Abstract

Background/Aims

Because of the poor prognosis of diffuse-type gastric cancer, early detection is important. We investigated the clinical characteristics and prognosis of diffuse-type early gastric cancer (EGC) diagnosed in subjects during health check-ups.

Methods

Among 121,111 subjects who underwent gastroscopy during a routine health check-up, we identified 282 patients with 286 EGC lesions and reviewed their clinical and tumor-specific parameters.

Results

Patients with diffuse-type EGC were younger, and 48.1% of them were female. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG (Hp-IgG) was positive in 90.7% of diffuse-type EGC patients (vs 75.9% of intestinal-type EGC, p=0.002), and the proportion of diffuse-type EGC cases increased significantly with increasing Hp-IgG serum titers (p<0.001). Diffuse-type EGC had pale discolorations on the tumor surface (26.4% vs 4.0% in intestinal-type EGC, p<0.001) and were often located in the middle third of the stomach. Submucosal invasion or regional nodal metastasis was observed more commonly in patients with diffuse-type EGC. However, during the median follow-up period of 50 months, 5-year disease-free survival rates did not differ between the groups.

Conclusions

Diffuse-type EGC shows different clinical and endoscopic characteristics. Diffuse-type EGC is more closely associated with Hp-IgG seropositivity and a higher serum titer. Early detection results in excellent prognosis.

Keywords: Stomach neoplasms, Diffuse-type, Early diagnosis, Prognosis, Endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is the most prevalent malignancy in Korea.1 A nationwide health check-up program by the Korean Central Cancer Registry recommends biennial gastroscopy for individuals older than 40 years.2,3 The prognosis of GC is improving because of early diagnosis of the condition with the screening program.

Histologically, GC is classified into intestinal and diffuse types.4 Intestinal-type GC arises mostly from Helicobacter pylori-induced chronic gastritis through the intermediate stages of atrophic and metaplastic gastritis.5 On the contrary, active inflammation of the gastric mucosa by H. pylori induces diffuse-type GC without passing through the premalignant lesions.6,7 The obscure premalignant changes and active inflammation of the mucosa may lead to early-stage diffuse-type GC being missed during endoscopic examination.

Diffuse-type GC has a worse prognosis than intestinal-type GC because of the frequent nodal and distant metastasis in the former.8–10 Thus, understanding the characteristics of diffuse-type GC at an early stage is essential to improve the detection and prognosis of the disease. In this study, we evaluated the clinical and endoscopic features of the patients with diffuse-type early gastric cancer (EGC) diagnosed in subjects undergoing health check-up, and compared the prognosis of these subjects to that of patients with intestinal-type EGC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients and data collection

From a database of 121,111 subjects who underwent gastroscopy during health check-up between January 2008 and December 2013 at the Health Screening and Promotion Center of Asan Medical Center, we identified 358 patients who were diagnosed with gastric malignancies. Of these, 76 patients were excluded from the analysis owing to advanced-stage GC (n=48), cardia cancer (n=14), stump cancer (n=10), and lymphoma (n=4). Finally, 282 patients with non-cardia EGC were included in this study. All participants were voluntary, self-referred asymptomatic adults who completed a self-administered questionnaire that detailed their personal medical history, family history of GC, and lifestyle habits. Our screening protocol for GC is based on the Korean National Gastric Cancer Screening Program,2 in which asymptomatic individuals older than 40 years of age who have an average risk for GC are recommended to undergo biennial gastroscopy.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center (2014-0455), which confirmed that it accorded with the Ethical Guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2. Endoscopic procedures

Gastroscopy was performed by specialized gastrointestinal endoscopists, who had received gastrointestinal fellowship training and board certification. A high-resolution electronic endoscope (GIF-Q260 or GIF-H260; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) was used for gastroscopy. Patients were sedated with intravenous midazolam (0.05 mg/kg), and their cardiorespiratory functions were monitored closely during the procedure. Endoscopic features such as lesion size, location, and macroscopic types were recorded for any suspicious lesions. Presence of abnormal fold convergence, spontaneous bleeding at foci, mucosal defect (erosion or ulceration), and color change on the surface of lesions was noted. The macroscopic features of the tumors were classified into three major types: elevated (I and IIa), flat (IIb), or depressed (IIc and III).11,12 The extension of mucosal atrophy was categorized as closed or open type, according to Kimura and Takemoto classification.13

