Abstract

Objective

To assess whether information about abortion safety and awareness of abortion laws affect voters’ opinions about medically unnecessary abortion regulations.

Study design

Between May and June 2016, we randomized 1,200 Texas voters to receive or not receive information describing the safety of office-based abortion care during an online survey about abortion laws using simple random assignment. We compared the association between receiving safety information and awareness of recent restrictions and beliefs that ambulatory surgical center (ASC) requirements for abortion facilities and hospital admitting privileges requirements for physicians would make abortion safer. We used Poisson regression, adjusting for political affiliation and views on abortion.

Results

Of 1,200 surveyed participants, 1,183 had complete data for analysis: 612 in the information group and 571 in the comparison group. Overall, 259 (46%) in the information group and 298 (56%) in the comparison group believed the ASC requirement would improve abortion safety (p=.008); 230 (41%) in the information group and 285 (54%) in the comparison group believed admitting privileges would make abortion safer (p<.001). After multivariable adjustment, the information group was less likely to report the ASC (Prevalence Ratio [PR]: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.72–0.94) and admitting privileges requirements (PR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.65–0.88) would improve safety. Participants who identified as conservative Republicans were more likely to report that the ASC (82%) and admitting privileges requirements (83%) would make abortion safer if they had heard of the provisions than if they were unaware of them (ASC: 52%; admitting privileges: 47%; all p<.001).

Conclusions

Informational statements reduced perceptions that restrictive laws make abortion safer. Voters’ prior awareness of the requirements also was associated with their beliefs.

Implications

Informational messages can shift scientifically unfounded views about abortion safety and could reduce support for restrictive laws. Because prior awareness of abortion laws does not ensure accurate knowledge about their effects on safety, it is important to reach a broad audience through early dissemination of information about new regulations.

1. Introduction

The United States (US) Supreme Court drew upon extensive scientific evidence in its June 2016 ruling that two provisions of Texas’ omnibus abortion law, House Bill 2 (HB 2), were unconstitutional because they created an undue burden on women’s access to abortion while offering no documented health and safety benefits [1,2]. However, public opinion about abortion safety is not consistent with this evidence. In several studies, reproductive-aged women overestimate the risks of abortion and often view abortion as less safe than childbirth [3,4]. Such views likely undergird some of the public’s support for requirements like those included in HB 2. Among Texas women 18–49 years old who both knew about and supported provisions of HB 2 in a 2015 survey, the most common reason given was that they believed the provisions make abortion safer [5].

Recent studies on vaccine safety suggest that it may be possible to change perceptions about health issues that are based on misinformation. In these studies, brief online informational interventions reduced misperceptions that flu and measles-mumps-rubella vaccines cause the flu and autism, respectively [6,7]. However, attitudinal change following efforts to correct misinformation about contentious issues often varies according to people’s pre-existing biases. While safety messages did not change parents’ intentions to vaccinate their child among those with favorable attitudes toward vaccines, the messages reduced intentions to vaccinate among those with the least favorable attitudes, a phenomenon referred to as a ‘backfire effect’ [6,7].

In this study, we report on results from a statewide survey of Texas voters’ views regarding the two provisions of Texas HB 2 that were challenged in the Supreme Court: requiring all abortion facilities to meet the standards of ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) and requiring physicians providing abortion care to have hospital admitting privileges within 30 miles of the facility. We compare voters’ beliefs that the two provisions would make abortion safer and their support for the two requirements according to whether they received informational statements about abortion safety, as well as their prior awareness of the requirements, political affiliation and views on abortion.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted an online survey experiment with a sample of self-identified Texas voters ages 18 and older who were members of the YouGov opt-in Internet Panel [8]. The institutional review board at the principal investigator’s university approved this study.

Given typical participation and completion rates for online surveys, YouGov invited 4,780 adult panel members in Texas to participate in the study to reach a target sample of 1,200 voters, the maximum weighted sample expected based on their previous opinion polls in Texas [9]. YouGov sent panel members up to three emails about completing the survey. Overall, 1,834 members responded to the survey invitation and answered questions about their age, home zip code and voter registration status to confirm their eligibility; this represents a 35.9% participation rate, which is similar to that of other public opinion research [6,10]. Eligible respondents provided informed consent before completing the survey and received participation points that could be redeemed for cash-equivalent rewards.

