Abstract

Background:

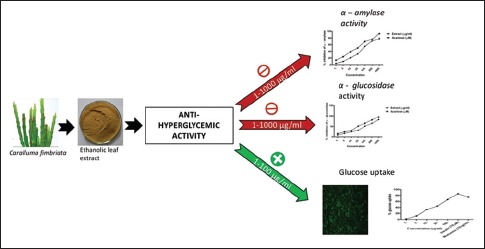

An increase in prevalence of diabetes mellitus necessitates the need to develop new drugs for its effective management. Plants and their bioactive compounds are found to be an alternative therapeutic approach. Caralluma fimbriata, used in this study, is well known for its various biological effects.

Objective:

The present study was designed to investigate the antihyperglycemic effect of the ethanolic leaf extract of C. fimbriata.

Materials and Methods:

Different concentrations (1–1000 mg/mL) of the ethanolic leaf extract of C. fimbriata were subjected to alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory assay with acarbose as control. Cytotoxicity was assessed by 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay. Glucose uptake assay was performed on L6 myotubes using the extract in 1 μg–100 μg/mL, using metformin and insulin as control.

Results:

The C. fimbriata extract showed potent inhibitory activity on enzymes of glucose metabolism in a dose-dependent manner. The maximum alpha-amylase inhibitory effect was 77.37% ± 3.23% at 1000 μg/mL with an IC50 value of 41.75 μg/mL and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory effect was 83.05% ± 1.69% at 1000 μg/mL with an IC50 value of 66.71 μg/mL. The maximum glucose uptake was found to be 66.32% ± 0.29% for the Caralluma extract at 100 μg/mL and that of metformin (10 μg/mL) was 74.44% ± 1.72% and insulin (10 mM) 85.55% ± 1.14%. The extract was found to be safe as the IC50 of extract and metformin was found to be ≥1000 μg/mL and ≥1000 μM, respectively, in the cell line tested.

Conclusion:

The study concludes that C. fimbriata has promising antihyperglycemic activity.

SUMMARY

Caralluma fimbriata extract exhibited effective dose dependent inhibitory activity against alpha-amylase and alpha- glucosidase

Enhanced glucose uptake from L6 myotubes was appreciated in the presence of the extract, comparable to Insulin and metformin

Caralluma fimbriata has potent antihyperglycemic properties.

Abbreviations used: GLUT: Glucose transporter; MTT: 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide.

Keywords: Alpha-amylase; alpha-glucosidase; Caralluma fimbriata; diabetes mellitus; glucose uptake; 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disorder steadily increasing prevalence worldwide. It is characterized by hyperglycemia with altered carbohydrate, protein, and lipid metabolism. This may be attributed to insulin inactivity or resistance, as a direct result of destruction or dysfunction of the beta-cells of the pancreas.[1] Diabetes is growing as an epidemic, with India emerging as the diabetic capital of the world. India is facing the burden of the consequences that the disease brings; it is currently estimated that every fifth diabetic in the world is an Indian.[2] Statistics reveals that by 2030, up to 79.4 million individuals, in India alone, will be afflicted with the disease.[3] Control of postprandial hyperglycemia is the key to the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications.[4] Conventional approaches include exogenous insulin administration and oral hypoglycemic agents such as alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, sulfonylureas, biguanides, thiazolidinediones, and meglitinides. Conventional approach to this growing epidemic is associated with many side effects, and moreover, it is expensive and inaccessible to certain communities.[5,6] In recent years, medicinal plants are explored to develop novel compounds and newer target as an ideal substitute to conventional drugs as there is an increasing demand for plant-based natural products. The Indian system of medicine is replete with plants, which have been shown to stimulate glucose uptake in the body and hence may be used for the long-term management of diabetes.[7]

Antihyperglycemic activity of several traditional Indian plants such as Aloe vera, Adhatoda zeylanica, and Brassica juncea[8] as well as fruits such as Eugenia jambolana (Jambul) and Psidium guajava L (Guava)[9] has been demonstrated.

