, VA coverage eligibility, medical comorbidities, and smoking status.

p < 0.001 when compared to lower-risk alcohol use

p < 0.05 when compared to lower risk alcohol use

In the year following hospital discharge, 4,171 (46%) of the 9,030 patients who were admitted to the ICU were readmitted to a VA hospital. The unadjusted probability of hospital readmission was higher in patients with severe alcohol misuse (56%; 95% CI, 51%–61%) and abstinence (48%; 95% CI, 47%–49%) when compared to those with lower-risk alcohol use (44%; 95% CI 41%–45%) while the probability of hospital readmission in patients with moderate alcohol misuse was similar (42%; 95% CI 38%–46%). After adjustment, the u-shaped association between alcohol consumption and hospital readmission persisted (Table 3). In a fully-adjusted logistic regression model, compared to patients with lower risk alcohol use, the absolute difference in the adjusted probability of hospital readmission within 1 year was 4% (95% CI 2%–6%) for abstinent patients and 11% (95% CI, 6%–17%) for patients with severe alcohol misuse. Patients with moderate alcohol misuse had a 2% (95% CI, 1%–5%) lower adjusted probability of ICU admission. For hospital readmissions, mental illness (26%) replaced diseases of the circulatory system (24%) as the most common discharge diagnosis in patients with severe alcohol misuse (supplement eTable 2).

TABLE 3.

Probability of Hospital Readmission for Patients Admitted to an Intensive Care Unit

| No Past Year Use (n = 5,268) |

Lower-Risk Drinking (n = 2,853) |

Moderate Misuse (n = 506) |

Severe Misuse (n = 403) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Hospital Readmission within 1 year | ||||||||

| Unadjusted Probability | 47.8d | 46.5–49.1 | 42.6 | 40.8–44.4 | 41.9 | 37.6–46.2 | 56.3d | 51.4–61.1 |

| Fully Adjusted Probabilitya | 47.6d | 45.6–49.4 | 43.5 | 41.5–45.4 | 41.5 | 38.6–44.5 | 54.7d | 49.3–60.1 |

|

| ||||||||

| Hospital Readmission within 30 days | ||||||||

| Unadjusted Probability | 18.3b | 17.3–19.3 | 16.0 | 14.7–17.3 | 15.4 | 12.3–18.5 | 23.6d | 19.5–27.8 |

| Fully Adjusted Probabilitya | 18.2b | 15.9–20.4 | 16.3 | 14.2–18.4 | 15.4 | 11.2–19.4 | 23.1c | 18.3–27.8 |

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, VA coverage eligibility, medical comorbidities, and smoking status.

p < 0.05 when compared to lower-risk alcohol use

p < 0.01 when compared to lower-risk alcohol use

p < 0.001 when compared to lower-risk alcohol use

In the pre-specified secondary analysis examining the association between alcohol screening category and hospital readmission within 30 days, 1,594 (18%) of the 9,030 patients were readmitted to a VA hospital. In an unadjusted analysis, there was a similar u-shaped association: 18% (95% CI, 17%–19%) of those with abstinence, 16% (95% CI, 15%–17%) of those with lower-risk alcohol use, 15% (95% CI 12%–19%) of those with moderate alcohol misuse, and 24% (95% CI 19%–28%) of those with severe alcohol misuse were readmitted within 30 days of hospital discharge. In a fully adjusted logistic regression model, this relationship was unchanged; the absolute difference in the adjusted probability of hospital readmission was 7% (95% CI, 3%–11%) for patients with severe alcohol misuse when compared to patients with lower-risk alcohol use (Table 3).

In a sensitivity analysis, women with AUDIT-C scores of 3–4 and men with AUDIT-C scores of 4 were considered as a separate alcohol screening category. In a fully-adjusted logistic regression model, compared to patients with lower risk alcohol use, patients with these scores had a 0.3% (95% CI 0.2%, 0.4%) lower adjusted probability of ICU admission while patients with moderate alcohol misuse no longer had a higher adjusted probability of ICU admission (absolute difference 0.2%; 95% CI −0.03%, 0.44%; p = 0.10). Other findings were essentially unchanged (eTables 3 and 4). In a sensitivity analysis excluding women (data not shown), the findings were also essentially unchanged though the higher adjusted probability of ICU admission among outpatients with moderate alcohol misuse no longer reached statistical significance (absolute difference in adjusted probability 0.2%; 95% CI 0%, 0.4%; p = 0.051).

