Abstract

Since the 1990s it has been known that B- and T- lymphocytes exhibit low-level, constitutive signaling in the basal state (“tonic signaling”). These lymphocytes display a range of affinity for self, which generates a scale of tonic signaling. Surprisingly, what signaling pathways are active in the basal state and the functional relevance of the observed tonic signaling heterogeneity remain open questions today. Here we summarize what is known about the mechanistic and functional details of tonic signaling. We highlight recent advances that have increased our understanding of how the amount of tonic signal impacts immune function, describing novel tools that have moved the field forward and towards molecular understanding of tonic signaling.

Keywords: tonic signaling, B lymphocyte, T lymphocyte

Tonic Signals in Lymphocytes

Engagement of the B cell receptor (BCR – see Glossary) or T cell receptor (TCR) by their cognate antigens triggers robust activation of signaling pathways in lymphocytes, pathways that have been well characterized over the years (reviewed in [1–3]). However, it has also been appreciated for many years that even in the absence of robust and activating antigen triggers, low-level phosphorylation of signaling intermediates can be observed in resting lymphocytes. These low-level “basal” or “tonic” signals are thought to be driven by the surface expression of the BCR in B lymphocytes, and by transient interactions between the TCR on peripheral T lymphocytes with self peptide-MHC (pMHC) in lymphoid organs. Tonic signals have been observed in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, but are perhaps best understood in B lymphocytes where they play an essential role in B cell survival [4–9]. Although the function of tonic signals in T cells has not been clearly defined, recent studies have implicated tonic signaling pathways in a number of T cell effector functions. It has been postulated that tonic signals are generated as a result of a dynamic equilibrium between positive and negative regulators of antigen receptor signaling [10,11]. The identity and spatio-temporal localization of signaling intermediates that mediate tonic signaling remain incompletely defined. In this review, we outline historical studies of tonic signaling pathways in lymphocytes, we discuss recently developed tools that have aided studies of these pathways, and we particularly focus on recent studies revealing their survival-independent functions in CD4+ T cells.

Tonic BCR signaling is essential for B cell survival

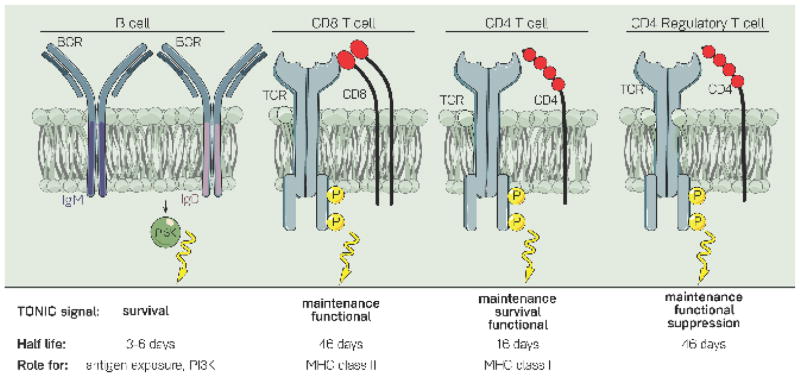

In B cells, tonic BCR signals are crucial for cell survival; indeed, the inducible deletion of BCR expression leads to mature B cell loss with a measured half-life of 3–6 days [6]. Low-level, constitutive PI3K signaling was shown to be sufficient to rescue the survival of mature B cells in which the BCR had been conditionally deleted (BCRneg cells) [7] (Figure 1). On the other hand, constitutive canonical NF-kB signals, MEK activity, or Bcl2 overexpression alone are not sufficient to sustain the survival of BCRneg B cells [6]. Together these data imply that the PI3K signaling pathway is necessary and sufficient for tonic BCR signal-mediated survival.

Figure 1. Receptor-ablation studies provide insights into the role of tonic signals in B- and T- lymphocytes.

When the BCR is ablated from B cells, they rapidly die within 3–6 days. Additional experiments uncovered a role for IgD-PI3K signaling and a potential role for antigen exposure in this tonic survival signal. Ablation of the TCR from CD8+, CD4+, or CD4+ regulatory T cells revealed a maintenance and functional role, and not a survival role, for the TCR in tonic signaling. Of note, while TCR ablation affects the functional capacities of regulatory T cells, it does not have an effect on Foxp3 expression. The half-life of receptor-negative cells, as well as what is known about the mechanism of this tonic signal, are outlined below each cell type. Receptor-positive CD8+ T cells have a half-life of 162 days, and receptor-positive CD4+ cells have a half-life of 78 days.

Prior studies have not resolved whether endogenous antigen exposure plays a role in tonic signaling and B cell survival [12–14]. Our recent work has shown that resting naïve follicular B cells exhibit a range of endogenous antigen recognition [15]. Studies of B cells expressing BCRs that lack antigen-binding domains - but presumably retain antigen-independent tonic signals - suggest that “sub-threshold” endogenous antigen recognition in vivo may confer a survival advantage in competition with other clones [16].

Naïve mature follicular B cells uniquely express two different BCR isotypes, IgM and IgD, which are splice isoforms generated from the same primary transcript [17,18]. Since both isotypes have identical antigen-binding Fab domains, and both pair with Igα/β chains to transduce signals into the cell, it has been unclear what unique functions they may serve. Interestingly, recent work suggests that IgD may be specialized to mediate tonic survival signals in B cells. B cells lacking either isotype can develop, survive, and mount immune responses, albeit with slightly different efficiency [19–21]. However, these single isotype-deficient B cells express compensatorily higher levels of the remaining BCR isotype, leaving open the question of whether IgM and IgD make differential contributions to B cell survival when expressed at physiological levels. Recently, a novel mouse mutant which lacks surface IgD expression, dmit, was identified via an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-mutagenesis screen [22]. In dmit mice an Ile81Lys substitution is thought to prevent appropriate folding of the constant domain of IgD heavy chain into a comformation needed to pair with light chains. However, it is presumed that misfolded IgD in dmit B cells can nevertheless compete with IgM for binding to Igα/β (CD97α/β) and therefore cell-surface IgM expression is unaltered relative to wild type. As a result, total surface BCR levels in dmit B cells are approximately one third that of wild type cells. dmit B cells are at a significant disadvantage when placed in competition with wild type B cells, suggesting that IgD expression promotes B cell survival. Consistent with this observation, a similar trend was originally observed in IgM+/− mice in which IgD-only B cells have a competitive advantage relative to IgM-only B cells [19].

IgHEL BCR Tg B cells downregulate IgM but not IgD when they develop in the presence of soluble cognate HEL antigen [23]. They have a very short half-life when placed in competition with “wild type” B cells, due to their greater dependence upon limiting amounts of the survival factor BAFF [24,25]. Although these cells experience “too much”, rather than “too little”, BCR signaling, IgD expression has been shown to promote their survival [22]. IgM, but not IgD, is downregulated on naturally occurring auto-reactive follicular B cells as well [15,26–28]. Although not directly tested to date, IgD may be especially critical to retain such IgMlo cells in the follicular B cell compartment in order to avoid “holes” in the mature BCR repertoire.