Caralluma fimbriata (family Apocynaceae) is a wild succulent cactus found in dry regions of Tamil Nadu. It is known for its hypolipidemic, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, antiobesogenic, and anticancer activities with no history of adverse effects.[10,11,12] In this study, the ethanolic extract of C. fimbriata leaf was investigated for its antihyperglycemic activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and extract

The ethanolic extract of C. fimbriata leaf was obtained from Green Chem Herbal Extracts and Formulations, Bengaluru, as gratis. Alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase enzymes were obtained from Hi Media, Mumbai. L6 myoblast culture was obtained from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune. All other reagents and chemicals such as ethanol and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) used were of analytical grade.

Cell culture studies

Preparation of cell culture

L6 monolayer myoblast (obtained from NCCS, Pune – passage no. 15) was cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and supplemented with penicillin (120 units/mL), streptomycin (75 μg/mL), gentamicin (160 μg/mL), and amphotericin B (3 μg/mL) in a 5% CO2 environment. For differentiation, the L6 cells were transferred to DMEM with 2% FBS for 4 days, postconfluence. The extent of differentiation was established by observing the multinucleate of cells.

Cytotoxicity study-3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay (Gohel et al., 1999)

Cytotoxicity of the test extract was assessed by 3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay.[13] The plant extract was prepared in DMSO for the cytotoxicity study. Cells were plated in 48-well plate at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/well. After 24 h of incubation, it was washed with 200 ml of 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and starved by incubation in serum-free medium for an hour at 37°C in CO2 incubator. After starvation, cells were treated with different concentrations (1–1000 μg/mL) of the test extract for 24 h. At the end of the treatment, media from control and extract-treated cells were discarded, and 50 μl of MTT containing PBS (5 μg/mL) was added to each well. Cells were then incubated for 4 h at 37°C in CO2 incubator. The purple formazan crystals formed were then dissolved by adding 150 ml of DMSO and mixed effectively by pipetting up and down. Spectrophotometrical absorbance of the purple blue formazan dye was measured using multimode reader (Perkin Elmer) at 570 nm. Optical density of each sample was compared with control optical density and graphs were plotted.

6-(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl) amino)- 2-deoxyglucose assay-glucose uptake test

Antidiabetic activity of the test extract was assessed in differentiated L6 myotubes using fluorescent-tagged 6-(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol- 4-yl) amino)-2-deoxyglucose (6-NBDG). L6 myotubes (10,000 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and allow to confluence around 80%. Then, cells were differentiated using 2% FBS, and different concentrations of the extract dissolved in DMSO (1–100 μg/mL) were added. At the end of treatment, 10 μM of insulin was added to stimulate glucose uptake and incubated for 15 min. About 20 μg/200 mL of 6-NBDG was added and incubated for 10 min at dark. Glucose uptake (in %) was measured using multimode reader (Perkin Elmer) with an excitation/emission filter 466/540 nm.

In vitro alpha-amylase inhibitory assay (Bernfeld, 1955)

In vitro amylase inhibition was studied by the method of Bernfeld.[14] The plant extract was dissolved in ethanol. In brief, 100 μL of the test extract was allowed to react with 200 μl of alpha-amylase enzyme (Hi Media RM 638) and 100 μl of 2 mM of phosphate buffer (pH 6.9). After 20-min incubation, 100 μl of 1% starch solution was added. The same was performed for the controls where 200 μl of the enzyme was replaced by buffer. After incubation for 5 min, 500 μl of 3,5-Dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) reagent was added to both control and test. They were kept in boiling water bath for 5 min. The absorbance was recorded at 540 nm using spectrophotometer, and the percentage inhibition of alpha-amylase enzyme was calculated using the formula:

% inhibition = ([Control − Test]/Control) × 100

The reagent blank and inhibitor controls were simultaneously carried out.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity (Shruti et al., 2011)