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the association between alcohol screening categories and ICU admission as well as hospital readmission in patients discharged from the hospital following an ICU stay. As hypothesized, in VA patients screened for alcohol misuse with the AUDIT-C during outpatient care, the adjusted probability of ICU admission was 0.9% higher in patients with severe alcohol misuse when compared to those with lower risk use. In the year following ICU admission, there was an even more marked 11% absolute difference in the adjusted probability of hospital readmission within one year. While these absolute differences appear modest, this conservatively translates to an additional 3,000 intensive care unit admissions each year among veterans receiving care in the VA at an estimated cost of $31,500 per ICU admission.37 These findings are consistent with the observation that alcohol misuse is associated with an increased risk of several of the illnesses that commonly account for ICU admission and hospital readmission.17–22

An unexpected finding was that moderate alcohol misuse was associated with a higher probability of ICU admission but the same risk of hospital readmission compared to lower-risk alcohol use. However, the increased probability of ICU admission among patients with moderate alcohol misuse did not hold in sensitivity analyses varying the lower end of the AUDIT-C cutoff for alcohol misuse and when women were excluded. While the finding in the main analysis may be due to type I error, it is also possible that patients with moderate alcohol misuse may decrease or stop drinking following hospital discharge, thus removing the risk that precipitated their illness.

The association between alcohol misuse and ICU admission is important because alcohol misuse is a potentially modifiable risk factor. There are evidence-based approaches to addressing alcohol misuse in the outpatient setting. Screening and brief intervention involves systematic screening to identify alcohol misuse followed by brief 10–15 minute discussions that provide a framework for healthcare providers to address alcohol misuse with their patients.38–42 Screening and brief intervention received a “B” grade from the United States Preventive Services Task Force.9 However, a major limitation of brief interventions is that even in primary care where they are proven effective, most patients do not respond to a single brief intervention and patients with severe alcohol misuse may be least likely to respond.43 Furthermore, it is unclear whether brief interventions decrease rates of healthcare utilization.8 Referral to treatment is often recommended when patients do not respond to brief intervention, but even in acute care settings most patients with severe alcohol misuse do not accept referral to treatment.44 Therefore, new models of managing severe alcohol misuse, including alcohol use disorders, are needed.7,45,46

Because studies of brief intervention exclude patients who are critically ill, there is currently no evidence-based approach to post-discharge care in ICU survivors with alcohol misuse. Despite longstanding recognition of the high prevalence of alcohol misuse in patients admitted to an ICU,47 no studies have tested interventions to improve outcomes in this high risk population. Therefore, current guidelines for the delivery of multidisciplinary care in the ICU setting are silent on addressing alcohol misuse in ICU survivors.48 Screening and brief intervention is unlikely to be effective in ICU survivors for several reasons. First, most ICU survivors with alcohol misuse have an alcohol use disorder.49,50 As such, a single brief intervention, which is primarily designed to address non-dependent at-risk drinking, is unlikely to be effective.44,51 Second, ICU survivors have high rates of cognitive dysfunction.52 Therefore, asking ICU survivors to weigh pros and cons of their drinking at a time when there may be significant executive dysfunction may not be optimal. Finally, ICU survivors with alcohol misuse have high rates of co-morbid psychiatric illnesses such as depression, anxiety or serious mental illness; the presence of one of these psychiatric comorbidities in addition to alcohol misuse is associated with higher rates of hospital readmission in ICU survivors.53 Current systems of care do little to identify and address these concomitant mental health issues. This was highlighted in the current study where mental illness was the most common reason for hospital readmission among ICU survivors with severe alcohol misuse. Our findings, in conjunction with the previously described unique features of ICU survivors with alcohol misuse suggest the need to develop targeted post-discharge care for this population.54

This study has several potential limitations. First, although the association between alcohol misuse and ICU admission and hospital readmission persists after risk adjustment, there is still the potential for residual confounding. For example, our measure of smoking did not quantify lifetime exposure or separate former from never smokers. Furthermore, there may be residual confounding by socioeconomic status. Second, abstinence was also associated with higher rates of healthcare utilization. This is a consistent finding in studies examining the association between alcohol consumption and health outcomes. Although there may be a “protective effect” of alcohol when consumed in moderation,55 residual or unmeasured confounding from medical comorbidities is a more likely explanation.56,57

Third, this study did not account for ICU admission or hospital readmission outside of the VA system. If patients with lower-risk alcohol use were preferentially admitted to hospitals outside of the VA system, this could lead to differential misclassification and bias the results of this study. While hospitalizations outside of the VA system undoubtedly occurred, there is no reason to suspect that they would have preferentially occurred in patients with lower-risk alcohol use.

