Abstract

PURPOSE

We aimed to retrospectively analyze whether background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) on breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) correlates with menarche, menopause, reproductive period, menstrual cycle, gravidity-parity, family history of breast cancer, and the Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category of the patient.

METHODS

The study included 126 pre- and 78 postmenopausal women who underwent breast MRI in our institute between 2011 and 2016. Patients had filled a questionnaire form before the MRI. Two radiologists blinded to patient history graded the BPEs and the results were compared and analyzed.

RESULTS

The BPE was correlated with patient age and the day of menstrual cycle (P < 0.01 for both). No correlation was found with menarche age, menopause age, total number of reproductive years, and family history of breast cancer. In the moderate BPE group, only 1 out of 35 patients and in the marked BPE group only 1 out of 13 patients were postmenopausal and had BI-RADS scores of 4 and 5, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Increased symmetrical BPE is mainly due to current hormonal status in the premenopausal women. High-grade BPE, whether symmetrical or not, is rarely seen in postmenopausal women; hence, these patients should be further investigated or closely followed up.

Background parenchymal enhancement (BPE), which is defined as the enhancement of normal fibroglandular tissue on contrast-enhanced dynamic breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has drawn considerable attention in recent years. This prominence is mostly due to the fact that, similar to the association of breast cancer and breast density on mammography, breast cancer is suggested to be associated with BPE on MRI (1–3). While many studies on this subject are being conducted, BPE has been included in the current version of the Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) lexicon, 2013 (4). It is described as the volume and the intensity of enhancement and is advised to be categorized on the basis of volume but not on the basis of percentages divided into quartiles. This lexicon contains four categories of BPE: minimal, mild, moderate, and marked. The enhancement characteristics may be either patchy or punctate. BPE is a dynamic and variable entity that is affected by many factors, with hormones having the greatest impact. Estrogen, the main hormone to which the female body is exposed from menarche to menopause, causes more prominent BPE by increasing the vascularity and permeability of the breast (5–8). Related to its degree and pattern, BPE may cause false positive and negative results by either overestimating or masking the lesions (9–12). Hence, it is essential to clarify the factors that affect BPE.

In this study, we aimed to assess the relationship between BPE and menarche, gravidity-parity, menopause, total number of reproductive years, phase of menstrual cycle, family history of breast cancer, and the BI-RADS category on MRI.

Methods

Patient population and study design

This retrospective study was performed in the department of radiology of our university hospital. A total of 245 women who underwent breast MRI in our department between 2011 and 2016 were randomly selected from our database. The indications for MRI were mostly based on BI-RADS 3, 4, or 5 lesions on mammography/ultrasonography, dense breasts on mammography, and a family history of breast cancer. Of 245 patients, 41 were excluded and 204 patients (mean age 46.75±9.09 years, age range, 24–71 years) were found eligible for the study. Our exclusion criteria were as follows: prior history of breast operation (breast-conserving surgery or total mastectomy, n=7); prior history of chemotherapy/radiotherapy to the breast or chest wall (n=18); history of hormone use in the last 6 months (n=10); asymmetrical BPE caused by lesions such as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS, n=5); contrast material contraindication (n=1; patient had a single kidney and high creatinine levels).

The study was approved by our local ethics committee. Signed informed consent was obtained from each patient before the MRI. Data about menarche, menopause, pregnancy, and family history of breast cancer was retrieved from the questionnaires that each patient was required to fill before the scan. Their total number of reproductive years was calculated as follows: total number of years from menarche to the scan date for premenopausal patients and from menarche to menopause for postmenopausal patients.

MRI parameters

A 1.5 T MRI scanner (Intera, Philips Medical Systems) with a dedicated double-breast surface coil was used with the patient in the prone position. The standard scanning procedure began with a T2-weighted fat-suppressed spin-echo sequence in the axial plane (TE/TR, 110/7548 ms; inversion delay SPAIR, 80 ms; flip angle, 90°; FOV, 380×380 mm2; acquired voxel size, 1.06×1.74×3.0 mm3; reconstructed voxel size, 0.94×0.94×3.00 mm3; total scanning time, 242 s). T1-weighted fast gradient echo fat-suppressed sequence in axial plane was performed before introducing the contrast agent (TE/TR, 2.4/4.6 ms; flip angle, 10°; FOV, 360×360 mm2; acquired voxel size, 0.9×0.9×2.5 mm3; reconstructed voxel size, 0.83×0.83×2.50 mm3; total scanning time, 60 s). This same sequence was repeated at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 min after the administration of a contrast agent of 0.1 mmol/kg gadolinium diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA).