3. Histological classification

Tumors were classified as diffuse or intestinal type on the basis of the Lauren criteria.4 Any tumor showing more than two histologic types was classified into one type according to the predominant histologic pattern. According to glandular differentiation, tumors were categorized into differentiated or undifferentiated type, based on the World Health Organization criteria.14 EGC is defined as GC confined to the mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of regional lymph node metastasis.11 Endoscopic resection was performed in cases where the differentiated-type EGC was confined to the mucosa, was <20 mm in diameter, and did not show nodal enlargement on abdominal computed tomography.15,16

4. Serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody

Serological positivity to anti-H. pylori IgG (Hp-IgG) was determined using the H. pylori IgG immunoassay system (Immulite 2000; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products Ltd., Llanberis, Gwynedd, UK). The calibration range of this immunoassay is 0.4 to 8.0 U/mL, and the serum Hp-IgG titer is reported as follows: negative, 0 to 0.8 U/mL; equivocal, 0.9 to 1.0 U/mL; positive, 1.1 to 7.9 U/mL; and high-positive, values higher than the upper calibration limit. In this study, patients with Hp-IgG values ≤1.0 U/mL were considered seronegative for H. pylori infection because most of those with equivocal level of Hp-IgG titer had no evidence of current H. pylori infection.17 We divided patients in the positive group into two subgroups, the low-positive (1.1 to 3.6 U/mL) and the mid-positive (3.7 to 7.9 U/mL) groups, in which the cutoff value was determined to ensure that the same number of patients were included in each subgroup.

5. Statistical analysis

The baseline continuous and categorical variables are presented as the mean±standard deviation and number with percentage, respectively. Group comparisons of the continuous variables were performed using Student t-test, and the categorical variables were compared using the Pearson chi-square test. The correlations between the Hp-IgG titer distribution and proportion of diffuse-type EGC were analyzed using linear-by-linear association. The 5-year disease-free survival rate was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. A p-values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

1. Clinical characteristics of patients with intestinal- and diffuse-type EGC

Among the 282 patients with EGC, intestinal-type EGC was diagnosed in 176 lesions in 174 patients (61.7%) and diffuse-type EGC was diagnosed in 110 lesions in 108 patients (38.3%). Patients with diffuse-type EGC were younger than those with intestinal-type EGC, and 48.1% of them were female (Table 1). All six patients with EGC who were aged less than 40 years were diagnosed with diffuse-type EGC. More patients with intestinal-type EGC reported histories of smoking and the presence of GC in first-degree relatives.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Early Gastric Cancer

| Total (n=282) | Intestinal-type (n=174) | Diffuse-type (n=108) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 56.8±9.8 | 59.1±9.2 | 53.1±9.6 | <0.001 |

| <40 | 6 (2.1) | 0 | 6 (5.6) | |

| 40–59 | 174 (61.7) | 99 (56.9) | 75 (69.4) | |

| ≥60 | 102 (36.2) | 75 (43.1) | 27 (25.0) | |

| Female sex | 84 (29.8) | 32 (18.4) | 52 (48.1) | <0.001 |

| Family history of gastric cancer* | 59 (20.9) | 46 (26.4) | 13 (12.0) | 0.004 |

| Alcohol consumption | 114 (40.4) | 74 (42.5) | 40 (37.1) | 0.463 |

| Smoker | 170 (60.3) | 121 (69.6) | 49 (45.4) | <0.001 |

| Anti-H. pylori IgG positivity | 230 (81.6) | 132 (75.9) | 98 (90.7) | 0.002 |

| Serum anti-H. pylori IgG titer, U/mL | <0.001 | |||

| Negative (0–1.0)† | 52 (18.4) | 42 (24.1) | 10 (9.2) | |

| Low-positive (1.1–3.6) | 98 (34.8) | 63 (36.2) | 35 (32.4) | |

| Mid-positive (3.7–7.9) | 92 (32.6) | 55 (31.6) | 37 (34.3) | |

| High-positive (≥8.0) | 40 (14.2) | 14 (8.1) | 26 (24.1) | |

| First screening endoscopy | 84 (29.8) | 52 (29.9) | 32 (29.6) | 0.964 |

| Screening interval, mo | 23.8±20.5 | 25.9±23.2 | 20.4±15.1 | 0.066 |

| Treatment | <0.001 | |||

| Endoscopic resection | 135 (47.9) | 127 (73.0) | 8 (7.4) | |

| Surgical resection | 147 (52.1) | 47 (27.0) | 100 (92.6) |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

First-degree relatives;

Including 11 cases with equivocal serum anti-H. pylori IgG titers.

