Abstract

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of a patient navigator intervention to decrease non-adherence to obtain audiological testing following failed screening, compared to those receiving the standard of care.

Methods

Using a randomized controlled design, guardian-infant dyads, in which the infants had abnormal newborn hearing screening, were recruited within the first week after birth. All participants were referred for definitive audiological diagnostic testing. Dyads were randomized into a patient navigator study arm or standard of care arm. The primary outcome was the percentage of patients with follow-up non-adherence to obtain diagnostic testing. Secondary outcomes were parental knowledge of infant hearing testing recommendations and barriers in obtaining follow-up testing.

Results

Sixty-one dyads were enrolled in the study (patient navigator arm=27, standard of care arm=34). The percentage of participants non-adherent to diagnostic follow-up during the first 6 months after birth was significantly lower in the patient navigator arm compared with the standard of care arm (7.4% versus 38.2%) (p=0.005). The timing of initial follow-up was significantly lower in the navigator arm compared with the standard of care arm (67.9 days after birth versus 105.9 days, p=0.010). Patient navigation increased baseline knowledge regarding infant hearing loss diagnosis recommendations compared with the standard of care (p=0.004).

Conclusions

Patient navigation decreases non-adherence rates following abnormal infant hearing screening and improves knowledge of follow-up recommendations. This intervention has the potential to improve the timeliness of delivery of infant hearing healthcare and future research is needed to assess the cost and feasibility of larger scale implementation.

Keywords: Patient navigation, Early hearing detection and intervention, EHDI, Congenital hearing loss, Randomized controlled clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

As the most common neonatal sensory disorder in the United States, infant hearing loss has an incidence of 1 per 1000 births.1 The sense of hearing is vital, especially during the early years of life and early childhood hearing loss can result in lifelong learning delay and disability. The consequences of delayed diagnosis and failure to obtain timely intervention for infants with hearing loss include significant delays in language, cognitive, and social development2 with profound effects on education and employment.3 The economic costs of hearing loss are substantial and, according to the Centers for Disease Control, the overall lifetime medical, educational, and occupational costs due to deafness for children born in 2000 is estimated to be $2.1 billion.4 The United States Preventive Services Task Force has recognized that early detection of hearing loss has the potential of decreasing language development problems, social and emotional challenges, and learning and behavioral disorders.5 Intervention for hearing loss prior to 6 months of age has profound effects on language expressive measures and social adjustment.6,7 To promote early diagnosis and treatment, universal standards have been developed and dictate that all infants be screened no later than one month after birth, diagnosis of hearing loss should occur before three months of age, and hearing loss treatment should occur before six months of age (1-3-6 rule).8,9 The 2013 Joint Committee on Infant Hearing has placed a great priority on the development of interventions that promote adherence to the 1-3-6 rule because significant delays are present.10 Nationally in 2012, nearly 25% of infants were lost to follow-up after abnormal infant hearing screening.11

Early infant hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) programs are coordinated on a state level and, in spite of multiple initiatives to streamline the process, the diagnostic and hearing loss treatment process is complex and many parents find it difficult to navigate.12 Risk factors for non-adherence to the hearing testing recommendations include rural residence, low level of parental education, low socioeconomic status, and public insurance.13–15 Distance from the hearing testing centers has also been correlated with the time to diagnosis in rural children.16,17 Families of children with hearing loss report that they lack confidence and resources needed for healthcare decision-making for their child.18 Parents of children with hearing loss also lack support through the complex process of hearing loss diagnosis and intervention.19 EHDI programs have attempted to address non-adherence in follow-up; however, there is a lack of standardized and evidence-based approaches to decrease non-adherence to infant hearing testing and treatment. There is some preliminary evidence that contacting parents after discharge may promote rescreening; however, this is not widely performed.20 Current programs typically require parents to make initial contact to establish services and often are not utilized until a diagnosis of hearing loss is made. In spite of these programs, there is no established method to address this problem. In fact, a recent review of the literature found no literature that addresses the effectiveness of initiatives designed to decrease non-adherence in follow-up after infant screening for diagnosis or hearing loss intervention.21

Non-adherence to obtain diagnostic testing has been addressed through patient navigator intervention programs within other areas of healthcare. Navigators are trained healthcare workers who are involved in assessing and mitigating personal and environmental factors involved in the Social Cognitive Theory22 to promote healthcare adherence and improve access to care. They educate patients on health conditions and healthcare systems while expeditiously facilitating adherence to complex healthcare.23 In the field of oncology, patient navigator programs have improved adherence to recommended diagnostic testing after the detection of a screening abnormality and have increased the timeliness of obtaining that testing.24,25 Navigator programs have been especially effective in assisting patients from traditionally underserved backgrounds.26 Improving adherence with medical diagnostic testing27–29 and timely diagnosis and treatment27,30 results in healthcare cost savings.26 The objective of this research was to decrease non-adherence (lost to follow-up rates) to recommended infant audiological testing after failed newborn hearing screening. The aim of this research was to assess the role of a patient navigator intervention to decrease non-adherence with obtaining diagnostic testing of infant hearing and we hypothesized that the utilization of a patient navigator would decrease non-adherence to obtain audiological testing following failed screening, compared to those receiving the standard of care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Institutional review board approval of the protocol was obtained prior to initiating the study (protocol 12-1059-P1H). The protocol was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov prior to initiating the study (NCT01917747).

Participants

We carried out a prospective randomized trial involving a parent or guardian and their infant who failed infant hearing screening and were referred for outpatient audiological evaluation. Within this population, the majority of primary caregivers are mothers and were, thus, the primary candidates for recruitment into this study. The parent and their child (the dyad) who were referred for testing were eligible for participation in this study if they met enrollment criteria including being a: 1) Parent with an infant less than 2 weeks old and born after 34 weeks gestation, 2) Parent whose infant failed hearing screening (either automated auditory brainstem response test or otoacoustic emission test) in one or both ears in the newborn nursery, 3) Parents with a working phone willing to be contacted over the phone by a patient navigator during the first year after birth. Exclusion criteria include: 1) Parents whose infant was hospitalized more than 2 weeks after birth, 2) Parents whose infant was born prior to 34 weeks gestation, 3) Parents of an infant in neonatal intensive care unit, 4) Infants with outpatient audiological follow-up less than 2 weeks from the time of enrollment, or 5) Infants who are wards of the state and cases of adoption.