The enzyme inhibition activity for alpha-glucosidase was evaluated according to the method previously reported by Sancheti et al. with minor modifications.[15] The plant extract was dissolved in ethanol. The reaction mixture consisted of 50 μL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (with pH of 7.0), 25 μL of 0.5 mM 4-nitrophenyl a-D-glucopyranoside (dissolved in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, with pH of 7.0), 10 μL of test extract, and 25 μL of alpha-glucosidase solution (a stock solution of 1 mg/mL in 0.01 M phosphate buffer, with pH of 7.0, was diluted to 0.1 unit/mL with the same buffer, with pH of 7.0 just before assay). This reaction mixture was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Then, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 μl of 0.2 M sodium carbonate solution. The enzymatic hydrolysis of substrate was monitored by the amount of p-nitrophenol released in the reaction mixture at 410 nm using microplate reader. Individual blanks were prepared for correcting the background absorbance, where the enzymes were replaced with buffer. Controls were conducted in an identical manner replacing the plant extracts with methanol. Acarbose was used as positive control.

Statistical analysis

The experiments were carried in triplicate and all the values were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Microsoft Excel 2016 was used to perform linear regression and correlation analysis.

RESULTS

Cytotoxicity assay

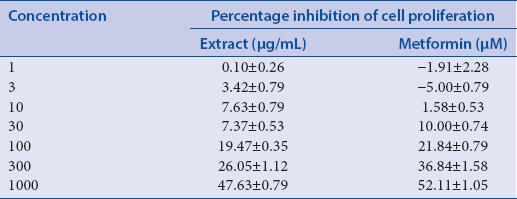

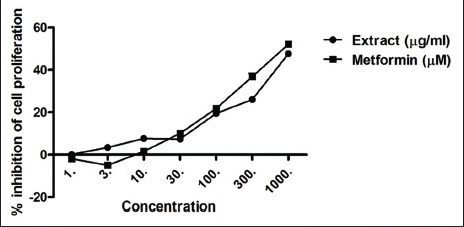

The cytotoxicity assay was carried out for the extract at different concentrations of 1–1000 μg/mL at time interval of 24 h. From the results, it was observed that both extract and standard metformin have exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in the percentage cell proliferation which was <50% even at a maximum dose of 1000 μg/mL. The IC50 of extract and metformin was found to be ≥1000 μg/mL and ≥1000 mM, respectively [Table 1 and Graph 1].

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity (3-[4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay of test extract using L6 myotubes

Graph 1.

Graphical representation of cytotoxicity (3-(4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay of test extract using L6 myotubes

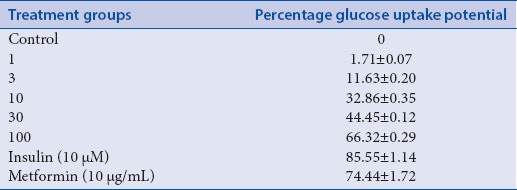

6-(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl) amino)- 2-deoxyglucose glucose uptake in L6 myotubes

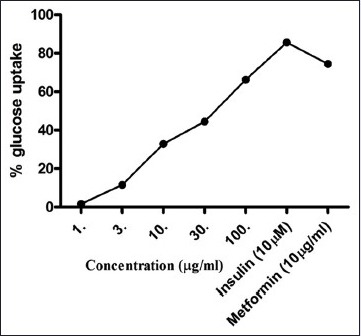

The nonmetabolizable fluorescent glucose analog 6-NBDG is increasingly used to study cellular transport of glucose. Intracellular accumulation of exogenously applied 6-NBDG is assumed to reflect concurrent gradient-driven glucose uptake by glucose transporters (GLUTs). The glucose uptake potential of the extract was evaluated at different concentrations of 1–100 μg/mL. The plant extract was dissolved in DMSO. Insulin (10 μM) and standard metformin (10 μg/mL) were used as positive controls. It was shown from the results that the extract has enhanced glucose uptake in L6 myotubes in a dose-dependent manner which was compared with standard metformin. The maximum percentage of uptake was found to be 66.32% ± 0.29% for the extract while metformin at 10 μg/mL exhibited 74.44% ± 1.72% and insulin showed 85.55% ± 1.14% of glucose uptake [Table 2, Graph 2 and Figures 1–5].

Table 2.

(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)-2-deoxyglucose glucose uptake potential of test extract in L6 myotubes

Graph 2.

Graphical representation of 6-(N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)-2-deoxyglucose glucose uptake potential of test extract in L6 myotubes

Figure 1.