Between May and June 2016, YouGov fielded the 28-item survey in English and Spanish with eligible respondents. YouGov then matched respondents on gender, age, race, education, ideology, and political interest to a sampling frame constructed from the 2012 American Community Survey. They created survey weights for the matched respondents using characteristics of Texas voters from the November 2012 Current Population Survey and 2007 Pew Religious Life Survey [11]. This sample matching methodology produces a representative sample of the population that is more accurate than random-digit-dialing methods [11,12].

2.1. Study design

YouGov used a computer-generated simple random number sequence to randomize eligible participants to an online questionnaire that included informational statements about abortion safety or no safety information. Upon initiating the survey, participants reported their general view on the morality and legality of abortion. Following other studies [5,13], they indicated which statement about abortion came closest to their view: “I believe having an abortion is morally acceptable and should be legal;” “I am personally against abortion for myself, but I don’t believe government should prevent a woman from making that decision for herself;” or “I believe having an abortion is morally wrong and should be illegal.” They also could indicate that they held some other view. We then asked participants about whether they had heard of the ASC requirement that was recently passed in Texas, and, in a separate question, if they had heard of the hospital admitting privileges requirement.

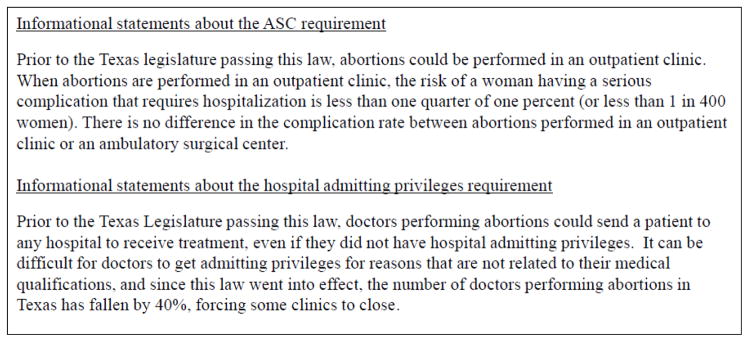

Next, the information group read a statement describing the safety of office-based abortion (Figure 1) [14,15] and then reported whether they strongly supported, somewhat supported, somewhat opposed or strongly opposed the requirement, or if they were not sure. They also reported whether they believed that the requirement would make abortion more safe, less safe, have no effect on safety, or did not know. After reading a second statement about physician practices prior to HB 2 [16], voters answered the same questions about the admitting privileges requirement. The group without safety information answered questions about their support for each requirement and its effect on safety without seeing the informational statements.

Figure 1.

Statements presented to the information group before they answered questions about their support for the ambulatory surgical center (ASC) and hospital admitting privileges requirements and whether they believed each requirement would make abortion safer

The survey also collected information on participants’ age, race and ethnicity, and educational attainment. Using a seven-point scale, participants indicated their party affiliation (from strong Democrat to strong Republican) and political ideology (from extremely liberal to extremely conservative). We averaged the values of the two variables to create a composite score, in which smaller values indicate the respondent is more conservative and a strong Republican and larger values indicating s/he is more liberal and identifies as a strong Democrat [5,17]. To facilitate interpretation, we created the following categories based on quintiles of the composite score: conservative Republican, somewhat conservative Republican, moderate or Independent, somewhat liberal Democrat, and liberal Democrat.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Our primary outcome was the difference in voters’ beliefs that the ASC and admitting privileges requirements would make abortion safer. We compared the distribution of characteristics for the information group and group without information and the percentage that had heard of the two provisions and believed that they would make abortion safer, using chi-squared tests. We then assessed the association between group assignment and reporting that each requirement would improve abortion safety, using multivariable-adjusted Poisson regression models with robust standard errors [18] that controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education.