Sample Size Calculation and Recruitment

The national non-adherence rate following failed infant hearing screening is 25%1 and we proposed that the navigator intervention would decrease the non-adherence rate to 12%. A power analysis was performed and in order to have 80% power to detect this difference (at the 0.05 significance level) a sample size of 60 patients was selected. The power analysis was conducted to guide recruitment in order to detect a difference in the primary outcome (non-adherence to follow-up). Exploratory assessment of associations and trends was conducted for the secondary outcomes and other variables. All potential participant dyads were referred for outpatient definitive audiological testing prior to discharge from the birthing hospital. Potential participants were identified and recruited from 3 primary areas: the newborn nursery of a tertiary University-based medical center (children born within the University system and referred to the University audiology practice), the same University-based audiology practice (children born outside of the University but referred to the University audiology practice), and a state-funded audiology clinic (for children born outside and referred outside the University system). The recruitment team contacted these areas on a daily basis and verified eligibility. Potential participants within the University were contacted in person prior to discharge and those outside the University were contacted by phone within 2 weeks after hospital discharge. The study was discussed with participants and informed consent was obtained.

Randomization and Study Protocol

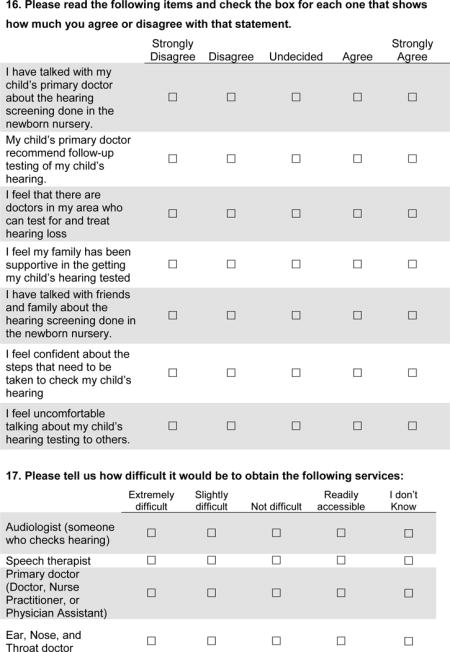

All eligible and enrolled participants were given follow-up appointment dates and time prior to enrollment, typically one month after birth but no later than 3 months after birth. In describing the study to eligible candidates, the parent or guardian was told that their child had referred on a newborn hearing screening for further hearing testing. All participants were told that they would be obtaining an outpatient appointment with the ability to contact the referral clinic at any time with questions or concerns. Participants were told that those agreeing to be involved in the study would be randomized into either a group that will proceed with their appointment as scheduled without further contact from the research staff or they would be placed in a group that would be contacted by a patient navigator before their appointment. At the time of enrollment and informed consent, participants completed a previously tested 26-item entrance questionnaire31 (APPENDIX 1) assessing knowledge of infant hearing testing recommendations and barriers in obtaining follow-up testing. Similar questions regarding knowledge and barriers were asked at the end of the study for all participants in a 24-item exit questionnaire31 (APPENDIX 2). These questionnaires have been used previously to assess parental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding the EHDI system and audiological assessment. Following enrollment, the participant dyad was assigned a study number and was randomized (using block randomization with varying block sizes to assign participants into either the navigator or standard of care arms). Blocked randomization of individuals with variable block sizes (differing numbers of participants per block) ensured equal probabilities of group assignment. A biostatistician created the computer-generated randomization scheme.

Patient Navigation Intervention

Patient navigation was selected as the intervention for this study because it is widely effective in other complex healthcare fields, it is extremely useful and appropriate among rural and low socioeconomic populations, and there is a lack of evidence to support other methods of improving EHDI non-adherence. The Chronic Care Model30 has guided the development and implementation of many patient navigator interventions and this program incorporates key components of this model. Based on this model, navigators have the potential to assist patient in the identification and recruitment of community resources along with health system resources to facilitate delivery of care. The patient navigator program (PNP) focused on elimination of breakdowns in communication, parent decisional support, and coordination of care through the complex EHDI system. An interview guide using semi-structured and open-ended questions was developed for this study and was piloted tested with parents of children who have gone through the EHDI diagnostic process. Participants randomized to the PNP group were assigned to a navigator who contacted the participant by phone within 5 days following the assignment with expected interview duration between 10–30 minutes. Through the initial interview, the navigator used the interview guide to assess the participants’ fears and concerns regarding infant hearing testing, barriers to appointment adherence, and potential connections to community and healthcare system support services. Additionally, during the initial interview, the navigator discussed the 1-3-6 EDHI hearing testing and treatment guidelines. Participants were contacted by phone weekly (text and email were also offered as alternative communication methods) after the initial interview to address key discussion points: 1) the status of the newborn/family and whether newborn hearing testing had occurred, 2) family fears and reservations regarding the infant’s hearing, and 3) the parent’s knowledge of the recommended testing/treatment and the timing of appointments as well as perceived/real barriers to obtaining testing/treatment. During the follow-up interviews, the navigator provided education on the standard recommendations of infant hearing diagnostic testing/treatment and the importance of timely adherence to recommended testing/treatment. The timing of the appointment and the directions to the testing center were discussed. The weekly phone sessions occurred during the first six months after the birth of the child concluding when the diagnostic testing was performed. Participants were given the opportunity to contact the navigator outside of scheduled interviews based on their needs, concerns, and questions.

Navigators identified specific barriers to care and then assisted participants by taking actions tailored to the specific needs of the individual. Social support was provided by supportive listening, providing educational materials, and assisting with referrals for psychological assistance, if needed. Navigators provided instrumental assistance by helping participants with making appointments, resolving child-care problems, and helping with transportation issues. At the participant level, navigators educated participants on the 1-3-6 EDHI recommendations for hearing evaluation and treatment and counseled them on the importance of adherence to follow-up appointments.

