Abstract

Background

The focus of healthcare reform is shifting from all-cause to potentially preventable readmissions. Potentially preventable within stay readmission rates is a measure recently adopted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Quality Reporting Program.

Objective

We examined the patient-level predictors of potentially preventable within stay readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries receiving care in inpatient rehabilitation facilities. We also studied the reasons for readmissions and the risk-standardized variation across states.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Inpatient rehabilitation facilities.

Patients

Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries receiving inpatient rehabilitation following hospitalization in 2012–2013 (N=345,697).

Methods

Medicare claims were reviewed to identify potentially preventable readmissions occurring during inpatient rehabilitation.

Main Outcome Measures

1) Observed rates and odds of potentially preventable within stay readmissions by patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, 2) risk-standardized state rates, and 3) primary diagnoses for hospital readmissions.

Results

The overall rate of potentially preventable within stay readmissions was 3.5% (n=11,945). Older age, male sex, hospitalizations over the prior six months, longer hospital lengths of stay, ICU utilization, and number of comorbidities were associated with increased odds. Dual eligibility and disability status were not associated with increased odds. Higher functional scores at rehabilitation admission were associated with lower odds. Rates and odds varied across rehabilitation impairment groups. Risk-standardized state rates ranged from 3.1% to 4.1%. Readmissions for conditions reflecting inadequate management of infections (36.8%) were the most frequent and readmissions for inadequate injury prevention (6.1%) least frequent.

Conclusions

Potentially preventable within stay readmissions may represent a target for inpatient rehabilitation care improvement. Our findings highlight the need for care coordination across providers. Future research should focus on care processes that reduce patients’ risk of these potentially preventable rehospitalizations.

Introduction

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 established the Center for Medicare and Medicaid’s (CMS) Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Quality Reporting Program.1 The program requires the public reporting of selected quality measures to enhance transparency and enable informed decision-making among patients and caregivers.2,3 A measure recently adopted for the Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Quality Reporting Program is potentially preventable within stay readmission rates.4 “Within stay” readmissions include temporary transfers (rehabilitation program interruptions) and discharges to acute care.5

There are two important distinctions between potentially preventable within stay readmissions and the readmissions that have been the focus of recent research:6–8 timing (during care or ending care early rather than post-discharge) and the medical issue leading to the readmission (potentially preventable rather than all-cause or unplanned). A list of potentially preventable diagnoses has been developed for the within stay readmission metric.5,9 These diagnoses are considered potentially avoidable with appropriate healthcare interventions and are classified into five descriptive groupings: 1) inadequate management of chronic conditions, 2) inadequate management of infections, 3) inadequate management of unplanned events, 4) inadequate prophylaxis, and 5) inadequate injury prevention.5 Ideally, patients under the care of an inpatient rehabilitation facility should not require readmission to a hospital for the identified diagnoses. Because these readmissions are “within stay” and “potentially preventable”, they may be more reflective of patient safety and quality of care than post-discharge readmissions. Improving patient safety and quality of care are national priorities.10,11

Most studies examining readmissions among inpatient rehabilitation patients have focused on post-discharge readmissions. The objective of our study was to examine the patient-level predictors of potentially preventable within stay readmissions among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries receiving care in inpatient rehabilitation facilities. This is an important area of research as the focus of healthcare reform is shifting from all-cause to potentially preventable readmissions.5,12,13 Our findings provide insight into who is at increased risk, an important first step in identifying patient safety concerns and improving care through prevention efforts. We also examined the medical diagnoses leading to these potentially preventable readmissions and the geographic variation in rates. Findings could inform providers and policy-makers targeting care improvement opportunities.

Methods

Data Sources

The following 100% Medicare files from 2012–2013 were used to address the study objective: Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI), Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR), and Beneficiary Summary. IRF-PAI files contain assessment data related to inpatient rehabilitation stays and are submitted to the CMS to determine payment under the fee-for-service prospective payment system.14 We used IRF-PAI files to extract information on primary rehabilitation condition and functional status. MedPAR files contain final claims for all Medicare fee-for-service inpatient stays, including those in acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities, and psychiatric hospitals.15 We used MedPAR files to extract information on hospitalizations prior to and during inpatient rehabilitation. Finally, Beneficiary Summary files were used to extract patient sociodemographic information.16 Files were linked using encrypted unique beneficiary identification numbers. The study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board; CMS data were obtained after we established a Data Use Agreement.

Study Cohort

The population of interest was Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries admitted to inpatient rehabilitation following hospitalization. An initial cohort was selected by identifying inpatient rehabilitation admissions occurring between August 1, 2012 and November 15, 2013 in the IRF-PAI files. The start of this window allowed a six-month look back, including patients with hospital lengths of stay of 30 days. The end of the window allowed observation of potentially preventable readmissions, even for those with rehabilitation lengths of stays of 45 days. The constraints placed on hospital (≤30 days) and rehabilitation (3–45 days) lengths of stay were based on clinical judgement and observational analyses of the data. Our goal was to ensure the cohort was representative of typical patients, not those experiencing excessively long hospitalizations or rehabilitation stays due to factors not captured in administrative data.