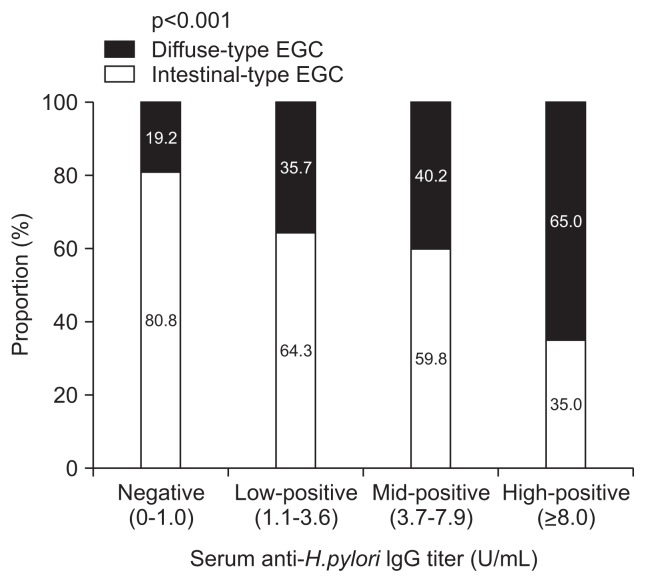

Serum Hp-IgG was found to be positive in 90.7% of patients with diffuse-type EGC (vs 75.9% of patients with intestinal-type EGC; p=0.002). A high-positive titer of serum Hp-IgG (≥8.0 U/mL) was reported in 24.1% of patients with diffuse-type EGC and 8.1% of patients with intestinal-type EGC. The proportion of diffuse-type EGC increased significantly with an increasing Hp-IgG serum titer (p<0.001) (Fig. 1); 65.0% of the patients with a high-positive Hp-IgG titer were diagnosed with diffuse-type EGC.

Fig. 1.

The proportions of diffuse-type early gastric cancer (EGC) according to serum anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG titers. The proportion of diffuse-type EGC cases increased significantly with serum anti-H. pylori IgG titers (p-value by linear-by-linear association).

There were no differences in the proportions of patients who underwent their first-time screening gastroscopy and in the time interval from the latest gastroscopy. Endoscopic resection was performed in 73.0% of patients with intestinal-type EGC, whereas surgical resection was performed in 92.6% of patients with diffuse-type EGC.

2. Comparison of endoscopic features

Diffuse-type EGC mostly consisted of flat or depressed lesions (90.0%) with an ill-defined border (81.8%). Intestinal-type EGC was often found in the lower third of the stomach (72.2%), whereas in 56.4% of the patients, diffuse-type EGC was located in the middle third of the stomach. The proportion of tumors with pale discoloration on the surface was significantly different between patients with diffuse-type and intestinal-type EGC (26.4% and 4.0%, respectively; p<0.001). Open-type atrophic gastritis in the surrounding mucosa was observed in 69.5% of patients with intestinal-type EGC (vs 51.9% of patients with diffuse-type EGC; p=0.003). Table 2 compares the endoscopic features of intestinal- and diffuse-type EGCs.

Table 2.

Endoscopic Features of Intestinal- and Diffuse-Type Early Gastric Cancer

| Intestinal-type (n=176) | Diffuse-type (n=110) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size, mm | 14.4±11.6 | 20.8±15.6 | <0.001 |

| Tumor location | <0.001 | ||

| Lower third | 127 (72.2) | 38 (34.5) | |

| Middle third | 40 (22.7) | 62 (56.4) | |

| Upper third | 9 (5.1) | 10 (9.1) | |

| Macroscopic feature | <0.001 | ||

| Elevated | 64 (36.4) | 11 (10.0) | |

| Flat | 44 (25.0) | 53 (48.2) | |

| Depressed | 68 (38.6) | 46 (41.8) | |

| Tumor border, ill-defined | 73 (41.5) | 90 (81.8) | <0.001 |

| Pale discoloration on tumor surface | 7 (4.0) | 29 (26.4) | <0.001 |

| Converging folds | 9 (5.1) | 17 (15.5) | 0.003 |

| Spontaneous tumor bleeding | 39 (22.2) | 26 (23.6) | 0.772 |

| Mucosal defect | 76 (43.2) | 39 (35.5) | 0.195 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