Navigators were selected and trained in accordance with a widely accepted model established by the National Cancer Institute Patient Navigator Research Program and the American Cancer Society Patient Navigation Program.32 Patient navigators for this study included a parent of a child with hearing loss and an adult layperson with hearing loss. A bilingual (Spanish-English) navigator was also utilized in this study. The navigators were paid hourly by the primary university conducting the study and they completed onsite training using multiple modalities that included traditional lectures, interactive formats, and role-play with case scenarios. They were trained in the complexity of the EHDI hearing healthcare system and in helping patients navigate through the process in a timely manner. The navigator’s training involved: 1) rural context training, 2) EHDI system and audiological testing training with university audiologists and state EHDI coordinators, 3) medical training with an otolaryngologist, 4) medical center patient services training with clinical support staff to equip the navigator with education regarding logistical problems with obtaining appointments, and 5) navigator telephone training. Following the American Cancer Society patient navigator model, the navigators contacted participants by telephone.32 Adherence to outpatient testing was monitored on a weekly basis. Additional appointment variables were also recorded (number of scheduled appointments, number of attended appointments, number of rescheduled or “no-show” visits). At the conclusion of the study, participants completed the Patient Satisfaction with Navigation questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction with the intervention.33

Control Group (Standard of Care)

According to EHDI standards, all parents of children who fail infant hearing screening are given printed educational materials and may view an educational video regarding infant hearing loss and EHDI services while in the hospital. All participants of the standard of care group were given their outpatient follow-up appointment prior to discharge. Once the participant was discharged from the hospital and/or enrolled in the study he or she did not have any further contact with the research staff. The parent participant had access to discuss any questions or concerns with the office or audiology staff, as is the standard of care practice, but this was parent-initiated contact. There was an automated appointment reminder phone call (which is a medical center standard of care) that occurred 48 hours prior to the appointment, which requested confirmation of the planned adherence to the clinical appointment. The research staff monitored adherence to follow-up of study participants.

Measures

The primary outcome was a dichotomous variable based on whether the child received the outpatient audiological testing during the first six months after birth. Adherence was recorded when the participant presented for the audiological testing in the audiology clinic. Adherence and timing of follow-up was confirmed by cross-referencing with the EHDI state data registry. We also recorded process variables of the navigator intervention including number of telephone sessions, number of missed or terminated navigator sessions, reasons for missed sessions, length of the sessions, and Patient Satisfaction with Navigation questionnaire scores.33 The secondary outcome of interest assessed was the time interval from birth to the attended initial outpatient ABR appointment during the first 6 months after birth. The time interval from birth to final diagnosis was also recorded. Number of no-show office visits and rescheduled visits were also recorded. Failure to obtain a follow-up within 6 months after birth was considered as follow-up non-adherence (lost to follow-up) and 180 days was designated for these participants in time analyses.

Analysis

Data were managed using the REDCap data collection system and was exported into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), and statistical analysis was performed with STATA (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Continuous variables were summarized with descriptive statistics (n, mean, standard deviation) and categorical variables were described with counts and percentages. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The effect of sociodemographic variables on the primary outcome was assessed with Chi Square analysis and univariate/multivariate logistic regression analysis. Differences of follow-up adherence between patient navigator and the standard of care arms were assessed with chi square analysis and odds ratios were calculated. Process variables were analyzed in a similar way. Regression analyses (Cox proportional hazard) were used to detect differences among navigator group and the standard of care group for the time of diagnostic testing. We used a log-rank test to examine differences in the distributions of time to first ABR for each group. Corresponding Kaplan-Meier curves were used to visualize these distributional differences. Comparison of entrance and exit paired data for the study arms was performed with McNemar’s test as well as the Generalized Estimating Equation procedure. The data regarding participant knowledge of hearing loss involved descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies, and ranges) and correlational quantitative methods to compare differences between study arms.

RESULTS

A total of 260 dyads were assessed for eligibility between 2014–2016. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram34 demonstrates the subject recruitment enrollment, allocation, follow-up, and analysis (FIGURE 1). Of those assessed for eligibility, 197 were unable to enrolled and consented for study participation (41 not meeting inclusion criteria, 68 declined to participate, and 88 could not be reached by telephone). A total of 63 dyads were enrolled and two participant dyads withdrew from the study. A total of 61 dyads were included in the final analysis (patient navigator arm = 27 and standard of care arm = 34). The majority of infants were born in the University medical center and referred to the University audiology practice (n=34) with smaller numbers born outside the University system and referred to the University audiology practice (n=15) or born outside the University system and referred to a state-funded audiology practice (n=12). The demographic information of parental participants is presented in TABLE 1. There was a difference in the educational and insurance status between the two study arms; however, subgroup analysis within these areas revealed no significant difference. There was no significant differences in race, age, socioeconomic status, or other demographic factors between the patient navigator arm and the standard of care arm. Approximately 28% of the participants reside in rural counties and the travel distance to the hearing diagnostic center was significantly greater for those participants than those living in urban/suburban counties (61.8 minutes versus 20.4 minutes, p> 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT (CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagram for this study

TABLE 1.

Patient Navigator RCT Study Participant Demographical Data

| Response | Navigation Arm | Standard Arm | Total | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size (%) | 27 (44) | 34 (56) | 61 (100) | ||

| Rural Residence (%) | 0.78 | ||||

| Yes | 8 (13) | 9 (15) | 17 (28) | ||

| No | 19 (31) | 25 (41) | 44 (72) | ||

| Distance to Diagnostic Care (%) | 0.35 | ||||

| Near (0–29 min) | 15 (25) | 18 (30) | 33 (54) | ||

| Moderate (30–59 min) | 10 (16) | 10 (16) | 20 (33) | ||

| Far (60+ min) | 1(2) | 5 (8) | 6 (10) | ||

| Not reported | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | ||

| Method of Transport (%) | 0.70 | ||||

| Personal Vehicle | 19 (31) | 18 (30) | 37 (60) | ||

| Friend/Family | 3 (5) | 5 (8) | 8 (13) | ||

| Public Transport | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | ||

| Not reported | 4 (7) | 11 (18) | 15 (25) | ||

| Race (%) | 1.00 | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 15 (25) | 19 (31) | 34 (56) | ||

| Black/African American | 4 (7) | 6 (10) | 10 (16) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 (8) | 5 (8) | 10 (16) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Native American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 5 (8) | ||