The unenhanced T1-weighted sequence in the axial plane, delayed (5th minute) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images in the axial plane, and post-contrast subtraction sequences were evaluated. Two radiologists, who were blinded to the complete patient history, independently evaluated the magnetic resonance images in order to check interobserver reliability and reproducibility.

BPE was assessed qualitatively and globally on delayed contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images. It was graded according to the intensity of enhancement and the area it covered in ratio to the total fibroglandular tissue. Compatible with the new BI-RADS lexicon (4) we had 4 groups as follows: minimal enhancement (grade 1), mild enhancement (grade 2), moderate enhancement (grade 3), and marked enhancement (grade 4). The new lexicon does not include no enhancement as a group; hence, we grouped “none” and “minimal” together as a grade. Further, it is already difficult to recognize a minimal enhancing focus between dense fibroglandular tissues and distinguish between no enhancement and minimal enhancement.

Statistical analysis

NCSS (Number Cruncher Statistical System) 2007 software was used for statistical analysis. In addition to descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, median, frequency, minimum, and maximum), the Mann-Whitney U test was used in pairwise comparison of quantitative data not showing normal distribution. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare three or more groups not showing normal distribution, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the group causing the difference. Fisher Freeman Halton test was used for comparison of qualitative data. Cohen’s kappa statistics were used for assessing interobserver reliability. Significance was considered at P < 0.01 and P < 0.05.

Results

The characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Most patients had minimal BPE (44%, n=91) and very few of them had marked BPE (6.3%, n=13).

Table 1.

Distribution of descriptive characteristics

| n=204 | Mean±SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.75±9.09 (24–71) | |

|

| ||

| Menarche age (years) | 12.89±1.23 (10–16) | |

|

| ||

| Menopause age (years) (n=78) | 47.58±5.23 (36–59) | |

|

| ||

| Years since menopause (n=78) | 7.14±7.04 (0–31) | |

|

| ||

| Total number of reproductive years | 31.06±6.67 (12–47) | |

|

| ||

| Days from the first day of last menstruation (days) (n=124) | 10.33±4.46 (1–27) | |

|

| ||

| n (%) | ||

|

| ||

| Menopause | Premenopausal | 126 (61.8) |

| Postmenopausal | 78 (38.2) | |

|

| ||

| Parity | Nulliparous | 34 (16.7) |

| Parous | 170 (83.3) | |

| 1 birth | 58 (34.1) | |

| 2 births | 88 (51.8) | |

| ≥3 births | 24 (14.1) | |

|

| ||

| Family history of breast cancer | 66 (32.4) | |

| First-degree relative | 30 (14.7) | |

| Second-degree relative | 29 (14.2) | |

| Third-degree relative | 7 (3.4) | |

SD, standard deviation.

Between the two readers, an 87.6% agreement was observed for assessing the BPE (κ=0.727, P = 0.04). No disagreement was observed for grade 4 BPE; most of the disagreements were observed between grade 2 and grade 3 BPE.

Assessment of age, menarche age, last day of menstruation, reproductive period length, parity, and menstruation according to BPE grades are summarized in Table 2. A statistically significant difference was found between BPE grade and the age distribution of the patients (P = 0.001). Patients with a minimal BPE were significantly older than patients with mild, moderate, and marked BPE pattern (P = 0.001, P = 0.001, and P = 0.028, respectively).

Table 2.