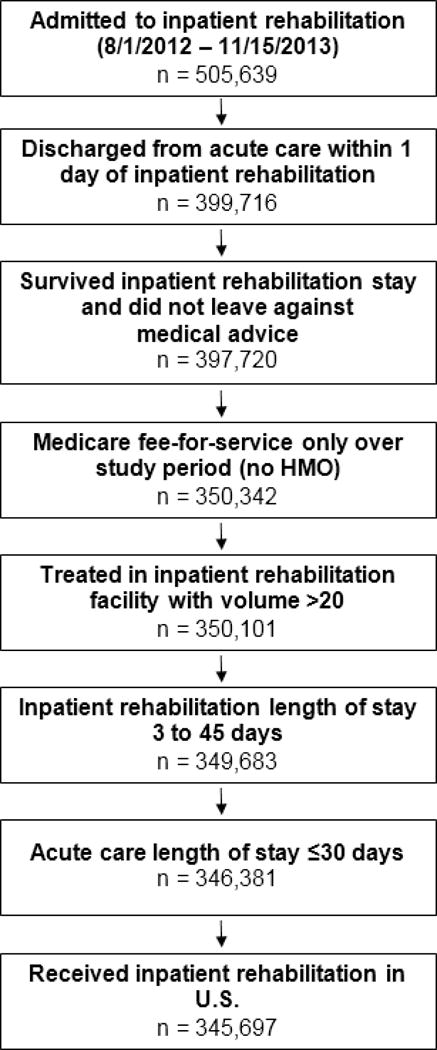

Inpatient rehabilitation stays of three days or less are considered a “short-stay” by CMS, with their own payment category.3 As with long stays, short stays may not be representative typical patients and were removed from the cohort. We also excluded patients treated in inpatient rehabilitation facilities with 20 or fewer admissions over the study period and those outside the United States, as care processes, and subsequently outcomes, may be different in these facilities. Detailed cohort selection is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart presenting number of eligible cases remaining at each step as exclusion criteria applied.

Variables

Outcome variable

The outcome of interest was potentially preventable readmissions occurring during inpatient rehabilitation. We reviewed all MedPAR claims for included beneficiaries. In accordance with the specifications of the CMS potentially preventable metric, hospital admissions occurring during an inpatient rehabilitation stay, the day of discharge, or the day following discharge were considered readmissions.5 To identify our outcome of interest, we first identified all readmissions, and then we determined whether or not the readmission was for a condition considered potentially preventable by comparing the acute care hospital diagnosis (ICD-9) codes to the list developed for the potentially preventable within stay measure.5 The conceptual definition for “potentially preventable” readmissions used by measure developers is as follows: “For the within-PAC [postacute care] stay window, potentially preventable readmissions should be avoidable with sufficient medical monitoring and appropriate patient treatment.”5, p5 Measure developers created the list of diagnoses considered potentially preventable based on this conceptual definition using an environmental scan, input from a technical expert panel, and clinical expertise. The developers grouped the potentially preventable diagnoses into the following categories based on the clinical reason for considering the condition “potentially preventable”: inadequate management of chronic conditions, inadequate management of infections, inadequate management of unplanned events, inadequate prophylaxis, or inadequate injury.5 We categorized potentially preventable readmissions into these groups using the specifications for the potentially preventable within stay metric.5 Patients with readmissions for diagnoses other than those specified as potentially preventable remained in the cohort; however, they were not considered to have the outcome of interest.

Sociodemographic variables

Patients’ age, sex, race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic white, Non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Other), Medicare disability entitlement (disability original reason for Medicare enrollment, yes/no), and dual eligibility (Medicare and Medicaid eligible, yes/no) were extracted from the Beneficiary Summary files.

Clinical variables

We reviewed MedPAR claims for the hospitalization immediately preceding inpatient rehabilitation (index hospitalization) to extract primary diagnosis, comorbidities, length of stay (days), and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) utilization (yes/no). We grouped hospital primary diagnoses into Clinical Classification Software (CCS) multi-level diagnostic categories.17 These diagnostic categories were developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project to group ICD-9 codes into clinically meaningful categories.17 We identified patient comorbidities from hospital discharge ICD-9 codes using the Elixhauser comorbidity measure. The Elixhauser approach was developed for use with administrative datasets and identifies 31 comorbidities, defined as diagnoses secondary to the admitting diagnosis that may impact healthcare utilization and/or mortality.18 We also used MedPAR claims data to determine the number of hospital admissions (count) the patient had over the six months prior to their index hospitalization.