| Language (%) | 0.39 | ||||

| English | 23 (38) | 32 (52) | 55 (90) | ||

| Spanish | 4 (7) | 2 (3) | 6 (10) | ||

| Age (%) | 0.40 | ||||

| 18–25 | 9 (15) | 14 (23) | 23 (38) | ||

| 26–29 | 5 (8) | 5 (8) | 10 (16) | ||

| 30–34 | 11 (18) | 9 (15) | 20 (33) | ||

| 35–39 | 0 | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | ||

| 40+ | 0 | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | ||

| Education (%) | 0.04 | ||||

| Less than Middle School | 2 (3) | 0 | 2 (3) | ||

| Some High School | 1 (2) | 8 (13) | 9 (15) | ||

| High School/GED degree | 7 (11) | 4 (7) | 11 (18) | ||

| Some College | 6 (10) | 9 (15) | 15 (25) | ||

| Completed College | 7 (11) | 12 (20) | 19 (31) | ||

| Graduate Degree | 2 (3) | 0 | 2 (3) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | ||

| Income (%) | 0.16 | ||||

| <%10,000 | 4 (7) | 10 (16) | 14 (23) | ||

| $10,000–$20,000 | 8 (13) | 5 (8) | 13 (21) | ||

| $20,000–$30,000 | 2 (3) | 7 (11) | 9 (15) | ||

| $30,000–$60,000 | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | 7 (11) | ||

| >$60,000 | 6 (10) | 8 (13) | 14 (23) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 4 (7) | ||

| Marital Status (%) | 0.27 | ||||

| Single/Never Married | 7 (11) | 15 (25) | 22 (36) | ||

| Married/Domestic Partner | 18(30) | 18 (30) | 36 (59) | ||

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | ||

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | ||

| Child Insurance (%) | 0.048 | ||||

| Medicaid | 8 (13) | 19 (31) | 27 (44) | ||

| Private or HMO/PPO | 10 (16) | 11 (18) | 21 (34) | ||

| None | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | ||

| Other | 6 (9) | 1 (2) | 7 (11) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | ||

| Family Hearing Loss History (%) | 0.86 | ||||

| Yes | 6 (9) | 5 (8) | 11 (18) | ||

| No | 14 (23) | 17 (28) | 31 (50) | ||

| Unsure | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | ||

| Not reported | 7 (11) | 11 (18) | 18 (30) | ||

| Tobacco Use During Pregnancy (%) | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 5 (8) | ||

| No | 23 (38) | 28 (46) | 51 (84) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 5 (8) | ||

| Alcohol Use During Pregnancy (%) | 0.45 | ||||

| Yes | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | ||

| No | 24 (39) | 31 (51) | 55 (90) | ||

| Not reported | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 5 (8) | ||

| Drug Use During Pregnancy (%) | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | |

| No | 25 (41) | 31 (51) | 56 (92) | ||

| Not Reported | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 5 (8) | ||

During the first 6 months following birth, adherence to audiological follow-up was monitored in all 61 participants and cross-referenced with the EHDI state data registry. A significantly lower percentage of participants in the patient navigation arm were non-adherent to follow up compared to the standard of care arm (7.4% versus 38.2%, p=0.005) (FIGURE 2); thereby, confirming the hypothesis of this study. According to the state registry, those that were non-adherent to follow up in this study did not receive any audiological diagnostic care at any facility within the state. Of those from rural counties (n=17), none of navigated participants were non-adherent to follow up while 44% of those in the standard of care arm were non-adherent to follow up (p=0.03) (FIGURE 2). The timing of the diagnostic appointment was 67.9 days (range 10 – 180 days) after birth for the navigated participants versus 105.9 days (range 29 – 234 days) after birth for the standard of care participants. The distribution of this time interval differed significantly between study arms (p=0.01) (FIGURE 3). According to the state EHDI registry, one participant in the navigation arm was non-adherent with the University audiology practice follow-up, but had follow-up at another audiology practice outside of the study sites 10 days after birth. We assessed the effect of variables on non-adherence, which included rural residence, distance to diagnostic center, number of children in family, race, language, caregiver age, caregiver educational level, household income, marital status, child insurance type, family history of hearing loss, tobacco/alcohol/illicit drug use during pregnancy. Univariate analysis revealed that marital status was the only variable affecting non-adherence with 41% of unmarried caregivers non-adherent to follow-up compared with 14% of married caregivers (p=0.02). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was then conducted based on this finding and when controlling for maternal marital status, participants receiving the patient navigation intervention had 83% lower odds of non-adherence than standard of care participants (p=0.04).

FIGURE 2.

Non-adherence (Lost to follow-up rates) to audiological diagnostic testing

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of time (days after birth) to outpatient audiological diagnostic testing following failed newborn hearing screening (p=0.010)

During the diagnostic evaluation multiple appointments may be required for a variety of reasons (i.e. – rescheduling, failure to follow-up, failure of child to sleep through ABR testing, middle ear fluid present) and appointment variables were assessed (TABLE 2). Navigated participants had a higher average number of attended appointments compared with the standard of care participants (p=0.01). Diagnostic testing was completed within 3 months in 52% of the entire sample (56% in the navigation arm and 48% in the standard of care arm, p=0.57). The timing of a final diagnosis was 96.8 days (range 10–236 days) after birth for the navigated participants versus 114.7 days (range 29–234 days) after birth for the standard of care participants. Four children in the study were diagnosed with congenital hearing loss (2 from the navigation arm and 2 from the standard of care arm). These children sought care outside the primary institution following diagnosis and no further outcome data is available.

TABLE 2.

