Abstract

Purpose of review:

Functional movement disorders (FMD) are commonly seen in neurologic practice, but are associated with poor outcomes. Recent years have seen a resurgence of interest in this area, with new developments in pathophysiologic understanding and therapeutic management.

Recent findings:

Individuals with FMD are a psychologically heterogeneous group, with many individuals having no detectable psychopathology on symptom screening measures, and possibly significant etiologically relevant life events only revealed through in-depth interviews. A randomized trial of specialist intensive physical rehabilitation compared to community-based neurophysiotherapy in FMD has demonstrated moderate to large effect sizes for both physical and social functioning outcomes. Experimental evidence suggests an impairment in the neural systems conferring a sense of agency over movement in individuals with FMD, and may explain why movements that appear voluntary are not experienced as such.

Summary:

The prognosis of individuals with FMD may be improved with greater access to appropriately organized care and treatment.

Functional movement disorders (FMD) are abnormalities of movement that are altered by distraction or nonphysiologic maneuvers, and are clinically incompatible with movement disorders associated with neurologic disease. FMD are a common presentation of the wider category of functional neurologic disorder. Functional disorders are extremely common in neurologic practice, with one study demonstrating that functional neurologic disorder accounted for 15% of new referrals seen in neurology clinics, second only to headache.1 Despite their common occurrence, prognosis is poor, with a systematic review finding that 39% of patients were the same or worse on long-term follow-up, with high levels of physical disability and psychological comorbidity.2 Individuals diagnosed with FMD have traditionally been left in a therapeutic wasteland, with neither neurologist nor psychiatrist able to provide strategies to bring about symptom resolution.

There have been a number of recent advances in the field of FMD, including not only a rebranding of its name, but a deeper understanding of pathophysiologic aspects of the condition, and most importantly, a pathway to successful treatment. We highlight here some rays of light in a dark landscape, providing a sense of optimism to an area long equated with frustration for both patients and their care providers.

What's in a name?

There has been recent debate in the literature with respect to the term psychogenic movement disorders, with a broader term, functional movement disorders, suggested to take its place.3,4 The main argument for this rebranding is that the term psychogenic implies that the etiology of the symptoms is understood as being born of the mind. However, diagnosis is made with reference to positive symptoms and signs and not on the presence of psychopathology. A psychological trigger is not possible to establish in many patients, though it is difficult to be sure if this is because it is not present or simply not recognized. The term functional has been proposed as being freer from etiologic assumptions and recognizes that the cause of these symptoms may not be evident. Functional is the second most common term used between colleagues specializing in movement disorders, and is a term used without controversy in other areas of medicine.3 Importantly, publication of the DSM-5 brought about changes to the criteria for conversion disorder, including its name, which now includes functional neurologic symptom disorder in parentheses. The DSM-5 criteria have also been modified to emphasize the importance of the neurologic examination, and that relevant psychological factors may not be present. Specifically, clinical findings should provide evidence of incompatibility between the symptom and a recognized neurologic condition.

Psychological factors

Researchers continue to explore the psychological underpinnings of FMD, with recent studies seeking to confirm the Freudian hypothesis of conversion, and conversely, to validate the removal of criteria for psychological stressors from DSM-5. A case-control study of 51 individuals with FMD evaluated self-rated measures of depression, anxiety, dissociation, and personality disorders compared to individuals with neurologic (organic) movement disorders and healthy controls.5 Thirty-nine percent of individuals with FMD scored in the normal range on all psychological questionnaires, compared to 38% of individuals with neurologic movement disorders and 89% of controls. Patients with FMDs had similar scores as patients with neurologic movement disorders for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological dissociative symptoms, and only differed on symptoms of somatic dissociative symptoms. The study concluded that individuals with FMD are not different psychologically from individuals with neurologic movement disorders, and that a relevant proportion of individuals with FMD have no psychopathology detectable on symptom screening measures.