Caralluma extract 10 μg/ml

Figure 5.

Insulin 10 μM

Figure 2.

Caralluma extract 30 μg/ml

Figure 3.

Caralluma extract 100 μg/ml

Figure 4.

Metformin 10 μg/ml

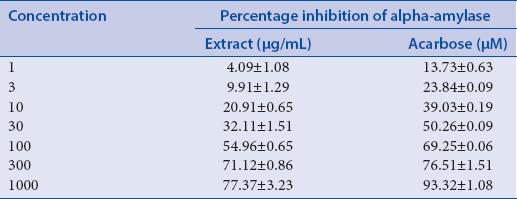

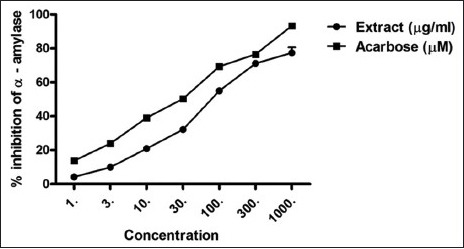

Alpha-amylase inhibitory activity

The results showed strong alpha-amylase inhibitory activity of the test extract which is compared with standard acarbose. A maximum inhibition of 77.37% ± 3.23% was achieved at a concentration of 1000 μg/mL by test extract while standard acarbose inhibition was about 93.32% ± 1.08%. The IC50 of the extract was found to be 41.75 μg/mL and for acarbose 34.83 μM [Table 3 and Graph 3].

Table 3.

Alpha-amylase inhibitory activity of test extract

Graph 3.

Graphical representation of alpha-amylase inhibitory activity of test extract

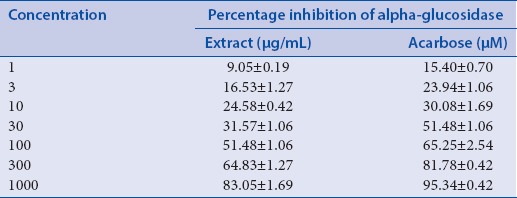

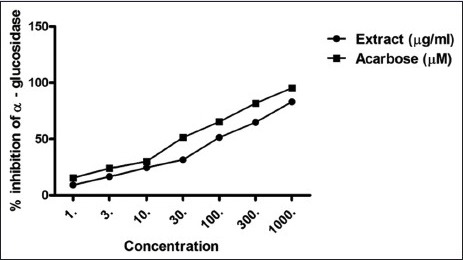

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity

The in vitro alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the test extract was investigated. The maximum inhibition of the extract was found to be 83.05% ± 1.69% at 1000 μg/mL which is comparable with that of standard acarbose which showed its maximum inhibition of 95.34% ± 0.42% at 1000 μM. The IC50 of the extract and acarbose was found to be 66.71 μg/mL and 45.69 μg/mL, respectively [Table 4 and Graph 4].

Table 4.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity of test extract

Graph 4.

Graphical representation of alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity of test extract

DISCUSSION

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder with several life-threatening complications which may be microvascular such as retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy or macrovascular such as peripheral vascular disease, heart attack, and stroke. Among the two types, type 2 or noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is the most common and accounts for 90%–95% of diabetic mellitus cases.[16] The management of postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetic patients is crucial to prevent complications and to have a positive impact on morbidity and mortality rates associated with the disease. Plant-based drugs are found to be safer hypoglycemic agents compared to synthetic chemical alternatives available in the market.

Within the Caralluma genus, Caralluma tuberculata, Caralluma lasiantha, Caralluma edulis, Caralluma sinaica, and Caralluma umbellata Haw have all been proven to have antidiabetic properties.[17,18,19] Phytochemical studies reveal polyphenols, which may be suggestive of its antihyperglycemic activity.[19] The ethanolic leaf extract of C. fimbriata showed its ability to inhibit the activity of enzymes of carbohydrate digestion, alpha-amylase, and alpha-glucosidase. It also increased the uptake of glucose by the L6 myotubes. The glucose uptake activity was comparable to the activity of insulin (injectable antidiabetic drug) and metformin (oral antidiabetic drug).