Appointment variables of study participants

| Navigation Arm | Standard Arm | Total | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appointments Scheduled | 1.8 (1–5) | 1.72 (1–4) | 1.75 (1–5) | 0.95 |

| Appointments Attended | 1.32 (0–4) | 0.79 (0–2) | 1.02 (0–4) | 0.01 |

| Non-compliant Appointments (Reschedule or No-show) | 0.48 (0–2) | 0.94 (0–4) | 0.74 (0–4) | 0.17 |

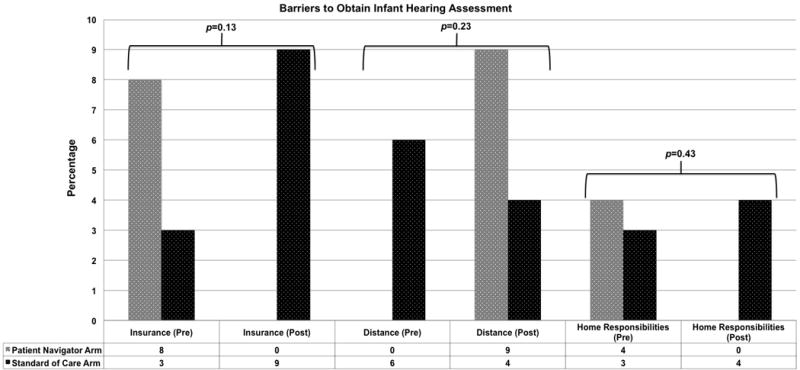

The entrance and exit questionnaire data was available for 43 participants and revealed their experiences with the infant hearing assessment process as well as their knowledge of recommendations and perception of barriers regarding infant hearing healthcare. Approximately 16% of parents did not understand why their child had a hearing-screening test in the hospital; however, at the entrance of the study, 98% of participants agreed that obtaining follow-up for their child’s hearing was important. Regarding outpatient testing, 66% of participants reported that they did not know what to expect and 52% reported that they were not knowledgeable regarding the testing process. In assessing knowledge of infant hearing loss and treatment, 33% did not know the recommended time for infant hearing diagnosis (within 3 months of birth). The participants in the patient navigation arm increased in their knowledge of the recommendations on outpatient audiological follow up during the course of the study (54% correct on entrance versus 78% correct on exit) compared with those in the standard of care arm (76% correct on entrance versus 52% correct on exit) (p=0.004) (FIGURE 4). Overall, the participants reported a high level of confidence with obtaining follow-up (97%) at the beginning of the study, which was also reflected on the exit questionnaire (100%). At the conclusion of the study, 74% reported that they would be comfortable talking about their child’s hearing with others and 98% were willing to provide information regarding the hearing testing process to other parents. Multiple barriers to obtain follow-up testing were assessed in the entrance and exit questionnaires (FIGURE 5).

FIGURE 4.

Assessment of participant knowledge of EHDI recommendations regarding timing of audiological diagnostic testing and treatment of hearing loss (diagnosis by 3 months and treatment by 6 months of age) at the time of study enrollment and exit

FIGURE 5.

Assessment of participant barriers to obtain infant hearing assessment at the time of study enrollment and exit.

Data from the patient navigation intervention were analyzed in 25 of the 27 participants receiving the intervention and results were compared between rural residents and urban residents (TABLE 3). Data regarding navigation variables was incomplete with 2 participants and this was not included in the analysis. The navigator contact with participants occurred primarily over telephone calls, but some communication occurred through mobile phone texting. Contact with patient navigation participants was complicated by inactive mobile phone service (monthly minutes cellular phone plans) or disconnected numbers. Patient navigation satisfaction was assessed at the conclusion of the study and the intervention was rated highly (TABLE 4).

TABLE 3.

Patient navigation intervention variables

| Rural Participants | Urban Participants | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Participants | 7 | 18 | 25 |

| Average Number of Attempted Phone Calls | 9.3 (1–20) | 5.7 (1–15) | 6.7 |

| Average Number of Phone Navigator Sessions | 3 (1–8) | 3 (0–13) | 3 |

| Average Number of Voicemail Messages | 2.6 (0–9) | 1.6 (0–4) | 1.9 |

| Average Number of Phone Call to the Navigator from Participants | 0.14 (0–1) | 0.33 (0–3) | 0.28 |

| Average Number of Text Conversations | 3.6 (0–13) | 1.94 (0–9) | 2.4 |

TABLE 4.

Patient navigation satisfaction data

| Question | Rural Participants | Urban Participants | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| My navigator gives me enough time (%) | |||

| Agree | 6 (86) | 15 (83) | 21 (84) |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not Reported | 1 (14) | 3 (17) | 4 (16) |

| My navigator makes me feel comfortable (%) | |||

| Agree | 6 (86) | 15 (83) | 21 (84) |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not Reported | 1 (14) | 3 (17) | 4 (16) |

| My navigator is dependable (%) | |||

| Agree | 6 (86) | 15 (83) | 21 (84) |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not Reported | 1 (14) | 3 (17) | 4 (16) |

| My navigator is courteous and respectful to me (%) | |||

| Agree | 6 (86) | 15 (83) | 21 (84) |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not Reported | 1 (14) | 3 (17) | 4 (16) |

| My navigator listens to my problems (%) | |||

| Agree | 6 (86) | 14 (78) | 20 (80) |

| Disagree | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (4) |

| Not Reported | 1 (14) | 3 (17) | 4 (16) |

| My navigator is easy to talk to (%) | |||

| Agree | 6 (86) | 14 (78) | 20 (80) |

| Disagree | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (4) |

| Not reported | 1 (14) | 3 (17) | 4 (16) |

| My navigator cares about me personally (%) | |||

| Agree | 6 (86) | 14 (78) | 20 (80) |

| Disagree | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (4) |

| Not Reported | 1 (14) | 3 (17) | 4 (16) |

| My navigator figures out the important issues is my healthcare (%) | |||

| Agree | 6 (86) | 13 (72) | 19 (76) |

| Disagree | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (4) |

| Not Reported | 1 (14) | 4 (22) | 5 (20) |

| My navigator is easy to contact (%) | |||

| Agree | 6 (86) | 14 (78) | 20 (80) |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not Reported | 1 (14) | 4 (22) | 5 (20) |

