Practical Implications

Neurosyphilis is a treatable cause of stroke usually considered in young people, but also can occur in the elderly. Contrast-enhanced MRI findings are important in suggesting an infectious etiology in stroke patients of all ages.

We report an unusual case of meningovascular neurosyphilis with basilar artery enhancement secondary to syphilitic arteritis in an elderly man with HIV coinfection.

Case report

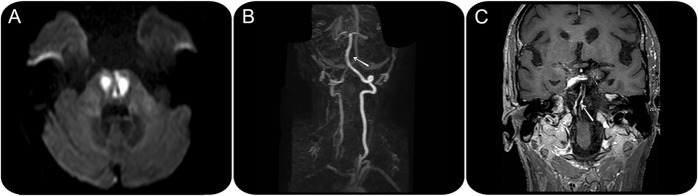

A 67-year-old hypertensive man presented with sudden gait instability and dysarthria. No other risk factors for ischemic stroke were present. Neurologic examination confirmed a marked gait unsteadiness, left facial paresis, dysarthria, left hemiparesis, incoordination of upper left limb and bilateral lower limbs, and bilateral Babinski sign. During the first 24 hours, he became somnolent and developed tetraparesis. Brain MRI showed an acute ischemic lesion in the pons (figure 1A) without supra-aortic vessel stenosis on magnetic resonance angiography (figure 1B), and with concentric enhancement of the basilar artery, consistent with arterial inflammation (figure 1C). The aortic arch was normal (not shown).

Figure 1. Diffusion-weighted brain MRI.

Brain MRI (diffusion sequence) shows an acute ischemic lesion involving the paramedian region of the pons (A). MRI angiography does not disclose any arterial stenosis of the supra-aortic vessels (B; the arrow signals the basilar artery), but contrast-enhanced MRI sequences show a long, concentric enhancement of the basilar artery wall (C, arrow), consistent with vasculitis.

Laboratory tests revealed positive serum nontreponemal (rapid plasma reagin [RPR] titer of 1/2,048) and treponemal tests as well as HIV antibodies (viral load of 36,100 copies/mL). CD4 count was 102 cells/mm3, CD8 count 449 cells/mm3, and CD3 count 557 cells/mm3. Lumbar puncture showed a pleocytosis of 16 cells/mm3, proteins of 198 mg/dL, and normal glucose. Both treponemal and nontreponemal tests were also positive in the CSF.

The patient denied risk factors for meningovascular syphilis and HIV. He was started on highly active antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), and received a course of 2 weeks of IV ceftriaxone (2 g daily).

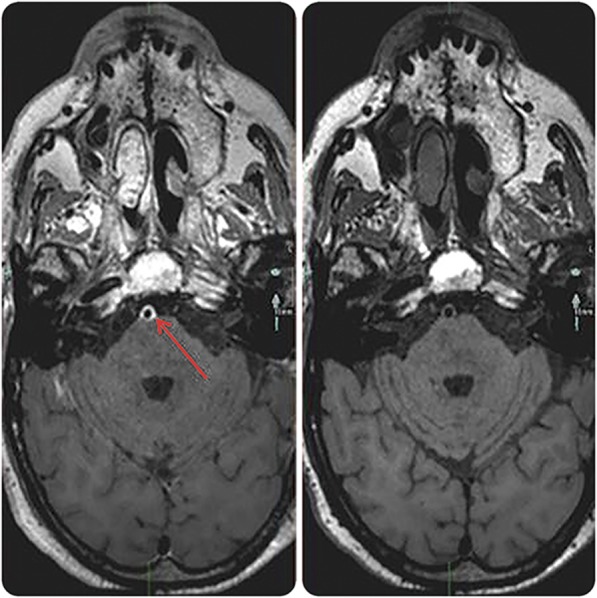

The patient improved considerably, but was left with upper left limb paresis and paraparesis. He was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. Follow-up brain MRI 3 months later showed a resolution of the basilar enhancement (figure 2).

Figure 2. Contrast-enhanced brain MRI.

Contrast-enhanced MRI before (left) and 3 months after therapy (right) shows the resolution of the arterial enhancement (arrow pointing at the basilar artery).

