Abstract

Purpose

To accelerate the quantitative ultrashort echo time imaging using a time-efficient three-dimensional multispoke Cones sequence with magnetization transfer (3D UTE-Cones-MT) and signal modeling.

Methods

A 3D UTE-Cones-MT acquisition scheme with multispoke per MT preparation and a modified rectangular pulse (RP) approximation was developed for two-pool MT modeling of macromolecular and water components including their relative fractions, relaxation times and exchange rates. Numerical simulation and cadaveric specimens, including human Achilles tendon and bovine cortical bone, were investigated using a clinical 3T scanner.

Results

Numerical simulation showed that the modified RP model provided accurate estimation of MT parameters when multispokes were acquired per MT preparation. For the experiment with the Achilles tendon and cortical bone samples, the macromolecular fractions were 20.4±2.0% and 59.4±5.3%, respectively.

Conclusions

The 3D multispoke UTE-Cones-MT sequence can be used for fast volumetric assessment of macromolecular and water components in short T2 tissues.

Keywords: ultrashort echo time, Cones, magnetization transfer, two-pool modeling, short T2 tissues

Introduction

Conventional clinical MRI sequences can only assess tissues with relatively long T2s. Many joint tissues or tissue components, such as the deep radial and calcified cartilage, menisci, ligaments, tendons and bone have short T2s and show little or no signal with clinical sequences. Ultrashort echo time (UTE) sequences, with echo times (TEs) less than 0.1 ms, have been increasingly used on clinical MR scanners to directly image collagen-rich short T2 tissues or tissue components (1, 2). However, these tissues contain not only water, but macromolecule components such as collagen and proteoglycans (PGs). These macromolecules have extremely fast signal decay and remain “invisible” with all conventional clinical sequences as well as UTE sequences (3, 4). Quantifying both water and macromolecule components in both short and long T2 tissues, rather than just focusing on water in the longer T2 components in one specific tissue (e.g., articular cartilage), is likely to improve the sensitivity of MRI for the early diagnosis of osteoarthritis (OA).

Magnetization transfer (MT) imaging has been used for indirect assessment of macromolecules in biological tissues (5). Conventional MT sequences employ off-resonance saturation pulses to selectively saturate the proton magnetization of immobile macromolecules and indirectly saturate the magnetization of water protons. The simplest approach is to measure magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) which provides a measure of the magnetization change before and after the MT pulse. Reduction of MTR has been shown to be associated with collagen degradation and PG depletion (6). However, the measured MTR depends on many factors such as the specific details of the pulse sequence (i.e., MT power and frequency offset) and hardware (7), and does not provide quantitative information on macromolecular and water components in tissues.

In comparison, MT modeling provides lots of quantitative information, such as the fractions, relaxation times and exchange rates of different proton pools, which can be more promising than MTR in clinical use (8–11). Furthermore, the MT modeling parameters are magic angle insensitive as demonstrated by our recent studies of Achilles tendon samples using a 2D UTE-MT sequence, where tendon T2* varied by more than 7-fold while fractions and exchange rates varied by less than 10% when the sample orientation was changed from 0º to 55º relative to the B0 field (12).

In the last two decades, many groups have been dedicated to developing quantitative MT techniques. Henkelman et al. introduced two-pool MT modeling and used non-Lorentzian lineshapes for the macromolecular pool with continuous wave (CW) irradiation (8). Chai et al. introduced on-resonance binomial pulse saturation of the macromolecules to estimate MT parameters (13). Pulsed MT sequences with much lower specific absorption ratio (SAR) compared with the CW sequence would be more appropriate for clinical use. Three of the most widely used models are based on the pulsed MT sequence, including those developed by Sled and Pike (9, 10), Yarnykh et al., (12) and Ramani et al. (11). Sled and Pike proposed a rectangular pulse (RP) approximation of the MT pulse for the continuous saturation of the macromolecular pool and an immediate saturation approximation at the center of the RP pulse on the water pool for both MT and excitation pulses. The Sled and Pike RP model provided reliable and accurate estimation of the exchange and relaxation properties of agar gel phantoms and human brains (9, 10). Yarnykh et al. proposed a similar RP approximation (14). However, the saturation effects of both the MT and excitation pulses on the water pool were not considered. Ramani et al. proposed a continuous wave power equivalent (CWPE) model which averaged the power of the short MT pulse to the entire TR period without consideration of the excitation pulse (11). Thus, compared with the Yarnykh and Ramani models, the Sled and Pike RP model was more comprehensive since both the MT and excitation pulses were considered in the modeling (15, 16).