DISCUSSION

Pediatric hearing loss constitutes a major public health problem and delayed diagnosis can lead to life-long communication deficits. Early identification and treatment of infant hearing loss is essential but unfortunately delayed in many children.16,17,35 This research addresses a significant gap in the field of early hearing diagnosis and intervention research. There is no literature that addresses the efficacy of initiatives designed to decrease non-adherence in follow-up after infant screening for diagnosis or hearing loss intervention. Contact with parents after infant hearing screening may influence follow-up.20 Parent-to-parent programs, such as Guide By Your Side,36 are available in many states and may reduce parental isolation and boost parental acceptance of the child’s condition.19 Current programs typically require the parents to make initial contact to establish services and often are not utilized until a diagnosis of hearing loss is made. No previous studies have examined the use of a patient navigator following infant hearing screening; however, navigation is an intervention model that is well suited to address non-adherence. The original concept and development of this intervention stems from the findings of the American Cancer Society National Hearings on Cancer in the Poor in 1989 and the subsequent work of Dr. Harold Freeman to develop the first patient navigation program to promote timely cancer treatment in the inner city of New York.37 Since that pilot program, many cancer centers have been using patient navigators to improve the quality and timeliness of care. The primary importance of this program, according to this study, is demonstrated in the decreased number of children that are lost to follow-up for diagnostic testing within the first 6 months after birth (7.4% in navigated dyads versus 38.2%). Of the patient that do present for follow-up, the navigation group demonstrated a decreased time to first appointment compared with the standard of care group (67.9 days after birth verus 105.9 days after birth, respectively). Randomization in study arm allocation helps to strengthen the validity of the findings. The standard of care group was close to the recommended 3-month diagnostic target and the clinical significance of the time differences between the study groups is unknown. Further longitudinal research is needed to determine if the earlier diagnostic testing in navigated participants translates to earlier treatment and/or improved speech and language outcomes. Based on the findings of this study, it will be important to study the effect of ongoing patient navigation may expedite treatment of hearing loss in those that are identified through the EHDI program and if patient navigation may improve compliance with device use (either hearing aid or cochlear). In addition, even with a small sample of rural participants, the intervention was particularly efficacious in rural residents. Studying this intervention in such vulnerable populations, may inform clinicians of the most appropriate environment to implement patient navigation. A larger multi-institutional effectiveness study will be needed to assess the benefit of navigation in diverse populations and maximize the understanding of implementation factors that are critical to potential scale-up of this intervention. Such research could inform state-level policy and services impacting children with hearing loss and set the stage for a national multi-site implementation trial and potential scale-up to maximize public health impact.

Many efforts are underway in EHDI programs nationwide to improve infant hearing testing. Screening tests such as automated ABR and OAE have many false-positive results that lead to medical staff and parents dismiss and devalue the screening results and the importance of definitive adherence of infant.31 Double screening while in the newborn nursery is currently being investigated to decrease the false positive rate. Further efforts to improve adherence include hospital scheduling of outpatient testing and more effective communication with primary care physicians. Better communication between EHDI programs and primary care physicians may also improve adherence rate. This will provide additional opportunities to educate providers on the importance of timely infant hearing assessment. Many factors and barriers complicate timely access to healthcare. Misinformation, inconsistent care, cultural or health beliefs, socioeconomic status, mistrust of the healthcare system, and lack of social support influence non-adherence within healthcare.25 Within the EHDI field, factors complicating access to care include poor communication of hearing screening results, difficulty in obtaining outpatient testing, inconsistencies in healthcare information from primary care providers, lack of local resources, insurance-related healthcare delays, and conflict with family and work responsibilities.38 Addressing these barriers to care is complicated and may require multiple approaches. Families of children with hearing loss report that they lack confidence and resources needed for healthcare decision-making for their child.19 Parents of children with hearing loss also lack role models who have been through the complex process of hearing loss diagnosis and intervention.19 In previous research, prenatal educational modules39 and social worker counseling40 have not demonstrated significant benefit in promoting rescreening after a failed infant hearing screening. The personalized patient support and continuity of education and assistance may differentiate patient navigation from other care coordination models. This method of educating patients through patient navigation may be a potential mechanism for improved adherence with testing in this population, as there was evidence in this study of an improved knowledge base in navigated participants regarding EHDI hearing assessment and treatment recommendations. Navigation also has the potential to address multiple personal and external barriers that prevent adherence and access to care. A small percentage of the participants in this study reported on barriers to obtain infant hearing assessment; however, there was a trend toward a decrease in insurance barriers and home responsibilities barriers in the navigated patients at the conclusion of the study. A sampling bias is present in barrier assessment in this study as there is a lack of data from those that were lost to follow up and the responses of those participants would likely be informative. Further research is needed to capture data regarding barriers on those lost to follow up which may employ participant interviews to identify barriers to care. In spite of modest recruitment, the study was able to detect a statistically significant relationship with non-adherence and unmarried status. Future research will need to involve a larger multi-site effectiveness study that would assess the role of these important variables.

Patient navigation has been successfully implemented within the oncology field to improve access to care in underserved populations and overcoming barriers to their care. A variety of types of navigators has been reported and may include lay people who have had personal experience with the disease and represent the population they were serving.41 Others have reported using professional health care workers42 or social workers43 to perform navigation activities. Bilingual navigators may further improve adherence with non-English speakers.44 The structure of a navigation intervention may involve a highly structured guide or assessment tool or an informal discussion of barriers to care.42,43,45,46 Within the field of oncology, navigators have assisted patients in overcoming obstacles such as lack of transportation, lack of insurance, poor coordination of healthcare appointments, language barriers, and limited healthcare literacy.24,43,45 The timing of navigation is also associated with the success of such a program43 as navigation is more effective if it is initiated shortly after an abnormal screening test and may increase adherence with obtaining definitive diagnostic testing. The implementation and sustainability of patient navigation within infant hearing healthcare is dependent on cost. There is a lack of cost assessment of patient navigation within established oncology navigation programs; however, one such program reported an increase in cost of $275 per patient with patient navigation compared with the control group during the course of screening testing leading to diagnostic testing.42 The cost of a patient navigation program within EHDI programs is unknown and deserves further study. Method of intervention delivery also deserves further attention, as it may be possible to deliver patient navigation through remote access or telehealth link. Telemedicine may also allow connection of patients to providers; however, consistent delivery of infant hearing diagnostic testing can be complicated by cost and fidelity of testing. Telemedicine may also be a means to education caregivers and audiologists in remote areas to improve efficiency and accuracy of infant diagnostic hearing testing. Further research is needed on cost assessment and cost effectiveness of telemedicine interventions and other interventions developed to expand access to care.