It is, however, likely that the rates of ICU admission and hospital readmission reported in this study are underestimated. Although the degree of underreporting cannot be determined, the rates of ICU admission in this study are similar to those in the general population in the U.S.58 However, rates of hospital readmission overall in this study (46%) were lower than those reported in a large study of Medicare beneficiaries (56%).59 Furthermore, the data in this study did not allow planned hospital readmission (for example, a staged cardiac procedure) to be distinguished from unplanned hospital readmission. Death may also be a competing risk for hospital readmission. Patients who died during the study follow-up period were excluded from the parent study and, therefore, not included in this analysis. Because mortality is higher in ICU survivors with alcohol misuse, it is possible that excluding patients who died led to an underestimation of the effect sizes in this study.60

Finally, this study used clinical alcohol screening data as opposed to data obtained from mailed surveys. Since clinical alcohol screening data is obtained face to face, it may be more subject to social desirability bias. Furthermore, problems with the quality of clinical alcohol screening data have been described including the lack of administration of the AUDIT-C in a standardized fashion.61–63 However, we suspect that misclassification resulting from underreporting of AUDIT-C scores would lead to an underestimation of risk for patients with alcohol misuse in the current study.

Conclusion

Alcohol misuse represents a potentially modifiable risk factor for ICU admission and, among ICU survivors, hospital readmission within one year and within 30 days. Novel strategies to reduce healthcare utilization in patients with severe alcohol misuse are needed. To address alcohol misuse in this high risk cohort, studies that develop and test an approach that accounts for unique characteristics of ICU survivors with alcohol misuse, are also needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by Merit Review Award #IIR 08-314 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Program, the Center of Excellence for Substance Abuse Treatment and Education, NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR001082, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K23 AA 021814), the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (K24 HL 089223), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R36 HS 022800). Support for VA/CMS data is provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development, VA Information Resource Center (Project Numbers SDR 02-237 and 98-004). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government or any of the authors institutions. The funding agencies were not involved in the design of this study, analysis of data, or preparation of this manuscript.

Statistical analysis was performed by Dr. Rubinsky. Dr. Bradley obtained funding.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Clark takes responsibility for the content of this manuscript. Drs. Bradley and Rubinsky had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Bradley, Clark, and Moss were responsible for the study concept and design. Drs. Clark, Rubinsky, Moss, Au, Ho, Chavez, and Bradley participated in the acquisition, analysis, and/or interpretation of the data. Drs. Clark and Rubinsky drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