In a second set of models, we assessed the association between prior awareness of the requirement and beliefs that the requirement would make abortion safer. We included an interaction between prior awareness and group assignment because those who had heard of the requirement may have pre-existing biases about the impact on safety, which may modify the effect of the informational statements [6,7]. These biases likely stem from the sources to which people turn for information, which are often aligned with their ideological views [19]. Therefore, we also included an interaction between awareness of the requirement and respondents’ party affiliation/ideology and, separately, their personal views on abortion. We determined the significance of the interaction terms using the Wald test. To facilitate the interpretation of these terms, we estimated predicted probabilities of reporting that the provisions would improve abortion safety for demographic subgroups, according to awareness of the provisions.

We followed the same approach to assess the effect of the informational statements on our secondary outcome: support for the ASC and admitting privileges requirements. We conducted all analyses in Stata 13 and used the probability weights provided by YouGov.

3. Results

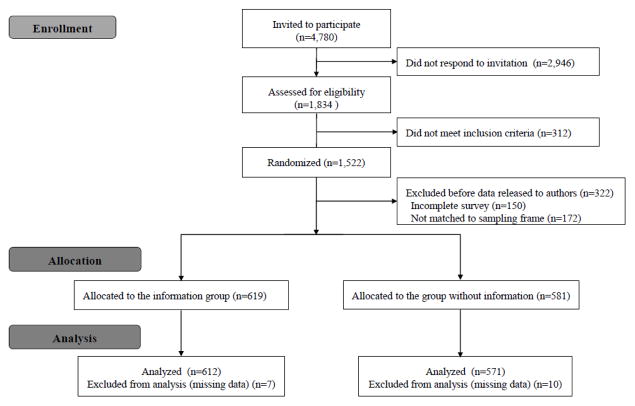

Of 1,522 eligible respondents who initiated the survey, 1,372 completed it (90.3% completion rate) and YouGov matched 1,200 to the sampling frame (Figure 2). After excluding those missing information on awareness of or opinions about the ASC or admitting privileges requirements (n=17), the final sample included 1,183 respondents: 612 completed the survey with informational statements and 571 completed the survey without safety information. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics or awareness of the provisions between the two groups (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Participant eligibility and group allocation

The information group read a statement describing the safety of office-based abortion prior to the passage of Texas House Bill 2 (HB 2) before answering questions about the ASC requirement. They also read a second statement describing physician practices before HB 2, as well as the law’s impact on the number of abortion providers after its passage, before answering questions about the admitting privileges requirement. The group without information did not see these statements before answering the same questions about the two requirements

Table 1.

Characteristics of Texas voters surveyed about their opinions of abortion laws (n=1,183)

| Group without information | Information groupa | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=571 | n=612 | ||

| Age, years | |||

| 18 – 29 | 94 (18.3) | 91 (12.5) | |

| 30 – 45 | 162 (30.0) | 169 (29.0) | 0.11 |

| 46 – 64 | 210 (34.1) | 234 (37.4) | |

| ≥65 | 105 (17.7) | 118 (21.1) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 314 (52.4) | 349 (57.4) | 0.15 |

| Male | 257 (47.6) | 263 (42.5) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 351 (58.2) | 374 (61.1) | |

| Black | 66 (10.6) | 80 (12.6) | 0.36 |

| Hispanic | 129 (27.1) | 136 (23.7) | |

| Other/multi-racial | 25 (4.1) | 22 (2.5) | |

| Educational attainment | |||

| High school or less | 163 (31.4) | 195 (33.7) | |

| Some college/2-year degree | 234 (39.0) | 231 (34.2) | 0.34 |

| College degree or more | 174 (29.5) | 186 (32.1) | |

| Party affiliation & ideology | |||

| Conservative Republican | 121 (25.4) | 127 (26.2) | |

| Somewhat conservative Republican | 93 (17.6) | 117 (21.0) | |

| Moderate/Independent | 116 (23.1) | 137 (20.8) | 0.18 |

| Somewhat liberal Democrat | 104 (17.2) | 118 (20.3) | |

| Liberal Democrat | 137 (16.6) | 113 (11.7) | |

| Personal views of abortion | |||

| Abortion is morally acceptable, and should be legal | 166 (24.6) | 161 (23.1) | |

| Personally against abortion, but the government should not prevent others from making this decision | 229 (39.8) | 233 (37.5) | 0.74 |