Using the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule, Nicholson et al.6 evaluated severe life events (life events associated with a long-term marked or moderate threat) and escape events (the extent to which the effect of a stressor might be ameliorated by being ill with neurologic symptoms) in the year preceding symptom onset in 43 individuals with motor conversion disorder (motor symptoms thought to be psychological in origin), 28 individuals with depression, and 28 healthy controls. Fifty-six percent of individuals with conversion disorder had at least one severe event in the month before symptom onset, significantly more compared to 21% of individuals with depression (odds ratio [OR] 4.63) and 18% of healthy controls (OR 5.81). Fifty-three percent of patients with conversion disorder had a least one high escape event, which was significantly higher than in those with depression (14%) and healthy controls (0%). The majority of etiologically relevant life events were not detected on routine assessment, suggesting that in-depth and specific interviewing skills are necessary to reveal these events. Whether these life events represent transient triggers or important maintaining factors in symptoms (and therefore of treatment relevance) remains uncertain.

Overall, these findings point to the heterogeneous psychological background to patients with FMD. A simplistic approach to diagnostic explanation and treatment (“this has happened because of stress, you need to see a psychologist”) fails to acknowledge this complexity. A sensitive and open-minded exploration of psychological factors potentially conferring vulnerability to develop FMD and maintenance of symptoms is useful and should be part of an individualized approach to diagnostic explanation and treatment. This exploration may well find no relevant factors, or find factors that have conferred vulnerability but are not currently active, and explanation of diagnosis and treatment needs to have the flexibility to accommodate these common situations.

Loss of sensory attenuation

A major issue in attitudes towards patients with FMD is a doubt as to whether the symptoms might be voluntarily, deliberately produced. After all, the movements seen in many people with FMD have characteristics associated with voluntary movement, for example distractibility. If patients are by and large telling the truth, then one explanation could be that the system that confers sense of agency over movement is impaired in patients with FMD. There are other situations in neurology and psychiatry where movements that appear voluntary are not experienced as such, for example alien limb and anarchic hand syndromes and delusions of control in schizophrenia. Disordered function of systems conferring sense of agency for movement are commonly suggested to explain such phenomena. Sensory attenuation is a phenomenon whereby the intensity of sensation caused by self-generated movements is reduced. Sensory attenuation is believed to be important in labeling movements as self-generated, and a loss of sensory attenuation has been associated with a loss of agency for movement,7 and has previously been reported to be abnormal in patients with schizophrenia with delusions of control.8 An investigation of sensory attenuation in individuals with FMD was recently performed using a force matching paradigm.9

In the force matching paradigm, participants are asked to match a force delivered to the finger by pressing directly onto the finger with the other hand (the self condition), or by operating a joystick that causes a robot to press down on the finger (the external condition). Healthy participants consistently generate more force than necessary during the self condition—due to the phenomenon of sensory attenuation—compared with the external condition. Individuals with FMD are much more accurate than healthy controls in their force estimation performance in the self condition. Performance between the 2 groups did not differ for the external condition. This difference in performance between the 2 groups is thought to be due to a loss of sensory attenuation in individuals with FMD, which may reflect a lack of agency for self-generated movements. The authors propose that a generalized increase in body-focused attention in patients with FMD means that they do not attenuate the sensory consequences of their actions, and that this makes them more likely to lose sense of agency for their actions.

Neuroimaging

Previous functional imaging studies in patients with FMD have found evidence for temporoparietal junction hypofunction—this area is thought to be important in comparing actual with expected sensory feedback during movement, and hence in sense of agency for movement. Abnormal connectivity between motor and limbic areas has also been demonstrated.10,11

Researchers have attempted to examine the neural correlates of recall of life events judged to be of causal significance in individuals with conversion disorder, following the Freudian hypothesis of repression of psychological conflict and conversion of symptoms to physical disability in individuals with functional disorders.12 Using the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule to identify severe life events and escape events (as described above) in 12 individuals with conversion disorder and 13 controls, the researchers obtained details about severe life events, escape events, and a neutral event from the same time period to generate 72 statements. Twenty-five percent of the statements were made incorrect by changing details, to maximize immersive recall when later asked in the fMRI setting if statements were true or false. Blocks of 8 statements were presented in random order by condition (severe, escape, neutral), for which participants had to respond if each statement was true or false. Reaction times for true or false responses were recorded, and participants were asked to rate how upsetting the block of statements was using a visual analogue scale. Functional MRI during recall of the escape condition relative to the severe condition in patients vs controls revealed increased activity in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, with decreased hippocampal and parahippocampal activity, a pattern compatible with memory suppression. Escape events also elicited significantly longer reaction times than neutral events and were perceived as less upsetting than severe events, though they were matched in threat level. These changes were accompanied by an increase in activity in the right supplementary motor cortex and right temporal parietal junction, areas involved in motor execution and sensory integration.