References

- 1.Friedmann PD. Clinical practice. Alcohol use in adults. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):365–373. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1204714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492–501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(5):516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harwood H. Updating Estimates of the Economic Costs of Alcohol Abuse in the United States: Estimates, Update Methods, and Data. In: NIAAAa, editor. Alcoholism. Vol. 98. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2000. p. 4327. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E109. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley KA, Kivlahan DR. Bringing patient-centered care to patients with alcohol use disorders. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1861–1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(9):645–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moyer VA, Preventive Services Task F Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(3):210–218. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000–2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(1):65–71. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b090d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraemer KL, McGinnis KA, Skanderson M, et al. Alcohol problems and health care services use in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and HIV-uninfected veterans. Med Care. 2006;44(8 Suppl 2):S44–51. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223703.91275.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald SA, Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, et al. Association of self-reported alcohol use and hospitalization for an alcohol-related cause in Scotland: a record-linkage study of 23,183 individuals. Addiction. 2009;104(4):593–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rentsch C, Tate JP, Akgun KM, et al. Alcohol-Related Diagnoses and All-Cause Hospitalization Among HIV-Infected and Uninfected Patients: A Longitudinal Analysis of United States Veterans from 1997 to 2011. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1025-y. Published online Feb 26 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chavez LJ, Liu C, Tefft N, et al. Unhealthy Acohol Use in Older Adults: Association with Readmissions and Emergency Department Use 30 days after Hospital Discharge. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.008. Epub Ahead of Print Nov 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley KA, Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Volpp B, Collins BJ, Kivlahan DR. Implementation of evidence-based alcohol screening in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(10):597–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Au DH, Kivlahan DR, Bryson CL, Blough D, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and risk of hospitalizations for GI conditions in men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(3):443–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Wit M, Best AM, Gennings C, Burnham EL, Moss M. Alcohol use disorders increase the risk for mechanical ventilation in medical patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(7):1224–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delgado-Rodriguez M, Mariscal-Ortiz M, Gomez-Ortega A, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of nosocomial infection in general surgery. Br J Surg. 2003;90(10):1287–1293. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moss M, Bucher B, Moore FA, Moore EE, Parsons PE. The role of chronic alcohol abuse in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in adults. JAMA. 1996;275(1):50–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss M, Parsons PE, Steinberg KP, et al. Chronic alcohol abuse is associated with an increased incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome and severity of multiple organ dysfunction in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(3):869–877. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000055389.64497.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien JM, Jr, Lu B, Ali NA, et al. Alcohol dependence is independently associated with sepsis, septic shock, and hospital mortality among adult intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):345–350. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254340.91644.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubinsky AD, Bishop MJ, Maynard C, et al. Postoperative risks associated with alcohol screening depend on documented drinking at the time of surgery. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapham GT, Achtmeyer CE, Williams EC, Hawkins EJ, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Increased documented brief alcohol interventions with a performance measure and electronic decision support. Med Care. 2012;50(2):179–187. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(7):821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley KA, McDonell MB, Bush K, Kivlahan DR, Diehr P, Fihn SD. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(8):1842–1849. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradley KA, Rubinsky AD, Sun H, et al. Alcohol screening and risk of postoperative complications in male VA patients undergoing major non-cardiac surgery. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):162–169. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1475-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubinsky AD, Sun H, Blough DK, et al. AUDIT-C Alcohol Screening Results and Postoperative Inpatient Health Care Use. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(3):296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams EC, Bryson CL, Sun H, et al. Association between Alcohol Screening Results and Hospitalizations for Trauma in Veterans Affairs Outpatients. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(1):73–80. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.600392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris AH, Bryson CL, Sun H, Blough D, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores predict risk of subsequent fractures. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(8):1055–1069. doi: 10.1080/10826080802485972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(11):795–804. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-11-200812020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bridevaux IP, Bradley KA, Bryson CL, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Alcohol screening results in elderly male veterans: association with health status and mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1510–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGinnis KA, Brandt CA, Skanderson M, et al. Validating smoking data from the Veteran’s Affairs Health Factors dataset, an electronic data source. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(12):1233–1239. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleinman LC, Norton EC. What’s the Risk? A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(1):288–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dasta JF, McLaughlin TP, Mody SH, Piech CT. Daily cost of an intensive care unit day: the contribution of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(6):1266–1271. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000164543.14619.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.A cross-national trial of brief interventions with heavy drinkers. WHO Brief Intervention Study Group. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(7):948–955. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beich A, Thorsen T, Rollnick S. Screening in brief intervention trials targeting excessive drinkers in general practice: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):536–542. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):986–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.9.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R. Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers. A randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1039–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaner EF, Dickinson HO, Beyer F, et al. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28(3):301–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saitz R. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care: Absence of evidence for efficacy in people with dependence or very heavy drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(6):631–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, et al. Brief intervention for medical inpatients with unhealthy alcohol use: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(3):167–176. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Maisto SA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of alcohol care management delivered in Department of Veterans Affairs primary care clinics versus specialty addiction treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):162–168. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saitz R, Cheng DM, Winter M, et al. Chronic care management for dependence on alcohol and other drugs: the AHEAD randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(11):1156–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moss M, Burnham EL. Chronic alcohol abuse, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4 Suppl):S207–212. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057845.77458.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haupt MT, Bekes CE, Brilli RJ, et al. Guidelines on critical care services and personnel: Recommendations based on a system of categorization of three levels of care. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(11):2677–2683. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000094227.89800.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark BJ, Smart A, House R, Douglas I, Burnham EL, Moss M. Severity of acute illness is associated with baseline readiness to change in medical intensive care unit patients with unhealthy alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(3):544–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark BJ, Williams A, Cecere Feemster LM, et al. Alcohol Screening Scores and 90-Day Outcomes in Patients With Acute Lung Injury. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(6):1518–25. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318287f1bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saitz R. Candidate performance measures for screening for, assessing, and treating unhealthy substance use in hospitals: advocacy or evidence-based practice? Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(1):40–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-1-201007060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark BJ, Keniston A, Douglas IS, et al. Healthcare Utilization in Medical Intensive Care Unit Survivors with Alcohol Withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(9):1536–1543. doi: 10.1111/acer.12124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clark BJ, Jones J, Cook P, Tian K, Moss M. Facilitators and barriers to initiating change in medical intensive care unit survivors with alcohol use disorders: a qualitative study. Journal of critical care. 2013;28(5):849–856. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Bagnardi V, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: an updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(22):2437–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naimi TS, Brown DW, Brewer RD, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and confounders among nondrinking and moderate-drinking U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(4):369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenfield TK, Kerr WC. Physicians’ prescription for lifetime abstainers aged 40 to 50 to take a drink a day is not yet justified. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(12):2893–2895. doi: 10.1111/acer.12582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Critical Care Statistics. http://www.sccm.org/Communications/Pages/CriticalCareStats.aspx. Accessed March 19, 2015.

- 59.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gacouin A, Tadie JM, Uhel F, et al. At-risk drinking is independently associated with ICU and one-year mortality in critically ill nontrauma patients. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(4):860–867. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bradley KA, Lapham GT, Hawkins EJ, et al. Quality concerns with routine alcohol screening in VA clinical settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):299–306. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hawkins EJ, Kivlahan DR, Williams EC, Wright SM, Craig T, Bradley KA. Examining quality issues in alcohol misuse screening. Subst Abus. 2007;28(3):53–65. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Thomas RM, et al. Factors Underlying Quality Problems with Alcohol Screening Prompted by a Clinical Reminder in Primary Care: A Multi-site Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1125–1132. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3248-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.