DISCUSSION

Cerebral ischemia due to meningovascular syphilis is rare, more frequently involving the anterior circulation, and occurs as a result of an obliterative endarteritis of medium- and large-sized vessels. Neurosyphilis has been reported as a cause of stroke in a young adult without cerebrovascular risk factors and with a prodromal phase of weeks to months of headaches, malaise, and personality changes.1 Syphilis accounted for 4.1% of all acute stroke patients in a hospital-based study conducted in Sudan,2 and stroke accounted for about 10% of neurosyphilitic presentations in 241 patients in one US hospital.3

Neurosyphilis is generally considered in young stroke patients only. Our case raises the issue of whether syphilis serology should be included in all stroke patients and not only in those considered at risk.4 The patient we describe was in his late 60s, an age at which atherothrombotic stroke is common, had hypertension, and presented with a stroke involving the posterior brain circulation without prodromal symptoms. He denied any risk factors for sexually transmitted diseases, even after syphilis had been diagnosed. Had serology not been performed, the diagnosis, therapy, and preventive interventions would not have been provided. Further, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) in the CSF is specific enough to establish a diagnosis of neurosyphilis and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-Abs) is sufficiently sensitive that a negative FTA-Abs practically excludes neurosyphilis whereas a positive VDRL practically confirms it.5 A clue to the diagnosis of this patient was provided by the MRI findings, which showed enhancement of the basilar artery without the presence of atherosclerotic plaques or vessel occlusion. Wall enhancement can occasionally be seen in atherothrombotic disease, but associated with plaques and vessel stenosis.6 A 68-year-old patient with stroke and syphilis has been reported, but unlike the case presented here, he had a history of primary syphilis.7 One report described an 80% rate of misdiagnosis among HIV-negative neurosyphilis patients presenting with stroke in the Emergency Department.8 The importance of angiography in confirming the diagnosis of syphilitic arteritis was underscored by another report.9 Consistent with our patient, a study has found that among HIV-infected patients with newly diagnosed syphilis, risk factors for developing neurosyphilis included being a man, a CD4 count of <350 cells/mm3, and an RPR titer >1:128.10

Our patient was HIV-positive and met the criteria for AIDS definition on the basis of a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3. HIV infection confers an increased risk for stroke11,12 and thus could have contributed to this patient's vasculopathy, and shortens the latency period from primary syphilis to neurosyphilis.13

Coinfection with AIDS and syphilis is frequent because of shared risk factors. Despite the recent decrease in the rate of new HIV infections (50% decrease in 50 countries around the world),14 intense vigilance should be maintained to avoid missing these treatable disorders, and to stop transmission in sexually acquired diseases. Recent studies recommend that, due to the reemergence of syphilis, search for Treponema pallidum infection should be systematic in young stroke victims.15 The question remains as to whether the search should include all-age patients even in the absence of a suggestive history.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Drs. Ruisánchez, Anguizola, García-Gorostiaga, Vicente-Olabarria, Escalza-Cortina, Gomez-Beldarrain, and Garcia-Monco were involved in the clinical care of this patient and participated in writing the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

The authors report no disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holmes MD, Brant-Zawadzki MM, Simon RP. Clinical features of meningovascular syphilis. Neurology 1984;34:553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sokrab TE, Sid-Ahmed FM, Idris MN. Acute stroke type, risk factors, and early outcome in a developing country: a view from Sudan using a hospital-based sample. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2002;11:63–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooshmand H, Escobar MR, Kopf SW. Neurosyphilis: a study of 241 patients. JAMA 1972;219:726–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelley RE, Bell L, Kelley SE, Lee SC. Syphilis detection in cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 1989;20:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutierrez J. Specific conditions and stroke. In: Gortta JC, Albers GW, Broderick JP, et al. eds. Stroke: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016:619–631. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skarpathiotakis M, Mandell DM, Swartz RH, Tomlinson G, Mikulis DJ. Intracranial atherosclerotic plaque enhancement in patients with ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tholance Y, Laroche S, Bertrand A, Caudie C. CSF: diagnosis of neurosyphilis in a patient hospitalized for an acute brain stroke [in French]. Ann Biol Clin 2008;66:561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu LL, Zheng WH, Tong ML, et al. Ischemic stroke as a primary symptom of neurosyphilis among HIV-negative emergency patients. J Neurol Sci 2012;317:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landi G, Villani F, Anzalone N. Variable angiographic findings in patients with stroke and neurosyphilis. Stroke 1990;21:333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghanem KG, Moore RD, Rompalo AM, Erbelding EJ, Zenilman JM, Gebo KA. Neurosyphilis in a clinical cohort of HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 2008;22:1145–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sico JJ, Chang CC, So-Armah K, et al. HIV status and the risk of ischemic stroke among men. Neurology 2015;84:1933–1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole JW, Chin JH. HIV infection: a new risk factor for intracerebral hemorrhage? Neurology 2014;83:1690–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johns DR, Tierney M, Felsenstein D. Alteration in the natural history of neurosyphilis by concurrent infection with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1569–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2013. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en_1.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lachaud S, Suissa L, Mahagne MH. Stroke, HIV and meningovascular syphilis: study of three cases [in French]. Rev Neurol 2010;166:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]