However, conventional quantitative MT techniques are not applicable to short T2 tissues such as tendons and cortical bone. Furthermore, multiple series of MT datasets with different MT powers and frequency offsets need to be acquired for MT modeling. This can be very time consuming, especially when volumetric imaging is used. More recently, a 3D multispoke UTE-Cones sequence has been used to improve scan efficiency (17). An extension of the original Sled and Pike RP model, which accounts for multispoke acquisition may be most appropriate for modeling. In this study, we proposed a three-dimensional multispoke UTE Cones MT sequence (3D UTE-Cones-MT) and a modified RP model to accelerate quantitative MT imaging of the Achilles tendon and cortical bone using a clinical 3T whole-body scanner.

Theory

Two-pool MT modeling

The two-pool MT model divides the spins within a biological tissue into two pools: 1) a water pool composed of water protons and 2) a macromolecular pool that consists of macromolecular protons (8). Each pool has its own set of intrinsic relaxation times. Magnetization exchange between the pools is modeled by a first-order rate constant (R). Henkelman et al. were among the first to incorporate modified Bloch equations into the mathematical description of the MT phenomenon by utilization of non-Lorentzian lineshapes for the macromolecular pool, which is shown as follows (8–11):

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

| [4] |

where are the fully relaxed magnetization of water and macromolecular pools, respectively. are the x, y and z components of the magnetization of water and macromolecular pools, respectively. w1 is the angular frequency of precession induced by the off-resonance MT pulse. Δf is the frequency offset of the MT pulse in Hz. R1w, 1m are the longitudinal rate constants and T2w, 2m are the transverse relaxation times. RRFm is the rate of longitudinal magnetization loss of the macromolecular proton pool due to the direct saturation of the MT pulse, which is related to the absorption lineshape G(2πΔf) of the spins in the macromolecular pool. This is given by:

| [5] |

Since the protons in the macromolecular pool do not experience the motional narrowing which those in the free pool do, their spectrum cannot be characterized by a Lorentzian lineshape function. Gaussian and super-Lorentzian lineshapes have been reported to provide good representations for the macromolecular pool (8, 9). The Gaussian and super-Lorentzian lineshapes are expressed as GG(2πΔf) and GsL(2πΔf), respectively:

| [6] |

| [7] |

where θ is the angle between the B0 and the axis of molecular orientation.

Two-pool Model Parameter Estimation

Sled and Pike proposed a two-pool MT model for pulsed imaging to simplify Eqs. [1] – [7] (9, 10). Here we extend their model for multispoke pulsed imaging (i.e. one MT pulse preparation followed by multiple acquisitions) to reduce the data acquisition time (Figure 1). The effect of an MT pulse on the macromolecular pool is modeled as a rectangular pulse (RP) approximation whose width is equal to the full width at half maximum of the curve obtained by squaring the MT pulse throughout its duration. The rectangular pulse has equivalent average power to that of the original MT pulse. On the other hand, the effect of the MT pulse on the water pool is modeled as an instantaneous fractional saturation of the longitudinal magnetization. Such instantaneous saturation (S1w) is estimated by numerically solving Eqs. [1], [3] and [4] when R and R1w are set to 0. For the excitation pulses, the instantaneous saturation of water component is cosNsp(α), where α is the excitation flip angle and Nsp is the number of spokes or excitations after each MT pulse preparation. This implies that the saturation effects of all the excitation pulses occurred precisely at the middle of the RP pulse. The original Sled and Pike RP model is a specific case of the modified model with Nsp = 1.

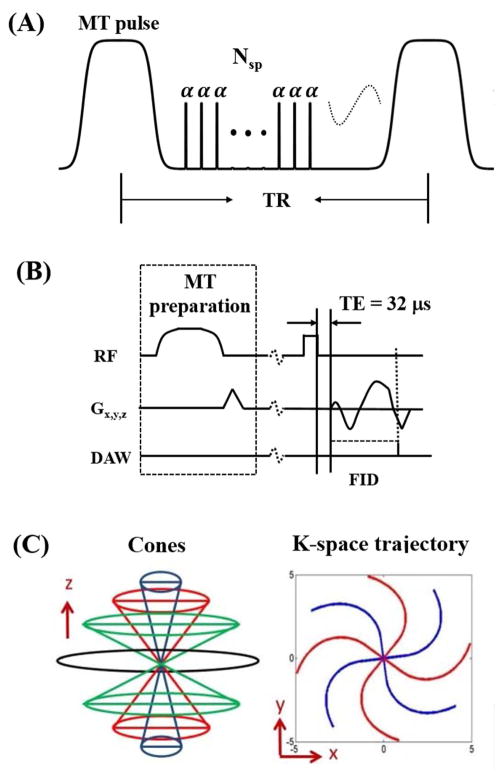

Figure 1.