3. Pathologic features and prognosis

The mean tumor size was 17.7±14.9 mm in intestinal-type EGC and 25.3±16.4 mm in diffuse-type EGC (p<0.001). Submucosal invasion or regional nodal metastasis was more common in diffuse-type EGC (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pathologic Features of Intestinal- and Diffuse-Type Early Gastric Cancer

| Intestinal-type (n=176) | Diffuse-type (n=110) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size, mm | 17.7±14.9 | 25.3±16.4 | <0.001 |

| Glandular differentiation | <0.001 | ||

| Differentiated | 166 (94.3) | 7 (6.4) | |

| Undifferentiated | 10 (5.7) | 103 (93.6) | |

| Depth of invasion | 0.002 | ||

| Mucosa | 157 (89.2) | 83 (71.8) | |

| Submucosa | 19 (10.8) | 27 (24.5) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 9 (5.1) | 8 (7.3) | 0.452 |

| Metastatic regional lymph node | 2 (1.1) | 8 (7.3) | 0.006 |

| Perineural invasion | 1 (0.6) | 5 (4.5) | 0.022 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

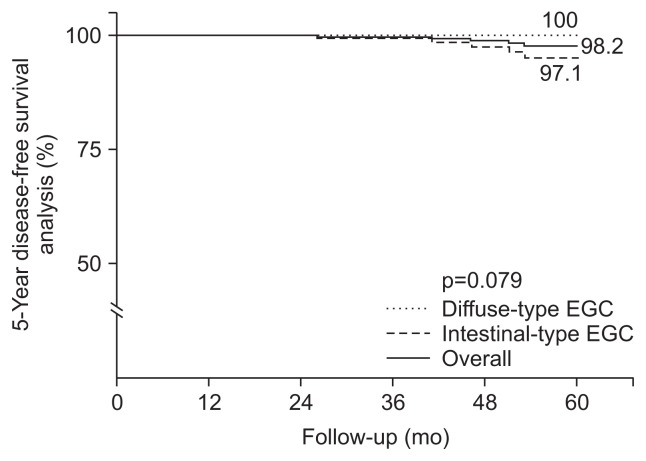

No patients died during the median follow-up period of 50 months (range, 15 to 91 months). Five cases of tumor recurrence were reported after curative resection: Four cases of metachronous recurrence and one case of regional metastasis after surgery in patients with intestinal-type EGC. The overall 5-year disease-free survival rate was 98.2% (Fig. 2). The 5-year disease-free survival rates did not differ between patients with intestinal-type EGC and diffuse-type EGC (97.1% and 100%, respectively; p=0.079).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for the 5-year disease-free survival analysis. The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 98.2% in all patients with early gastric cancer (EGC), 97.1% in patients with intestinal-type EGC, and 100% in patients with diffuse-type EGC (p=0.079).

DISCUSSION

The current study showed that patients with diffuse-type EGC diagnosed during health check-ups were closely associated with younger age, female sex, and Hp-IgG seropositivity. In addition, diffuse-type EGC was found more often in those with a higher serum Hp-IgG titer. When diagnosed at an early stage, the prognosis of diffuse-type EGC is excellent.

Diffuse-type EGC was observed more often in younger and female patients. In addition, 90.7% of patients with diffuse-type EGC showed positive serum Hp-IgG test results. The relatively lower positive rate of serum Hp-IgG (75.9%) in patients with intestinal-type EGC can be explained by the disappearance of H. pylori from the atrophic and metaplastic gastric mucosa with the progression of H. pylori infection.18 In a study that reported the characteristics of GC according to H. pylori infection status, GC patients with past H. pylori infection were older and predominantly male, compared with the patients with current infection.19 In terms of Lauren’s histological classification, the proportion of diffuse-type GC was much higher in patients with GC who were currently infected with H. pylori than in those infected in the past. Moreover, patients with a serologic evidence of past infection had a higher proportion of diffuse-type GC compared with patients with a histologic past-infection (38.2% vs 19.8%, respectively). In that study, H. pylori test was positive in 87.2% of patients with GC, and seronegative past infection was reported in 10.5% of the patients.