Overall these studies help to establish the underlying neural correlates of FMD, as well as the way in which etiologic factors, such as life events, might influence the underlying neurobiology of the disorder.

Therapeutic advance: Specialist physiotherapy

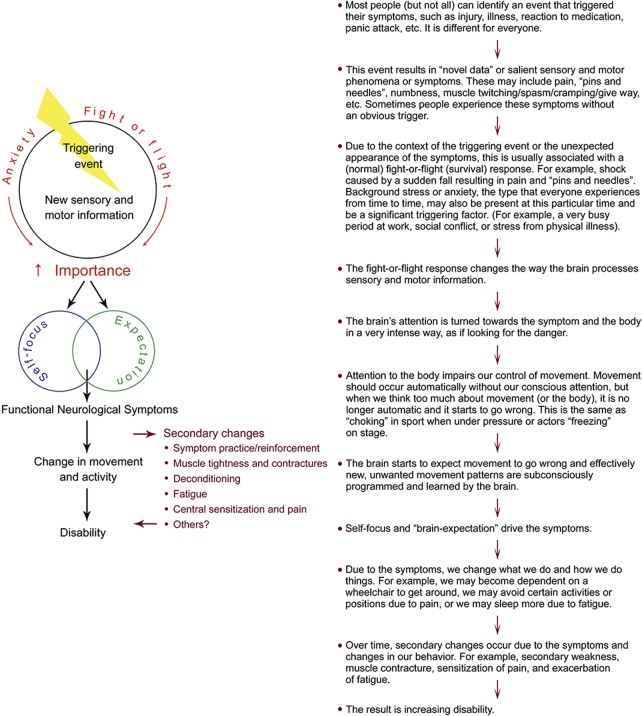

Nielsen et al.13 described a pilot 5-day specialist physiotherapy program for individuals with FMD, focusing on education, movement retraining, and long-term self-management. As a foundation, a pathophysiologic model of FMD was presented and taught to participants (figure). Patients engaged in a collaborative discussion of how their symptoms started and progressed, considering both physical and psychological triggers, as well as factors that may have perpetuated symptoms. Mirrors and video recordings were used to help explore movements and identify strategies to normalize movement patterns. Patients were guided by a physiotherapist to use these strategies in progressively more difficult tasks. This program was subsequently compared to treatment as usual (community-based neurophysiotherapy) in a randomized feasibility trial.14 Sixty participants were randomly allocated to the 5-day specialist program or to referral to a local physiotherapy service. At 6 months follow-up, individuals allocated to the specialist program had superior scores compared to the control group in the Physical Function, Physical Role, and Social Function domains of the Short Form–36, the Berg Balance Scale, the 10-meter walk time, the Functional Mobility Scale, the Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand scale, and the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire, with medium to large effect sizes (d = 0.46–0.79). Seventy-two percent of those receiving the specialist program reported a good outcome, compared to 18% in the control group. Measures of mental health did not change in either group, suggesting that physical function can be improved in individuals with FMD without changes in mental health symptoms.

Figure. Triggering events.

This study adds to previous work in indicating that specialist physical rehabilitation can be helpful in some patients with FMD. Consensus guidelines support this approach,15 and emphasize the need for good diagnostic explanation and patient selection in ensuring good outcome. Patients with active untreated psychopathology or with severe pain and fatigue as dominant symptoms may be less suitable for this high-intensity treatment. It is notable that most patients included in published studies of specialist physiotherapy for FMD had already received physiotherapy previously, often on multiple occasions, without benefit. This argues against a simple face-saving explanation for the benefit of physiotherapy (i.e., that getting better with a physical intervention is more socially/personally acceptable than improvement with a psychological intervention) and instead suggests that there are specific physical rehabilitation techniques that are useful in this patient group.

DISCUSSION

This selection of recent work in patients with FMD is part of a wider development of scientific and clinical interest in patients with functional neurologic symptoms in general. This is to some extent a redevelopment of interest in what was a major topic of neuroscientific interest in the mid to late 19th century. Underpinning it all is a large group of patients with neurologic symptoms, often disabling and impairing to quality of life, who lack access to organized care and treatment.