| Abortion is morally wrong, and should be illegal | 132 (28.1) | 164 (31.2) | |

| Other view | 44 (7.5) | 54 (8.1) | |

| Awareness of ASC law | |||

| Aware | 353 (58.5) | 365 (57.6) | 0.81 |

| Unaware/Not sure | 218 (41.5) | 247 (42.4) | |

| Awareness of admitting privileges law | |||

| Aware | 280 (47.7) | 288 (45.4) | 0.53 |

| Unaware/Not sure | 291 (52.3) | 324 (54.5) | |

All data are presented as n (%). ASC: Ambulatory surgical center

The information group read a statement describing the safety of office-based abortion prior to the passage of Texas House Bill 2 (HB 2) before answering questions about the ASC requirement. They also read a second statement describing physician practices before HB 2, as well as the law’s impact on the number of abortion providers after its passage, before answering questions about the admitting privileges requirement. The group without information did not see these statements before answering the same questions about the two requirements.

Differences between the information group and group without information were assessed using chi-squared tests.

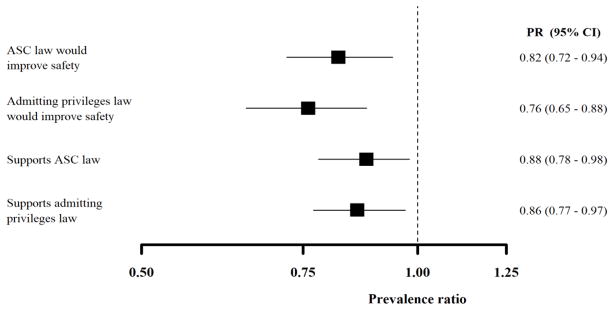

Overall, 259 (46%) in the information group and 298 (56%) in the group without information believed the ASC provision would improve abortion safety (p=.008); 230 (41%) in the information group and 285 (54%) in the group without information also believed the admitting privileges provision would make abortion safer (p<.001). After multivariable adjustment, respondents in the information group were less likely to report that the ASC (PR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.72–0.94) and admitting privileges requirements (PR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.65–0.88) would improve abortion safety (Figure 3). Prior awareness of the provisions did not modify the association between group assignment and perceptions that the two provisions would improve safety, except in the model for the admitting privileges requirement that controlled for views on abortion (Wald test p-value=.01; Table A.1).

Figure 3.

Effect of the informational statements on perceptions of safety and support for the ambulatory surgical center (ASC) and hospital admitting privileges requirementsa

PR: Prevalence ratio from Poisson regression model that adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity and education; CI: confidence interval.

a. The information group read a statement describing the safety of office-based abortion prior to the passage of Texas House Bill 2 (HB 2) before answering questions about the ASC requirement. They also read a second statement describing physician practices before HB 2, as well as the law’s impact on the number of abortion providers after its passage before answering questions about the admitting privileges requirement. The group without information did not see these statements before answering the same questions about the two requirements.

In all models, participants’ political affiliation/ideology and views on abortion modified the association between awareness of the requirement and perceptions that the provision would improve safety (Table 2). Participants with more conservative political views and who believe abortion is morally wrong and should be illegal were more likely to report that each requirement would make abortion safer if they had heard of the laws than if they were unaware of them (Wald test p-value <.001). For example, 83% of participants who identified as conservative Republicans who had heard of the admitting privileges requirement reported that it would make abortion safer, compared to 47% who were unaware of the requirement. Among those with more liberal political views and who believe abortion is morally acceptable and should be legal, respondents who had heard of the provisions were less likely to believe that the requirements would make abortion safer than those who were unaware of the provisions.

Table 2.

Predicted probability of reporting that the ambulatory surgical center (ASC) and hospital admitting privileges requirements would improve abortion safety, by awareness of the laws, party affiliation/ideology and views of abortion