Although surface IgD promotes B cell survival, whether it does so merely by virtue of expression level, or also because of unique signaling properties is uncertain. IgD is more densely clustered on the cell surface than IgM into separate “islands” and is distinctly associated with co-receptors such as CD19, suggesting that these isotypes might exhibit qualitative differences in downstream signal transduction as well [29,30]. Since CD19 couples the BCR to the PI3K survival pathway, IgD and IgM may differentially support B cell survival independent of antigen sensing and surface expression. Recently, it has been shown that a unique, long, and flexible hinge region in IgD (that is absent in IgM) renders this isotype insensitive to monomeric antigens [31]. Although the nature of endogenous antigens is not well-understood, this might suggest that IgD is less responsive to endogenous antigens than IgM. However, subsequent work from Goodnow and colleagues has shown that IgHEL BCR Tg B cells expressing either IgD or IgM alone are competent to signal in vitro in response to the monovalent protein antigen HEL, and to induce a functional and gene expression program characteristic of anergy in vivo [22,32]. Future work will be needed to define the relative sensitivity of IgD and IgM to bona fide endogenous antigens, and to elucidate qualitative differences in downstream signal transduction.

There is accumulating evidence that distinct BCR isotypes generated by class switch recombination exhibit different degrees of tonic signaling; in recent work, the IgE BCR has been shown to signal more strongly than other isotypes in a constitutive, and antigen-independent manner [33,34]. This facilitates plasma cell differentiation in vitro, and serves to divert activated IgE-expressing B cells from participating in the germinal center response. This is thought to limit the generation of IgE-secreting affinity-matured long-lived plasma cells, and to protect the host from the risk of anaphylaxis posed by secreted IgE.

Lymphocyte development and selection: setting the stage for self-recognition

The TCR’s affinity for self is set in the thymus. Developing thymocytes rearrange their TCRα and β chains to generate a functional receptor, and some of these rearranged TCRs are reactive against self-antigen. This TCR is “tested” for recognition of self pMHC, a key mechanism of central tolerance. Cells with TCRs capable of recognizing self (that can productively generate a TCR-Ras signal) are positively selected, but cells bearing TCRs with very high affinity for self (auto-reactive cells) are either negatively selected and die, or are agonist-selected to become regulatory T cells (Tregs), CD8αα intra-epithelial lymphocytes (IELs), or invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells [35]. ‘Single positive’ (SP4 and SP8) thymocytes that pass these developmental checkpoints exhibit a range of self-reactivity, and thus the T cell pool consists of cells with different degrees of tonic TCR signaling. This leads to a heterogeneous peripheral naïve T cell compartment comprised of T cells with TCRs of varying specificities and affinities for self.

Whether positive selection similarly skews the BCR repertoire towards self-antigen recognition has been challenging to address experimentally. Certainly, BCR signaling is critical for B cell development in the bone marrow and spleen [36–38]. Indeed, mutation of the tyrosine kinase Syk, which is essential for BCR signal transduction, results in a complete block in B cell maturation that is not rescued by over-expression of Bcl-2, implying that the BCR supplies critical differentiation as well as survival signals [39]. However, it has been unclear from studies of mice with BCR signaling mutations whether antigen is required or whether purely tonic BCR signals are sufficient for splenic follicular B cell development [12,14,40,41]. Certainly, antigen-driven selection into the innate-like B-1a compartment is well-appreciated, while strong BCR signaling disfavors adoption of marginal zone B cell fate [13,42–44]. Prior work has supplied indirect evidence for antigen-dependent positive selection of follicular B cells [12,14,40]; studies have shown that self-ligands can drive selection of B cells into the mature primary immune repertoire [45] and analysis of antigen receptor repertoire diversity has revealed a restricted repertoire in mature relative to immature B cells [46–48]. Regardless of whether self-reactivity is actively selected, it persists in the mature naïve follicular B cell pool, drives downregulation of surface IgM expression, and likely influences “tonic” BCR signaling across the mature naïve B cell repertoire [15,49].

The early days of tonic signals in T cells: what is their function?

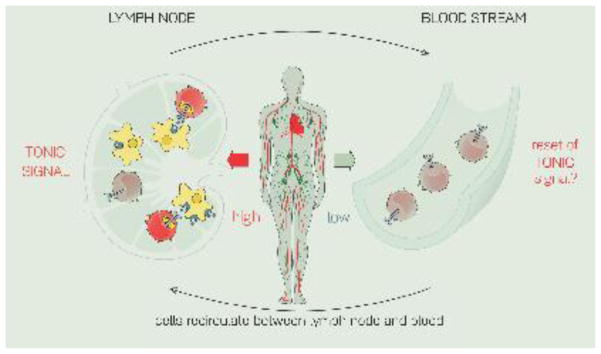

The TCRs of resting T cells make transient contacts with self-pMHC as they survey the peripheral lymphoid organs [50,51]. These contacts do not trigger canonical TCR signaling and T cell activation, but instead generate tonic, sub-threshold signals as defined above. Early work characterizing this tonic pathway identified low-level phosphorylation of proximal TCR signaling components such as the TCRζ chain immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) in resting T cells [4], and constitutive Zap70 association with pTCRζ (phospho-TCRζ) in the basal state [5]. When cells are deprived of these tonic signals, such as when being rested ex vivo in PBS at 37°C [4,52] or when an MHC class II blocking antibody is administered to mice [53], a loss of basal phospho-TCRζ levels can be observed. Similarly, T cells isolated from blood do not exhibit biochemical evidence of tonic signaling [53]. These observations support a model in which pMHC-TCR contacts in peripheral lymphoid organs drive tonic signals in T cells that decay when they enter the circulation, and reappear when they return to lymphoid organs, in a cyclical pattern (Figure 2). In the circulation, T cells may receive different tonic signals, such as from S1P produced by lymphatic endothelial cells, which was recently shown to promote T cell survival in the circulation by maintaining T cell mitochondrial function [54].

Figure 2. T cells receive tonic signals in lymphoid organs but not in the bloodstream.

T cells in peripheral lymphoid organs (PLOs) are in a surveying mode and make transient contacts with self-pMHC. These contacts generate a low-level, constitutive signal (“tonic signal”). In contrast, cells in the bloodstream do not make these contacts with self, and are deprived of tonic signals. It is unknown whether the tonic signal “resets” as lymphocytes transit from the PLOs to the blood and back again.

The function of tonic TCR signaling has been elusive and controversial. A pair of conflicting studies published in the early 2000s argued that tonic signals in T cells “tune” their reactivity to antigen. Bhandoola and colleagues studied T cells that were deprived of tonic signals and suggested that such signals desensitize the TCR (by recruiting negative regulators, thereby raising the threshold required for activation) [55]. Stefanova and colleagues took a similar approach but reported that interactions with self-pMHC sensitize the TCR to antigen, lowering its activation threshold [51]. In sum, tonic TCR signals are evident in T cells, fluctuate in a cyclical manner as T cells circulate into and out of lymphoid organs, and likely impact the sensitivity of the TCR for bona fide foreign antigen encounter.