This study was complicated by difficulty in recruiting all eligible study participants. When evaluating potential participation into the study, 68 parents did not wish to participate, primarily due to concerns with randomization in study arm allocation. Most of these parents expressed concern and did not wish to be randomized into the control group as they wished to receive every possible resource to aid in their child’s hearing testing follow-up. Others expressed concern over being enrolled in a research study, as they perceived they might receive substandard care. In spite of careful explanation of the study, these 68 did not wish to participate. A concerning number of participants (N=88) were potentially eligible for the study; however, they could not be contacted by phone. Most of these potential participants had provided mobile cell numbers; however, when research staff attempted to contact these individuals their phone usage minutes had been maximized or the number was no longer in service. Most participants did not provide alternative numbers; therefore, we were unable to contact them. Some of these patients may have been discharged from the primary University recruitment site during evenings or weekends and were not visited by study staff while in the hospital. Adjustments were made to recruiting methods to prevent the loss of these participants. Most of the 88 parents were referred to a facility outside the main university and there was no direct contact between that clinic, the university, or the research staff. This group of parents is an important subset of patients that need further research and attention. Parents that leave a small birthing hospital and are not given follow-up appointments and cannot be contacted by phone are at a significant risk for non-adherence. Additional uncontrolled variables and design limitations to this study may limit the generalizability of the findings. Since these participants were never contacted, informed consent was not obtained and we are unable to investigate the status of follow-up or outcomes of this group. It may be possible to increase recruitment among participants such as these by sending study information documents to the home address of these participants. By partnering with state EHDI system, it may be also possible to increase recruitment by sending study information to the primary care physician caring for that newborn. Connecting with the parents who were not enrolled initially into the study could provide valuable information regarding knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding infant hearing testing adherence. Increased efforts to contact the parents prior to discharge may also bear fruit.

Attention bias is a potential limitation of this study as the intervention group may have had improved adherence to follow-up due to increased contact alone while the standard of care group had less contact and thus had poorer adherence. While this was not directly controlled for in this efficacy study, other studies that have had increased contact with parents through prenatal educational modules39 and social worker counseling40 has not demonstrated significant benefit in promoting rescreening after a failed infant hearing screening when compared with control groups. The mechanism behind the efficacy of navigation delivery is unknown and further research, through mixed quantitative and qualitative methods, is needed. Another potential limitation includes selection bias with differences in the demographics of the study samples. These differences could influence the results (i.e. overall educational level and insurance status); however, subgroup analyses within these areas reveal no significant differences and household income is similar between the two study arms. An additional factor that could influence the outcomes of this study involves the type of education and level of communication provided in different birthing hospitals (prior to enrollment). Randomization in the study design may decrease the influence of this factor; however, there remains significant variability in the teaching provided directly by healthcare staff (or lack thereof), as well as, the educational resources provided to parents of infants who fail newborn screening. An additional limitation includes a lack of long-term follow up and assessment of the effect of patient navigation on timing of treatment for those diagnosed with hearing loss in this study. Finally, this study was limited in that a single parent or caregiver was targeted for the intervention; however, other caregivers (grandparents or other family members) may be vital targets for navigation and further research is needed to assess the role of other care providers in adherence to outpatient diagnostic testing.

Patient navigation is a promising intervention to promote adherence to infant hearing assessment following failed screening. Further work is needed in this field to assess, through multivariate analysis, key factors that influence non-adherence with testing. By identification of the key factors in non-adherence, navigation may be modified and customized to target those factors to maximize appointment adherence. The method of navigation intervention delivery is an area for future research as well. The lack of consistent phone service in lower socioeconomic groups is a significant barrier to communication in healthcare, which also complicated patient navigation in this study. In-person delivery of navigation could help address this communication gap. Home visits with participants would be a potential method to increase the strength of the patient-navigator relationship. Development and implementation of a community-based navigation program that will monitor long-term hearing outcomes may have greater reach into remote areas to educate and support these patients. Further research is needed to investigate the effectiveness of patient navigation on a larger statewide level and investigate that implementation factors that enable patients to successfully navigation the hearing healthcare system. Additionally, assessment of the cost of patient navigation may influence the likelihood of integrating it into state EHDI programs. Performing cost-benefit analysis of patient navigation in the future will require long-term assessment of speech and language outcomes along with costs associated with rehabilitation and education of children with hearing loss.

CONCLUSION

The objective of this research was to decrease non-adherence (lost to follow-up rates) to recommended infant audiological testing after failed newborn hearing screening. Through a randomized controlled prospective design, this study demonstrated the efficacy of a patient navigator intervention to decrease non-adherence with obtaining diagnostic testing of infant hearing and to expedite diagnostic evaluation when compared with the standard of care. Furthermore, patient navigation improves caregiver knowledge of EHDI infant hearing testing recommendations. This type of intervention is promising to promote adherence to timely diagnostic testing and intervention. Further research is needed to assess the feasibility of larger scale implementation within state EHDI systems and to assess the cost of patient navigation.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This work was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the University of Kentucky Center for Clinical and Translational Science (UL1TR000117) (BN, TS), Triological Society Career Development Award (MLB), National Institute of Mental Health (R34MH106661) (CRS), and National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (1K23DC014074)(MLB). MLB is a member of the Surgical Advisory Board of Med El Corporation.

APPENDIX 1. Newborn Hearing Parent Entrance Questionnaire

APPENDIX 2. Newborn Hearing Parent Exit Questionnaire

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: 1b

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no other financial relationships or conflicts of interest to disclose pertaining to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Hearing Loss in Children. 2014 Annual Data Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Program. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/ehdi-data2014.html. Accessed January 9, 2017.

- 2.Erenberg A, Lemons J, Sia C, Trunkel D, Ziring P. Newborn and infant hearing loss: detection and intervention. American Academy of Pediatrics. Task Force on Newborn and Infant Hearing, 1998–1999. Pediatrics. 1999;103:527–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holden-Pitt L, Diaz J. Thirty years of the annual survey of deaf and hard of hearing children and youth: a glance over the decades. Am Ann Deaf. 1998;143:72–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hearing Loss in Children. Data and Statistics. Accessed September 26, 2016, at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/data.html.