We extracted clinical information from IRF-PAI records, including reason for rehabilitation (admitting diagnosis) and functional status at admission. We collapsed inpatient rehabilitation admitting diagnoses into 10 impairment groups for reporting.19 These impairment groupings were developed by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and are used for reporting to Congress.19 Functional status is assessed at inpatient rehabilitation admission and discharge using 18 data elements from the Functional Independence Measure (FIM), which are included in the IRF-PAI.20 These items are rated on a 7-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater independence. We grouped the 18 items into self-care, bowel/bladder management, mobility, and cognition domains. The self-care domain included six items related to eating, grooming, bathing, dressing-upper body, dressing-lower body, and toileting (score range 6–42). Bowel/bladder management included two items related to bowel management and bladder management (score range 2–14). The mobility domain included five items related to transfers, walking/wheelchair mobility, and ability to climb stairs (score range 5–35). The cognition domain included the remaining five items related to comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem solving, and memory (score range 5–35).14

Data analysis

To examine patient-level predictors of potentially preventable within stay readmissions, we calculated 1) observed rates by patient characteristics and 2) odds ratios from a multilevel logistic regression model. Multilevel modelling accounted for the clustering of patients within inpatient rehabilitation facilities. The multilevel model estimating the dichotomous outcome (potentially preventable readmission, yes/no) was adjusted for the following patient-level covariates: age, sex, race/ethnicity, dual eligibility, disability entitlement, number of comorbidities, number of hospitalizations over the prior six months, index hospitalization length of stay, ICU utilization during index hospitalization, index hospitalization diagnostic category, inpatient rehabilitation impairment group, and functional status at admission to inpatient rehabilitation. We examined geographic variation in potentially preventable readmission rates by calculating risk-standardized rates by state. Risk-standardized rates are the ratio of the predicted number of potentially preventable readmissions to the expected number of readmissions multiplied by the national rate.5 Predicted values included the “state-effect” and were estimated from a multilevel model adjusted for the following sociodemographic and clinical covariates: age; sex; race/ethnicity; dual eligibility; disability entitlement; number of comorbidities; number of hospitalizations over the prior six months; index hospitalization primary diagnosis, length of stay, and ICU utilization; inpatient rehabilitation impairment group; and self-care, bowel/bladder management, mobility, and cognition scores at admission to inpatient rehabilitation. Expected values did not include the state-effect and were estimated from a logistic model adjusted for the same covariates. Risk-standardized rates of potentially preventable within stay readmissions higher than the national average indicate the rates in those states are “worse” than would be expected given the patient-mix in the state, whereas rates lower than the national average indicate the rates are “better” than would be expected given the patient-mix in the state. We categorized continuous variables (hospital length of stay, self-care score, bowel/bladder management score, mobility score, and cognition score) into three-levels (lowest quartile, combined middle two quartiles, and highest quartile). Analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS 23, Armonk, NY and SAS version 9.4, Cary, NC.

Results

Sample characteristics

The final sample included 345,697 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries (Figure 1). Average age was 76.1 (SD, 10.8) years. A majority of patients were female (58.6%) and non-Hispanic white (81.5%). Refer to Table 1 for further information on sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Potentially preventable within stay readmissions during inpatient rehabilitation

| Overall Sample n=345,697 | Observed Rate | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 11,945 | 3.5% | |

| Age, years | |||

| <65 | 36,817 | 2.9% | Ref |

| 65–84 | 227,615 | 3.3% | 1.18 (1.09, 1.28) |

| >84 | 81,265 | 4.0% | 1.39 (1.27, 1.53) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 202,751 | 3.0% | Ref |

| Male | 142,946 | 4.0% | 1.19 (1.14, 1.23) |

| Race/ethnicityb | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 281,624 | 3.5% | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic black | 35,795 | 3.6% | 0.95 (0.89, 1.02) |

| Hispanic | 18,382 | 3.5% | 0.89 (0.81, 0.97) |

| Other | 9,000 | 3.1% | 0.89 (0.78, 1.01) |

| Disability entitlementc | |||

| No | 267,415 | 3.5% | Ref |

| Yes | 78,282 | 3.4% | 0.98 (0.92, 1.03) |

| Dual eligibilityd | |||

| No | 279,629 | 3.4% | Ref |

| Yes | 66,068 | 3.6% | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) |

| Prior hospitalizations | |||

| 0 | 243,069 | 2.8% | Ref |

| 1 | 67,758 | 4.3% | 1.24 (1.18, 1.29) |

| 2 | 21,933 | 5.8% | 1.54 (1.44, 1.64) |

| 3+ | 12,937 | 7.4% | 1.89 (1.76, 2.04) |

| CCS Diagnostic categorye | |||

| Diseases of the Musculoskeletal System and Connective Tissue | 66,032 | 1.4% | Ref |