Ablating the TCR: a maintenance role for tonic TCR signals

Ablation of the BCR results in very rapid loss of B cells [6]. Unlike in B cells, tonic TCR signaling does not appear to be essential for T cell survival per se [56]. Inducible deletion of the TCR by treating Cαfl/fl Mx-Cre (Cre-Lox system) mice with poly(I):poly(C) (pI:C) does not result in rapid loss of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. However, TCR-mediated tonic signals do contribute to T cell homeostasis and maintenance; T cells with deleted TCRs are gradually lost over time, with half-lives of 46 and 16 days for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively [56] (Figure 1). In the case of CD4+ T cells, this TCR-mediated tonic maintenance signal was shown to require MHC class II; when a WT B6 thymus is engrafted into a thymectomized Rag2−/− class II−/− recipient, CD4+ T cells initially populate the periphery normally, but over time the pool of CD4+ T cells decreases more rapidly in the Rag2−/− class II−/− recipients compared to Rag2−/− class II+/+ recipients. Surprisingly, peripheral T cells in the class II-deficient environment undergo proliferation as expected upon transfer in a lymphopenic environment, as measured by Brdu incorporation, and express a diverse set of TCRs as measured by Vα2 usage, even at 6 months following engraftment. However, not all cell-surface markers are normally expressed; for example, CD4+ T cells in a class II-deficient environment fail to upregulate CD44 with age, suggesting that tonic TCR-class II interactions may impact the activation state of the cells as well. The naïve T cell marker CD62L does decrease as expected in these animals, so the low CD44 expression does not reflect a lack of memory-cell subsets appearing [57]. We return to CD44 later in this review.

Similarly, maintenance of naïve CD8+ T cells requires specific MHC class I molecules, as H–Y TCR transgenic cells are lost after transfer into recipients deficient for relevant MHC class I (H-2Db- or H2-Db- β2m−). Interestingly, this decay is much more rapid than that of CD4+ T cells transferred into a class II-deficient host (Figure 1). Unlike CD4+ T cells, transferred CD8+ T cells do not incorporate Brdu in the absence of class I (i.e. antigenic stimulation), indicating a requirement for self-recognition for homeostatic proliferation of CD8+ T cells [58]. This difference may contribute to more rapid loss of CD8 than CD4 T cells in the absence of tonic antigen receptor signaling, and lack of homeostatic proliferation by B cells may render them especially dependent upon tonic survival signaling.

When the TCR is ablated from all T cells by treating Mx1-Cre Tcrafl/fl mice with pI:C [59] or ablated specifically in Treg cells by treating FoxP3-CreERT2 Tracfl/fl mice with tamoxifen [60], a reduced number of Tregs is observed. These TCR-deficient Tregs do not proliferate and lose expression of activation markers, suggesting that tonic TCR signals are important for maintenance of Tregs. These TCR-deficient Tregs lose their suppressive capabilities yet still maintain Treg “lineage-specifying” characteristics such as expression of the transcription factor FoxP3, Treg-specific DNA methylation patterns, and constitutive IL-2 receptor signaling. So, tonic signals appear more important for Treg survival than for maintenance of Treg “identity.” [59,60] (Figure 1).

Reporters of tonic signaling pave the way

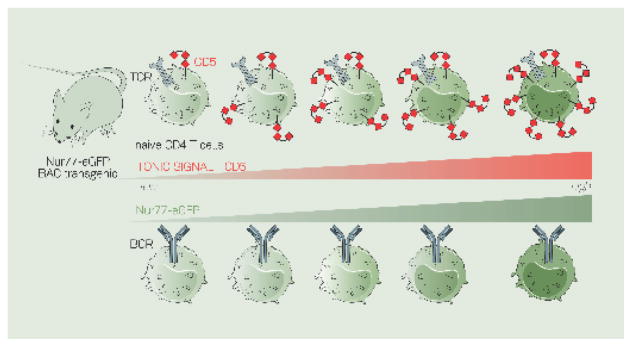

TCRs with varying affinity for self generate a range of tonic signals [8]. Two markers that read-out the level of tonic signaling, or the level of TCR affinity for self, have greatly facilitated our ability to perform functional studies comparing cells with different levels of tonic signaling. These markers are the surface glycoprotein CD5 [50], a negative regulator of TCR signaling, and the orphan nuclear hormone receptor Nur77 [15,61] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. CD5 and Nur77-eGFP report the level of tonic signaling in B and T cells.

CD5 is a surface glycoprotein expressed on T cells and the level of CD5 corresponds to the level of tonic signal - and thus the level of affinity for self by a particular T cell. CD5 is only expressed on a subset of B cells called B-1a B cells, but does not appear to mark the level of tonic signaling in B cells.

Nur77 (Nr4a1) is an immediate-early gene that gets induced proportionally to the level of signal in both T- and B- cells. BAC-transgenic mice were generated in which eGFP is under control of the Nur77 regulatory region. The level of GFP reads-out the level of tonic signal a B or T cell receives.

Surface CD5 expression is upregulated proportionally to TCR signal strength during thymic selection on double-positive thymocytes, and single-positive thymocytes express CD5 at levels that correspond to TCR avidity. Maintenance of CD5 levels on thymocytes, as well as on both CD4+ and CD8+ peripheral T cells, requires self-pMHC interactions [50]. Recent studies in which naïve CD4+ cells were sorted based on the level of CD5 revealed that CD5high cells had higher levels of pTCRζ compared to CD5low cells [8], as well as higher levels of phosphorylated S6 and ERK kinases, which lie downstream in the mTOR-S6 and RAF-MEK-ERK kinase pathways, respectively [52].

Nr4a1 (encoding Nur77) is an immediate-early gene that is rapidly upregulated by TCR stimulation in thymocytes and T cells, and by BCR stimulation in B cells. Two independent groups, including our own, generated Nur77-eGFP BAC transgenic mice, in which enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) is under control of the Nr4a1 regulatory region [15,61]. The level of induced GFP reports the integrated strength of TCR and BCR signaling in vitro and in vivo [15,61–64]. GFP expression is also induced in vivo in thymocytes that have undergone signaling-dependent checkpoints during selection, and in developing splenic transitional B cells [15,61]. Modulation of TCR and BCR signal strength in the basal state by genetic perturbation of surface CD45 expression leads to concomitant changes in GFP expression [15,65]. Importantly, transfer of reporter T cells into hosts that lack MHC class II expression leads to gradual loss of GFP expression, suggesting that continuous “tonic” signals in T cells require encounter with MHC-self-peptide complexes in vivo [61]. Similarly, elimination of endogenous antigen recognition leads to loss of GFP expression in naïve reporter B cells [15]. Peripheral naïve mature follicular B cells, as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, exhibit a range of GFP expression that corresponds to a continuum of self-reactivity and “tonic” antigen receptor signaling, and in the case of follicular B cells, downregulation of the IgM BCR [15,61]. Perhaps unsurprisingly, CD5 levels correlate with Nur77-eGFP expression in CD4+ and CD8+ naïve T cells [9] (Figure 3). The CD5 and Nur77-eGFP BAC transgenic tools have sparked a great deal of interest in deciphering how the level of tonic signal impacts immune function in health and disease.

Tonic signaling and peripheral T cell fitness

Recently, several studies have begun to more clearly define the physiological role of these basal signals in several T cell subsets, including CD4+ conventional T cells [8,52], CD8+ cytotoxic T cells [9], and CD4+ regulatory T cells [59,60].