The skeletal muscle forms the quantum of the body's musculature and is a major site of glucose uptake and utilization, mediated by insulin.[20] An intracellularly sequestered insulin-responsive GLUT called GLUT-4 forms an important component of this insulin signal transduction pathway. Insulin regulates the release of GLUT-4 from storage pools and promotes its rapid translocation to the plasma membrane, thus enhancing muscle cell glucose uptake.[21,22] Defective glucose uptake by muscle cells is a common pathological state in type 2 diabetes mellitus due to deficient insulin; various in vitro glucose uptake models have shown that certain medical plants enhance glucose uptake by GLUT-4 translocation.[20,23,24,25] Results of this study demonstrate enhanced glucose uptake by L6 myotubes in the presence of ethanolic leaf extract of C. fimbriata. Hence, it may be hypothesized that ethanolic leaf extract of C. fimbriata may work by a similar mechanism. The rationale behind using L6 cell lines to elucidate the glucose uptake mechanism is that they have intact insulin-signaling pathways and express insulin-sensitive GLUT-4.[25]

This study has also demonstrated a potent dose-dependent inhibitory effect of alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase enzymes of carbohydrate digestion. These enzymes work on the principle of hydrolysis; alpha-amylase breaks down polysaccharides such as starch and glycogen to disaccharides and alpha-glucosidase catalyzes this further to monosaccharide, thus increasing blood glucose levels.[26]

Inhibition of these key enzymes involved in glucose metabolism is an effective strategy to combat postprandial hyperglycemia. Traditional drugs in the market such as acarbose and miglitol work by inhibiting this membrane bound enzymes along the brush border of the small intestine, thus retarding glucose absorption. However, these drugs result in gastrointestinal intolerance.[27] Plant products have been proven as attractive alternatives, with many of them showing significant enzyme inhibitory activity.[26,28,29,30] It may be suggested that the extracts of C. fimbriata work with a mechanism of action similar to acarbose, but further studies are warranted to elucidate the exact mode of inhibition and the bioactive compounds responsible for it. However, the extract showed protective effect even at higher concentrations, 1000 μg/mL, and the IC50 value was more than 1000 μg/mL.