Assessment of age, menarche age, last day of menstruation, reproductive period length, parity, and menopause according to BPE grades

| BPE grade | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Minimal (n=91) | Mild (n=63) | Moderate (n=37) | Marked (n=13) | |||

| Age (years), median (range) | 6 (27–68) | 44 (24–71) | 43 (26–53) | 45 (32–70) | 0.001a | |

|

| ||||||

| Menarche age (years), median (range) | 13 (10–16) | 13 (11–16) | 13 (10–15) | 13 (11–15) | 0.462a | |

|

| ||||||

| Days since first day of menstruation, median (range) | 10 (6–27) | 10 (7–19) | 9 (1–19) | 5.5 (1–10) | 0.001a | |

|

| ||||||

| Years of reproductive period, median (range) | 32 (13–46) | 30 (12–47) | 30 (13–41) | 33 (18–42) | 0.187a | |

|

| ||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Parity | Nulliparous | 13 (14.3) | 12 (19.0) | 8 (21.6) | 1 (7.7) | 0.616b |

| Parous | 78 (85.7) | 51 (81.0) | 29 (78.4) | 12 (92.3) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Parity | Nulliparous | 13 (14.3) | 12 (19.0) | 8 (21.6) | 1 (7.7) | 0.523b |

| 1 birth | 22 (24.2) | 24 (38.1) | 8 (21.6) | 4 (30.8) | ||

| 2 births | 44 (48.4) | 20 (31.7) | 17 (45.9) | 7 (53.8) | ||

| ≥ 3 births | 12 (13.2) | 7 (11.1) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (7.7) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Menopause | Premenopausal | 35 (38.5) | 43 (68.3) | 36 (97.3) | 12 (92.3) | <0.001b |

| Postmenopausal | 56 (61.5) | 20 (31.7) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (7.7) | ||

BPE, background parenchymal enhancement.

Kruskal Wallis test;

Fisher Freeman Halton test.

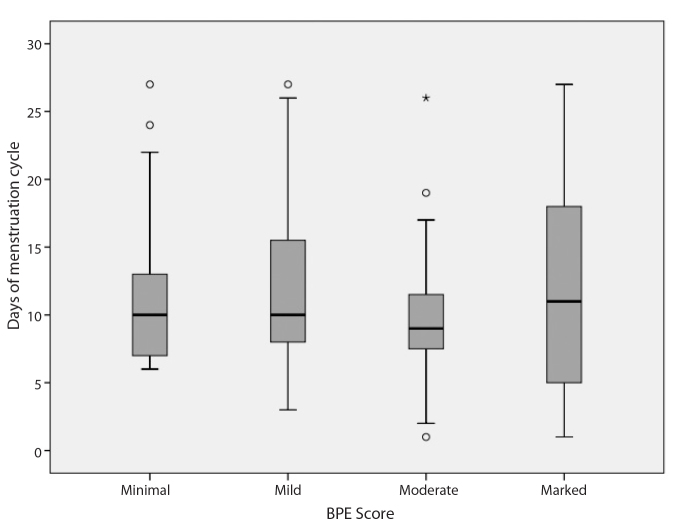

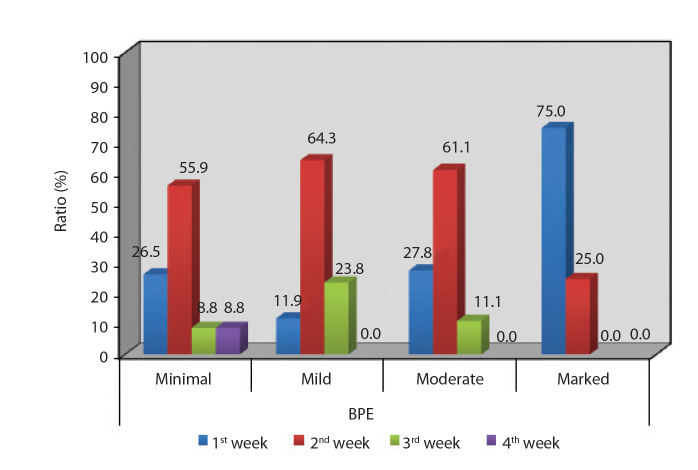

There were 126 premenopausal (61.8%) and 78 postmenopausal (38.2%) patients. For premenopausal patients, mean number of days past since the first day of last menstruation was 10.33±4.46 days (range, 1–27 days) (Table 3, Fig. 1). A statistically significant difference was found between BPE grade and the day of the menstrual cycle when the scanning was performed (P = 0.001). Patients with marked BPE grade were closer to the last day of their menstrual cycle than patients with minimal, mild, and moderate grades (P = 0.001, P = 0.001, and P = 0.006, respectively; Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Assessment of menopause age and menopause length according to BPE grades