The 3D multispoke UTE-Cones-MT sequence. A Fermi pulse was used for MT preparation followed by multiple spokes (Nsp) excitation (A). Each excitation employs a short rectangular pulse (duration = 26 μs) for signal excitation (B), followed by a 3D Cones trajectory (C) to allow time-efficient sampling with a minimal TE of 32 μs. Data acquisition window (DAW) starts at the beginning of the readout gradient.

Eq. [1] and [2] can be written in matrix form:

| [8] |

with and . A and B are the matrices corresponding to the coefficients in Eq. [1] and [2]. Here, only the longitudinal components are considered for computation and the transverse components are assumed to be negligible due to relaxation and spoiling (9).

Thus, instantaneous saturation of water pool, caused by both MT and excitation pulses, is simply described by multiplying Mz by the saturation matrix S:

| [9] |

After instantaneous saturation, the longitudinal magnetization becomes (assuming starting time t0):

| [10] |

The longitudinal magnetization after a period t1 is given by the matrix form solution of Eqs. [8] for either continuous wave (CW) or free precession (FP):

| [11] |

| [12] |

With

According to the RP approximation, during the time interval (i.e. one TR) between adjacent MT pulses, Mz successively undergoes instantaneous saturation, CW irradiation for a period τRP/2, FP for a period (TR-τRP) and CW for another τRP/2. Within a steady state, the equality is generated:

| [13] |

Mz is obtained by solving this equation in matrix form. Finally the observed signal SI(w1, Δf) is given as follows:

| [14] |

The more explicit formula derivation can be found in Appendix section. There are in total seven parameters (i.e. , R1w, R1m, , f, T2w, T2m) in the final expression. f is the macromolecular proton fraction defined as . As in previous work, R1m is fixed to 1 s−1 without affecting fitting results of other parameters (8). In addition, if R1obs(= 1/T1) is known, R1w can be obtained from other parameters (8–12):

| [15] |

The final number of independent parameters is therefore reduced to five, which can be estimated by fitting Eq. [13] using five or more measurements with different combinations of w1 and Δf.

Methods

Pulse Sequence

Figure 1 shows the 3D UTE-Cones-MT sequence implemented on a 3T Signa TwinSpeed scanner (GE Healthcare Technologies, Milwaukee, WI). The 3D multispoke UTE-Cones sequence (Figure 1A) employs Nsp short radio frequency (RF) rectangular pulses (duration = 26 μs) for signal excitation (Figure 1B), followed by 3D spiral trajectories with conical view ordering (Figure 1C) (17). The 3D UTE-Cones sequence allows for anisotropic resolution (e.g., high in-plane resolution and thicker slices) for much improved signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and reduced scan time relative to isotropic imaging. The MT preparation pulse was a Fermi pulse of 8ms duration (spectral bandwidth = 0.8kHz), maximal B1 of 24μT and 1740° maximal saturation flip angle, which provided an improved spectral profile compared with a rectangular pulse and higher efficiency (i.e. larger duty cycle) compared with Gaussian pulse (18). The 3D Cones images acquired with a series of MT pulse powers and off-resonance frequencies were used for two-pool MT modeling.

Since MT modeling requires repeated data acquisition with a series of MT powers and frequency offsets, the associated long scan time is a big challenge. To reduce total scan time, several spiral spokes (Nsp) can be acquired after each MT preparation pulse (total scan time being reduced by a factor of Nsp) (Figure 1A). This time efficiency greatly benefits clinical applications. The accuracy of this approach was evaluated via simulation (details below).

Numerical Simulations

We used the following MT parameters to compare our modified RP model with both the original Sled and Pike RP model and conventional CWPE model (11) with Bloch simulations from Eqs. [1]–[4]. The following parameters were used in the simulation: , R1w = 1.4 s−1, R1m = 1 s−1, , f = 0.2, T2w = 6 ms, T2m = 10.4 μs. Both Gaussian and Super-Lorentzian lineshapes for the macromolecular pool were tested. The sequence parameters were as follows: TR = 100 ms, Flip angle = 7°, MT powers = 500° and 1500°, 30 MT frequency offsets from 2KHz to 50KHz, and Nsp from 1 to 11. A Fermi pulse (duration = 8 ms, bandwidth = 160 Hz) was used for MT saturation. The duration between MT and the first excitation pulse was 5 ms. The duration between two adjacent excitation pulses was also 5 ms.