| Diseases of the Circulatory System | 101,097 | 4.0% | 1.39 (1.26, 1.54) |

| Injury and Poisoning | 87,240 | 3.0% | 1.34 (1.22, 1.47) |

| Diseases of the Respiratory System | 16,597 | 6.2% | 1.83 (1.64, 2.04) |

| Infectious and Parasitic Diseases | 12,389 | 6.2% | 1.57 (1.40, 1.77) |

| Diseases of the Genitourinary System | 10,157 | 4.8% | 1.39 (1.23, 1.58) |

| Diseases of the Digestive System | 11,347 | 4.5% | 1.26 (1.11, 1.43) |

| Neoplasms | 10,183 | 4.5% | 1.37 (1.21, 1.56) |

| Endocrine, Nutritional, and Metabolic | 8,233 | 4.2% | 1.31 (1.14, 1.51) |

| Diseases and Immunity Disorders | |||

| Diseases of Nervous System and Sense Organs | 12,111 | 2.5% | 0.87 (0.76, 1.01) |

| Diseases of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue | 2,321 | 4.7% | 1.46 (1.18, 1.80) |

| Disease of Blood and Blood-Forming Organs | 1,247 | 5.7% | 1.70 (1.31, 2.20) |

| Mental Disorders | 950 | 2.7% | 0.91 (0.61, 1.36) |

| Congenital Anomalies | 864 | 1.3% | 0.68 (0.37, 1.24) |

| Other | 4,929 | 3.4% | 1.05 (0.88, 1.26) |

| Hospital LOS | |||

| <4 days | 106,953 | 1.8% | Ref |

| 4 to 7 days | 147,141 | 3.2% | 1.24 (1.17, 1.31) |

| >7 days | 91,603 | 5.7% | 1.59 (1.50, 1.69) |

| ICU | |||

| No | 214,893 | 2.8% | Ref |

| Yes | 130,804 | 4.6% | 1.12 (1.07, 1.17) |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Sum | |||

| 0–1 | 35,836 | 1.5% | Ref |

| 2–4 | 177,881 | 2.6% | 1.20 (1.10, 1.31) |

| 5+ | 131,980 | 5.2% | 1.75 (1.60, 1.92) |

| IR Impairment group | |||

| LE Fracture | 48,190 | 2.5% | Ref |

| Stroke | 70,080 | 3.3% | 1.12 (1.02, 1.24) |

| LE Joint Replacement | 39,945 | 0.9% | 0.84 (0.73, 0.96) |

| Neurologic Disorders | 35,281 | 4.8% | 1.59 (1.4 5, 1.75) |

| Debility | 32,947 | 4.5% | 1.51 (1.37, 1.67) |

| Brain Injury | 26,987 | 4.6% | 1.58 (1.43, 1.73) |

| Other Ortho Conditions | 22,695 | 2.3% | 1.23 (1.10, 1.37) |

| Cardiac Conditions | 20,332 | 6.0% | 1.97 (1.77, 2.19) |

| Spinal Cord Injury | 15,626 | 3.1% | 1.51 (1.34, 1.71) |

| Other | 33,614 | 4.3% | 1.46 (1.33, 1.60) |

| Self-care at IR admissionf | |||

| <16 points | 91,847 | 5.7% | Ref |

| 16–24 points | 178,825 | 3.0% | 0.76 (0.72, 0.80) |

| >24 points | 75,025 | 1.7% | 0.57 (0.53, 0.62) |

| Bowel/Bladder Management at IR admissionf | |||

| <4 points | 79,437 | 5.6% | Ref |

| 4–10 points | 187,921 | 3.1% | 0.85 (0.81, 0.89) |

| >10 points | 78,339 | 2.1% | 0.73 (0.68, 0.78) |

| Mobility at IR admissionf | |||

| <7 points | 71,611 | 5.8% | Ref |

| 7–13 points | 192,691 | 3.3% | 0.75 (0.71, 0.78) |

| >13 points | 81,395 | 1.8% | 0.51 (0.47, 0.55) |

| Cognition at IR admissionf | |||

| <19 points | 86,526 | 4.9% | Ref |

| 19–27 points | 155,754 | 3.4% | 0.94 (0.90, 0.99) |

| >27 points | 103,417 | 2.3% | 0.86 (0.81, 0.92) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CCS, Clinical Classification Software; LOS, length of stay; ICU, intensive care unit; IR, inpatient rehabilitation; LE, lower extremity; Ortho, orthopedic

Odds ratios are adjusted for all variables presented in the table.

Race/ethnicity missing for 896 cases in the overall sample and 18 cases with potentially preventable within stay readmissions.

“Disability” original reason for receiving Medicare.

Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) 2015. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/CCSUsersGuide.pdf. Accessed 5/16/2016.

Functional domains are derived from the items in the Functional Independence Measure. Self-care: 6 items related to eating, grooming, bathing, dressing-upper body, dressing-lower body, and toileting (score range 6–42); Bowel/Bladder Management: 2 items related to bladder management and bowel management (score range 2–14); mobility: 5 items related to transfers, walking/wheelchair mobility, and ability to climb stairs (score range 5–35); cognition: 5 items related to comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem solving, and memory (score range 5–35).

Potentially preventable within stay readmissions

Observed rates of potentially preventable within stay readmissions and adjusted odds ratios are presented in Table 1. The national rate of potentially preventable within stay readmissions was 3.5%. Of the 11,945 potentially preventable readmissions, most were discharges to acute care; only 6.3 % (N=751) were temporary transfers (rehabilitation program interruptions).