| BPE grade | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (n=56) | Mild (n=20) | Moderatea (n=1) | Markeda (n=1) | ||

| Menopause age (years) | 47.5 (36–58) | 48.5 (38–59) | 43 (43–43) | 53 (53–53) | 0.603b |

| Total years in menopause | 5 (0–24) | 4 (0–31) | 10 (10–10) | 17 (17–17) | 0.400b |

Data are presented as median (range).

BPE, background parenchymal enhancement.

Not included in the comparison due to low number of patients.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Figure 1.

Boxplot graphic of the day of menstruation cycle on the scanning day according to BPE grades.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the week of menstruation according to BPE grades (1st week, days 0–7; 2nd week, days 7–14; 3rd week, days 14–21; 4th week, days 21–28).

The menarche age of the patients ranged from 10 to 16 years with a mean of 12.89±1.23 years. No statistically significant difference was found between the BPE grade and the menarche age (P = 0.462).

A statistically significant difference was found when premenopausal and postmenopausal women were compared with respect to the BPE grades. Menopause was significantly more prevalent in patients with minimal BPE grade than in patients with mild, moderate, and marked grades (P = 0.001, P = 0.001, P = 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively).

For postmenopausal patients, the age of menopause ranged from 36 to 59 years with a mean of 47.58±5.23 years and the time since menopause ranged from 0 to 31 years with a mean of 7.14±7.04 years (Table 3). No statistically significant relationship was found between the BPE grade and the menopause age or years since menopause (P = 0.603; P = 0.400, respectively). The total years of the women’s reproductive period ranged from 12 to 47 years with a mean of 30.94±6.77 years. No statistically significant difference was found between the BPE grade and the total number of reproductive years (P = 0.187).

Of the patients, 16.7% (n=34) were nulliparous, while 83.3% (n=170) had at least one full-term pregnancy. Among 170 parous patients, 34.1% (n=58) had 1 child, 51.8% (n=88) had 2 children, and 14.1% (n=24) had 3 or more children. No statistically significant difference was found between the BPE grade and parity of the patients (P = 0.523).

Among 66 patients with a family history of breast cancer, 14.7% (n=30) had a first-degree relative, 14.2% (n=29) had a second-degree relative, and 3.4% (n=7) had a third-degree relative with breast cancer. No statistically significant difference was found between the BPE grades and the family history of breast cancer (P = 0.253).

Agreement between the two readers for assessing the BI-RADS was 90.2% (κ=0.691). No correlation between the BI-RADS score on MRI and BPE was found when all 4 groups were reviewed together (P = 0.664; Table 4). However, in the moderate BPE group, only 1 of 35 patients and in the marked BPE group only 1 of 13 patients were postmenopausal and had BI-RADS scores 4 and 5, respectively, when each group was analyzed. The remaining (n=12) patients of the marked BPE group were premenopausal with BI-RADS scores <5. Furthermore, 70.4% of patients in the minimal BPE group had BI-RADS scores of 1, 2, and 3 compared with 61.5% of the patients in the marked BPE group. In addition, 29.6% of the patients in the minimal BPE group had BI-RADS scores of 4 and 5 compared with 38.5% of the patients in the marked BPE group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Assessment of BI-RADS scores according to BPE grades

| BPE grade | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Minimal (n=91) | Mild (n=63) | Moderate (n=37) | Marked (n=13) | |||

| BI-RADS, median (range) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (1–6) | 2 (1–5) | 0.664a | |

|

| ||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

|

| ||||||

| BI-RADS | Score 1 | 30 (33.0) | 14 (22.2) | 9 (24.3) | 3 (23) | |

| Score 2 | 15 (16.5) | 11 (17.5) | 8 (21.6) | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Score 3 | 19 (20.9) | 16 (25.4) | 9 (24.3) | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Score 4 | 14 (15.4) | 11 (17.5) | 6 (16.2) | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Score 5 | 13 (14.2) | 11 (17.5) | 5 (13.5) | 1 (7.7) | ||

BI-RADS, breast imaging-reporting and data system; BPE, background parenchymal enhancement.