In Vitro Sample Study

Three human Achilles tendon specimens and three mature bovine cortical bone samples were used for evaluation of the 3D UTE-Cones-MT modeling with different excitation spokes. A home-built 1-inch solenoid coil was used for the Achilles tendon samples. A wrist coil (BC-10, Medspira, Minneapolis, MN) was used for cortical bone samples. The Cones-MT imaging protocol included: TR = 100 ms, TE = 32 μs, flip angle = 7°, FOV = 10×10×5 cm3 for cortical bone (5 mm slice thickness) and 8×8×2 cm3 for tendon (2 mm slice thickness), acquisition matrix = 128×128×10; Nsp from 1 to 11 to test the modified RP model, the duration of each spoke is 4.8 ms and readout bandwidth is 125 KHz; three MT powers (300°, 700° and 1100°) and five MT frequency offsets (2, 5, 10, 20 and 50 kHz), with a total of 15 different MT datasets. The total scan time was 59.5, 19.8, 12, 8.5, 6.8 and 5.5 min corresponding to Nsp = 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 11, respectively. T1 was measured using a 3D UTE-Cones acquisition with the same spatial resolution and a series of TRs (6, 15, 30, 50, 80 ms) with a fixed flip angle of 25° in a total scan time of 7.2 min.

Data Analysis

The analysis algorithm was written in Matlab (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) and was executed offline on the DICOM images obtained by the 3D UTE-Cones-MT protocols described above. Two-pool UTE-Cones-MT modeling and parameter mapping were performed on the tendon and bone samples. Mean and standard deviation of macromolecular proton fraction, relaxation time, exchange rates and water longitudinal relaxation were calculated.

Results

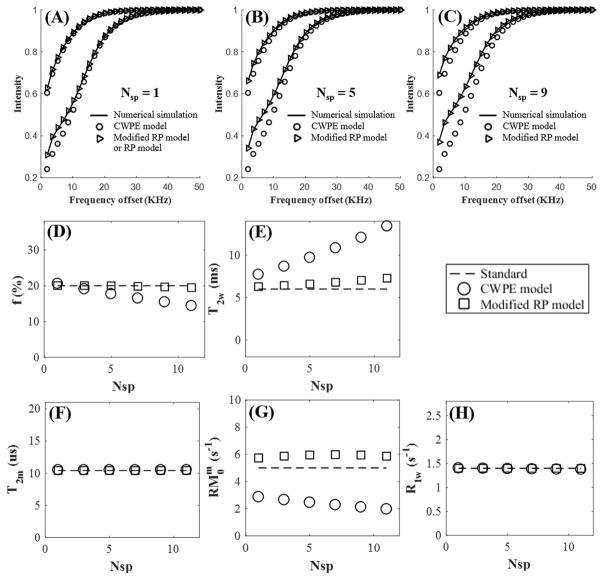

Figure 2 shows simulations of the two-pool MT model with a Super-Lorentzian lineshape, and a series of Nsp ranging from 1 to 11. The MT parameters were obtained from both RP and CWPE models by fitting the numerical simulated data. The new, modified RP model outperformed the CWPE model especially when more spokes were acquired per MT preparation. For a representative Nsp of 9, the CWPE model underestimated macromolecule fraction by more than 25% and by 60%, and overestimated T2w by more than 50%. In comparison the modified RP model can accurately estimate all these parameters, with less than 3% error for f, T2m and R1w. Slightly increased errors were observed for T2w and , but still less than 10% for a Nsp of 9. Very similar results were observed for the Gaussian lineshape, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Simulation on two-pool modeling of MT data acquired with two MT powers (500° and 1500°) and a series of frequency offsets ranging from 2 to 50 kHz for a Nsp of 1 (A), 5 (B), and 9 (C) using a Super-Lorentzian lineshape. The modified RP model fits much better than the CWPE model. MT parameters including f (D), T2w (E), T2m (F), RM0w (G) and R1w (H) are plotted against Nsp ranging from 1 to 11. MT parameters derived from the modified RP model show little variability with Nsp, while those from the CWPE model show significant variation with Nsp.

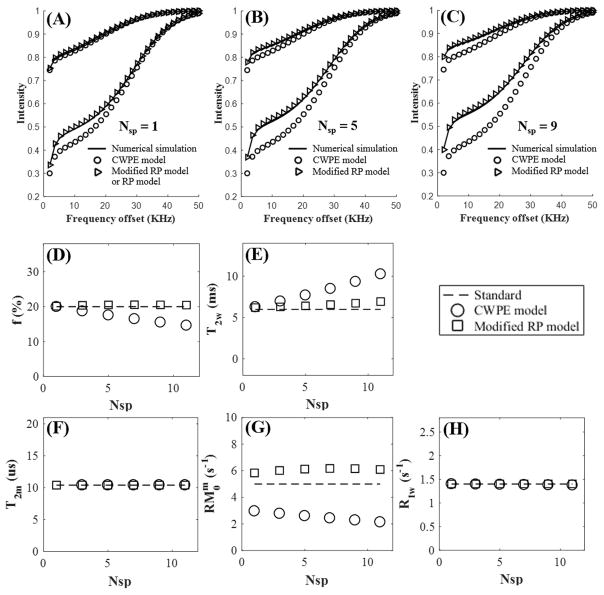

Figure 3.