CD5high T cells stimulated with the synthetic DAG analog phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) exhibit increased phosphorylation of ERK and produce more IL-2 than PMA-stimulated CD5low cells [66]. Tetramer studies reveal that CD4+ conventional T cells with high tonic signaling (CD5high) bind to foreign antigen better than their CD5low counterparts, suggesting that the degree of affinity for self-antigen parallels the degree of affinity for foreign antigen. When congenically marked CD8+ T cells, sorted into CD5low and CD5high, are transferred into recipients prior to infection with influenza A, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus Armstrong (LCMV), or Listeria monocytogenes (LM), the CD5high cells expand much more than their CD5low counterparts [9]. This suggests that cells with high tonic signaling contribute more to the immune response to infection than lower-affinity cells. These experiments were performed with polyclonal T cells, and as such the TCRs in the repertoire display a range of affinities for self. It will be important to determine how much of the difference in functional response is attributable to TCR specificity, and how much is due to differences in tonic signal transduction machinery. Functional differences between Nur77-eGFPhigh and Nur77-eGFPlow cells have not been explored yet. These data suggest that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with high tonic signaling dominate in the immune response to infection.

Treg cells with different degrees of self-reactivity have also been shown to have distinct functional roles in vivo. A recent publication from Ed Palmer’s group [67] demonstrated that expression levels of CD25, PD-1, and GITR reflect populations of Tregs with different degrees of self-reactivity: Triplehi Treg (high expression of all three mentioned markers) had increased CD5 and Nur77-GFP levels compared to Triplelo Tregs (low expression of these markers). Using B3K508 TCR transgenic T cells (that recognize peptides of different affinities), the Palmer group showed that ligands at the threshold of negative selection generate Triplelo cells, whereas very high-affinity peptides select Triplehi cells, suggesting that these two populations differ in their degree of affinity for self. These cells are maintained in vivo by self (and not foreign) antigens, as this population persists in antigen free mice, which lack infectious, microbial and dietary antigens. Functionally, self-reactive Tregs (Triplehi) proliferated more in vivo and were more suppressive than Triplelo cells, whereas these lower affinity cells facilitated the conversion of conventional T cells into iTregs in a colitis model, although the mechnanism underlying this conversion has not yet been identified [67]. Collectively, these data suggest that the degree of self-reactivity in CD4+ conventional T cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ regulatory T cells impacts their functional ability to respond to infection and control immune responses.

Towards a tonic signaling pathway: insights from the adapter molecule LAT

The linker for activation of T cells (LAT) is a transmembrane adapter protein involved in proximal TCR signaling. LAT is phosphorylated at multiple tyrosine residues in response to TCR crosslinking and this leads to the recruitment of downstream signaling molecules that mediate full T cell activation. LAT-deficient mice, or mice where the four tyrosines are mutated, exhibit a severe block in thymocyte development and lack peripheral T cells [68,69]. One of the tyrosines (Y136 in mice) serves as a docking site for PLCγ1, which generates the second mesengers diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol trisphosphate (IP3) that activate Ras and calcium signaling, respectively. Mice harboring a Y136F mutation revealed an intriguing phenotype; they have a severe (yet incomplete) block in thymocyte development, but T cells populate the peripheral lymphoid organs and greatly expand over time. LATY136F (also referred to as LATm/m here) mice develop lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, their CD4+ T cells have an activated phenotype (CD44hi CD62Llo), and these T cells produce high levels of the Th2 cytokine interleukin 4 (IL-4) even without ex vivo restimulation [70,71].

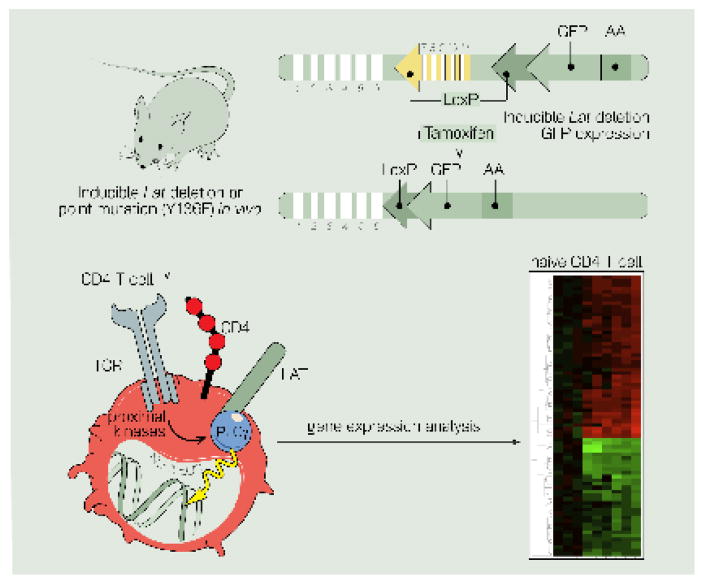

Elegant genetic mouse models revealed the very surprising observation that the Th2 hyperproliferative syndrome also occurs when LAT is inducibly deleted or mutated exclusively in peripheral T cells. The first of these is the Latflox-dtr/Y136F model [72], where one allele is floxed and has the diphtheria toxin receptor knocked into the 3′ untranslated region, and the other allele contains the knocked-in Y136F mutation; cells from these mice are retrovirally transduced with Cre and are diphtheria-toxin treated prior to transfer into recipients. In the second model, Cre-ER+ expressing mice with one floxed allele and one null or mutant allele (LATf/− or LATf/m) are treated with tamoxifen [73] (Figure 4). This indicates that the Th2 lymphoproliferation phenotype is not due to altered thymocyte development and selection defects, and instead implicates LAT in control of peripheral CD4+ T cells. Moreover, T cells from LATY136F mice are refractory to ex vivo stimulation through the T cell receptor (with α-CD3/CD28), displaying an inability to flux calcium, proliferate, and secrete IL-2 [71,72]. Paradoxically, T cells lacking functional LAT nevertheless display an aberrantly activated, differentiated, and proliferative phenotype. These studies suggest that the LAT-PLCγ1 interaction is vital for transmitting a low-level, tonic signal, and that loss of this tonic signal somehow is permissive for spontaneous T cell activation and differentiation.

Figure 4. Inducible deletion of LAT in T cells reveals a role for tonic signals in controlling gene expression.

Cartoon of genetic mouse model with exons 7 to 11 of LAT flanked by LoxP recombination sites. Crossing these mice to Cre-ER allows for inducible deletion of LAT upon administration of tamoxifen to release the Cre recombinase from the estrogen receptor (ER). Studies using this inducible model revealed a role for tonic TCR-LAT-PLCγ signals in controlling gene expression in CD4 T cells.

Tonic LAT signals and gene expression regulation

We used the adapter molecule LAT as an entry point to uncover what cellular functions might depend on tonic signals. We previously observed that tonic TCR signals can control gene expression levels [10,74]. We showed that a Jurkat line deficient for the adapter LAT (J.CaM2), and thus lacking LAT-dependent tonic signals, exhibited unique changes in gene expression at steady state in the absence of TCR ligation. These gene expression arrays performed with unstimulated Jurkat cells, as well as primary mouse thymocytes, revealed a LAT-dependent tonic pathway that represses transcription of the Rag-1 and Rag-2 genes. Inhibitor studies showed that PLCγ1, PI3K, PKC, calcineurin and MEK can participate in this LAT-dependent tonic pathway, leading to the basal phosphorylation of the MAPK effector kinase ERK [10]. We also observed that LAT-dependent tonic signals maintain expression levels of other genes; J.CaM2 cells have reduced TCR/CD3 surface levels, due to reduced TCRα transcripts. Similarly, peripheral CD4+ T cells from the above-described [73] mice where LAT is inducibly deleted for 4 weeks (Cre-ER+ LATf/−) have reduced levels of surface TCR and lose TCRα transcripts over time [74]. Intriguingly, treatment of J.CaM2 cells with trichostatin A (TSA), an inhibitor of class I and II histone deacetylases (HDACs), increased the levels of TCRα and TCRβ transcripts [74]. This result suggested that a tonic LAT signaling pathway maintains gene expression programs in naïve T cells by modulating the activity of HDACs, a class of epigenetic modifiers that de-acetylate histone tails, leading to gene repression [75]. (Figure 4).