- 5.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Universal screening for hearing loss in newborns: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics. 2008;122:143–148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshinaga-Itano C. Efficacy of early identification and early intervention. Semin Hear. 1995;16:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshinaga-Itano C. Levels of evidence: universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS) and early hearing detection and intervention systems (EHDI) J Commun Disord. 2004;37:451–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. National Institutes of Health, Office of Medical Applications Research, U.S. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Consensus development conference on early identification of hearing impairment in infants and children. Vol. 11. Bethesda, Md.: National Institutes of Health; 1993. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Joint Committee on Infant Hearing 1994 position statement. Pediatrics. 1995;95:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joint Committee on Infant Hearing of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Muse C, Harrison J, Yoshinaga-Itano C, et al. Supplement to the JCIH 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early intervention after confirmation that a child is deaf or hard of hearing. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1324–49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Hearing loss in Children. 2012 Annual Data Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Program. Accessed May 24, 2016, at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/ehdi-data2012.html.

- 12.DesGeorges J. Family perceptions of early hearing, detection, and intervention systems: Listening to and learning from families. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2003;9:89–93. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavalcanti HG, Guerra RO. The role of maternal socioeconomic factors in the commitment to universal newborn hearing screening in the Northeastern region of Brazil. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76(11):1661–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu CL, Farrell J, MacNeil JR, Stone S, Barfield W. Evaluating loss to follow-up in newborn hearing screening in Massachusetts. Pediatrics. 2008;21(2):e335–343. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lester EB, Dawson JD, Gantz BJ, Hansen MR. Barriers to the Early Cochlear Implantation of Deaf Children. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32:406–12. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182040c22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bush M, Bianchi K, Lester C, et al. Delays in Diagnosis of Congenital Hearing Loss in Rural Children. Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;164(2):393–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bush M, Osetinsky M, Shinn JB, et al. Assessment of Appalachian Region Pediatric Hearing Healthcare Disparities and Delays. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(7):1713–7. doi: 10.1002/lary.24588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eleweke CJ, Rodda M. Factors contributing to parents’ selection of a communication mode to use with their deaf children. Am Ann Deaf. 2000;145(4):375–83. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hintermair M. Hearing impairment, social networks, and coping: The need for families with hearing impaired children to relate to other parents and to hearing-impaired adults. Am Ann Deaf. 2000;145(1):41–53. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korres SG, Balatsouras DG, Nikolopoulos T, Korres GS, Ferekidis E. Making universal newborn hearing screening a success. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2006;70:241–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. ASHA Practice Policy. Loss to Follow-Up in Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Working Group on Loss to Follow-Up Technical Report. Accessed May 24, 2016, at: http://www.asha.org/policy/TR2008-00302.htm#AP1.

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Cancer Institute. Theory at a Glance: A Guide For Health Promotion Practice. 2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and National Institutes of Health; 2005. Accessed May 31, 2016. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/cancerlibrary/theory.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient Navigation Research Program Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, Xie B. Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2007;44:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrante JM, Chen PH, Kim S. The effect of patient navigation on time to diagnosis, anxiety, and satisfaction in urban minority women with abnormal mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. J Urban Health. 2008;85:114–124. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raj A, Ko N, Battaglia T, et al. Patient navigation for underserved patients diagnosed with breast cancer. The Oncologist. 2012;17:1027–1031. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nash D, Azeez S, Vlahov D, Schori M. Evaluation of an intervention to increase screening colonoscopy in an urban public hospital setting. J Urban Health. 2006;83:231–243. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9029-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jandorf L, Gutierrez Y, Lopez J, Christie J, Itzkowitz SH. Use of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinic. J Urban Health. 2005;82:216–224. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen L, Santos S, Jandorf L, et al. A program to enhance completion of screening colonoscopy among urban minorities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bush M, Hardin B, Rayle C, Lester C, Studts C, Shinn J. Rural Barriers to Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Infant Hearing Loss in Appalachia. Otology & Neurotology. 2015;36(1):93–98. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calhoun EA, Whitley EM, Esparza A, et al. A national patient navigator training program. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11:205–15. doi: 10.1177/1524839908323521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jean-Pierre P, Fiscella K, Winters PC, Post D, et al. Psychometric development and reliability analysis of a patient satisfaction with interpersonal relationship with navigator measure: a multi-site patient navigation research program study. Patient Navigation Research Program Group. Psychooncology. 2012;21(9):986–92. doi: 10.1002/pon.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bush ML, Burton M, Loan A, Shinn JB. Timing discrepancies of early intervention hearing services in urban and rural cochlear implant recipients. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(9):1630–1635. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31829e83ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hands and Voices. Guide By Your Side. http://www.handsandvoices.org/gbys/. Accessed January 9, 2017.

- 37.Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. The history and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(15 0):3539–3542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elpers J, Lester C, Shinn J, Bush M. Rural Family Perceptions and Experiences with Early Infant Hearing Detection and Intervention: A Qualitative Study. J Community Health. 2016;41:226–233. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0086-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wittmann-Price RA, Pope KA. Universal newborn hearing screening. Am J Nurs. 2002;102(11):71–77. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200211000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Françozo MeF, Fernandes JC, Lima MC, Rossi TR. Improvement of return rates in a Neonatal Hearing Screening Program: the contribution of social work. Soc Work Health Care. 2007;44(3):179–190. doi: 10.1300/J010v44n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Percac-Lima S, Ashburner JM, McCarthy AM, Piawah S, Atlas SJ. Patient navigation to improve follow-up of abnormal mammograms among disadvantaged women. Journal of Women’s Health. 2015;24(2):138–143. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bensink ME, Ramsey SD, Battaglia T, et al. Costs and outcomes evaluation of patient navigation after abnormal cancer screening. Cancer. 2014:570–578. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wells KJ, Lee J, Calcano E, et al. A cluster randomized trial evaluating the efficacy of patient navigation in improving quality of diagnostic care for patients with breast or colorectal cancer abnormalities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(10):1664–1672. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramirez A, Perez-Stable E, Penedo F, et al. Reducing time-to-treatment in underserved Latinas with breast cancer. Cancer. 2014:752–760. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ell K, Padgett D, Vourlekis B, et al. Abnormal mammogram follow-up: a pilot study in women with low income. Cancer Practice. 2002;10(3):130–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.103009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paskett E, Katz ML, Douglas MP, et al. The Ohio patient navigation research program (opnrp): does the american cancer society patient navigation model improve time to resolution among patients with abnormal screening tests? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(10):1620–1628. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]