Simulation on two-pool modeling of MT data acquired with two MT powers (500° and 1500°) and a series of frequency offsets ranging from 2 to 50 kHz for a Nsp of 1 (A), 5 (B), and 9 (C) using a Gaussian lineshape. The modified RP model fits much better than the CWPE model. MT parameters including f (D), T2w (E), T2m (F), RM0w (G) and R1w (H) are plotted against Nsp ranging from 1 to 11. MT parameters derived from the modified RP model show little variability with Nsp, while those from the CWPE model show significant variation with Nsp.

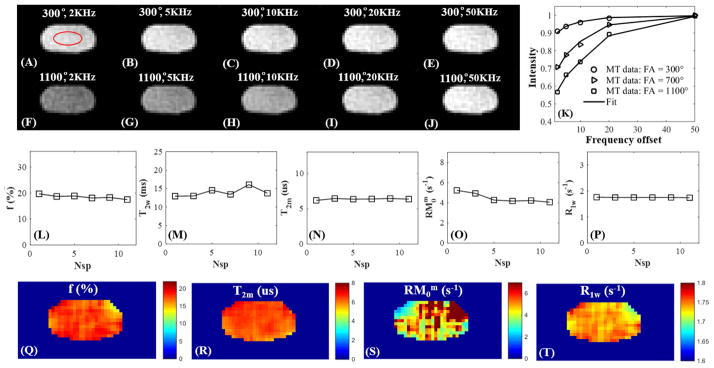

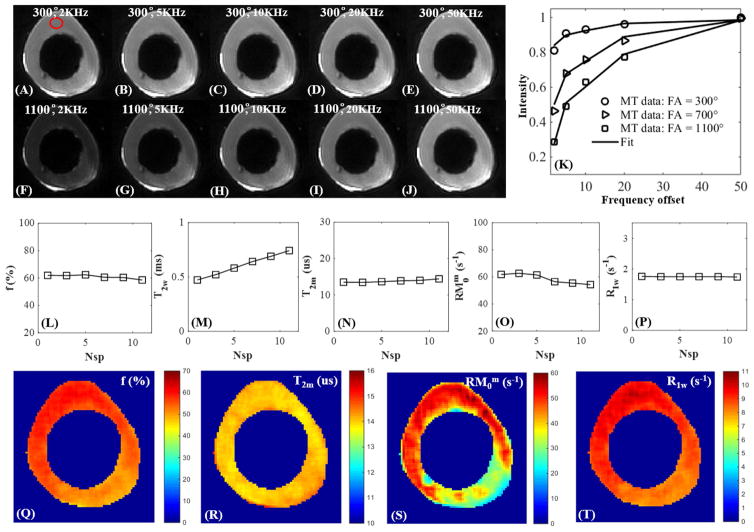

Figure 4 shows selected 3D UTE-Cones-MT images of a human Achilles tendon sample with two different MT powers (300º and 1100º) and five off-resonance frequencies (2, 5, 10, 20, 50 kHz). The clinically MR “invisible” Achilles tendon showed high signal on all Cones-MT images, allowing accurate two-pool MT modeling as shown in Figure 4K. A Super-Lorentzian lineshape was used for MT modeling. The MT parameters were relatively constant with different Nsp, further demonstrating the robustness of our new, modified RP model. The high quality UTE-Cones-MT images also allowed for mapping of two-pool MT parameters. RM0m showed increased variation suggesting that this parameter was subject to greater uncertainty. The MT modeling results (Nsp = 9) of the three Achilles tendon samples were as follows: f = 20.4±2.0%, T2m = 7.1±0.9 μs, and R1w = 1.7±0.1 s−1 with T1 = 639.7±49.9 ms. The results were similar to previous reported results especially for the macromolecular fractions (12, 19).

Figure 4.

Selected 3D Cones-MT images of a cadaveric human Achilles tendon sample acquired with an MT power of 300º and frequency offsets of 2 kHz (A), 5 kHz (B), 10 kHz (C), 20 kHz (D), 50 kHz (E), as well as an MT power of 1100º and five frequency offsets of 2 kHz (F), 5 kHz (G), 10 kHz (H), 20 kHz (I), 50 kHz (J) with Nsp = 9. Excellent two-pool fitting was achieved with the modified RP model (K). MT parameters including f (L), T2w (M), T2m (N), RM0w (O), R1w (P) are displayed as a function of Nsp. Selected mapping of f (Q), T2m (R), RM0m (S) and R1w (T) are also displayed. RM0m showed increased variation likely due to the greater uncertainty in estimating this parameter using the modified RP model.