The work presented here emphasizes that it is the neurologist who should take on the responsibility for caring for patients with functional neurologic disorder, including FMD. These patients present with neurologic symptoms, the diagnosis is made on the basis of positive symptoms and signs by a neurologist, and the patient expects a diagnostic explanation from the neurologist. Given this, the neurologist is ideally placed to coordinate care and to take on long-term follow-up of patients with functional neurologic disorder. As with many other common neurologic conditions, treatment may involve other professionals, including mental health professionals, but the neurologist can have an important coordinating role.

The hope is that renewed interest in FMD and its treatment reviewed here will bring with it a new evidence base for management. There might therefore be hope for a better future for patients and their families with this important cause of neurologic disability.

Functional movement disorders: Five new things

Preferential use of the term functional movement disorders is proposed as being freer from etiologic assumptions and recognizes that the cause of symptoms may not be evident.

Patients with functional movement disorders have heterogeneous psychological backgrounds.

Specific physical rehabilitation techniques can be helpful in improving physical and social function in individuals with functional movement disorders.

Experimental evidence suggests that individuals with functional movement disorders do not attenuate the sensory consequences of their actions, and that this may reflect their lack of sense of agency for their actions.

Functional MRI during recall of life events judged to be of causal significance in individuals with conversion disorder reveals increased activity in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, with decreased hippocampal and parahippocampal activity, a pattern compatible with memory suppression.

Footnotes

See editorial, page 96

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Tamara Pringsheim wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Mark Edwards edited and revised the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

T. Pringsheim serves on the Editorial Boards of Neurology: Clinical Practice and Canadian Journal of Psychiatry and receives research support from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Sick Kids Foundation, and Alberta Mental Health Strategic Clinical Network. M. Edwards serves on scientific advisory boards for Cure Parkinson's Trust, UK Dystonia Society, and Medical Research Council; has received funding for travel and accommodation from the Movement Disorder Society and Merz Pharma; receives publishing royalties for Oxford Specialist Handbook of Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders (Oxford University Press, 2008); and receives research support from Medical Research Council NIHR (UK) and Parkinson's UK Dystonia Society. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stone J, Carson A, Duncan R, et al. . Who is referred to neurology clinics? The diagnoses made in 3781 new patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2010;112:747–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelauff J, Stone J, Edwards M, Carson A. The prognosis of functional (psychogenic) motor symptoms: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards MJ, Stone J, Lang AE. From psychogenic movement disorder to functional movement disorder: it's time to change the name. Mov Disord 2014;29:849–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fahn S, Olanow CW. “Psychogenic movement disorders”: they are what they are. Mov Disord 2014;29:853–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Hoeven RM, Broersma M, Pijnenborg GH, et al. . Functional (psychogenic) movement disorders associated with normal scores in psychological questionnaires: a case control study. J Psychosom Res 2015;79:190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson TR, Aybek S, Craig T, et al. . Life events and escape in conversion disorder. Psychol Med 2016;46:2617–2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blakemore SJ, Wolpert D, Frith C. Why can't you tickle yourself? Neuroreport 2000;2000:R11–R16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blakemore SJ, Smith J, Steel R, Johnstone CE, Frith C. The perception of self produced sensory stimuli in patients with auditory hallucinations and passivity experiences: evidence for a breakdown in self monitoring. Psychol Med 2000;30:1131–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parees I, Brown H, Nuruki A, et al. . Loss of sensory attenuation in patients with functional (psychogenic) movement disorders. Brain 2014;137:2916–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voon V, Brezing C, Gallea C, Hallett M. Aberrant supplementary motor complex and limbic activity during motor preparation in motor conversion disorder. Mov Disord 2011;26:2396–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, Bruno M, Ekanayake V, Hallett M. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology 2010;74:223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aybek S, Nicholson TR, Zelaya F, et al. . Neural correlates of recall of life events in conversion disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen G, Ricciardi L, Demartini B, Hunter R, Joyce E, Edwards MJ. Outcomes of a 5-day physiotherapy programme for functional (psychogenic) motor disorders. J Neurol 2015;262:674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen G, Buszewicz M, Stevenson F, et al. . Randomised feasibility study of physiotherapy for patients with functional motor symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Epub 2016 Sep 30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Nielsen G, Stone J, Matthews A, et al. . Physiotherapy for functional motor disorders: a consensus recommendation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:1113–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]