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaware of lawc | Aware of law | Unaware of lawc | Aware of law | |

| Panel 1: ASC would improve abortion safety | ||||

| Party affiliation & ideology | ||||

| Conservative Republican | 52.3 | 81.9*** | -- | -- |

| Somewhat conservative Republican | 52.0 | 78.3 | -- | -- |

| Moderate/Independent | 43.8 | 52.0 | -- | -- |

| Somewhat liberal Democrat | 35.8 | 23.9 | -- | -- |

| Liberal Democrat | 41.6 | 16.7 | -- | -- |

| Personal views of abortion | ||||

| Abortion is morally acceptable, and should be legal | -- | -- | 48.4 | 27.6*** |

| Personally against abortion, but the government should not prevent others from making this decision | -- | -- | 52.2 | 48.3 |

| Abortion is morally wrong, and should be illegal | -- | -- | 32.0 | 80.4 |

| Panel 2: Admitting privileges would improve abortion safety | ||||

| Party affiliation & ideology | ||||

| Conservative Republican | 46.6 | 83.3*** | -- | -- |

| Somewhat conservative Republican | 51.6 | 76.8 | -- | -- |

| Moderate/Independent | 43.9 | 43.3 | -- | -- |

| Somewhat liberal Democrat | 37.3 | 28.8 | -- | -- |

| Liberal Democrat | 27.2 | 10.8 | -- | -- |

| Personal views of abortion | ||||

| Abortion is morally acceptable, and should be legal | -- | -- | 36.7 | 21.8*** |

| Personally against abortion, but the government should not prevent others from making this decision | -- | -- | 50.4 | 47.7 |

| Abortion is morally wrong, and should be illegal | -- | -- | 38.2 | 78.7 |

Wald test p-value <.05;

Wald test p-value <.001

Probabilities estimated from Poisson regression models that included information group*awareness of the law, party affiliation/ideology*awareness of the law, age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity. The information group read a statement describing the safety of office-based abortion prior to the passage of Texas House Bill 2 (HB 2) before answering questions about the ASC requirement. They also read a second statement describing physician practices before HB 2, as well as the law’s impact on the number of abortion providers after its passage, before answering questions about the admitting privileges requirement. The group without information did not see these statements before answering the same questions about the two requirements.

Probabilities estimated from Poisson regression models that included information group*awareness of the law, views on abortion* awareness of the law, age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity.

Includes voters who said they were not sure if they had heard of the law before.

In the information group, 308 respondents (54%) supported the ASC and 298 (54%) supported the admitting privileges requirements, compared with 331 (62%) and 340 (63%) in the group without information, respectively (ASC p=.04; admitting privileges p=.02). After multivariable adjustment, the information group was less likely to support the ASC (PR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.78–0.98) and admitting privileges requirements (PR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.77–0.97; Figure 3). Awareness of the ASC and admitting privileges requirements did not modify the association between group assignment and support for the two provisions, but did modify the association between party affiliation/ideology, views on abortion and support (Table A.2 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Predicted probability of supporting the ambulatory surgical center (ASC) and hospital admitting privileges requirements, by awareness of the laws, party affiliation/ideology and views of abortion

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaware of lawc | Aware of law | Unaware of lawc | Aware of law | |

| Panel 1: ASC would improve abortion safety | ||||

| Party affiliation & ideology | ||||

| Conservative Republican | 57.5 | 94.8*** | -- | -- |

| Somewhat conservative Republican | 64.7 | 84.1 | -- | -- |

| Moderate/Independent | 50.7 | 55.9 | -- | -- |

| Somewhat liberal Democrat | 41.8 | 33.5 | -- | -- |

| Liberal Democrat | 55.5 | 20.5 | -- | -- |

| Personal views of abortion | ||||

| Abortion is morally acceptable, and should be legal | -- | -- | 50.7 | 27.8*** |

| Personally against abortion, but the government should not prevent others from making this decision | -- | -- | 62.8 | 55.1 |

| Abortion is morally wrong, and should be illegal | -- | -- | 42.6 | 94.8 |

| Panel 2: Admitting privileges would improve abortion safety | ||||

| Party affiliation & ideology | ||||

| Conservative Republican | 63.1 | 98.5*** | -- | -- |

| Somewhat conservative Republican | 62.7 | 88.9 | -- | -- |

| Moderate/Independent | 51.5 | 58.2 | -- | -- |

| Somewhat liberal Democrat | 45.4 | 28.2 | -- | -- |

| Liberal Democrat | 48.2 | 21.4 | -- | -- |

| Personal views of abortion | ||||

| Abortion is morally acceptable, and should be legal | -- | -- | 43.2 | 28.3*** |