Figure 5 shows selected 3D UTE-Cones-MT images of a cortical bone sample with two different MT powers (300º and 1100º) and five off-resonance frequencies (2, 5, 10, 20, 50 kHz). Cortical bone was depicted with high signal and spatial resolution on all UTE-Cones-MT images. The collagen in cortical bone is more solid-like in comparison to typical soft tissues such as tendon, therefore we employed the Gaussian lineshape in cortical bone for two-pool MT modeling. The MT parameters for bovine cortical bone were relatively constant with different Nsp, except for one parameter, T2w, which showed increased error with increase of Nsp (~40% overestimation for a Nsp of 9). The lower half of this bovine cortical bone sample showed increased signal intensity, which was in consistent with the reduced collagen proton fraction, and R1w. The MT modeling results (Nsp = 9) of the three cortical bones samples were as follows: f = 59.4±5.3%, T2m = 13.9±0.6 μs, and R1w = 9.9±0.6 s−1 with T1 = 237.7±16.7 ms.

Figure 5.

Selected 3D Cones-MT images of a cadaveric bovine cortical bone sample acquired with an MT power of 300º and five frequency offsets of 2 kHz (A), 5 kHz (B), 10 kHz (C), 20 kHz (D), 50 kHz (E), as well as an MT power of 1100º and five frequency offsets of 2 kHz (F), 5 kHz (G), 10 kHz (H), 20 kHz (I), 50 kHz (J) with Nsp = 9. Excellent two-pool fitting was achieved with the modified RP model (K). The MT parameters including f (L), T2w (M), T2m (N), RM0w (O), R1w (P) are displayed as a function of Nsp. Selected mapping of f (Q), T2m (R), RM0m (S) and R1w (T) are also displayed. The lower half of this bone sample showed greater variation in Cones image signal intensity and MT parameters which may need further investigation.

Discussion

MT modeling requires data acquisitions with several saturation pulse powers and frequency offsets. It may lead to excessively long scan time, making it difficult for clinical translation. Typical 3D UTE-Cones-MT imaging is even more time-consuming because of the high MT power (e.g., >1000º) which requires a relatively long TR to reduce SAR and a large number of volumetric encoding steps. Here we employed a fast multispoke acquisition scheme for 3D UTE-Cones-MT imaging and modified the RP model to fit the multispoke pulsed MT sequence. More than 59.5 minutes would be needed for the acquisition of 15 MT datasets if only one spoke was acquired per MT preparation. With the introduction of the multispoke approach (e.g., 9) per MT preparation, the total scan time for UTE-Cones-MT modeling can be reduced to less than 6.8 minutes which is clinically feasible.

To reduce errors associated with this multispoke approach, the modified RP model was proposed, which performed much better than the widely used CWPE model (11). The modified RP model results in nearly constant macromolecular fraction f, T2m, R1w and RM0m, although T2w showed greater errors with increasing Nsp. The 3D multispoke UTE-Cones-MT sequence together with the modified two-pool RP modeling largely preserved accuracy in estimating macromolecular and water fractions, relaxation times and exchange rates. Further, the proposed model might be more broadly applicable in that it may be applied to other segmented gradient echo sequences (such as FLASH), in addition to the UTE-Cones sequence.

Our study was largely consistent with the results from Sled and Pike (9, 10), who investigated quantitative interpretation of MT in spoiled gradient echo MRI sequences, which is the class to which the 3D UTE-Cones sequence belongs. In their simulation study, they noted that there is little benefit in choosing more than two MT powers for MT modeling (9). This suggests that we can further reduce scan time by using only two MT powers. Higher MT powers can saturate macromolecular protons more effectively, allowing more accurate MT modeling. However, proper consideration should be given to the MT powers that are used because higher MT power will generate higher SAR, which can be problematic, especially for in vivo studies. In this study, we focused on the MT effect in short T2 tissues such as cortical bone and the Achilles tendons which are “invisible” with conventional clinical MRI sequences. The Fermi-shaped pulse with high duty cycle used in our study is more efficient than Gaussian shaped pulses in saturating signal from short T2 tissues, facilitating MT modeling of water and macromolecular components in those tissues (18). Besides, the Fermi shaped RF pulse is more similar to rectangular pulse than Gaussian shaped pulses. Thus, Fermi pulse is more preferred for the RP model. The macromolecular components have a broad lineshape with a T2 around a few microseconds. Thus, a wide range of off-resonance frequencies and MT powers can generate a broad range of signal saturation. For MT modeling, the acquired data with a wide range of saturation including high saturation to non-saturation conditions are needed for accurate model fitting since there are a total of five fitting parameters. The choice of lineshape for macromolecular pool is also consistent with the literature (8–11). A Super-Lorentzian lineshape was used for the Achilles tendon, while a Gaussian lineshape was used for cortical bone which has a much shorter T2 (8, 20).