In addition to the close association between diffuse-type EGC and Hp-IgG seropositivity, the proportion of diffuse-type EGC increased significantly with an increasing serum Hp-IgG titer. A previous study reported that a higher Hp-IgG titer was associated with a risk of diffuse-type GC.20 In an analysis of patients with H. pylori-infected non-atrophic gastritis, the incidence of GC was significantly higher in a group of patients with a high Hp-IgG titer, and 80% of the cancers that developed in the high-titer group demonstrated diffuse-type histology.7,21 In another study, the risk of diffuse-type GC was the highest in patients with high Hp-IgG titer without mucosal atrophy.22 Considering that serum Hp-IgG titer was positively associated with the severity of histological inflammation,23,24 some investigators speculated that the high inflammatory response to H. pylori infection increases the risk of developing diffuse-type GC in the absence of premalignant lesions.25 They suggested careful follow-up with endoscopy at regular intervals in such subjects with a high-positive Hp-IgG titer.

On endoscopy, 26.4% of the cases of diffuse-type EGC showed pale discoloration on tumor surface. Diffuse-type tumors tend to infiltrate laterally without exposure to the mucosal surface and have a reduced subepithelial capillary network.26–28 Pale discoloration on the tumor surface may be used as an endoscopic predictor for diffuse-type GC prior to resection.29 Additionally, 65.5% of the tumors in diffuse-type EGC were located in the corpus part of the stomach (vs 27.8% in intestinal-type GC). Previous study showed that lesions located in the corpus could be missed easily and 70% of interval GC was undifferentiated-type histology.30 Therefore, endoscopic examination should be performed carefully in this region, because early detection of tumors could be hampered by the gastric folds and oblique endoscopic view.

Diffuse-type GCs show an aggressive biological behavior and poor prognosis. In a previous report, patients with signet ring cell carcinoma and poorly differentiated GC in advanced stages demonstrated significantly lower 10-year overall survival rates than the survival rates of patients with advanced differentiated GC.31 However, the 10-year overall survivals were better in patients with early signet ring cell and poorly differentiated carcinomas than in those with differentiated carcinomas (95%, 89%, and 84%, respectively). The 10-year overall survival of patients with mucosa-confined EGC was 93.4% for patients with intestinal-type EGC and 90.7% for those with diffuse-type GC.32 The 10-year recurrence-free survival rate of patients with intestinal-type and diffuse-type EGC was 91.4% and 92.9%, respectively. In our study, 71.8% of diffuse-type EGCs were mucosa-confined cancers. The 5-year disease-free survival of patients with diffuse-type EGC was comparable to that of patients with intestinal-type EGC. The excellent prognosis of our patients may also be attributed to the endoscopic screening at regular intervals. During our study period, 88.2% of patients with GC were diagnosed as having EGC, and interval endoscopy was performed in 70.2% of the patients with EGC. The mean screening interval was 25.9 months in patients with intestinal-type EGC and 20.4 months in patients with diffuse-type EGC. As previously reported, endoscopic screening was associated with a significant increase in the detection of EGC and improvement in the chance of 5-year survival.33,34