| Personally against abortion, but the government should not prevent others from making this decision | -- | -- | 62.7 | 58.9 |

| Abortion is morally wrong, and should be illegal | -- | -- | 55.1 | 92.8 |

Wald test p-value <.001

Probabilities estimated from Poisson regression models that included information group*awareness of the law, party affiliation/ideology*awareness of the law, age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity. The information group read a statement describing the safety of office-based abortion prior to the passage of Texas House Bill 2 (HB 2) before answering questions about the ASC requirement. They also read a second statement describing physician practices before HB 2, as well as the law’s impact on the number of abortion providers after its passage, before answering questions about the admitting privileges requirement. The group without information did not see these statements before answering the same questions about the two requirements.

Probabilities estimated from Poisson regression models that included information group*awareness of the law, views on abortion* awareness of the law, age, gender, education, and race/ethnicity.

Includes voters who said they were not sure if they had heard of the law before.

4. Discussion

There is a substantial gap between the scientific evidence demonstrating the safety of abortion in the US and public opinion about abortion safety [3–5]. In the present study, approximately half of registered Texas voters believed that the ASC and admitting privileges requirements would make abortion safer and a similar percentage supported these provisions. Our results indicate, however, that messages aimed at correcting misinformation about the medical necessity of these requirements significantly reduced perceptions that these measures would make abortion safer, as well as reduced support for the requirements. These findings correspond, in part, to those reported in recent studies on interventions to correct misinformation about vaccine safety [6,7], and suggest that it may be possible to shift misperceptions about the risks of abortion and bring public opinion more in line with scientific evidence.

However, unlike the vaccine safety studies [6,7], the association between prior awareness of the requirement did not modify the association between group assignment and perceived safety, with the exception of the model for the safety of admitting privileges provision that included voters’ views on abortion. But in this case, we did not observe a ‘backfire effect’ demonstrating increased support for abortion restrictions; instead, our results indicate that some participants maintained their position on abortion laws. This may be due to the fact that the information presented did not threaten their views on abortion, which might trigger a response opposite of what was intended [6,7]. Our results, therefore, suggest that messages about abortion safety and the impact of restrictive laws may be effective at changing misperceptions among the majority of voters.

Another central finding, unrelated to the informational statements, was that the beliefs about safety were more prevalent among voters in political and attitudinal subgroups who are traditionally considered opponents of abortion that previously had heard of the requirements than members of these same groups who were unaware of the provisions. A similar but opposite effect was observed among traditional supporters of abortion rights, such as participants who identified as liberal Democrats and those who think abortion should be legal. This suggests that voters who have heard of the provisions have assimilated targeted messaging about them.

While safety may play a somewhat lesser role in framing new restrictions on abortion, the results from this study point to the importance of broadly disseminating corrective narratives that counter any misinformation about abortion care and call attention to anticipated adverse effects on access. A challenge is that agencies typically charged with communicating information about public health issues, like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, are no longer actively engaged in this work [20], or have become aides of misinformation by publishing scientifically inaccurate materials about abortion and its risks, as in the case of some state health departments [21]. The National Academy of Medicine’s consensus study on abortion marks a recent shift [22]. However, absent support from government agencies, other entities could partner with community-based organizations to develop and disseminate accurate information about abortion through community forums or online materials, such as the University of California, San Francisco’s Explained: Abortion Research and Policy series [23].

Similar to other studies on interventions aimed at opinion change, our study has limitations. Of YouGov panelists who were invited to take part in the study, 36% responded to the email invitation. This participation rate is similar to other online panel studies and is not considered equivalent to the response rate in which probability sampling is used [6,24]. Moreover, use of sample matching and weights, as in this study, considerably reduces any bias from an opt-in panel sample [11,12]. Additionally, we did not have data about the sources from which respondents learned about the HB 2 requirements and, instead, used a proxy (i.e., an interaction between prior awareness of the law and demographic characteristics) for pre-existing biases respondents may have held. Finally, the informational statements we developed were brief and may not have been sufficiently informative or persuasive for some respondents and may not have a lasting effect on others’ beliefs. Future research should identify voters’ central sources of information about abortion regulations and assess the extent to which these could be used to disseminate persuasive evidence on abortion safety.