We recently delineated a biochemical mechanism by which tonic signals through LAT maintain gene expression [76]. Microarray analysis of CD4+ T cells with WT LAT or with 1-week of induced LAT deletion or Y136F mutation revealed a cluster of genes that were strongly downregulated with LAT perturbation. Interestingly, these genes included the immediate early response genes Egr1, Egr2, and Egr3, Irf4, as well as Nr4a1 (encoding Nur77), Nr4a2, and Nr4a3. Several of these genes, including Nr4a1, have been shown to be targets of the epigenetic repressor histone deacetylase 7 [77,78] (Figure 4). We found that tonic signals through LAT constitutively phosphorylate HDAC7, leading to constant nuclear export of HDAC7. In the absence of LAT, HDAC7 is now dephosphorylated and localized to the nucleus, where it represses its target genes. This tonic LAT-HDAC7-gene expression pathway is important for T cell homeostasis, as lower levels of Nr4a1 increase T cell proliferation and reduced Irf4 expression leads to increased Th2-cytokine production, two key features of the LATY136F mouse pathology described above [76].

Setting the tone upstream of LAT

It has long been known that treatment of resting T cells with pervanadate to inhibit cellular phosphatases produces robust phosphorylation of multiple substrates [79], suggesting that the basal state of resting T cells is not static, but rather reflects a dynamic balance between kinases and phosphatases. Phosphorylation of the TCRζ chain ITAMs, recruitment of Zap-70, and further downstream signaling to the LAT signalosome is absolutely dependent upon the T cell-specific Src family kinase (SFK) Lck. Enzymatic activity of Lck is tightly regulated by two critical regulatory tyrosines; phosphorylation of the activation loop tyrosine Y394 is essential for maximal kinase activity, while phosphorylation of the C-terminal inhibitory tyrosine favors adoption of a closed, inactive conformation [80].

Lck Y505 is under continuous reciprocal regulation in the basal state by the receptor-like tyrosine phosphatase CD45 and the kinase Csk. Progressive reduction of surface CD45 expression (in an allelic series of mice) results in increased Lck Y505 phosphorylation, and consequently reduced zeta chain phosphorylation and surface CD5 expression at steady state [65]. Remarkably, concomitant reduction of Csk expression restores the balance between CD45 and Csk, and normalizes surface CD5 expression on thymocytes. Conversely, acute inhibition of Csk kinase activity is sufficient to activate Lck in T cells harboring an analog-sensitive allele of Csk [81,82]. Titration of CD45 expression similarly regulates basal phosphorylation of the C-terminal inhibitory tyrosine of the SFK Lyn in B cells [83,84]. However, the role of Csk in regulation of basal BCR signaling remains to be elucidated, and the balance between CD45 and Csk in B cells is made complex by the dual positive and negative regulatory role played by Lyn in B cells [85]. Although basal TCR signaling plays critical roles in regulating T cell maintenance, and T cell gene expression, it is not immediately apparent why regulation of basal signaling in T cells is wired to be so dynamic (For a more detailed, recent review focused on the dynamic balance between CD45 and Csk, please see [11]).

Tonic signals downstream of LAT

The Ras guanine nucleotide releasing protein 1 (Rasgrp1) is a Ras activator that is highly expressed in thymocytes and T cells [86]. From Jurkat T cell line studies, we had suspected that Rasgrp1 may perform a tonic signaling function; indeed the Rasgrp1-low (10% of WT levels) Jurkat line JPRM441 has reduced TCRα and TCRβ transcript levels at steady state [74]. We recently stumbled on a tonic mTOR-S6 signaling pathway in CD4+ T cells through the analysis of Rasgrp1Anaef mice [52] (Figure 5), which carry a single nucleotide substitution leading to the missense variant R519G.

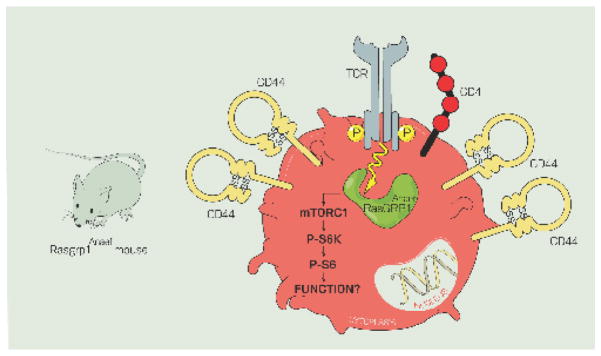

Figure 5. The Rasgrp1Anaef variant generates increased tonic mTORC1-S6 signals that drive T cell autoreactivity.

Analysis of mice with a point-mutated Rasgrp1 variant (Rasgrp1Anaef) revealed that increased tonic Rasgrp1-mTORC1 signals drive elevated CD44 expression on T cells, which can be reduced by in vivo administration of the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin.

Tonic mTOR signals

As fully Rasgrp1-deficient animals have a profound block in T cell development and peripheral T cell lymphopenia [87], this model cannot be used to study the potential role of Rasgrp1 in peripheral T cell tonic signaling. Rasgrp1Anaef mice, generated through ENU-mutagenesis, provided such an opportunity. Thymocyte selection is surprisingly efficient in Rasgrp1Anaef despite defective ERK signaling in response to in vitro TCR stimulation of Rasgrp1Anaef thymocytes [52]. As such, T cells populate the peripheral lymphoid organs, and these animals are never lymphopenic. Characterization of Rasgrp1Anaef mice revealed features of T cell autoreactivity and autoimmunity that becomes more prominent with age [52]. T cells from Rasgrp1Anaef mice uniformly express elevated levels of the activation marker CD44 on all CD4+ T cells, regardless of CD62L expression, whereas other activation markers CD25 and CD69 are expressed at normal levels (Figure 5). Follicular helper T cells spontaneously arise in unimmunized Rasgrp1Anaef mice, and T cells aberrantly stimulate B cells to produce anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA). Since CD44 had been shown to be a target of mTOR [88], we explored the idea that elevated basal mTOR signaling may be responsible for the autoimmune features in these animals. It had been noted that mouse thymocytes and T cells stimulated through the TCR or with PMA activate the mTOR pathway, and this requires Rasgrp1 [89]. Interestingly, this study also showed that phosphorylation of known mTOR-targets S6, 4E-BP1 and Akt were reduced in unstimulated Rasgrp1-deficient thymocytes compared to WT. This work already suggests that Rasgrp1 signals to mTOR in a tonic fashion as well as in a TCR-inducible one. Thymocytes and T cells of Rasgrp1Anaef mice exhibit elevated levels of basal P-S6 (S235/236) and pharmacological inhibition of mTOR (with rapamycin) in vivo reduces CD44 levels on thymocytes [52]. This elevated basal mTOR signaling is responsible for the autoimmune features in these animals; Genetic complementation by crossing Rasgrp1Anaef mice to mTORchino mice, an mTOR variant that has reduced mTOR-S6 signaling, resolves the spontaneous ANA- and Tfh-features [52]. Thus, aberrantly increased tonic Rasgrp1-mTOR signals result in autoimmune features (Figure 5).