In this paper, we focused on MT modeling of short T2 tissues. However, MTR could also be calculated. For an example of Achilles tendon, the MTR values with a MT power of 1100º are as follows: 0.43 (2KHz offset), 0.33 (5KHz offset), 0.28 (10KHz offset), 0.12 (20KHz offset). The MTR values reported by Springer’s group are 0.32 (2KHz offset) and 0.24 (5KHz offset), where are lower than the values in our study because of a much lower MT power of 220º and a smaller TR of 11 ms (21). Additional experiments with similar sequence parameters are needed for more systematic comparison with past MT modeling and MTR results (21, 22).

Although T2* imaging has shown some promise in previous studies, it is highly sensitive to the magic angle effect (12, 23–25). The most significant advantage of the UTE MT modeling is the magic angle insensitivity, as demonstrated in Ref. 12. When the tissue fibers are oriented near 55º relative to the B0 field, their values may be increased by more than 100%. The MT modeling parameters other than T2* of water protons (such as macromolecular fraction and exchange rates) vary less than 10% between different angular orientations.

There are several limitations of this study. First, the total data acquisition time is still relatively long especially with higher image resolution and more coverage. Scan time may be further reduced by using advanced parallel imaging and compressed sensing reconstruction (26). Second, both B1 and B0 inhomogeneity can cause quantitative errors in MT modeling. Numerical simulation shows that 6% error in B1 or 1.3 kHz off-resonance will lead to 10% error in macromolecular fraction. MT modeling is more sensitive to B1 errors and less sensitive to B0 errors. In addition, cones readout are sensitive to the center frequency offset (i.e. B0 inhomogeneity), which will cause off-resonance artifacts. The artifacts will also lead inaccuracy of MT quantification. Thus, B1 and B0 correction should be helpful for more accurate MT quantification. In future studies, we will utilize a combination of the UTE-Cones sequence and the actual flip angle imaging (AFI) technique to map B1 inhomogeneity, allowing more accurate measurement of T1 and MT parameters (27). B0 inhomogeneity will be measured with a dual-echo UTE-Cones sequences. Third, the sensitivity of the MT parameters to early tissue degeneration was not investigated. Our next step is to apply the 3D UTE-Cones-MT technique to cadaveric knee joint specimens and correlate the MT parameters to tissue degeneration with histological correlation. Fourth, clinical evaluation of the 3D UTE-Cones-MT technique on patients remains to be investigated.

The 3D UTE-Cones-MT sequence opens the door to systematic evaluation of short T2 tissues such as the deep radial and calcified cartilage, menisci, ligaments, tendons and cortical bone, including their macromolecular and water components. Importantly, these MT biomarkers are magic angle insensitive (12). We expect that this technique will provide considerable value for the early detection of diseases such as OA and for monitoring the effects of therapy.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated a reliable method (i.e. the combination of the 3D multispoke UTE-Cones-MT sequence and modified RP model) for fast volumetric quantification of macromolecular and water components in short T2 tissues. By using a multispoke acquisition after each MT pulse, our proposed method was more time efficient than the original RP model, and showed higher accuracy compared with the CWPE model. We expect that this technique will be useful for detecting changes in relevant diseases such as OA.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge grant support from GE Healthcare and NIH (1R01 AR062581 and 1R01 AR068987) and the VA Clinical Science R&D Service (1I01CX001388).

Appendix

According to the RP approximation, Mz successively undergoes instantaneous saturation (i.e. S), CW irradiation for a period of half RP duration τRP/2, FP for a period (TR-τRP) and CW for another half RP duration τRP/2 in a TR. The following is the magnetization precession in a TR (assuming t0 = 0 for simplification):

| [A1] |

| [A2] |

| [A3] |

| [A4] |

Within a steady state, the equality is generated:

| [A5] |

After solve Eq. A1–A5, the signal of Mz(TR) is shown as follows:

| [A6] |

Then the final signal equation is expressed as follows:

| [A7] |

Where Mz(TR)1 is the first matrix element (i.e. longitudinal relaxation of water component) of Mz(TR).