Kruskal Wallis test.

When we defined BI-RADS 1 and 2 as benign cases, BI-RADS 5 as malignant lesions, BPE grade 1 and 2 as BPE-, and BPE grade 3 and 4 as BPE+, the odds of having breast cancer in cases with BPE was calculated as 0.755 (95% CI: 0.200–2.842).

Discussion

BPE is mainly affected by the hormone estrogen. Estrogen affects many systems and organs, including the reproductive system, urinary system, cardiovascular system, bones, skin, hair, and brain. We believe that BPE is the radiologically visible form and reflection of the circulating estrogen in the breast. Alongside estrogen, there are other factors that affect this dynamic enhancement process, such as the amount of contrast material, the patient’s hemodynamic status, parameters of MRI sequences, and vascular anatomy. To keep some of these factors constant, we used the same brand and the same amount of contrast material and the same MRI parameters for all the patients. We tried to exclude patients with factors that could affect BPE. It is known that BPE is much stronger in delayed phases; hence, delayed contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequences were chosen for assessing BPEs (13). Unlike the studies of Giess et al. (11), Telegrafo et al. (14) and Morris et al. (15) BPE was categorized according to the intensity and volume of enhancement but not according to percentages divided into quartiles. This step was compatible with the new BI-RADS lexicon (4). We know that BPE is not always symmetrical and some focal nodular or linear enhancing areas, as observed in DCIS, may accompany. We excluded those BPEs that were obviously asymmetrical.

BPE was found to be influenced mostly by the patients’ age and the day of the menstrual cycle. Both these observations can be explained by the levels of estrogen. Enhancement was highest during weeks 1 and 4 and lowest during week 2. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies (9, 10, 16–18). This is not surprising, because we know that BPE depends on hormonal changes. Estrogen leads to increased contrast uptake of the fibroglandular tissue and BPE by dilating the vessels (19). Similarly, the day of the ovarian cycle certainly affects BPE due to the shift in the levels of estrogen. Müller-Schimpfle et al. (20) evaluated the influences of menstrual cycle timing and patient age on the degree of BPE and reported that BPE was highest between days 21–28 and days 1–6 and lowest between days 7–20; they also reported that BPE was higher in patients aged 35–50 years than in younger and older women. Delille et al. (21) found that the lowest amount of normal tissue enhancement occurred in the first half of the menstrual cycle and recommended that imaging be scheduled for days 3–14 to minimize interpretative difficulties. The European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI) advised to perform the breast MRI in premenopausal women between the 5th and 12th days of the menstrual cycle (the first day of menstruation is referred to as the beginning of the cycle) when the hormonal effects are minimal. In our department, we advise our patients to have contrast-enhanced breast MRI on the second week of the menstrual cycle (days 7–15) to minimize the hormonal effects and thus BPE. Eliminating BPE helps to clearly visualize the contrast-enhancing lesions.

Interestingly, we could not find a correlation with menarche/menopause age, the years since menopause, the length of the reproductive period, and BPE. To our knowledge, there are no studies that have investigated the relationship of BPE with menarche or the total number of reproductive years. The average woman is in reproductive age for most of her life. It is known that early menarche and late menopause are associated with breast cancer due to exposure to estrogen for more years (22–24). We hoped to find a correlation with years since menopause and the total number of reproductive years with BPE (which is linked to estrogen and thus assumed to be linked to breast cancer), but we did not. This could be explained by the rapid change and unstable nature of BPE.

We also did not find a correlation between parity and BPE. This could be explained by the fact that hormonal changes during pregnancy are temporary and estrogen levels return to the normal level during the postpartum period. This can only be clarified by including pregnant patients in a study group and assessing their BPEs. There are only a few studies with limited sample size involving pregnant patients (25).