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

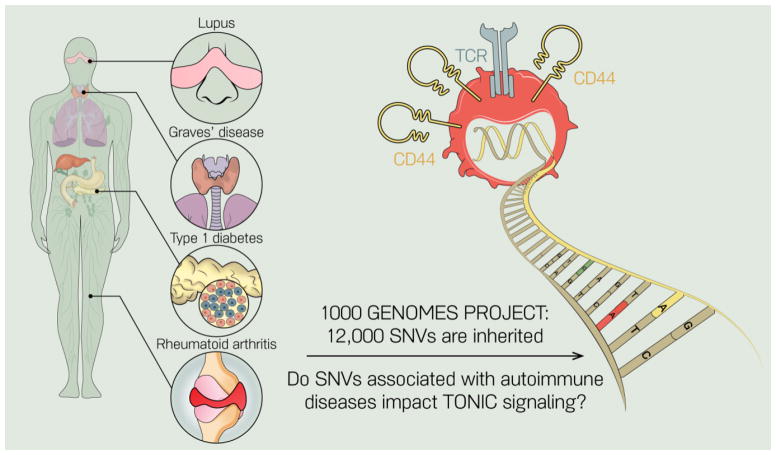

In addition to previously defined roles for tonic signaling in lymphocyte survival, we highlight recent literature that has identified a role for tonic TCR signaling in regulating adaptive immune responses, and perhaps most critically, in maintaining inhibitory tone on naïve T cells. Several mouse models have been published wherein single nucleotide changes in signaling genes lead to breaks in immune tolerance and development of autoimmunity: the LATY136F and Rasgrp1Anaef models discussed above are two examples. It is now becoming more and more clear that these mutations impact tonic signaling pathways. Throughout the text we have pointed out that there are many questions unresolved in the field of tonic signaling (see “Outstanding Questions” box). We are very interested in dissecting how genetic variation in people may impact tonic signaling. Given that the typical human genome contains 10 to 12 thousand missense gene variants [90], understanding how subtle changes in signaling proteins impact immune cell homeostasis will be critical for our full understanding of the molecular basis of autoimmunity (Figure 6). Overall, we propose that tonic signaling, and its influence on the basal state of immune cells, should be considered as we move forward with sophisticated treatments for autoimmune diseases and other diseases in which immunotherapies play a role.

OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS BOX.

Why are tonic signals in T cell not simply survival cues as in B cells?

Do tonic signals in B cells have additional functions besides ensuring B cell survival?

Do tonic signals in T cells have a cyclic pattern when T cells travel between peripheral lymphoid organs and circulation?

Why is the regulation of basal signaling in T cells wired to be so dynamic, for instance through the dynamic CD45/Csk balance?

What signaling molecules do tonic signals in T cells operate through?

Tonic signals through the adapter LAT control gene expression. Do these tonic pathways control additional cellular functions?

What is the function of tonic mTOR signals in T cells and what does it mean when these mTOR signals are enhanced?

Do human SNVs in signaling molecules alter tonic signals in T cells and contribute to autoimmune diseases?

Figure 6. Hypothesis that single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in signaling genes impact tonic signals and cause T cell autoimmunity.

Several mouse models have been described in which single point mutations that lead to amino acid changes (SNVs) in signaling molecules can lead to autoimmune features. The LAT and Rasgrp1 models described reveal that these SNVs can alter tonic signaling in T cells. Since every person inherits 12,000 SNVs on average, it is likely that some of these SNVs impact tonic signaling in human T cells and contribute to autoimmunity.

TRENDS BOX.

T- and B- lymphocytes exhibit low-level, constitutive signaling in the basal state (“tonic signaling”). Tonic signals are essential for the survival of B cells whereas the functional role of tonic signals in T cells is still being worked out.

Surface CD5 expression levels as well as the genetic Nur77-eGFP reporter are tools that have recently been exploited as markers of affinity for self and tonic signaling. B- and T- cells exhibit a range of self-reactivity in the basal state

Functionally, tonic signals in CD4 and CD8 T cells serve a maintenance function, and cells with high tonic signals perform better in an immune response. Tonic signals in regulatory T are critical for their suppressive capacity.

Mouse models with single point mutations in signaling molecules display altered tonic signals and autoimmune features and have aided mapping of tonic signaling pathways in T cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anna Hupalowska for creating the illustrations. Our activities are supported by grants from the NSF (1650113 to DRM), the NIH-NIAMS (R01-A127648 to JZ), and the NIH-NIAID (R01-AI104789 and P01-AI091580 to JPR).

GLOSSARY

Cells

- B lymphocyte

B cell, adaptive immune cell that makes antibodies

- CD4+ T cell

Helper T cell

- CD8+ T cells

Cytotoxic T cell

- Double-positive (DP) thymocyte

developing T-lineage cell found in the thymus that expresses both CD4 and CD8 co-receptors

- Regulatory T cell (Treg)

Type of CD4+ T cell that expresses FoxP3 and suppresses immune responses

- Single-positive (SP) thymocyte

T-lineage cell found in the thymus that is more developmentally mature than a double-positive thymocyte and has downregulated one of the co-receptors to express only CD4 or only CD8 (SP4 and SP8, respectively)

- T lymphocyte

T cell, cell of the adaptive immune system

Receptors

- BCR

B cell receptor, the antigen receptor on B lymphocytes comprised of 2 heavy and 2 light chains that encode the antigen-binding domains, and the signaling components Ig α/β.

- Igα/β

cD79 α/β; signaling components of the BCR

- IgD-BCR

Ig (immunoglobulin) D is the product of an alternately spliced BCR heavy chain transcript that contains the Cδ constant domain of the BCR in lieu of Cμ, and is co-expressed with IgM-BCR on transitional and mature follicular B cells prior to activation

- IgE-BCR

Ig (immunoglobulin) E is expressed after class switch recombination of the BCR heavy chain to the downstream Cε constant domain.