References

- 1.Robson MD, Gatehouse PD, Bydder M, Bydder GM. Magnetic resonance: an introduction to Ultrashort TE (UTE) imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:825–846. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du J, Bydder GM. Qualitative and quantitative ultrashort-TE MRI of cortical bone. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:489–506. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lattanzio PJ, Marshall KW, Damyanovich AZ, Peemoeller H. Macromolecule and water magnetization exchange modeling in articular cartilage. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:840–851. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200012)44:6<840::aid-mrm4>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma YJ, Chang EY, Bydder GM, Du J. Can ultrashort-TE (UTE) MRI sequences on a 3T clinical scanner detect signal directly from collagen protons: freeze–dry and D2O exchange studies of cortical bone and Achilles tendon specimens. NMR in Biomedicine. 2016;29:912–917. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolff SD, Balaban RS. Magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) and tissue water proton relaxation in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1989;10:135–144. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li W, Hong L, Hu L, Maqin RL. Magnetization transfer imaging provides a quantitative measure of chondrogenic differentiation and tissue development. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:1407–1415. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry I, Barker GJ, Barkhof F, Campi A, Dousset V, Franconi JM, Gass A, Schreiber W, Miller DH, Tofts PS. A multicenter measurement of magnetization transfer ratio in normal white matter. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:441–446. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199903)9:3<441::aid-jmri12>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henkelman RM, Huang X, Xiang Q, Stanisz GJ, Swanson SD, Bronskill MJ. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29:759–766. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sled JG, Pike GB. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer in spoiled gradient echo MRI sequences. J Magn Reson. 2000;145:24–36. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sled JG, Pike GB. Quantitative imaging of magnetization transfer exchange and relaxation properties in vivo using MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:923–931. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramani A, Dalton C, Miller DH, Tofts PS, Barker GJ. Precise estimate of fundamental in-vivo MT parameters in human brain in clinically feasible times. Magn Reson Imag. 2002;20:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma YJ, Shao H, Du J, Chang EY. Ultrashort Echo Time Magnetization Transfer (UTE-MT) Imaging and Modeling: Magic Angle Independent Biomarkers of Tissue Properties. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:1546–1552. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chai JW, Chen C, Chen JH, Lee SK, Yeung HN. Estimation of in vivo proton intrinsic and cross-relaxation rate in human brain. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:147–152. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yarnykh VL. Pulsed Z-spectroscopic imaging of cross-relaxation parameters in tissues for human MRI: theory and clinical applications. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:929–939. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Portnoy S, Stanisz GJ. Modeling pulsed magnetization transfer. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:144–155. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cercignani M, Barker GJ. A comparison between equations describing in vivo MT: the effects of noise and sequence parameters. J Magn Reson. 2008;191:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carl M, Bydder GM, Du J. UTE imaging with simultaneous water and fat signal suppression using a time-efficient multispoke inversion recovery pulse sequence. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76:577–582. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du J, Takahashi A, Bydder M, Chung CB, Bydder GM. Ultrashort TE imaging with off-resonance saturation contrast (UTE-OSC) Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:527–531. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodgson RJ, Evans R, Wright P, Grainger AJ, O’Connor PJ, Helliwell P, McGonagle D, Emery P, Robson MD. Quantitative magnetization transfer ultrashort echo time imaging of the Achilles tendon. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(5):1372–1376. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang EY, Du J, Bae WC, Chung CB. Qualitative and Quantitative Ultrashort Echo Time Imaging of Musculoskeletal Tissues. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2015;19(4):375–386. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grosse U, Syha R, Martirosian P, Wuerslin C, Horger M, Grözinger G, Schick F, Springer F. Ultrashort echo time MR imaging with off-resonance saturation for characterization of pathologically altered Achilles tendons at 3 T. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(1):184–192. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Syha R, Martirosian P, Ketelsen D, Grosse U, Claussen CD, Schick F, Springer F. Magnetization transfer in human Achilles tendon assessed by a 3D ultrashort echo time sequence: quantitative examinations in healthy volunteers at 3T. Rofo. 2011;183(11):1043–1050. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juras V, Apprich S, Szomolanyi P, Bieri O, Deligianni X, Trattnig S. Bi-exponential T2 analysis of healthy and diseased Achilles tendons: an in vivo preliminary magnetic resonance study and correlation with clinical score. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(10):2814–2822. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2897-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juras V, Zbyn S, Pressl C, Valkovic L, Szomolanyi P, Frollo I, Trattnig S. Regional variations of T2* in healthy and pathologic Achilles tendon in vivo at 7 Tesla: preliminary results. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(5):1607–1613. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grosse U, Syha R, Hein T, Gatidis S, Grözinger G, Schabel C, Martirosian P, Schick F, Springer F. Diagnostic value of T1 and T2* relaxation times and off-resonance saturation effects in the evaluation of Achilles tendinopathy by MRI at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41(4):964–973. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lustig M, Donoho D, Pauly JM. Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(6):1182–95. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yarnykh VL. Optimal radiofrequency and gradient spoiling for improved accuracy of T1 and B1 measurements using fast steadystate techniques. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:1610–1626. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]