The sociodemographic characteristics associated with higher odds of a potentially preventable readmission were older age (OR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.09–1.28 for 65 to 84 years; OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.27–1.53 for >84 years, compared to <65 years) and male sex (OR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.14–1.23). Neither dual eligibility nor disability entitlement were associated with increased odds of a potentially preventable within stay readmission.

The clinical characteristics associated with higher odds of a potentially preventable within stay readmission were number of prior hospitalizations (OR: 1.89, 95% CI: 1.76–2.04 for 3+ compared to 0), index hospitalization length of stay (OR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.50–1.69 for >7 compared to <4 days), ICU utilization (OR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.07–1.17), and greater comorbidities (OR: 1.75, 95% CI: 1.60–1.92 for 5+ compared to 0–1). Odds varied across hospital diagnostic categories and inpatient rehabilitation impairment groups. Patients with greater functional independence at rehabilitation admission had lower odds (self-care, OR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.53–0.62; bowel/bladder management, OR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.68–0.78; mobility, OR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.47–0.55; cognition, OR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.81–0.92 for highest versus lowest quartiles) of a potentially preventable within stay readmission.

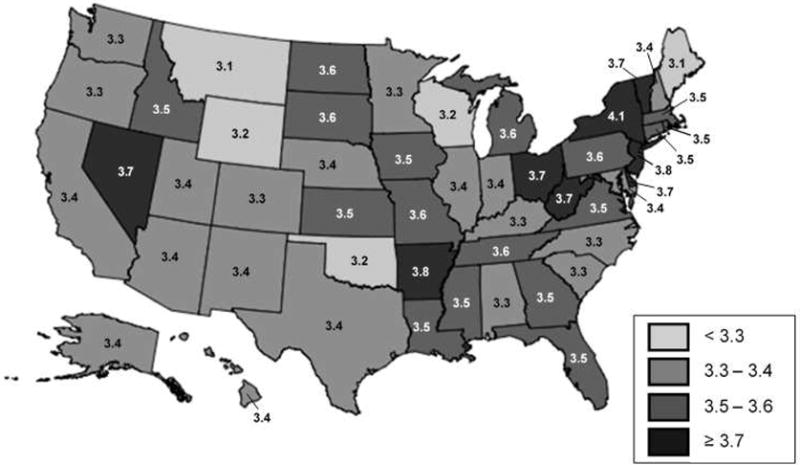

State-level variation in risk-standardized potentially preventable within stay readmission rates is presented in Figure 2. Across states, rates ranged from 3.1% (Montana and Maine) to 4.1% (New York).

Figure 2.

Risk-standardized state-level variation in rates of potentially preventable within stay readmissions.

Table 2 presents the five most common reasons for potentially preventable within stay readmissions by category: inadequate management of chronic conditions, inadequate management of infections, inadequate management of unplanned events, inadequate prophylaxis, and inadequate injury prevention. Of the identified potentially preventable readmissions, 36.8% were for diagnoses related to inadequate management of infections. Readmissions for diagnoses related to inadequate injury prevention were the least frequent (6.1%). Table 2 also presents an indicator for whether the listed diagnosis is included in the Prevention Quality Indictors developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.21 The readmissions related to inadequate prophylaxis and inadequate injury prevention were all for diagnoses unique to the proposed within stay measure.5

Table 2.

Five most common reasons for potentially preventable within stay readmissions during inpatient rehabilitation by category

| Inadequate Management of Infection (n=4396, 36.8%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-9 | Diagnosis | % | ACSCa |

| 038.9 | Unspecified septicemia | 43.2 | |

| 486 | Pneumonia organism unspecified | 18.4 | X |

| 599.0 | Urinary tract infection site not specified | 12.0 | X |

| 008.45 | Intestinal infection due to clostridium difficile | 5.2 | |

| 038.42 | Septicemia due to escherichia coli (E. coli) | 3.4 | |

| Inadequate Management of Other Unplanned Events (n=3161, 26.5%) | |||

| ICD-9 | Diagnosis | % | ACSC |

| 427.31 | Atrial Fibrillation | 28.3 | |

| 584.9 | Acute kidney failure, unspecified | 25.4 | X |

| 507.0 | Pneumonitis due to inhalation of food or vomitus | 24.2 | |

| 427.32 | Atrial flutter | 3.7 | |

| 276.1 | Hyposmolality and/or hyponatremia | 3.3 | |

| Inadequate Management of Chronic Conditions (n=2722, 22.8%) | |||

| ICD-9 | Diagnosis | % | ACSC |

| 428.33 | Acute on chronic diastolic heart failure | 17.9 | X |

| 428.23 | Acute on chronic systolic heart failure | 16.1 | X |

| 428.0 | Congestive heart failure | 11.1 | X |

| 491.21 | Obstructive Chronic Bronchitis with acute exacerbation | 9.7 | X |

| 428.43 | Acute on chronic combined systolic and diastolic heart failure | 5.5 | X |