- IgHEL

A transgenic BCR that recognizes the protein antigen hen egg lysozyme (HEL) that is not normally expressed in mice, but can be misexpressed in soluble or membrane-bound

- IgM-BCR

Ig (immunoglobulin) M is a primary isotype of the BCR heavy chain that is encoded by recombined VDJ segments coupled to the Cμ constant domain, and is expressed on immature and mature naïve B cells prior to class-switch recombination

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex that presents peptides. Found in two variations, class I and class II

- TCR

T cell receptor, the antigen receptor on T lymphocytes

- TCRζ

Signaling component of the T cell receptor. Contains ITAMs (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs) that can be phosphorylated to initiate proximal TCR signaling

Markers

- CD4

co-receptor expressed on T cells. Recognizes MHC class II

- CD5

surface glycoprotein expressed on peripheral T cells and B1 B cells. Expression levels correlate with affinity for self

- CD8

co-receptor expressed on T cells. Recognizes MHC class I

- CD44

T cell activation marker, expressed on effector/memory T cells

- CD62L

L-selectin, an adhesion molecule that is highly expressed on naïve T cells and is downregulated on antigen-experienced and memory T cells

- Nur77

immediate-early gene downstream of the BCR and TCR. Induced proportional to the level of tonic and inducible antigen receptor signaling

Molecules

- Bcl2

anti-apoptotic protein

- LAT

membrane-bound adapter protein in T cells

- MEK

kinase in the Ras-MAPK (mitogen activated protein kinase) pathway, important for cell growth

- NF-kB

protein complex that has a role in lymphocyte development and survival

- PI3K

lipid kinase that converts PIP2 into PIP3. Role in activating the mTOR pathway

- PLCγ

enzyme that catalyzes the generation of DAG and IP3 from PIP2

- RasGRP1

Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor highly expressed in T cells. Exchanges GDP for GTP on Ras

- Syk

tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates ITAMs on the BCR Iga/b chains to initiate BC R signal transduction

Technical terms

- Antigen-free mice

animals that are weaned from germ-free mothers so they lack microbial antigens (do not have a microbiome), and they are fed an elemental diet of glucose and amino acids so they are not exposed to any dietary antigens

- Cre-Lox

system for inducible mutagenesis. LoxP recombination sites flank a gene, and upon expression of the recombinase Cre, the DNA sequence between the LoxP sites is excised. Cre can be driven under the control of a specific promoter, allowing for cell-type specific deletion. Cre can also be bound to a ligand-binding domain of the estrogen receptor and only accesses the nucleus to execute recombination when tamoxifen, a ligand for the estrogen receptor, is administered

- ENU Mutagenesis

treatment of mouse sperm with ENU, a chemical mutagen, generates random DNA mutations. Offspring can be screened for phenotypic properties and whole genome sequencing can identify the mutated gene