BPE is thought to be correlated with breast cancer (9, 10). This is not surprising, because we know that estrogen is associated with breast cancer (22–24). When each BPE group was evaluated individually, it was found that only 1 patient from the moderate BPE group and only 1 patient from the marked BPE group were postmenopausal. These 2 patients had BI-RADS scores of 4 and 5, respectively, and one patient’s mother had breast cancer. We calculated the odds of having breast cancer in high-grade BPE as 0.755. This ratio was higher than those reported by King et al. (9) and Dontchos et al. (10) and close to that reported by Telegrafo et al. (14), which was calculated as 0.80 by Bennani-Baiti et al. (26) in a letter to the editor in reply to the article by Telegrafo.

These findings justify concerns about the possible link between high-grade BPE and breast cancer and are contrary to Bennani-Baiti et al. (16), who claimed that BPE is not associated with breast cancer odds and that BPE’s decrease with age is an indicator of only age. In their study, they claimed that the differences from the results of King et al. (9) and Dontchos et al. (10) were due to a high-risk study population in the former groups. Bennani-Baiti claims that in the non-high-risk group, BPE is not associated with malignancy; however, our study group also excluded patients with high risks such as previous history of breast cancer, breast surgery, and/or radiotherapy on the chest area.

Telegrafo et al. (14) evaluated postmenopausal and premenopausal patients in 2015. They found a significant difference in the distribution of the BPE types in benign lesions compared with malignant ones; we had a similar finding such that 29.6% of the patients in the minimal BPE group had BI-RADS scores of 4 and 5 compared with 38.5% of the patients in the marked BPE group.

No disagreement was observed between observers for high-grade BPE cases; this implies that the present method is a reliable method for assessing marked enhancement patterns that are thought be associated with cancer. In our clinic, postmenopausal patients with high-grade BPE are managed with care and are followed-up at shorter intervals even if they are lesion-free.

Unfortunately, this study has some limitations. The most important one is our subjective-qualitative method. Some studies have used software for quantitative assessment of BPE (27). However, we believe that these methods are not yet suitable for routine reporting. Future research with larger study groups may enable quantitative BPE measurement by using more practical computer programs and more objective and reproducible results. MRI indications such as family history of breast cancer and suspicious lesions on mammography and sonography might cause a selection bias in favor of patients with BI-RADS 4 and 5 lesions. Moreover, there were some disagreements between readers for grade 2 and 3 cases of BPE. This might be a drawback of the new BI-RADS lexicon and lower its reliability. Another limitation was the relatively low number of grade 4 BPE cases. A statistically significant correlation with a family history of breast cancer and high-grade BPE could have been found if we had more BPE cases, and more reliable results could have been obtained with more patients, particularly those with grade 4 BPE.

In conclusion, as BPE has been included in the new BI-RADS lexicon, we should familiarize ourselves with it and understand its scope clearly. We know that BPE is affected by many factors, mainly estrogen. BPE grade is clearly correlated with the age of the patient and the day of the menstrual cycle. Moderate or marked BPE could be normally seen in women of reproductive age if they are imaged in the first or last week of their menstrual cycle. We believe it is unnecessary to further investigate women of reproductive age who are in the first or last week of their menstrual cycle with moderate or marked BPE on MRI. However, marked-moderate enhancement might be a sign of malignancy for postmenopausal women and we advise caution and follow-up for these patients.

Main points.

Background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) on breast MRI is linked to estrogen levels and varies among women.

BPE is a dynamic process and can change over time, diminishing by women age.