In conclusion, diffuse-type EGC diagnosed in subjects during health check-ups was more closely associated with H. pylori seropositivity and found more often in those with a high-positive Hp-IgG serum titer. This type of tumor may present with pale discoloration in the middle third of the stomach in the absence of surrounding mucosal atrophy. The clinical and endoscopic characteristics of diffuse-type EGC may help in the early detection of the tumors, consequently leading to a good prognosis.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee HJ, Yang HK, Ahn YO. Gastric cancer in Korea. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:177–182. doi: 10.1007/s101200200031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National cancer control programs in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22( Suppl):S3–S4. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.S.S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi IJ. Endoscopic gastric cancer screening and surveillance in high-risk groups. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:497–503. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.6.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma: an attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process: first American Cancer Society award lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nardone G, Rocco A, Malfertheiner P. Review article: Helicobacter pylori and molecular events in precancerous gastric lesions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:261–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe M, Kato J, Inoue I, et al. Development of gastric cancer in nonatrophic stomach with highly active inflammation identified by serum levels of pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody together with endoscopic rugal hyperplastic gastritis. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2632–2642. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribeiro MM, Sarmento JA, Sobrinho Simões MA, Bastos J. Prognostic significance of Lauren and Ming classifications and other pathologic parameters in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;47:780–784. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810215)47:4<780::AID-CNCR2820470424>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adachi Y, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Sato K, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma: well versus poorly differentiated type. Cancer. 2000;89:1418–1424. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1418::AID-CNCR2>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee T, Tanaka H, Ohira M, et al. Clinical impact of the extent of lymph node micrometastasis in undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Oncology. 2014;86:244–252. doi: 10.1159/000358803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/PL00011681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Participants in the Paris Workshop. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(6 Suppl):S3–S43. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(03)02159-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;1:87–97. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1098086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. World Health Organization classification of tumors. Lyon: IARC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T, Yeh R, Gotoda T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4490–4498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.19.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotoda T. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Na HK, Cho CJ, Bae SE, et al. Atrophic and metaplastic progression in the background mucosa of patients with gastric adenoma. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang HY, Kim N, Park YS, et al. Progression of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia drives Helicobacter pylori out of the gastric mucosa. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2310–2315. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwak HW, Choi IJ, Cho SJ, et al. Characteristics of gastric cancer according to Helicobacter pylori infection status. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1671–1677. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatemichi M, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Tsugane S Japan Public Health Center Study Group. Different etiological role of Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection in carcinogenesis between differentiated and undifferentiated gastric cancers: a nested case-control study using IgG titer against Hp surface antigen. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:360–365. doi: 10.1080/02841860701843035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida T, Kato J, Inoue I, et al. Cancer development based on chronic active gastritis and resulting gastric atrophy as assessed by serum levels of pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody titer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1445–1457. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tatemichi M, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Tsugane S JPHC Study Group. Clinical significance of IgG antibody titer against Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2009;14:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreuning J, Lindeman J, Biemond I, Lamers CB. Relation between IgG and IgA antibody titres against Helicobacter pylori in serum and severity of gastritis in asymptomatic subjects. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:227–231. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu PI, Lai KH, Tseng HH, et al. Correlation of serum immunoglobulin G Helicobacter pylori antibody titers with histologic and endoscopic findings in patients with dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:587–591. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199712000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kishikawa H, Kimura K, Takarabe S, Kaida S, Nishida J. Helicobacter pylori antibody titer and gastric cancer screening. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:156719. doi: 10.1155/2015/156719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ninomiya Y, Yanagisawa A, Kato Y, Tomimatsu H. Unrecognizable intramucosal spread of diffuse-type mucosal gastric carcinomas of less than 20 mm in size. Endoscopy. 2000;32:604–608. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-16506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawada S, Fujisaki J, Yamamoto N, et al. Expansion of indications for endoscopic treatment of undifferentiated mucosal gastric cancer: analysis of intramucosal spread in resected specimens. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1376–1380. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0883-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adachi Y, Mori M, Enjoji M, Sugimachi K. Microvascular architecture of early gastric carcinoma: microvascular-histopathologic correlates. Cancer. 1993;72:32–36. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930701)72:1<32::AID-CNCR2820720108>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi JM, Kim SG, Yang HJ, et al. Endoscopic predictors for undifferentiated histology in differentiated gastric neoplasms prior to endoscopic resection. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park MS, Yoon JY, Chung HS, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of interval gastric cancer in Korea. Gut Liver. 2015;9:166–173. doi: 10.5009/gnl13425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chon HJ, Hyung WJ, Kim C, et al. Differential prognostic implications of gastric signet ring cell carcinoma: stage adjusted analysis from a single high-volume center in Asia. Ann Surg. 2017;265:946–953. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pyo JH, Ahn S, Lee H, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of mixed-type T1a gastric cancer based on Lauren’s classification. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(Suppl 5):784–791. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5549-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khanderia E, Markar SR, Acharya A, Kim Y, Kim YW, Hanna GB. The influence of gastric cancer screening on the stage at diagnosis and survival: a meta-analysis of comparative studies in the far east. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:190–197. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gong EJ, Ahn JY, Jung HY, et al. Risk factors and clinical outcomes of gastric cancer identified by screening endoscopy: a case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:301–309. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]