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kurosaki T. Regulation of BCR signaling. Molecular Immunology. 2011;48:1287–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane LP, et al. Signal transduction by the TCR for antigen. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2000;12:242–249. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myers DR, Roose JP. Kinase and Phosphatase Effector Pathways in T cells. In: Ratcliffe Michael., editor. Encyclopedia of Immunobiology. III. 2016. pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Oers NS, et al. Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of the T-cell receptor (TCR) zeta subunit: regulation of TCR-associated protein tyrosine kinase activity by TCR zeta. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5771–5780. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Oers NS, et al. ZAP-70 is constitutively associated with tyrosine-phosphorylated TCR zeta in murine thymocytes and lymph node T cells. Immunity. 1994;1:675–685. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam KP, et al. In vivo ablation of surface immunoglobulin on mature B cells by inducible gene targeting results in rapid cell death. Cell. 1997;90:1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivasan L, et al. PI3 Kinase Signals BCR-Dependent Mature B Cell Survival. Cell. 2009;139:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandl JN, et al. T Cell-Positive Selection Uses Self-Ligand Binding Strength to Optimize Repertoire Recognition of Foreign Antigens. Immunity. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulton RB, et al. The TCR’s sensitivity to self peptide–MHC dictates the ability of naive CD8+ T cells to respond to foreign antigens. Nat Immunol. 2014;16:107–117. doi: 10.1038/ni.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roose JP, et al. T Cell Receptor-Independent Basal Signaling via Erk and Abl Kinases Suppresses RAG Gene Expression. Plos Biol. 2003;1:e3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan YX, et al. Novel tools to dissect the dynamic regulation of TCR signaling by the kinase Csk and the phosphatase CD45. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2013;78:131–139. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2013.78.020347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancro MP, Kearney JF. B cell positive selection: road map to the primary repertoire? J Immunol. 2004;173:15–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cariappa A, Pillai S. Antigen-dependent B-cell development. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2002;14:241–249. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su TT, et al. Signaling in transitional type 2 B cells is critical for peripheral B-cell development. Immunol Rev. 2004;197:161–178. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zikherman J, et al. Endogenous antigen tunes the responsiveness of naive B cells but not T cells. Nature. 2012;489:160–164. doi: 10.1038/nature11311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosado MM, Freitas AA. The role of the B cell receptor V region in peripheral B cell survival. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2685–2693. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199809)28:09<2685::AID-IMMU2685>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blum JH, et al. Role of the mu immunoglobulin heavy chain transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains in B cell antigen receptor expression and signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:27236–27245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radaev S, et al. Structural and functional studies of Igalphabeta and its assembly with the B cell antigen receptor. Structure. 2010;18:934–943. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lutz C, et al. IgD can largely substitute for loss of IgM function in B cells. Nature. 1998;393:797–801. doi: 10.1038/31716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nitschke L, et al. Immunoglobulin D-deficient mice can mount normal immune responses to thymus-independent and -dependent antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1887–1891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roes J, Rajewsky K. Immunoglobulin D (IgD)-deficient mice reveal an auxiliary receptor function for IgD in antigen-mediated recruitment of B cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:45–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabouri Z, et al. IgD attenuates the IgM-induced anergy response in transitional and mature B cells. Nat Comms. 2016;7:13381. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodnow CC, et al. Induction of self-tolerance in mature peripheral B lymphocytes. Nature. 1989;342:385–391. doi: 10.1038/342385a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesley R, et al. Reduced competitiveness of autoantigen-engaged B cells due to increased dependence on BAFF. Immunity. 2004;20:441–453. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thien M, et al. Excess BAFF Rescues Self-Reactive B Cells from Peripheral Deletion and Allows Them to Enter Forbidden Follicular and Marginal Zone Niches. Immunity. 2004;20:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duty JA, et al. Functional anergy in a subpopulation of naive B cells from healthy humans that express autoreactive immunoglobulin receptors. J Exp Med. 2009;206:139–151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchenbaum GA, et al. Functionally responsive self-reactive B cells of low affinity express reduced levels of surface IgM. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:970–982. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quach TD, et al. Anergic Responses Characterize a Large Fraction of Human Autoreactive Naive B Cells Expressing Low Levels of Surface IgM. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;186:4640–4648. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maity PC, et al. B cell antigen receptors of the IgM and IgD classes are clustered in different protein islands that are altered during B cell activation. Science Signaling. 2015;8:ra93. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattila PK, et al. The actin and tetraspanin networks organize receptor nanoclusters to regulate B cell receptor-mediated signaling. Immunity. 2013;38:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Übelhart R, et al. Responsiveness of B cells is regulated by the hinge region of IgD. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:534–543. doi: 10.1038/ni.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brink R, et al. Immunoglobulin M and D antigen receptors are both capable of mediating B lymphocyte activation, deletion, or anergy after interaction with specific antigen. J Exp Med. 1992;176:991–1005. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Z, et al. Regulation of B cell fate by chronic activity of the IgE B cell receptor. eLife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haniuda K, et al. Autonomous membrane IgE signaling prevents IgE-memory formation. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1109–1117. doi: 10.1038/ni.3508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Germain RN. T-cell development and the CD4-CD8 lineage decision. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2002;2:309–322. doi: 10.1038/nri798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarlinton DM, et al. Continued differentiation during B lymphopoiesis requires signals in addition to cell survival. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1481–1494. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.10.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young F, et al. Constitutive Bcl-2 expression during immunoglobulin heavy chain-promoted B cell differentiation expands novel precursor B cells. Immunity. 1997;6:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miosge LA, Goodnow CC. Genes, pathways and checkpoints in lymphocyte development and homeostasis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:318–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner M, et al. Syk tyrosine kinase is required for the positive selection of immature B cells into the recirculating B cell pool. J Exp Med. 1997;186:2013–2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas MD, et al. Regulation of peripheral B cell maturation. Cellular Immunology. 2006;239:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tussiwand R, et al. Tolerance checkpoints in B-cell development: Johnny B good. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2317–2324. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baumgarth N. B-1 Cell Heterogeneity and the Regulation of Natural and Antigen-Induced IgM Production. Front Immunol. 2016;7:688–689. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casola S, et al. B cell receptor signal strength determines B cell fate. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:317–327. doi: 10.1038/ni1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayakawa K, et al. Positive selection of anti-thy-1 autoreactive B-1 cells and natural serum autoantibody production independent from bone marrow B cell development. J Exp Med. 2003;197:87–99. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang H, Clarke SH. Evidence for a ligand-mediated positive selection signal in differentiation to a mature B cell. J Immunol. 2003;171:6381–6388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levine MH, et al. A B-cell receptor-specific selection step governs immature to mature B cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2743–2748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050552997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu H, et al. Most peripheral B cells in mice are ligand selected. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1357–1371. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freitas AA, et al. Expression of antibody V-regions is genetically and developmentally controlled and modulated by the B lymphocyte environment. Int Immunol. 1989;1:342–354. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wardemann H, et al. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Azzam HS, et al. CD5 expression is developmentally regulated by T cell receptor (TCR) signals and TCR avidity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2301–2311. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stefanová I, et al. Self-recognition promotes the foreign antigen sensitivity of naive T lymphocytes. Nature. 2002;420:429–434. doi: 10.1038/nature01146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daley SR, et al. Rasgrp1 mutation increases naive T-cell CD44 expression and drives mTOR-dependent accumulation of Helios+ T cells and autoantibodies. eLife. 2013;2:e01020. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stefanová I, et al. TCR ligand discrimination is enforced by competing ERK positive and SHP-1 negative feedback pathways. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:248–254. doi: 10.1038/ni895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mendoza A, et al. Lymphatic endothelial S1P promotes mitochondrial function and survival in naive T cells. Nature Publishing Group; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhandoola A, et al. Peripheral expression of self-MHC-II influences the reactivity and self-tolerance of mature CD4(+) T cells: evidence from a lymphopenic T cell model. Immunity. 2002;17:425–436. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Polic B, et al. How alpha beta T cells deal with induced TCR alpha ablation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8744–8749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141218898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takeda S, et al. MHC class II molecules are not required for survival of newly generated CD4+ T cells, but affect their long-term life span. Immunity. 1996;5:217–228. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tanchot C, et al. Differential requirements for survival and proliferation of CD8 naïve or memory T cells. Science. 1997;276:2057–2062. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vahl JC, et al. Continuous T Cell Receptor Signals Maintain a Functional Regulatory T Cell Pool. Immunity. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levine AG, et al. Continuous requirement for the TCR in regulatory T cell function. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:1070–1078. doi: 10.1038/ni.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moran AE, et al. T cell receptor signal strength in Treg and iNKT cell development demonstrated by a novel fluorescent reporter mouse. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2011;208:1279–1289. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Au-Yeung BB, et al. A sharp T-cell antigen receptor signaling threshold for T-cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E3679–88. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413726111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mueller J, et al. Cutting edge: An in vivo reporter reveals active B cell receptor signaling in the germinal center. The Journal of Immunology. 2015;194:2993–2997. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Au-Yeung BB, et al. IL-2 Modulates the TCR Signaling Threshold for CD8 but Not CD4 T Cell Proliferation on a Single-Cell Level. The Journal of Immunology. 2017 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zikherman J, et al. CD45-Csk Phosphatase-Kinase Titration Uncouples Basal and Inducible T Cell Receptor Signaling during Thymic Development. Immunity. 2010;32:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Persaud SP, et al. Intrinsic CD4+ T cell sensitivity and response to a pathogen are set and sustained by avidity for thymic and peripheral complexes of self peptide and MHC. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:266–274. doi: 10.1038/ni.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wyss L, et al. Affinity for self antigen selects Treg cells with distinct functional properties. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni.3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang W, et al. Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity. 1999;10:323–332. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sommers CL, et al. Knock-in mutation of the distal four tyrosines of linker for activation of T cells blocks murine T cell development. J Exp Med. 2001;194:135–142. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aguado E, et al. Induction of T helper type 2 immunity by a point mutation in the LAT adaptor. Science. 2002;296:2036–2040. doi: 10.1126/science.1069057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sommers CL. A LAT Mutation That Inhibits T Cell Development Yet Induces Lymphoproliferation. Science. 2002;296:2040–2043. doi: 10.1126/science.1069066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mingueneau M, et al. Loss of the LAT adaptor converts antigen-responsive T cells into pathogenic effectors that function independently of the T cell receptor. Immunity. 2009;31:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shen S, et al. The essential role of LAT in thymocyte development during transition from the double-positive to single-positive stage. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:5596–5604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Markegard E, et al. Basal LAT-diacylglycerol-RasGRP1 Signals in T Cells Maintain TCRα Gene Expression. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haberland M, et al. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Myers DR, et al. Tonic LAT-HDAC7 Signals Sustain Nur77 and Irf4 Expression to Tune Naive CD4 T Cells. CellReports. 2017;19:1558–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dequiedt F, et al. HDAC7, a thymus-specific class II histone deacetylase, regulates Nur77 transcription and TCR-mediated apoptosis. Immunity. 2003;18:687–698. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kasler HG, Verdin E. Histone Deacetylase 7 Functions as a Key Regulator of Genes Involved in both Positive and Negative Selection of Thymocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5184–5200. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02091-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Garcia-Morales P, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation in T cells is regulated by phosphatase activity: studies with phenylarsine oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9255–9259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hermiston ML, et al. CD45, CD148, and Lyp/Pep: critical phosphatases regulating Src family kinase signaling networks in immune cells. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:288–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tan YX, et al. Inhibition of the kinase Csk in thymocytes reveals a requirement for actin remodeling in the initiation of full TCR signaling. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:186–194. doi: 10.1038/ni.2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Manz BN, et al. Small molecule inhibition of Csk alters affinity recognition by T cells. eLife. 2015:4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zikherman J, et al. Quantitative differences in CD45 expression unmask functions for CD45 in B-cell development, tolerance, and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E3–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117374108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zikherman J, et al. The structural wedge domain of the receptor-like tyrosine phosphatase CD45 enforces B cell tolerance by regulating substrate specificity. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;190:2527–2535. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu Y, et al. Lyn tyrosine kinase: accentuating the positive and the negative. Immunity. 2005;22:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ebinu JO, et al. RasGRP links T-cell receptor signaling to Ras. Blood. 2000;95:3199–3203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dower NA, et al. RasGRP is essential for mouse thymocyte differentiation and TCR signaling. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:317–321. doi: 10.1038/79766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hsieh AC, et al. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature10912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gorentla BK, et al. Negative regulation of mTOR activation by diacylglycerol kinases. Blood. 2011;117:4022–4031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Auton A, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]