Despite these limitations, our study indicates that it may be possible to change perceptions about abortion that underlie support for restrictions if these perceptions are based on incomplete or inaccurate information. They also point to the opportunity that abortion rights advocates have to ensure that voters who are generally supportive of women’s access to abortion have better information about the safety of abortion and the potential impact that further restrictions would have on access to care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding source: This project was supported by a grant from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation and a center grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5 R24 HD042849) awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. These funders played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Whole Woman’s Health v Hellerstedt. 579 U.S.___________ (2016). No. 15–274. Supreme Court of the United States. (June 27, 2016). Supreme Court of the United States Blog. http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/whole-womans-health-v-cole/. [accessed July 28, 2016].

- 2.Grossman D. The use of public health evidence in Whole Woman’s Health v Hellerstedt. JAMA Int Med. 2017;177(2):155–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavanaugh ML, Bessett D, Littman LL, Norris A. Connecting knowledge about abortion and sexual and reproductive health to belief about abortion restrictions: Findings from an online survey. Women’s Health Issues. 2013;23–24:e239–e47. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiebe ER, Littman LL, Kaczorowski J. Knowledge and attitudes about contraception and abortion in Canada, US, UK, France and Australia. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale) 2015;5(9):322. [Google Scholar]

- 5.White K, Potter JE, Stevenson AJ, Fuentes L, Hopkins K, Grossman D. Women’s knowledge of and support for abortion restrictions in Texas: Findings from a statewide representative survey. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48(4):189–97. doi: 10.1363/48e8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyhan B, Reifler J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effect of corrective information. Vaccine. 2015;33:459–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey SB, Freed GL. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: A randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):1–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.YouGov. [accessed October 30, 2016];About YouGov. 2016 https://today.yougov.com/about/about/

- 9.The Texas Politics Project. University of Texas/Texas; Tribune Poll: Feb, 2016. [accessed April 7, 2017]. https://texaspolitics.utexas.edu/polling-data-archive. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almeling R, Gadarian SK. Public opinion on policy issues in genetics and genomics. Genetics in Medicine. 2014;16:491–4. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivers D. [accessed November 16, 2016];Pew research: YouGov consistently outperforms competitors on accuracy. 2016 https://today.yougov.com/news/2016/05/13/pew-research-yougov/

- 12.Vavreck L, Rivers D. The 2006 cooperative congressional election study. J Elections Public Opin Parties. 2008;18(4):355–66. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research. NARAL Pro-Choice America: National survey. Washington, D.C: Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upadhyay UD, Desai S, Zlidar V, Weitz T, Grossman D, Anderson P, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits and complications after abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):175–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White K, Carroll E, Grossman D. Complications from first-trimester aspiration abortion: A systematic review of the literature. Contraception. 2015;92(5):422–38. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Texas Policy Evaluation Project. [accessed August 19, 2017];Change in number of physicians providing abortion care in Texas after HB2. 2016 https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/txpep/_files/pdf/TxPEP-ResearchBrief-AdmittingPrivileges.pdf.

- 17.Johnston CD, Hillygus DS, Bartels BL. Ideology, the Affordable Care Act ruling and Supreme Court legitimacy. Public Opin Q. 2014;78(4):963–73. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pew Research Center. [accessed November 16, 2016];Political polarization and media habits: From Fox news to Facebook, how liberals and conservatives keep up with politics. 2014 http://journalism.org/2014/10/21/political-polarization-media-habits/

- 20.Cates W, Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Abortion surveillance at CDC: Creating public health light out of political heat. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(1) Supplement 1:12–7. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniels CR, Ferguson J, Howard G, Roberti A. Informed or misinformed consent? Abortion policy in the United States. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2013;41(2):181–209. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3476105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. [accessed April 4, 2017];Reproductive health services: Assessing the safety and quality of abortion care. 2017 http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Women/ReproductiveHealthServices.aspx.

- 23.Innovating Education in Reproductive Health. [accessed March 10, 2017];Explained: Abortion research & policy. 2015 http://innovating-education.org/course/explained-abortion-research-policy-2/

- 24.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.