| Inadequate Prophylaxis (n=938, 7.9%) | |||

| ICD-9 | Diagnosis | % | ACSC |

| 415.19 | Other pulmonary embolism and infarction | 55.4 | |

| 453.41 | Acute venous embolism and thrombosis of deep vessels of proximal lower extremity | 13.9 | |

| 453.40 | Acute venous embolism and thrombosis of unspecified deep vessels of lower extremity | 7.7 | |

| 453.42 | Acute venous embolism and thrombosis of deep vessels of distal lower extremity | 7.6 | |

| 707.03 | Pressure ulcer, lower back | 7.5 | |

| Inadequate Injury Prevention (n=728, 6.1%) | |||

| ICD-9 | Diagnosis | % | ACSC |

| 852.21 | Subdural hemorrhage following injury without mention of open intracranial wound with no loss of consciousness | 15.5 | |

| 852.20 | Subdural hemorrhage following injury without open intracranial wound with state of consciousness unspecified | 13.5 | |

| 820.21 | Fracture of intertrochanteric section of femur closed | 10.4 | |

| 820.8 | Fracture of unspecified part of neck of femur closed | 10.0 | |

| 820.09 | Other transcervical fracture of femur closed | 4.7 | |

ACSC, diagnoses included on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s list of “ambulatory care sensitive conditions”. Available at: http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/modules/pqi_resources.aspx

Discussion

Improving quality of care while reducing costs is the focus of healthcare reform.2 An important aspect of quality of care is patient safety.11 Outcomes identified as “potentially preventable” represent logical targets for improving patient safety, and consequently quality of care. Accordingly, potentially preventable hospital readmissions occurring while a patient is under the care of an inpatient rehabilitation provider is a recently adopted quality metric.4 A better understanding of these readmissions is needed, as prior research has focused on post-discharge readmissions and those that are all-cause or unplanned.

Patient Characteristics

An important first step for improving care through prevention efforts is to identify who is at increased risk. We were interested in describing the patient characteristics associated with greater odds of potentially preventable within stay readmissions. Unsurprisingly, patients with clinical characteristics indicating poorer health, such as prior hospitalizations, multiple comorbidities, and ICU utilization had higher odds of a potentially preventable within stay readmission. The association between clinical characteristics and risk of readmission has also been observed in post-discharge readmissions.6,7 However, compared to those occurring after discharge,6,8,22 it appears that sociodemographic characteristics, such as dual eligibility and race/ethnicity,8,22 may not play as important a role in risk for within stay readmissions.

There is an ongoing debate on whether to include sociodemographic variables in risk-adjustment models used for quality reporting and reimbursement.23 The National Quality Forum has stated that “each performance measure must be assessed individually to determine the appropriateness of SDS [sociodemographic status] adjustment.”24, p.6 CMS is currently testing whether to adjust the within stay readmission measure for race/ethnicity and dual eligibility.5 In our cohort, dual eligibility was not associated with potentially preventable within stay readmissions. Regarding race/ethnicity, rates of potentially preventable readmissions during inpatient rehabilitation were similar across white (3.5%), black (3.6%), and Hispanic (3.5%) race/ethnicities. In adjusted analyses, only Hispanic ethnicity demonstrated a weak association with readmission.

Another patient characteristic in the risk-adjustment spotlight is functional status.9,25 Functional status is associated with health outcomes, including post-discharge hospital readmissions.7,8,26 This relationship appears to extend to a patient’s risk for rehospitalization during inpatient rehabilitation, as well.27,28 In our cohort, greater functional independence at admission to inpatient rehabilitation was associated with lower odds of a potentially preventable within stay readmission. This relationship was consistent across all four functional domains, self-care, bowel/bladder management, mobility, and cognition. If patients’ functional status varies across inpatient rehabilitation facilities, then functional status may need to be included in case-mix adjustment when evaluating provider performance on this metric.

Geographic Variation

Risk-standardized rates varied across states, indicating rates in some states are worse than would be expected and in some states better than would be expected, given the patient-mix in the state. This finding further supports that some potentially preventable within stay readmissions may be avoidable and represent targets for care improvement initiatives.

Reasons for Readmissions

A unique list of potentially preventable diagnoses was developed for the proposed metric.5 By reporting the frequencies of readmissions for these specific conditions, our descriptive analyses are a starting point for identifying areas where providers are performing well and areas that represent targets for improvement. The potentially preventable diagnoses represent inadequate management of chronic conditions, inadequate management of infections, inadequate management of unplanned events, inadequate prophylaxis, or inadequate injury prevention. It appears that inpatient rehabilitation providers are performing well in preventing injuries and providing prophylaxis.5

Over one-third of the identified potentially preventable readmissions were for inadequate management of infection, with the most frequent being septicemia, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections. Although we cannot determine onset timing or mechanism from claims data, these are all common types of healthcare-acquired infections.29 Perhaps among some cases, unresolved issues from the prior hospitalization contribute to the patient’s risk for a readmission during inpatient rehabilitation. This concern was raised by experts during development of the within stay readmission metric.9 Reducing rates of healthcare-acquired infections is part of a national effort to improve patient safety and quality of care.11,30 According to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, healthcare-acquired infections are a “significant source of complications across the continuum of care and can be transmitted between different healthcare facilities.”29 A priority for CMS is greater integration and care coordination across providers.2 Our findings suggest prevention of within stay readmissions may be an area for providers (i.e. hospitals and inpatient rehabilitation facilities) to work together to improve patient safety and quality of care.