Postmenopausal women, even without any lesions on the breast, should be followed up closely if they have high-grade BPE.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Saftlas AF, Hoover RN, Brinton LA, et al. Mammographic densities and risk of breast cancer. Cancer. 1991;67:2833–2838. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910601)67:11<2833::aid-cncr2820671121>3.0.co;2-u. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19910601)67:11<2833::AID-CNCR2820671121>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast densityand parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1159–1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Kerlikowske K. Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Mammographic density and breast cancer risk: current understanding and future prospects. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:337–347. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00004. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris EA, Comstock CE, Lee CH, et al. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013. ACR BI-RADS® Magnetic Resonance Imaging. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishman J, Osborne MP, Telang NT. The role of estrogen in mammary carcinogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;768:91–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb12113.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb12113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas C, Gustafsson JÅ. The different roles of ER subtypes in cancer biology and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:597–608. doi: 10.1038/nrc3093. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo J, Russo IH. The role of estrogen in the initiation of breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;102:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd MC, Alfarouk KO, Verduzco D, et al. Vascular measurements correlate with estrogen receptor status. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:279. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-279. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dontchos BN, Rahbar H, Partridge SC, et al. Are qualitative assessments of background parenchymal enhancement, amount of fibroglandular tissue on MR Images, and mammographic density associated with breast cancer risk? Radiology. 2015;276:371–380. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142304. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2015142304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King V, Brooks JD, Bernstein JL, Reiner AS, Pike MC, Morris EA. Background parenchymal enhancement at breast MR imaging and breast cancer risk. Radiology. 2011;260:50–60. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11102156. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11102156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giess CS, Yeh ED, Raza S, Birdwell RL. Background parenchymal enhancement at breast MR imaging: normal patterns, diagnostic challenges, and potential for false-positive and false-negative interpretation. Radiographics. 2014;34:234–247. doi: 10.1148/rg.341135034. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11102156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatelia K, Singh K, Singh R. TLRs: linking inflammation and breast cancer. Cell Signal. 2014;26:2350–2357. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.07.035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kajihara M, Goto M, Hirayama Y, et al. Effect of the menstrual cycle on background parenchymal enhancement in breast MR imaging. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2013;12:39–45. doi: 10.2463/mrms.2012-0022. https://doi.org/10.2463/mrms.2012-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Telegrafo M, Rella L, Stabile Ianora AA, Angelelli G, Moschetta M. Breast MRI background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) correlates with the risk of breast cancer. Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;34:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2015.10.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris EA. Diagnostic breast MR imaging: current status and future directions. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45:863–880. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2007.07.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennani-Baiti B, Dietzel M, Baltzer PA. MRI background parenchymal enhancement is not associated with breast cancer. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0162936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158573. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baltzer PA, Dietzel M, Vag T, et al. Clinical MR mammography: impact of hormonal status on background enhancement and diagnostic accuracy. Rofo. 2011;183:441–447. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246072. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1246072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cubuk R, Tasali N, Narin B, Keskiner F, Celik L, Guney S. Correlation between breast density in mammography and background enhancement in MR mammography. Radiol Med. 2010;115:434–441. doi: 10.1007/s11547-010-0513-4. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1246072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhl CK, Bieling HB, Gieseke J, et al. Healthy premenopausal breast parenchyma in dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging of the breast: normal contrast medium enhancement and cyclical-phase dependency. Radiology. 1997;203:137–144. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122382. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller-Schimpfle M, Ohmenhaüser K, Stoll P, Dietz K, Claussen CD. Menstrual cycle and age: influence on parenchymal contrast medium enhancement in MR imaging of the breast. Radiology. 1997;203:145–149. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122383. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delille JP, Slanetz PJ, Yeh ED, Kopans DB, Halpern EF, Garrido L. Hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women: breast tissue perfusion determined with MR imaging—initial observations. Radiology. 2005;235:36–41. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2351040012. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2351040012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1141–1151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70425-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70425-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endogenous Hormones and Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. Circulating sex hormones and breast cancer risk factors in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of 13 studies. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:709–722. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.254. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willett WC, Tamimi R, Hankinson SE, Hazra A, Eliassen AH, Colditz GA. Chapter 18: Nongenetic factors in the causation of breast cancer. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK, editors. Diseases of the breast. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espinosa LA, Daniel BL, Vidarsson L, Zakhour M, Ikeda DM, Herfkens RJ. The lactating breast: contrast-enhanced MR imaging of normal tissue and cancer. Radiology. 2005;237:429–436. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372040837. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2372040837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennani-Baiti B, Baltzer PA. Reply to “Breast MRI background parenchymal enhancement (BPE) correlates with the risk of breast cancer”. Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;34:1337–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2016.07.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu S, Weinstein SP, DeLeo MJ, 3rd, et al. Quantitative assessment of background parenchymal enhancement in breast magnetic resonance images predicts the risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:67. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0577-0. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0577-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]