CONCLUSION

The current study revealed that the ethanolic leaf extract of C. fimbriata has pronounced glucose uptake potential as well as potent inhibitory activity on enzymes of glucose metabolism, alpha-amylase, and alpha-glucosidase, proving its antihyperglycemic activity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nayak BS, Roberts L. Relationship between inflammatory markers, metabolic and anthropometric variables in the Caribbean type 2 diabetic patients with and without microvascular complications. J Inflamm (Lond) 2006;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar A, Goel MK, Jain RB, Khanna P, Chaudhary V. India towards diabetes control: Key issues. Australas Med J. 2013;6:524–31. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2013.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaveeshwar SA, Cornwall J. The current state of diabetes mellitus in India. Australas Med J. 2014;7:45–8. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2013.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai TT, Khoo CS, Tee CS, Wong FC. Alpha glucosidase inhibitory and antioxidant potential of antidiabetic herb Alternanthera sessilis: Comparitive analysis of leaf and callus solvent fractions. Pharmacogn Mag. 2016;12:253–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.192202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kibiti CM, Afolayan AJ. Herbal therapy: A review of emerging pharamacological tools in management of diabetes mellitus in Africa. Pharmacogn Mag. 2015;11(Suppl S2):258–74. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.166046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sosa G, Roy A. Novel approaches in insulin drug delivery - A review. Int J Drug Dev Res. 2013;5:25–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar BD, Krishnakumar K, Jaganathan SK, Mandal M. Effect of Mangiferin and Mahanimbine on glucose utilization in 3T3-L1 cells. Pharmacogn Mag. 2013;9:72–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.108145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khera N, Bhatia A. Medicinal plants as natural anti diabetic agents. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2014;5:713–29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy A, Geetha RV, Lakshmi T, Nallanayagam M. Edible fruits - Nature's gift for diabetic patients - A comprehensive review. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2011;9:170–80. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashwini S, Ezhilarasan D, Anitha R. Cytotoxic effect of Caralluma fimbriata against human colon cancer. Pharmacogn J. 2017;9:204–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latha S, Rajaram K, Suresh Kumar P. Hepatoprotective and antidiabetic effect of methanol extract of Caralluma fimbriata in streptatozocin induced diabetic albino rats. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6:665–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudhakara G, Mallaiah P, Sreenivasulu N, Sasi Bhusana Rao B, Rajendran R, Saralakumari D, et al. Beneficial effects of hydro-alcoholic extract of Caralluma fimbriata against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and oxidative stress in Wistar male rats. J Physiol Biochem. 2014;70:311–20. doi: 10.1007/s13105-013-0304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gohel A, McCarthy MB, Gronowicz G. Estrogen prevents glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in osteoblasts in vivo and in vitro. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5339–47. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernfeld P. Amylases a and b. In: Colowick SP, Kaplan ND, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press Inc. Publishers; 1955. pp. 149–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sancheti S, Sancheti S, Lee SH, Lee JE, Seo SY. Screening of Korean medicinal plant extracts for a -glucosidase inhibitory activities. Iran J Pharm Res. 2011;10:261–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel DK, Prasad SK, Kumar R, Hemalatha S. An overview on antidiabetic medicinal plants having insulin mimetic property. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2:320–30. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60032-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harish Kumar VS. Anti hyperglycemic effect of Caralluma lasiantha extract on hyperglycemia induced by cafeteria diet in experimental model. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2016;7:2525–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdel-Sattar EA, Abdullah HM, Khedr A, Ashraf B, Naim A, Shehata IA. Antihyperglycemic activity of Caralluma tuberculata in Streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;59:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellamkodi PK, Godavarthi A, Ibrahim M. Antihyperglycemic actvity of Caralluma umbellata Haw. Bioimpacts. 2014;4:113–6. doi: 10.15171/bi.2014.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathews AM, Sujith K, Pillai S, Christina AJ. Study of glucose uptake activity of Solanum xantohocarpum in l-6 cell lines. Eur J Biol Sci. 2013;5:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajeswari R, Sriidevi M. Study of in vitro glucose uptake activity of isolated compounds from hydro alcoholic leaf extract of Cardiospermum halicacabum linn. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6:181–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SY, Kim MH, Ahn JH, Lee SJ, Lee JH, Eum WS, et al. The stimulatory effect of essential fatty acids on glucose uptake involves both Akt and AMPK activation in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;18:255–61. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.3.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudharshan Reddy D, Srinivasa Rao A, Pradeep Hulikere A. In vitro antioxidant and glucose uptake effect of Trichodesma indicum in L-6 cell lines. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2012;3:810–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yarasu N, Smana P, Pavankumar R, Nareshchandra RN, Vinil Kumar V. In vitro glucose uptake assay of hydro methanolic leaves extract of Syzygium jambos (L) Alston in rat skeletal muscle (L6) cell lines. Indo Am J Pharm Res. 2013;3:7336–41. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shoba Das M, Devi G. In vitro cytotoxicity and glucose uptake activity of fruits of Terminalia bellirica in vero, L-6 and 3T3 cell lines. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2015;5:92–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Telagari M, Hullatti K. In-vitro a -amylase and a -glucosidase inhibitory activity of Adiantum caudatum Linn. and Celosia Argentea Linn. extracts and fractions. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47:425–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.161270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tabatabaei-Malazy O, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. Targeting metabolic disorders by natural products. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:57. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0184-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy A, Geetha RV. In vitro a -amylase and a -glucosidase inhibitory activities of the ethanolic extract of Dioscorea villosa tubers. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2013;4:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganeshpurkar A, Diwedi V, Bhardwaj Y. In vitro a -amylase and a -glucosidase inhibitory potential of Trigonella foenum-graecum leaves extract. Ayu. 2013;34:109–12. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.115446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ademiluyi AO, Oboh G. Soybean phenolic-rich extracts inhibit key-enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes (a -amylase and a -glucosidase) and hypertension (angiotensin I converting enzyme)in vitro. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2013;65:305–9. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]