In our sample approximately 23% of potentially preventable readmissions were for inadequate management of chronic conditions (e.g. heart failure). The common diagnoses in this category all overlapped with the list of Prevention Quality Indicators developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.21 The Prevention Quality Indicators can be used to identify hospital admissions for “ambulatory care sensitive conditions;” conditions that should not occur under appropriate outpatient care.21 As these conditions should not occur under outpatient care, they should certainly be “avoidable with sufficient medical monitoring and appropriate patient treatment” in an inpatient setting.5 p.5 Better management of chronic conditions may represent a target for inpatient rehabilitation care improvement.

Broader Implications

Care improvement efforts extend beyond inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Postacute care in general (i.e. inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities, long-term acute care hospitals, and home health agencies) is the focus of many current healthcare reform initiatives.12,31 The IMPACT Act mandates the development of cross-cutting measures that can be used to compare quality and performance across postacute settings.12 Potentially preventable hospital readmissions is one of the cross-cutting measures specified in the IMPACT Act.12 Using a national sample, we examined the patient characteristics associated with greater odds of a within stay readmission and the reasons patients experienced this undesirable and potentially preventable outcome. We found 3.5 percent of stays had a potentially preventable within stay readmission. While this percentage is low, it represents 11,945 patient stays, and approximately $164 million in Medicare readmission costs ($13,800 per readmission).32

Some hospital readmissions during postacute care will be unavoidable. A majority of patients receiving care in this setting are recovering from a hospitalization for an illness or injury and are more susceptible to adverse health outcomes.28,33 However, our findings provide insight into a subset of readmissions that may be potentially preventable. Prevention of any readmission is beneficial at the individual (e.g. avoidance of exposure to hospital-acquired infections)34 and societal (e.g. reduced healthcare expenditures)31 levels. Our descriptive analyses suggest patients with clinical risk factors may benefit from increased surveillance during postacute rehabilitative care. Perhaps the use of within facility consultants or specialists would provide a proactive approach for reducing rates of potentially preventable within stay readmissions. However, postacute care is just one stage in an episode of care for an illness or injury. In this era of shared accountability, providers across settings will need to work together to improve patient outcomes. Preventing avoidable within stay readmissions may be a target for improving patient safety and quality of care across the continuum.

Limitations

Our analyses are largely descriptive; however, this is an important first step for understanding the implications of the proposed quality metric. Our findings provide a baseline for future analyses of rates and reasons for potentially preventable within stay readmissions. Baseline data will be critical for monitoring improvement on the metric, as well as for unintended consequences. Unintended consequences are a concern with the implementation of any new performance metric. Measure developers have noted the need to monitor to ensure that public reporting of potentially preventable within stay readmissions does not impact access to inpatient rehabilitation for more medically complex patients.5 As observed in our sample, these patients have higher odds of within stay readmissions. Providers may be incentivized to admit less complex patients who are at lower risk for this undesirable outcome.

Another limitation is the use of administrative data to address the study objective. Information on the accuracy of data entry is not available and may vary across providers. Additionally, analyses are restricted to variables submitted to the CMS by participating institutions. Sociodemographic information is limited and our findings in this area should be interpreted accordingly. Finally, our findings are generalizable to Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with characteristics similar to our cohort. We restricted our cohort to patients with inpatient rehabilitation lengths of stay of 3 to 45 days. This may have biased our sample to a healthier population, as patients with short-stays or stays longer than 45 days may be sicker and/or more functionally impaired populations.

Conclusions

Adoption of the potentially preventable within stay readmission metric will require CMS to develop and implement rigorous methods to evaluate provider performance and patient outcomes. Our study provides information on the patient characteristics associated with increased odds of potentially preventable within stay readmissions during inpatient rehabilitation. Patients’ clinical characteristics appear to have stronger associations with this outcome than patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. The risk-standardized variation in rates across states indicates there is likely room for improvement. Our findings highlight the need for care coordination across providers. Better management of infection and chronic conditions may represent targets for improving patient safety and quality of care across the continuum. Future research should focus on care processes that reduce patients’ risk of these potentially preventable rehospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

Funding: This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (R01 HD069443) and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (5K12HD055929-09); and the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center Award P30-AG024832, which is funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Prior presentation: Preliminary results were presented at AcademyHealth’s Annual Research Meeting in Boston, MA, June 26–28, 2016.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Level of Evidence: Level III

Contributor Information

Addie Middleton, Division of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Texas Medical Branch, 301 University Blvd, Galveston, Texas. Phone: 409.747.1611, Fax: 409.747.1638.

James E. Graham, Division of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Texas Medical Branch, 301 University Blvd, Galveston, Texas. Phone: 409.747.1636, Fax: 409.747.1638.

Anne Deutsch, RTI International and Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, 345 East Superior Street, Chicago, Illinois. Phone: 312.238.1000, Fax: 312.238.1369.

Kenneth J. Ottenbacher, Division of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Texas Medical Branch, 301 University Blvd, Galveston, Texas. Phone: 409.747.1635, Fax: 409.747.1638.

References

- 1.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, PL 111–148. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-law/read-the-law/index.html. Accessed 6/16/2016.

- 2.Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals–HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):897–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Register: Medicare Program; Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System for Federal Fiscal Year 2016; Final Rule. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Register. Medicare Program; Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System for Federal Fiscal Year 2017; Final Rule. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-08-05/pdf/2016-18196.pdf. Accessed 11/18/2016. [PubMed]

- 5.RTI International and Abt Associates. Draft Measure Specifications: Potentially Preventable Hospital Readmission Measures for Post-Acute Care. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/Draft-Measure-Specifications-for-Potentially-Preventable-Hospital-Readmission-Measures-for-PAC-.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 6.Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams JM. Patient Characteristics and Differences in Hospital Readmission Rates. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1803–1812. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):559–565. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ottenbacher KJ, Karmarkar A, Graham JE, et al. Thirty-day hospital readmission following discharge from postacute rehabilitation in fee-for-service Medicare patients. JAMA. 2014;311(6):604–614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.RTI International and Abt Associates. Technical Expert Panel Summary Report: Development of Potentially Preventable Readmission Measures for Post-Acute Care. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Post-Acute-Care-Quality-Initiatives/Downloads/Potentially-Preventable-Readmissions-TEP-Summary-Report.pdf. Accessed 5/30/2016.

- 10.Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/109/plaws/publ41/PLAW-109publ41.pdf. Accessed 11/18/2016.

- 11.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014. Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/113/hr4994. Accessed 9/1/2016.

- 13.Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014. Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/113/hr4302/text. Accessed 9/1/2016.

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) Training Manual. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/IRFPAI.html. Accessed 6/16/2016.

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) File. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/IdentifiableDataFiles/MedicareProviderAnalysisandReviewFile.html. Accessed 05/17/2016.

- 16.ResDAC. Master Beneficiary Summary File. Available at: https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/mbsf. Accessed 5/17/2016.

- 17.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) 2015. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/CCSUsersGuide.pdf. Accessed 5/16/2016.

- 18.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2016 Mar; Available at: http://medpac.gov/documents/reports/march-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy.pdf?sfvrsn=2. Accessed 7/20/2016.

- 20.Granger CV, Deutsch A, Russell C, Black T, Ottenbacher KJ. Modifications of the FIM instrument under the inpatient rehabilitation facility prospective payment system. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(11):883–892. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318152058a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Prevention Quality Indicators Overview. Available at: http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/modules/pqi_resources.aspx. Accessed 6/16/2016.

- 22.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiscella K, Burstin HR, Nerenz DR. Quality measures and sociodemographic risk factors: to adjust or not to adjust. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2615–2616. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Quality Forum. Risk Adjustment for Socioeconomic Status or Other Sociodemographic Factors, Technical Report. 2014 Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2014/08/Risk_Adjustment_for_Socioeconomic_Status_or_Other_Sociodemographic_Factors.aspx. Accessed 5/30/2016.

- 25.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Atanelov L, Knox B, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):277–282. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoyer EH, Needham DM, Miller J, Deutschendorf A, Friedman M, Brotman DJ. Functional status impairment is associated with unplanned readmissions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(10):1951–1958. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramey L, Goldstein R, Zafonte R, Ryan C, Kazis L, Schneider J. Variation in 30-Day Readmission Rates Among Medically Complex Patients at Inpatient Rehabilitation Facilities and Contributing Factors. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthcare-Associated Infections. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/healthcare-associated-infections. Accessed 11/18/2016.

- 30.Department of Health and Human Services. AHRQ’s Healthcare-Associated Infections Program. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/hais/index.html. Accessed 11/18/2016.

- 31.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) Medicare post-acute care reforms. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/congressional-testimony/testimony-medicare-post-acute-care-reforms-(energy-and-commerce).pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed 10/05/2015.

- 32.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) All-Cause Readmissions by Payer and Age, 2009–2013. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb199-Readmissions-Payer-Age.pdf. Accessed 11/18/2016.

- 33.Goodwin JS, Howrey B, Zhang DD, Kuo YF. Risk of continued institutionalization after hospitalization in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(12):1321–1327. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajaram R, Chung JW, Kinnier CV, et al. Hospital Characteristics Associated With Penalties in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program. JAMA. 2015;314(4):375–383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]